Home » Fencing

Category Archives: Fencing

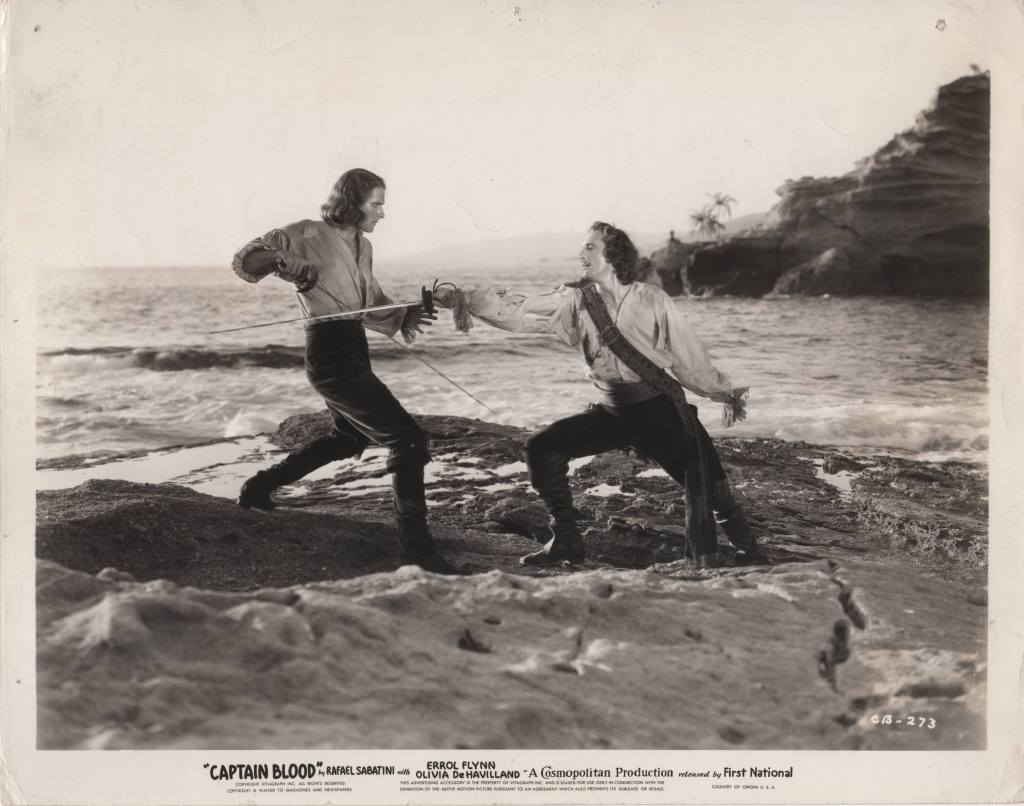

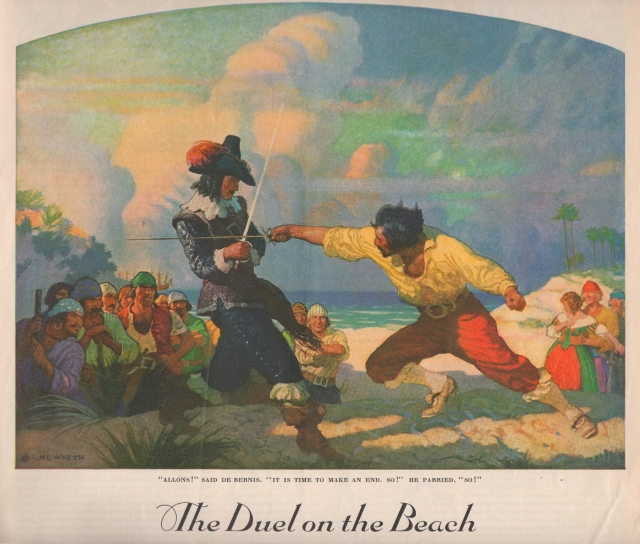

The Duel on the Beach, Part IV: Flynn versus Rathbone in Captain Blood!

Classic film buffs, fencers, armchair adventurers, real swashbucklers, and romantics of many other stripes may debate over which film duel is the “best.” But no matter the standard, the duel between Errol Flynn as the hero Peter Blood and Basil Rathbone as the villain Levasseur in Captain Blood (1935) always makes the top few, often at number one. For me, there is no contest. There are a few far more historically accurate film duels (in fact, there are only a few historically accurate film duels at all), and there are a few film duels that are more technically proficient (for example, in The Mark of Zorro), but none in my opinion exceed this one in sheer excitement, drama, swashbuckling swordplay, and watching pleasure.

Of the duel, George MacDonald Fraser (The Pyrates, the Flashman series, &c, plus novelist, screenwriter, historian, swordsman, journalist, soldier, and more) had this to say in The Hollywood History of the World: “the most famous of screen duels…” and “Flynn v. Rathbone (Captain Blood) belongs in some swordsmen’s Valhalla of its own…” I cannot agree more.

The 1935 release, a remake of the silent 1924 film, was hotly anticipated. Newspapers and film magazines ate up the rumors, often created by Warner Bros. studio as part of its publicity campaign, regarding who would star in the film. At one point Robert Donat and Jean Muir were rumored in the LA Times to star, and later Bette Davis in Muir’s place. Many others were considered as well. But it was Irish-Australian newcomer Errol Flynn who landed the lead and after some reshoots fell naturally into the role.

Costing a reported $1,000,000, the film was directed by Hungarian-born Michael Curtiz, and also starred nineteen-year-old Olivia de Havilland fresh from stage and film performances in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Basil Rathbone and an array of established character actors filled out the cast, supplemented by a number of real life adventurers among the ship crews and extras. Casey Robinson adapted the novel to the screenplay, simplifying it greatly but keeping the essentials. Released at Christmas, the swashbuckling romance was an immediate blockbuster and launched Flynn and de Havilland to stardom.

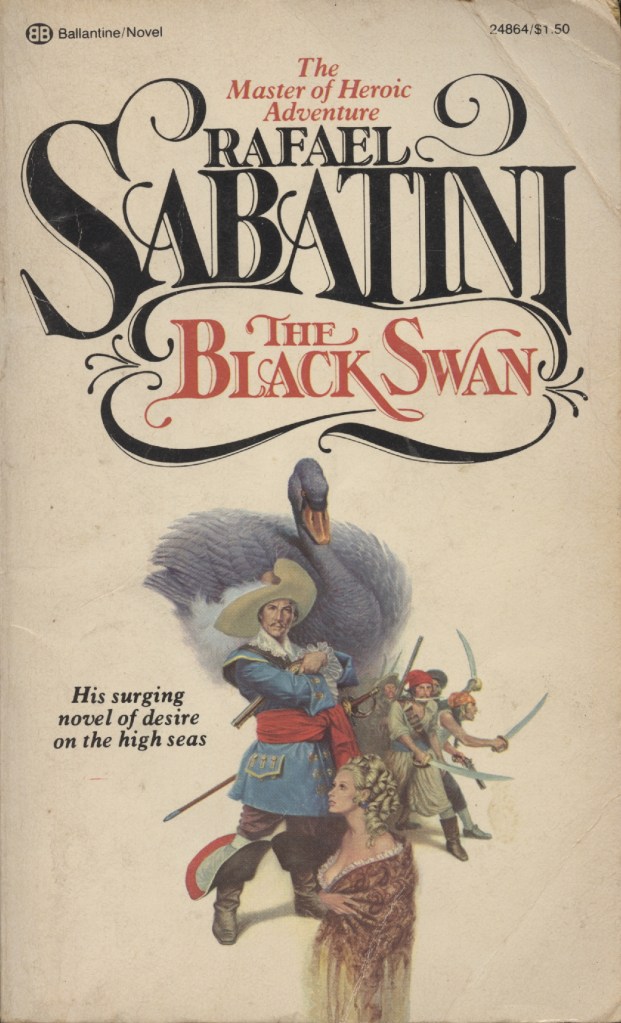

This post is a bit long and detailed, and occasionally technical when it comes to buccaneer history, fencing, and swords. Feel free therefore to jump around if you prefer, or just scroll through and check out the images. The major sections are marked. Reading the previous three “Duel on the Beach” posts is recommended but not required: In Fiction, in The Black Swan, and In Film. Some of the in-depth historical details below have been drawn from the annotations Treasure Light Press is writing for its forthcoming edition of Captain Blood.

The Novel Versus Film Duel

The 1935 duel was composed entirely from scratch, for the novel by Rafael Sabatini provides no significant detail. The author does include plenty of dramatic tension leading up to the swordfight, but for the assault itself we have only dialogue and minor notes.

[Spoiler Alert! Skip to the next header if you haven’t read the novel — or if you have and don’t need the refresher!].

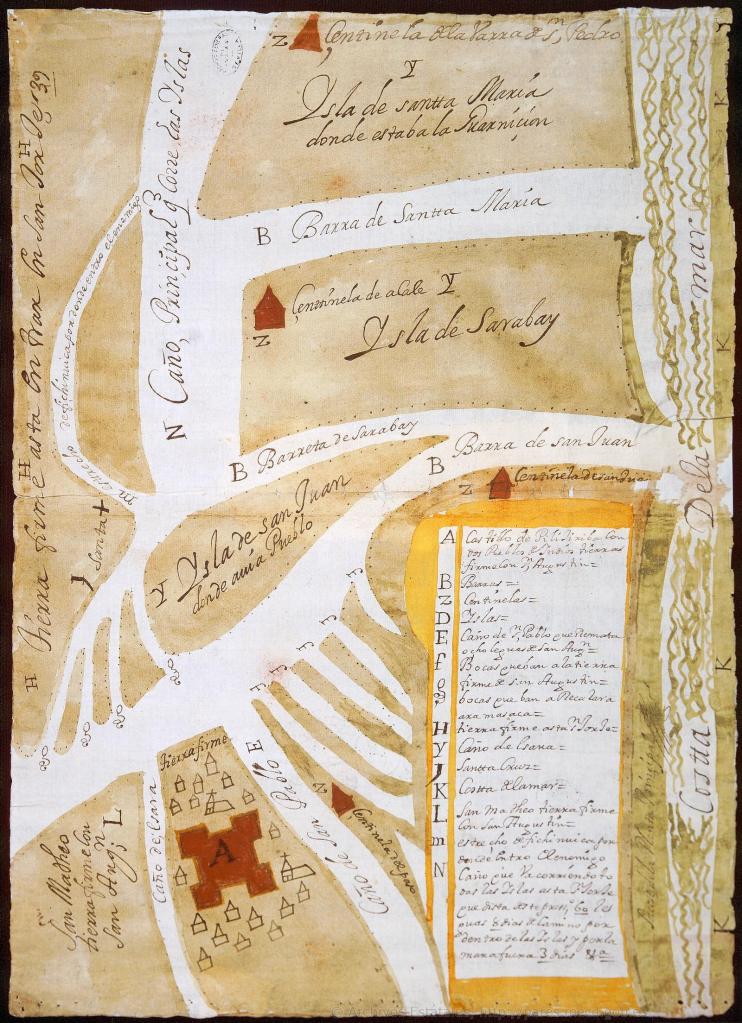

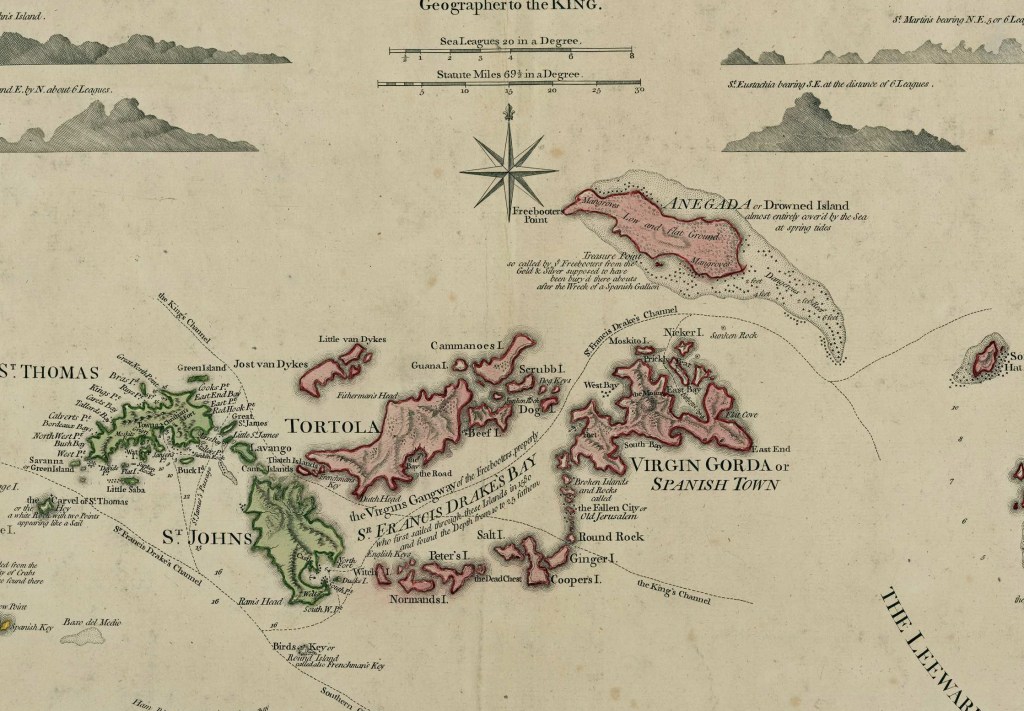

In the novel, Peter Blood and the crew of his ship the Arabella, believed by their consort Captain Levasseur and his crew of La Foudre to be well on their way back to Tortuga after the capture of a Spanish ship, have in fact been driven to the island of “Virgin Magra” (see below) where they discover Levasseur about to torture the son of the Governor d’Ogeron of Tortuga.

