Howard Pyle’s Famous “An Attack on a Spanish Galleon” — and Some Real Galleons Too!

Perhaps the most famous of Howard Pyle’s many piratical paintings and drawings, and certainly the most evocative, “Attack on a Spanish Galleon” has inspired many homages (and plagiarisms) in book illustrations, cinema, and advertising — not mention dreams of Spanish treasure in the minds of both armchair and real sea-going adventurers!

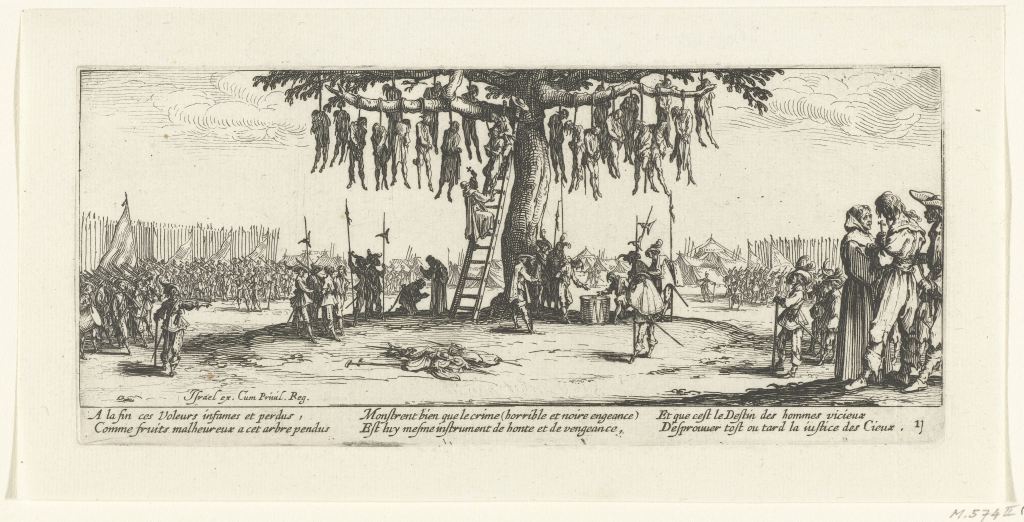

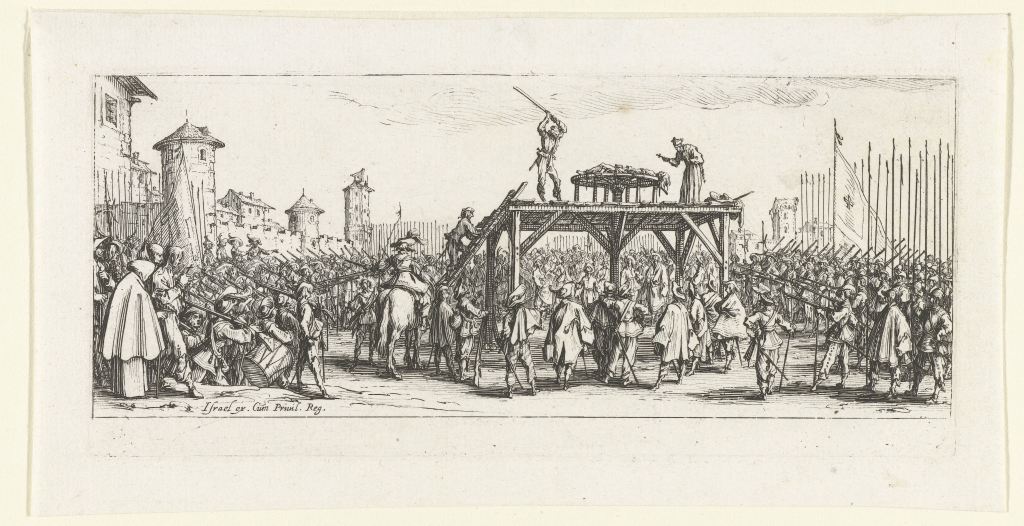

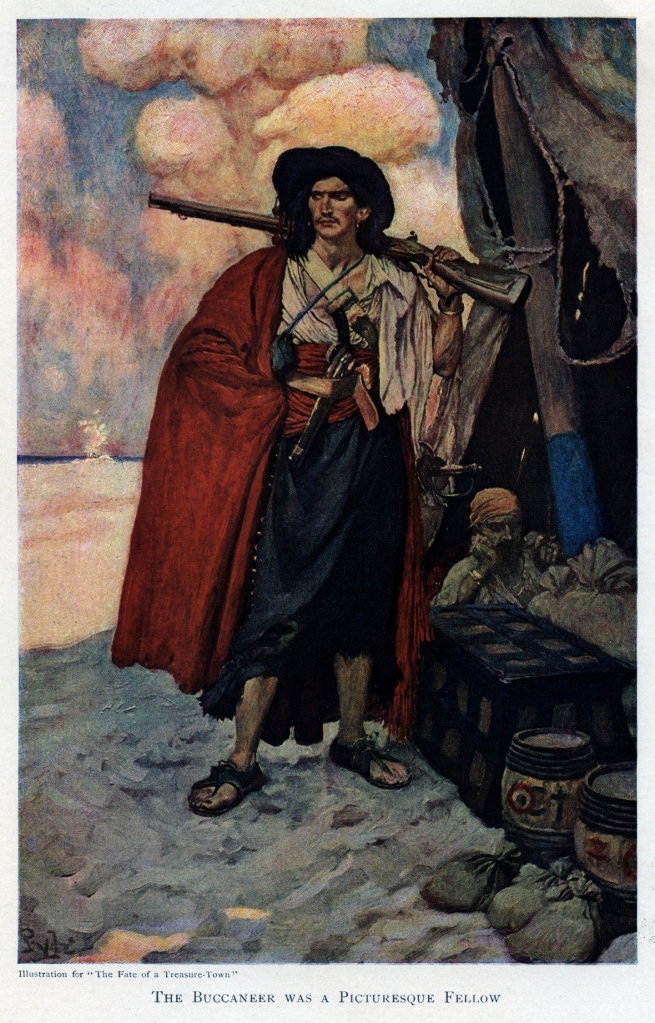

The illustration accompanies several other of Pyle’s most famous buccaneer paintings in “The Fate of a Treasure Town,” an article written by Howard Pyle about the 1697 sack of Cartagena de Indias and published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1905. The article includes some of Pyle’s most famous buccaneer paintings, including “The Buccaneer was a Picturesque Fellow,” “Extorting Tribute from the Citizens” (used as the cover of The Buccaneer’s Realm, for what it’s worth), and “So the Treasure Was Divided.” Of the most famous paintings of his buccaneer, as opposed to pirate, series, only “Which Shall be Captain?” for “The Buccaneers,” a book of poetry, by Don C. Seitz in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, January 1911, and “How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas,” in Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899, are missing.

Charles D. Abbott in Howard Pyle: A Chronicle (Harper & Brothers, 1925) considers these four paintings as the culmination of Pyle’s paintings in “the pirate vein,” although he argues that the painting of “Captain Keitt, standing on the slanting deck of ship with a high sea running behind and a burning galleon in the distance, is perhaps the best of all of Howard Pyle’s pirate pictures.” Even so, he notes that “The one called ‘Attack on a Galleon,’ with its marvelous golds and greens, is a splendid achievement in design.”

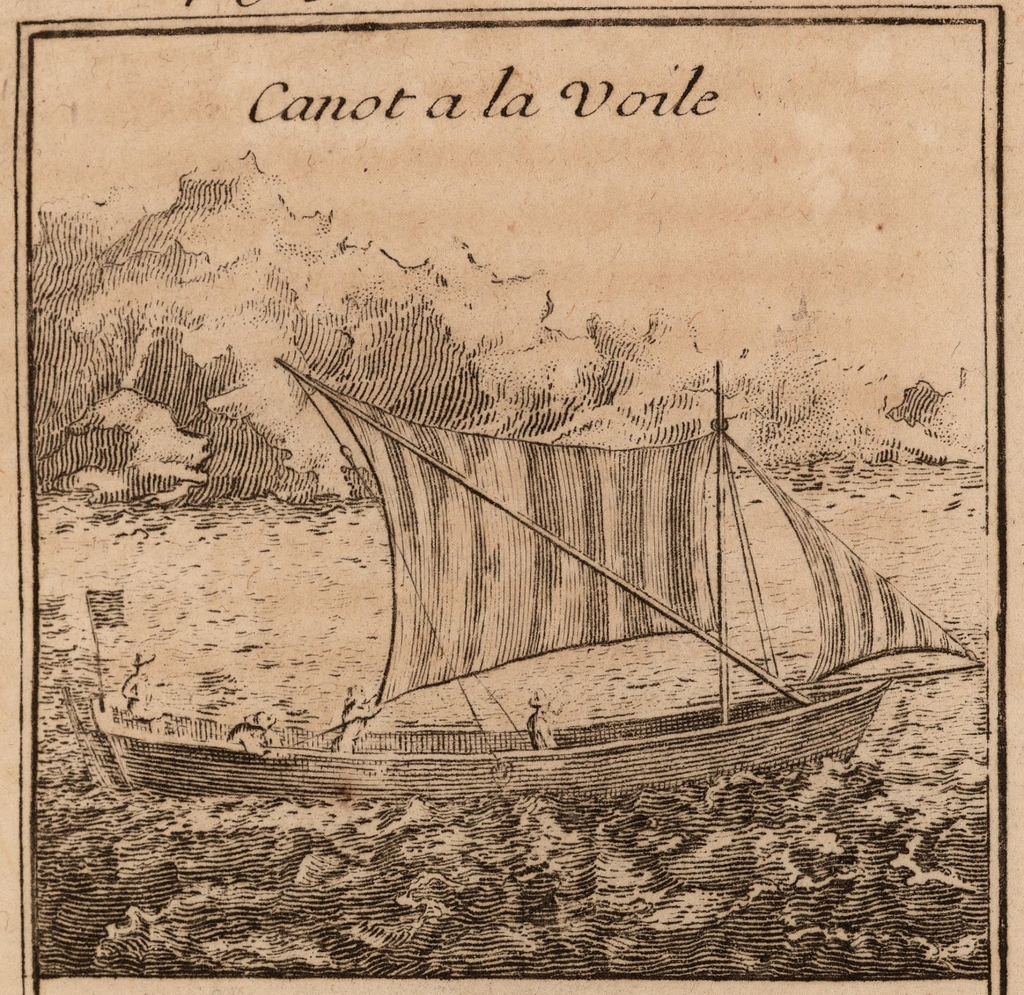

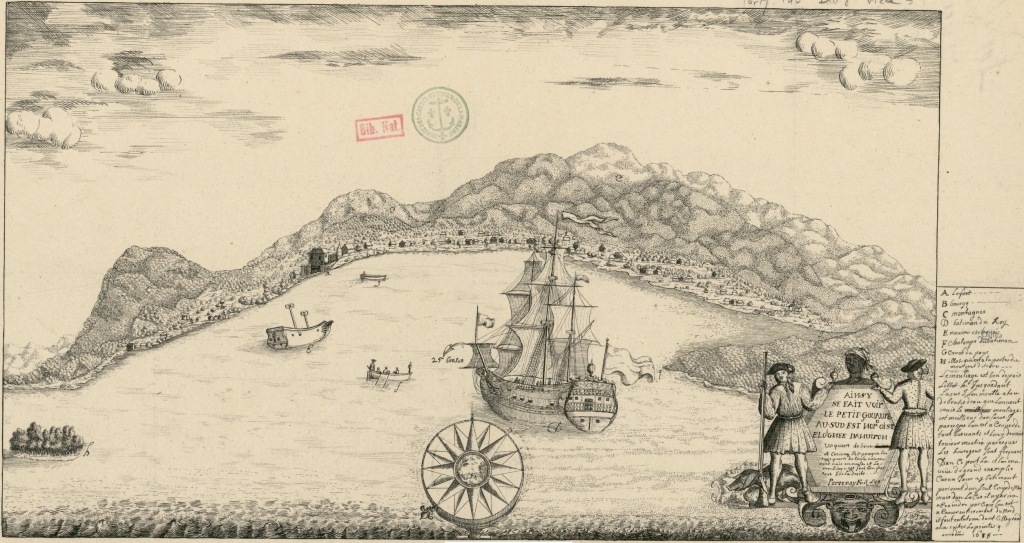

Although the attack on a galleon scene in illustration, fiction, and film in general was surely inspired by buccaneer-surgeon-author Alexandre Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America (first ed. 1678), Pyle’s was likely factually-inspired by Exquemelin’s possibly apocryphal tale of Pierre Le Grand who captured a Spanish treasure ship by boarding at night. The small buccaneer crew had only one craft and boarded by stealth, catching the Spanish captain and crew off-guard — they had disregarded the distant buccaneer craft as of no threat to a great galleon.

The story may be apocryphal but it has the ring of truth. We know that historically other buccaneers captured Spanish vessels by boarding from small boats, canoes, and periagers (piraguas, pirogues), that sea rovers in general have successfully made similar attacks over the millennia, and that modern naval special operations forces use the tactic as well. (For more information on the tactics of Golden Age buccaneers, pirates, privateers, and naval commerce raiders, see The Sea Rover’s Practice.)

In the painting, one buccaneer boat is already alongside, its boarders streaming up the side and into the waist, and another, gaff-rigged, a dugout canoe perhaps, is captivatingly astern, surely preparing to board as well. The smoke billowing from the deck indicates a fierce fight on deck — muskets and pistols, and probably the upper deck great guns and swivel guns as well, are in action — or possibly even that the ship may be afire, although in the latter circumstance it is unlikely that buccaneers would board, for a fire aboard ship was feared more than any other hazard of the sea.

At the stern, probably on the poop deck, one can sea a Spaniard in a broad Spanish hat, often referred to as a “two-hand hat” (or perhaps it is one of the buccaneers instead?) and aft of him, perhaps on the poop-royal (also known as the topgallant poop, Sp. chopeta/chopa/imperial, Fr. dunette sur dunette/carrosse), a pair of hands in submission and supplication.

A question that continues to perplex me is what time of day does this attack take place? Is that a golden full moon just up over the horizon at sunrise, given its red-orange color? Or is it a sunset, suggesting the setting and settling of a Spanish treasure voyage?

