The Golden Age of Piracy:

The Truth Behind Pirate Myths

By Benerson Little

The truth behind the great pirate myths and

legends of the Golden Age (1655-1725).

In print: hardcover, trade paper, & ebook, in stores & online. Skyhorse Publishing, 2016.

Updates, comments, & errata may be found at the foot of the page.

Published Reviews

“Little (Fortune’s Whelp), a former Navy SEAL, takes the wind out of many a pirate’s sail in this charming examination of the many myths surrounding the seafaring rogues… Little has a deep affection for his subject that occasionally leads him to affectation, but his use of piratical jargon is more charming than jarring; clearly he’s having a good time, and so will readers. Packed with insight and adventure, Little’s book is sure to strike a note with armchair swashbucklers of all ages.”

— Publisher’s Weekly, September 11, 2017

“While a few other volumes discuss pirate myths, The Golden Age of Piracy goes far beyond these. Little sifts through the popular mythology and purposeful ideological speculation to introduce readers to the real pirates without turning a blind eye to their cruelty and crimes. That he does so in language that any reader will understand makes this a valuable resource and worthwhile addition to any pirate aficionado’s or historian’s library.”

—Cindy Vallar, Pirates and Privateers: The History of Maritime Piracy

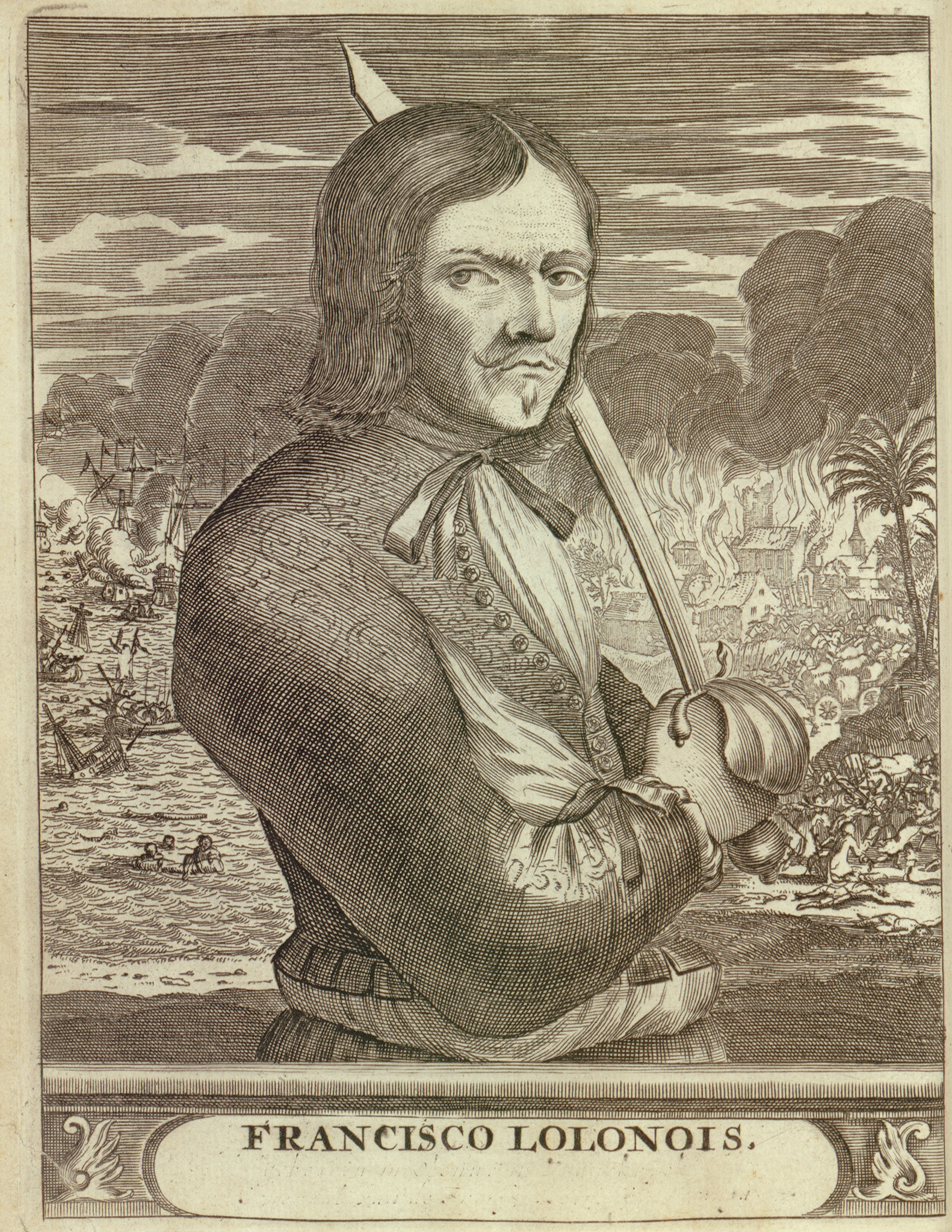

For thousands of years, pirates have terrorized the ocean voyager and the coastal inhabitant, plundered ship and shore, and wrought havoc on the lives and livelihoods of rich and poor alike.Around these desperate men has grown a body of myths and legends—fascinating tales that today strongly influence our notions of pirates and piracy. Most of these myths derive from the pirates of the “Golden Age,” from roughly 1655 to 1725. This was the age of the Spanish Main, of Henry Morgan and Blackbeard, of Bartholomew Sharp and Bartholomew Roberts.

The history of pirate myth is rich in action, at sea and ashore. However, the truth is far more interesting. In The Golden Age of Piracy, expert pirate historian Benerson Little debunks more than a dozen pirate myths that derive from this era—from the flying of the Jolly Roger to the burying of treasure, from walking the plank to the staging of epic sea battles—and shows that the truth is far more fascinating and disturbing than the romanticized legends.

