Home » Articles posted by Benerson Little (Page 6)

Author Archives: Benerson Little

An Early Skull & Crossbones at Sea, and More

Invariably as one of my books is published, my continued research uncovers relevant information ranging from corrections to supplementary material. In the past I have posted this information in a pdf file, often quite lengthy, but for this book I intend to post on the book’s page (GAoP above) and also especially on this blog.

And for my first supplement, a painting by Jacob Gerritsz, mid-seventeenth century, of an allegorical ship representing the Holy Roman Catholic Church. The painting is intended as anti-Calvinist propaganda demonstrating that Calvinists and other “Reformers,” including Calvin himself firing a musket at the ship, cannot harm the Holy Church. One of the banners the ship flies is a skull and crossbones, the earliest I’ve seen to date. The flag is merely a symbol here, representing death, but could the painter have been aware of the flag flying for real somewhere?

“Das Schiff der Kirche” by Jacob Gerritsz, circa 1640 to 1649. Copyright DHM/Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht.

Probably not, for why would the Church depict a ship (one of decidedly Spanish design) representing the Church flying a pirate banner? This is hardly the message the Vatican would like to present as an argument against Calvinism. More likely would be Calvinism, in the Roman Catholic Church’s eye, flying the flag of piracy.

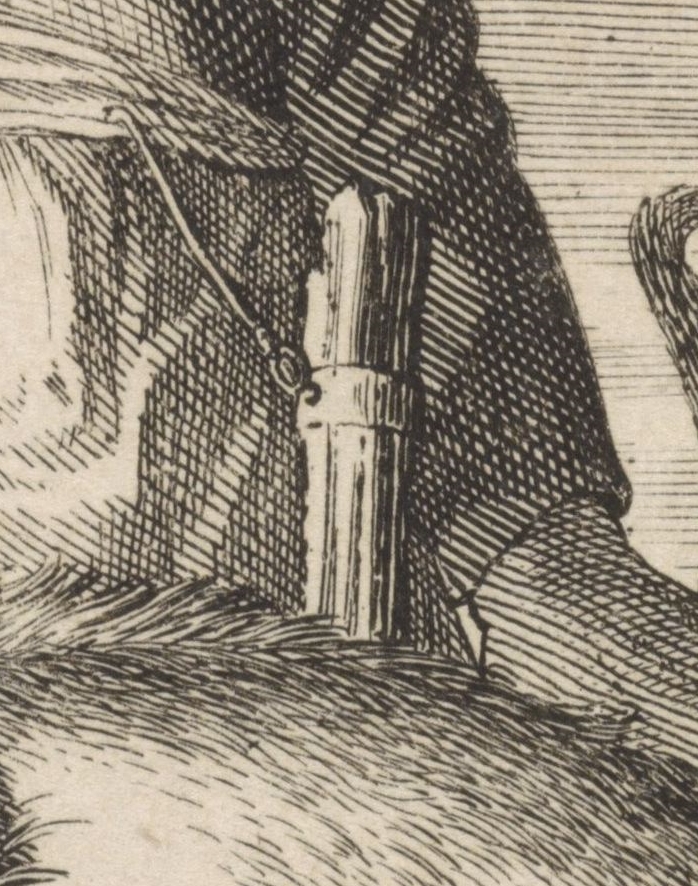

Detail from “Das Schiff der Kirche” by Jacob Gerritsz.

The fact is, although the skull and bones was used extensively as a mortuary symbol, and may have been flown at this time by some Barbary corsairs, it does not appear to have been regularly flown, with extensive attached symbolism, until the coming of the Anglo-American pirates in the early 18th century. Details, of course, are discussed in The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth About Pirate Myths.

The same black flag with skull and crossbones is similarly used in an allegorical poem of the early 18th century, prior to the American pirates who flew the skull and bones, to represent the banner of Charon, ferry-master of the Styx in Hades.