Levasseur has kidnapped the young man and his sister, murdering a Dutch captain and seizing his brig in the process. The cruel pirate, modeled on the infamous l’Ollonois and described as having served under him, is in lust with Madeleine d’Ogeron, and she believed she was in love with him until his murderous brutality was revealed. Now Levasseur intends to hold both for ransom, with the threat of “not marrying” Madeleine first if his demands are not met. It’s a classic set up of romantic adventure, with nuance as only Sabatini can add.

But just in time, Peter Blood and a handful of his officers and crew arrive as the marplot. After distracting Levasseur’s crew with an offer to pay the anticipated ransom for the woman and her brother up front, and casting their portion of the ransom in the form of pearls before swine, Peter Blood intends to remove Madeleine and her brother to his forty-gun Arabella, but Levasseur will have none of it.

From the novel:

“Levasseur, his hand on his sword, his face a white mask of rage, was confronting Captain Blood to hinder his departure.

“You do not take her while I live!” he cried.

“Then I’ll take her when you’re dead,” said Captain Blood, and his own blade flashed in the sunlight. “The articles provide that any man of whatever rank concealing any part of a prize, be it of the value of no more than a peso, shall be hanged at the yardarm. It’s what I intended for you in the end. But since ye prefer it this way, ye muckrake, faith, I’ll be humouring you.”

He waved away the men who would have interfered, and the blades rang together.”

There is really no more description of the duel except the following lines:

“It was soon over. The brute strength, upon which Levasseur so confidently counted, could avail nothing against the Irishman’s practised skill. When, with both lungs transfixed, he lay prone on the white sand, coughing out his rascally life, Captain Blood looked calmly at Cahusac across the body.”

A decade later Sabatini made up for the lack of detail by writing “The Duel on the Beach” (1931) and the novel based on it, The Black Swan (1932), in which a Peter Blood-like hero, Charles de Bernis, fights a duel with a Levasseur-like villain, Tom Leach. I’ve discussed the duel in detail here. In fact, this fictional duel probably inspired elements of the Captain Blood film duel.

However, in the film two of the principal characters have been changed due to the streamlining of the novel for the script: Madeleine d’Ogeron has been replaced by Arabella Bishop (Olivia de Havilland) and her brother by diplomat Lord Willoughby (Henry Stephenson).

The Dueling Terrain in the Novel: The Dunes and Beach of Virgin Magra

In the novel, the duel takes place on Virgin Magra (the Meager — Skinny, that is — Virgin), which is nothing more than Sabatini’s joke on Virgin Gorda (the Fat Virgin) in the British Virgin Islands. Virgin Gorda is arguably, depending on one’s eye, rather skinny than fat, and meager as compared to other islands in produce.

Even so, it is one of the most beautiful islands in the Caribbean. Mangrove, cactus including prickly pear, various scrub, and short deciduous trees (20 to 40 feet high) including allspice and quite a few others, made up most of the flora in the 17th century.

Coconut trees grow in small numbers on the island today but were probably not present in the 17th century. In fact, in the 17th century most Caribbean coconut palms, an introduced species, were on the Main, not the islands. Some small shrub palms up to fifteen feet tall probably did grow on the island, however. Species of Royal Palms grow on the island today but have been cultivated, and probably did not exist on there in the 17th century.

Sabatini is correct when he describes salt ponds on the island: in past centuries there were several bordered by mangrove swamps. Among the animals the visiting buccaneers might have encountered are sea turtles, iguanas, and large flocks of flamingos and ducks.

The Spanish and Dutch attempted small settlements in the mid-17th century on Virgin Gorda without success. In the second half of the 17th century Virgin Gorda was visited by loggers for boat- and shipbuilding timber, but these visitors established no permanent settlements. The island was probably also visited occasionally by salt-rakers.

In 1680 the English established small settlements on Virgin Gorda and nearby Tortola, the latter predominant, but the islands were soon raided by Spanish privateers or pirates, depending on one’s point of view. In the summer of 1687 the island was still apparently largely depopulated thanks to the Spanish raids.

A few families had probably been reinstalled at a small settlement at St. Thomas Bay, which would one day become known as Spanish Fort. Some authorities, based on period records, note fourteen free white males, a few free white females, and three slaves on the island at roughly this time. Very likely they hid from the buccaneer visitors, or at least from Levasseur and his French, were we to combine fact with fiction.

Given that Levasseur anchored his small eighteen-gun frigate La Foudre in the north lagoon, known as Gorda Sound and North Sound today, for repairs, the duel would have to be fought on one of the lagoon’s beaches. Although today there is only a significant dune presence at Savanna Bay, or as it was known in the 17th century, West Bay, there were other dune systems in the past, almost certainly some of them at the lagoon.

Hills — and a lazy lookout — would have screened the Arabella anchored to the southwest from view. Of course, Levasseur would have been advised to keep a good lookout (we know Peter Blood would have). Even so, Spanish pirates would surely have thought twice about attacking one or two stout buccaneer frigates.

Virgin Gorda in the 17th century has everything we imagine necessary for a duel on the beach between pirate captains — except coconut palms.

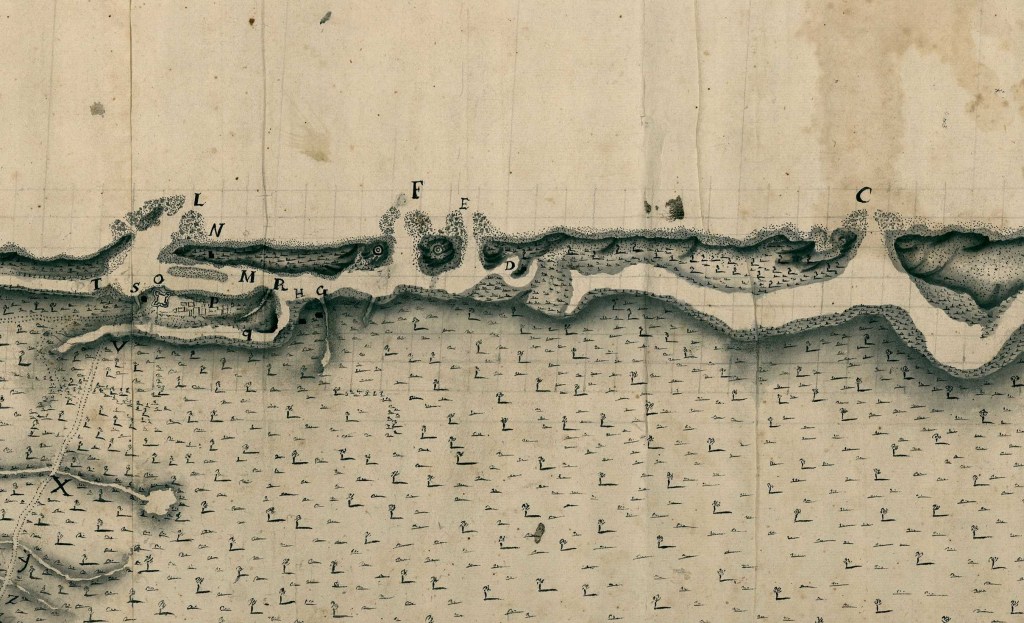

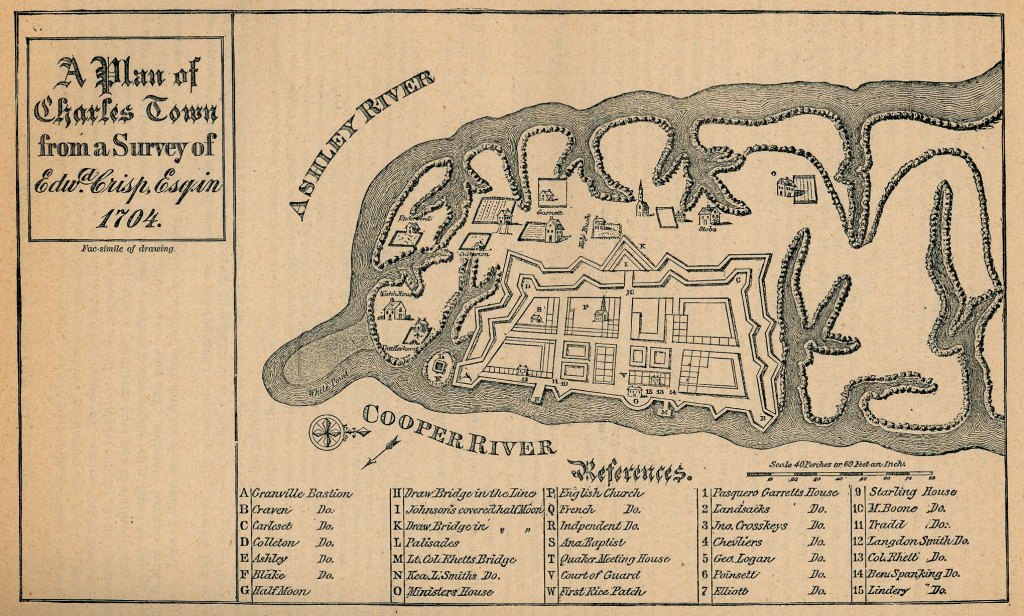

The Terrain in the Film: Three Arch Bay at Laguna Beach

The duel in the film was shot not on Catalina Island, as many fans often assume, but at Three Arch Bay at Laguna Beach. It is a classic Southern California vista: a sunny sandy shore amidst grand, craggy, evocative rocks. We will assume that the palm trees in the background were put there by the set designers and their crews, notwithstanding that Southern California (I lived in San Diego for twenty years and in LA for five) is known for its various palm trees, although the coconut is not one of them. The romantic vista adds to the scene, almost as a third character. The shot below is but one of many the beach was perfectly suited for, even demanded.

In fact, the location was chosen specifically to make the duel more exciting. From the original script by Casey Robinson: “The nature of our location will help a good deal here, for the fight not to be on the flat, but will range over the rocks and cliff edges of the rough country.”

Coincidentally, there is one location on Virgin Gorda that does look similar: “The Baths,” where sandy shore meets rock formations. It’s too far south, though, to answer the novel’s description of action and location, but following a novel closely has never stood in the way of Hollywood.