Among Little’s revelations are that pirates of the Golden Age never made their captives walk the plank and that they, instead, were subject to horrendous torture, such as being burned or hung by their arms. Likewise, epic sea battles involving pirates were fairly rare because most prey surrendered immediately.

The stories are real and are drawn heavily from primary sources. Complementing them are colorful images of flags,ships, and buccaneers based on eyewitness accounts.

Associated Blog Posts

The Authentic Image of the Real Buccaneers of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini

The Authentic Image of the Boucanier

An Early Skull & Crossbones at Sea

Walking the Plank: An Associated Image

Of Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar Smoking Women

Gunpowder Spots: Pirates & “Tattoos”

Of Pirates & Parrots (& Monkeys, Too)

Pirate Books & Patereros: the Pirate’s Version of Fahrenheit 451

The Myth of Sharp’s Buccaneers, the Wreck of the Santa Maria de la Consolación, and Isla de Muerto

Swordplay Aloft: A Fictional But Entirely Enjoyable Pirate Trope

The Iconic “Spanish” Fort: Only a Spanish Galleon Says “Pirates” Better!

Captain Hook’s Hook: Its Most Likely Inspiration–And His Nemesis Crocodile’s Too!

The Women in Red: The Evolution of a Pirate Trope

Hollywood Boarding Actions: “Alright, My Hearties, Follow Me!”

The Fanciful, Mythical Calico Jack Rackham Flag

How a Mystery Pirate Captain Gave Us Rafael Sabatini’s Captain Blood & the Films of Errol Flynn

“The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow” by Howard Pyle

Notes, Commentary, & Errata

Prologue, rings on fingers. Additionally, Alexendre Exquemelin in his book, The Buccaneers of America–but the French edition only–notes that it was the custom of English buccaneers to wear gold fingers on their rings. This may be truthful or an exaggeration, as it is an excuse to accuse Henry Morgan and his buccaneers of recovering the bodies of dead buccaneers after the explosion of the HMS Oxford not for burial at sea or ashore, but to recover the jewelry on their fingers. The emphasis on the fact that this was an English practice may have been added to further the falsehood–some readers might question whether or not buccaneers actually wore rings. They tend to get in the way and get lost during physical activity.