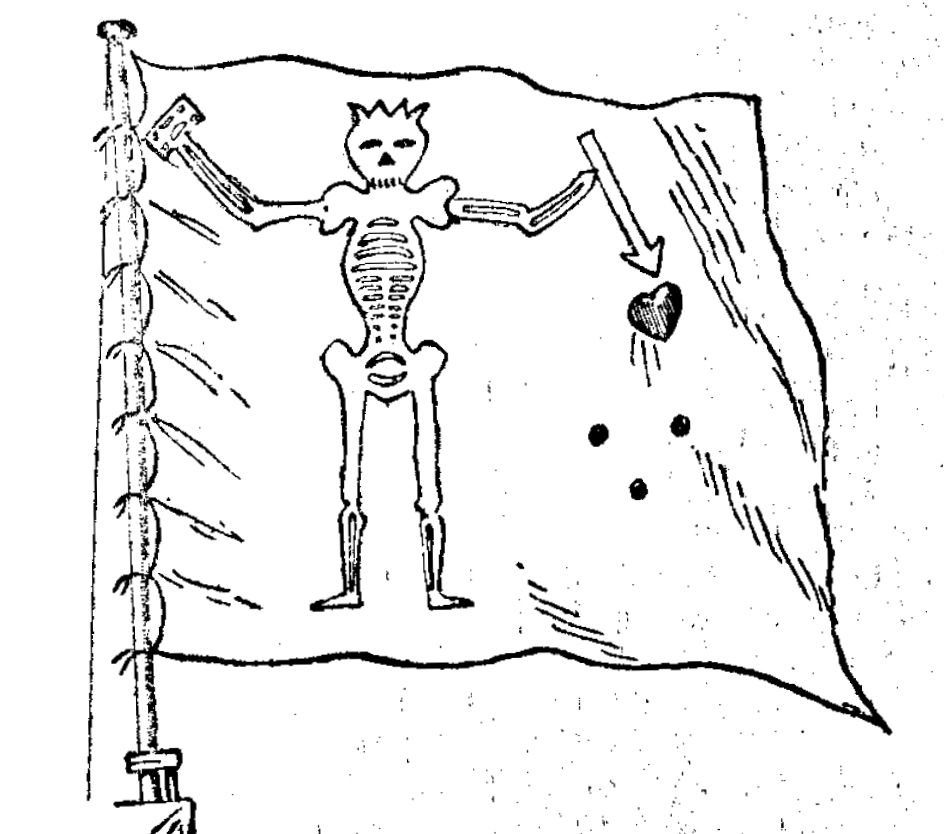

The death’s head in the painting above has a frightening three dimensional aspect, which would take a talented pirate to replicate with paint and brush. Most, we imagine–and we can only imagine, having no existing pirate flags from the Golden Age from 1655 to 1725, only written descriptions–would be simple fabric cutouts or simple painted images. However, in The Golden Age of Piracy I do discuss the flag of Jean Thomas Dulaien who sailed shortly after the period, for which we have a written description, as well as images of a purported drawing and of a purported woodblock made from the drawing. All are similar but none exactly matches the other. The original flag was reportedly destroyed on the order of Louis XIV.

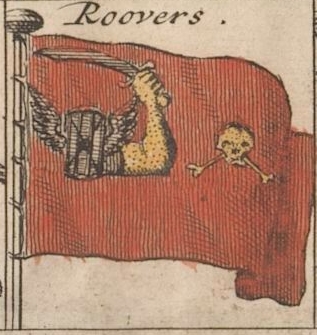

Except for a skull and bones flown on a red field–a flag of no quarter–by French flibustiers in 1688, and perhaps before and after, we have no evidence of their use among pirates and other sea rovers of European origin until the early 18th century, the first in 1700, and the rest circa 1715 and afterward. They may have been in use prior to this time by some of the Barbary corsairs. Details can be found in the first chapter of The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths.