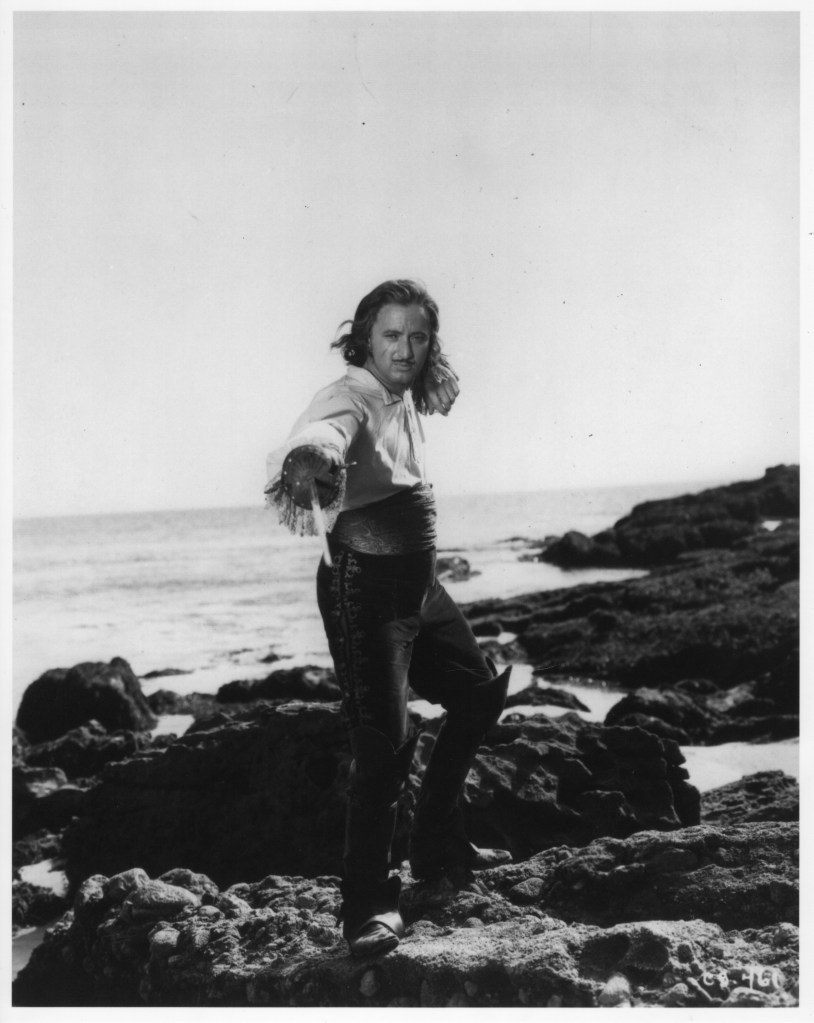

The Hero: Peter Blood

If you’ve read the novel or seen the 1935 film, you already know Peter Blood’s history: a physician (with surgical skill) accused of treason for treating a wounded rebel during the 1685 Monmouth Rebellion, he was convicted and sentenced to ten years transportation as an indentured servant at Barbados. During a Spanish raid of reprisal he and a number of his fellow rebels-convict board the Spanish frigate at anchor while the crew is indulging in pillage and rapine ashore, capture it, and destroy the Spaniards in their boats the following morning. The rebels-convict escape to Tortuga, an island just off the north coast of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti), and become buccaneers.

Given Peter Blood’s martial experience and Spanish imprisonment previous to setting down as a physician and eventually turning buccaneer, he would certainly be quite familiar with the French, Dutch, and Spanish schools of fence with thrusting weapons — the smallsword and the Spanish rapier — and also the cutlass given his Dutch naval experience, and would surely be able to handle a sword well-enough to defend himself in a variety of circumstances.

Importantly, the novel is a swashbuckling romance, with associated noble notions of duty, honor, and “right as might” rather than the opposite. These virtues set the stage for the duel in which Peter Blood rescues a swooning heroine in danger of sexual assault, a theme Sabatini often returns to in his novels and which often defines his heroes. Although swooning damsels are thankfully less popular today, the virtue of standing up for and defending the oppressed, whatever their sex and circumstances, will hopefully never go out of fashion — and likewise that Levasseurs everywhere will sooner or later get their just desserts via sword or otherwise.

A much more detailed history &c will be provided in Captain Blood: His Odyssey, the 100th Anniversary Annotated Edition later this year!

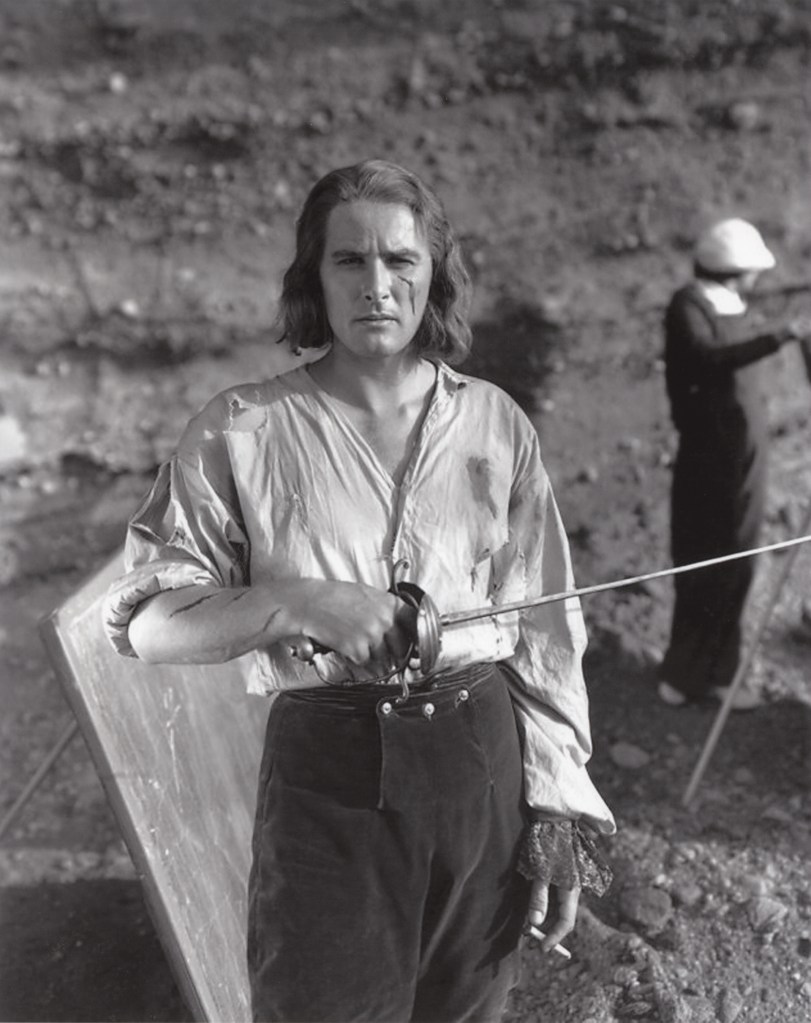

The part is played by Errol Flynn in the 1935 film. Although a bit young for the role at twenty-six — Sabatini’s hero was in his early thirties — Flynn didn’t depart too far from the character as described by the author. His dress is not quite as sartorial as Sabatini described, and Hal Wallis of Warner Bros. Studio was often incensed that Flynn even wore a lace cravat, much less anything that might be regarded as “feminine.” Wallis was reportedly furious with historical consultant for the film Dwight Franklin, and with director Curtiz for taking his advice, something I can relate to from personal experience: inevitably there’s someone in the mix, even if not the director or writers, who doesn’t like the historical consultant’s advice — an art director, for example. But Franklin was right, even though he had never seen eyewitness images of buccaneers drawn in the 1680s: some of them are wearing lace cravats!

The Fictional & Historical Villain: Captain Levasseur

The character of Levasseur, played with panache and an exaggerated French accent by Basil Rathbone, is based on two historical characters. Sabatini appropriated the name and some of the character from the real Captain François Levasseur, a Huguenot soldier of fortune, military engineer, and de facto governor of Tortuga from roughly 1640 to 1652. During his tenure he heroically repelled a major Spanish attack and despicably persecuted local Catholics in the name of Calvinism, among other crimes.

Neither the character of Levasseur nor the name was based, as a page or two on Wikipedia (far more often than not a terribly inaccurate resource on pirates and piracy, not to mention many other subjects) have stated, on the early 18th century French pirate, Olivier Levasseur aka La Buse (a nickname which might mean the “Buzzard” — the swift but proverbial stupid European bird of prey, not the American carrion eater — or “Mouth” or “Cow Dung” depending on spelling).

By his own admission, not to mention obviously, one of Sabatini’s his principal sources was Alexandre Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America, whose English and French editions were first published in the 1680s. The polylingual Sabatini read both. Each covers material the other doesn’t, and he found plenty of detail on Levasseur in the French. The real Levasseur (or Le Vasseur) was murdered by two of his closest associates — captains and companions in fortune hunting, practically family to him, according to Exquemelin — reportedly because he had raped the beautiful mistress, possibly also a slave, possibly a prostitute according to 17th century Caribbean historian Jean-Baptiste du Tertre, of one of them named Tibaut (or Thibaut). They intended to put an end to his tyranny.

Appropriate to his namesake fictional character, Levasseur was killed on the shore of Basse Terre, Tortuga at one of his warehouses by his two confreres and several of their associates: the eventual coup de grace was one or more thrusts with daggers. Perhaps his compadres killed him in part to protect Tibaut’s mistress — or perhaps just so Tibaut could keep her for himself. Reportedly just before he died Levasseur begged for a priest because he wanted to die a Catholic. Or at least du Tertre says he so pleaded.

More likely, du Tertre, a priest in anti-Reformation mode as all were, invented this to curry favor with his largely Catholic audience, not to mention keep his priestly credentials in good standing. Sabatini carried Levasseur’s unconscionable behavior over to his fictional French buccaneer who kidnaps the besotted daughter of the governor of Tortuga — his inamorata — and clearly intends to rape her if she resists his advances.

Sabatini also based the character on François l’Ollonois (or L’Ollonais as Sabatini spells it according the edition he studied), aka Jean-David Nau, &c — a vicious French buccaneer noted not only for his successes against the Spanish, but for his murder and torture of Spanish prisoners beyond that of most of his brutal brethren, few of whom would have cut the heart from a living prisoner and taken a bite from it, for example. That said, he was not the only French buccaneer to decapitate prisoners on occasion, and the torture of prisoners by buccaneers was common, horrid, and often at its worst in the search for plunder. Sabatini notes that the fictional Levasseur had learned his trade as the lieutenant of l’Ollonois.

A former indentured servant to a boucanier, l’Ollonois became a buccaneer circa 1660, rose quickly to command, and so served until his brutal and well-deserved torture and death at the hands of Native Americans on the Isthmus of Darien in 1669. His executioners burned and scattered his remains. Sabatini has clearly based the character of his Levasseur on both the original Levasseur and l’Ollonois.

The l’Ollonois lieutenant who would have been the fictional Levasseur’s historical counterpart was one of the following, or even all of them: Michel le Basque (Michel de Maristegui according to some scholars, the sieur d’Artigny according to du Tertre), a retired buccaneer and French officer who had captured a considerable Spanish prize not long before he commanded the ground force at Maracaibo in 1666, and commanded le Dauphin, l’Ollonois’s former ship, in 1668 (by now l’Ollonois commanded the Saint-Jean of 26 guns); the literate Moise Vauclin who commanded the buccaneer vice-admiral at Maracaibo, of 10 guns and 90 men; or Pierre le Picard who commanded a brigantin of 40 men at Maracaibo in 1666, separated from L’Ollonois in 1668, and guided Henry Morgan to Maracaibo in 1669. The fictional Levasseur’s previous experience at Maracaibo as L’Ollonois’ quartermaster or lieutenant would, of course, well-serve the plot of Captain Blood: His Odyssey.

One or more of these men probably also have served as the inspiration for Cahusec, the fictional Levasseur’s quartermaster (second-in-command, or lieutenant as Sabatini his it), whose name Sabatini almost certainly took from François de Rotondy, sieur de Cahuzac, who attacked the English under Edward Warner at St. Kitts (Saint-Christophe) Island in 1629 at the Battle of l’Anse-aux-Papillons.

Now that our brief exposition of history is complete, on to the actors, choreographers, and the film duel itself!

Actors as Adversaries: Errol Flynn as a Swordsman

It is common for Hollywood publicity machines to endow their stars with qualities and skills they don’t actually have, or to grossly exaggerate them, and fencing skill of swashbuckling stars, with some notable exceptions, was treated no differently.