The original Dutch, Spanish, and English editions all note that Morgan, quite possibly falsely, ordered the bodies recovered and the fingers with rings cut off so as to get at the rings. See Exquemelin, [Alexander Olivier O’Exquemelin], Histoire des Avanturiers Flibustiers qui se sont Signalez dans les Indes, 2 vols. (Paris: Jacques Le Febvre, 1699) or the 1686 edition, for the statement that it was customary for English buccaneers to wear gold rings.

Prologue, Robert Newton’s accent: in the (excellent) comic novel The Pyrates (1983) by George MacDonald Fraser, he notes Robert Newton’s effect on our idea of pirate speech, therefore preceding by some years a number of authors, myself included! 🙂

Prologue, pirate language: it’s quite possible that the expressions “Me hearties!” and “Dead men tell no tales” were popularized in the late 19th century by Mark Twain in Tom Sawyer. “My hearts!” dates to the seventeenth century, and was popularized in the 19th and 20th centuries as pirate speech in the form of “Me hearties!”

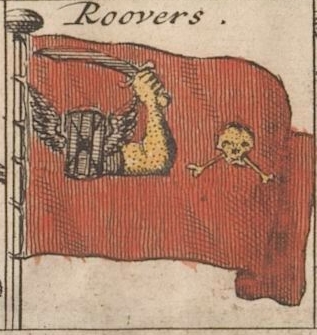

Chapter 1, an early black flag with skull and bones. Detailed on my An Early Skull & Crossbones at Sea, and More post is an imagined “Jolly Roger,” although it had yet to receive the name, dating to the 1640s.

Chapter 1, an early black flag with skull & bones in a flag book circa 1702: this is probably the earliest image of a “Jolly Roger” in a flag book, assuming the date is correct. The English flags are pre-1707 and the Spanish appears to date the document to circa 1702. Of course, we don’t know if the book were created within a single year or over many years. However, the image presents several problems in identification as to what it actually represents. (1) It is placed among flags of the North African “Barbary corsair” states, and may well represent one of their flags, although later instances of such flags show the skull or skull and bones on a red field, not black (see below). (2) The flag could represent that of Emanuel Wynne (1700), although his also had an hourglass and a single instance of a black skull & bones flag might not be sufficient for inclusion in a flag book. (3) If the book were illustrated over a decade or two — possible but reasonably unlikely, I think — the flag might represent those of the early 18th century pirates of the Americas who flew the black flag.

(4) The caption, translated from French, reads “flag that the filibusters fly.” At the time, the formal definition of flibustier in French dictionaries and other published works meant the “buccaneers of America.” English buccaneers were past history by 1702, but not quite yet the French flibustiers. However, the term by the early 18th century might have have a broader meaning in the public, as a synonym of pirate, forban, corsaire, &c., but I’m speculating. Could the flag have been that of flibustiers (aka buccaneers)? The only instance we know of buccaneers flying the flag was in the 1680s at Acaponeta during a land attack by French flibustiers: it was red (a “no quarter” flag) with white skull and bones. Still, it is possible that a similar black flag might have been flown by other buccaneers, but the evidence to date is lacking.

The image is from a “Book of naval and merchant flags, ca. 1702” in the Huntington Library. I was aware of the book’s existence but had never had a chance to examine it until Liam Taylor (UK lawyer and expert amateur pirate historian!) brought the digital version to my attention. For many years access to the works in the Huntington Library was difficult; I’m happy to see the change.

