Home » Maritime (Page 4)

Category Archives: Maritime

Commands at Sea: The Boatswain’s Call, Pipe, or Whistle, with a Note or Two on Boatswain Speech as Well

Title page to William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, from volume one of The Works of Shakespear edited by Alexander Pope. London: Jacob Tonson in the Strand, 1725.

Ah, the Bard! As someone once pointed out in writing, and I wish I could recall who it was (unless I’m imagining or mis-recalling this), the opening to the Tempest is one of the most evocative in its brevity in all of literature. It brings ship and storm to life immediately. In related fashion, I’m pretty sure it was George MacDonald Fraser who wrote words to the effect that “Enter Mariners wet” is one of the great stage directions of all time. Or perhaps I’m confusing his observation with the former, or even inventing the former from the latter.

But, in this brief yet related digression from swordplay and swashbuckling at sea and ashore, we’re more concerned with another line in the play: “[T]end to the master’s whistle…,” that is, listen to and obey (the “Aye, aye!” spoken or unspoken) the musical commands, shrill, some said, from the ship master’s silver whistle.

Notably, it’s not the boatswain’s whistle Shakespeare mentions, but the master’s, for in the sixteenth century and into the seventeenth the boatswain was not the only officer authorized a whistle. As Nathaniel Boteler wrote in 1634 in A Dialogicall Discourse Concerninge Marine Affaires Betwene the Highe Admirall and a Captaine att Sea, first published in 1685 and known today as the eponymous Boteler’s Dialogues:

“ADMIRAL. How many be the officers that carry whistles in a ship of war?”

“CAPTAIN. They are three: The Master, the Boatswain, and Coxswain, for though the Captain my do the same at his pleasure, yet it is neither usual, nor necessary.”

By the late 17th century, it appears that the silver whistle or “call” was used primarily by the boatswain.

Dutch boatswain’s (or other officer’s) whistle, early 17th century, Rijksmuseum.

Before going further, and with no offense intended to anyone, I want to make sure that readers understand that boatswain is pronounced “bos’n” or “bosun.” I’ve heard “cocks-wayne” rather than the correct “cox’n” (cockswain, one who commands and helms–steers–a ship’s boat) before–including from persons well-educated but clearly un-nautical, not to mention clearly forgetting the first rule of the pronunciation of a new word: look it up!

The boatswain’s whistle, both as a badge of office for any ship’s officer as well as a functional instrument with a large variety of “calls” for ordering hands about, has been around since at least the 13th century according the USN Bluejacket’s Manual (1941 edition), in more or less similar traditional form. It also notes that, although the whistle is commonly referred to as the boatswain’s pipe in the US Navy, the term “call” in reference to it dates to “about” 1671. A writer commenting in 1679 upon the lack of religious fervor among English seamen during the English-Dutch war at sea 1672 to 1673, complains that “a Lieutenant’s Command for a Rope for the Boat, shall be sooner answered with Boatswain’s Call, than the Bell for Prayers…”

However the Reverend Henry Teonge, chaplain aboard the HMS Assistance 1676 to 1678, still referred to it as the boatswain’s whistle: “He had a neat coffin, which was covered with one of the King’s jacks, and his bo’sun’s silver whistle and chain laid on the top (to show his office) between two pistols crossed with a hanger drawn.”

The English boatswain had other badges of office as well, including a short cane or “bamboo,” its tip whipped with marline, for encouraging laggard seamen by cracking it on their backs and pates, although sometimes a simple rope’s end served as well. And there was the cat-of-nine-tails too, a dark badge of office best kept out of sight except when in use. But it was the boatswain’s whistle that was his definitive badge of office, and I’m sure that boatswains of the past were just as proud of their silver call as boatswain’s today are: “It is not so much by his fine Silver-call, as the illustrious Chain that it hangs by, that is the distinguishing Badge of his Post, and which he’s as proud of as my Lord Mayor is of his, and prouder,” wrote Ned Ward in 1707.

The whistle was an important means of directing seamen about their duties. Again, Ned Ward: “The Boatswain is a Kind of a Jack with a Box, for let him but whistle once, and you have a hundred or more Cartesian Puppets, pop up upon Deck, and run about, and streight disappear again in an Instant.”

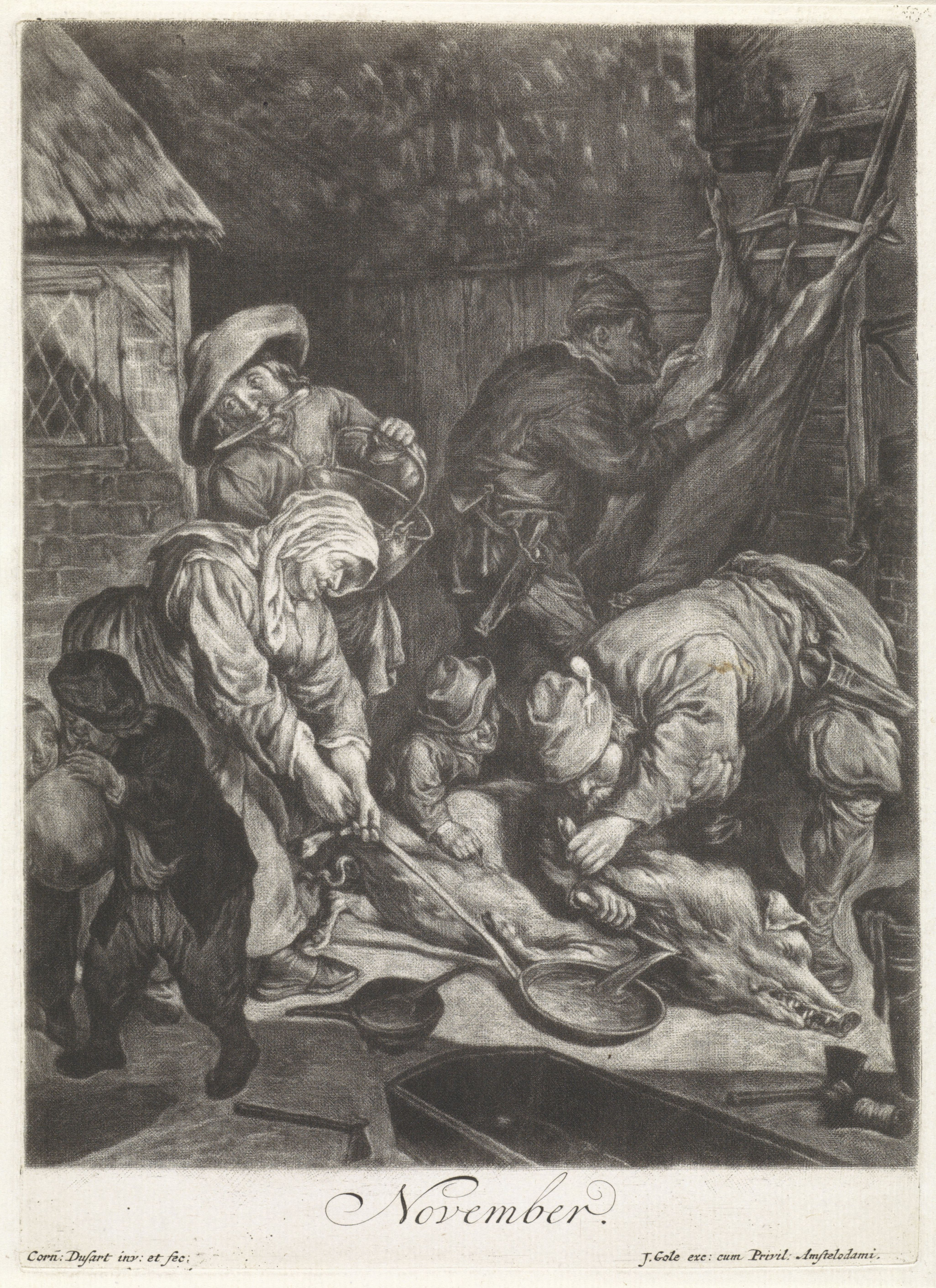

In the 17th and 18th centuries an English boatswain’s duties included the custody, keeping, repair, and management of all rigging, anchors and cables, and sails; the hoisting in and out of cargo, stores, and boats; the management of all of the ship’s colors; the calling up, via his whistle, of gangs, watches, &c. for, as Boteler put it, “exertions of the their works and spells (as they call them), and to see that they do them thoroughly; and to keep them in peace in in order with one another.” This last duty was that of what on land was handled by the Provost Marshal. At sea, it was the boatswain who punished seamen for their shortcomings. This included everything from flogging wrongdoers to placing them in the bilboes to ducking them at the main yardarm. In the Dutch navy, the boatswain’s duties include keelhauling as well (see “Keelhauling, in Living Color”).