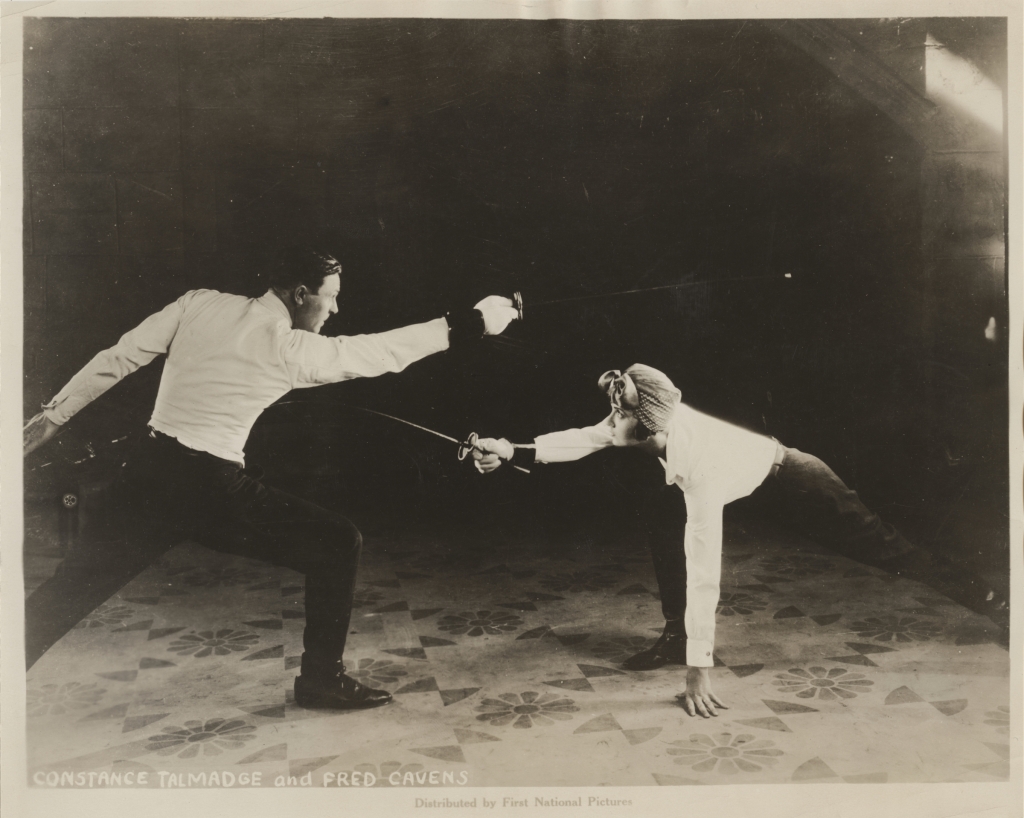

Errol Flynn has long had a reputation as a swordsman — Olivia de Havilland (Benham, 1937) said that he could fence, among his many other athletic accomplishments — but according to the film’s choreographer and fencing master Fred Cavens, not to mention Flynn himself, the swashbuckling actor was not much of a fencer, Hollywood promotional media notwithstanding. Cavens stated in 1941 that Flynn “fences execrably.” (Brady, 1941.) In fact, Cavens doubled for Flynn more than studios were willing to admit publicly. It is doubtful that Flynn knew anything about fencing prior to meeting Cavens on the set of Captain Blood.

Film historian Rudy Behlmer was more nuanced: “Flynn, on the other hand, did not have the discipline for constant practice. Fortunately, he was a quick study and a natural athlete, and this, together with his form and flair, made his duelling look good on the screen.” (Behlmer, 1965.) An accurate assessment, in my opinion.

Basil Rathbone, who played Levasseur and was in fact a skilled fencer, said that “Mr. Flynn and Mr. [Tyrone] Power were fine actors, we all know that, but they did not know swords… The only actor I actually fought with on screen was Flynn, and that’s the only time I was really scared. I wasn’t scared because he was careless, but because he didn’t know how to protect himself. I knew how to protect myself, but it’s like a professional fighter in boxing — fighting someone who doesn’t know how to fight. But sometimes the fellow doesn’t know how to fight will do something outrageous and you’ll find yourself injured. I stayed away from Flynn as much as I could, and, as he was eventually going to ‘kill’ me, it didn’t look bad on the screen.” (Jones, 1972.)

Maureen O’Hara in her autobiography ‘Tis Her wrote of her work with Flynn on Against All Flags (1952), “As you might expect, Flynn was an excellent fencer.” Even so, she also wrote, “I was flattered when critics said that I had outfenced Errol Flynn!” And so she had, being far more diligent at learning to fence from Cavens, and, as a woman actor in Hollywood, having far to prove to sexist producers and directors.

Douglas Fairbanks Jr., a swashbuckler in both film and life, also commented on Flynn’s swordplay: “‘Errol Flynn was good at staging a scene, especially in close ups, but I think he was better at other kinds of fencing,’ he added, pleased with his joke.” (Page, 1968.)

Flynn had little to say in his autobiography My Wicked Wicked Ways about his swordsmanship, perhaps because he was trying to avoid the stereotype that dogged him for so long. Even so, he admitted his lack of fencing skill:

“I don’t know much about fencing, but I know how to make it look good. You only have to stand still and look forward, your head proud, and let the sword point straight out, you and the sword both unmoving, and it is dramatic. Let the sword point dip two inches, and the gesture can look very clever and dangerous.” In fact, this is an excellent en garde with the epee de combat, or late 19th and early 20th century dueling sword, and for that matter, with rapier and smallsword as well.

In fairness to Flynn, Hollywood fencing master Ralph Faulkner (more on him below) stated that Flynn “could memorize every movement in a sword script and remember them six weeks later.” (Folkart, 1987.)

None of this lack of fencing ability stopped the Warner Bros. or other studio publicity machines from claiming otherwise. In fact, Warner Bros. in its press package claimed that Flynn was trained for Captain Blood by “Professor Guiseppe Valcori, Italian fencing expert,” whose existence no amount of research can confirm — because he’s an invention of Warner Bros. In fact, Flynn was trained for the film by Fred Cavens.

Actors as Adversaries: Basil Rathbone as a Swordsman

Basil Rathbone, on the other hand, was a skilled, albeit non-competitive fencer — a “good club fencer” in the parlance of the day, and there is no shame in this by any standard. In his autobiography In and Out of Character he notes that he studied in London under famous masters Léon Bertrand and Félix Gravé, both of them gentlemen of the traditional French school. Reading their books and articles, it is easy to see how Rathbone came by his noble, elegant form. Later he studied, for five years according to Rudy Behlmer, under Fred Cavens, in Rathbone’s words “the greatest swordsman of them all,” with additional preparation by Cavens for various films.

Occasionally one runs across a Hollywood history describing the Captain Blood duel as between two actors ignorant of fencing, but this is arrant ignorant nonsense compounded by a lack of research: by all accounts, including eyewitness and other firsthand, Rathbone was a competent fencer, if not a competitor. There is no shame in being a club fencer; many of us who were once serious competitors tire of competition and become club fencers for reasons of recreation and study — for sheer pleasure, in other words.

According to his autobiography, Rathbone took up fencing “because in the early days, when I was training for to be an actor, you went for a job on the understanding that the producer knew you could fence, that you could sing and that you could dance.” He further noted, “I enjoyed swordsmanship more than anything because is was beautiful. I thought it was a wonderful exercise, a great sport. But I would not put it under the category of sport; I would put it under the category of the arts. I think it’s tremendously skillful and very beautiful.” (Jones, 1972.) “It’s the finest exercise I’ve discovered yet, requiring speed, timing, endurance.” (Whitaker, 1936.)

Rathbone had a deserved reputation as a good fencer among the Hollywood crowd. Cavens noted that in swashbuckling films the “villains, especially Basil Rathbone, are splendid fencers, but the heroes…are ineffectual.” He further said that Rathbone was able to handle himself throughout with ease [i.e. not doubled in The Mark of Zorro].” (Brady, 1941.) Even so, he also noted that, “He has excellent form and is the most colorful of all the people I have taught. I doubt that he would do well in competition, but for picture purposes he is better than the best fencer in the world.” (Behlmer, 1965.)

Fencing master Ralph Faulker described Rathbone as an accomplished swordsman (Folkart, 1987), and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. stated that “Basil Rathbone was very good” (Page, 1968).

Long, Lean, and Lithe

One visual aspect of the duel that immediately stands out is that of two long, lean, lithe swordsmen — literally almost living swords themselves — engaged in mortal combat. Fred Cavens noted that “the ideal duelist is tall, lithe, quick on his feet, and with a nice swift coordination of of eye and muscle.” (Whitaker, 1936.) Both Flynn and Rathbone easily met this ideal.

Agesilao Greco, in his great book La Spada e la sua Disciplina d’Arte (1912), described the dueling sword — the spada or épée de combat — in terms that could apply not only to long sharp thrusting swords themselves, but to those who, with similar physical characteristics, wielded them, perfectly imagining the idealized adversaries in Captain Blood as played by Flynn and Rathbone:

“La spada è acuta, pungente, affilata, forbita, fatale, formidabile, lucida, nuda, fina, forte, ben temprata, nobile, perfetta.“

“The epee is pointed, biting, sharp, forbidding, fatal, formidable, shiny, naked, fine, strong, well-tempered, noble, perfect.” (Author’s translation.)

That said, there are outstanding fencers who are not only not long, lean, and lithe, but who appear awkward, lacking any sense of classical form. But it’s those built like Flynn and Rathbone who arguably look best in screen duels.

Fred Cavens put it best: “Film fencers should have perfect grace and form, qualities which are not necessary in competition… I have seen Olympic champions who had such atrocious form they couldn’t appear in pictures because audiences would laugh at them. But they would be extremely dangerous in a real duel.” (Behlmer, 1965.)

Flynn, and probably Rathbone as well to some degree, are also responsible for popularizing “6′ 2″ and 180 pounds” as the masculine ideal in height and weight. Fan pages and unauthorized biographies often list the height of both men as 6′ 2″ inches, although in fact both men appear to have been around 6′ 1″ tall. Flynn probably did weigh around 180 pounds. Rathbone in his autobiography gives his own weight as consistently 172 pounds (and it’s not improbable that he claimed a couple of pounds he didn’t have).

But it was Flynn who really set the ideal, thanks to a 1936 article in the Los Angeles Times: “but he [Flynn] also started a vogue for handsome young six-foot-and-over-super-huskies as leading men which hasn’t been equaled before in screen history…it began to be realized how six feet two inches and 180 pounds of 26-year-old virility could knock ’em over at the box office.” (Wolfenden, 1936.)

And so it went from there. I still recall in the 70s and 80s men trying to impress women, and even other men in locker rooms, by their purported “6′ 2″ and 180 pounds.” The fact that half of them stood an inch or two shorter than me, who’s a hair over 6′ 1″, seemed to matter not at all to them.

So engrained was this ideal that George MacDonald Fraser in his comic, occasionally satirical, novel The Pyrates (1984) made his Boy Scout-ish naval hero, Capt. Benjamin Avery, “everything that a hero of historical romance should be; he was all of Mr Sabatini’s supermen rolled into one, and he knew it… For the record, this wonder boy was six feet two, with shoulders like a navvy and the waist of a ballerina…”

Fraser didn’t forget Rathbone: “gentlemen-adventurers proud and lithe and austere and indistinguishable from Basil Rathbone…” Further, the character of “Bilbo is Basil Rathbone playing a raffish Captain Hook.” The novel is an homage to the Golden Age of piratical swashbuckling books and films of the 20s, 30s, and 40s.

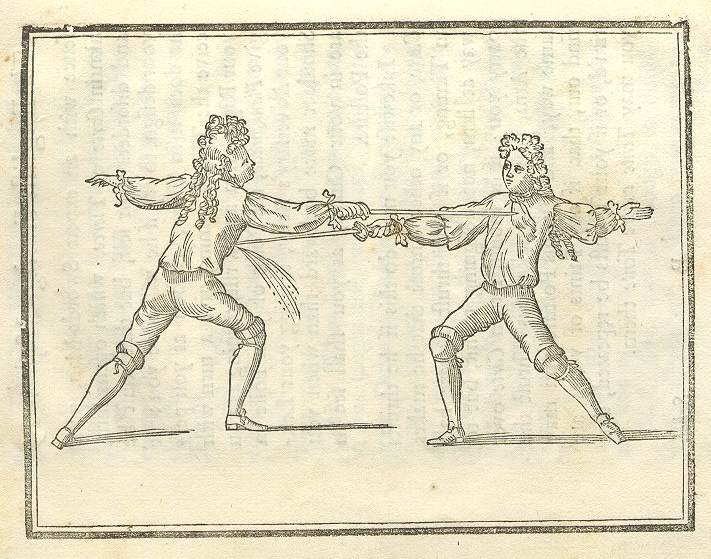

The Swords

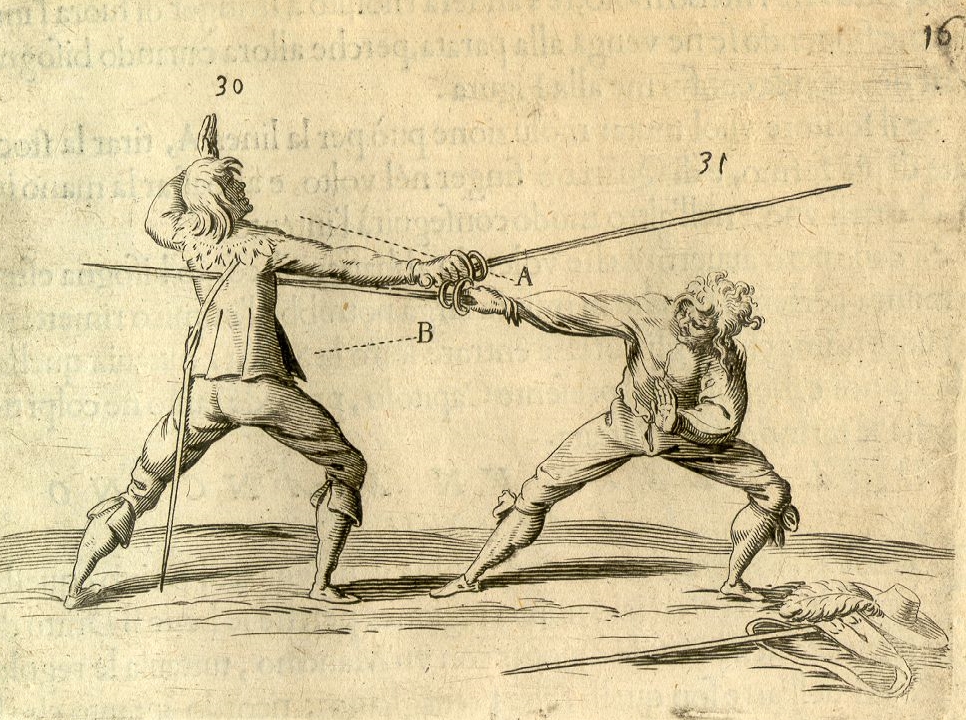

Historically, if thrusting swords were used in a late 17th century duel among the English and Europeans other than the Spanish, Portuguese, and some Italians, they would usually have been smallswords with double-edged flat or hexagonal (or similar) rapier-like blades in form but shorter, or three-cornered blades, including Colichemarde blades quite broad at the forte. We can’t rule out an occasional “transitional rapier” (a modern term) with perhaps longer blades and possibly larger hilts. At least one was recovered from the Sedgemoor battlefield in 1685 (which battle plays a great role in the novel and film), probably dating 1640 to 1660.