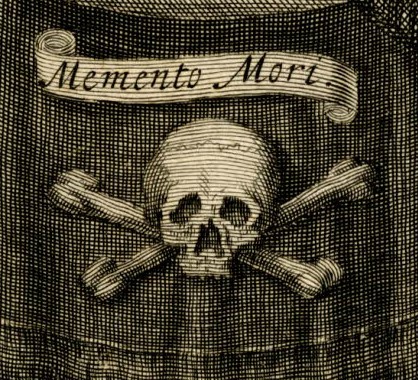

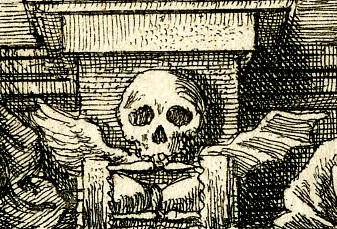

Banners with skull and bones have reportedly been around a long time, although depictions of them in art prior to the eighteenth century are difficult to find. Below is one by Hulderich Froelich of Basil, Switzerland, part of his 1588 Todtentanzes or “Dance of Death” series, one of which is Zwen Todentäntz, deren der eine zu Bern. Charles Hill, in his Episodes of Piracy in the Easter Seas, 1519 to 1851, published serially in the 1919 and 1920 editions of The Indian Antiquary, points this illustration out. Froelich’s “Dance of Death” along with others, is discussed in fair detail in here.

For the curious, what might the skull and crossbones, or skeleton, have looked like on real pirate flags of the early 18th century? We have only one likely authentic example of one, and it’s only a purported drawing of the flag of a French pirate, and of a woodcut believed to have been made from the drawing. More on them in a moment. The following are skulls and bones taken from a few late seventeenth century image showing various representations.

Detail from a portrait of Ernst Eberhard Friedrich, Count of Hohenlohe-Langenburg. Circa 1671. After Johann Georg Kreutzfelder, print made by Jacob von Sand. British Museum.

Detail from the Dance of Death series. After Abraham van Diepenbeeck (border), after Hans Holbein the Younger, print made by Wenceslaus Hollar. 1651. British Museum.

Detail from the Dance of Death series. After Abraham van Diepenbeeck (border), after Hans Holbein the Younger, print made by Wenceslaus Hollar. 1651. British Museum.

As for the one real “Golden Age” pirate flag we have an image of (there are no existing examples of real pirate flags from this era), it just barely makes it into the era, as at 1729 it’s late for the period that generally is regarded to end at 1725 or 1728. It’s also not the flag of a pirate of an Anglo-American pirate, but a French one, from France and returning to France. The pirate in question is Jean-Thomas Dulaien, whom I’ve discussed along with his flag in The Golden Age of Piracy. The first image below was reportedly created from the original flag, which was reportedly destroyed by order of Louis XIV; the second is of a woodblock or woodblock print made from the image.

The purported Dulaien original, copied from the actual flag. Clearly, if the image is accurate (there’s no reason to believe it is not), the skull, bones, and man with cutlass and hourglass was painted on. The original flag was, according to reports at the time, destroyed.

The purported woodcut image made from the original illustration. Clearly it is only a representation of the original image, and not an entirely accurate reflection.

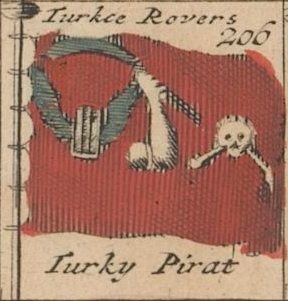

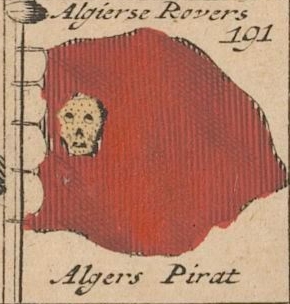

Likewise, since publication I’ve also identified earlier images of the red flags of the Islamic corsairs, one dating to 1711, the others probably 1707 to 1711. Clearly these sea-going flags were around prior to the Anglo-American pirates who used similar flags, as were others I’ve noted in the book itself.

Schouw-park aller Scheeps-vlaggen des geheelen Water-Waerelds, 1711. The flag is shown among Barbary and Turkish sea flags. This flag is popularly, and incorrectly, attributed to the pirate Christopher Moody. (Rijksmuseum.)

Ottoman corsair flag from Nieuwe Tafel van alle de Scheeps Vlaggen des Gehele Water-Waerelds op Nieus Vermeerdert en Verbeeterdt, probably dating 1707 to 1711, possibly slightly later, based on some of the English flags shown. The Rijksmuseum incorrectly dates it 1650 to 1700.

Algiers red banner with death’s head, from Nieuwe Tafel van alle de Scheeps Vlaggen des Gehele Water-Waerelds op Nieus Vermeerdert en Verbeeterdt, dated as immediately above.