In battle the boatswain and his mates, along with some of the other crew if the occasion warranted, were tasked not only with repairs to the rigging, but often with managing the sails. Shortened sail was typically used in battle in order to reduce the number of crewmen required to manage it, leaving the majority to handle the guns great and small, and the small arms as well.

At sea aboard USS George Washington (CVN 73) Sep. 9, 2002: Boatswain’s Mate 3rd Class Bethany McDonald. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate Airman Jessica Davis.)

In the modern US Navy, the boatswain–thankfully, after a brief period of insanity in which ratings were abolished, they’re now restored–has similar duties, in particular in regard to the various rigging aboard modern ships, the hoisting of boats and stores, and so on. The boatswain’s pipe remains ever present, and modern US Navy boatswain’s calls, performed by the US Navy band, can be found here.

The most common call I remember was “Piping the Side,” that is, the piping of a captain, admiral, or on occasion, some dignitary over the side during a formal ceremony shipboard or ashore. I remember various other calls shipboard as well, on both surface ships and submarines, but for the life of me I can’t remember them in detail except that “All Hands” was common, or perhaps it was “Pass the Word,” and, like everything else, the calls came over the 1MC (the general PA aboard a US Navy ship or shore command) except in the case of the piping the side ceremony, for we were always present for them.

But boatswains then and now had other means to motivate seamen: language, particularly when spiced with “cursing and swearing.” Sailors in general have long been known for their use of foul language, and boatswains in particular had, and have, a reputation for creativity, eloquence, wide vocabulary, and, as often as not, lyricism in their swearing. Ned Ward noted that:

“He must certainly believe there can be no such Thing as Hell-fire under Salt-water, else he would never be giving himself so oft as he does to the Devil; but how frequently soever he damns himself, he is sure to damn others much oftener. In short, he’s a Fellow that will throw away ten times more Oaths and Strokes in hoisting out a Barge, than in boarding an Enemy.”

The boatswain’s excuse for his language is a simple one: “But, Zounds, he’ll cry, what would have me do? A man without Noise, is a Thing without a Soul, and fit for nothing but a Pissing-Post.”

As for my own experience, I never knew a real US Navy boatswain, at least not a Chief Boatswain’s Mate, who couldn’t out-swear anyone except another boatswain. A boatswain’s work–dealing with fouled lines, for example–naturally inspires foul language, which in turns lubricates the work at hand and helps get it done. At times I’d swear it has motivated not only crew but rigging or equipment itself.

My favorite example of a boatswain’s cursing, however, or perhaps my second favorite (I’ll save a particular modern description for a later post), may be that of Ned Ward’s Royal Navy boatswain, whose elegant oxymoron is straight to the point:

“Get up, all Hands to Prayers, and be damned.”

Indeed.

REFERENCES (Not Cited in Detail Above)

Anon. Observations on the Last Dutch Wars, in the Years 1672 and 1673. London: 1679.

Nathaniel Boteler. Boteler’s Dialogues. Edited by W. G. Perrin. London: Navy Records Society, 1929.

Benerson Little. Chapter 14, “Tarpaulin Cant and Spanish Lingua,” in The Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish Main, 1674-1688. Washington DC: Potomac Books, 2007.

Henry Teonge. The Diary of Henry Teonge. Edited by G. E. Manwaring. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1927. (Teonge’s original manuscript was first published in 1825.)

United States Navy. Bluejacket’s Manual. 1941.

Ned [Edward] Ward [By the Author of the London Spy]. The Wooden World Dissected in the Character of a Ship of War, 7th ed. London: Booksellers of London and Westminster, 1760. Originally published in 1707.

Copyright Benerson Little 2017. Last updated May 3, 2017.

Keelhauling, in Living Color

The Keelhauling of the Ship’s Surgeon of Admiral Jan van Nes. Lieve Pietersz Verschuier. 1660 – 1686. Note the enormous crowd gathered for the punishment. (Rijksmuseum.)

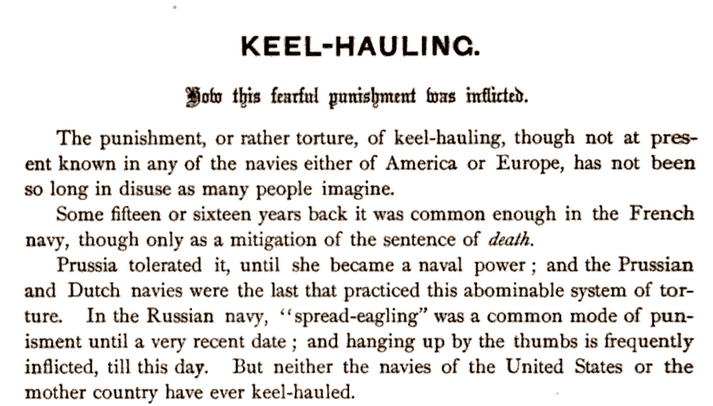

As is the case with much pirate history, a great deal of it is wrong, often either anachronistic or culturally mis-associated, or not specifically associated with piracy per se, but with the maritime in general. And so it is with keelhauling, a Dutch practice at first, to which the French and a few other nations later added their small marks.

But keelhauling had little to do with piracy, but this hasn’t stopped it from being including in discussions about pirates and piracy, nor included in pirate fiction and film, most notably and recently in the fourth season of Black Sails. (Full disclosure: I was the historical consultant to Black Sails for all four seasons.)

The original Dutch practice, as described in “A Relation of Two Several Voyages Made into the East-Indies” by Christopher Frick and Christopher Schewitzer, 1700:

“He that strikes an Officer, or Master of the Ship, is without hopes of pardon to be thrown into the Sea fasten’d by a Rope, with which he is thrown in on one side of the Ship, and drawn up again on the other, and so three times together he is drawn round the Keel of the Ship, in the doing of which, if they should chance not to allow Rope enough to let him sink below the Keel, the Malefactor might have his brains knockt out. This Punishment is called Keel-halen, which may be call’d in English “Keel-drawing.” But the Provost hath this Priviledge more than the other, that if any one strikes him on Shoar, he forfeits his hand, if on Board, then he is certainly Keel-draw’d.”

There are several notations of keelhauling and other punishments in the journal of Dutch Admiral Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp in 1639. Typically the keelhauled seaman was drawn three times beneath the ship, apparently not too tightly for he was usually whipped on his “wet bum” with a rope’s end afterwards. For lesser offenses, ducking from the yardarm was employed. In some cases, a seaman convicted of serious offenses might be ducked, keelhauled, whipped, lose his wages, and be discharged. In the case of infirmity due to age or illness, the physical punishments might be stayed, and the seaman discharged instead.

Detail of the victim, from the painting above. The keelhauling line has been rove through a block at the end of the mainyard, and would be similarly rigged on the opposite side. (Rijksmuseum.)

From An Universal Etymological English Dictionary, edited by Nathan Bailey, 1765.

A mid-1850s century French version, described by a former midshipman in the British navy and published in Onward magazine, November 1869, was conducted slightly differently:

The writer continues with a description of what he witnessed:

Terrible indeed!

N. B. Spanish Keelhauling

I’ve also seen one reference to the Spanish using keelhauling: Gemelli-Careri, describing his voyage aboard the Manila galleon in 1697, notes that he heard tell of a passenger, during the senas ceremony, being made to “facendogli passere sopra il Vascello,” from which event he died. The period English translation gives this as keelhauling, although sopra means over, not under. So, while it might be keelhauling, it might also be ducking, which is more likely given the ceremony of senas, or signs of land. Ducking might be inconvenient, even frightening to some, but wasn’t usually fatal. Keelhauling often was.