Sabatini describes long rapiers as being used, and probably intended Spanish cup-hilts or transitional rapiers. However, the term was also used as slang for smallsword in the late 17th century, given that both swords were used for thrusting, so it could still be correct to say that “rapiers” were used. Historically, however, cutlasses would have most often been used (more on this in part five).

In the film, both swords are theatrical “rapiers” mounted with sport epee blades, known in the past as “hollow,” three-cornered, or triangular blades. They are stiffer by comparison to foil and saber blades, and show up well on screen. The hilts of both swords used in the film duel are a bit fanciful, neither corresponding exactly to historical swords. Flynn’s appears to something of a reduced Pappenheimer hilt (for example, a Norman type 67 but with no side rings), with two solid shells, a pair of curved quillons, and a knuckle guard, perhaps also resembling a shallow Spanish bilbo-hilt (Norman type 82) with smaller shells.

Rathbone’s rapier hilt appears to be nothing more than a common smallsword hilt (Norman type 112) but with enlarged shells, rings, and quillons. One might argue it is instead a small-hilted Spanish “dueling rapier” or “Spanish smallsword” (as some call it) — an espadín — of a sort that was introduced 1680 to 1700 and became even more common after a Bourbon began sitting on the Spanish throne. Most of these have large (as compared to French smallswords) rounded shells, or smaller, shallow cup-hilts, or smaller “bilbo” hilts, but occasionally one with large mostly flat shells, as with Rathbone’s, is seen. Perhaps a bretteur or spadassin (a thug with a sword), as Levasseur clearly was, preferred the longer blade of the transitional rapier or espadín to that of French smallsword in order to gain an advantage. That said, the heavier transitional rapier and Spanish smallswords would be at a disadvantage in speed as compared to the true smallsword.

The sword designer — Fred Cavens, perhaps, or more likely pirate historian and costume designer Dwight Franklin — was probably thinking of swords that would evoke “Cavalier” or “Musketeer” rapiers of some sort.

The enlarged hilts of the theatrical rapiers used provided a better film image, or so the thinking probably went, than the smaller, but more legitimate, authentic smallsword hilts. Plus, viewers have been conditioned by fiction and film to expect rapiers no matter the era, no matter how anachronistic. For filming, the larger rubber buttons or points d’arrêt were removed — more on this below!

Choreographer & Choreography

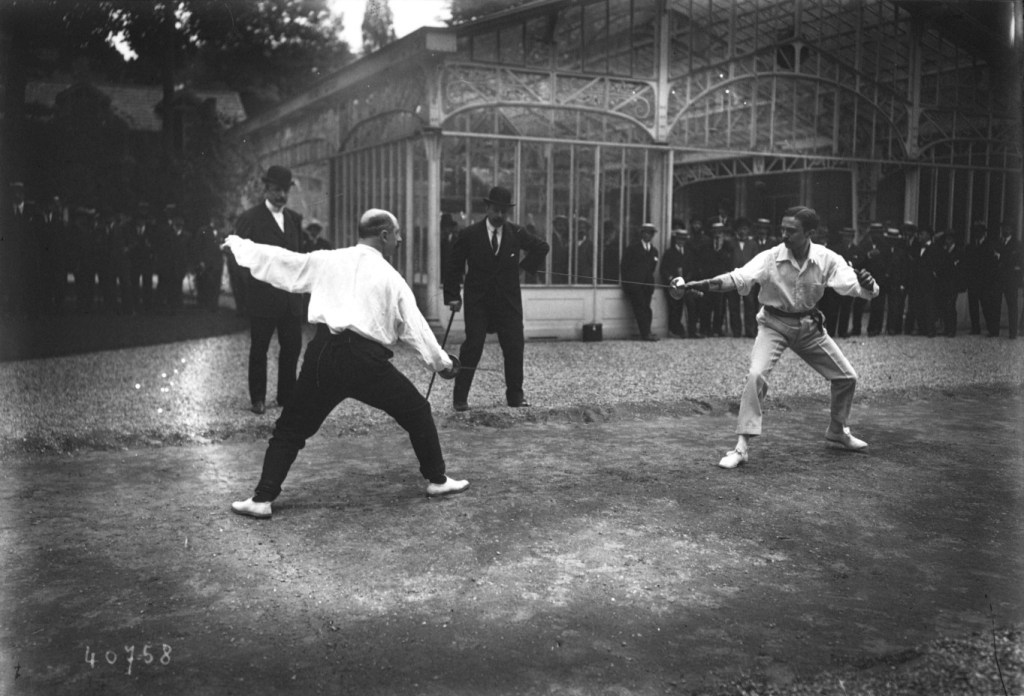

The duel was choreographed by famous swordfight director Fred Cavens. He began fencing at twelve years old circa 1894, was teaching other boys how to fence at fourteen, and graduated at eighteen from the famous L’École Normale de Gymnastique et d’Escrime Militaires de Belgique in Brussels, a school modeled on the famous French military school at Joinville-le-Pont near Paris. At twenty-one he was a full-fledged fencing master in the Belgian army.

After his service in the Belgian Army, Cavens emigrated to the US in 1919, soon after both his marriage to a Belgian dancer in an opera company and the end of World War One. He was invited by some American sportsmen, fencers we assume, to open a salle in Santa Barbara, California, leading to an introduction to various film studios, whose swordplay on camera to date, other than that choreographed by fellow Belgian master Henry J. Uyttenhove, was often little more than knife-sharpening actions, often in long shots, or was entirely doubled (which generally demanded long shots in order to carry out the deception). (Anon., 1936.)

Cavens got his start in Hollywood choreographing the swordplay for the 1922 short film The Three Must-Get-Theres, a parody of Douglas Fairbanks’s 1921 The Three Musketeers. The comic film is quite funny, even brilliant at times, and is possibly the best send-up of swordplay and musketeers I’ve seen. Although there are moments of common “blade sharpening” fake swordplay, most of the fencing is of outstanding caliber. In fact, director and star Max Linder was an accomplished fencer who had competed in epee, if not also in foil and saber. The film, by the way, is available on YouTube in a couple of versions, and also on a Grapevine DVD. The latter is by far the better version.

Fairbanks loved the swordplay in the comic film and first met Cavens on the set of Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall, a production starring Fairbanks’s wife Mary Pickford. Fairbanks quickly hired him for Don Q, Son of Zorro (1925) and then for his genre-establishing 1926 swashbuckler The Black Pirate the following year. Cavens also choreographed the swordplay in Fairbanks’s The Man in the Iron Mask (1929). (Behlmer, 1965.)

Cavens had a theory of romantic realism — a bit more romance, a bit less realism, with authentic if at times theatrical fencing — for filming swordplay on the screen, a theory that worked quite well in practice from the audience’s perspective.

“For the screen, in order to be well photographed and also grasped by the audience, all swordplay should be so telegraphed with emphases that the audience will see what’s coming.” (Behlmer, 1965.) This, of course, is a form of false tempo, discussed here, that would likely get a fencer killed in a duel. But it works well for the audience — and that’s the goal.

Behlmer further quoted Cavens: “All movements — instead of being as small as possible, as in competitive fencing — must be large, but nevertheless correct. Magnified, is the word. The routine — there must be a routine, and so well learned the actor executes it subconsciously — should contain the most spectacular attacks and parries it is possible to execute while remaining logical to the situation. In other words, the duel should be a fight and not a fencing exhibition, and should disregard at times classically correct guards and lunges. The attitudes arising naturally out of fighting instinct should predominate. When this occurs the whole performance will leave an impression of strength, skill and manly grace.”

Cavens prepared actors, ranging from Flynn and Rathbone to Maureen O’Hara, Binnie Barnes, Jean Peters, and many others, thoroughly, teaching them not only the scripted swordplay itself, but also fencing in general. Maureen O’Hara in her autobiography described her preparation for At Sword’s Point (1952): “I trained rigorously for six weeks with Fred Cavens and his son to perfect my stunts for the picture. Fred Cavens was an outstanding Belgian military fencing master and had trained all the great swashbucklers in Hollywood. He taught me intricate attacks and parries, envelopments, disengagements, and coupes. Physically, I’ve never worked harder for a role.” For The Corsican Brothers (1941), Cavens coached Douglas Fairbanks Jr. for a month prior to filming. (Brady, 1941.)

His process was described by Thomas Brady: “Cavens’s greatest value to a producer is his ability to prepare a fight with the precision of a choreographer. No impromptu bout, he says, looks truly exciting to the camera. His technique with a picture follows a regular pattern. First, with the director and the camera man, he examines the sets to be used for fights and learns in general what the action must be and how much time it shall take. Then, in the esoteric language of the swordsman he writes down every move the attacking fencer will make. For a three-minute fight in Fox’s “The Mark of Zorro,” Cavens’s “score” ran to 750 words. Tyrone Power and Basil Rathbone had to memorize it… Even when Cavens and his own son fight a duel on the screen, as in “The Corsican Brothers,” they memorize a “ballet” routine beforehand.” (Brady, 1941.)

The Duel Master Scene in the shooting script by Casey Robinson includes the following notes, which depart from Sabatini for whom Levasseur was a mere thug and bully in both his life and his swordsmanship:

“The details of this duel must naturally, be worked out by an expert in this line. We wish to emphasize here the general nature that this fight must have. Usually duels in pictures are contests between some agile, brilliant, hero and a slow and dull witted, even though powerful villain. Such is not the case here. Here we must have a great fight between two truly great swordsmen, equally matched in quickness, brilliance, and skill. It is not a fight to the first advantage or the first spilling of blood, but a fight to the death. It is a vicious, terrific battle in which both men take a great deal of punishment before the final conclusion. In other words, the fight would be routined not after the order of duels that have been shown in pictures, but rather after the order of some of the great rough and tumble encounters that have made their pictures famous notably, the fight in “The Spoilers”. Thus, before the battle is finished, part of Blood’s clothes have been cut away and he is very much marked up by Levasseur’s sword.”

Note that dueling was still in vogue in France, Italy, and Hungary at the time of filming (although WWI had diminished the practice significantly, WWII would almost entirely put a stop to it), thus the comments on first advantage and first blood have more than purely Hollywood relevance. In fact, my first fencing master, an active swordsman during the 1930s and trained by the famous Italo Santelli, had fought at least one duel in Budapest in the 1930s. Fred Cavens had acted as directeur de combat for several duels and had fought as many more. (Anon., 1934.)

[Quick aside: until a couple or so decades ago, referees in modern fencing in the US were referred to as directors, from directeur de combat, the person who supervised a formal duel. If the competition were non-electric, the director might be referred to as the President of the Jury, for the president presided over four judges. Today, the term “referee” is used, the powers-that-be rather incredulously arguing that the name change would make fencing more accessible to the still largely imaginary audience. “One fool makes many,” according to the proverb.]