And last, a note on the purported flag of Blackbeard. Historian Ed Fox has pointed out that, according to The Mariner’s Mirror (1912, vol. 2, no. 3) the horned Blackbeard flag first appears in The Book of Buried Treasure by R. D. Paine (Ralph Delahaye), 1911. The book was reprinted in 1981 by Arno Press. The drawing is fanciful but is based on a legitimate period description of a pirate flag. A later artist or publisher ascribed it, with minor modification emphasizing devil horns, to Blackbeard.

Copyright Benerson Little 2016-2018. Originally published December 19, 2016, last updated December 9, 2018.

The Authentic Eyewitness Image of the Real Buccaneer

The dashing image in the banner above–in which Peter Blood’s posed-for-the-camera attack has been parried by the equally posed Captain Levasseur, and Blood needs to recover quickly before he finds a blade in his eye or his belly–is taken from an original publicity still for Captain Blood, 1935, starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone. The film duel between Flynn and Rathbone, of clashing swords on California sand, is without doubt the most iconic of Hollywood sword fights, and although it has often been imitated, the results have almost never been quite as satisfactory. Certainly no other film “duel on the beach” is so evocative.

Therefore, in view of the foregoing, not to mention my long admiration for both the novel by Rafael Sabatini and its film version directed by Michael Curtiz, and as much for fun and nostalgia as for education, I’ll spend my first dozen or more blog posts working my way through authentic, literary, and film swordplay among pirates, with occasional associated digressions.

However, before we draw swords and explore the myth and reality of fencing with “sharps” among pirates and others, we’ll consider what the seafaring thieves of the 1680s Caribbean actually looked like, and how they were armed. Was this anything like Sabatini or Curtiz represented them? Was it anything like illustrators and Hollywood artists—Howard Pyle and Douglas Fairbanks, for example, whose works have come to define the image of the buccaneer—dressed them up and showed them off?

Fanciful illustration, “The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow,” by Howard Pyle, from “The Fate of a Treasure-Town” in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1906. Reprinted in Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

To begin, we require a few definitions. With a few exceptions, most of the Caribbean sea rovers from 1655, when England piratically seized Jamaica from Spain, to 1688, when Europe went to all out open war, existed in a gray area between legitimate privateering and outright piracy. At times these sea rovers had legitimate commissions, at times a mere “wink and a nod” from local authority, and at times no commissions at all, or forged ones, or falsely extended ones. In all cases these rovers eschewed the term pirate for two reasons: first, piracy was a hanging offense, and second, they considered themselves as something better than common pirates. After all, they not only attacked well-armed Spanish ships at sea, but they also, in military order, sacked Spanish towns.

A somewhat more accurate illustration of a buccaneer threatening a Spanish prisoner, from the frontispiece to Exquemelin’s Historie der Boecaniers, of Vrybuyters van America, 1700. (John Carter Brown Library.)

Their preferred terms were, among the English-associated rovers, privateer and buccaneer. The former proclaimed their legitimacy, the latter their unique place. The term buccaneer derives from boucanier, the term for the French cattle and swine hunter of Hispaniola, which derives from boucan, a Tupi word meaning grill or grate for cooking and smoking meat and fish. (Similarly, barbecue derives from the Spanish barbacoa, which derives from the Taino word for the grill or grate.) The French-associated rovers, on the other hand, used the term flibustier, which, as far as we can tell, originated with the Dutch vryjbuiter, which was anglicized via a pretty much direct translation as freebooter, which the French adopted as fribustier and flibustier, which was later anglicized as filibuster. Occasionally the French used the term aventurier, or adventurer, which accurately reflected the men drawn from all walks of life to the trade. (For eyewitness images of boucaniers, go here.)

From a number of eyewitness written descriptions we have a pretty good idea what these buccaneers and filibusters looked like, or at least enough of an idea to make some reasonable conjectures. Unfortunately, lacking archaeological evidence, we are likely to make some mistakes.We cannot even rely on period illustrations in first-hand accounts about buccaneers, for it is almost certain that the illustrators never saw their subjects. The only exception may be the illustrations of Henry Morgan, who is likely, given his fame, to have sat for a portrait in London while there after sacking Panama.

Worse, fiction, popular illustration, and film have corrupted our idea of what these gentlemen of semi-legitimate fortune may have looked like, as in the case of Howard Pyle’s romantic image above. Therefore, rather than provide several written descriptions first and speculate from them, we’ll cut to the chase and see with our own eyes exactly what Captain Peter Blood’s buccaneers and filibusters really would have looked like.