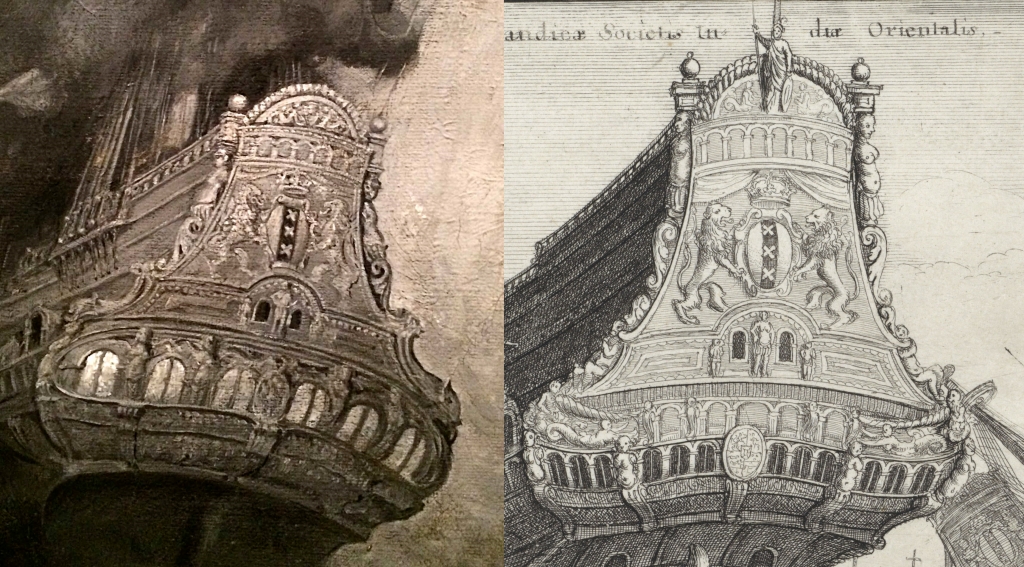

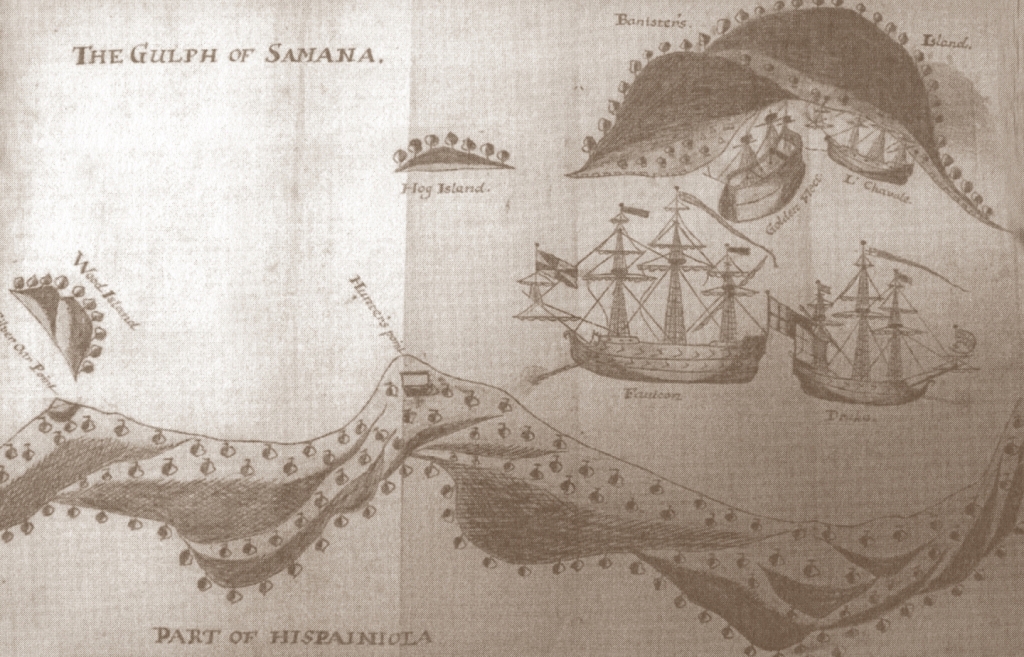

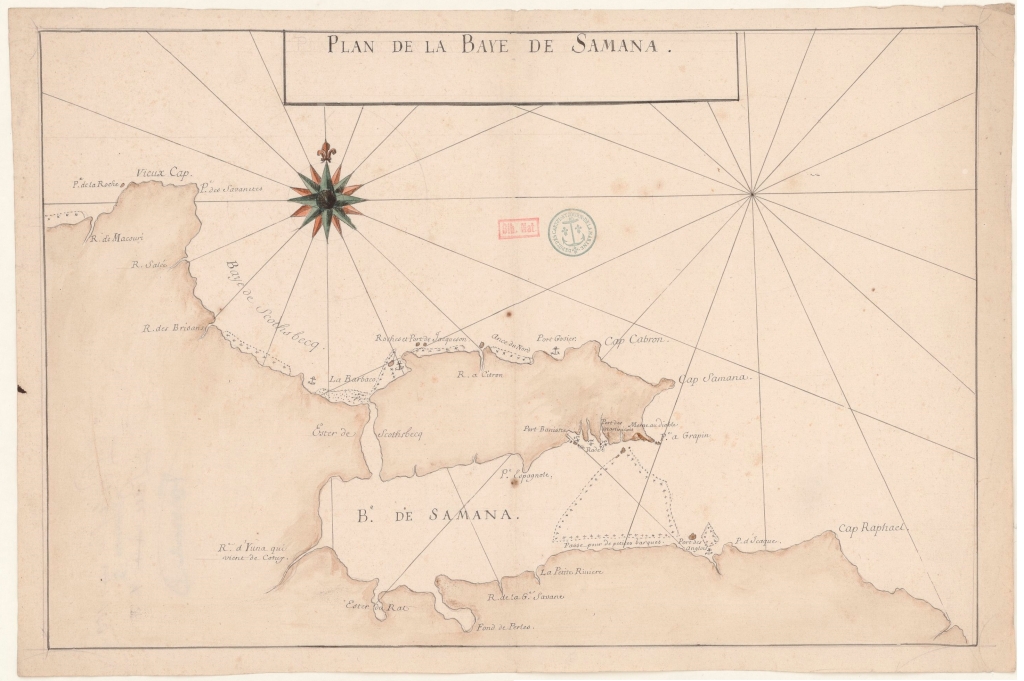

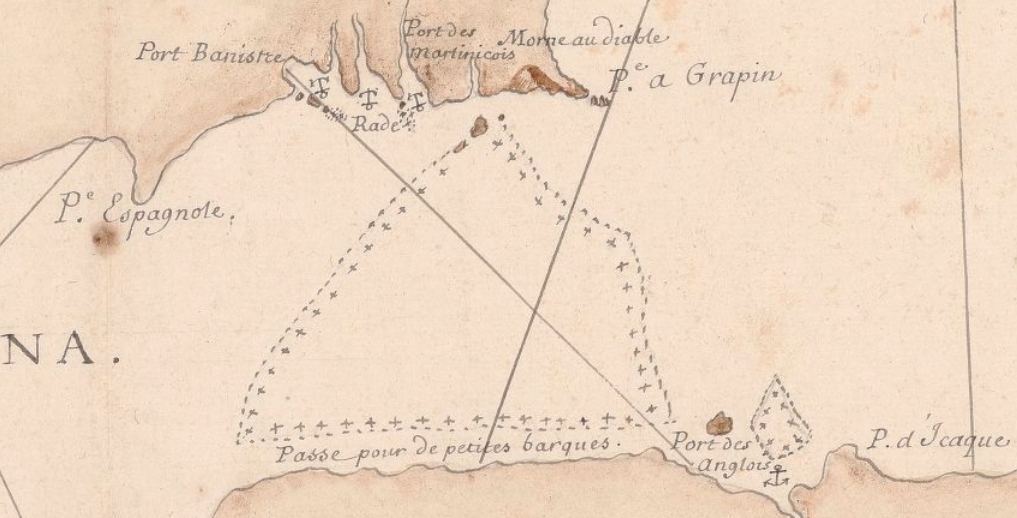

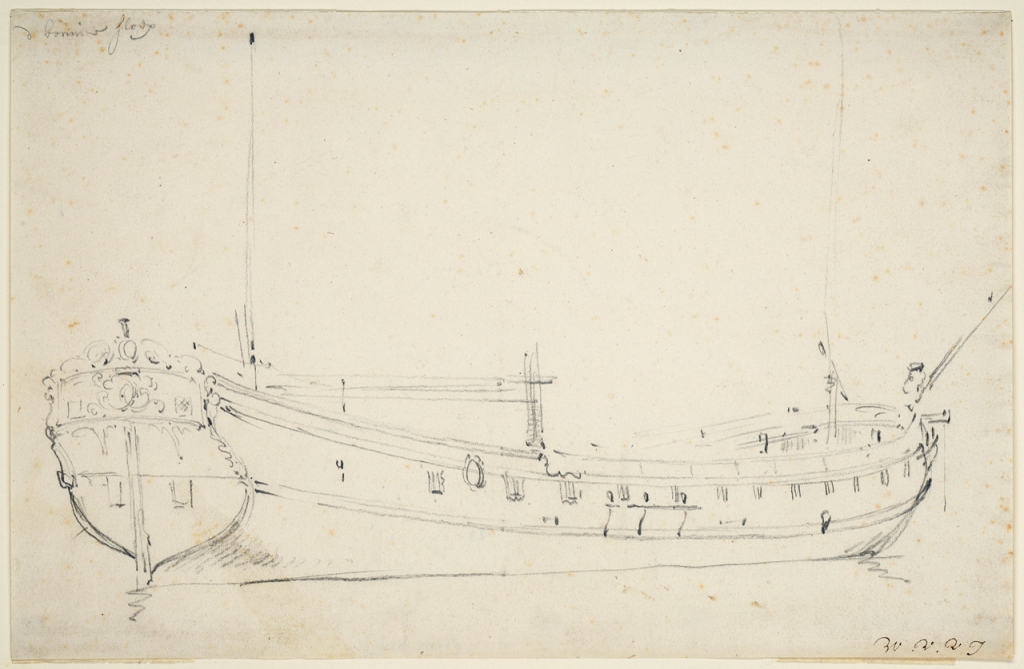

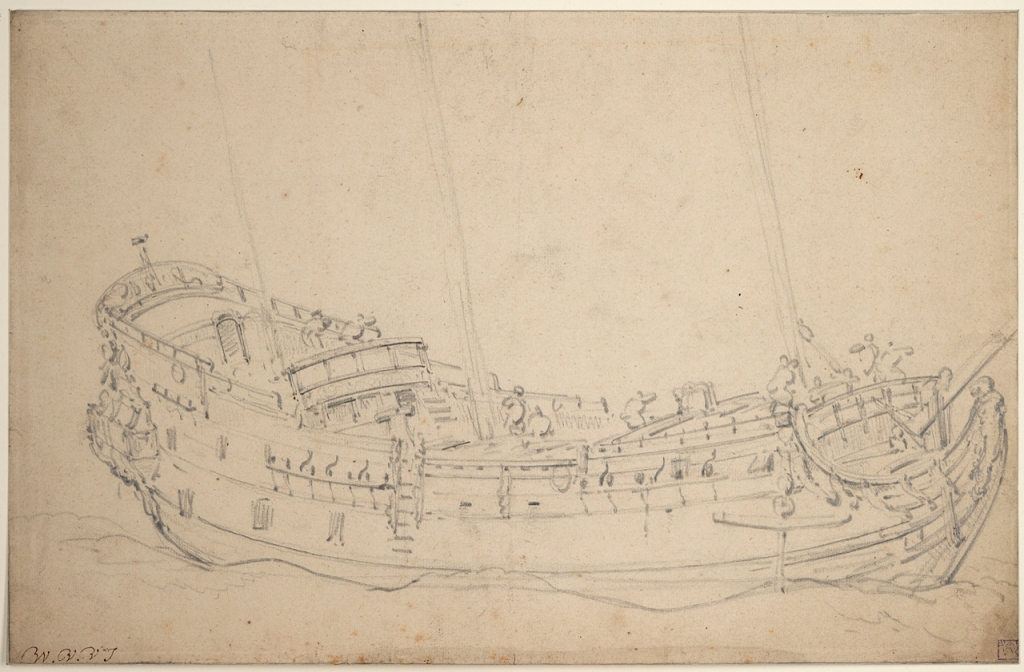

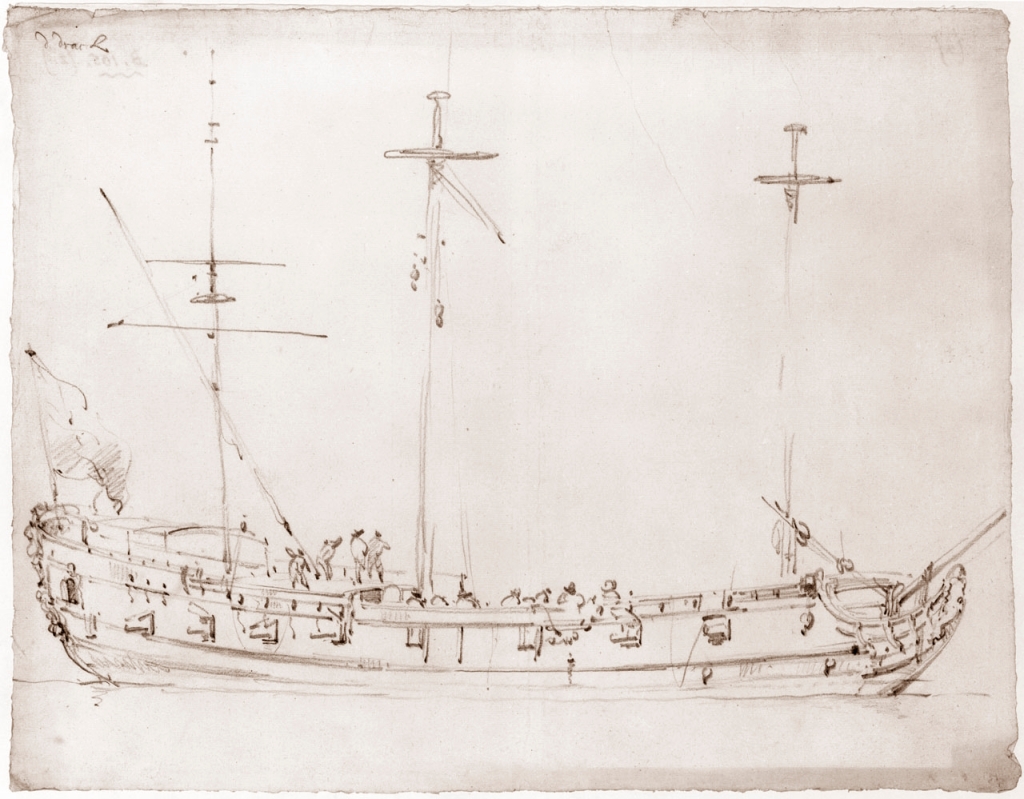

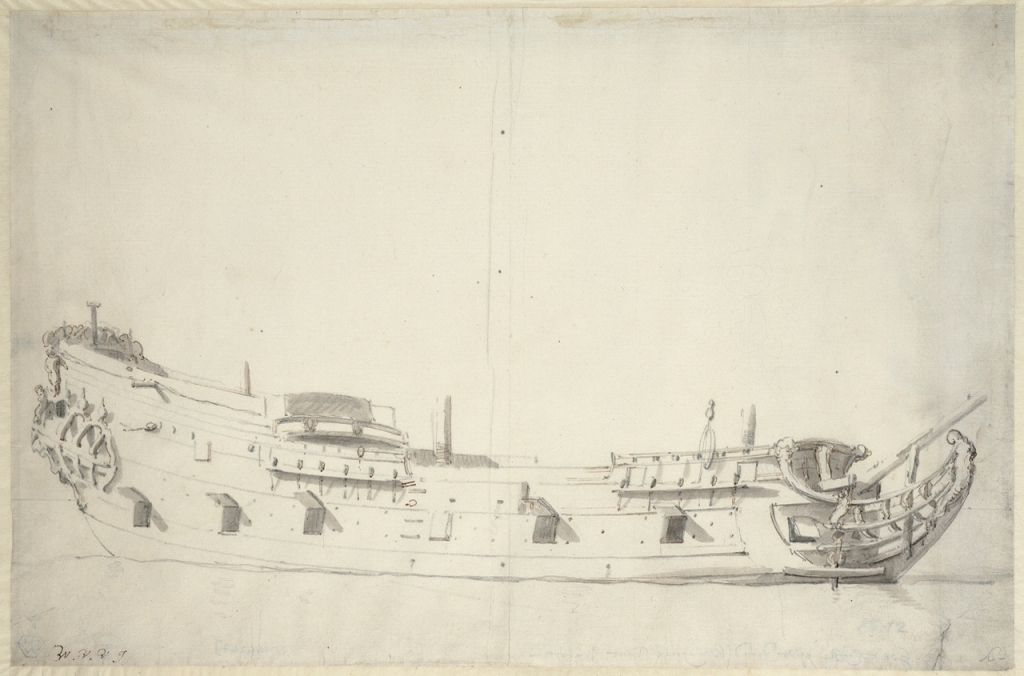

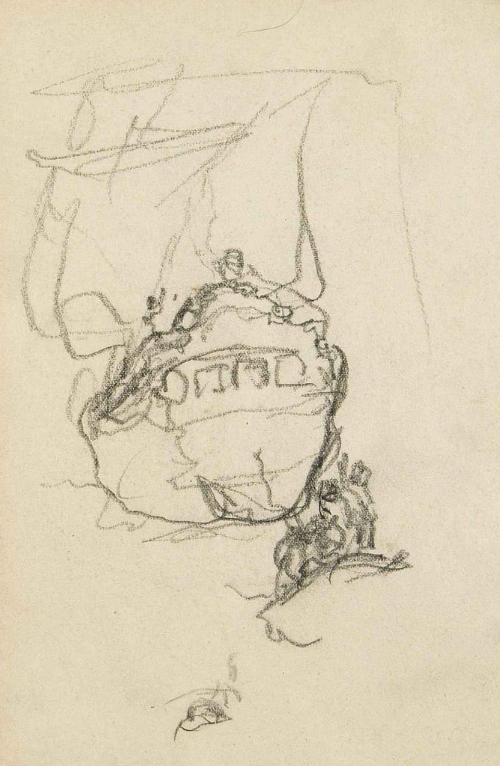

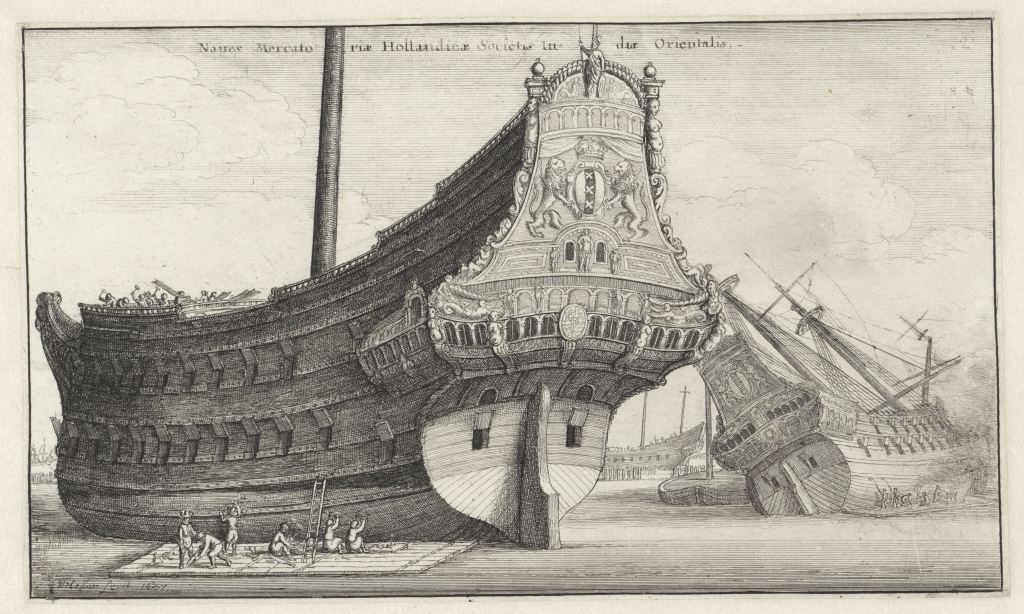

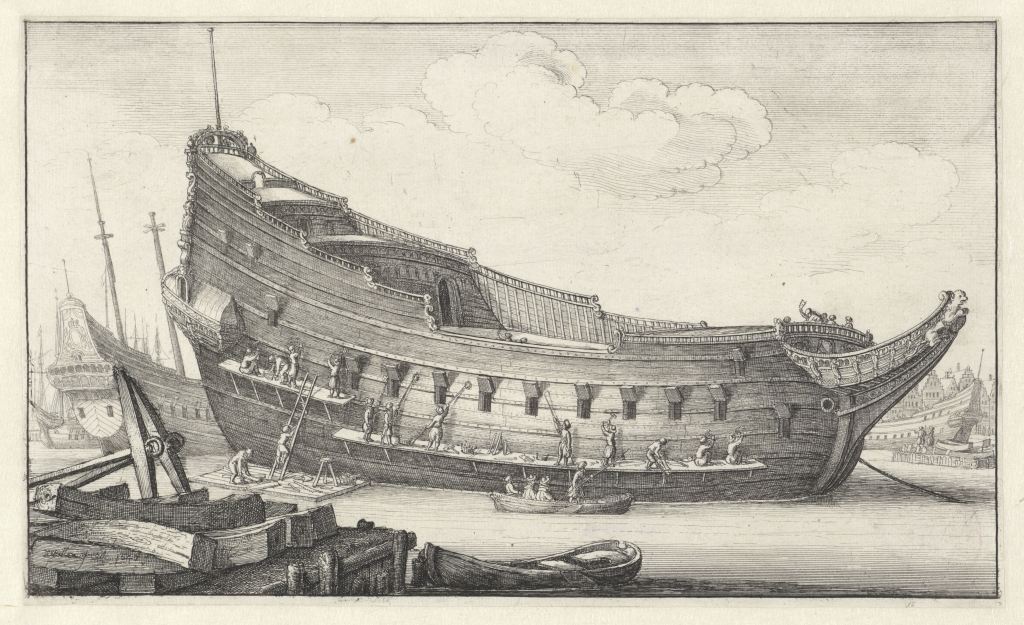

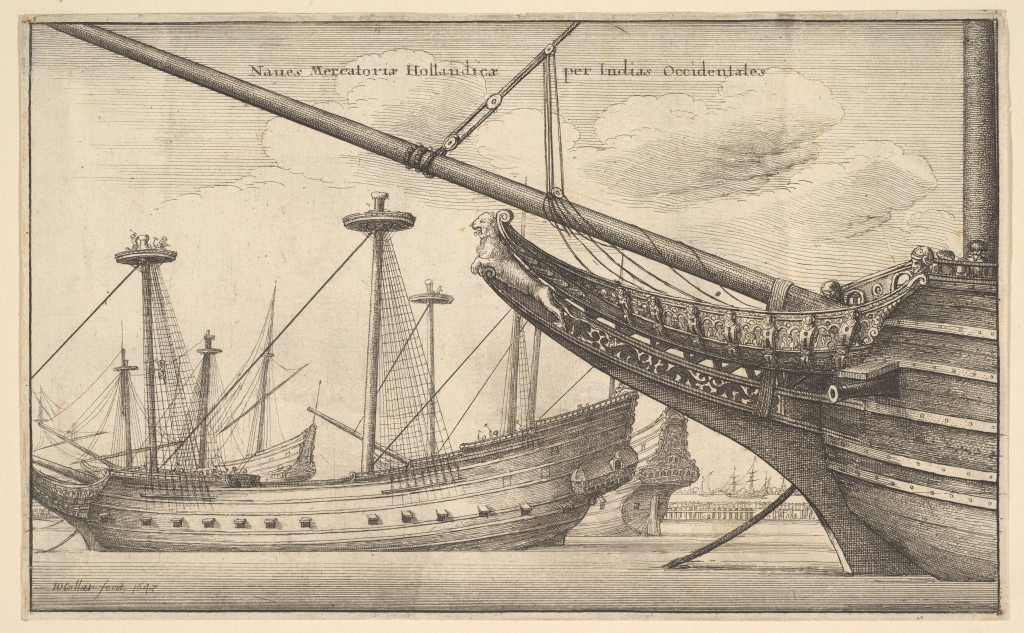

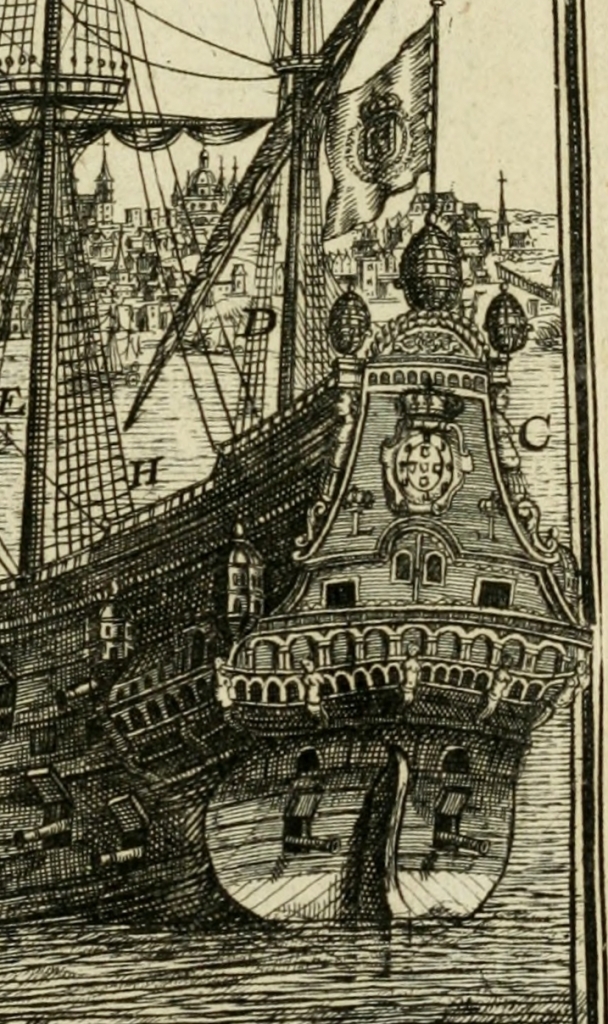

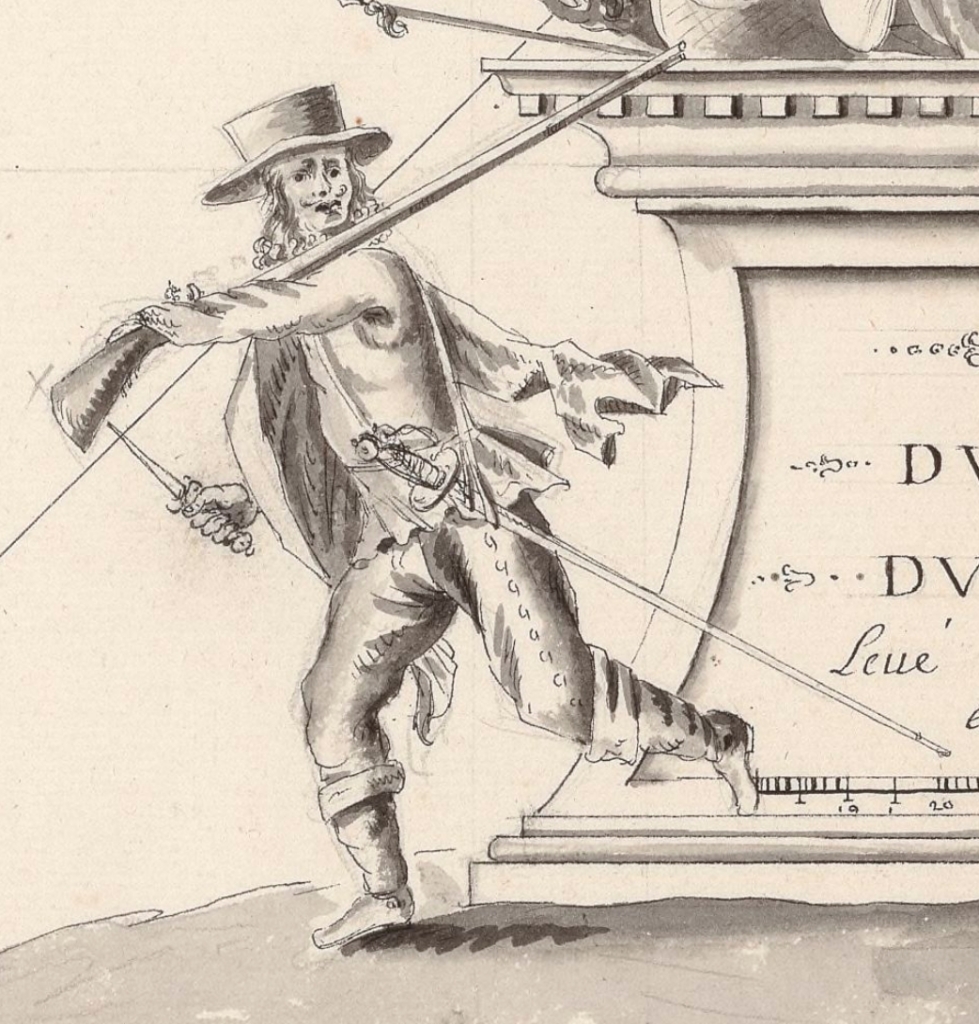

From the left drawing above it’s easy to see that Pyle changed the early conception of the galleon’s stern, eventually elongating it greatly for effect. Even so, the stern is historically-based. Without any doubt, as his inspiration Pyle used the well-known illustration, shown below, by 17th century Dutch artist Wenceslaus Hollar in 1647, and with poetic license narrowed the stern even further. Not only is the Hollar drawing quite similar, but Pyle used it in a later illustration, copying it almost exactly.

The illustrations by Hollar below show a form of mid-17th century Dutch ship used for both East and West India voyages. By the 1660s Dutch sterns, had become a bit lower and less narrow at the upper transom. Even so, some of the East and West India-men shown below, built in the 1640s and 1650s, would have survived in the 1660s and even 1670s or later. Importantly, approximately one third of Spanish ships were Dutch-built, including some treasure ships sent to the Americas, making Pyle’s Dutch-style Spanish galleon historically-correct, or largely so.

In the comparison above, Pyle has largely kept the structure and decoration with minor modification. Importantly and correctly, he has added a large Catholic religious icon representing the ship’s name at the stern. This was the usual practice aboard Spanish ships of the era, nearly all of which had religious names although some had secular nicknames. So far, the only exception I’ve found to the religious name rule is among some Spanish privateers. Occasionally, a religiously-named Spanish privateer or man-of-war might display the Spanish arms as its main icon at the stern, but it would still display a religious icon representing its name somewhere below or above the arms. Here we can assume that Pyle’s galleon’s name begins with Nuestra Señora given that the icon appears to be of Madonna and Child.

It’s possible that Pyle may have been originally inspired by “Wager’s Action off Cartagena, 28 May 1708” by English painter Samuel Scott. Painted at some point in the 1740s, Scott depicts a classical 17th century Spanish galleon, although in fact the galleon in question, the San Jose, whose remains along with possibly a billion dollars in treasure, are currently undergoing careful salvage off Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, probably looked nothing like this. (Details in the section below on real galleons.) In any case, Pyle may have been familiar with this famous painting, and sought out similar but more detailed images, and found those of Hollar. Notably, Pyle’s billowing smoke and orange colors are similar to Scott’s. (Compare with the image of what is probably the San Jose’s actual stern later in this post.)

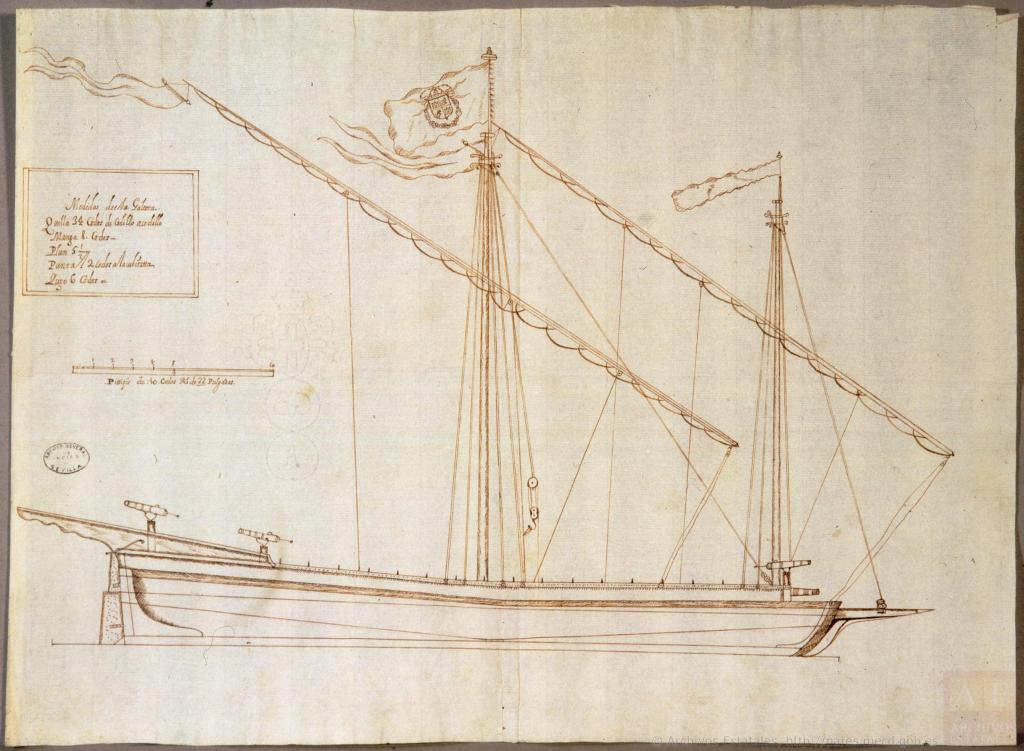

A word or two on the term galleon. Originally, in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, it referred to a stout ship with specific characteristics that was built for war and trade. Spanish galleons were noted in particular for their very high sterns. By the late 17th to early 18th centuries the term galleon could refer to (1) in its narrowest definition, a treasure ship of a type built to very specific guidelines for use in the Carrera de Indias (the trade to the Spanish Americas from Spain and from the Spanish Philippines), (2) any Spanish treasure ship of any sort, (3) any Spanish ship with a very high stern and multiple stern galleries, and (4) any ship of war or trade similar to those of Spanish galleons, in particular those of Portugal (occasionally still referred to as carracks as well), Venice, Genoa, and “Turkey” (the Ottoman Empire).

Further, some Spanish officials in the late 17th century incorrectly referred to Spanish men-of-war of the frigate type as galleons, retaining language from earlier in the century. True Spanish galleons, as described in (1) were largely no more by the 1640s except for a small number specifically built for the treasure fleets. Arguably, the last true galleons, and there were but few by this time, were built in the 1690s, yet privateer Woodes Rogers in A Cruising Voyage Round the World (1712) describes one in the first decade of 18th century in the South Sea (the Pacific Spanish Main): “[S]he was call’d the Ascension, built Galeon-fashion, very high with Galleries, Burden between 4 and 500 Tun…” He later refers repeatedly to the ship as a “Galleon” — and oddly, to neither of the Manila galleons as galleons, but only one or the other as the “Manila Ship.”

Although the life of a ship in this era was often less than twenty years, some were in use for thirty to forty years, ensuring that older forms of ships were still well-represented.

Pyle also painted a somewhat similar illustration in 1898, published eventually in Collier’s magazine, December 10, 1904, and it clearly shows that his inspiration was taken from Hollar’s Dutch East Indiaman.

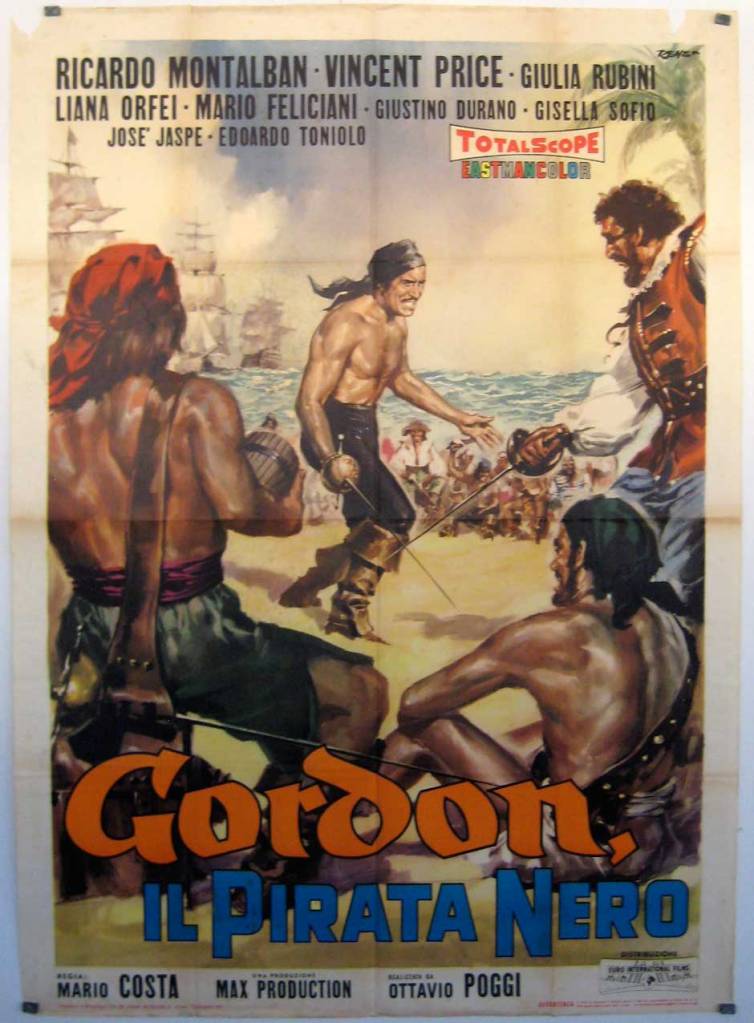

Imitations & Homages

Pyle’s galleon, or its inspiration, has spawned numerous imitations, right down to the present. Many, most perhaps, are homages. Below are a few representative images.

His treasure ship has often been used in advertising, for example in this add from The Saturday Evening Post, October 22, 1927, for 1847 Rogers Bros Silverplate. “Time and Tides are Kindly to Comely Captain Housewife,” reads the caption. Sexist, yet the series of ads does feature a variety of often clearly independent pirate women as opposed to more common images of domesticity. Doubtless the illustrations of sexy pirate women were intended not only to attract the attention of women readers, but also as lure to inspire husbands to buy the cleverly marketed “Pieces of Eight” set of silverware and associated pieces.

The detail below clearly shows the galleon to be a copy of Pyle’s famous ship. An homage, probably, but also good marketing, immediately evoking the pirates and buccaneers of Howard Pyle and Douglas Fairbanks.

A dinner plate dating from 1923 – 1936 — an era of cinematic pirate adventurers Douglas Fairbanks and Errol Flynn, and the buccaneer novels of Rafael Sabatini and Jeffery Farnol — shows likely influence of Howard Pyle’s galleon. That said, as seen above, there were real ships with similar sterns.

I almost forgot about several famous galleons, at least one of them an English one, all painted by N. C. Wyeth — perhaps Howard Pyle’s most famous student. All clearly evoke Pyle’s galleon. Homages from student to teacher, without doubt.

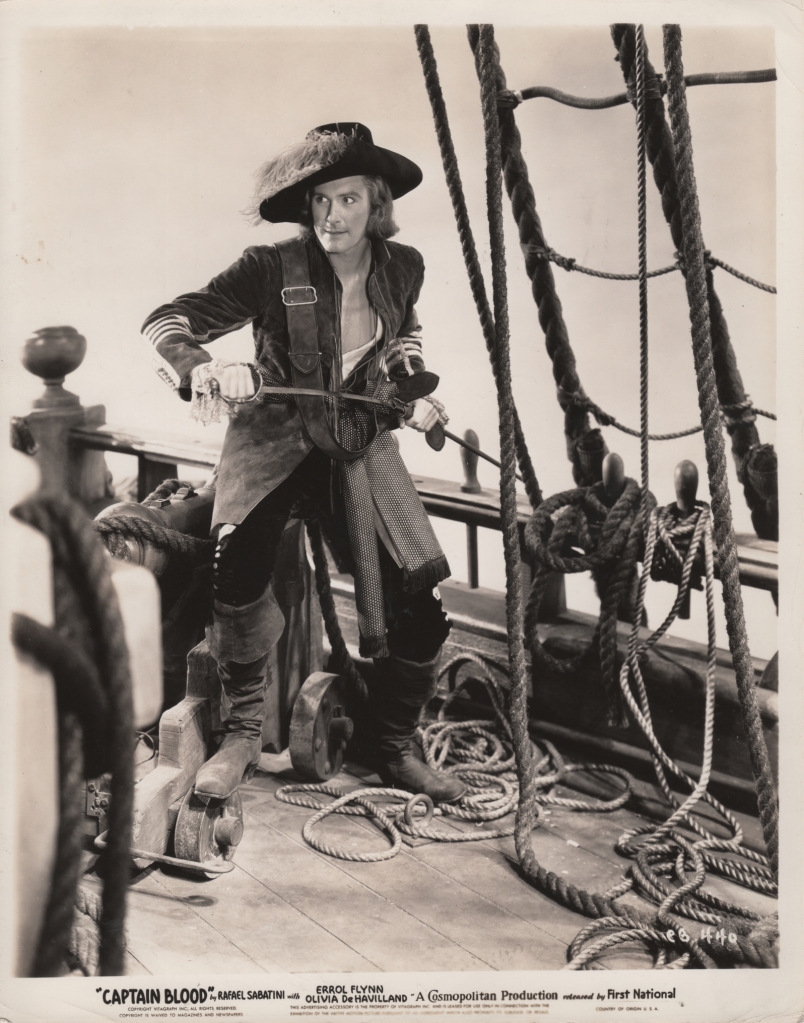

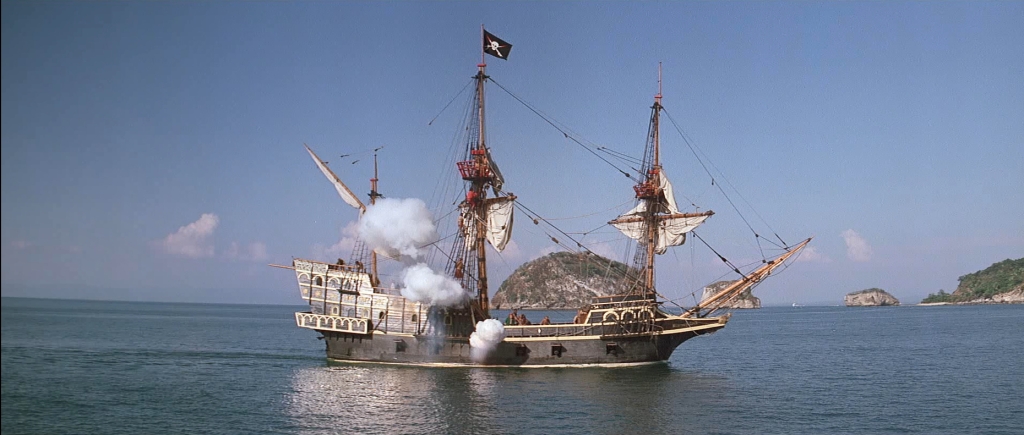

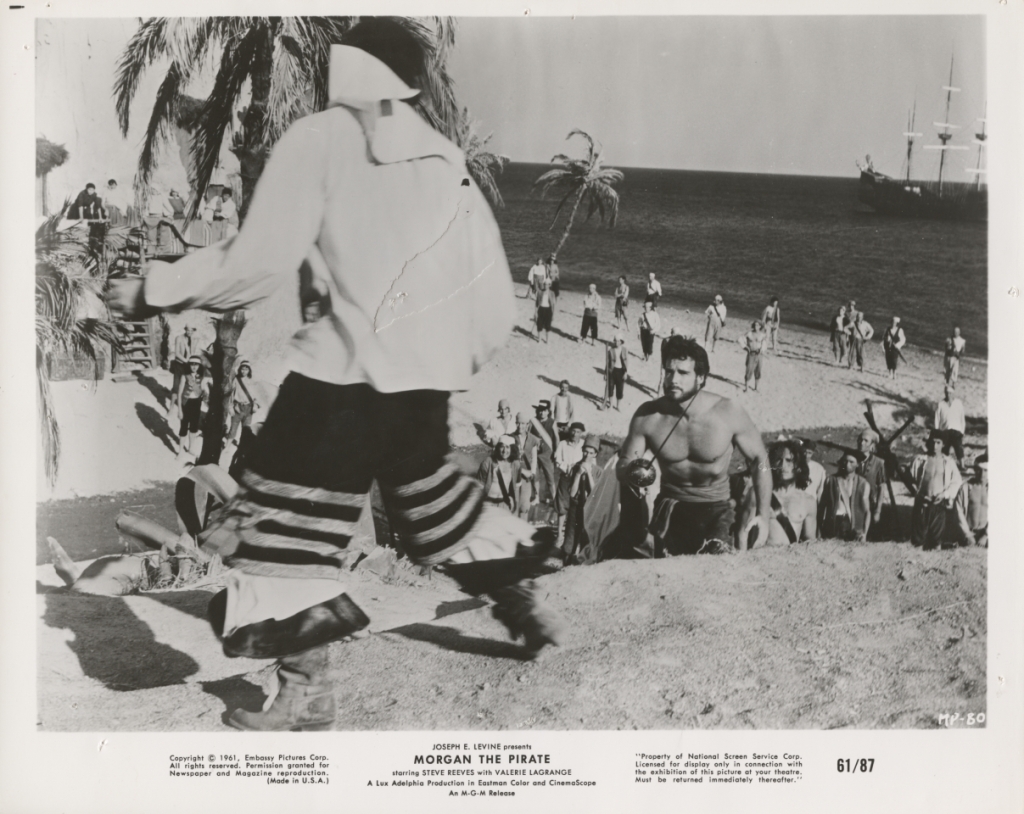

I cannot decide if the Cinco Llagas aka Arabella of the 1935 Captain Blood was inspired by Pyle’s painting or not. Without doubt the designers were familiar with Pyle’s galleon, although technically the Arabella is a frigate.

Likewise the Wicked Wench, which was clearly inspired by the Arabella, as I’ve discussed here.