According to the LA Times, Cavens also trained “one hundred fifty men…in the art of being pirates at the Warner Studio” for Captain Blood. “They go to school every day for eight hours to fence under the tutelage of Fred Cavens… He is also teaching them how to climb riggings and other tricks of the trade.” (Kendall, 1935.) Certainly Cavens would have trained the pirates in cutlass-play, but as for teaching “pirates” to climb aloft, although Cavens would certainly know how this was done given his experience on Douglas Fairbanks’s The Black Pirate (1926), we imagine Sailor Vincent (see below) or some other salty seafarer was actually responsible for this aspect of training.

Filming the Duel

Shooting a duel could take days, and one author (Matzen, 2010) notes that shooting this one was hindered by “bad weather, milky gray skies, [and] audio challenges brought on by the pounding surf,” and two actors who could not fence — in fact, it was only Flynn who could not fence. The Virgin Magra scenes, including the “pearls before swine” build up to the duel, were shot September 16 through 18 and 24 through 26, with delays caused by cloud cover, aircraft, and high fog. Some takes were shot with artificial light (Florczak, 2022).

“These scenes take, Lord knows, how many set-ups. For instance, they will not take a long shot alone; they’ll take a master shot, then a medium shot and then take some close-ups. Any fight that lasts five minutes on the screen could easily take two days to shoot,” said Basil Rathbone (Jones, 1972).

According to Rudy Behlmer (1965), “When the duel is shown to the director, he, and perhaps the cinematographer, may alter the set, props and lighting. After which, the duel routine is broken up into master shots, close-ups, special angles, etc., and photographed with either principals or doubles, depending upon the actors’ capabilities and the specific shot.

There is a myth that director Michael Curtiz engaged in swordplay himself during the filming: “Curtiz, who is quite the swordsman himself, having been a member of the Hungarian Olympic team in 1912, would fight with each of them first, to show how he wanted it done.” (Whitaker, 1936.)

This of course, is nonsense, at least regarding the Olympic Games, and probably in its entirety as well. Curtiz, although apparently fond of claiming he was on the 1912 Hungarian team, does not appear to been an Olympian. I have not found his Hungarian names (Manó Kertész Kaminer and Kertész Mihály) or anything similar among the fully detailed records of the foil, epee, and saber events from first pools to final of the 1912 Games. Even so, numerous biographies repeat the myth as fact, although occasionally the word “allegedly” is used. For good reason did Cavens, not Curtiz, choreograph the duel.

Doubling of the sword-fighting actors was common at the time, including in Captain Blood. “The villains, especially Basil Rathbone, are splendid fencers, but the heroes, according to Mr. Cavens, are ineffectual fellows when it comes to cold steel… And when the script demands that he [Errol Flynn] resort to the sword to defend his honor, Warner Brothers resorts to Mr. Cavens.” (Brady, 1941.)

However, Fred Cavens, as proved by the photo below, as well as others farther down, doubled Rathbone, not Flynn, when necessary during the duel. In fact, Hal Wallis complained of the dailies of the duel, noting that the wigs and costumes of the doubles were terrible as compared to those of the actors. The photos below show he had good reason. Thankfully, the doubles were used only in the long shots, as far as I can tell, in the final cut.

Flynn was doubled as necessary by Caven’s assistant, Ralph Faulkner, soon to become one of Cavens’s principal Hollywood heirs. Faulkner had been a member of the US Olympic saber team at the 1932 Games: “One of the mysteries in the competition between Poland and the United States was the removal of Ralph Faulkner, the only Southern Californian on the team, from the American line-up. Faulkner had been entered in the contest with Hungary and had succeeded in taking two of the three bouts for America in her score against that country.” (Durbin, 1932.)

A mystery indeed! [And a brief digression!] The Hungarians ruled saber for fifty years; their national saber championship was tougher than the Games themselves, so deep were the Hungarians in elite sabreurs. That Faulkner could win two of three bouts against the Hungarian team that would win gold is amazing — no other fencer at the 1932 Games won more than one bout against them (in fact, for fifty years a total of slightly more than 30 Hungarian sabreurs won nearly every elite competition in the world) — and should have guaranteed his inclusion in the bronze medal bout against Poland. However, the elitist East Coast prejudice against his Southern California roots is not out of the question, and this probably cost the US a medal: the US lost to Poland by a single touch.

One of the methods of excluding “outsiders” was via cheating by side judges and bout directors during championships: the director had one and a half votes, and each of the two side judges watching a single fencer had one vote each and could therefore overrule even an honest director. The other method, common in the first half of the 20th century, was exclusion by the committee “choosing the best fencers” or even by a team captain during events. I’m speculating, of course, but these latter two means were probably the way Faulkner, an outsider, was excluded from the bronze medal match — and entirely from the individual events in the 1928 and 1932 Games.

[Warning: further fascinating digression ahead!] In fact, until the 1950s team selection in US saber fencing was reportedly largely ruled by the “New York saber Mafia,” as many non-New York fencers called the narrow-minded, cliquish US saber fencing establishment, and a number of deserving fencers failed to make the US team due to prejudice against them, including at times of race and religion. The brilliant Herb Spector, described by one of my masters as the best saber fencer in the world in a two-touch bout, springs immediately to mind, among others. I have both met and fenced Herb: he was the personification of the highest praise of Dr. Francis Zold, my first fencing master, that of being both a gentleman and swordsman. This unsportsmanlike, even dishonorable, practice arguably had its roots in the at-the-time elitist Fencers Club of New York. (The Fencers Club of NY still exists, although some suggest that its past arrogant elitism may have passed into the hands of the New York Athletic Club. Please note that no suggestion of dishonorable or unsportsmanlike conduct is herein made toward either club today, in part because I don’t like wasting my time with NY lawyers, or any lawyers, although the sense of elitism, for good and bad, remains according to some observers.)

Faulkner himself confirmed bias as the reason he was only permitted to compete as part of the US Olympic saber team in both 1928 and 1932, and not in the individual saber events: the controlling Eastern Establishment “didn’t feel a savage from out West could be superior.” (Folkart, 1987.)

The “Mafia’s” spine, at least in regard to the Olympic Games, was broken when Hungarian gold medalist saber fencers, including one of my own masters, Dr. Eugene Hamori, emigrated to the US after the Soviet Union brutally crushed the Hungarian uprising in 1956 during the Olympic Games. The Hungarians’ technique was so superior and clean that any cheating against them would have been far too obvious.

And if this clear superiority didn’t stop the mischief, I’ve seen how some of these Hungarians dealt with cheating directors and side judges clearly in cahoots with the opposing fencer: they would drop the opponent to the strip with a welting chest cut, making the hit overtly clear even to the most willfully blind. (I’ve also seen the technique used once by a Hungarian Olympic medalist in New Orleans frustrated with the director, a friend of his — and the fencer he dropped to the ground was also a friend. Temper, temper…)

However, even as late as the 1970s the “Mafia’s” influence was still apparent to some degree, at least in the Junior Olympics, according to several fencers I knew. As a friend of mine noted at the time, he could beat any of his fellow elite junior New York competitors anywhere in the US and world — except in New York City. A bout director there even shrugged in apology to him once, after the two side judges were repeatedly, and clearly deliberately, blind to his clean touches made with undisputed priority.

Faulkner was still teaching fencing at his salle, Falcon Studios, aka the Faulkner School of Fencing, in Hollywood, when I first started learning in 1977. By then he gave lessons seated and was nearly blind, or so I was told, but his lessons were still extraordinarily instructive in blade-work. I was advised to take a lesson just to say I had, if nothing more, but never managed to do so in part because I was well-satisfied with my own swashbuckling master, Dr. Francis Zold. (I was also a college student in LA without a car.) Many Hollywood and stage fencing choreographers — Anthony De Longis comes quickly to mind — studied under Faulkner and by their own admissions owe much to him. Maestro Faulkner died in 1985 at the age of ninety-five.

But back to the filming of the duel! Flynn was noted in the production of later films as having a drinking problem on set, which in the case of swordplay would be quite dangerous.

Whether Flynn drank during the filming of the duel in Captain Blood is not noted anywhere I can find. According to Maureen O’Hara in her autobiography, “I enjoyed working with Errol because he was a pro. He always came to work prepared. He rehearsed hard and practiced his fencing sequences very meticulously with Fred Cavens… He also knew his lines, something I greatly respect in an actor. Of course, there was one glaring inconsistency with his professionalism. Errol also drank on the set, something I greatly disliked. You couldn’t stop him; Errol did whatever he liked. If the director prohibited alcohol on the set, then Errol would inject oranges with booze and eat them during breaks. We worked around his drinking. Everything good that we got on film was shot early in the day. He started gulping his “water” early in the morning and by four P.M. was in no shape to continue filming.”

Flynn himself describes in his autobiography how when filming a boarding scene during the production of Captain Blood he fell to the ground with an attack of malaria or blackwater fever. He cured the shaking, shivering weakness of the attack with a bottle of Cognac suggested, he says, by the crew. He was called on the carpet by Jack Warner the following day as the result of this drinking: “The script girl tipped me off. They had rushes of the scene I finished after the bottle of cognac. In the film I was waving the sword about like a Cossack, shouting lines that weren’t in the script, and had almost fallen off the boat. A bit of real drunken acting.”

The filming of the duel was publicized in small ways in advance of the movie’s release. The press package claimed, for example, that “Actor Breaks Three Rapiers in Duel,” which is probably true in reference to blades. Hilts might break, but are generally much sturdier. It would be surprising if spare rapiers and blades were not on set during filming. Even so, according to a press clipping, a “rush order for additional rapiers was sent out when Errol Flynn…broke three of them during the filming of scenes in which he has a duel with a rival pirate…”

Also according to the Warner Bros. publicity package for the film and often repeated as fact, Flynn “received two small wounds during his battle with Basil Rathbone.” A separate publicity clip for newspaper release noted four: the “most serious wound was on the actor’s head, slightly above the left temple. He also was cut by his opponent, Basil Rathbone, near the right eye, on the neck and on the right forearm.”

And according to one reporter, “they really drew blood too, so that Flynn had some actual wounds to be doctored after that exciting buccaneering day.” (Whitaker, 1936.)

Although injuries do occur on occasion in well-prepared, well-choreographed swordfights, those listed here are probably pure invention for the sake of publicity: Rathbone in his autobiography states that he never hurt anyone when filming any fencing scene, nor was hurt by anyone. The photograph of Flynn below shows the “wounds” — and they appear to be nothing more than those created by a make-up artist for the scene. If Flynn were wounded during the filming of the duel, it would have therefore been by Fred Cavens, and surely due to Flynn’s own error. I think it also possible but highly unlikely that Cavens would have deliberately hit Flynn as a reminder to be careful — or not to do anything too stupid or too dangerous that might hurt his film adversary. (This can, however, be an effective teaching method with a blunt tip used during an egregious error made by a student without a jacket, although not all students are suitable to this practice.)

At one point, again according to the press package, Flynn fell off a cliff at Three Arch Bay during filming:

“Flynn was doing a scene depicting a duel with rapiers between himself as Pirate Blood and Basil Rathbone, who portrays the role of Levasseur, French buccaneer and Blood’s rival. In order to give the scene added drama, Director Michael Curtiz had Flynn drive Rathbone at swordspoint onto a small ledge on the side of a cliff overlooking the bay. The cliff was not quite perpendicular, however, sloping off gently so that the ledge was about ten or twelve feet shoreward and forty feet above the water line.

“With the cameras grinding, Flynn backed Rathbone onto the ledge according to instructions. For several minutes the rapiers of the duelists flashed. Then, suddenly, a shout of dismay rose.

“Flynn had tripped on a small rock and toppled outward from the ledge. Slowly at first, he strove to regain his footing, but in vain. When he finally realized there was no chance of saving himself, he put all his power into an outward leap. He soared out from the ledge, cut cleanly into the water, missing the base of the cliff a mere matter of inches. He swam to the beach unaided.

“A less powerful man than Flynn could not possibly have put the force behind his leap to clear the base of the cliff… [He] suffered nothing worse than a slightly lacerated knee which scraped a submerged rock.” Although it’s entirely possible that the incident did take place, Hollywood clearly does love hyperbole, not only for the sake of publicity, but for its own sake. Flynn even reportedly “rescued” Olivia de Havilland after a wave swept her into the ocean (Amburn, 2018). Separating fact from fiction is Hollywood is difficult, and fans often prefer the fantasy.

The shooting of the duel wrapped up near dusk on the final day (probably September 26). Rathbone tells an anecdote (Jones, 1972) about how “Sailor Vincent,” the nominal head of the pirate extras and, according to the press package, an “all-Navy welterweight boxing champion,” asked Flynn and Rathbone near the end of a day’s shooting if they were going to wrap it up that day or give the extras another day to get paid. “Our reputations as swordsmen were at stake,” Rathbone said, and so they decided to finish the shooting that day. They were probably quite ready to get past the exhausting shooting of the duel.