Chapter 1, Barbary and Turkish sea roving flags and flags of no quarter: I’ve since publication identified earlier images of these red flags of the Islamic corsairs, one dating to 1711, the others probably 1707 to 1711. Clearly these sea-going flags were around prior to the Anglo-American pirates who used similar flags, as were others I’ve noted in the book itself.

Chapter 1, the only real pirate flag of the early 18th century of which we have any detailed information on what one might actually have looked like:The only real “Golden Age” pirate flag we have an image of (there are no existing examples of real pirate flags from this era), just barely makes it into the era, as at 1729 it’s late for the period generally is regarded to end at 1725 or 1728. It’s also not the flag of an Anglo-American pirate, but a French one, from France and returning to France. The pirate in question is Jean-Thomas Dulaien, whom I’ve discussed along with his flag in the The Golden Age of Piracy. The first image below was reportedly created from the original flag, which was reportedly destroyed by order of Louis XIV; the second is of a woodblock or woodblock print made from the image.

Chapter 1, the captain of La Chavale: Jacques Gasser has identified the captain as François Rolle, quartermaster under Michel Andresson. La Chavale was originally named Le Favori under its former captain, François LeSage. For more information, see the Dictionnaire des Flibustiers des Caraïbes by Jacques Gasser (Les Sables d’Olonne, France: Editions Beaupre, 2017).

Chapter 1, the Jolly Roger: a remote possibility of part of the origin of the term is as a joke on the term “Jolly Tar” which shows up in the early 18th century (and may have been in use prior).

Chapter 1, Blackbeard’s purported but mythical flag origin: Historian Ed Fox has pointed out that the horned Blackbeard flag first appears in The Mariner’s Mirror (1912, vol. 2, no. 3) to accompany the “Answers” section on a query about pirate flags. It is fanciful but is based on a legitimate period description of a pirate flag. A later artist or publisher ascribed it, with minor modification emphasizing devil horns, to Blackbeard.

Chapter 1, the purported Calico Jack Rackham flag: more details here in The Fanciful, Mythical “Calico Jack Rackham” Pirate Flag.

Chapter 1, pirate flags with crossed swords, if any: if there were an early 18th century origin to the Rackham flag, we might blame Daniel Defoe’s Captain Singleton, a pirate novel published in 1720: Captain Bob [Singleton] flew “a black flag, with two cross daggers in it.” We cannot be certain this is the ultimate origin, for the idea of crossed swords is quite common throughout history.

Chapter 1, the St. Augustine Pirate Museum flag, claimed as an original skull and bones: in the text and notes I mention three flags claimed to original piratical skull and bones. Of them, one, a North African flag, was probably flown ashore and had nothing to do with corsairs. Another, also North African, may be original but it is impossible to know. I’ve finally, by accident, had access to “provenance,” such as it is, of the third one, a flag on display at the St. Augustine Pirate Museum. My original inquiries into provenance some years ago were ignored, always a red flag (please pardon the pun!). My original deduction, that the flag is fake, was basically confirmed by the museum’s conservator, if not in so many words, when he felt obligated to answer attacks on the flag in a recent series of posts in a pirate group on Facebook.

The conservator did not confirm the flag as fake, but noted that it was acquired from the estate of treasure hunter Art McKee who used to fly it, and that there is no data, history, or provenance confirming it as an original pirate flag other than carbon dating of the fabric, which places it in the nineteenth century — or quite possibly not, given the inaccuracy in carbon dating for objects created in the past three to four centuries. In other words, it’s a fake as I already had deduced. According to RCD Lockinge, a UK-based radio-carbon dating company, “Objects with ages which are suspected to lie in the range of ca. 1650 to 1950 AD are usually unsuitable for carbon dating as the calibration curve used to convert a carbon-14 measurement into a calendar age is irregular in this ‘period of uncertainty’.”