N. B. Keelhauling’s Ancient Origin?

A number of web articles and books, both popular and scholarly, note that keelhauling is of ancient origin. However, this is probably not the case. Scholar Henry A. Ormerod in Piracy in the Ancient World (1924) claims that an image on an ancient Greek vase shows keelhauling, and he has reproduced the image as the frontispiece to his book. However, I see nothing in the image to suggest keelhauling per se. Instead, it appears to depict some form of water torture of prisoners who had their hands tied and were thrown overboard, perhaps pulling them back to the surface as they begin to drown. However, the image does not appear to show keelhauling as we define it—the dragging of a victim beneath the vessel from one side to another. In fact, the victims have only one line attached: keelhauling generally requires two.

Similarly, some scholars and other writers note that the Lex Rhodia of 800 BCE describes keelhauling as a punishment for piracy, but there are actually only a few short paragraphs of the Lex Rhodia that still survive and they don’t discuss punishment for piracy, so I’m not sure where this idea originated. It may be a misreading of Ormerod, who suggests that it may have described punishments for piracy. The only line that refers to piracy is in regard to responsibility for paying the ransom of a ship to pirates. This is a common problem in history: the repetition of misinformation or incomplete information as fact.

My thanks to writer Sylvia Tyburski, whose questions to me on the subject caused me to review the facts on the purportedly ancient origin of keelhauling! I’ll post a link to her article as soon as it’s available.

Copyright Benerson Little 2017. Last updated July 10, 2018.