It turns out that in the archives of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) and the French Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer (ANOM), are a couple dozen charts of French Caribbean ports, primarily those of Saint-Domingue on Hispaniola, made during the 1680s by French engineers. In other words, these are charts rendered by eyewitnesses. And in the cartouches of a fair number are detailed eyewitness drawings of filibusters and boucaniers, as well as of the occasional common worker, probably an engagé (indentured servant), and the occasional slave.

I discovered these by accident a few years ago. I wasn’t the first to do so, but I was, as far as I know, the first to analyze some of them in detail and publish the results (Mariner’s Mirror, August 2012). Their significance had been almost entirely overlooked. For me, the discovery made me feel as if I had briefly traveled back in time—and left me disappointed I could not remain at least for a while.

And here’s why! In this first image, we see a pair of buccaneers or flibustiers at Petit Goave on Saint-Domingue, the western half of Hispaniola claimed by the French. By the 1680s Petit Goave had replaced Tortuga as the sea roving port on Saint-Domingue, and was populated by a large number of flibustiers of several nationalities, colors, and ethnicities.

A pair of flibustiers or buccaneers at Petit Goave, 1688, from a chart by P. Cornuau. (Courtesy of the Archives Nationale d’Outre-Mer.)

The buccaneer on the left is armed with long-barreled fusil boucanier, or “buccaneer gun” in English, the common weapon of the Caribbean sea rover. He wears a large cartouche box at his left front, and a cutlass at the side behind it. We can assume from his scabbard that his cutlass is, like his companion’s, made with a clip point, a common style during the era. His hat is small-brimmed, turned up on the left side, and appears to have a small plume. He wears a stylish cravat. His coat is fairly long, and short-sleeved with large cuffs. He may be wearing a sash over it. His stockings are conventional and worn over the knee as was the practice at the time, and his shoes are conventional with short tongues.

His swashbuckling companion is armed with a cutlass whose hilt, given its style, is probably of brass. He likewise wears a large cartouche box at the left front. His hat is broad-brimmed with a large plume, and is turned up at the front. He appears to wear a cravat. His jacket is shorter, with two rows of buttons, short sleeves with cuffs (or rolled up sleeves), and he has a sash tied around his waist, almost certainly with a belt over it to hold cartouche box and cutlass. He wears seaman’s breeches, possibly un-gathered, with stockings that appear to be worn over the knee. His shoes are conventional. It’s impossible to know if they are buckled or tied.

A buccaneer or flibustier at Île-à-Vache, 1686, from a chart by P. Cornuau. (Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

Next we have a couple of flibustiers or buccaneers drawn at Île-à-Vache, a common rendezvous off the southwest coast of Hispaniola. Our buccaneer on the right is armed with a fusil boucanier, as most were. The musket is correctly depicted at half-cock, and the deep notch at the neck is the sort later known as “female.” His large cartouche box is worn at the left front over a sash and certainly on a belt. His jacket is short, with large cuffs. His wide, probably open breeches are those of a seaman. His shoes common, his hat broad-brimmed and with a plume. He may have a mustache, and, notably, his hair is shoulder-length and loose. Many seamen–and buccaneers were a combination seaman and soldier–wore their hair tied back or in a queue so that it would not get in their faces or get drawn into a block. But at least among the buccaneers and flibustiers, this rule did not always apply.

Flibustier or buccaneer at Île-à-Vache, 1686, from a chart by P. Cornuau. (Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

At the left is another buccaneer and his fusil boucanier, again correctly at half-cock, along with his typical large cartouche box–commonly holding thirty-six cartridges–at the left front. He has a cutlass, although all that’s visible is the scabbard on his right side, making him left-handed. Again, the cutlass is clip-pointed. His hat is turned up at the right side, with a plume on the left, although it’s possible the hat is actually a boucanier’s cropped hat (see next blog post). Like the previous buccaneer, his jacket is short, but with smaller cuffs. His shirt has a bit of lace at the cuffs, and he wears a cravat. His stockings are secured at the knee, and his shoes common, apparently with short tongues.