Chapter 2, matches under Blackbeard’s hat: in the (excellent) comic novel The Pyrates by George MacDonald Fraser, it is suggested that the beard of Firebeard, a character based on Blackbeard, would be easily set alight, therefore again preceding my conclusion by a quarter century! And perhaps subconsciously influencing my own conclusion too! 🙂

Chapter 4, walking the plank: Dunkirkers–privateers from Dunkirk, Ostend, and Nieuwpoort in the Spanish Low Countries (Flanders) and flying the Spanish flag–were so successful against the Dutch in the late 16th century that Dutch men-of-war had orders to throw captured Dunkirker crews overboard, although these standing orders were not always followed. See A.P. van Vliet, “The influence of Dunkirk Privateering in the North Sea (Herring) Fishery During the Years 1580–1650, in J. Roding and L. Heerma van Voss, eds., The North Sea and Culture (1550-1800), Proceedings of the International Conference held at Leiden 21-22 April 1995.

Chapter 6, the attack on the Gran San Pablo: Jean-Pierre Moreau in Pirates (Paris: Tallandier, 2006) mentions Julien Santer as either captain or crew of the Popa Azul, suggesting the ship was one of the vessels attacking the Gran San Pablo. Santer lost an arm in the action.

Chapter 6, de Graff’s fight against the Francesa: research subsequent to publication indicates the armament, route, and some of the actual action. El Santissimo Sacramento (the Blessed Sacrament), known by her crew as La Francesa because she was captured from the French and taken into Spanish service, is of is 240 tons burthen and she mounts twenty-four small guns, probably of six and four or three pound shot, and ten patereros or swivel guns. She is manned with 64 infantes (infantry), 24 artilleros (gunners), and 36 marineros (seamen): a total of 124 fighting men. She is transporting the situado because she was left behind by the treasure fleet. Neither Havana nor San Juan had ships of force to carry the large payroll, but the Francesa was by luck in place to take on the task.The frigate departed Havana on July 8, 1682, taking the long northern route along the Florida coast, then into the Atlantic at 38 degrees north latitude, then south to Puerto Rico. It is a slow but safe route: it avoids both constant beating to windward and, importantly, pirates. But de Graff has excellent intelligence, probably via “la aguada de Sancta Lucia” on the Cuban coast where he would put in for supplies and information from a man named Montiel. Knowing how slowly the frigate will make its way to Puerto Rico, beats to windward along the coasts of Cuba and Hispaniola and lies in wait in the Mona Passage. On August 6 the situado ship, roughly twelve leagues from Aguada de Puerto Rico, sights a sail in pursuit.When he sights the ship in pursuit, Manuel Delgado follows his standing orders: he runs. At any and all cost is he to deliver the situado safe and sound. The chase lasts as many as sixty or more miles, from off the coast of Aguada de Puerto Rico to the eastern end of Hispaniola. As de Graff’s Tigre comes within range, Delgado opens fire with his stern chasers, to little avail.Unfortunately, perhaps in part due to overheating, as one witness suggested, one of the stern chasers explodes, damaging the frigate’s stern and doubtless causing injuries. Seeing that a fight is inevitable, some of Delgado’s officers urge him to turn and fight, but he replies that he has orders not to do so. His duty is to protect the treasure at all costs—to run if he can. And so he does, as long as he can, hoping to make it to Santo Domingo before de Graff comes up with him.According to the Spanish account, de Graff eventually comes alongside, and with a combination of broadside, small arms, and grenades, grapples the Spaniard and boards. Forty-seven of Delgado’s men are killed and more than forty are wounded.Most of these details are taken from the excellent books, El Corso en Cuba Siglo XVII by César García del Pino (2001) and La Defensa de La Isla de Cuba en La Segunda Mitad del Siglo XVII by Francisco Castillo Melendez (1986).

Chapter 6, tonnage of de Graff’s Neptune in the fight against the Armada de Barlovento: at 273 tons, translated to toneladas para de guerra from toneladas para de merchantes (with which the ship, having been a slaver, was measured in Spanish records) the Neptune would be roughly equivalent to roughly 320 tons English burthen, still only slightly more than half the size of its two adversaries. A ship of this size might carry no more than 36 great guns (she was mounted with 34 when captured). The rest, probably no more than a dozen, and certainly no more than a score, would be swivels in various forms.