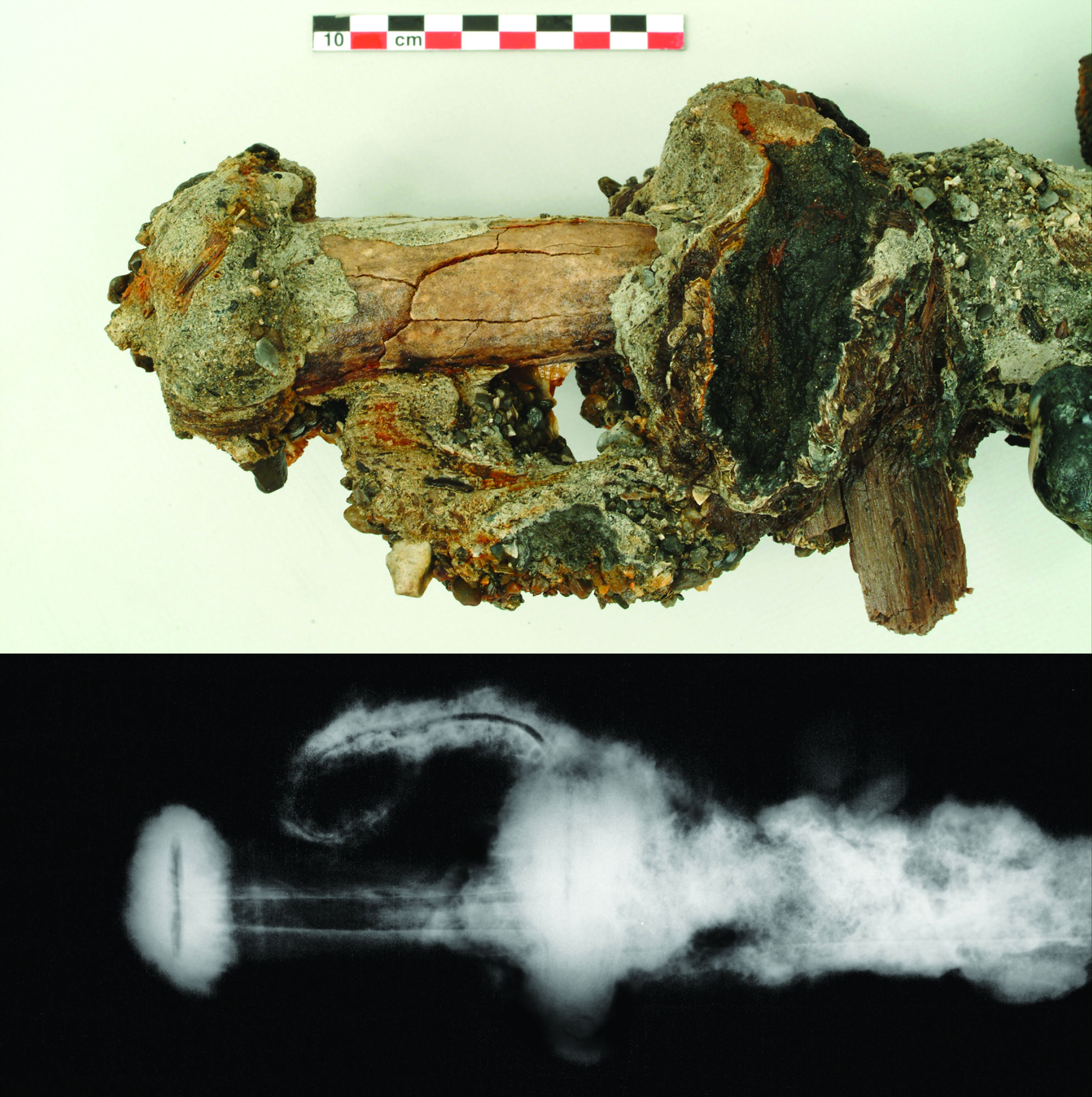

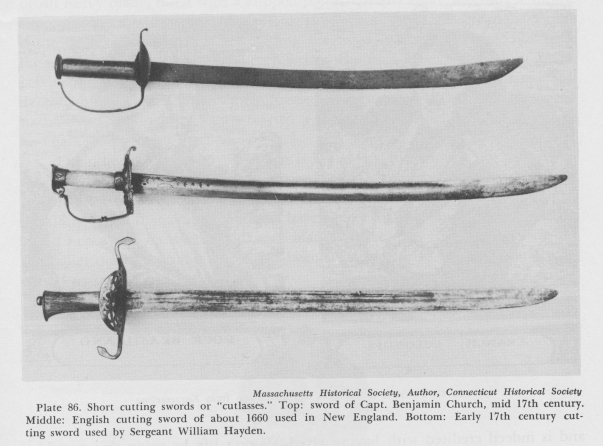

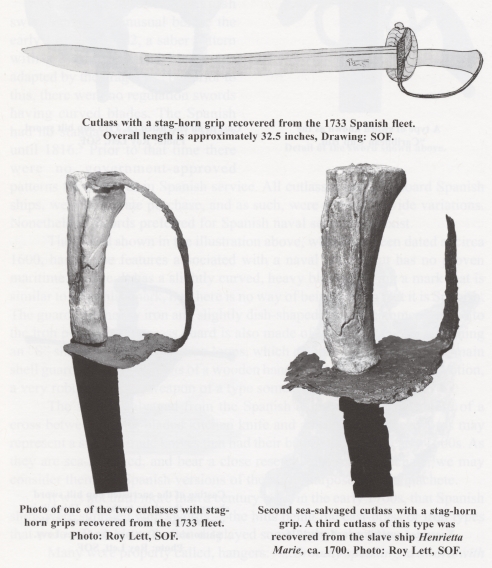

Buccaneer Cutlasses: What We Know

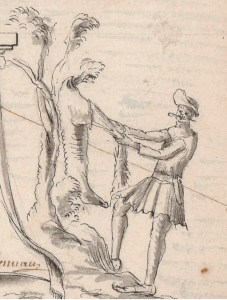

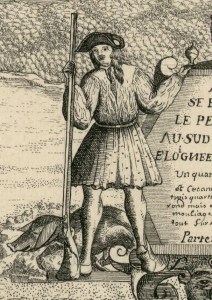

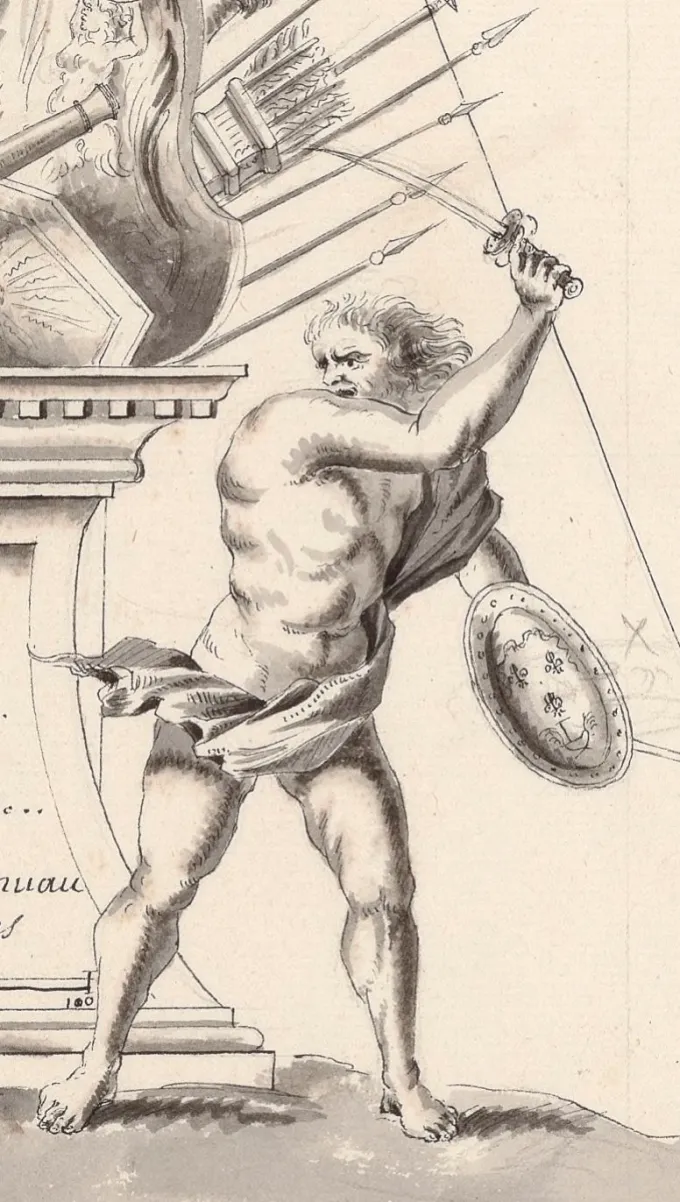

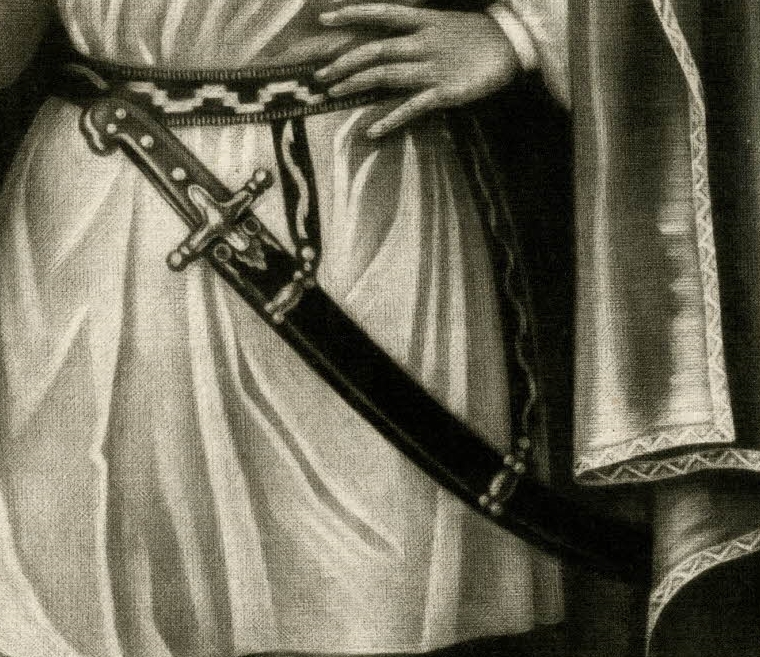

Eyewitness image of a flibustier with captured Spaniards in chains. From the French chart Carte particulière de la rivière de la Plata by Paul Cornuau, probably 1684 based on a nearly identical chart he drew of the River Plate dated 1684. (French National Library.)

EXQUEMELIN’S HEROES & THEIR CUTLASSES

Although the fusil boucanier–the long-barreled “buccaneer gun” of which more blog posts are forthcoming–was the primary weapon of the buccaneer and flibustier, the cutlass was an invariable part of their armament, which also included one or two pistols and a cartouche box (sometimes two) that often held as many as thirty cartridges each. Grenades, firepots, and boarding axes were additional specialty weapons. English/black bills were fairly common aboard English men-of-war of the era (and halberds aboard the French) as well. Some seamen (and we assume some buccaneers) carried broadswords or backswords instead of cutlasses, and English seamen were known as adepts with cudgels and handspikes (see Samuel Pepys re: the latter). In a separate post I’ll discuss broadswords, backswords, cudgels, and handspikes.

Yet in spite of all the romance of buccaneers and their swords–cutlasses usually in reality, but often rapiers in cinema–we don’t know as much about the swords themselves as we would like. Much of what we think we know is based on conjecture, and this conjecture is based on what little we know about cutlasses and hangers of the late 17th century. Unfortunately, the archaeological evidence is for all practical purposes non-existent in regard to demonstrable buccaneer swords 1655 to 1688.

Cinema, the source of much of the popular image of the pirate cutlass, almost always gets these swords wrong. Typically they are anachronistic, often imitations of nineteenth century “soup bowl” hilts (and occasionally authentic 19th century cutlasses) drawn from prop stocks. Money is always a concern in film-making, and it is much cheaper to use existing swords than to make historically accurate ones in large quantities, or, too often, even in small quantities. Good historical consulting and the willingness to follow it is, of course, mandatory, but some filmmakers take the view of “Who cares? Hardly anyone will notice, what matters is that the swords look cool or ‘Rock and Roll’ or otherwise meet audience expectations, and anyway, we don’t have the budget for accurate ones, the actors and computer graphics have consumed it all.” On occasion, though, we do see fairly accurate swords in cinema–just not very often.