In the image below, made by “Partenay” aboard the small French man-of-war Le Marin in 1688, we can compare illustrators for accuracy. It depicts two aventuriers, the one on the left possibly a boucanier, given the wild pig at his feet, although he may in fact be a flibustier (boucaniers often accompanied flibustiers, and some men went back and forth between the trades), and the one on the right probably a flibustier. Both men wear fairly broad-brimmed hats turned up at the front, and both wear what are probably wide seaman’s breeches, but similar garments–caleçons of linen or canvas, often open at the knee–were common to boucaniers, indentured servants, and others. Both men have loose shoulder length hair. The hunter or flibustier on the left wears a common shirt, large and loose, and appears to have a cravat or kerchief at the neck and tucked into the shirt. The fusil boucanier is of the “club butt” style which, at least in the eighteenth century, came to be the most common. Note the short clay pipe smoked by the flibustier on the right.

Boucanier and buccaneer, or two buccaneers, at the French sea rover haven of Petit Goave in 1687 or 1688, drawn by Partenay in 1688. (Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

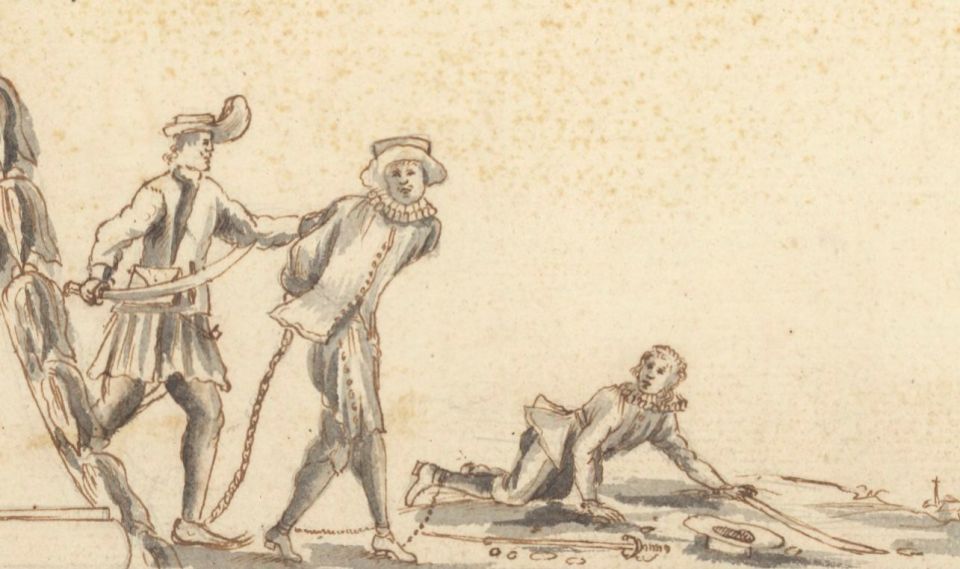

In the image below, again by Cornuau, we see a flibustier with two captured Spaniards in chains. He is armed with cutlass with a small shell or shells, and a strongly curved blade with a clip-point. His scabbard hangs from a sword belt common to the period, that is, with two straps, with loops at the end, hanging from the belt. His large, obviously thirty round, cartouche box is on his right side, perhaps an illustrator error, perhaps personal preference. He wears a short, perhaps crude jacket, probably of osnabrig canvas or sackcloth. He also wears wide seaman’s breeches, as many of his associated do. His head covering is a boucanier cropped hat, and his footwear is a pair of crude boucanier shoes made of raw pigskin cut from pig hocks. This footwear seems common among flibustiers, and may be what Father Avila meant when referring to pigskin shoes among the flibustiers. (See also The Authentic Image of the Boucanier for more details on these shoes.)

Flibustier with captured Spaniards in chains. From the French chart “Carte particulière de la rivière de la Plata” by Paul Cornuau, probably 1684 based on a nearly identical chart he drew of the River Plate dated 1684.