Even so, the galleon — surely the Arabella! — in this 1935-1936 Spanish poster for Captain Blood (Warner Bros., 1935) was copied from or inspired by Pyle’s famous galleon. And appropriately so, given Pyle’s overwhelming influence on pirate films of the era. Note that the forecastle appears to have been appropriated from any of many N. C. Wyeth Elizabethan galleons, or even earlier galleons.

The stern of the Spanish galleon in The Spanish Main (1944) starring Paul Henreid and Maureen O’Hara may well have been influenced by Pyle’s painting, in particular the ascending pointed carved decoration at the top of the stern transom. Compare with that of the Urca de Lima in the television series Black Sails later in the post.

Famous science fiction and fantasy illustrator Frank Frazetta honored Howard Pyle with an homage to his famous galleon.

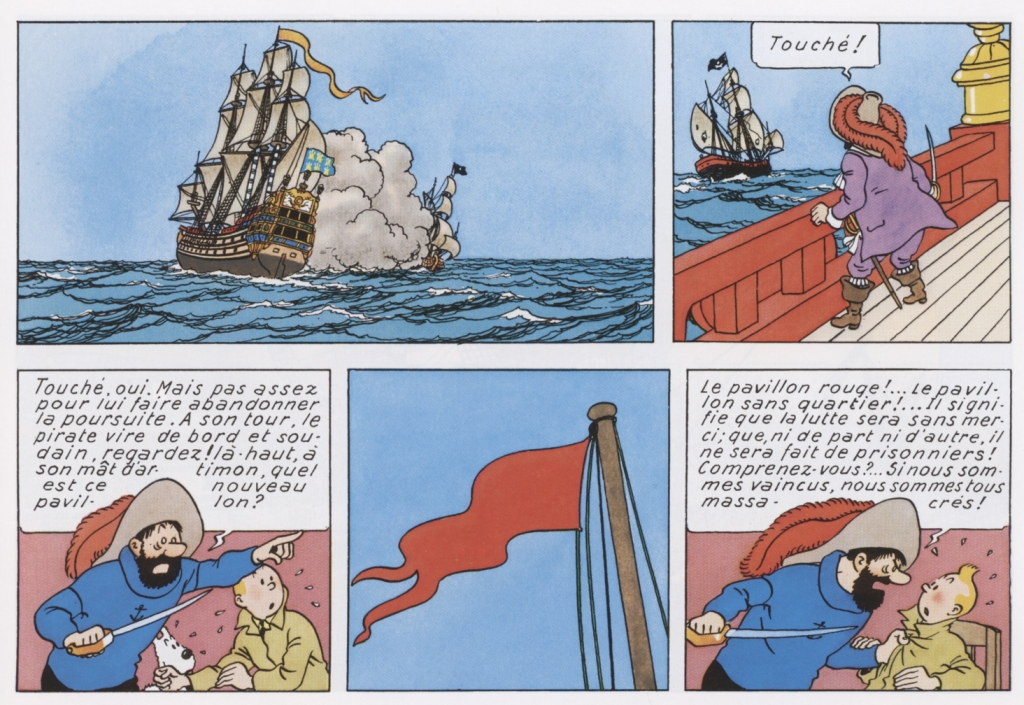

N. C. Wyeth’s grandson, Jamie Wyeth, a famous and outstanding painter in his own right and son of iconic artist Andrew Wyeth, did the artwork for the plate below, a clear homage to both his grandfather and to the man who taught his father, Howard Pyle. In this case it is a “pirate galleon” — clearly a Spanish galleon fallen into the hands of buccaneers per classic trope. (N. B. Buccaneers didn’t fly the black flag with skull and bones, although at least one crew did fly the red banner of no quarter with skull and bones. But it’s the image that counts in storytelling, and we’ve come to expect the black flag on all pirate ships of all eras. See The Golden Age of Piracy for more details.)

Almost certainly the “galleons” (they appear to be manned with English marines) below, especially the one of the left, in this art by cartoonist François Ruyer for a puzzle is an homage to Pyle’s famous painting, with their excessive height and pirates attempting to board one of them via boat. Even the sky color evokes Pyle’s painting.

Likewise an earlier image by Jean-Jacques Loup for Heye, “Captain Flint’s Party,” for a puzzle evokes galleon sterns reaching for the moon, so to speak:

It’s entirely possible that Pyle’s galleon even influenced the design of the Urca de Lima in the Starz dramatic series Black Sails, shown below. (Compare also to the galleon used in The Spanish Main above.) Although I was the historical consultant for all four seasons, I don’t know this for certain as I had no input into sets, including ship design, unfortunately — otherwise the ships might have been more historically accurate. Some of them in reality would not have been seaworthy.

And on a nitpicking the note, urca is the Spanish word for a type of ship originally designed by the Dutch but in use by all Western European seagoing nations. It was known as a fluyt, flute, flutte, or, in English, a pink. It had a rounded stern, not a flat one as the television galleon has, and a very small narrow transom (which might have provided some additional excuse for Pyle’s very narrow upper section of the transom for his Spanish galleon, even though it’s not an urca). In other words, the Black Sails galleon should be an urca instead. It bears noting that an urca is NOT a galleon — yet one might be referred to colloquially as a Spanish galleon if carrying Spanish treasure…

But I digress a bit under the influence of historical accuracy! Even so, this brings us to a good subject: what did Spanish galleons and their sterns actually look like from 1650 to 1700?

Spanish Galleons 1650 to 1700

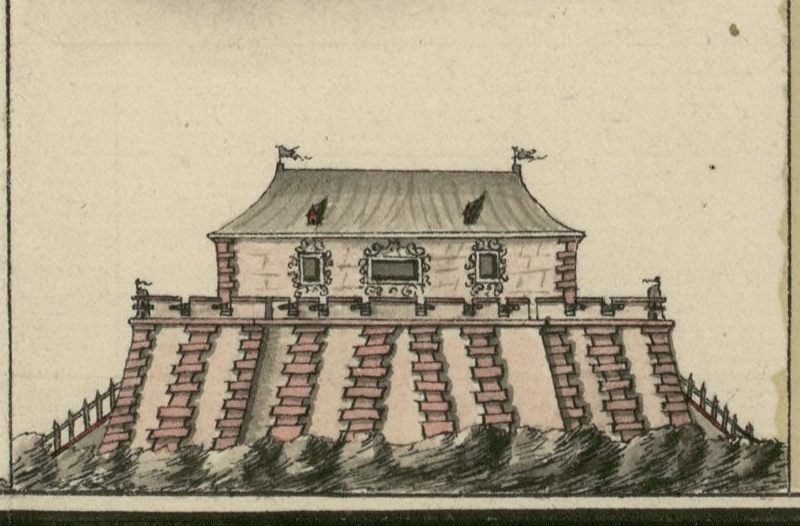

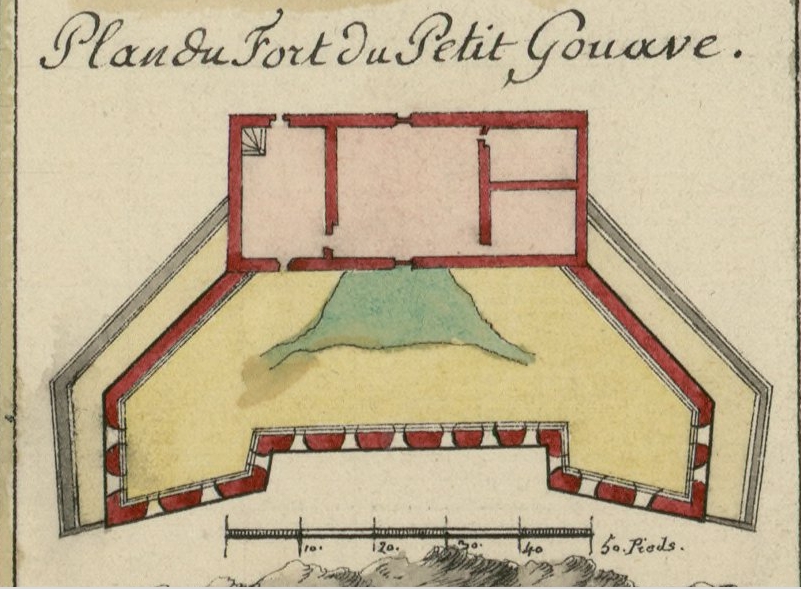

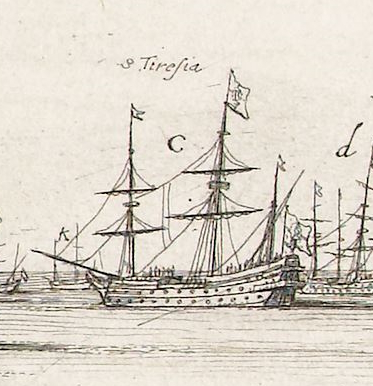

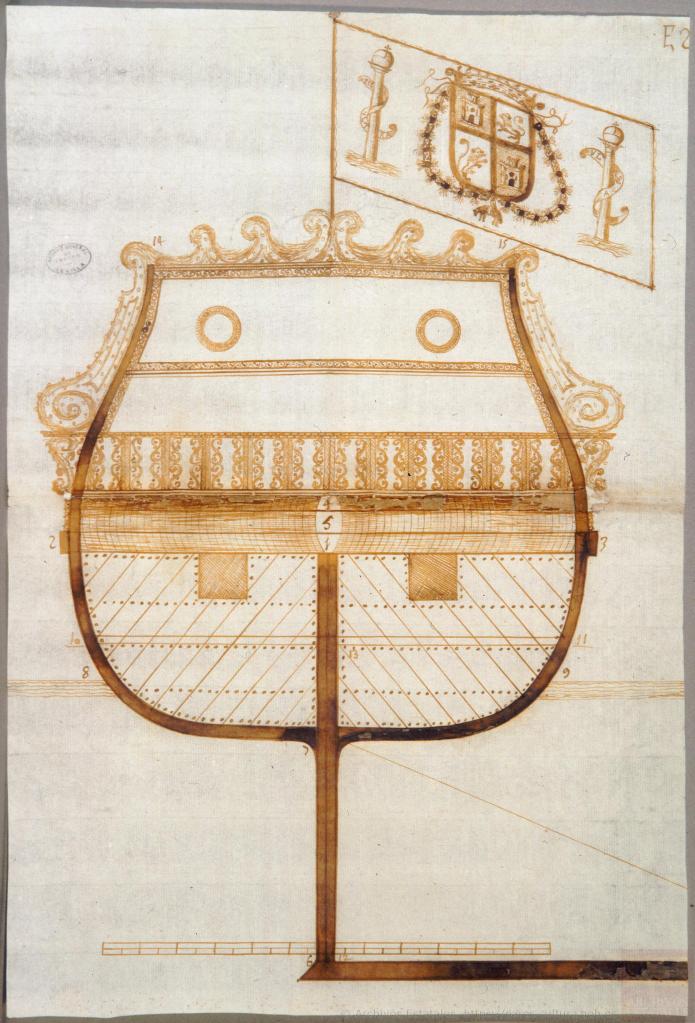

For the first forty years or so of the 17th century, the large or main transom of Spanish galleons was typically “stepped” (in layman’s language), with the upper part or parts overhanging the lower, rather than flat as soon would be the case. The Spanish galleon Santa Teresa, shown in the three images below, is a good example of this style of very common early 17th century Spanish sterns.

The “Vista de Sevilla” (“View of Seville”), circa 1660, artist unknown, gives us a good view of the sterns of Spanish galleons with enclosed galleries, and the changes that came mid-century. The sterns, although still very high, all now appear “modern” in the sense that the double transom, the upper overhanging the lower, has disappeared.

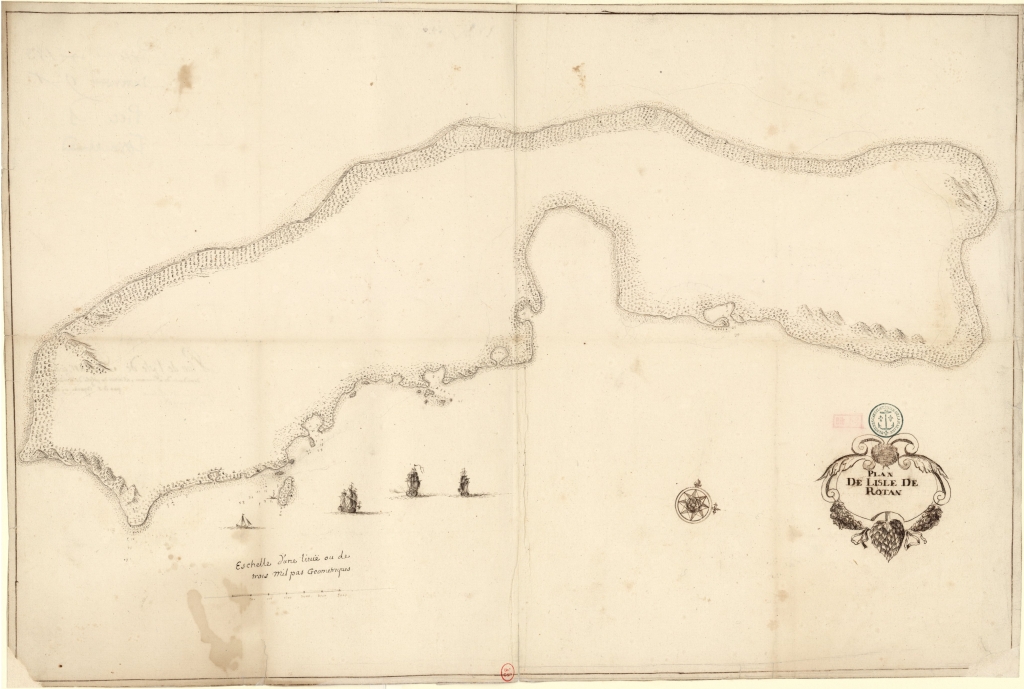

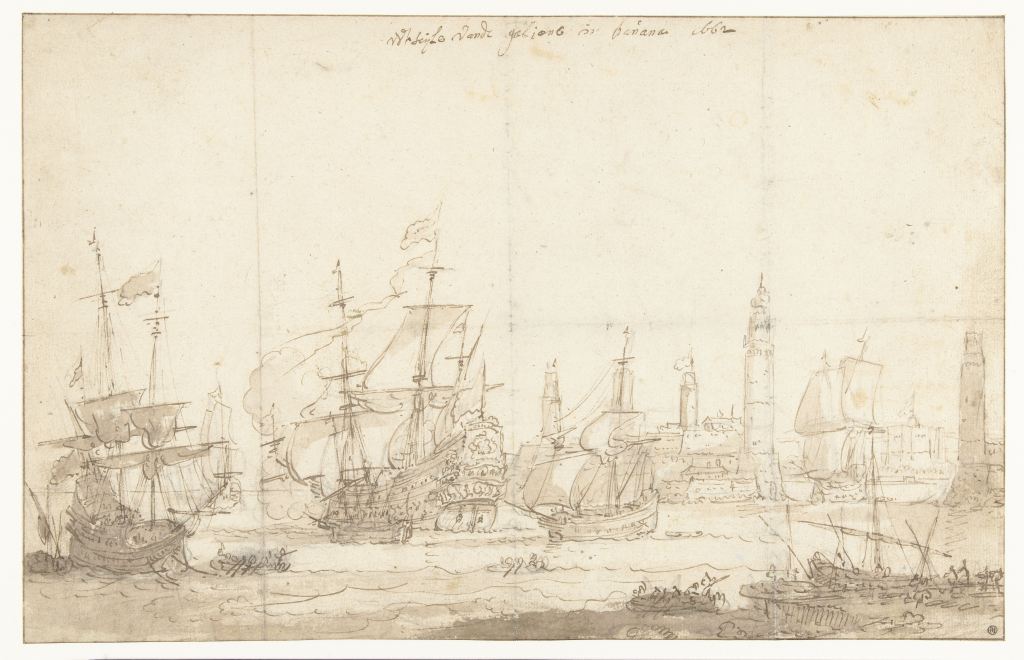

Below is an illustration of “The Spanish fleet sailing from Havana in 1662.” However, neither the Flota de Nueve Espana nor the Flota y Armada de Tierra Firme sailed from Havana in 1662, nor was it likely that either fleet was there at any time that year. More likely, the year was 1661 or 1663. Note the very high sterns of the two larger ships.

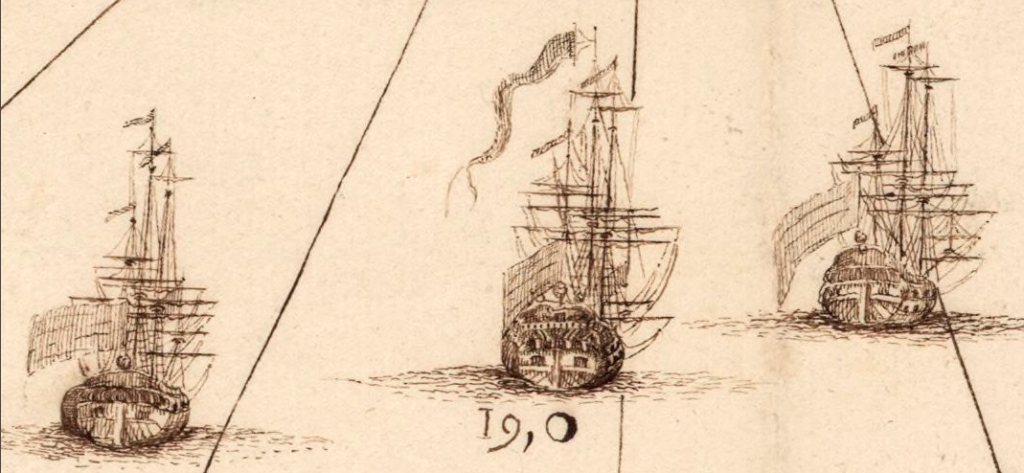

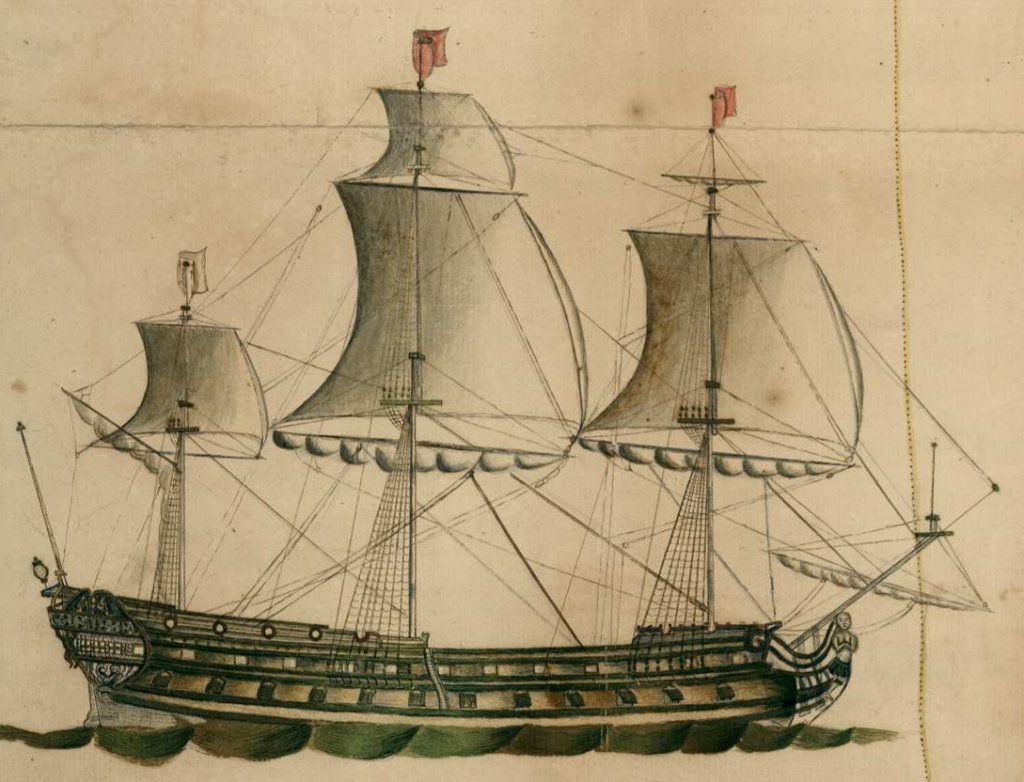

Below is an unidentified Spanish two-decker man-of-war dating to the 1660s. Although a frigate rather than a true galleon, the ship shows many of characteristics of Spanish galleons, and men-of-war as shown below often carried Spanish treasure and escorted treasure ships, earning them the appellation of galleon even if incorrect. Note the high stern, the religious iconography, the clinker planking on the upper-works, the channels mounted above the upper gundeck ports, the musketeer loopholes in the waist (identical to Dutch practice), the jeer capstan on the forecastle, and the two open wraparound external galleries, known as corredores, typical of Spanish treasure ships although not always to be found.

Another Spanish man-of-war stern, 1660s, with two open stern galleries that wrap around the hull.

Below are three very similar versions of the galleon Nuestra Señora del Mar, San José y San Francisco, showing details of her shipwreck in the Bermuda Islands in 1691. The ship was launched in Pasajes, Spain in 1681. Of 862.5 Spanish tons (toneladas), she was mounted with only 29 guns, a not uncommon practice for a large Spanish galleon, for much of her space was taken up with cargo. Note the color scheme, the style of painted decoration, the painted scroll-work on the upper-works, and three open external galleries. Each was, per Spanish period references, probably only thirty-three inches deep. The uppermost is at the level of the poop deck or even the poop royal if there is one.

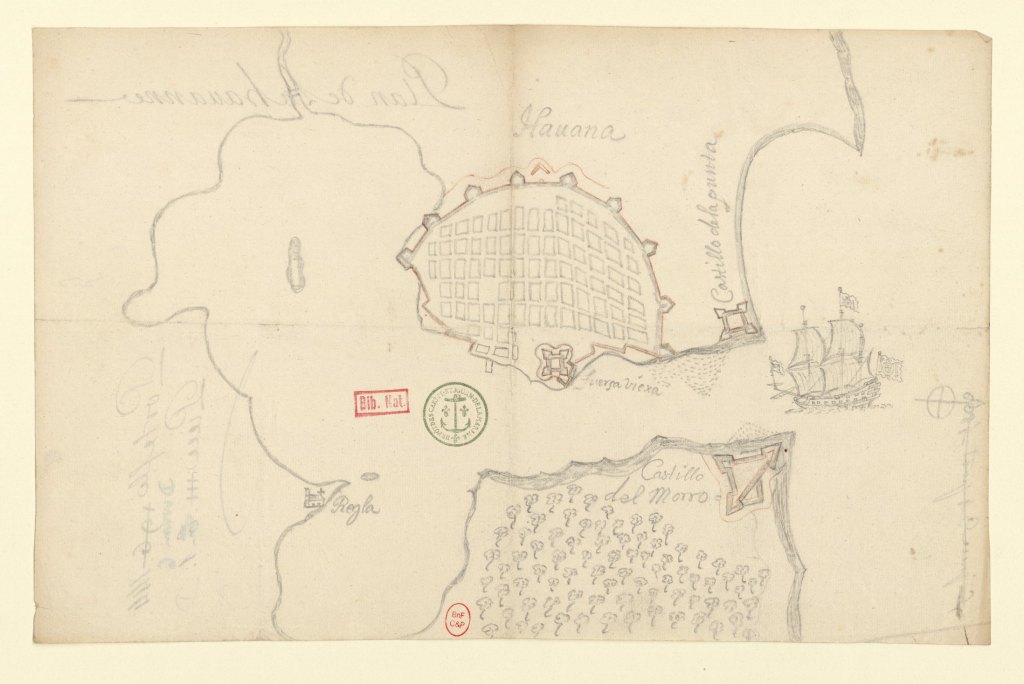

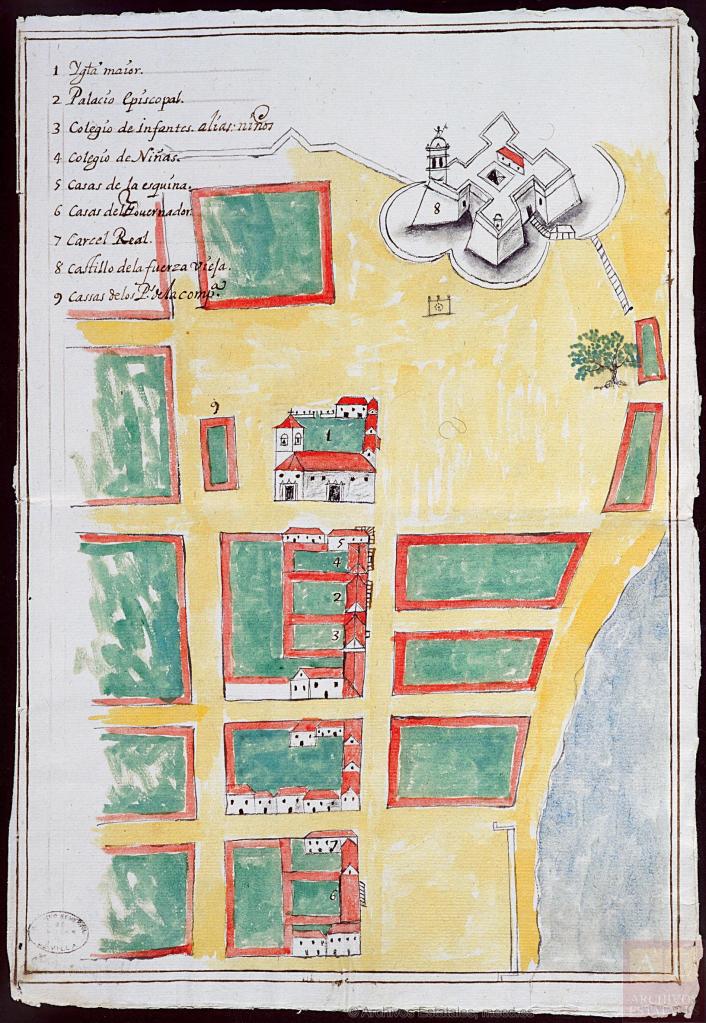

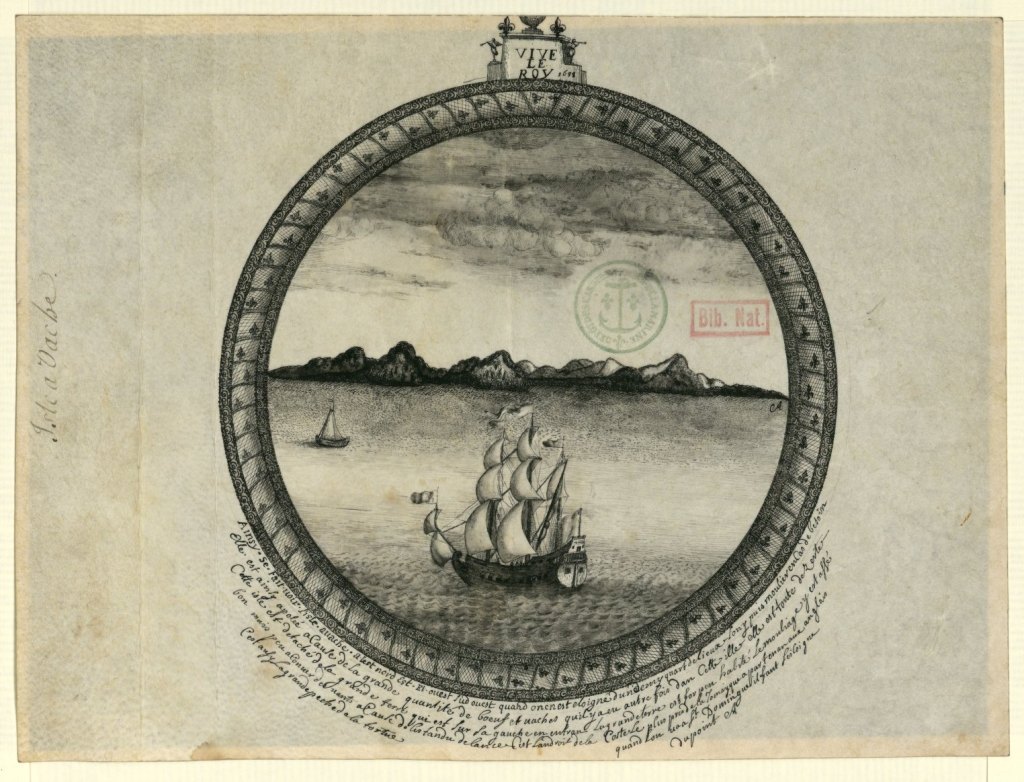

Below, a Spanish galleon with three open stern galleries, flying the royal colors, enters Havana harbor in the second half of the 17th century, probably 1660s to 1680s.

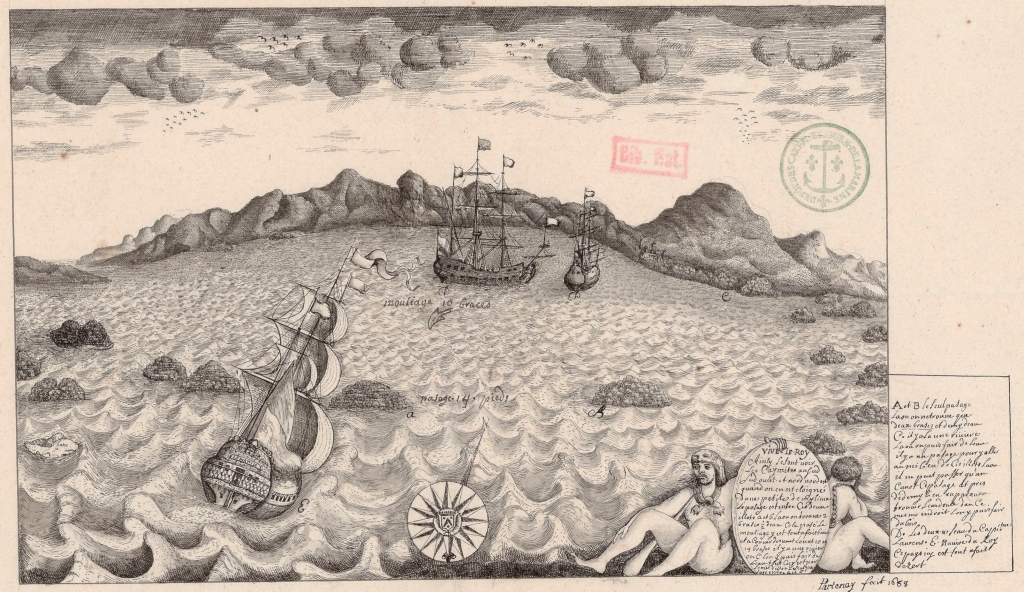

However, in spite of our romance with the open-gallery, high stern Spanish galleon, many did have the open galleries, but had closed galleries, or later, semi-closed, as seen just below in this Spanish galleon at Portobello, 1688.