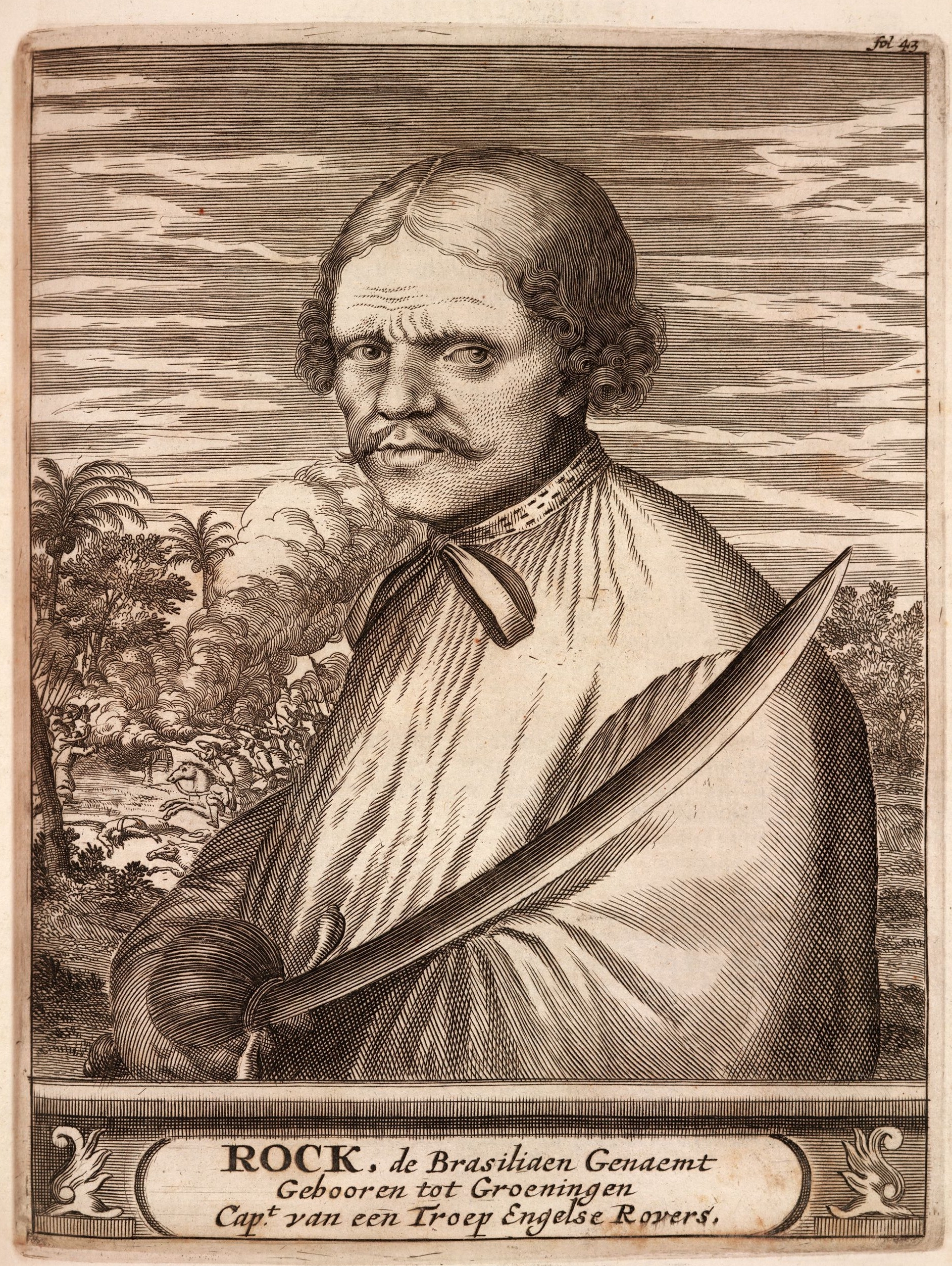

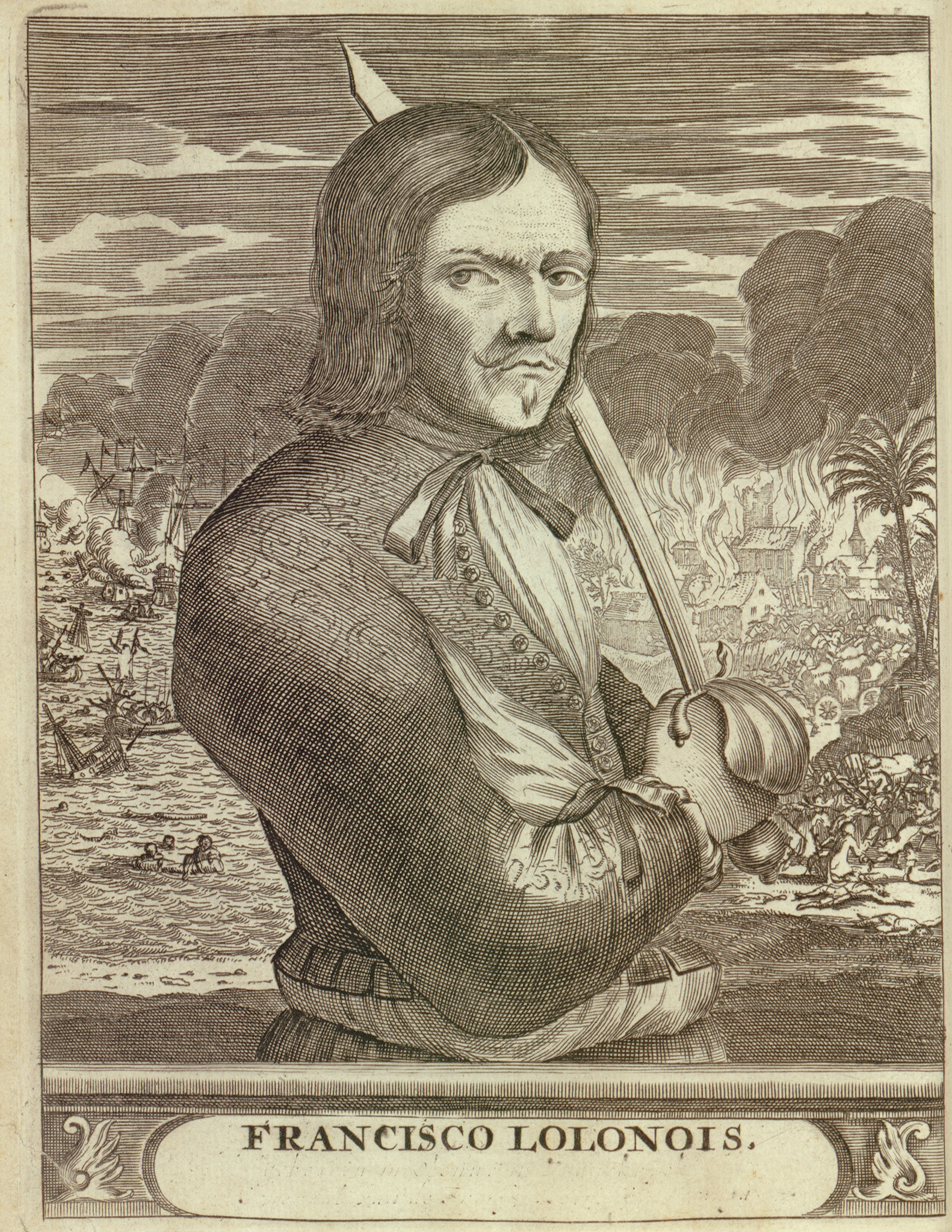

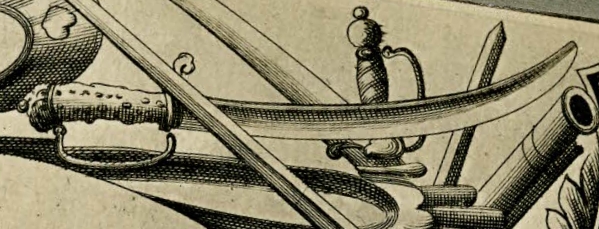

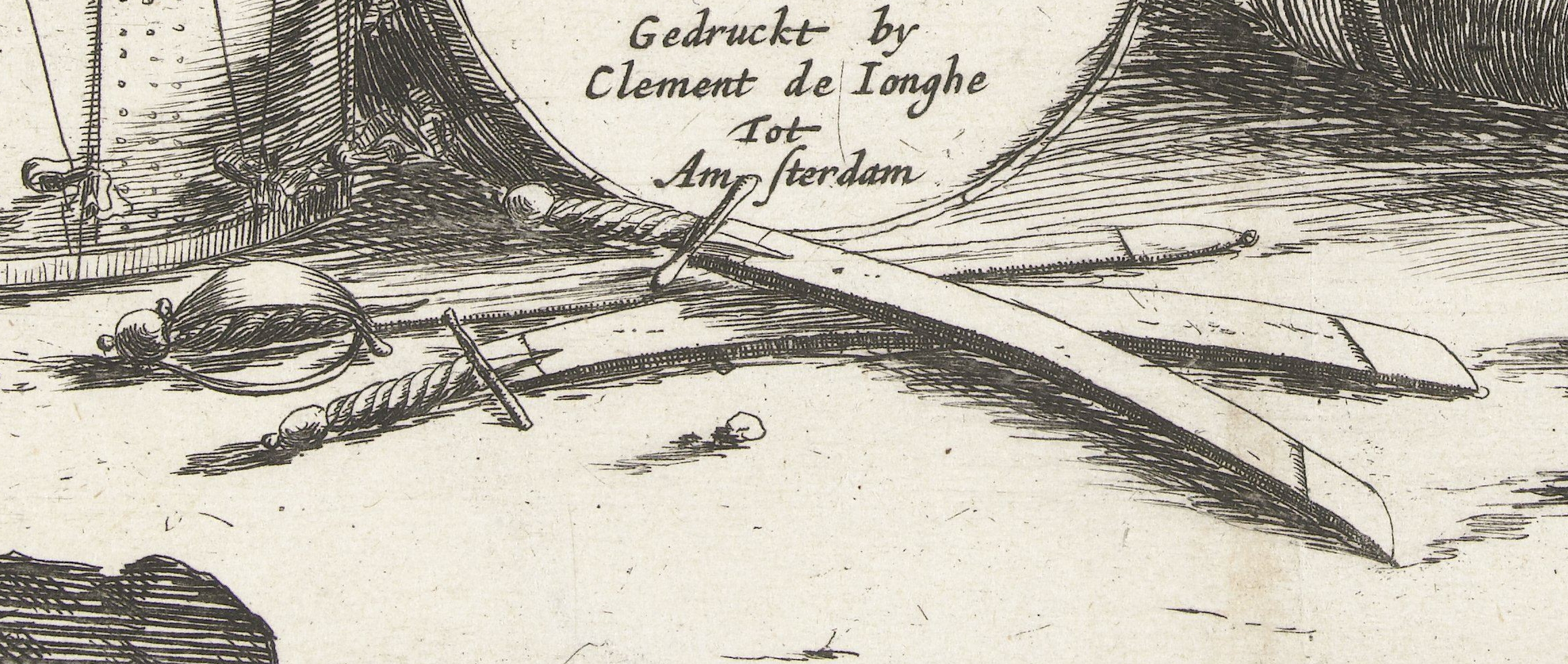

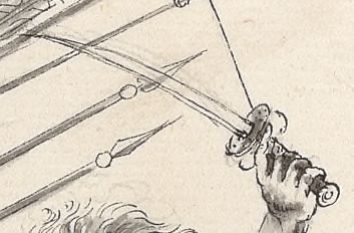

Our typical idea of a “true” pirate cutlass is taken from the illustrations, such as that above, in Alexandre Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America. First published in Amsterdam in 1678 in Dutch, the illustrations have been copied to other editions, typically with little or no alteration. Herman Padtbrugge, draftsman and engraver, may have been the illustrator according to the British Museum. It is unknown how much influence Exquemelin had on him, or on whomever was the illustrator. In other words, it is unknown how accurate the physical representations the buccaneers are, nor how accurate their arms and accoutrements. The cutlasses depicted in Exquemelin may simply reflect the illustrator’s Dutch nationality and familiarity with Dutch arms. Notably, the large seashell-like shells of the hilt do have an obvious maritime flavor, and are the perfect arme blanche with which to equip a buccaneer in an illustration.