These buccaneers or filibusters are probably dressed as they commonly were, particularly ashore in their own ports. The arms they bear in the images above are also largely what they would use during attacks at sea, even during boarding actions against ships whose crews had retreated to closed quarters: even here the musket had its uses. It was less useful, of course, in hand-to-hand action on open decks. Common arms used during attacks on ships were the musket to suppress enemy fire and pick him off, as well as to engage enemy loopholes in closed quarters; the cutlass and pistol for close combat; the boarding ax, often along with a hand-crow, for chopping into decks and bulkheads in order to breach closed quarters (and it from this purpose that the boarding ax gets its name); the cartridge box for reloading musket and pistol; and the grenade, fire-pot, or stink-pot for destroying men in the open on deck, and particularly for tossing into breaches made in closed quarters, in order to flush the enemy out or otherwise force him to surrender.

What we do not yet see are these sea rovers fully dressed and armed for an attack on a Spanish town–but Caruana, the creator of most of the charts that interest us, does not disappoint. He provides us with an iconic image of a buccaneer or flibustier fully equipped for an attack ashore! Beginning with his clothing, he wears a broad-brimmed hat. His hair is either short, or more likely, tied at the back. His jacket is moderately long, his belt narrow (as are all those in these images, not the wide Hollywood belts for these flibustiers), his breeches conventional, not of the sort commonly worn by seamen. He may or may not be wearing stockings: if his shoes are those worn by boucaniers (see next blog post), then he wears no stockings.

But it is his armament we are most interested in. He has a fusil boucanier over his shoulder, again at half cock. In his left hand is a paper cartridge which would hold both ball and powder, and sometimes seven or eight swan shot on top of a single ball, and power. The cartridge had been early adopted by boucaniers and flibustiers, and they learned early the lesson that conventional armies would learn after them: that the flintlock with cartridge was the most efficient weapon for campaigning, and, eventually, for conventional warfare.

At his waist is a cutlass, this one with an obvious brass hilt given its shape, and without a clip point as can be discerned by the shape of the scabbard and its chape. He has a cartouche box on his belt, again on the left front, and on his right front is a single pistol. Notably, its lock is against his body (this would help protect the lock), with the butt to his left for an easy draw. I’ve tested this way of carrying a pistol: it works well with small to medium pistols, although large pistols (12″ and longer barrels) are easier to carry putting the belt-hook on the inside, with the pistol hanging on the outside, although the pistol is less secure this way. With two pistols, one would be carried on the left side, the other left-front, assuming a right-handed shooter.

This setup is well-balanced: cutlass and cartouche box on one side, pistol (often a pair) on the other. At Veracruz flibustiers were noted as carrying two cartouche boxes: the second was probably worn at the back, and carried additional cartridges, most of which were almost certainly for use with the musket, the buccaneer’s primary weapon according to buccaneer and surgeon Alexandre Exquemelin. In our flibustier’s right front pocket is a small powder horn, almost certainly for re-priming the pan as necessary. Buccaneers primed from the cartridge as they loaded, but would require a horn to re-prime if, for example, the powder in the pan got damp.

Two more details deserve attention. First, above his belt is a thin cloth that serves as a mosquito netting. Such netting is described in at least three eyewitness sources. It was usually worn around the waist or over the shoulder like a bandoleer. Second, around his neck is a detail almost never seen: a musket tool used variously, depending on the tool, for clearing the vent, chipping a dull flint to get another shot or two before it must be changed out, tightening the cock, as well as other tasks associated with cleaning and maintaining a musket.

There exist substantial written evidence to support these images. Father Jean-Baptiste Labat has described the flamboyant dress of flibustiers, especially after pillaging a ship’s cargo (a scene that may well have inspired a similar scene in Frenchman’s Creek, 1944). The arms of the flibustiers–fusil boucanier, cartouche box, one or two pistols, a cutlass–are described several times by eyewitnesses. What we have not had is this eyewitness corroboration in the form of images.

We also have an eyewitness account by one of the victims of a buccaneer attack, in this case the brutal rape and pillaging of Veracruz in 1683, of which I will speak more of in a later blog. The account adds details we have hitherto lacked. According to Fray Juan de Avila, the flibustiers wore “sailcloth jackets, shoes of cowhide but more wore those of pigskin [possibly cheaper shoes, or even those the boucaniers commonly wore, or both], and others wore jackets of blue sackcloth [possibly dyed with indigo from Saint-Domingue]” and were armed with “a cutlass, a large (or long) flintlock musket [clearly a buccaneer gun], two pistols, and hanging from a waist belt two cartridge boxes with paper cartridges inside…”