As noted previously, ships of other nations were sometimes referred to as galleons in the second half of the 17th century, including some of those of Portugal (also occasionally still referred to as carracks as well), Venice, Genoa, and the Ottoman Empire (colloquially referred to as “Turkish” galleons).

The 1680s brought on changes in Spanish shipbuilding, including in its men-of-war and in its remaining true galleons. Although the latter often still had high sterns, they were soon reduced, more in keeping with European construction in general. And although galleons or treasure ships with multiple open, wraparound galleries or corredores were still seen, the enclosed gallery became much more common.

Below are Spanish treasure ships at anchor at Portobello in 1683. The multiple galleries and high sterns are clearly still evident.

The same treasure ships, or at least ships of the same fleet, at anchor in Portobello in 1682, as drawn by a different artist :

But the changes are coming. Below is a 1685 Spanish stern showing multiple external galleries, but without wrapping around the hull.

Spanish men-of-war, which often escorted treasure ships, and even carried treasure themselves, were changing, their designs becoming sleeker and more in line with other European navies.

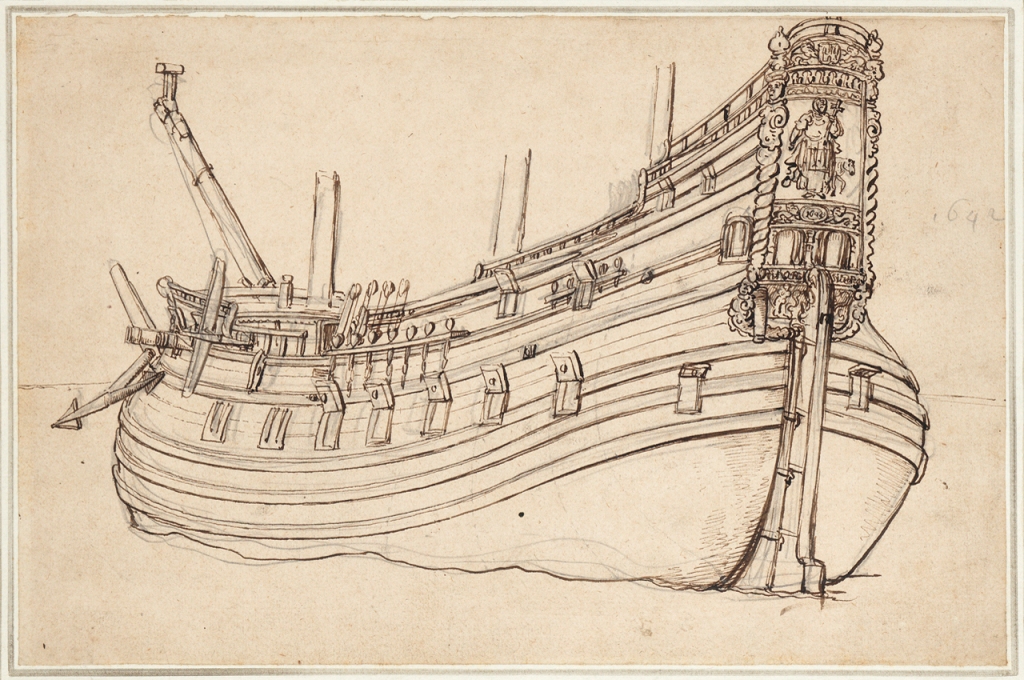

Below is one of a series of proposed Spanish men-of-war, 1691. Although never built, they reflect the new trends in Spanish ship design, including lower sterns and a semi-closed single stern gallery.

Even the last Spanish treasure galleons to be built had similar features. Below is the stern of what scholars generally believe to be the famous San Jose, launched in 1698 and sunk at Cartagena by Wager’s fleet in 1708, with a treasure aboard estimated by some to be worth as much as 17 billion dollars US today. Compare this drawing with Scott’s painting above of Wager’s action against the San Jose.

With the accession of a Frenchman to the Spanish throne in the early 18th century, over which the War of the Spanish Succession had been fought, Spanish ship design became more contemporary with that of other European sea powers. Gone was the conservatism that too often hindered Spanish shipbuilding. Below is a Spanish treasure ship of the new style. It has a projecting gallery that wraps around the stern (not all Spanish treasure ships and men-of-war had this), with a shade built overhead for the section of the gallery at the transom:

A closer look at these Spanish sterns in the first half of the 18th century. The stern gallery still wraps around the hull.

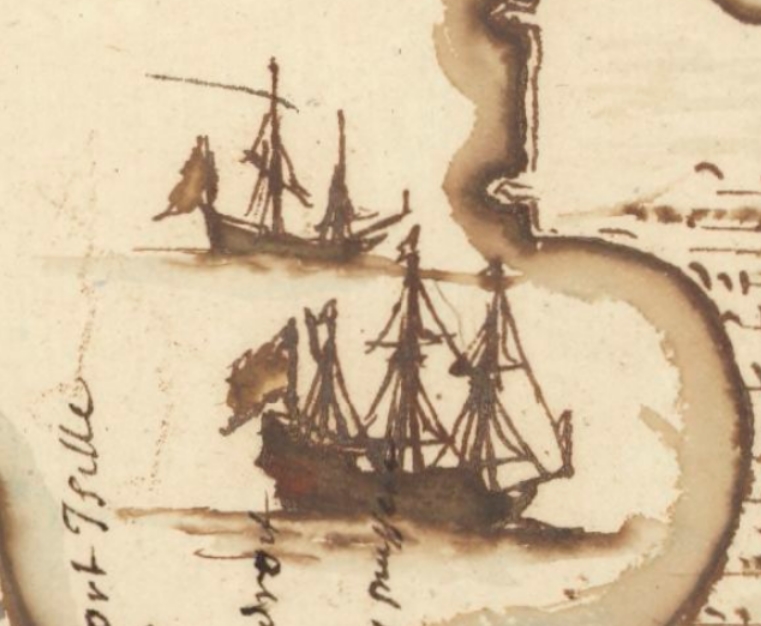

A simple pen and ink view of a Spanish man-of-war with what appear to be two projecting, probably wraparound, galleries, from a Spanish chart of Isla Vieques off the coast of Puerto Rico, 1721:

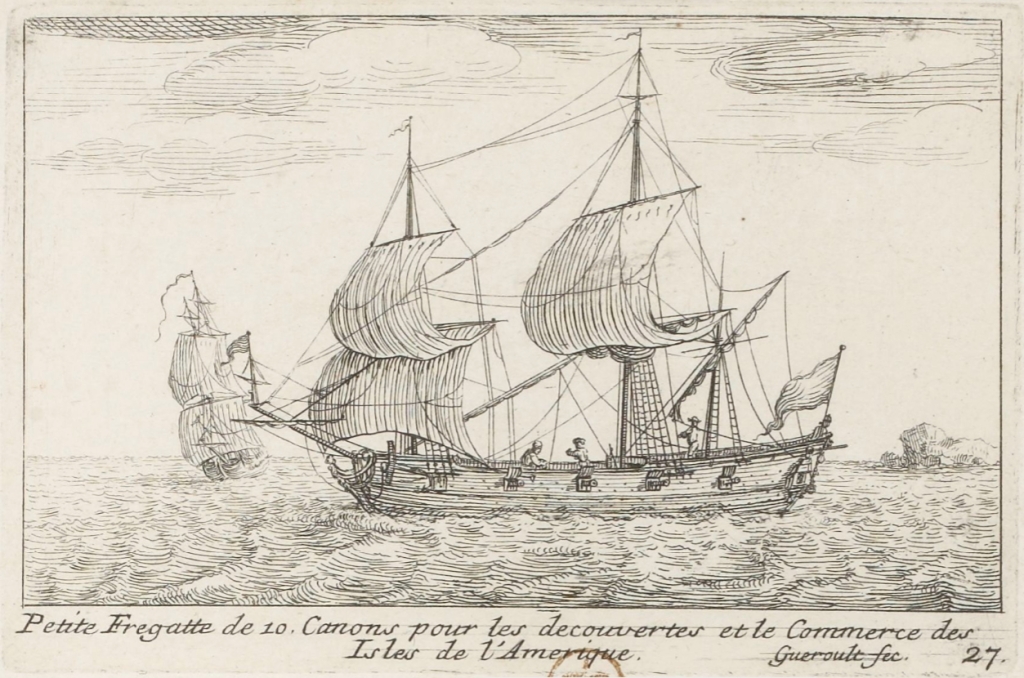

Design changes notwithstanding, the high-sterned Spanish treasure ship was in use into the first quarter of the 18th century. I’ve already mentioned Woodes Rogers’s description of one in the South Sea. Below is a depiction of a Spanish treasure ship by Gueroult du Pas in 1710.

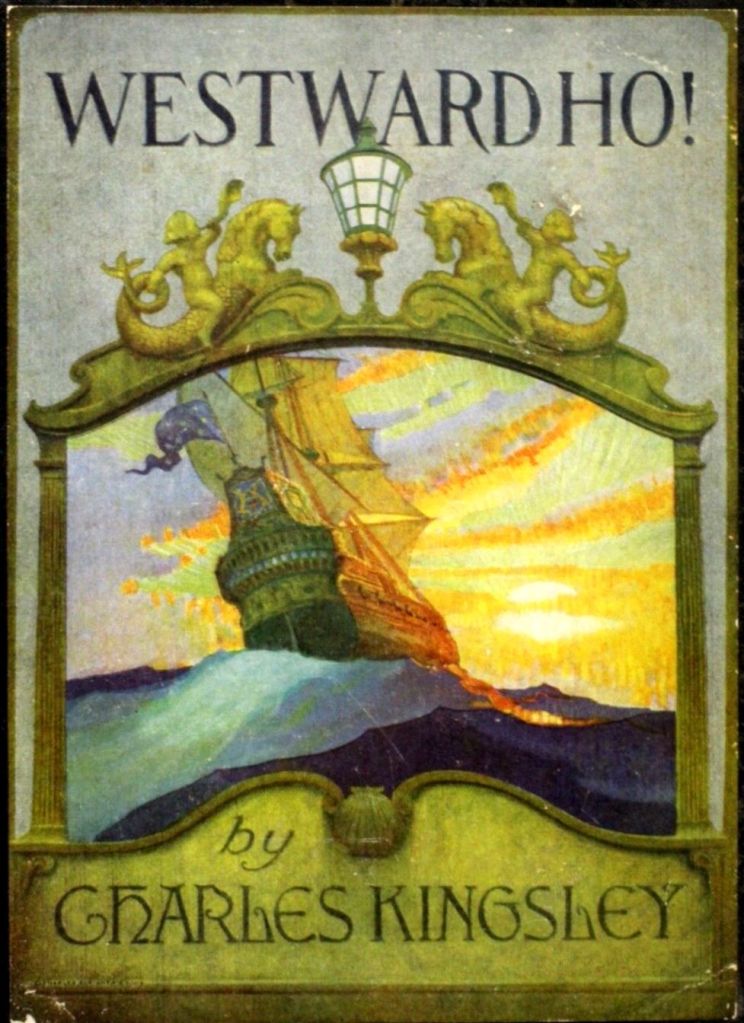

And it is these high-sterned Spanish galleons that always have captured our imagination, and continue to do so. Howard Pyle’s famous treasure galleon has helped to keep that imagination not only alive but enhanced. Even the romantically evocative dust jacket below must have been influenced by his famous galleon, with its high stern and colors of sunset or sunrise!

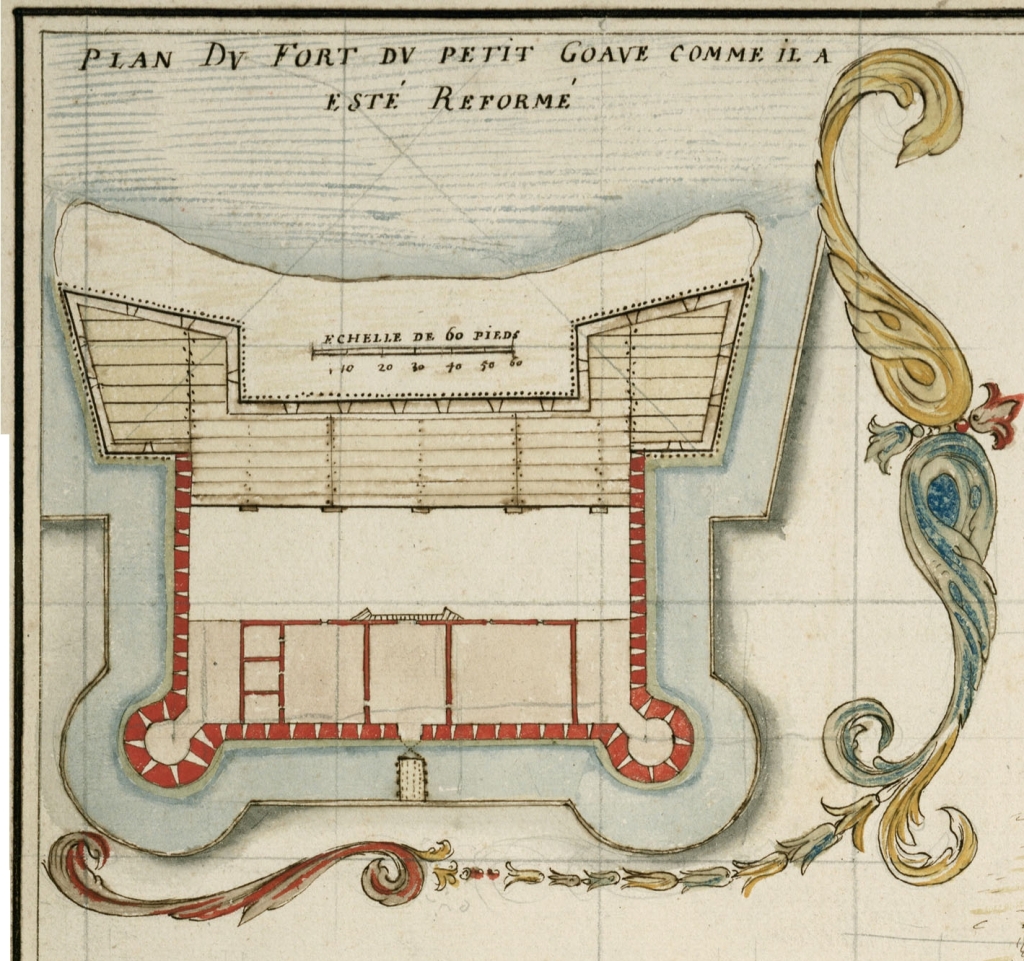

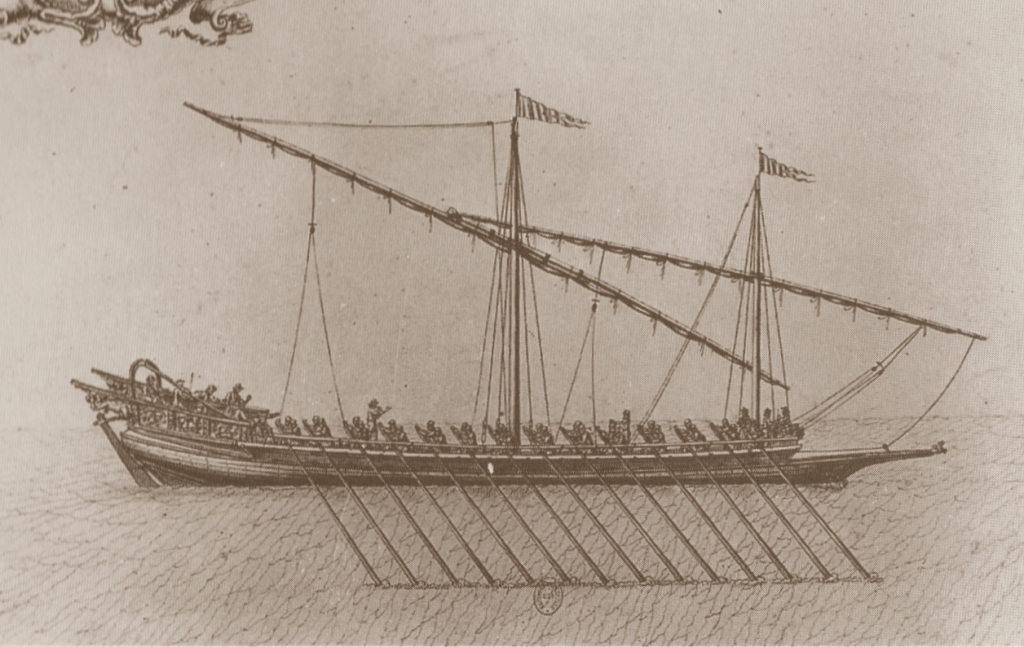

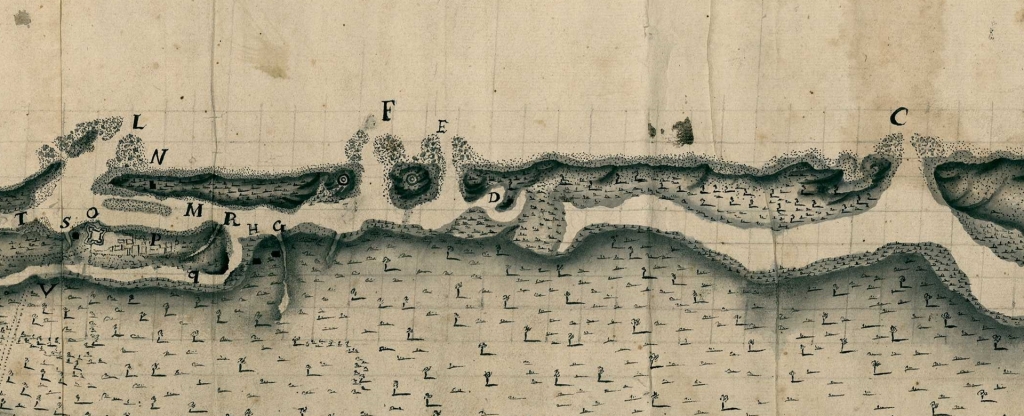

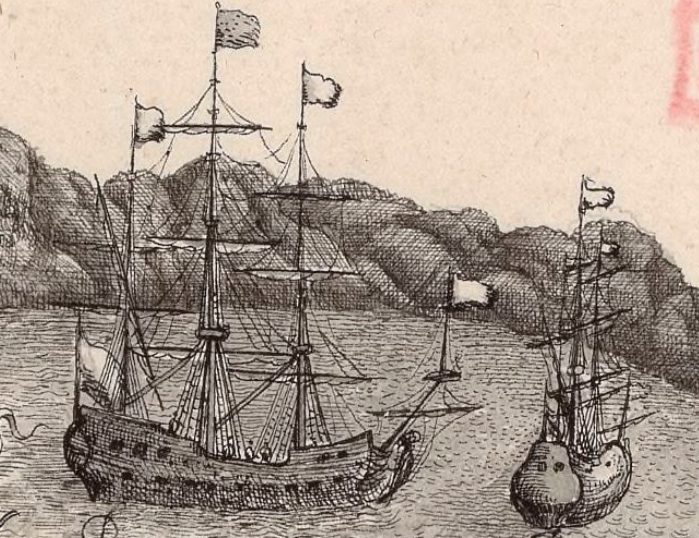

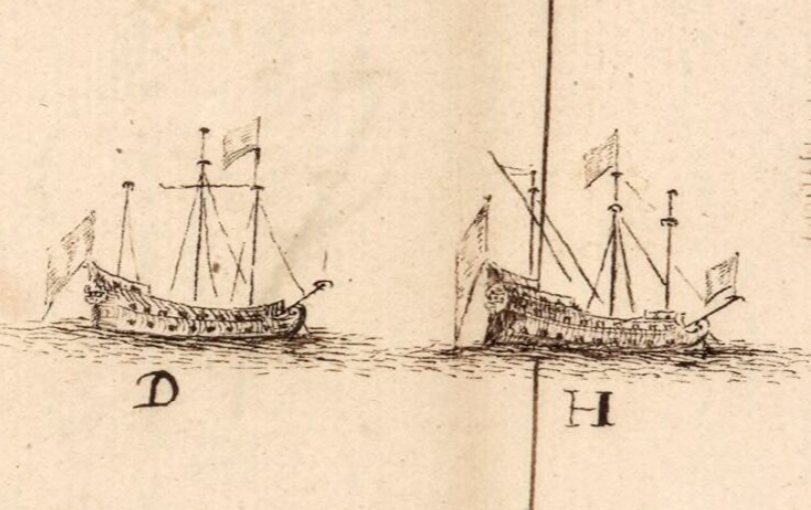

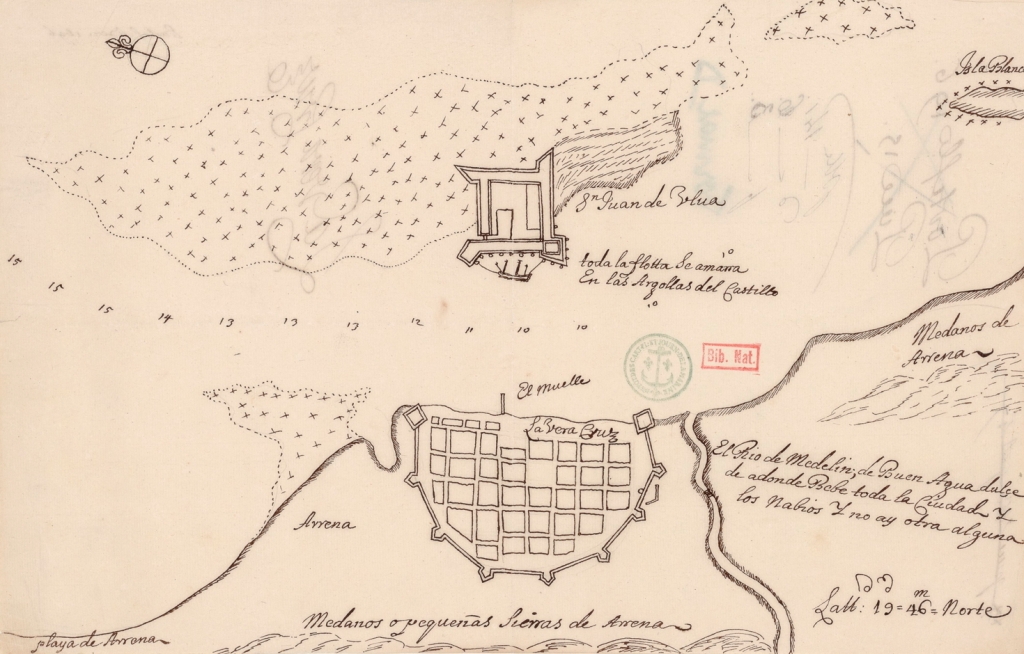

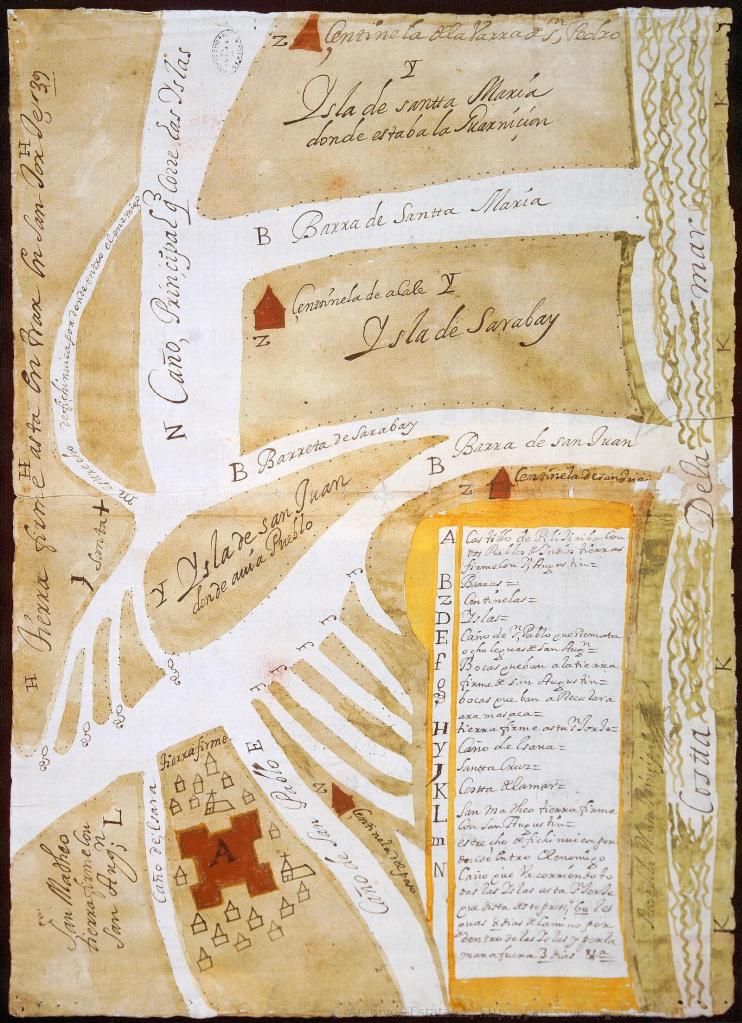

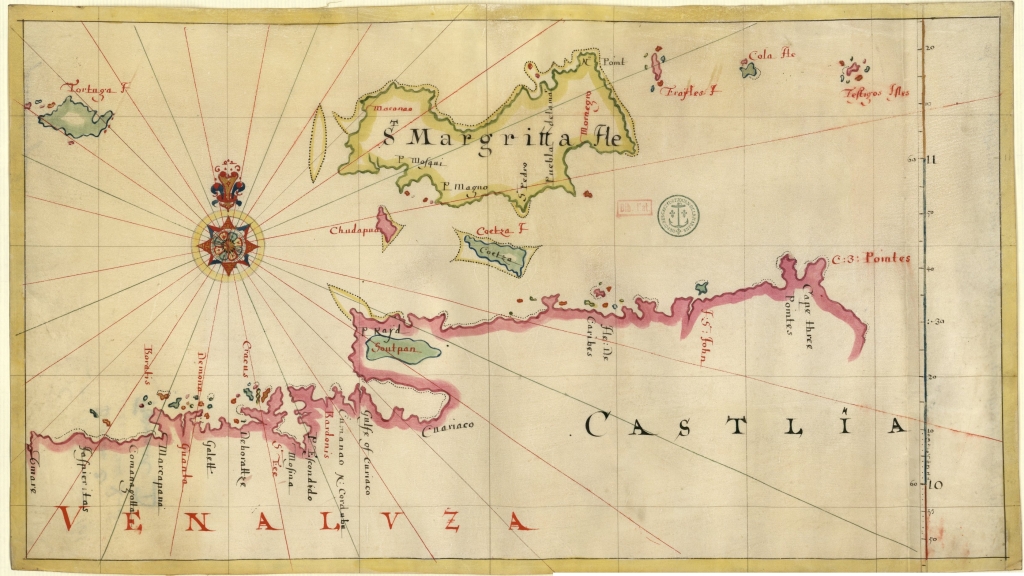

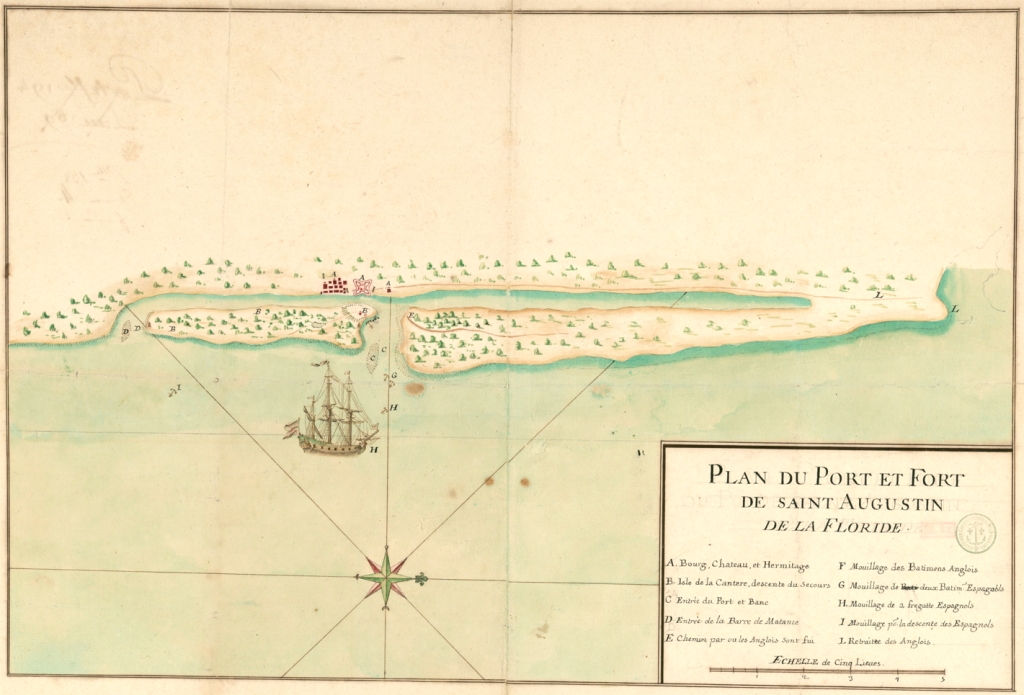

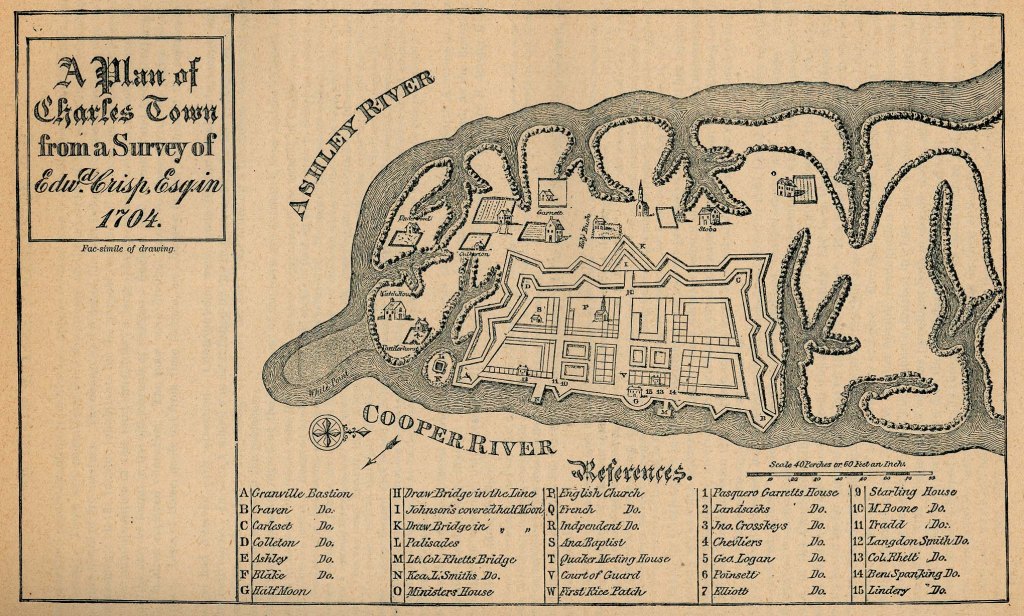

In fact, these iconic images of Spanish galleons from fiction, film, and more aren’t far off from those created by eyewitnesses in the 17th century, including these found on a Spanish 1669 chart of Cartagena de Indias!