Chapter 6, tonnage and armament of the Burgos and Concepción during de Graff’s fight against them: according to Las Fragatas de vela de la Armada Española 1650-1853 by Enrique Garcia-Torralba Pérez, a 1691 proposal to build the Capitana and Almirante of the Armada de Barlovento proposed one ship of 600 tons and 60 guns, to mount 18 pounders on the lower tier, 8 pounders on the upper, and 4 pounders on the castillos or quarterdeck, poop, and perhaps forecastle. The other would be of 550 tons and similarly armed. Given that these ships were to be built in Amsterdam and armed either there or in Cadiz (in most cases, new ships were armed at Cadiz, and older ones rearmed there, whether built in Spain, Flanders, or the Netherlands), they might have carried this armament rather than a lighter one as was often the case with Armada de Barlovento ships built in Veracruz, Mexico due to a scarcity of naval guns of appropriate size. If it was the case that the Burgos and Concepción were similarly, and therefore more heavily, armed than I speculated, it would make de Graff’s feat all the more impressive. Side note regarding the armament of Spanish frigates: those of 500 to 600 tons might be armed with 40 to 60 guns, ranging from 10 to 18 pounders on the lower tier, 6 to 8 pounders on the upper, and 4 pounders on the castillos, if any. Spanish treasure ships of this size might carry half the number of guns in order to make space for cargo, relying on ship hull strength, the large number of crew and passengers, and the convoy system for defense.