“Now what we had to do was this:” Rathbone said, “a man stood with a stopwatch, and he timed the waves coming in. There was a short routine in which Flynn had to get me, kill me, and I had to fall exactly as a wave was coming in. If I fell exactly as a wave was coming it, it would cover me with water and as it went back out again, there I would be lying on the ground with my eyes wide open. You try lying with your eyes wide open, and sea water in them without blinking. Well, we did it! Exactly to the second, we timed the swordplay which took fifteen seconds. At the end of fifteen seconds I had to fall and the wave had to come in and I had to fall into the wave. This happened exactly to the second.

“The thing that Flynn and I expected was that Sailor Vincent would come across and say, “Well, thanks for nothing!” Instead of that, all the extras applauded loudly. They were so thrilled at the sheer skill of it because this required beautiful timing and Flynn and I worked very hard on the sequence.”

After a few more shots, and with the sun soon too low at 4:30 to shoot, filming of the duel finished and everyone went home. Rathbone noted that had they failed to get the final scene correct, they would have had to shoot again the next day because he would have had to wait for a new, dry costume.

The Myth of “Sharp Tips” Used in the Film Duel

There has long been a myth that director Michael Curtiz demanded that the tips be removed from the rapiers so they wouldn’t show up on film, and therefore the actors fought their duel with sharp points. This myth, among other issues, demonstrates a lack of understanding of how practice fencing swords are constructed and used.

The rapiers used in the duel were mounted with “dry” (i.e. non-electrical — electrical scoring was introduced the following year at the Olympic Games) epee blades, which might be considered a reasonable facsimile of the “three cornered” blades of many smallswords of the 1680s. Unlike modern epee blades, which are wider at the forte (the third nearest the hilt) and thicker at the foible (the third nearest the point), epee blades for most of the 20th century tended be narrower at both forte and foible than modern blades.

Practice dry epee blades were not, and are not, sharp, but instead are forged with a flat tack-like tip, often only slightly larger in diameter than the distal end of the blade. For “dry” practice in the 1930s (which was nearly all practice back then) either a hard rubber “button” was placed over the flat tip, or a point d’arrêt with three small sharp points was lashed to it with linen thread, dental floss, or very narrow (1/16″) cloth tape. There was no sharp point beneath. See the image below.

For shooting a duel scene in any film of the era, the rubber buttons or other points d’arrêt were typically removed, leaving the flat tips which made for better visuals. The flat tips are not as obvious on film but still could be dangerous, to eyes in particular, and required well-rehearsed actors for safety. The flat tips could also scratch or even make shallow cuts in the worst cases, but were not a significant threat to life or limb except, as just noted, to eyes. Typically only a wound from a broken blade might be life threatening.

However, according to some sources citing cameraman Hal Mohr (Davis, 1971, for example), the tips of the blades were broken off at Curtiz’s demand, leaving sharp points. This not only strains belief but is easily disproven. Breaking a fencing blade is relatively easy but breaking it immediately behind the flat tip is not. It would usually require a strong cutting tool or a hacksaw blade to cut the blade just behind the tip, and would indeed leave a much more dangerous point, something no fencing master would permit in the hands of even a talented amateur such as Rathbone, much less an unskilled fencer like Flynn.

I once choreographed and engaged in some fencing with sharp, pointed scimitars for a documentary. For safety it was necessary that both of us were highly skilled with pointed and edged weapons, we rehearsed and memorized the routine thoroughly beforehand, and during actual filming we worked at about half the speed we were capable of. Anything else with sharp or pointed swords could easily have led to serious injury or fatality.

Notably, of the many original still photographs of the Flynn-Rathbone duel in my collection, at least of those in which the points are in focus, none show sharp or broken points, but instead, as expected, the typical flat points of practice epee blades. See below, for example. The photographs of the duel were taken at various stages of the its filming. The flat tips can even be seen in some of the scenes on film when watched frame-by-frame. Further, it is hard to believe that if Rathbone and Flynn had fenced with sharp points, Rathbone would not have mentioned such a dangerous undertaking in interviews or his autobiography. Again, we have a myth promoted by the Warner Bros. publicity machine and accepted at face value by much of the public.

The Musical Accompaniment

The film score was composed by Erich Wolfgang Korngold, who largely created the modern practice of classical composition for film music. Korngold reportedly had only three weeks to compose it, and was assisted by orchestrator Hugo Friedhofer. Nearly all of the film’s music is original, with one major exception and a few minor associated additions. In addition, two minor pieces — songs sung by Spanish soldiers and seamen — were composed by Milan Roder.

The major exception, of course, was the score for the duel on the beach. Reportedly, the film’s preview had been moved up and the score had to be completed within twenty-four hours. Out of time, Korngold adapted Frans Liszt’s symphonic poem Prometheus to the duel, a circumstance that apparently offended his sense of artistry and professionalism. It also led him to refuse to have the credits list him as composer, and instead as musical arranger, in spite of his having composed the majority of the film score. For this reason the score was not nominated for an Academy Award, sadly. Korngold’s original film compositions — “opera without words” and “symphonic poems” — and method of scoring changed Hollywood film music forever.

According to Brendan G. Carroll, Korngold gave Friedhofer the Liszt score along with a new introduction and coda at 8:30 PM the day before it was required. Friedhofer spent the night arranging the adaptation. At 7:00 AM a messenger picked up the orchestration for copying. It was recorded that afternoon. That said, elements of the Liszt’s Prometheus also appear in the tracks “Peter is Bound — Pirates!” and “A Timely Interruption,” the latter of which is really a continuation of the former.

The 2001 Tsunami Captain Blood soundtrack (TSU 0141) above is the only one I’m aware of with the entire film score, including the duel. The thirty-one tracks provide an hour’s worth of neo-romantic swashbuckling listening pleasure. Out-of-print and now often listed at high prices by vendors hoping to make a quick extra buck, if you’re patient you can usually find a reasonably-priced copy. It’s my favorite of all the vinyl and CD Captain Blood soundtracks, and probably my favorite of all the full swashbuckler scores available on CD (or whatever else soundtracks are published via these days — I’ve never stopped listening to and collecting vinyl and CDs even as I’ve added other media to our collection, although I did long ago abandon cassette tapes).

Liszt’s Prometheus is also excellent listening. It’s often included on collections with Liszt’s Preludes, in which case you can also enjoy the overture to the old Flash Gordon film serial, a “space opera” — which was by definition a Western set in outer space. Our most popular modern version, arguably of both space operas and Westerns, is Star Wars and its many serializations. Star Wars has also taken over most of the old classic swashbuckling genres, to my dismay.

The Duel!

And now the duel itself. The best way to enjoy it — in fact, the only way — is to watch it. For those with an interest in the actual fencing details of the choreography, I’ve included a few annotations below. Fencing enthusiasts, feel free to disagree with my observations and assessments!

The fight really was between two true adventurers. Flynn was an Irish-Australian born and raised in Tasmania. In his autobiography describes himself in his youth as a “devil in boy’s clothing,” and after numerous misadventures leading to his eighteenth year he entered several years of seafaring adventure and fortune hunting — tobacco planting, gold mining, and various sea trades — associated with Papua New Guinea. An athlete but never a fencer, he does fondly describe playing with a sword an ancestor had taken from Captain William Bligh during the infamous mutiny, and he denounces his father for giving it away to the Naval and Military Club at Hobart.

Rathbone was the Patrols Officer of the Second Battalion of the Liverpool Scottish during WWI, and was awarded the Military Cross for heroism for his intelligence collection patrols, in particular one in which he led a small party across “No Man’s Land” into the German trenches for intelligence during daylight. At one point Baron von Richtofen, better known as the Red Baron, and his Flying Circus, which included future Nazi leader and convicted war criminal Hermann Goerring, flew a mere one hundred feet overhead, strafing the British line. In the enemy trenches, Rathbone, using his service revolver, shot and killed a German soldier. Documents taken from the soldier’s pockets indicated that a retreat was imminent. Rathbone led his men out safely under heavy machinegun fire. (Rathbone, 1962.)

The duel could not have been easy to film and fight in the sand, a surface which presents its own special difficulties. The rear foot tends to slip on the lunge. Turning the foot onto its inner edge is helpful (as some 17th and 18th century masters note), as is pushing more outward than directly behind on the lunge with the rear foot, as is maneuvering the fight onto the area of wet compacted beach between the soft dry sand above and the wet saturated sand below, or onto an area of vegetation. But at least the implausible “pirate boots” — buccaneers and pirates didn’t wear them unless on horseback — would keep sand out!

The duel begins with Flynn wearing what at first appears to be a sleeveless waistcoat but is in fact a coat with different-colored sleevesl or long-sleeved waistcoat, with a baldric worn over a sash, apparently sewn or otherwise un-historically attached to the sash to keep the former from bouncing around. Rathbone is in his shirtsleeves, but likewise with a baldric worn over a sash. Eyewitness images of buccaneers in the 1680s — the only eyewitness images of any European-derived sea rovers during the Golden Age of Piracy — do show sashes on French buccaneers, but not baldrics. Sword-belts were worn instead, given their convenience, and they’re also not as hot. If a baldric were worn, it would typically have been worn beneath a sash to prevent it from bouncing around. (Why baldrics over sashes rather than under them as more practical? So they baldrics could be removed while leaving the romantic sashes in place.) I’ll discuss this further in part five of this series.

And now, for fun, a brief look at some of the swordplay itself. One of these days I may annotate the entire duel, but I’ve lost my old notes and haven’t the time at the moment to review it in its entirely again. A few instances will suffice for now.

The duel begins as several of Peter Blood’s officers begin escorting Arabella Bishop to a small bluff en route to their ship. Cahusec tries to restrain Levasseur but he’ll have none of it. “You do not take her while I live!” he shouts and draws his sword. “Then I’ll take her when you’re dead!” Blood replies, drawing his own sword, tossing his hat, and beginning to remove his baldric and waistcoat. Cahusec tries one more time to dissuade his captain, but fails.

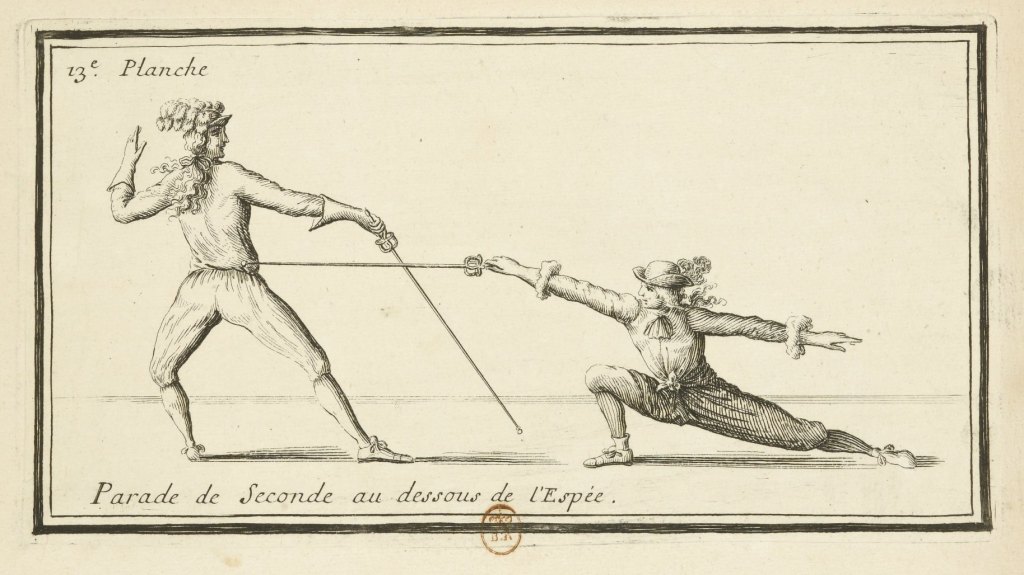

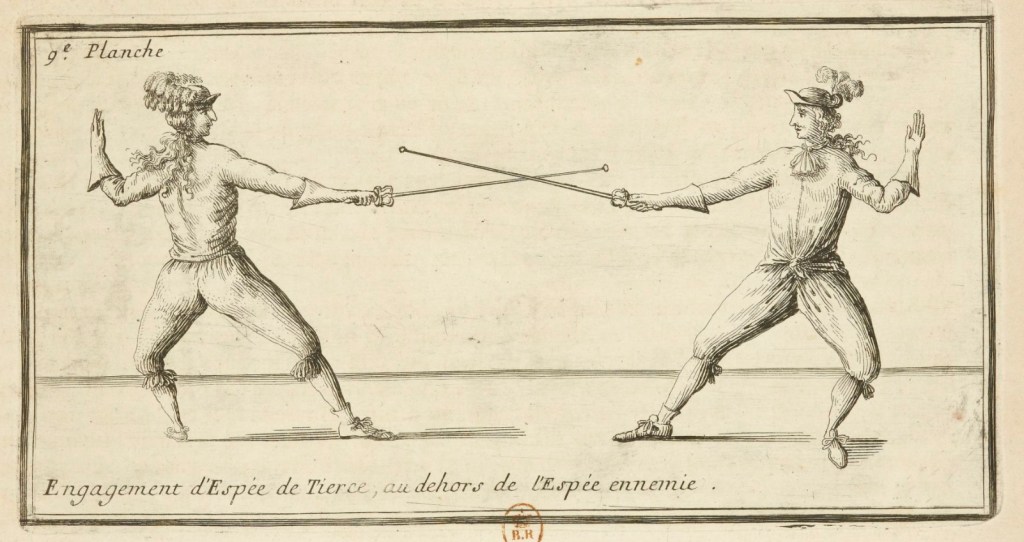

Levasseur runs at Blood and thrusts in tierce. Blood parries tierce and shifts aside for additional protection against the the attack. The men move to open ground where Levasseur makes a half lunge, thrusting in quarte. Returning to his guard, Levasseur makes several change beats from quarte to tierce and back, followed by a few disengages in the same line against Blood’s en garde in quarte.