Details from “Cartaxena con 46 piésas,” 1669, courtesy of the French National Library.

Copyright Benerson Little 2024. First posted March 27, 2024. Last updated April 25, 2024.

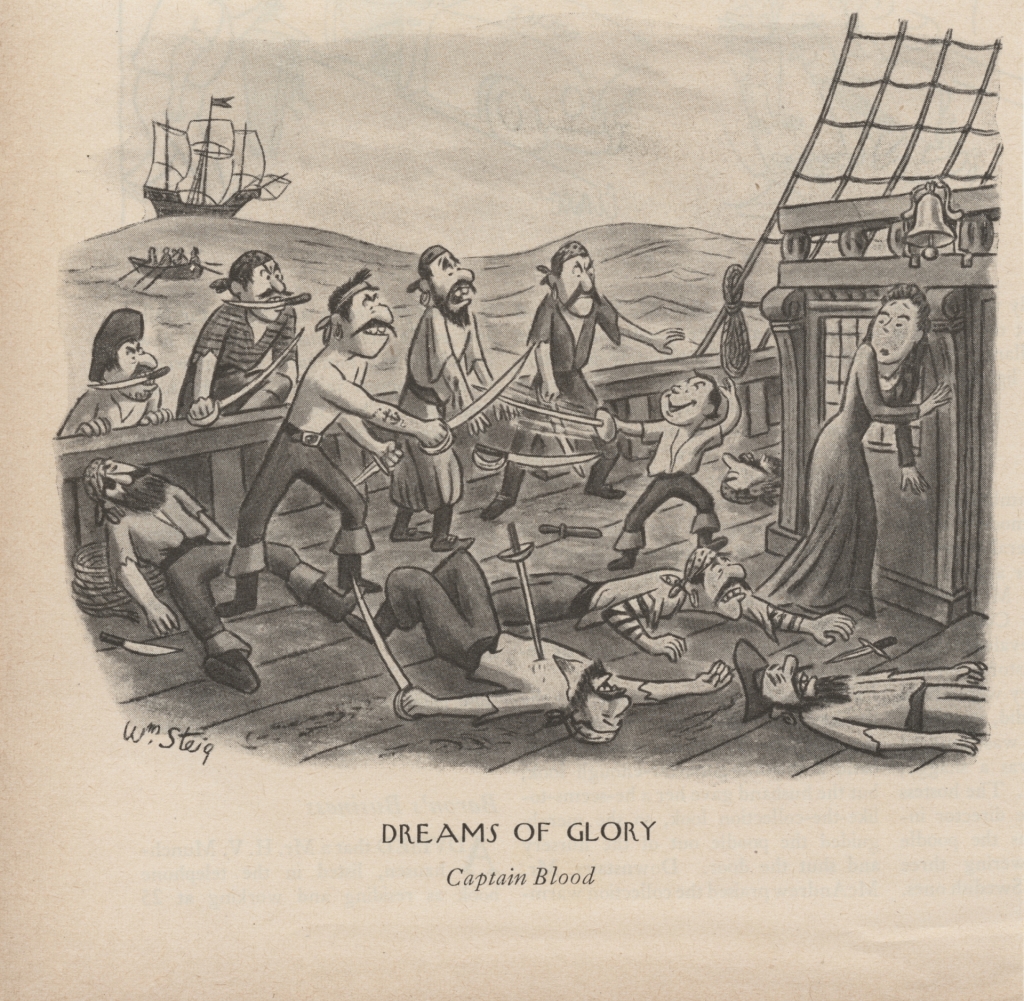

“Dreams of Glory” — Captain Blood! (Updated!)

I’ve seen myself in comics before — Calvin & Hobbes, Bloom County, Peanuts, Shoe, Hagar the Horrible, Popeye, and even in an imagined sense in Buz Sawyer, Prince Valiant, and The Phantom — but never so closely as in the image above. This is my dream of glory as a child! And likewise many friends and acquaintances of mine, particularly those who’ve lived lives of real or armchair swashbuckling from childhood onward.

The comic was drawn by William Steig, best-known today for Shrek. However, he drew a series of “Dreams of Glory” comics in the 1940s and 50s (I hope I have the dates correct) for various upscale magazines, primarily The New Yorker. Most if not all of the comics were published in a single volume in 1953.

I’ve updated this…

View original post 275 more words

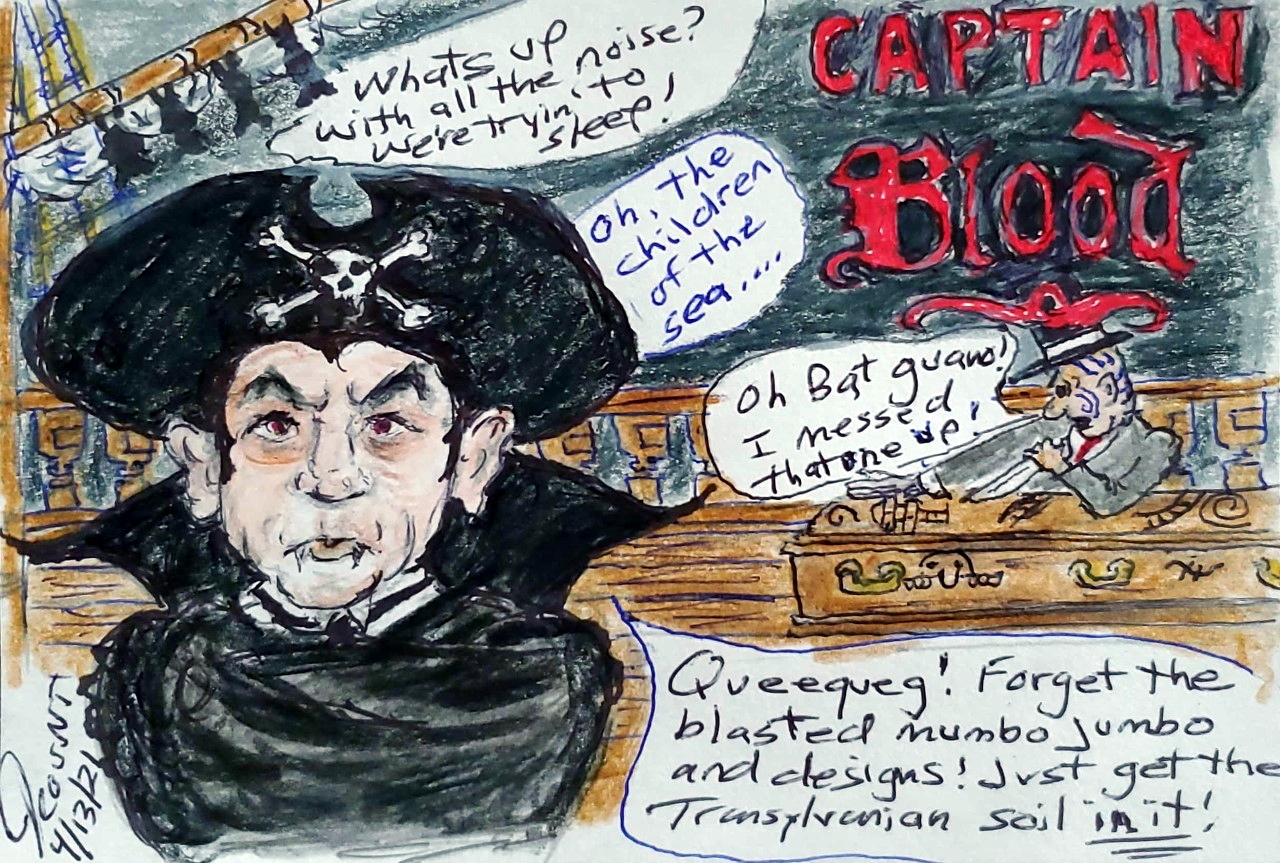

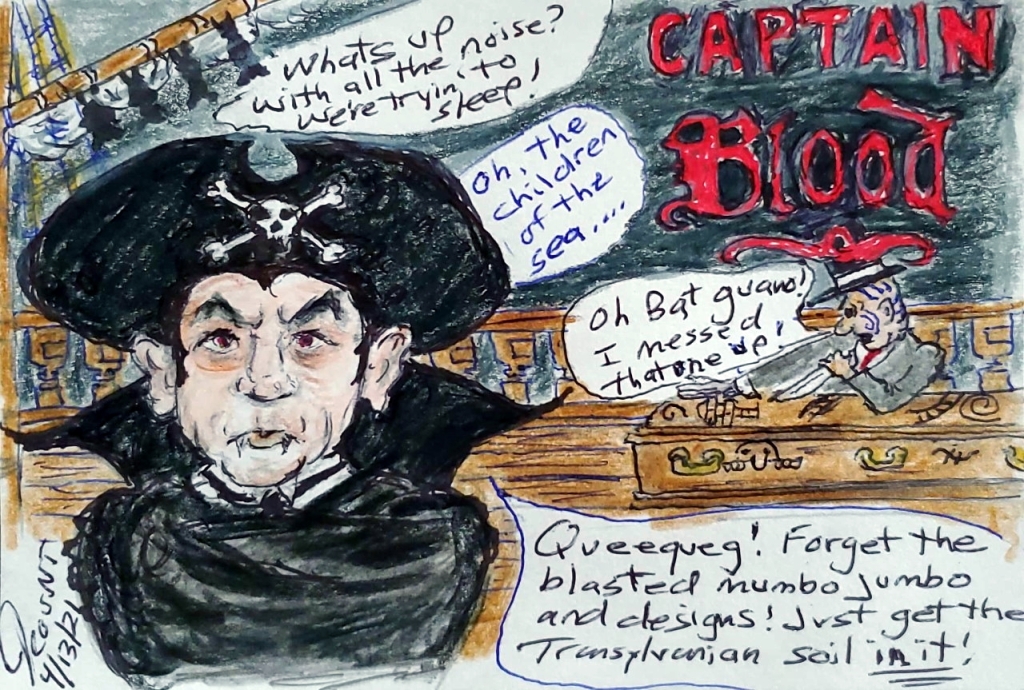

“Captain Blood” on Halloween!

A vampire — surely Lugosi himself! — riff on Captain Blood, with a Moby Dick reference no less, by friend and arms historian Jim McDougall. 🙂

Is the ship the Arabella, the Pequod, or the Demeter? 🙂

Comic copyright by Jim McDougall, 2021-2022. Blog copyright Benerson Little 2022. First posted October 17, 2021.

“The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow” by Howard Pyle

And indeed he was a picturesque — and picaresque! — fellow, the buccaneer! Howard Pyle’s painting of this romantic sea rover has influenced the imaginations of half a dozen generations of readers, writers, illustrators, costume designers, film-makers, and game designers. Currently on view at the Delaware Art Museum, the painting was one of four created for an article, “The Fate of a Treasure Town,” also by Pyle, published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1905.

In fact, the paintings accompanying the article are some of Pyle’s most famous buccaneer and pirate images. In addition to the picturesque buccaneer, there is “An Attack on a Galleon,” “Extorting Tribute from the Citizens” (used as the cover of The Buccaneer’s Realm, for what it’s worth), and “So the Treasure Was Divided.” Of the most famous paintings of his buccaneer, as opposed to pirate, series, only “Which Shall be Captain?” for “The Buccaneers” by Don C. Seitz, in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, January 1911, and “How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas,” Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899, are missing. (High resolution images are available on Wikimedia Commons.)

Pyle’s article opens with romantic tropical buccaneering scene-setting, then shifts in detail to the sack of Cartagena de Indias in 1697, a privately-funded French privateering expedition that was composed of hired ships and troops of the French navy and army, with a large body of French buccaneers and Caribbean militia in support. The Baron de Pointis, commander of the expedition, swindled the buccaneers out of their agreed share, so they returned and extored more treasure from the citizenry. Pyle’s painting, “Extorting Tribute from the Citizens,” shows buccaneers actively engaged in this pursuit. (On a side note, the painting was used for the dust jacket of The Buccaneer’s Realm, my second book.)

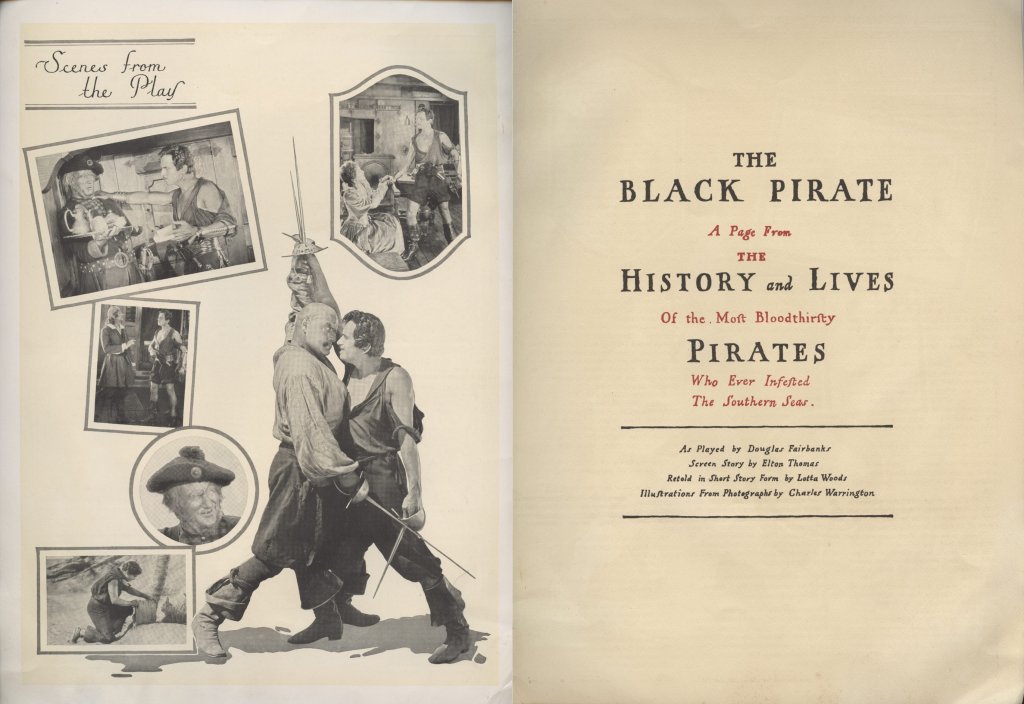

But few people have actually the read the article or even know about the sack of Cartagena de Indias, and it’s the images themselves that have caught our imagination. In particular, film-makers, illustrators, and Disney have borrowed heavily from the paintings: from The Black Pirate of Douglas Fairbanks and the Captain Blood of Michael Curtiz, to Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean attraction and films, to the sea rover art of Don Maitz, Pyle’s influence is impossible to deny.

From a historical standpoint, the paintings are far more evocative than accurate, although clearly Pyle attempted to get historical details correct. But this wasn’t easy. He had to interpret written descriptions and also — the bane of truth-seeking historians and researchers everywhere! — appeal to popular tropes as well. For popular works, some degree to catering to popular expectations is considered mandatory, or so I’ve been advised (and immediately resisted, bound by nature to do my best to keep within the limits of fact and fact-finding, at least as much as possible).

For Pyle, it was not the buccaneer or pirate’s sea roving escapades that made him appealing: “It is not because of his life adventures and daring that I admire this one of my favorite heroes; nor is it because of blowing winds nor blue ocean nor palmy islands which he knew so well; nor is it because of gold he spent nor treasure he hid. He was a man who knew his own mind and what he wanted.”

He conveyed this well with his picaresque — sorry, picturesque — buccaneer even if it appears that the young man evokes a purely romantic image of a sea roving adventurer rather than a real one.

Let’s take a quick look at his arms, accoutrements, and clothing and compare them to the historical. We’ll begin with his hat. Spotting the red ball tassels, we assume the hat is intended to evoke Spain — it’s the somewhat tropish hat of a Spanish flamenco dancer or mounted matador. Perhaps the buccaneer captured it, or, I think more likely, the buccaneer is in fact a Spaniard, a mestizo perhaps. We know that there were Spanish renegados among the buccaneers. Let’s keep this in mind as we look at the rest of him.

He’s wearing two gold earrings — small simple hoops. Most European-derived buccaneers did not wear earrings, with the occasional exceptions of the Dutch (single pearl, single ear) and fops (single pearl, single ear). However, all too often our impression of pirates is influenced by our ethnocentrism: some Africans, Native Americans, mulattos, and mestizos in the Americas did in fact wear earrings. Pyle probably added earrings as part of the expected pirate cliché, but to my mind, the earrings, considered historically, are more evidence that this buccaneer is a Spanish mestizo renegade, as is the perhaps fanciful bracelet on his wrist. His dark hair and olive skin — also “Spanish” clichés — are to me more evidence of his Hispano-American origin.

He has a red cloak over his shoulders, but would a buccaneer wear one? Probably not in the daytime, given the highs in the upper 80s and lows in the upper 70s year-round in Cartagena de Indias, although in some areas of the Caribbean cloaks, jackets, blankets, “ruggs,” &c were worn or used, typically at night. That said, a 1680s image, if not eyewitness then at least based on eyewitness descriptions does show a Spanish pirate or privateer with a cloak! More on this below.

Further, French priest and eyewitness Jean-Baptiste Labat described the admiral of the Armada de Barlovento in the Caribbean as wearing a cloak, but he was an old man and perhaps needed the cloak to keep his old bones warm at sea. And Spaniards wearing them are depicted in period images of New Spain, see the last image below for example. Perhaps, as with the Spaniard’s ruff which was often added historically as a satirical symbol — Spaniards no longer wore ruffs –, Pyle added the buccaneer’s cloak as a mere symbol of dress to indicate that the man is a Spaniard. This isn’t the first time Pyle put a cloak on a buccaneer: he also did so in his painting, “How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas,” Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899.

His “musket” is a bit of an anachronism: it is a Jaeger or Jaeger-type hunting rifle. Developed in the late 17th century in the region later to become known as Germany, there is no indication they were ever used by buccaneers. These Caribbean sea rovers used the long fusil boucanier, especially among the French, and various other muskets at times. However, there are instances of carbines (Sp. carabinas) in use on occasion at sea and ashore, and we will assume this is what Pyle meant to represent. His pistol could represent any number of sea pistols in use at the time, and is close to their common size. Its lock is indeterminate, but it hints of a Spanish Miquelet style.

His rapier, or possibly broadsword, is a shell-hilt, of what could be a Spanish-style doble concha, although the true cup-hilt (taza) was far more common. All or nearly all English, French, and Dutch buccaneers carried cutlasses, although there are documented indications of a few exceptions for smallswords and broadswords. However, the rapier — espada ropera — was still in common use in Spain, Portugal, and Spanish-governed parts of Italy at the time, not only among gentlemen (and most Spaniards considered themselves gentlemen!), but also among soldiers and almost surely among some seamen and artilleros. In fact, the eyewitness, or nearly so, image below of a Spanish privateer or pirate from the 1680s shows him wearing a Spanish rapier. Curved quillons were uncommon on Spanish swords of the era, although they did begin to show up on some at the end of the 17th century. Again, although for Pyle the rapier may have been a necessary trope, historically it would point the buccaneer being a Spaniard, Portuguese, Italian, or Corsican.

His sash is a bit wide, at least from what eyewitness images suggest, but his belt is correctly worn over it. The pouch or box on his right may be a cartouche box worn on a strap in a rather un-buccaneer style. His breeches, buttoned at the sides, are quite typical of those shown worn by Spaniards in the era, although Pyle may have depicted this style to evoke the swashbuckler or pirate as he did in other paintings, “I Had Met My Equal” for example.

And last, his sandals: most buccaneers, according to eyewitness descriptions and images, wore conventional shoes, or boucanier shoes made from skin pulled from the hocks of hogs (see here for details), or went barefoot, at least among the poorest sort. However, as noted not all buccaneers were English, French, or Dutch. Some were Spanish renegades, including Spanish Native Americans and mestizos, and we know that some of both groups wore sandals at the time.

The image below was drawn by a French engineer in the 1680s, almost certainly based on local eyewitness accounts of French pirates or privateers who attacked Nipe on Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti). There is no chance Pyle ever saw this image, yet his picturesque buccaneer evokes it well! The Spaniard is even wearing a cloak! Many Spanish pirates and privateers — most, some eyewitnesses noted — were men of color: Native Americans, mestizos, Africans, and mulattos. Is this what Pyle intended, a Spanish or mestizo renegade buccaneer? I can’t be entirely certain, but the evidence and my gut assure it is.

Bookends, Bookcovers, & More…

The painting has inspired a variety of objects and art, ranging from bookends to bookcovers to game miniatures. The bronze-clad bookend below, “Pirate’s Den” by Peter Manfredi (1930) for the Pompeian Bronze Co., is a three dimensional copy of Pyle’s painting. This example is one of two variants; the other has part of the background removed.

The Pompeian statuette bookend below, “Buccaneer” by Peter Manfredi (1930), was clearly inspired by Pyle’s painting. On the left is “Miss Pirate” by the same sculptor and year for Pompeian Bronze Co., Brooklyn.

In The Black Swan (20th Century-Fox, 1942), only loosely based on Rafael Sabatini’s novel of the same name, Tyrone Power’s costume is clearly based on, and probably an homage to, Pyle’s famous painting. The hat with tassels hanging from it, the cape, the sash, the rapier, are all clearly intended to evoke Pyle’s picturesque buccaneer.

The image has been used often on the covers of trade paper editions of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini. The one below is published by the Naval Institute Press. Pyle’s painting doesn’t evoke the urbane and sedulous Captain Peter Blood, but it does evoke the buccaneers he led. In fact, part of the novel takes place during the sack of Cartagena de Indias, although Sabatini moves the attack on the beautiful city up in time.

The painting inspired the cover of a mass market edition of Cup of Gold by John Steinbeck, a fictional, and quite literary, account of famed buccaneer Henry Morgan.

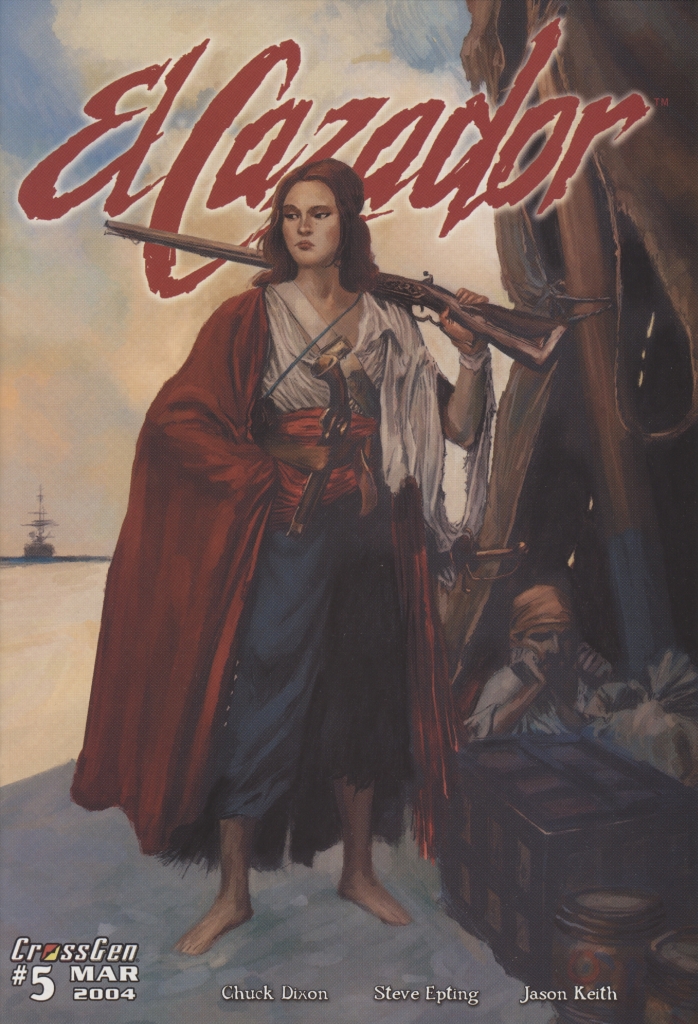

CrossGen published a series of six comic books 2003-2004 by Chuck Dixon, Steve Epting, and Frank D’Armata featuring a Spanish female pirate hunting captain, Donessa Cinzia Elena Marie Esperanza Diego-Luis Hidalgo (seriously!). Captured by buccaneers in 1687, she turns them into pirate hunters to seek out and destroy their pirate lord in return for the location of a great treasure. Commanding El Cazador, she is known by her English and French crew as Lady Sin and Captain Sin. She appears on the cover of Issue 5 (March 2004) in an homage to Pyle’s Picturesque Buccaneer. My many thanks to Antón Viejo Alonso for reminding me of this comic book cover!

The Naxos re-release of these film music classics by the Brandenburg Philharmonic Orchestra uses the picturesque buccaneer on the “album” cover, albeit reversed. Good music too!

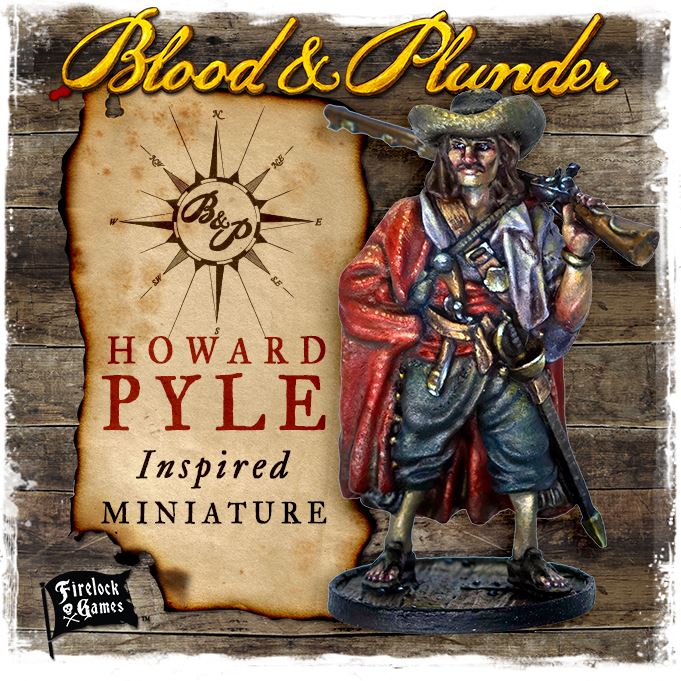

Firelock Games created a special edition figure as an homage to Howard Pyle for its popular (and quite historically accurate) Blood & Plunder tabletop wargame. (Full disclosure: I’ve done quite a bit of consulting for Firelock Games.)

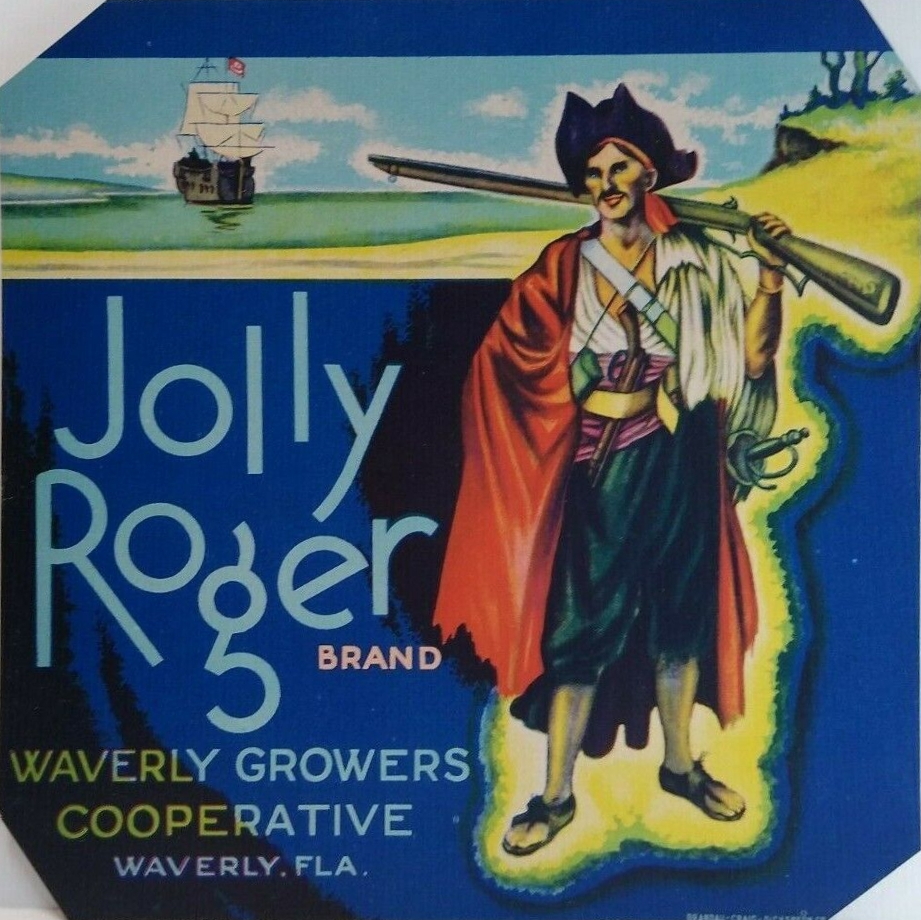

Even produce growers, or at least one of them, have appropriated the swashbuckling image…

Perhaps the most significant homage to Pyle’s painting came from another great illustrator: Norman Rockwell. But Rockwell’s buccaneer is no longer the youthful adventurer with a touch of arrogance, but a tired grizzled veteran with torn cloak and shirt, a sash of a different color, a hat that has long lost its tassels, and a leg lost to a broadside, yet who keeps sailing the Main with his buccaneer brethren even as he begins to long for home. There are a few anachronisms, as there always are in such paintings: his pistol is of a later era, as is the cutlass that has replaced his rapier, and his boots are entirely fanciful and unhistorical — pirates didn’t wear any such footwear. But I find no real fault with such details. As I said, these are evocative, not historical images.