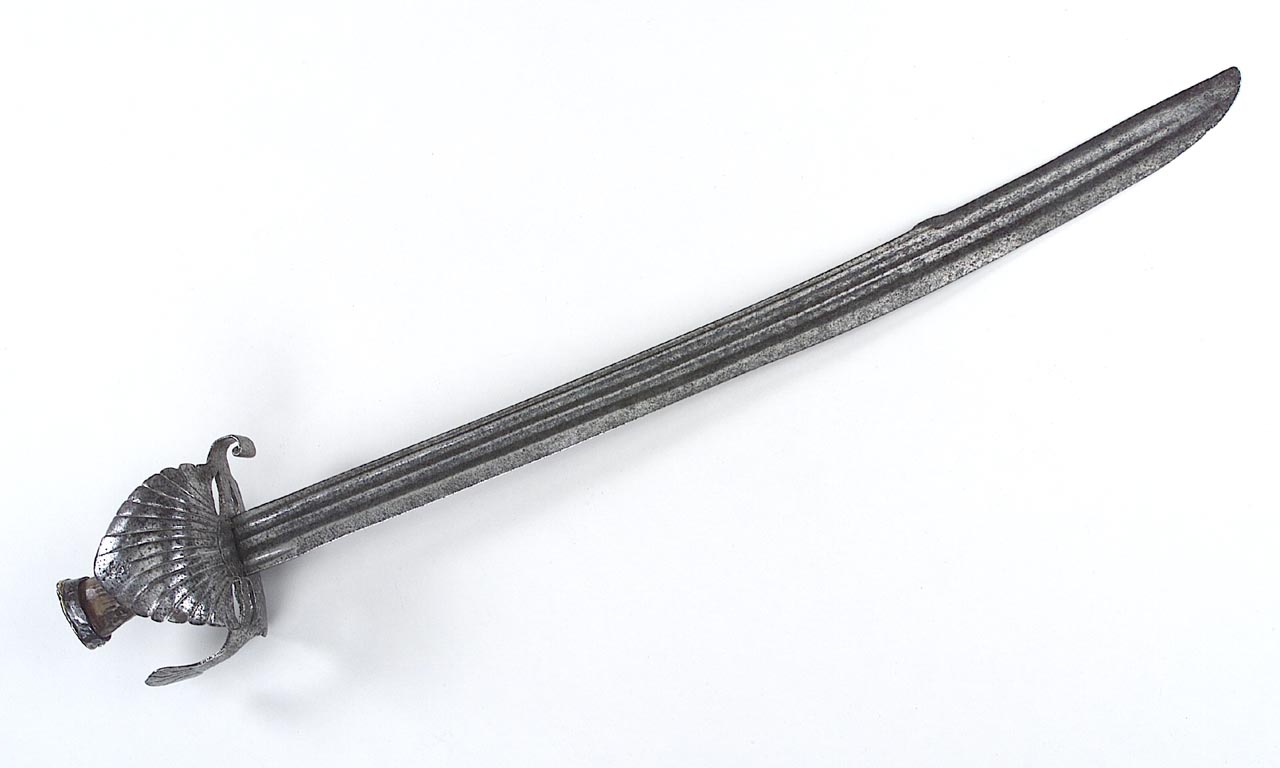

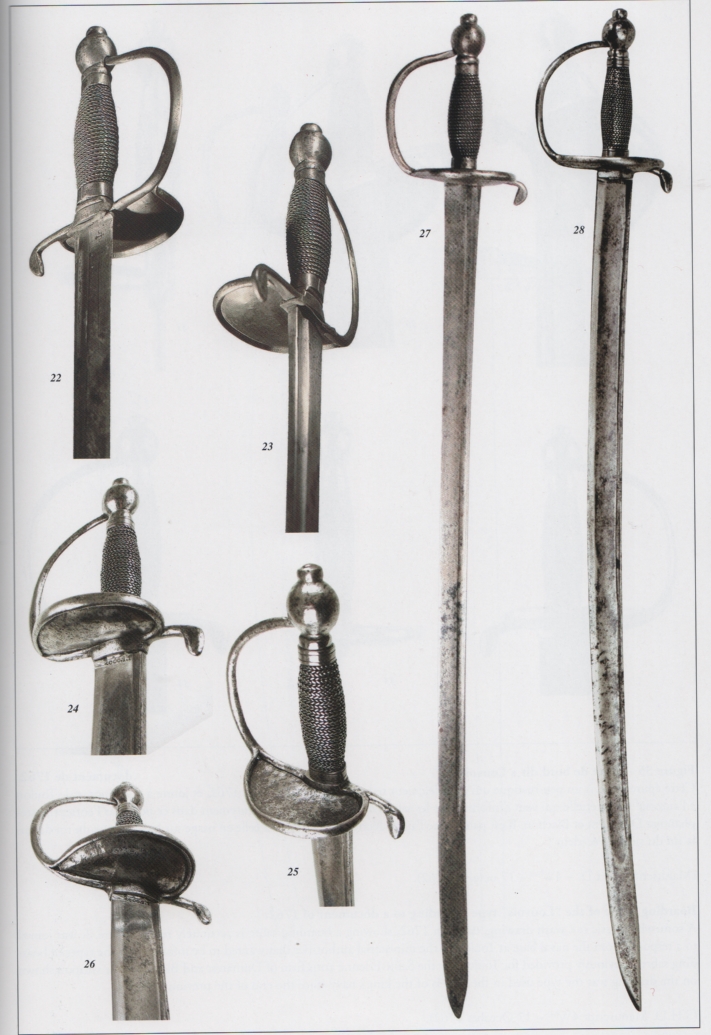

Even so, the cutlasses are accurate representations of classical late seventeenth century Dutch or German weapons with large iron shell-hilts, manufactured well into the mid-18th century with basically no design changes. Basically, these cutlasses are German-style dusacks with simplified hilts. Similar shell hilts were manufactured by other European nations, albeit typically with somewhat smaller shells. The English, for example, produced some cutlasses or hangers with somewhat smaller but similar shells during the 1660s. The Dutch and German shells are usually quite large and often scalloped, the pommels often heavy for balance, the blades mildly to strongly curved, often with clip points. (Notably, cutlasses or hangers seen in paintings of Dutch naval captains and admirals have only small shells.)