In sum, these buccaneers or flibustiers are much as we imagined them: picturesque and picaresque, a combination of Hollywood and reality long before Hollywood ever existed. But note what we do not see: no peg legs (extremely rare in reality, for they make buccaneering difficult), no eye patches except due to injury (absolute myth created by literature and illustration and unfortunately further spread by Mythbusters, &c.), few obvious tattoos (some men and women, not just seamen, had a few but not to the degree we like to believe), no insignia of skull and bones (although some may have worn mortuary rings with such symbolism, as did people from all walks of life), no earrings (although foppish pirates may have worn them on occasion, and Dutch seamen, along with many Dutch in general, did wear them), and no parrots–although some pirates did in fact keep parrots, although more often than not probably as plunder. Also, please note that none wear boots. Fishermen wore boots at times, seamen in arctic waters did too, but otherwise, seamen, including sea rovers, did not. Worse, the boots we see pirates in film, television, and illustration wear are riding boots–and one doesn’t ride horses aboard ship.

I will get to discussing swordplay soon enough, but the next blog post will describe in similar detail the dress and arms of the boucanier, of the cow and pig hunters who often accompanied flibustiers on their attacks at sea and ashore.

Bibliography

Avila, Juan de. “Pillage de la ville de Veracruz par les pirates le 18 mai 1683 (Expedition de Lorencillo).” Amoxcalli manuscript no. 266, http://amoxcalli.org.mx/paleografia.php?id=266.

Captain Blood. Warner Brothers Pictures, 1935.

Cornuau, Paul. “Carte particulière de la rivière de la Plata.” Probably 1684. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan des passes et du bourg du levé et dessigné par ordre de Mr. De Cussy, Gouverneur pour le Roy de l’isle de la Tortue et coste St. Domingue.” 1685. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan du Cap et de son entrée,” 1684. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan Ignographique du Fon et de l’Isle à Vache,” 1686. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan ignographique du Fon et de l’Isle à Vache,” 1686 (second chart bearing this title). Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan du Petit Goave et de l’Acul, avec le Figuré du Fort du Petit Goave tel qu’il a été Reformé, avec Deux Autres Plans de ce Même Fort.” Circa 1688. Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer.

Exquemelin, A. O. [Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin]. De Americaensche zee-roovers. Amsterdam: Jan ten Hoorn, 1678.

——. Bucaniers of America. London: William Crooke, 1684.

—— [Alexander Olivier O’Exquemelin]. Histoire des avanturiers qui se sont signalez dans les Indes. 2 vols. Paris: Jacques Le Febure,1688.

——. Historie der Boecaniers, of Vrybuyters van America. Amsterdam: Nicolaas ten Hoorn, 1700.

——. The History of the Bucaniers. London: T. Malthus, 1684.

——. Piratas de la America, y luz à la defensa de las costas de Indias Occidentales. Translated from the Dutch by Alonso de Buena-Maison. Cologne: Lorenza Struickman, 1681.

Labat, Jean Baptiste. Nouveau Voyage aux Isles d’Amerique. 6 vols. Paris: Guillaume Cavelier, 1722.

Little, Benerson. The Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish Main, 1674–1688. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2007.

——. “Did Pirates Wear Eye Patches?” On the Under the Black Flag website at <http://undertheblackflag.com/?p=2904> or at <http://www.benersonlittle.com/bio.htm>.

——. “Eyewitness Images of Buccaneers and Their Vessels.” The Mariner’s Mirror, vol. 98, no. 3 (2012), 312–326.

——. The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths. New York: Skyhorse Publishing ,2016.

——. “El Mito Pirata.” Desperta Ferro, no. 17 (August 2015), 52-55.

——. The Sea Rover’s Practice: Pirate Tactics and Techniques 1630–1730. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005.

——. “Las Tácticas de los Piratas del Caribe.” Desperta Ferro, no. 17 (August 2015), 27-32.

Partenay. “Ainsy se fait voir le Petit Gouave au Sud-est et nord oist éloignée . . . ,” 1688. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Pyle, Howard. The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow. In “The Fate of a Treasure-Town” by Howard Pyle. Harper’s Monthly Magazine (December 1905).

Sabatini, Rafael. Captain Blood, His Odyssey. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1922.