But I do find fault with the home Rockwell has the buccaneer dream of, for it evokes Olde England as N. C. Wyeth might have painted it — perhaps even the Admiral Benbow Inn! — and not Spanish America. I imagine our Spanish renegade buccaneer, young and old, longing instead for a place along the Spanish Main: Campeche or Veracruz, Havana or Matanzas, Puerto Bello or Maracaibo. Or perhaps he’s even from Spain! But no matter: he has chosen to sail with the hated buccaneers, and might never see his home or family again. But let us remember that these are only paintings, only part of the story: we might fill and finish the buccaneer’s tale as we please.

Copyright Benerson Little 2022. First posted August 17, 2022. Last modified March 6, 2023.

Creating that Ship-at-Sea Sensation While Armchair Adventuring: Some Progressively Tongue-in-Cheek Suggestions

A practical, yet certainly tongue-in-cheek, post about creating a buccaneering sensory environment while reading Captain Blood in your armchair, playing Blood & Plunder or Oak & Iron or a buccaneer board game with your friends, watching The Sea Hawk or any other classic sea roving swashbuckler, playing a piratical video game (Monkey Island, AC Black Flag, and Sea of Thieves come to mind, or Skull & Bones when it’s released), or finally finishing that 1:48 scale model of a 17th century Spanish pirate hunting frigate (perhaps even the Cinco Llagas!) you started a quarter century ago…

Pine Tar & Cordage!

If there’s any single smell that evokes seaman’s “heart thrice walled with oak and brass”* during the golden age of sail, it’s pine tar. It was one of the principal naval stores, critical in the age of wooden ships. Unlike turpentine which was drained from pine tree trunks by notching them serially and collecting the sap, both in liquid form and as hard rosin (pine resin), then boiling it, pine tar was derived by stacking sap-rich pine wood from old growth trees in great heaps, burning it, and collecting the tar as it drained from the bottom. Pitch is simply pine tar further distilled to make it thicker. Pitch was used to seal the seams between planking after paying them with oakum, &c.

Pine tar was thinned with turpentine to preserve running rigging; in thicker consistency for marline; and even thicker for standing rigging. It was also used, often heavily thinned with turpentine and mixed with linseed oil or tallow, or both, for treating the planking on ships’ sides.

Its smell is, to those like me who love it, entrancing. Nothing evokes the old wooden ships like it does! But to those who hate it, those for whom organic smells cause them to recoil in nasal horror, it is akin to the combined smell of rotting road kill and hot roofing tar.

There are several excellent methods for bringing these scents about:

1. The simplest by far is to buy a tin of real pine tar–you can order it online–and open it, or better yet, pour a little bit into a small container and leave it uncovered. It doesn’t take much to fill a room with the smell. Sniff deeply from the container every quarter hour. Or dip your fingers in it and sniff them every so often–then wipe well unless you want your book or miniatures to smell like pine tar too.

2. Learn sail-making by making a ditty bag. You’ll need tarred marline, its smell will linger for months. Keep the bag nearby. When the marline eventually dries out, refresh it with a mixture of pine tar and turpentine.

3. Buy a ball of tarred marline, keep it in a plastic container so it doesn’t dry out over time, open it up as required for the salty tar smell. You’ll need it anyway for suggestion #2 above.

4. Bathe with pine tar soap. There are several on the market, Grandpa’s is highly recommended by many a tall ship sailor. Or just sniff the soap bar occasionally.

5. Treat your shoes with Huberd’s Shoe Grease, it’s made of pine tar and beeswax. Or just open a tin and sniff it periodically. And it really does work well waterproofing shoes, boots, gloves, and also cartouche boxes (for those of you who need to keep your powder dry).

6. Brew and drink Lapsang souchong tea–it smells, and even tastes (pleasantly, actually) of pine tar. Really, it’s much better than you might think, even if it’s anachronistic. It’s easy to find.

7. Hang a coil of marine grade Manila nearby, or better yet, several, or even better, hemp cordage if you can find it. Wet it for best effect. Or, the next time you’re by the seaside, soak it for a couple of days in the ocean, let dry, then hang and sniff as desired.

8. If you want to add more authentic smokiness, light a wood fire to augment the pine tar smell with that of the fire-hearth in the cook-room (NOT galley, that’s a later term). Place a pot of cornmeal (ideally coarse stone-ground cornmeal, but polenta, yellow grits, &c are close enough) and water on the fire to boil, add bacon fat or, better yet, unrefined manteca (pork lard), to season. Serve with boiled boucan (you’ll have to smoke your own boucan first, you can’t buy it at the market). Or, boil cornmeal dumplings, serve with unrefined manteca. When either or both are ready, dine like a buccaneer.

Be advised that, like most of these scents (or odors, depending on your sense of smell and olfactory triggers in your memory), your spouse or other significant other, unless a sailor or fisherperson, might not like them at all. You may hear about this, in fact. Nod with empathy, promise to keep the door closed.

Rum!

Pour a glass. Sniff. Drink. Repeat carefully. Don’t drive, neither ashore nor at sea, and don’t play with ANY firearms (a potentially fatal combination!) even unloaded, or sharp swords (you’ll stab your eye out for real, especially with a cutlass, or stick your foot to the floor/deck with a smallsword or rapier, the latter incident I’ve some experience with) while imbibing, nor afterward until the effects have passed!

I recommend dark molasses-ey rums: Pusser’s Gunpowder or just plain Pusser’s, Gosling’s, most any Navy rum, &c, or any amber or dark Jamaican or Bajan rum. I’m also partial to the Colombian Ron Viejo de Caldas with a pipe and tobacco (especially in a snow storm with thunder and electric blue lightning, of which there aren’t any in the Caribbean), and Smith & Cross, an authentic 18th to 19th century shipped-from-Jamaica-to-London style is also excellent. If you like a strong molasses taste, try Cruzan Blackstrap.

Lately I’ve become enamored of Privateer Navy Yard, a colonial New England style rum, and, for making punch, Plantation O.F.T.D and Ministry of Rum’s Hamilton 114. Also check out some of the strong pot-stilled, unfiltered, uncolored, “funky” white (often yellow, really) rums. We’re spoiled these days with the number of “funky” aka “hogo” rums these days, including white or yellow rums similar to 17th and 18th century rums, most of which were white or pale yellow and drunk very young. I highly recommend Hampden Estate Rum Fire Overproof. (“Hogo” derives from “Haut goût” or “high taste” and denotes a strong molasses and other raw taste; in meat it indicates gaminess.)

If you’re a modern Cuban-American pirate, it’s going to be the original Cuban Havana Club (not the Puerto Rican stuff although I’ve nothing against it per se) and real Cuban cigars, or so I’ve been told by a modern Cuban-American corsario who introduced me to the combination. That said, it was the wife of a Hungarian who first introduced me to Cuban cigars, she’d smuggled (i.e. forgotten to declare, or so she said, to US Customs) them out of Hungary back in the days of the Iron Curtain.

You might also try a 17th-18th century rum punch. The classic modern recipe is one of sour, two of sweet, three of strong, and four of weak, with a bit of grated nutmeg (or even allspice). Translated to the 17th century, this means one part key lime juice (preferred, although you may substitute orange or even pineapple juice), two parts muscovado sugar, three parts rum, and four parts water. Nutmeg was also commonly used in the 17th century. (See the foot of this page for notes on acquiring muscovado and key limes.)

If you plan on serving punch in a bowl, Charles H. Baker Jr. in his a famous drink book The Gentleman’s Companion: Being an Exotic Drinking Book… (1946) suggests chilling all ingredients first, and placing a large block of ice at the center of bowl. Long gone are the days of ice trucks delivering blocks of ice to be chipped away in the ice box with an ice pick, but instead you can make a large block of ice by using a food storage container as a mold.

Tobacco!

Foremost, don’t smoke. And if you do, let it be only an occasional pipe or tobacco. And smoke outside — if you own your residence it will have better resale value, and your spouse or significant other might not murder you.

If you choose to smoke a pipe, try a high quality clay replica (a churchwarden is an excellent choice for you gentleman and lady buccaneers, but shorter pipes were more common shipboard), fill it with bosun’s rum twist (often called sweet rum twist), Sweet Virginia (Sutliff makes one), or Navy flake, and puff away. That said, I’ve been reliably informed that the early Oronoko (Verina, Sacerdotes, &c) and related Virginia tobaccos of the era were probably more like modern mild burleys.

Add an authentic replica of a seventeenth century pipe tamper if you like — a dolphin (aka dolphin fish, classical dolphin, mahi-mahi) or something bawdy, both of which were common along with other designs. (See Bucklecastings online for some.)

Or, smoke a cigar. Yes, cigars were popular in the 17th century Caribbean. Pretty much everyone smoked them to some degree, although pipes were more popular among the English, French, and Dutch. Cigars far outnumbered pipes among the Spanish, Portuguese, Africans, and, at least in the Caribbean and environs, Native Americans, and were smoked by women as well (as were pipes, by the way, among other nationalities), especially by Spanish women in the Americas. Check this out: Of Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar Smoking Women.

WARNING! Keep your pipe or cigar away from various flammable mixtures of pine tar, turpentine, beeswax, and linseed oil! Especially if you’ve been drinking rum!

WARNING! Keep your pipe or cigar away from your blackpowder, if any (see below), too! Blackpowder isn’t quite as sensitive to candle or common match flame as Hollywood depicts it, but a tobacco ember might still set it off. Put another way, it might take a dozen common wooden matches to ignite a blackpowder train — or it might take only one! And the flame from even a small amount of blackpowder can burn you to the bone! (Blackpowder, by the way, doesn’t explode, it deflagrates, if you want to get technical. It doesn’t burn as fast as true explosives.)

You can add a pipe bowl cover to your pipe for authenticity and, as was the case even three centuries ago aboard ship, for safety. It’s useful also when stalking wild cattle or feral swine on tinderbox arid coasts and desert islands. I recall my seafaring adventurer father using one when my brother and I would go hunting with him when we were in our early teens.

While smoking your pipe, take a break, tend your geraniums, and randomly shout, ideally from a window at passersby, “Quo, quo, scelesti, ruitis?” If you don’t get the allusion, shame on you! Go back to your armchair and do some more reading. 🙂

Blackpowder!

I’ve had my doubts about including this suggestion, given the large number of fools with firearms in the US these days. However, given that in my experience there are far fewer fools with blackpowder arms, I’ll go ahead.

WARNING! NOT NOT NOT FOR NOVICES OR AMATEURS! THIS IS NO JOKE! UNLESS YOU REALLY KNOW WHAT YOU’RE DOING, DON’T!!!

TRIPLE-CHECK that the barrel of your flintlock musket or pistol is UNLOADED. Prime (but do NOT load), point in a SAFE direction, bring to full cock, and squeeze the trigger — and thereby, assuming your flint is sharp and tight in the cock, fill the room you’re in with just enough smoke to bring your spouse or significant other down upon your ears after any nearby smoke alarms go off. Or maybe do this outside instead and hope your neighbors don’t call the police on you, which they probably will (and probably should, just in case) for discharging a firearm within city limits. Remember what I said about fools and firearms…

Breathe deeply of this broadsides and boarding actions smell. As an archaeologist at the Middelaldercentret in Nykøbing Falster, Denmark put it to me (we were testing firepots and an iron breech-loading swivel gun for a TV show), “There’s no one who doesn’t like the smell of blackpowder!”

If you like, afterward clash a couple of swords together afterward to suggest a boarding action. Prefer fencing swords rather than real cutlasses or functional replicas in order to avoid nicking sharp blades unnecessarily. If you’re going to nick edges, let it be in a real boarding action of which there really aren’t any of the age of sail sort anymore. Cue Jimmy Buffett…

WARNING! Don’t mix with rum drinking! Or any drinking! Or any other substance that impairs your judgment!

Sound Effects!

Put on music or videos of surf, preferably with seagulls in the background.

Or listen to a video (YouTube surely has some) of tall ship sounds–the sea, creaking rigging, seagulls.

Ignore this if you live by the sea or on a boat or ship (lubbers take note: a boat and a ship are not the same thing). If you live near a dump you might hear seagulls. Ignore the smell or pretend it’s the ship’s bilge.

You can always put on a CD of sea shanties, the bawdier the better in most cases, but accept the fact none are 17th or 18th century, but 19th & 20th century and therefore anachronistic. Or, put on a CD of John Playford’s popular 17th century tunes, there are at least two good compilations available. (Or stream them, I know, we’re well into the 21st century…)

If it’s Spanish pirating you want to evoke, try La Bamba: Sones Jarochos from Veracruz sung by José Gutiérrez & Los Hermanos Ochoa (a Smithsonian release). La Bamba was reportedly composed in the aftermath of the sack of Veracruz in 1683, lampooning the bombast of defenders who did nothing to stop the pirates — but claimed they would. Or, if it’s gentlemanly Spanish pirating you want to evoke, try Fantasía para un Gentilhombre by Joaquín Rodrigo, it has elements of Gaspar Sanz’s 17th century guitar compositions; or just sample some of Sanz’s music instead. Navigating Foreign Waters: Spanish Baroque Music & Mexican Folk Music is also an excellent choice.

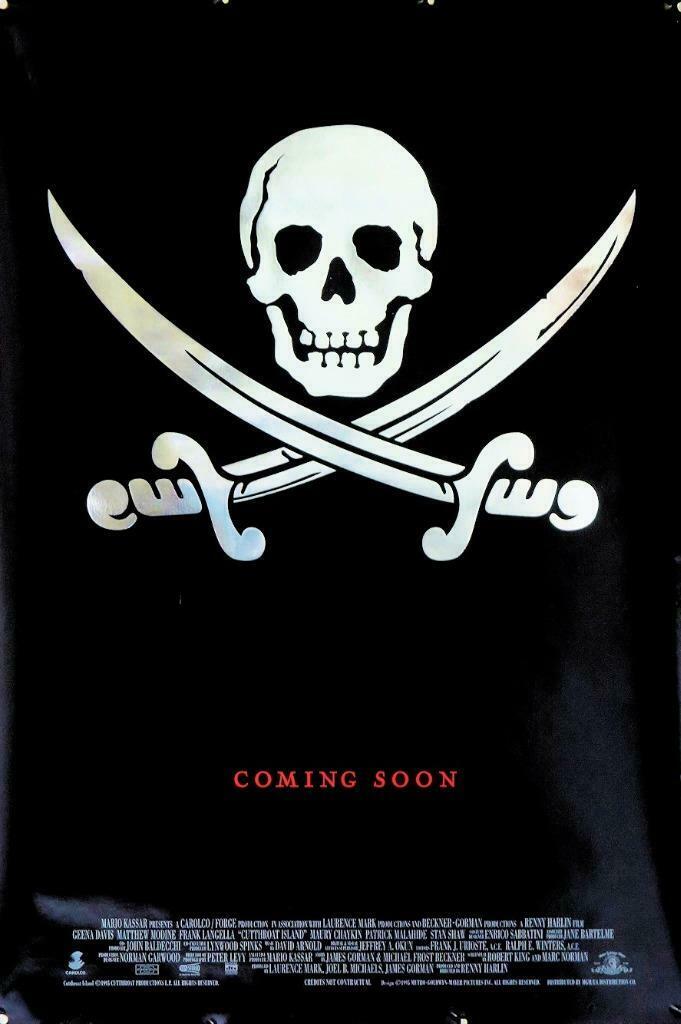

But if it’s Hollywood pirating you want to evoke, put on Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s score for Captain Blood or The Sea Hawk, Alfred Newman’s for The Black Swan, Franz Waxman’s for Anne of the Indies, Max Steiner’s for The Adventures of Don Juan (I know, Don Juan isn’t a pirate film or even a seafaring one but the score was used in The Goonies aboard the pirate galleon), John Debney’s for Cutthroat Island, or, one of my favorites, the Chieftains’ score for the best version of Treasure Island ever filmed.

Hang a ship’s bell nearby, ring it loudly occasionally, ideally with the correct number on the half hour, remembering to ring in pairs: ding-ding, ding-ding, ding, &c. Unless you’re a complete fool, avoid doing so if your spouse or significant other has a migraine.

Note that sound effects are unnecessary if you’re just watching a movie…

That Salty Sea Smell!

It’s almost impossible to imitate, so go live by the sea if you can. Upside: the smell and sound of the sea. Downside: everything rusts, including your car. Failing this, keep a bottle of seawater handy, open it occasionally, and sniff. If that doesn’t work, attempt to reproduce that special salty sea smell with water, salt, and a few dead guppies.

Pitching, Sending, Rolling, & Yawing…

There’s really not much you can do to emulate the feel of a ship underfoot except to go to sea or get drunk or carsick. Best substitute: a hammock. Try not to fall asleep in it after drinking two rum punches. If you plan on inviting your significant other aboard the hammock, whether to recreate life aboard a man-o’-war in harbor or on a desert isle à la Robinson Crusoe, make sure it will hold both of you up! In other words, if you hang your hammock on an isle or cay, make sure your weight won’t pull one or both small trees over onto you. Experientia docet…

The Ship’s Head, Chamber Pots, Pissdales, & the Bilge!

Pretend you’re a buccaneer quartermaster or captain and use a bucket or chamber pot to relieve yourself because you’ve got too much status to use the ship’s head or one of the pissdales (if even there are any along the gun’l), or you’re too lazy to piss in the bilge where you shouldn’t anyway (the ammonia stench from this could actually choke seamen out at times). Pretend your spouse is your personal servant (yes, some buccaneers had indentured servants as their personal servants, and even naval officers often went to sea with servants, mustering many as seamen and taking part of their pay, a common practice of dubious legality) and ask her or him to empty said relief. Stand by for a break-up. Or simply for the contents to be emptied on your head. Personally I recommend passing on this simulation, but to each his, her, or their own…

More Effects of Sight and Sound: Parrots!

Get a parrot, name it Pol (it’s where the name Polly comes from, you can thank Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe), teach it to shout “Pieces-of-Eight! Pieces-of-Eight!” over and over (but this’s from Stevenson’s Treasure Island). Don’t listen to anyone who tells you parrots are just a fictional pirate trope — some pirate tropes actually have a great deal of legitimacy, particularly this one. Don’t believe me? Check this out: Of Pirates & Parrots (& Monkeys, Too).

However, be prepared for to spend big bucks to acquire and maintain a parrot, and also for guilt trips when the parrot won’t shut the hell up and you stuff it in the closet for a couple hours for some relief. Also, the damn bird will probably outlive you, so make sure to include it in your last will and testament. Leave it to someone who’ll take good care of it. Extra points if giving it to this person will also satisfy your need for petty personal revenge. Warning: acquiring a parrot is a serious undertaking! Best substitute? House-sit for a few days, parrot included.

And Still More: Monkeys!

Get a capuchin (monkey, not monk), put it in a diaper, name it “Captain,” and let it roam free and destroy your home. Or maybe not: primates shouldn’t be kept as pets, although some members of Homo sapiens — a primate species — inexplicably, even unconscionably, thrive on it (both keeping monkeys or other primates, including humans figuratively, as pets, and being kept as pets, that is).

Drawback: monkeys, not to mention many politicians and Internet windbags these days, often fling their turds at humans and can be quite obstreperous when it comes time to correct or prevent their bad behavior. (I’ll forgive monkeys but not politicians, pundits, or “influencers” aka product shills.) For what it’s worth, monkeys are another pirate trope with a great deal of maritime legitimacy. See the link above.

And If You’re Really Bold…

Just stuff the book you’re reading or the game you’re playing into your sea bag or sea chest, find a tall ship in the offing, and join her (its) crew!

Notes on Muscovado and Key Limes

Key limes are available in many groceries these days, including Walmart’s produce sections. Often the limes are listed as Mexican, given their usual origin, and they’re also known as West Indian limes. You’ll know them by their size, a third that of conventional limes.

For muscovado sugar, I recommend buying it in bulk from Amazon, it’s by far the best value, ten one-pound boxes, Billington’s Natural Dark Brown Molasses Sugar, or for a lighter taste, Billington’s Light Muscovado. (Colonial sugar plantations produced both dark muscovado and a lighter “clayed” sugar — in fact, sugar production was responsible for the majority of African slavery in the New World.) Much smaller quantities cost almost as much as ten pounds in bulk. Billington’s also makes a Dark Muscovado but it’s hard to find in bulk in the US and is quite pricey in smaller quantities and in any case I can’t tell much difference between it and their dark brown molasses sugar — the latter tastes, looks, and cooks like muscovado, except that it has more molasses than the average muscovado, and has less of a floral flavor; most “experts” regard the dark molasses sugar as a form of muscovado. India Tree also makes a muscovado sugar, but prices vary widely; some groceries sell it for around six or seven dollars a pound.

Use dark or light also for baking cookies, frying plantains with butter, making hot buttered rum (use Cruzan’s Blackstrap!), on oatmeal, &c, and for any other brown sugar need. This is the real stuff! You can also use panela, piloncillo, and similar “brick” or “cone” cane sugars to substitute for muscovado, they’re quite similar to 17th century sugars — in fact, they’re produced in much the same way and are generally considered as forms of muscovado. Dark muscovado is marketed in some areas of the world as Barbados sugar, although most today comes from Mauritius and the Philippines.

* Robert Herrick in “A Country-Life: To His Brother Mr. Tho. Herrick” (Hesperides, 1648) quoting Horace, Odes I.3 in translation.

Copyright Benerson Little 2022. First posted July 6, 2022. Last updated March 28, 2024.

Captain Blood, Not Jack Sparrow: The Real Origin of Disney’s Wicked Wench Pirate Ship

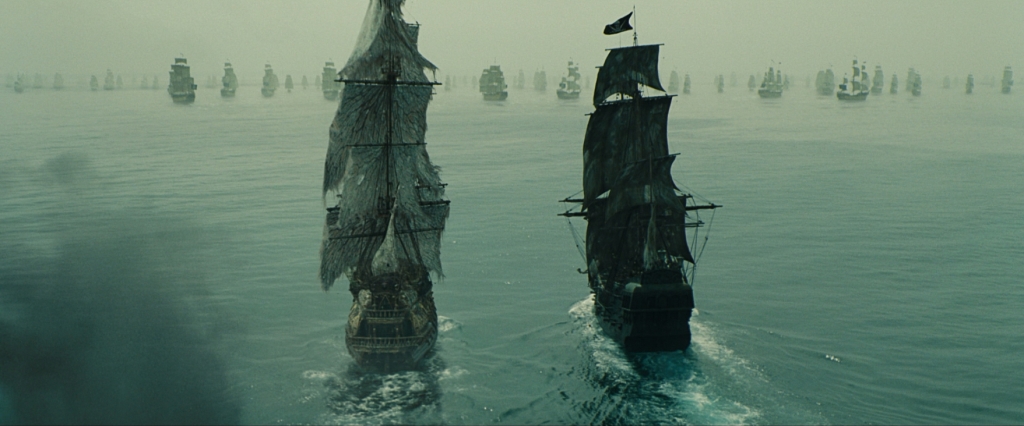

It’s an epic image, one that anyone who’s ever cruised through the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction at one of the Disney theme parks is familiar with: a pirate ship cannonading — “firing its guns at” or “engaging” in sea parlance — a Spanish fort.

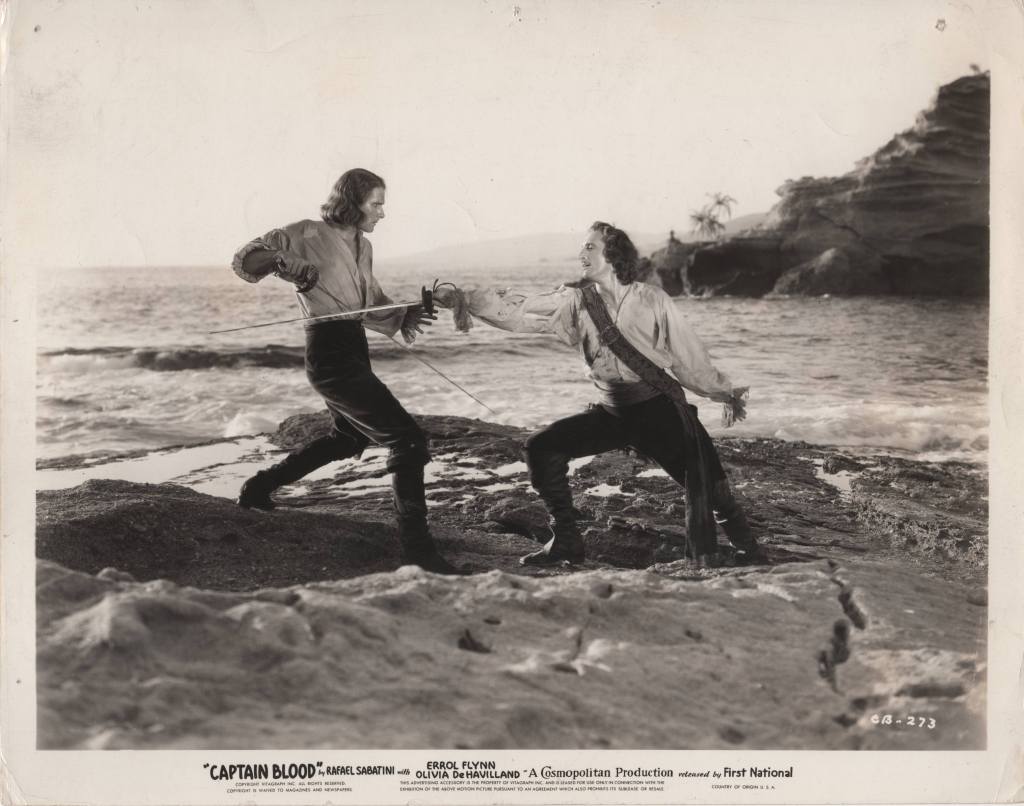

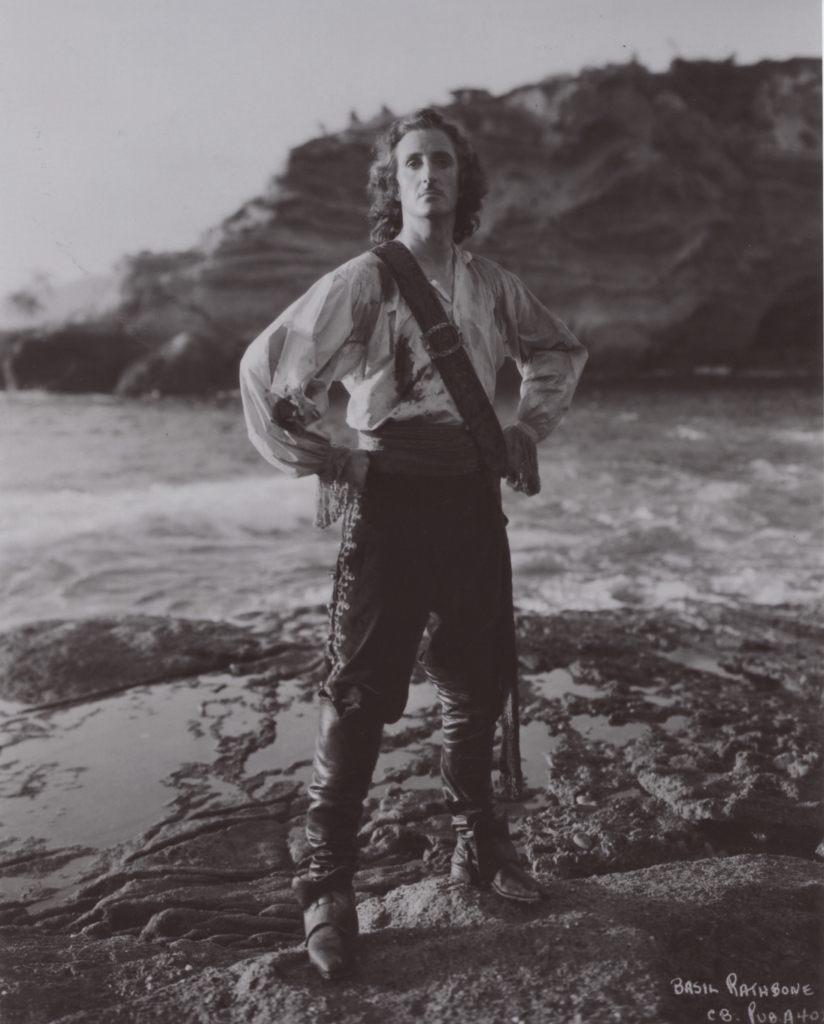

But the image-in-motion long predates the Disney attraction. In fact, as I’ll demonstrate shortly, the entire scene was lifted directly from Rafael Sabatini’s famous novel, Captain Blood: His Odyssey and especially from the 1935 film version starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone. And the Wicked Wench pirate ship of the attraction was more than simply inspired by the Cinco Llagas / Arabella, as the ship in the novel and film was named: it was copied from it!

Originally the attraction depicted buccaneers in the second half of the 17th century attacking and sacking a Spanish town on the Main. “IN THE CROSS FIRE of cannonades between pirate ship and Caribbean port,” begins the caption of the 1968 Disney publicity still of the Wicked Wench shown above. It continues with “this crew of Disneyland adventurers sail through Pirates of the Caribbean as grape shot and cannonballs land around them. The pirate captain on his bridge gives the signal for an eight gun salute. The scene of one of ten action-packed segments in the thoroughly realistic re-creation of buccaneer days.” For now I’ll pass on correcting Disney’s descriptive language, as some readers might misconstrue such revisions as nautical pedantry.

However, in spite of the obvious historical basis for the ride’s inspiration, according to Disney’s modern Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise “canon” the Wicked Wench was instead the ship that would become the Black Pearl commanded by Jack Sparrow et al, more or less, post-buccaneer era. Not a buccaneer ship, in other words, but a later ship turned to pirate ship as would fly the Jolly Roger. This, of course, is nothing more than mere revisionism for the sake of marketing the ride on the coattails of the film series, and any “canon” (as in nearly all franchises) is nothing more than the result of a series of screenwriters trying to write popular scripts, and fans subsequently trying to make rabid sense of their details and many loose ends.