Levasseur feints outside (tierce), then inside (quarte), and finishes with a thrust without lunging in the low line, which is parried quinte (low quarte) by Blood, who ripostes with a quick extension but no lunge. Both men are clearly engaging in reconnaissance.

Now, in a wide shot, Blood traverses to his left. Levasseur attempts a wide, too obvious head feint, saber-like (this is theatrical swordplay, after all), to the inside, then cuts to the outside. Flynn makes a half-quarte parry, followed by a tierce which parries the attack, and ripostes low in seconde. Flynn parries another attack in tierce, again ripostes seconde, then attempts a head cut which is parried by Levasseur who ripostes inside, which is parried by Flynn in prime. Flynn makes a quick attack in seconde which is parried, and — very nicely and correctly — recovers quickly with a circular parry in the high line to protect himself just in case.

Flynn traverses to the left again, then attempts a flashy, and very “telegraphed,” head attack that would evolve in later films to a “triple moulinet,” which would become his signature move in his film swordplay. And every time I see it, I shout “Time him! Time him! Time him!” in my head to his adversary. Flashy, yes. And just asking to receive a time thrust to the throat!

And so it goes, all very swashbuckling and theatrical.

For the sake of time, for now at least, I’m skipping over most of the following swordplay. As the duel progresses toward the rocks upon which Levasseur will meet his end, there are a couple of long shots which clearly show Rathbone and Flynn doubled by Cavens and Faulkner. Certainly, the publicity still below proves that Cavens doubled Rathbone in one of these shots, and in the same shot on film it is easy to recognize Cavens briefly. Faulkner is almost certainly doubling Flynn in the same shot. The studio was concerned about these obvious doubles — yet in fairness, the film used a great deal of old sea battle shots in the finale, and this is quite obvious.

I do want to mention my three favorite phrases (a phrase is a complete exchange, from start to finish, in fencing, for example: attack, parry, riposte, counter-riposte, counter-attack, &c, until there is a hit or the fencers break distance). All three take place in the final moments of the duel.

First is a croisé in sixte by Levasseur, which is beautifully parried by Blood with a prime, followed immediately by the classic, and very flashy, bind-thrust riposte in tierce (or sixte) to the head, the blade arcing from low to high, almost as a moulinet, although the hit doesn’t quite land. In the right circumstances the technique can disarm the adversary. But nicely done, still!

This is soon followed by Levasseur binding Blood’s blade from sixte to septime, with Blood countering with a yielding parry in tierce as he falls. Again, nicely done!

A quick side note: previous to this Levasseur falls, and Blood gallantly permits him to get up. But when Blood falls, Levasseur does his best to take advantage of the situation, showing the difference in their charaters.

And now the two men are face-to-face at “handy grips!” Here we have the obligatory close-up, hilt-to-hilt, deadly fury in each man’s eyes!

The adversaries quickly get to their feet, surprisingly without punching or pommeling each other, for the final engagement in which, moments after another quick, beautiful croisé in sixte parried in prime, Blood kills Levasseur by lunging off the line — an esquive or, arguably in the language of the day, a volt — and “pinking” him, to use a 17th century term, from side to side. I strongly suspect the finish was inspired by the one in the duel in Rafael Sabatini’s The Black Swan, published three years before.

The film duel from start to finish is just under three minutes, yet time stands still for that short time, so exciting is the swordplay and acting. A timeless scene of piratical yet noble swashbuckling indeed!

Next in the series: The Duel on the Beach in Reality!

Select Bibliography

Ellis Amburn. Olivia de Havilland and the Golden Age of Hollywood. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018.

By

Anon. “Frederic Cavens, 79, Taught Stars Fencing.” New York Times, May 2, 1962.

Anon. “Sealing Wax, Cabbages and Kings.” New York Times, September 30, 1934.

Rudy Behlmer. “Swordplay on the Screen: The Best of it Has Been Due to Belgian Fencing Masters.” Films in Review, June-July 1965.

Laura Benham, “Nothing Short of a Miracle.” Picture Play Magazine, March, 1937.

Thomas Brady. “Meet Hollywood’s Fencing Master.” New York Times, October 5, 1941.

Brendan G. Carroll. The Last Prodigy: a Biography of Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Hong Kong: Amadeus Press, 1997.

Richard Cohen. By the Sword. New York: Random House, 2002.

John Davis. “Captain Blood.” The Velvet Light Trap, No. 1, June 1971.

Edith Durbin. “Rolph and Doug Watch Hungary Win at Sabers.” Los Angeles Times, August 12, 1932.

Jean-Baptiste Dutertre. Histoire generale des Antilles habitées par les François. Paris: Thomas Jolly, 1667.

Alexandre Exquemelin. [John Esquemeling]. The Buccaneers of America. London: Crooke, 1684.

——. [Alexander Olivier Exquemelin]. Histoire des Avanturiers Flibustiers qui se sont Signalez dans les Indes. 2 vols. Paris: Jacques Le Febvre, 1699.

Robert Florczak. Errol Flynn: the Illustrated Life Chronology. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, 2022.

Errol Flynn. My Wicked, Wicked Ways. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1959.

Burt A. Folkart. “Ralph B. Faulkner, 95, Film Swordsman, Dies.” Los Angeles Times, January 31, 1987.

Russ Jones. “Rathbone.” Flashback magazine, June 1972.

Read Kendall. “Out and About in Hollywood.” Los Angeles Times, September 13, 1935.

Benerson Little. The Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish Main, 1674 – 1688. Washington DC: Potomac Books, 2007.

——. The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths. New York: Skyhorse, 2016.

Robert Matzen: Errol & Olivia: Ego & Obsession in Golden Era Hollywood. Pittsburg: Golden Knight Books, 2010.

Maureen O’Hara. ‘Tis Her. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Don Page. “Another Fairbanks Roams Sherwood Forest.” Los Angeles Times, January 19, 1968.

Basil Rathbone. In and Out of Character. New York: Doubleday, 1962.

Casey Robinson. Captain Blood Shooting Script. Warner Bros., 1935.

Rafael Sabatini. Captain Blood: His Odyssey. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1922.

——. The Black Swan. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1932.

Warner Bros. Captain Blood Press and Publicity Package, 1935.

Alma Whitaker. “Stars Who’ve Learned Fencing for Films Make It Latest Indoor Sport.” Los Angeles Times, February 2, 1936.

John R. Woolfenden. “Flock of Handsome Brutes Spring Up as Leading Men.” Los Angeles Times, May 17, 1936.

Copyright Benerson Little 2022. First posted 29 March 2022. Last updated October 23, 2023.

The Duel on the Beach, Part III: In Film!

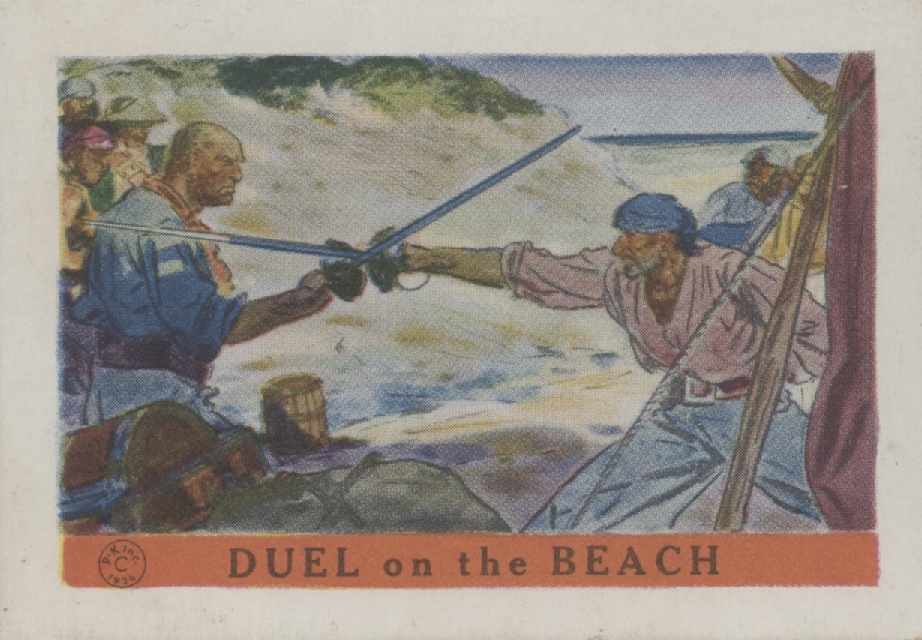

Each media–the written word, the illustration, the motion picture–has a unique ability to convey action. A novel can not only describe but explain swordplay in action; an illustration can bring a moment in time to life and make an entire action timeless; a motion picture can show action as it unfolds and as we might see it were it real.

Of all three, by turning the written description or static illustration into moving action, film may have left us with our most indelible memories and tropes of the duel on the beach. Or so I argue tenuously, for several written descriptions and illustrations come to mind that likewise bring forth indelible memories.

With fiction we must imagine the duel, even when when well-described (but almost always imperfectly nonetheless) and accompanied by the paintings of Howard Pyle or N. C. Wyeth. Written descriptions may suggest extraordinary action, yet even if it’s described accurately and in detail it’s likely that only those who’ve studied swordplay can picture it well in their mind’s eye. Written explanations almost always slow the action down, providing a false tempo and, in the worst cases, a distraction.

Accompanying illustrations can only suggest action. But don’t get me wrong! Often a written description or a painting is far more evocative than a poorly choreographed film duel.

But in film we get to see the duelists move before our eyes. They lunge, parry, and riposte. They plot and execute, they snarl and rejoice. They are living swords actively arrayed in combat before us. And they are often even more dangerously and joyfully inspiring than their descriptions in fiction or accompanying paintings!

This is part three of a five-part series on the duel on the beach in fiction and film. Part one discusses the duel on the beach in fiction, part two the duel in The Black Swan by Rafael Sabatini, and part four the duel in the 1935 film version of Captain Blood. It’s worth reading the first two before this post, but this isn’t absolutely necessary. In this post we’ll take a look at an overview of the duel on the beach in film, with some commentary as well on film duel choreography and especially on one vital aspect of it and all swordplay: tempo.

Actors as Fencers

The actual filming of a duel can take days, and the preparation is typically extensive, beginning with a detailed written play followed by, usually, exhaustive rehearsal. I’ll provide more details on this process in the Golden Age of Film in part four, and look at actors as fencers and at tempo here instead.

Only rarely are actors actually also skilled fencers. From the Golden Age of Film just two come to mind: Cornell Wilde, a Hungarian-born US national saber champion and Olympic qualifier who just prior to the Olympic Games gave up competitive fencing for the theater and soon film, and Basil Rathbone, a studious British amateur who enjoyed swordplay and studied for five years under famous film fencing master Ralph Cavens, after having studied under famous fencing masters Félix Gravé and Léon Bertrand in the UK.

Others have managed to look the part well, with actual skill ranging from none to a little, including Danny Kaye in The Court Jester and Gene Kelly in The Three Musketeers. It surely helped that both were dancers, although for real swordplay, as opposed to choreographed, re-enacted, or fake, it helps even more to be able to sense tempo or rhythm and then break it, by which means one may steal distance and time on one’s adversary, setting him or her up to be hit at the precise moment he or she is least prepared.