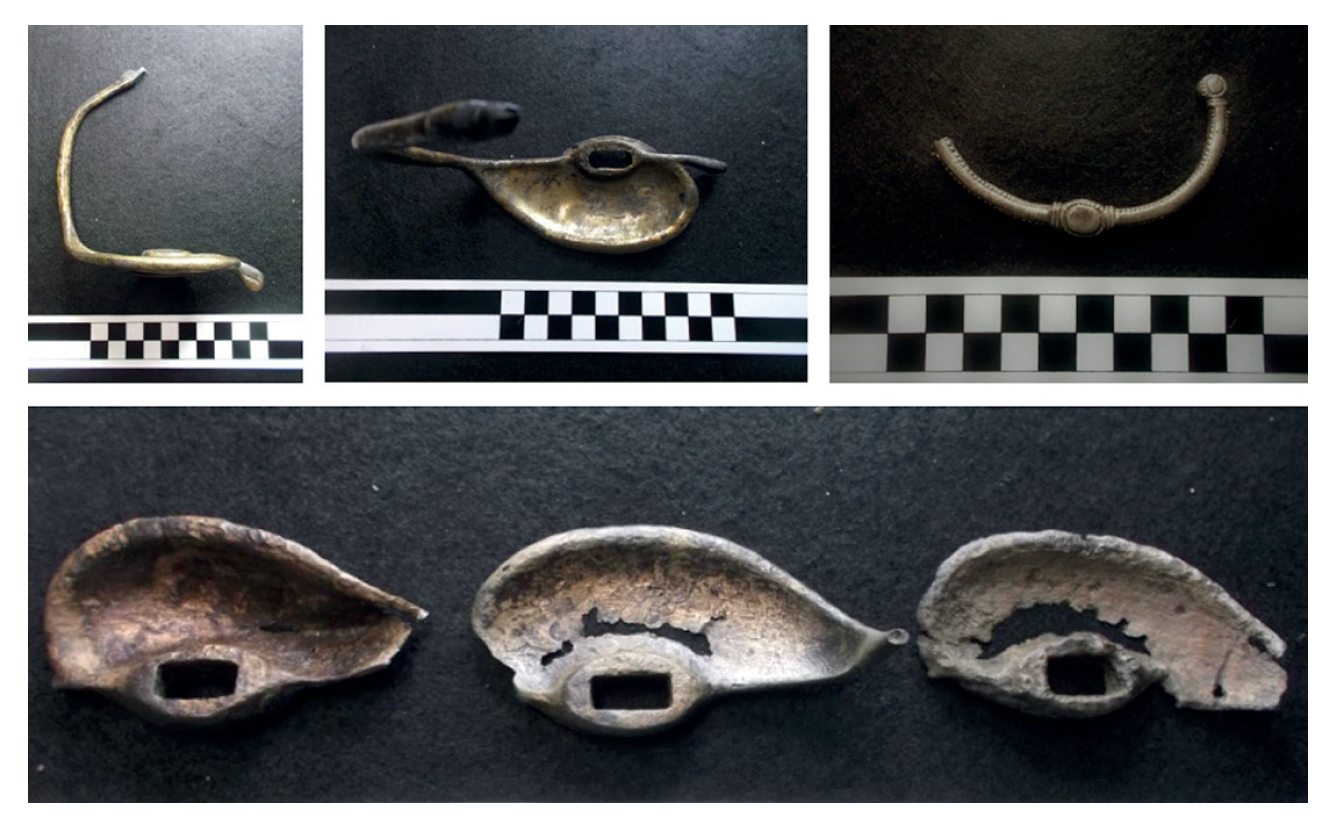

Typically these large shell-hilts may have had a single shell on the outside, with or without a thumb ring on the inside, although usually with one; or a large outside shell and smaller inside shell, both most commonly facing toward the pommel; or a large outer shell with a small inner shell that narrows into a thumb ring. A thumb ring may be present or absent in the case of two shells; occasionally it may be separate from the inner shell. These heavy-hilted cutlasses may have two short quillons with no knuckle bow, or a conventional short or medium upper quillon along with a lower quillon converted to a knuckle bow as in the image below. Pommel style and grip style and material–wood, bone, antler, brass, shagreen (“fish skin,” ray skin) over wood, wire over wood, leather over wood, or even iron–vary widely. Blade balance varies just as widely, with some heavy-bladed cutlasses balanced more like cleavers than fencing swords. This is not a criticism: cleaving strokes with a cutlass are quite effective at close range.

The cutlass wielded by Rock the Brazilian above appears, on close examination, to have a single outside scalloped shell, two quillons (although it’s possible the lower quillon might actually be a knuckle bow, but I doubt it is), a heavy pommel, and a thumb ring.

L’Ollonois above holds a typical Dutch or German scalloped shell-hilt cutlass of the late 17th century. Its shell is medium to large, the quillons small and curved, the pommel round and heavy, the blade moderately curved and with a clip point useful for thrusting. It appears it may have a thumb ring or an inner shell, probably the former, or both.

EYEWITNESS IMAGES OF BUCCANEER & FLIBUSTIER CUTLASSES

What we do not know is how common these swords were among buccaneers and flibustiers. Doubtless there at some among them, given how common these cutlasses were. However, the most direct evidence we have of the sort of cutlasses used by these adventurers comes from several drawings of flibustiers in the 1680s by Paul Cornuau, a cartographer sent to survey French Caribbean ports, in particular those of Saint-Domingue (French Hispaniola, modern Haiti). Typically he included local figures flanking his cartouches, and most of these figures are flibustiers and boucaniers. Notably, these are eyewitness illustrations! (See also the The Authentic Image of the Real Buccaneers of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini (Updated) and The Authentic Image of the Boucanier pages for other eyewitness images.)

In the image at the very top of the page, the flibustier holds a cutlass with a small hilt of indeterminate shape, without a knuckle bow, and with a strongly curved clip point blade. There is no baldric: he wears a sword belt of the sort common at the time, with a pair of hangers with loops (one of them is not shown) hanging from the belt itself. None of these period images of flibustiers show baldrics, although they were a common way of carrying a smallsword into the 1680s for civilian use, and prior to this by infantry and other military branches. However, most infantry began abandoning them in this decade, if not earlier, and they remained in use afterward primarily by mounted troops and Scottish Highlanders.

In the image above, we can tell little of the cutlass belonging to the flibustier on the left except that it has a clip point and that it may be of brass, based on its probably monster, beast, dog, or bird pommel, although some iron pommels have a similar profile, and some iron hilts have similar brass pommels. It appears to lack a knuckle bow. Its scabbard is worn from the belt. The flibustier on the right holds a cutlass with a moderately curved blade and clip point. Its hilt has two shells, both small and scalloped. Its pommel may also be of some sort of beast or bird, although we cannot be certain, and there is no knuckle bow. Again, the scabbard is worn from the belt. A similar illustration of a flibustier (on the Authentic Image post, of a flibustier at Île-à-Vache, 1686, from a chart by P. Cornuau) shows only a scabbard with an obvious clip point. It, too, is worn from the belt.

In the image above we have more detail of the hilt. It is clearly of the monster, beast, dog, or bird pommel type, almost always brass. There is a bit of shell showing, but what sort we can’t tell other than that it is scalloped, although if brass we know it is comparatively small. Again, there is no knuckle bow. Notably, the scabbard, which also has a chape (metal protection for the tip of the scabbard), does not necessarily reveal the blade form: it may be with or without a clip point.

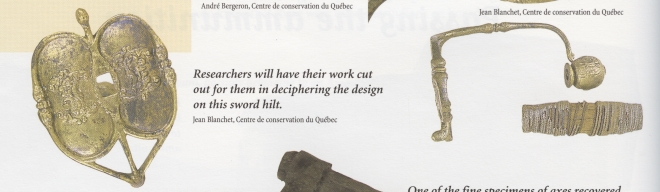

So, what would these cutlasses depicted by Cornuau actually have looked like? And what is their origin? For the latter answer, the cutlasses could be of Dutch, English, or possibly French origin. There are numerous English cutlasses and hangers of this form still extant, and of the Dutch as well; the Dutch are often credited as the likely creators of this form. There is less information, though, and few examples, of French cutlasses from this period, although the French may have produced similar arms. There are numerous examples from English and Dutch naval portraits. Most of these swords appear be gilded brass hilts. Although some flibustiers and buccaneers may have carried cutlasses with gilded hilts, most were probably simple brass or iron.

PERIOD EXAMPLES

Starting with brass-hilt cutlasses similar to most of those in the Cornuau illustrations, we see a variety of shells and pommels above, although most grips appear to brass, or possibly wire, twisted in a sharply ascending manner. Pommels include a bird of prey, lions, and one or two indeterminate forms similar to that shown in the illustration above of the flibustier armed and equipped to march against a town or city.