Myself, I much prefer the original orientation of the attraction, liberties taken with real buccaneer history notwithstanding. That said, comic ride though it may be (and one that I thoroughly enjoy), it does get some things right, including torture, pillage, and burning, not to mention the original implication of some scenes now altered from their original. We have, in fact, two versions of piracy in our culture: factual history and popular myth, the latter often overwhelming the former.

And now for the evidence that the Wicked Wench is really the Cinco Llagas / Arabella!

The Scene of Ship Attacking Fort Was Inspired by & Lifted Largely From the 1935 Film

One need only to watch the 1935 Captain Blood to confirm this. The only difference between the two is that the roles are reversed: rather than a Spanish pirate attacking the principal town of an English colony in the late 17th century as in the Rafael Sabatini novel and the film based on it, buccaneers in the attraction attack a Spanish town, as they often successfully did — and far, far more often than Spanish pirates did against English, French, and Dutch colonies.

In fact, in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Black Pearl there is an homage to the pirate attack in the 1935 film version of Captain Blood: some of the shots of locals running for cover are quite similar to those in Captain Blood.

For more details on the ship-versus-Spanish fort trope, see “The Iconic “Spanish” Fort: Only a Spanish Galleon Says “Pirates” Better!“

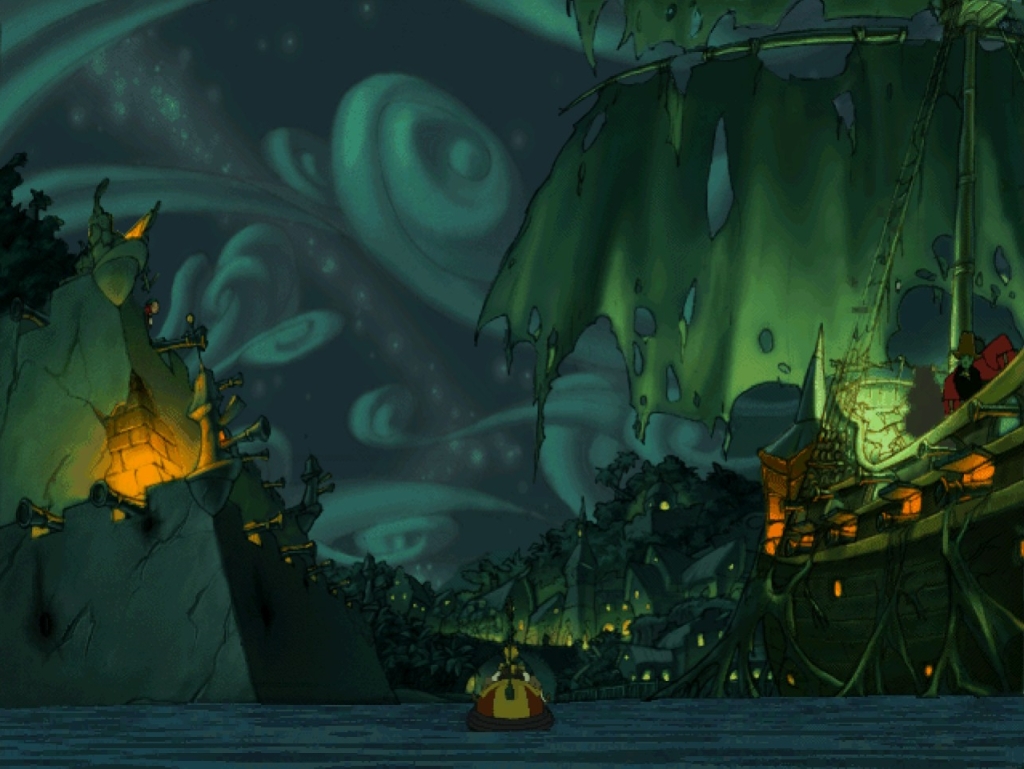

The battle depicted in the Disney ride, and by derivation the one in Captain Blood, was given an homage in The Curse of Monkey Island (LucasArts, 1997).

The Wicked Wench is Red Like the Cinco Llagas / Arabella of the Novel

According to Rafael Sabatini, who clearly emphasized the sanguinary nature of buccaneering via the hero’s name and other thematic elements, the color of Peter Blood’s pirate ship was red. However, red was not an exceptionally common color of ships at the time. Red paint was typically used for the bulwarks (the inner “walls”), gun carriages, and often some fittings of men-of-war, and some other ships as well, at the time, and the upper works (the upper outside of the hull) and sterns of some ships were occasionally painted red — but never the entire hull. However, the application of pine tar, tallow, and linseed oil could lend a reddish hue to hull planking (particularly to those ships built of various “mahoganies” in the Americas), but this would not cause a ship to be referred to as red. (Far more details on the possible appearance of the Cinco Llagas / Arabella are forthcoming in Treasure Light Press’s annotated Captain Blood.)

And the Wicked Wench? A red ship, of course!

The Profiles of the Wicked Wench and the Cinco Llagas / Arabella are Too Similar to be Coincidental

Indeed! The similarity is obvious when comparing the images below. Even the scrollwork on the stern upper works is almost identical (see the image above and also at the end of this section). Disney did make some alterations to suit the attraction, including reducing the ship from two decks to one, and, of course, making it small enough to fit in the attraction.

And Then There’s the Names of the Ships…

After its capture by a handful of renegade rebels-convict led by Dr. Peter Blood, the Cinco Llagas was renamed the Arabella after the woman Blood loved but thought he could never have. Arabella Bishop, although independent, strong-willed, and anything but swooning (or languishingly voluptuous!), was still a lady in manners and mores, unlikely to (sadly!) run away to sea in men’s clothes with Peter Blood. One can easily see a tongue-in-cheek homage to Arabella and the Arabella in the renaming of the Spanish frigate as the Wicked Wench, and even in the “Woman in Red” in the old Bride Auction scene on the attraction.

Likewise the captain of the Wicked Wench as an inverted homage: no clean-shaven gentleman buccaneer he, unlike Captain Peter Blood, but bearded and beribboned like Blackbeard the Pirate and bellowing in G-rated curses like Robert Newton or Peter Ustinov in their piratical film roles. That is, before Hector Barbossa took his place to align with the film franchise. (N.B. Blackbeard was not a buccaneer but a later black flag pirate, and although most buccaneers appeared to have been clean-shaven, some French boucaniers, and therefore buccaneers, did wear beards.)

For more details on “The Woman in Red,” now “Redd the Pirate,” (and in any case, an anthropomorphism of the ship by both), see “The Women in Red: The Evolution of a Pirate Trope.” For more details on the black flag — the so-called Rackham flag with skull and crossed cutlasses — flown by the Wicked Wench, see “The Fanciful, Mythical “Calico Jack Rackham” Pirate Flag.” Note that on the Disney LP featuring a narrated soundtrack of the ride, the Wicked Wench is referred to as the Black Mariah, the name of the ship in “Donald Finds Pirate Gold!” Perhaps Wicked Wench was suitable on the stern but not in narration at the time on an LP likely to be listened to mostly by children?

So, Was the Wicked Wench Really the Arabella?

Only Disney knows — and only Disney can answer how the Arabella, sunk among the cays just off Port Royal, Jamaica in 1689 while defending the town from French attack, came to be raised, refitted, and ended up again in buccaneer, then pirate, hands… 🙂

And the Black Pearl?

If you’re looking for the real original inspiration for the Black Pearl, discard any notion of it having been the Wicked Wench — this is probably just “canon after the fact.” Convenient revisionism for the sake of marketing, in other words. Sparrow’s famous ship is more likely inspired ultimately by Tom Leach’s 40-gun Black Swan, from Sabatini’s novel of the same title. Or at the very least it corresponds closely to Sabatini’s description of the ship, including its black hull. Even the un-authorized plastic model of Sparrow’s Black Pearl is sold under the name of the Black Swan. Are there similarities between the Wicked Wench and the Black Pearl? Of course there are. Clearly the set designers took a look at the Wicked Wench, but it is much closer to the Arabella. (By the way, the duel in The Black Swan is described here.)

And for you budding “nautical pedants” out there, here’s the correction to the Disney text quoted above: “this crew of Disneyland adventurers [an acceptable term: French buccaneers aka flibustiers were often referred to as adventurers] sail through Pirates of the Caribbean as grape shot [this form of small shot was in its early development and generally not known by this name at this time] and cannonballs [more correctly, round shot] land [splash] around them. The pirate captain on his bridge [quarterdeck, not bridge] gives the signal for an eight gun salute [a correct humorous euphemism for a broadside]. The scene of one of ten action-packed segments in the thoroughly [and humorous] realistic re-creation of buccaneer days [a statement more correct than it might appear at first]…”

Post Script: The Wicked Wench is Not the Only Disney Pirate Ship Inspired By an Errol Flynn Film…

Disney’s Jolly Roger, from the animated version of Peter Pan (1953), bears a striking resemblance to the Albatross from The Sea Hawk (1940, directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Errol Flynn). 🙂

Copyright Benerson Little 2022-2024. First posted June 22, 2022. Last updated February 9, 2024.

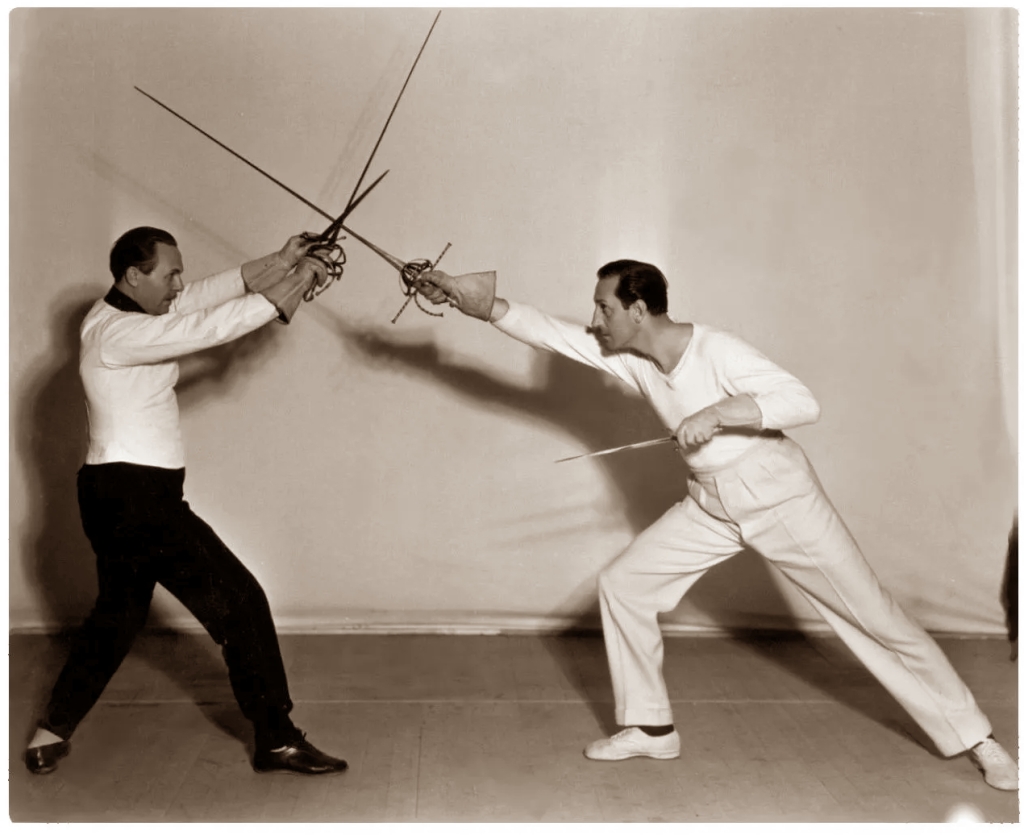

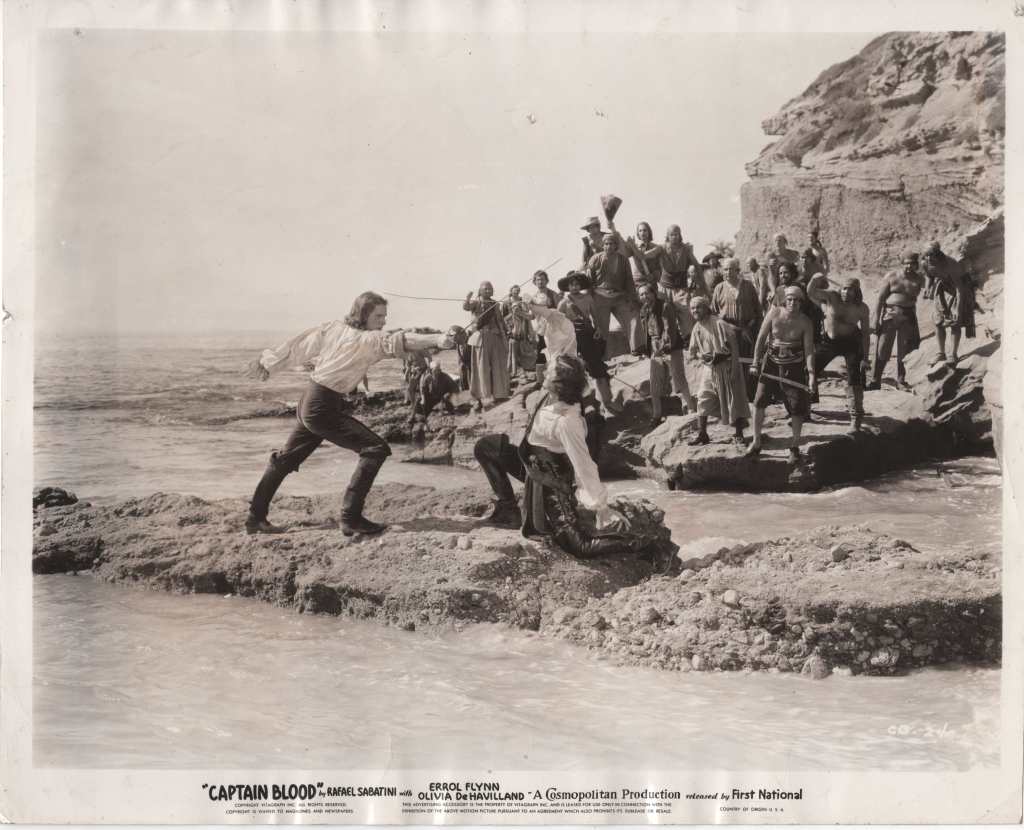

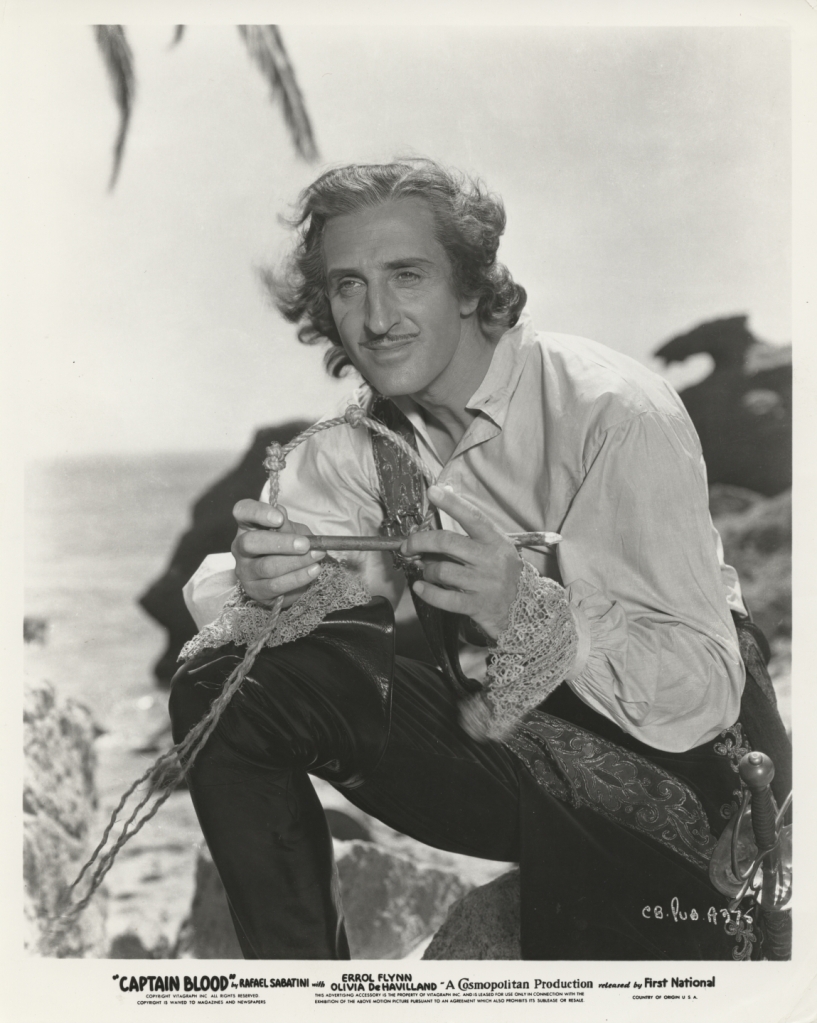

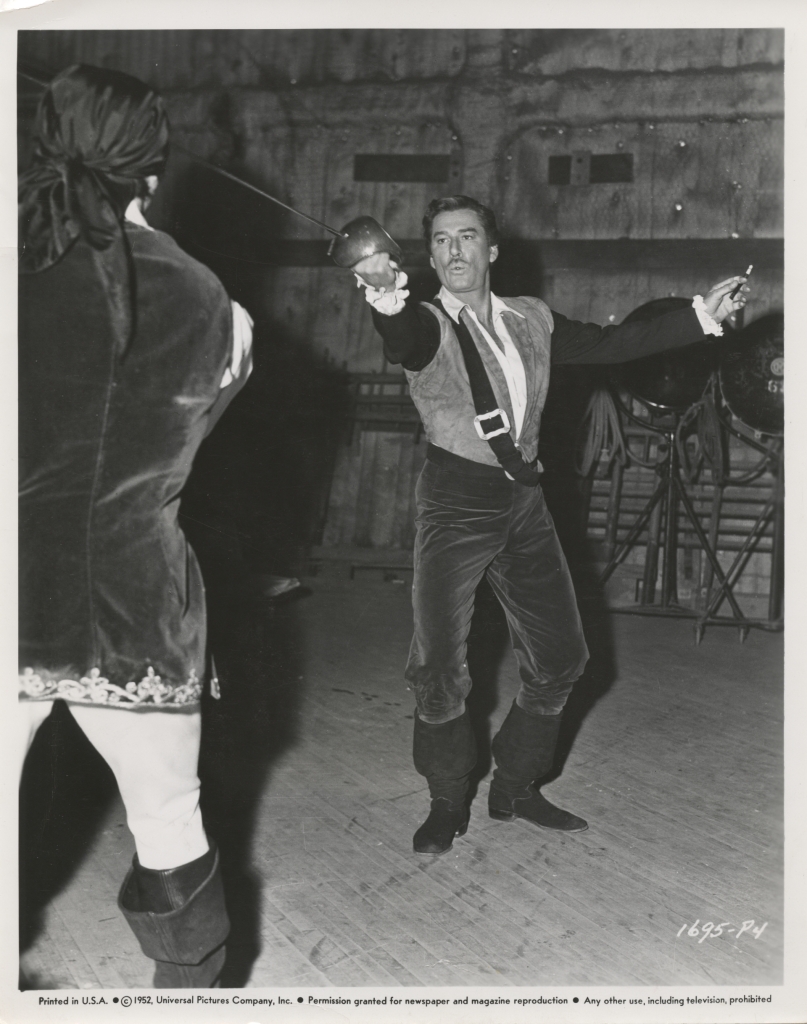

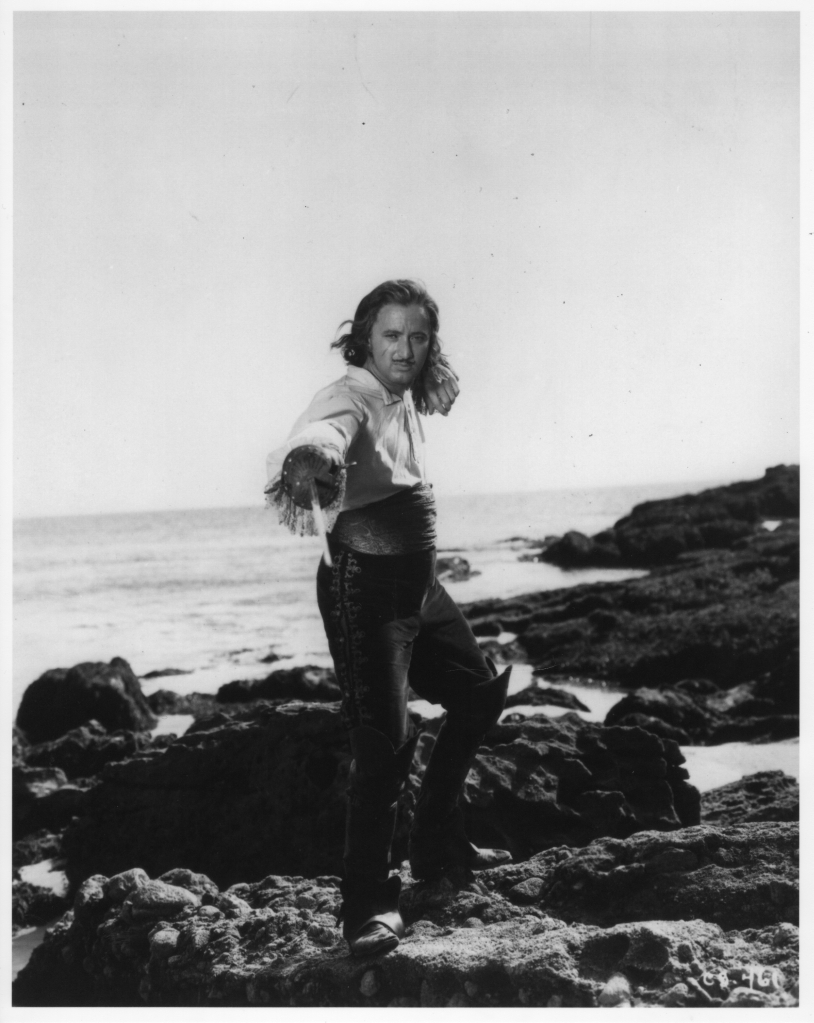

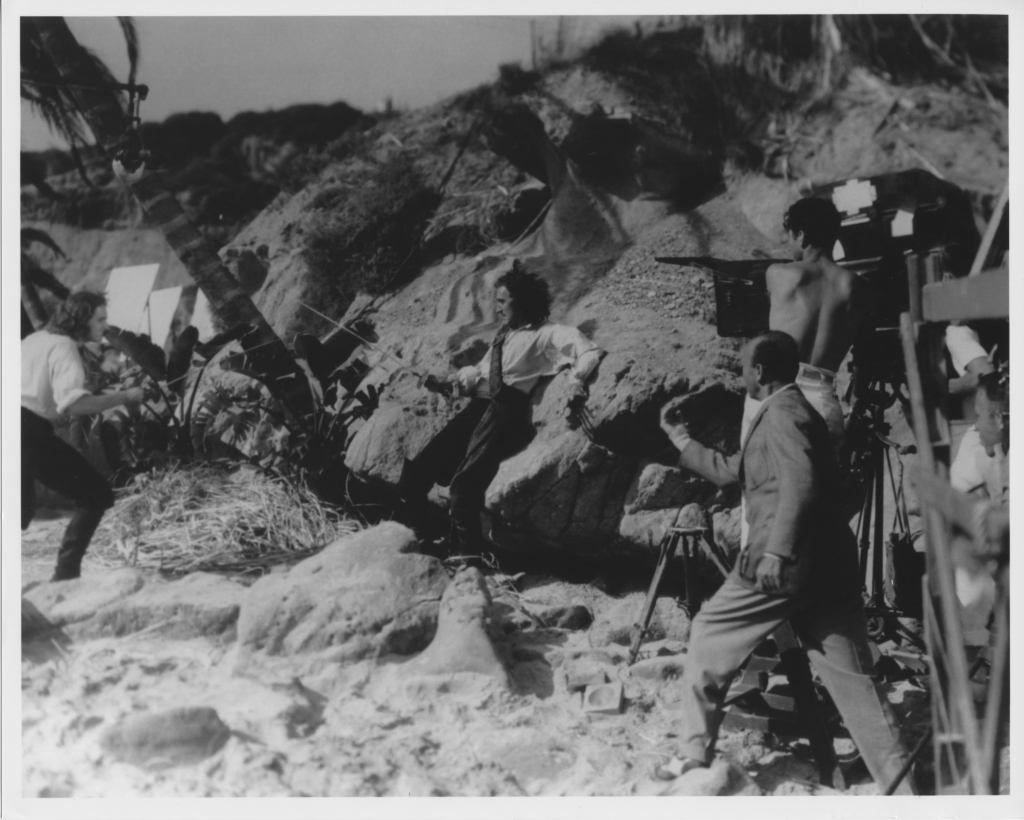

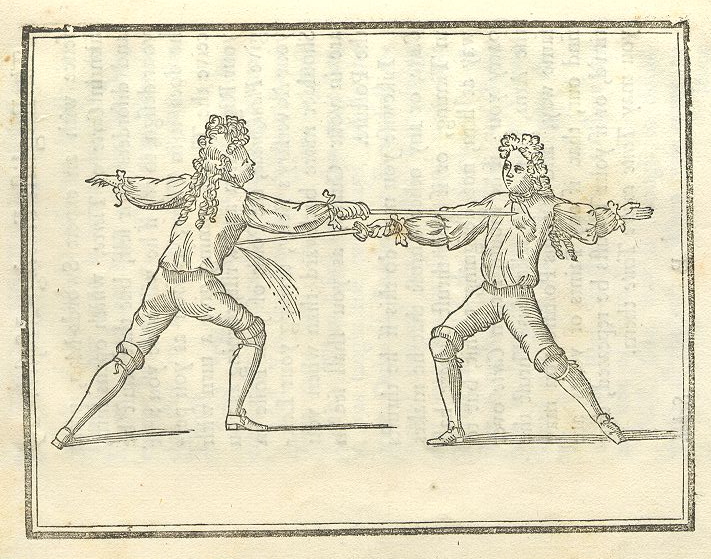

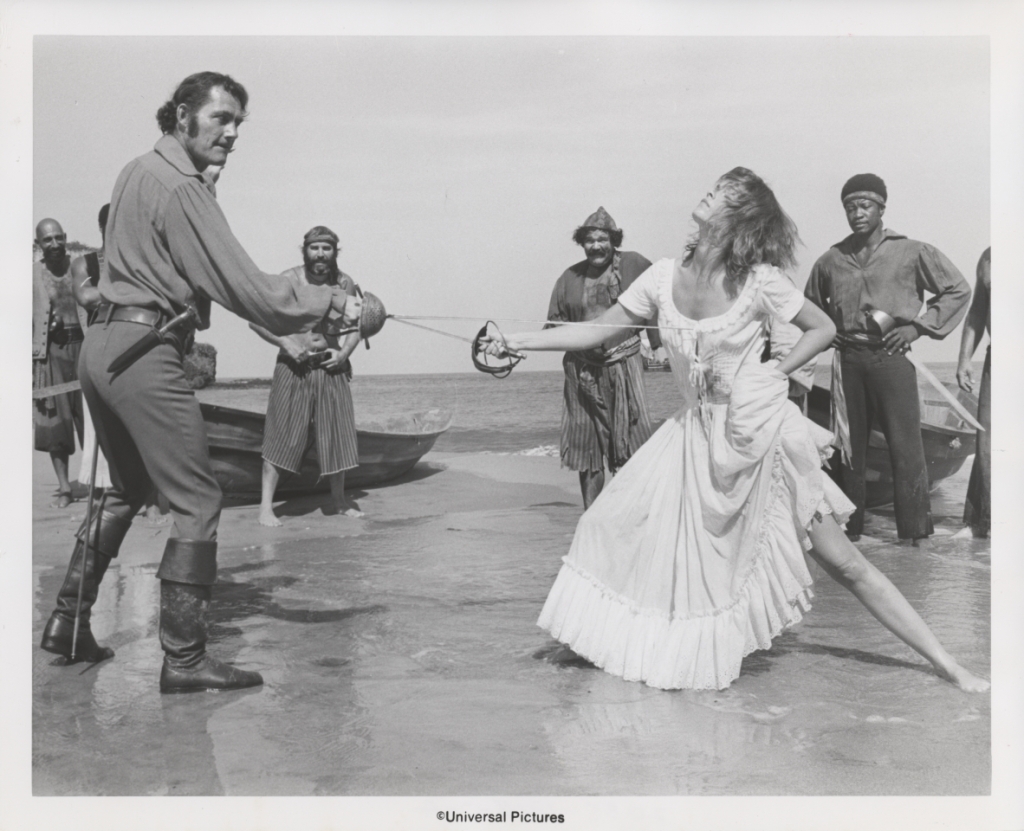

The Duel on the Beach, Part IV: Flynn versus Rathbone in Captain Blood!