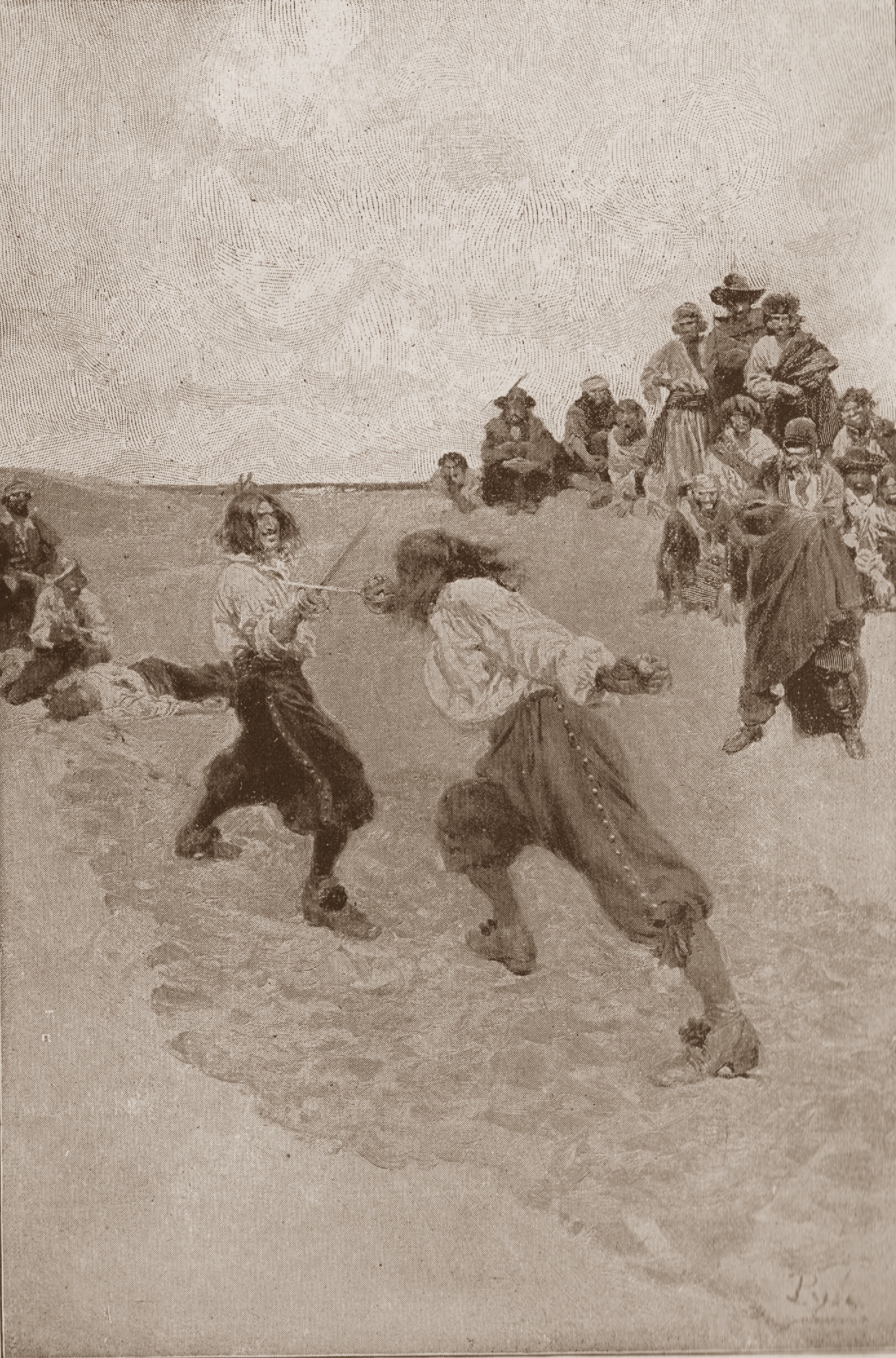

Chapter 8, dueling: In Exquemelin’s 1684/1685 Crooke edition of The Buccaneers of America is an account of a duel between an English buccaneer and a French flibustier; the Englishman had stolen the marrow bones from the Frenchman who was butchering the beast for provision, under Henry Morgan’s orders, after the sack of Puerto del Principe. “Being come to the place of duel, the Englishman drew his sword treacherously against the Frenchman, wounding him in the back, before he had put himself into a just posture of defence; whereby he suddenly fell dead upon the place.” The incident caused a rupture between the French and English. Morgan ordered the Englishman arrested, and, to keep amity between the buccaneers of the two nations, hanged the murderer in Jamaica.

However, Exquemelin’s original French editions (1686, 1699) as well as the first Dutch edition (1678) state that the duel was fought, as was the usual case among most buccaneers, with muskets. The Englishman, Exquemelin writes in the French editions, was an inferior shot to the Frenchman and so shot him in the back, for which, per Morgan’s orders, he had his “head broken”–was put to death–immediately.

Chapter 10, Spanish laws on how to deal with captured pirates: in the text in reference to the black buccaneer named Diego (1686), I note that Spanish laws at the time provided for death sentences for pirate leaders only. The law dates to a February 21, 1685 Royal cedula, which stated that the pirate leader is to be shot or hanged, after determination of guilt, where captured. The remaining pirates are to be sent to Spain. Notwithstanding, it appears in most cases that captured pirates were not sent to Spain. Royal cedulas of December 31, 1672 and September 27, 1673 required that captured pirates not be sent to Spain.

Chapter 10, black pirate captains of full African blood: In the text I note that to date, although a number of mulatto (mixed race black and white) pirate, buccaneer, and privateer captains are documented, none of full African blood is that I could find. Since publication I ran across details of Josiah Simms, the black captain of a trading sloop who was accused of failing to pay customs and also of piracy, via the plundering of a sloop, at New Providence in 1701. The sloop was owned by Read Elding, the former mulatto governor of New Providence Island. Elding himself was also accused of piracy and a number of other crimes. But before Simms and his crew could be tried, Elding, who had been deposed from office, seized control of the government via local riots in support of him, and managed to get them away. See “An Answer to a Libel” by Elias Haskett, 1702[?].