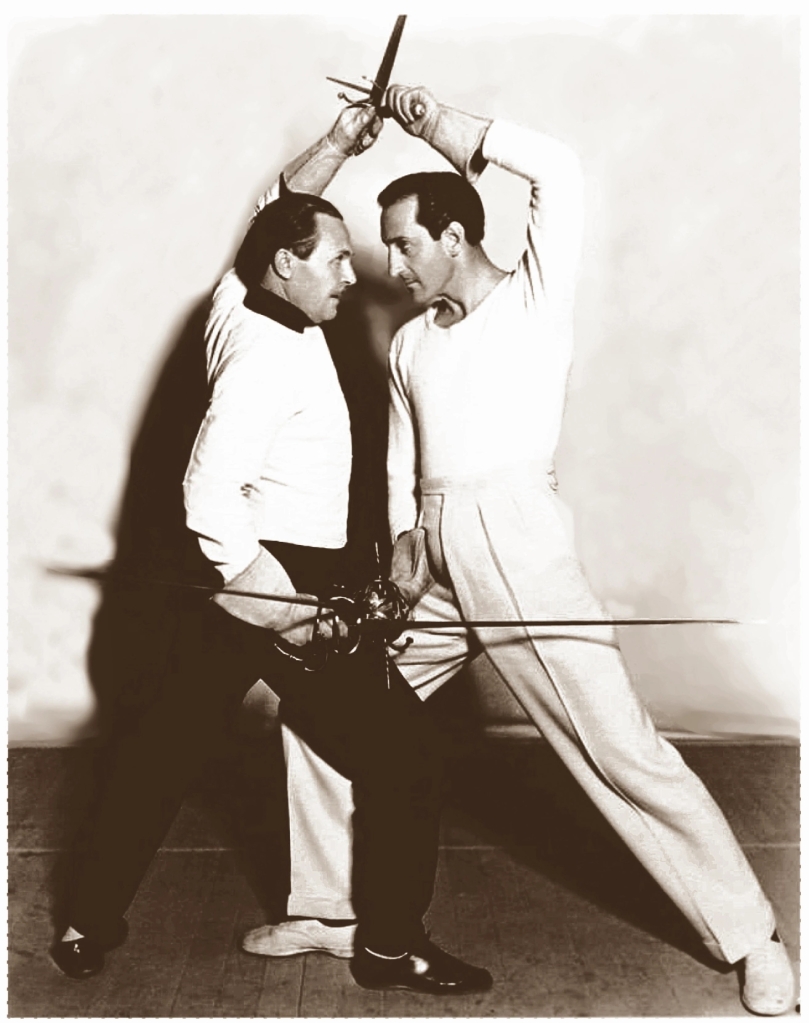

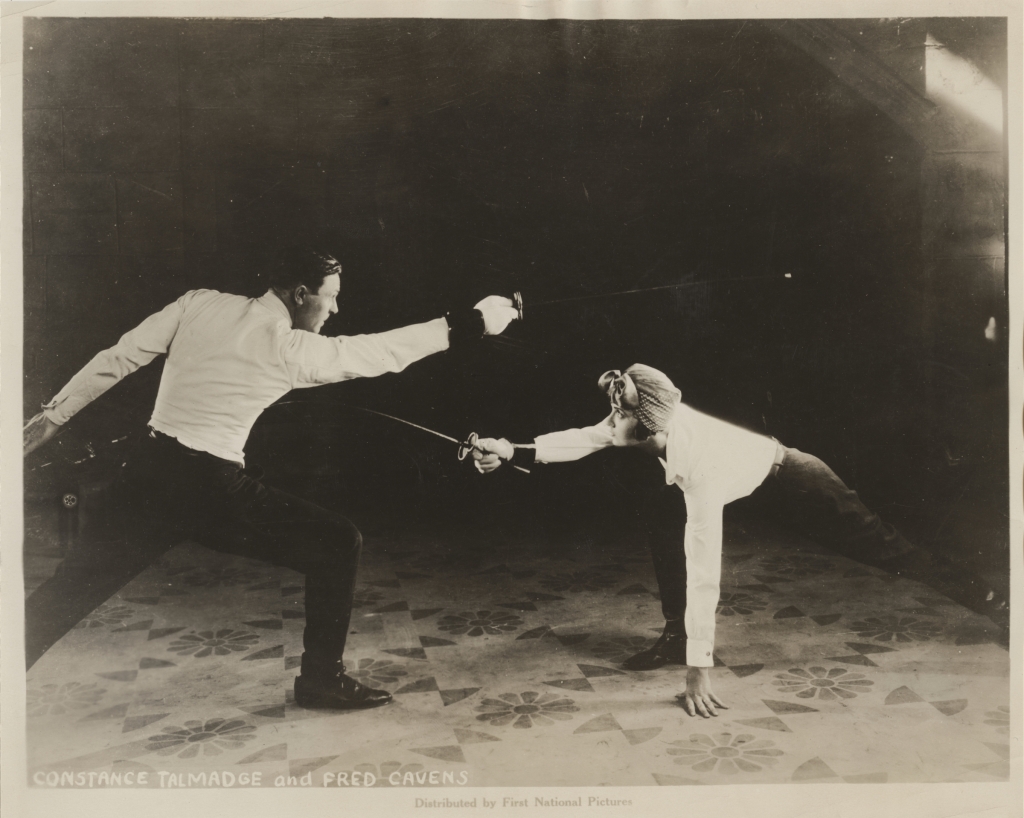

Classic film buffs, fencers, armchair adventurers, real swashbucklers, and romantics of many other stripes may debate over which film duel is the “best.” But no matter the standard, the duel between Errol Flynn as the hero Peter Blood and Basil Rathbone as the villain Levasseur in Captain Blood (1935) always makes the top few, often at number one. For me, there is no contest. There are a few far more historically accurate film duels (in fact, there are only a few historically accurate film duels at all), and there are a few film duels that are more technically proficient (for example, in The Mark of Zorro), but none in my opinion exceed this one in sheer excitement, drama, swashbuckling swordplay, and watching pleasure.

Of the duel, George MacDonald Fraser (The Pyrates, the Flashman series, &c, plus novelist, screenwriter, historian, swordsman, journalist, soldier, and more) had this to say in The Hollywood History of the World: “the most famous of screen duels…” and “Flynn v. Rathbone (Captain Blood) belongs in some swordsmen’s Valhalla of its own…” I cannot agree more.

The 1935 release, a remake of the silent 1924 film, was hotly anticipated. Newspapers and film magazines ate up the rumors, often created by Warner Bros. studio as part of its publicity campaign, regarding who would star in the film. At one point Robert Donat and Jean Muir were rumored in the LA Times to star, and later Bette Davis in Muir’s place. Many others were considered as well. But it was Irish-Australian newcomer Errol Flynn who landed the lead and after some reshoots fell naturally into the role.

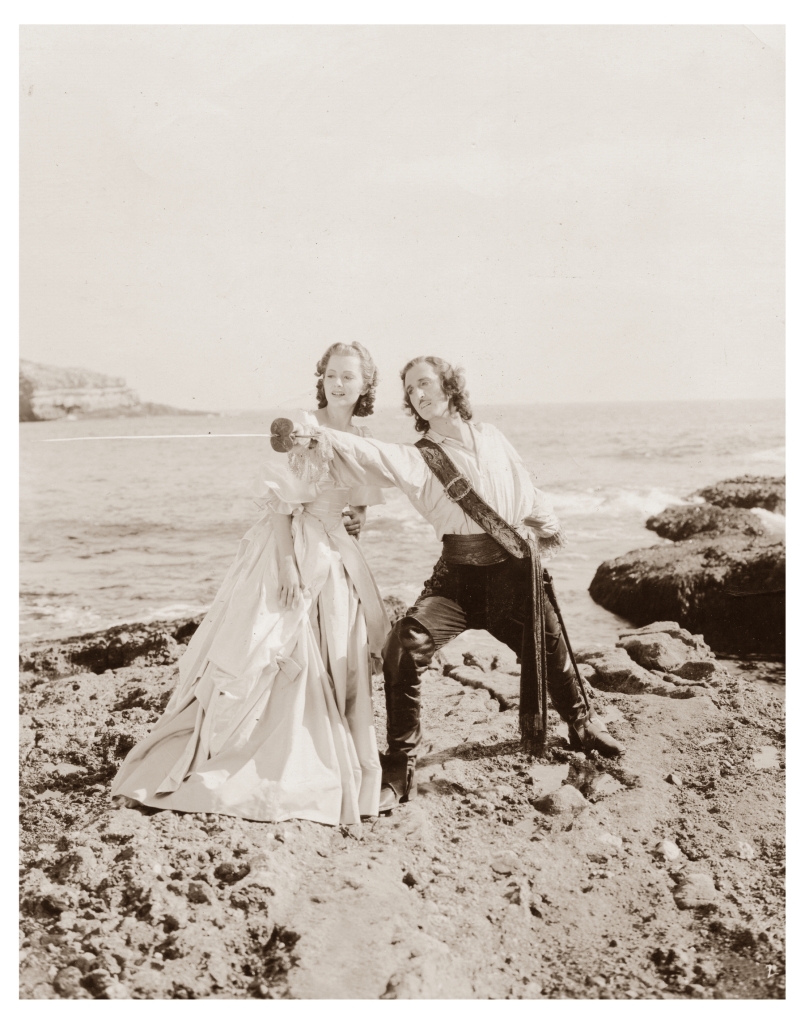

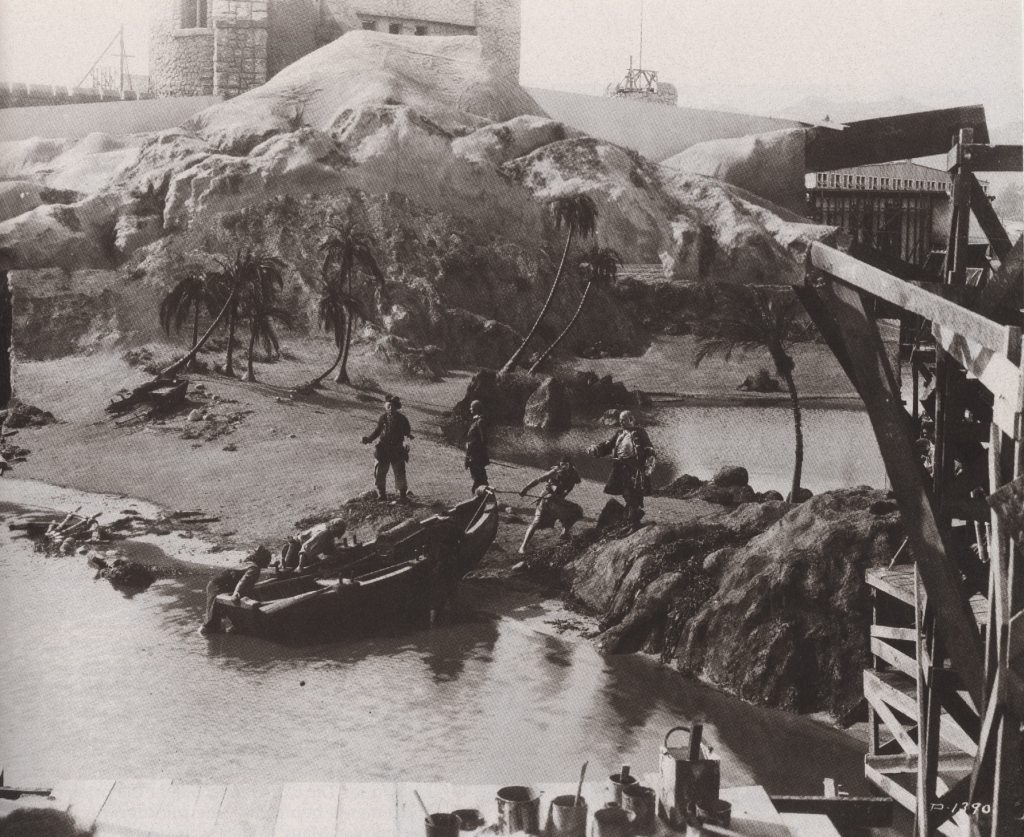

Costing a reported $1,000,000, the film was directed by Hungarian-born Michael Curtiz, and also starred nineteen-year-old Olivia de Havilland fresh from stage and film performances in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Basil Rathbone and an array of established character actors filled out the cast, supplemented by a number of real life adventurers among the ship crews and extras. Casey Robinson adapted the novel to the screenplay, simplifying it greatly but keeping the essentials. Released at Christmas, the swashbuckling romance was an immediate blockbuster and launched Flynn and de Havilland to stardom.

This post is a bit long and detailed, and occasionally technical when it comes to buccaneer history, fencing, and swords. Feel free therefore to jump around if you prefer, or just scroll through and check out the images. The major sections are marked. Reading the previous three “Duel on the Beach” posts is recommended but not required: In Fiction, in The Black Swan, and In Film. Some of the in-depth historical details below have been drawn from the annotations Treasure Light Press is writing for its forthcoming edition of Captain Blood.

The Novel Versus Film Duel

The 1935 duel was composed entirely from scratch, for the novel by Rafael Sabatini provides no significant detail. The author does include plenty of dramatic tension leading up to the swordfight, but for the assault itself we have only dialogue and minor notes.

[Spoiler Alert! Skip to the next header if you haven’t read the novel — or if you have and don’t need the refresher!].

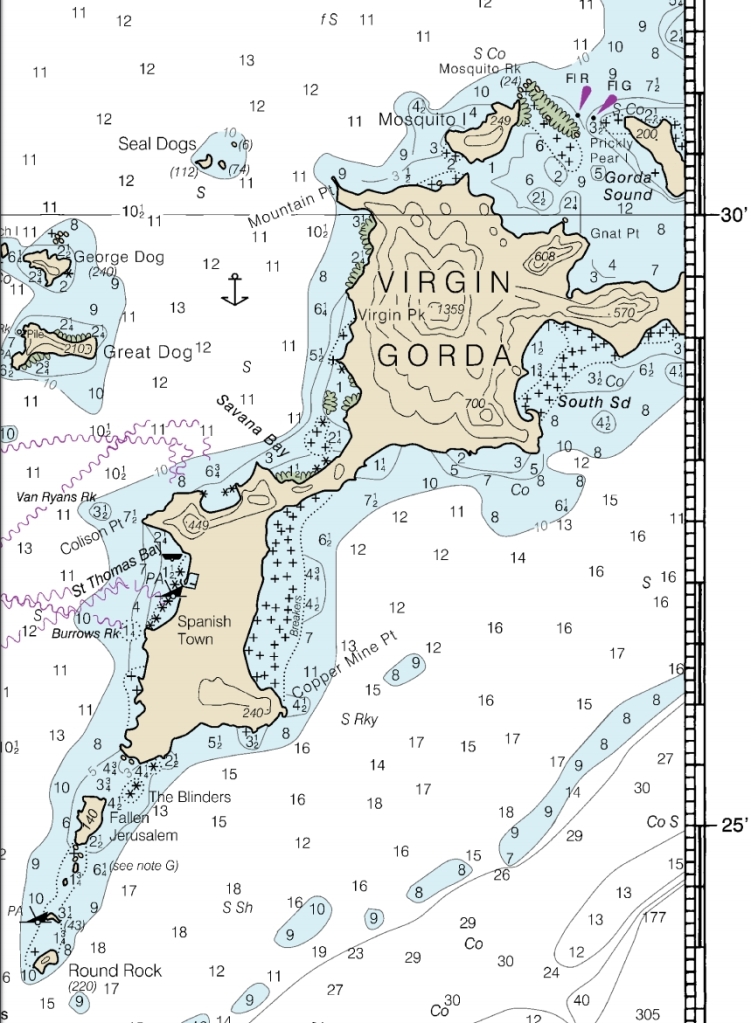

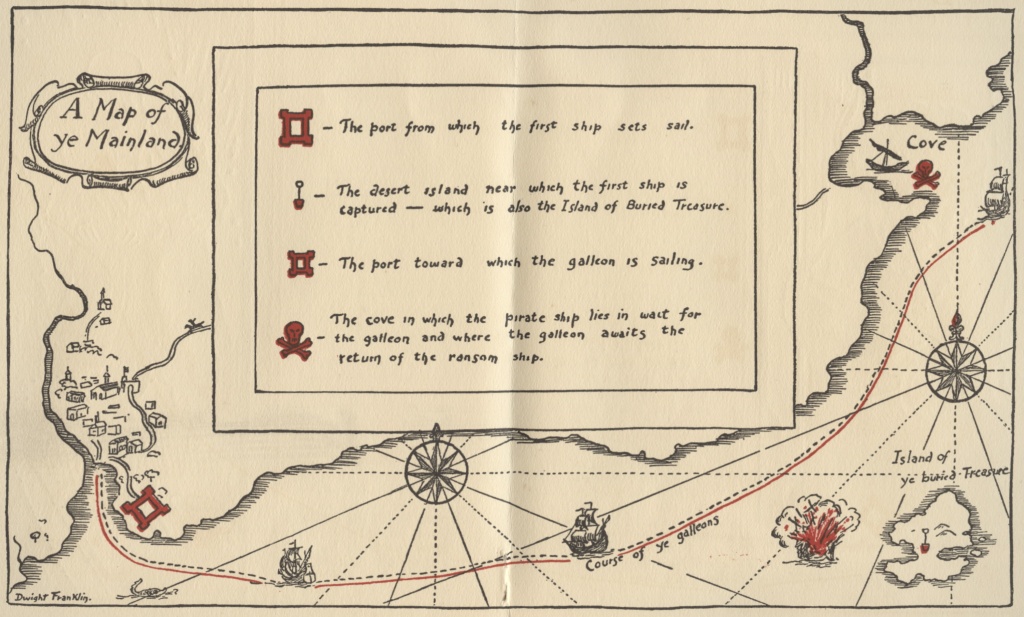

In the novel, Peter Blood and the crew of his ship the Arabella, believed by their consort Captain Levasseur and his crew of La Foudre to be well on their way back to Tortuga after the capture of a Spanish ship, have in fact been driven to the island of “Virgin Magra” (see below) where they discover Levasseur about to torture the son of the Governor d’Ogeron of Tortuga.

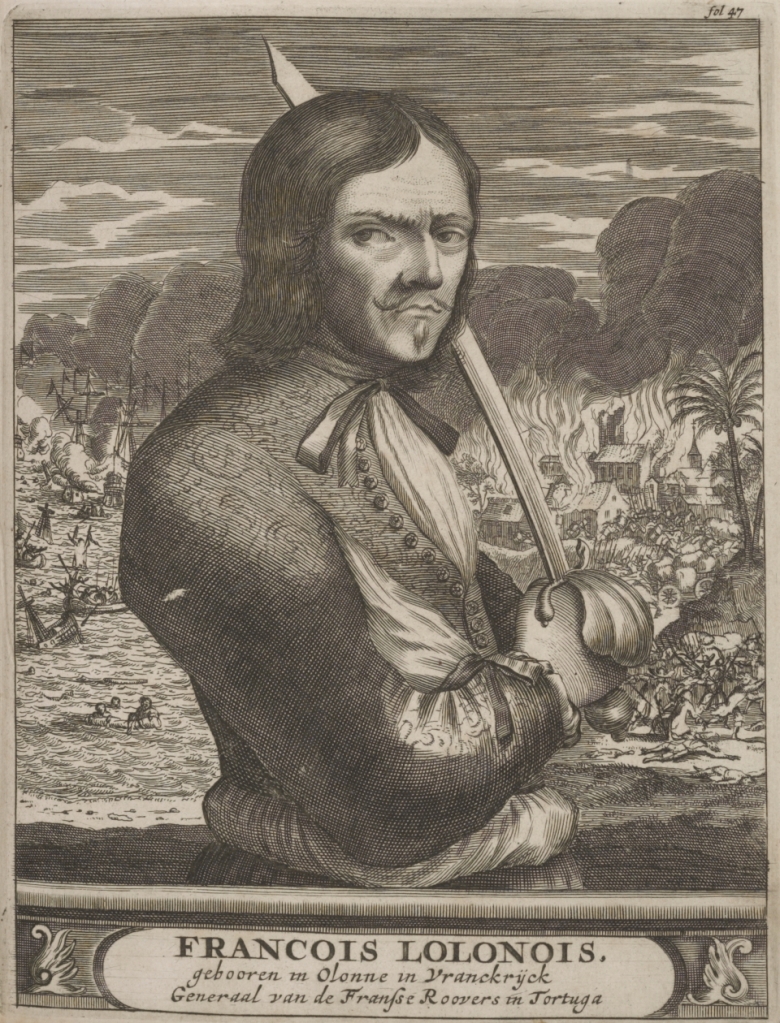

Levasseur has kidnapped the young man and his sister, murdering a Dutch captain and seizing his brig in the process. The cruel pirate, modeled on the infamous l’Ollonois and described as having served under him, is in lust with Madeleine d’Ogeron, and she believed she was in love with him until his murderous brutality was revealed. Now Levasseur intends to hold both for ransom, with the threat of “not marrying” Madeleine first if his demands are not met. It’s a classic set up of romantic adventure, with nuance as only Sabatini can add.

But just in time, Peter Blood and a handful of his officers and crew arrive as the marplot. After distracting Levasseur’s crew with an offer to pay the anticipated ransom for the woman and her brother up front, and casting their portion of the ransom in the form of pearls before swine, Peter Blood intends to remove Madeleine and her brother to his forty-gun Arabella, but Levasseur will have none of it.

From the novel:

“Levasseur, his hand on his sword, his face a white mask of rage, was confronting Captain Blood to hinder his departure.

“You do not take her while I live!” he cried.

“Then I’ll take her when you’re dead,” said Captain Blood, and his own blade flashed in the sunlight. “The articles provide that any man of whatever rank concealing any part of a prize, be it of the value of no more than a peso, shall be hanged at the yardarm. It’s what I intended for you in the end. But since ye prefer it this way, ye muckrake, faith, I’ll be humouring you.”

He waved away the men who would have interfered, and the blades rang together.”

There is really no more description of the duel except the following lines:

“It was soon over. The brute strength, upon which Levasseur so confidently counted, could avail nothing against the Irishman’s practised skill. When, with both lungs transfixed, he lay prone on the white sand, coughing out his rascally life, Captain Blood looked calmly at Cahusac across the body.”

A decade later Sabatini made up for the lack of detail by writing “The Duel on the Beach” (1931) and the novel based on it, The Black Swan (1932), in which a Peter Blood-like hero, Charles de Bernis, fights a duel with a Levasseur-like villain, Tom Leach. I’ve discussed the duel in detail here. In fact, this fictional duel probably inspired elements of the Captain Blood film duel.

However, in the film two of the principal characters have been changed due to the streamlining of the novel for the script: Madeleine d’Ogeron has been replaced by Arabella Bishop (Olivia de Havilland) and her brother by diplomat Lord Willoughby (Henry Stephenson).

The Dueling Terrain in the Novel: The Dunes and Beach of Virgin Magra

In the novel, the duel takes place on Virgin Magra (the Meager — Skinny, that is — Virgin), which is nothing more than Sabatini’s joke on Virgin Gorda (the Fat Virgin) in the British Virgin Islands. Virgin Gorda is arguably, depending on one’s eye, rather skinny than fat, and meager as compared to other islands in produce.

Even so, it is one of the most beautiful islands in the Caribbean. Mangrove, cactus including prickly pear, various scrub, and short deciduous trees (20 to 40 feet high) including allspice and quite a few others, made up most of the flora in the 17th century.

Coconut trees grow in small numbers on the island today but were probably not present in the 17th century. In fact, in the 17th century most Caribbean coconut palms, an introduced species, were on the Main, not the islands. Some small shrub palms up to fifteen feet tall probably did grow on the island, however. Species of Royal Palms grow on the island today but have been cultivated, and probably did not exist on there in the 17th century.

Sabatini is correct when he describes salt ponds on the island: in past centuries there were several bordered by mangrove swamps. Among the animals the visiting buccaneers might have encountered are sea turtles, iguanas, and large flocks of flamingos and ducks.

The Spanish and Dutch attempted small settlements in the mid-17th century on Virgin Gorda without success. In the second half of the 17th century Virgin Gorda was visited by loggers for boat- and shipbuilding timber, but these visitors established no permanent settlements. The island was probably also visited occasionally by salt-rakers.

In 1680 the English established small settlements on Virgin Gorda and nearby Tortola, the latter predominant, but the islands were soon raided by Spanish privateers or pirates, depending on one’s point of view. In the summer of 1687 the island was still apparently largely depopulated thanks to the Spanish raids.

A few families had probably been reinstalled at a small settlement at St. Thomas Bay, which would one day become known as Spanish Fort. Some authorities, based on period records, note fourteen free white males, a few free white females, and three slaves on the island at roughly this time. Very likely they hid from the buccaneer visitors, or at least from Levasseur and his French, were we to combine fact with fiction.

Given that Levasseur anchored his small eighteen-gun frigate La Foudre in the north lagoon, known as Gorda Sound and North Sound today, for repairs, the duel would have to be fought on one of the lagoon’s beaches. Although today there is only a significant dune presence at Savanna Bay, or as it was known in the 17th century, West Bay, there were other dune systems in the past, almost certainly some of them at the lagoon.

Hills — and a lazy lookout — would have screened the Arabella anchored to the southwest from view. Of course, Levasseur would have been advised to keep a good lookout (we know Peter Blood would have). Even so, Spanish pirates would surely have thought twice about attacking one or two stout buccaneer frigates.

Virgin Gorda in the 17th century has everything we imagine necessary for a duel on the beach between pirate captains — except coconut palms.

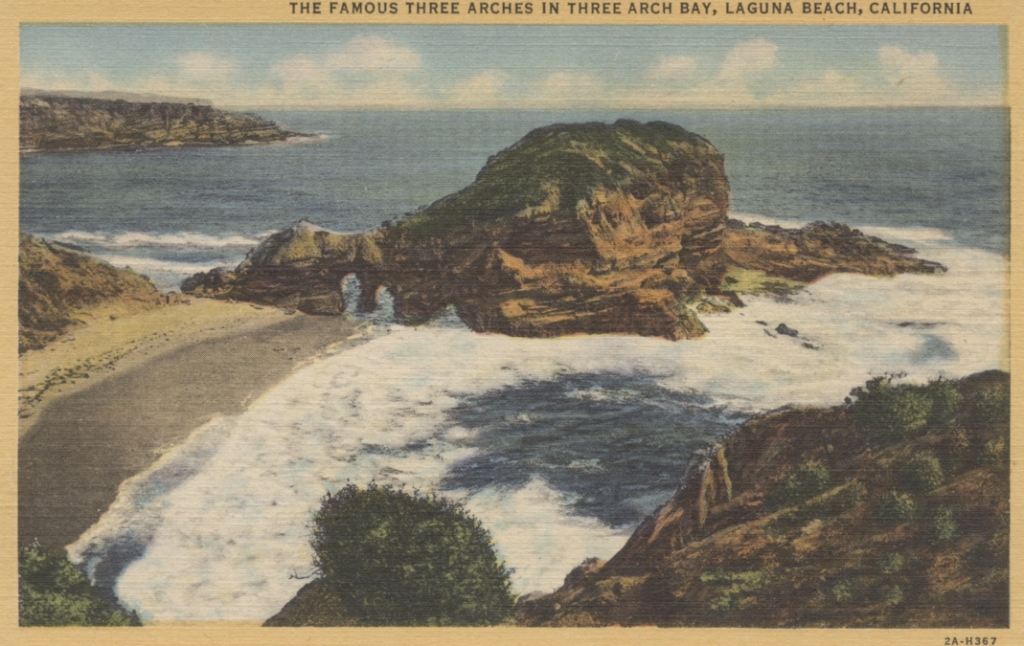

The Terrain in the Film: Three Arch Bay at Laguna Beach

The duel in the film was shot not on Catalina Island, as many fans often assume, but at Three Arch Bay at Laguna Beach. It is a classic Southern California vista: a sunny sandy shore amidst grand, craggy, evocative rocks. We will assume that the palm trees in the background were put there by the set designers and their crews, notwithstanding that Southern California (I lived in San Diego for twenty years and in LA for five) is known for its various palm trees, although the coconut is not one of them. The romantic vista adds to the scene, almost as a third character. The shot below is but one of many the beach was perfectly suited for, even demanded.

In fact, the location was chosen specifically to make the duel more exciting. From the original script by Casey Robinson: “The nature of our location will help a good deal here, for the fight not to be on the flat, but will range over the rocks and cliff edges of the rough country.”

Coincidentally, there is one location on Virgin Gorda that does look similar: “The Baths,” where sandy shore meets rock formations. It’s too far south, though, to answer the novel’s description of action and location, but following a novel closely has never stood in the way of Hollywood.

The Hero: Peter Blood

If you’ve read the novel or seen the 1935 film, you already know Peter Blood’s history: a physician (with surgical skill) accused of treason for treating a wounded rebel during the 1685 Monmouth Rebellion, he was convicted and sentenced to ten years transportation as an indentured servant at Barbados. During a Spanish raid of reprisal he and a number of his fellow rebels-convict board the Spanish frigate at anchor while the crew is indulging in pillage and rapine ashore, capture it, and destroy the Spaniards in their boats the following morning. The rebels-convict escape to Tortuga, an island just off the north coast of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti), and become buccaneers.

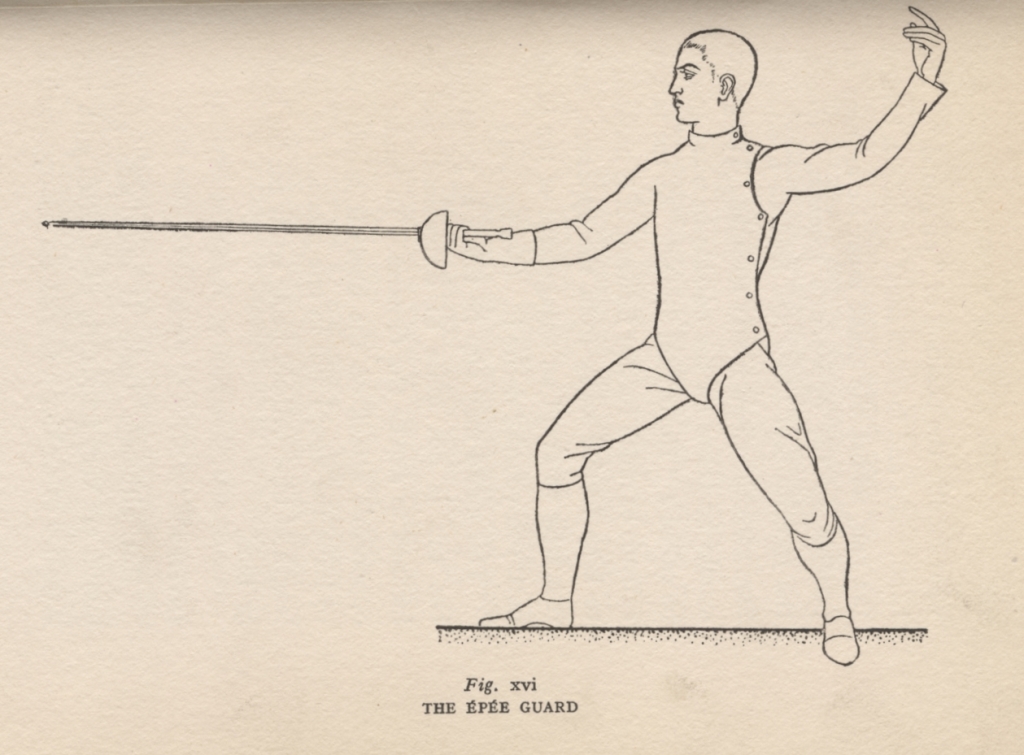

Given Peter Blood’s martial experience and Spanish imprisonment previous to setting down as a physician and eventually turning buccaneer, he would certainly be quite familiar with the French, Dutch, and Spanish schools of fence with thrusting weapons — the smallsword and the Spanish rapier — and also the cutlass given his Dutch naval experience, and would surely be able to handle a sword well-enough to defend himself in a variety of circumstances.