Chapter 12, the flibustier attack on de Melgar’s treasure salvors: The flibustiers were commanded by Pierre Bréha, the diminutive of Abraham, his real surname was reportedly Bart. He sailed a very small frigate named the Saint-François armed with 2 guns and manned with 70 rovers. Some accounts report that Bréha was accompanied by the French flibustier Jean Blot who commanded a small frigate with 2 guns and 44 men. However, given the Spanish accounts, it’s likely that only one of the flibustier vessels was present during the action. Both were together in the aftermath. Note: some authorities have confused Michel Andresson aka Michiel Andrieszoon, with Pierre Bréha.

Chapter 12, another possible source of the myth of buried pirate treasure: in 1750 part of a Spanish treasure fleet ran aground on the coast of North Carolina during a storm. The Governor of Santo Domingo recovered 200,000 p8 from his ship and hired two local sloops to return him to Santo Domingo. The crew of one of the sloops, however, sailed away with much or all of the treasure and buried it on Norman’s Island near Tortola, earning them the appellation of pirates (although embezzlement is a more likely charge). Quickly learning of the treasure, some of the inhabitants of Tortola dug it up and kept it for themselves. Governor Gilbert Fleming went to Tortola to attempt to restore it to its rightful Spanish owners but largely failed, recovering only 20,428 p8, and leaving half again as much in local hands. Any remaining treasure was never recovered officially.

Chapter 12, Olivier Levasseur aka La Bouse: a few additional notes regarding his name and purported treasure. While sailing in agreement with the pirate Taylor commanding the Cassandra, in mid-1722 Levasseur tried to desert his consort but was instead deposed from command by his own crew. Eyewitness Jacques du Bucquoy reported that Levasseur and his fellow mutineers were whipped, and their possessions, almost certainly including their valuable Nossa Senhor do Cabo plunder, confiscated for the benefit of the crew. In the fall, Levasseur was given back command of the Defense and, parting from Taylor who was ready to accept amnesty, sailed to Madagascar. In 1724 he was offered a pardon by the French government but refused it. Afterward he worked as a local pilot at Madagascar until he was captured by a French frigate in April, 1730. He was tried, convicted, and hanged for piracy three months later on Île Bourbon. Almost certainly he owned no great treasure when captured.

As noted, Levasseur’s nom de guerre La Buse had many variants—La Buse, la Bouze, Labour, Laboar, Dubourg, La Bouche, and more—making it difficult to determine what it actually meant. The most common, La Buse, translates as buzzard, which in Europe was a species of bird of prey considered useless for falconry, from which came a second common meaning: a stupid person—one who cannot be trained, in other words. “You can’t make a hawk from a buzzard [buse], nor a clever man from a fool,” ran a French proverb. Another version of Levasseur’s nickname might mean mouth, another might even mean cow dung.

Chapter 12, another early instance of fictional buried treasure: in Daniel Defoe’s The King of Pirates, his fictional tale of Benjamin Avery, the pirate captain and two of his surviving companions bury everyone’s treasure somewhere ashore in the Bay of Campeche, fearing to lose it and unable to carry it all as a few make a journey along the coast of the Spanish Main. The buccaneers bury their treasure in a pit twelve feet deep and recover it a few years later, worth some 8,000 p8 per man, a total of 80,000 p8. Defoe is clever enough to note that most of it is in gold — otherwise no man would be able to carry his booty! Each share is also extraordinarily large, a dozen or more times larger than that of most profitable voyages. Unfortunately, it’s almost a rule that fiction must exaggerate. In this early instance of fictional buried treasure, Defoe has provided a plausible reason for burying treasure — the buccaneers have been marooned more or less on Spanish territory for two years. Later storytellers largely abandoned such reasoning.

Copyright Benerson Little, 2016-2022. Last updated October 11, 2022.