If we consider that this form of cutlass is likely Dutch in origin, it behooves us to look closely at one. The image above is of the hilt of the cutlass of famous Dutch admiral Michel de Ruyter. Note that it too lacks a knuckle bow.

Below are several hilts with a variety of knuckle bows. The 4th from the left looks somewhat like a transitional rapier or smallsword hilt, but it appears it may lack the usual arms of the hilt, plus the sword hangs low from the belt and at a steep angle, making it possible that it is a hanger or cutlass. The last image has a knuckle bow of chain, as if a hunting hanger, which it might well be. Again, we see dog or monster pommels, and also lion pommels.

The hilt shown above may be that of a hanger or cutlass, or other cutting or cut-and-thrust sword such as a broadsword or backsword. The shells, while identical to those of a period smallsword, are, with the form of the knuckle bow, very similar to those found on some late 17th century brass-hilted English naval cutlasses. However, it is impossible to know what sort of blade was mounted in the hilt. The Elizabeth and Mary was ferrying New England militia, who were armed with a variety of non-standard arms.

Note the similarity of the sword of Sir Christopher Myngs–possibly a transitional sword with a “rapier” style blade, or a light cut-and-thrust broadsword–to that of the shipwreck hilt.

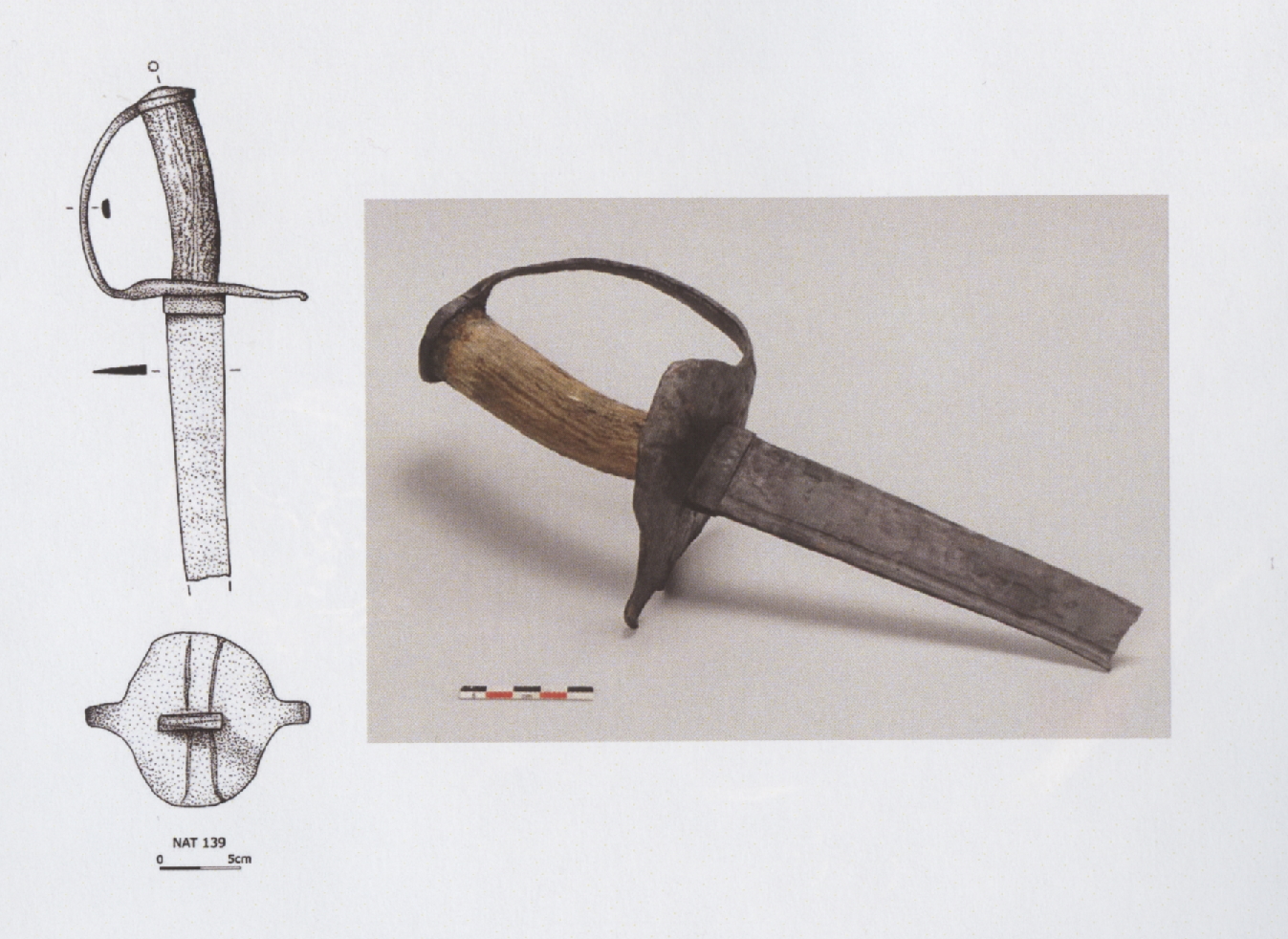

Thankfully, there remain a fair number of extant examples of hangers and cutlasses other than the few shipwreck artifacts, although maritime or naval provenance is often difficult to prove. A few examples are shown below. Note that two of them have iron shells and/or knuckle guards, with brass pommels. Some buccaneer cutlasses could have been of this form.

In addition to online sources, several good illustrations of brass-hilt cutlasses, which were typically more ornate than iron-hilted, can be found in William Gilkerson’s Boarders Away, With Steel (Lincoln, RI: Andrew Mowbray, 1991). Images of cutlasses from Harvey JS Withers’s collection for sale and sold can not only be found online, but in his book, The Sword in Britain, volume one. There are other available sources as well, including several additional reference in this blog.

Below is a detail from an illustration of the famous Jean Bart–a Flemish corsaire in French service–showing him with a cutlass. (Several other period images show him armed with a smallsword, but at least in the image below he is on the deck of a ship.) The cutlass has what appears to be a bird pommel, a small outside un-scalloped shell (or possibly a disk shell), an upper quillon, and a clip point. The hilt is probably brass, and, given its owner, might be gilded.

The illustration of Bart’s cutlass may represent a common cutlass carried by French naval and privateer officers, or it may represent Bart’s Flemish nationality. It appears to be a fairly accurate representation of a Dutch or English cutlass or hanger as discussed previously, although, if we look at the pistol in the belt, we may draw some reservations about its accuracy. The pistol, carried as many were, tucked behind the sash or belt on the right side to protect the lock and make for an easy left-handed (non-sword hand) draw, has errors: both the belt-hook and lock are shown on the left side of the weapon, for example, and the lock is inaccurately drawn. The lock should be on the right side, and the cock and battery are unrealistic. It is possible, but highly unlikely, that the pistol represents a double-barreled pistol with double locks.

OTHER CUTLASS HILT FORMS & SOURCES

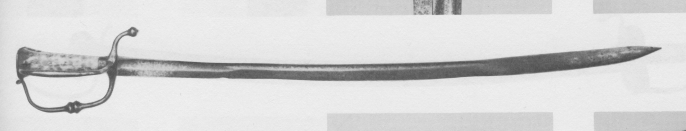

Other forms were doubtless used, including the Dutch/German discussed above, as well as the very common smaller iron shell-hilt cutlasses as in the example below. Both William Gilkerson in Boarders Away, With Steel (Lincoln, RI: Andrew Mowbray, 1991) and Michel Petard in Le Sabre d’Abordage (Nantes: Editions du Canonnier, 2006) include a fair number of illustrations of common iron-hilted 17th and early 18th century cutlasses. These cutlasses range from a simple outside shell with no thumb ring, to inside and outside shells (the inside typically smaller) with or without thumb rings. On occasion the inside shell faces forward, especially if small. Invariably either an upper and lower quillon exist, or an upper quillon and knuckle bow. Grip material varies as with the Dutch cutlass first described, although wood and bone are the most common materials.

Another common enough form with a pair of bows, one for the knuckles, the other for the back of the hand, is shown below. This form is occasionally seen combined with small shells on brass hilts as well, as in an example above.

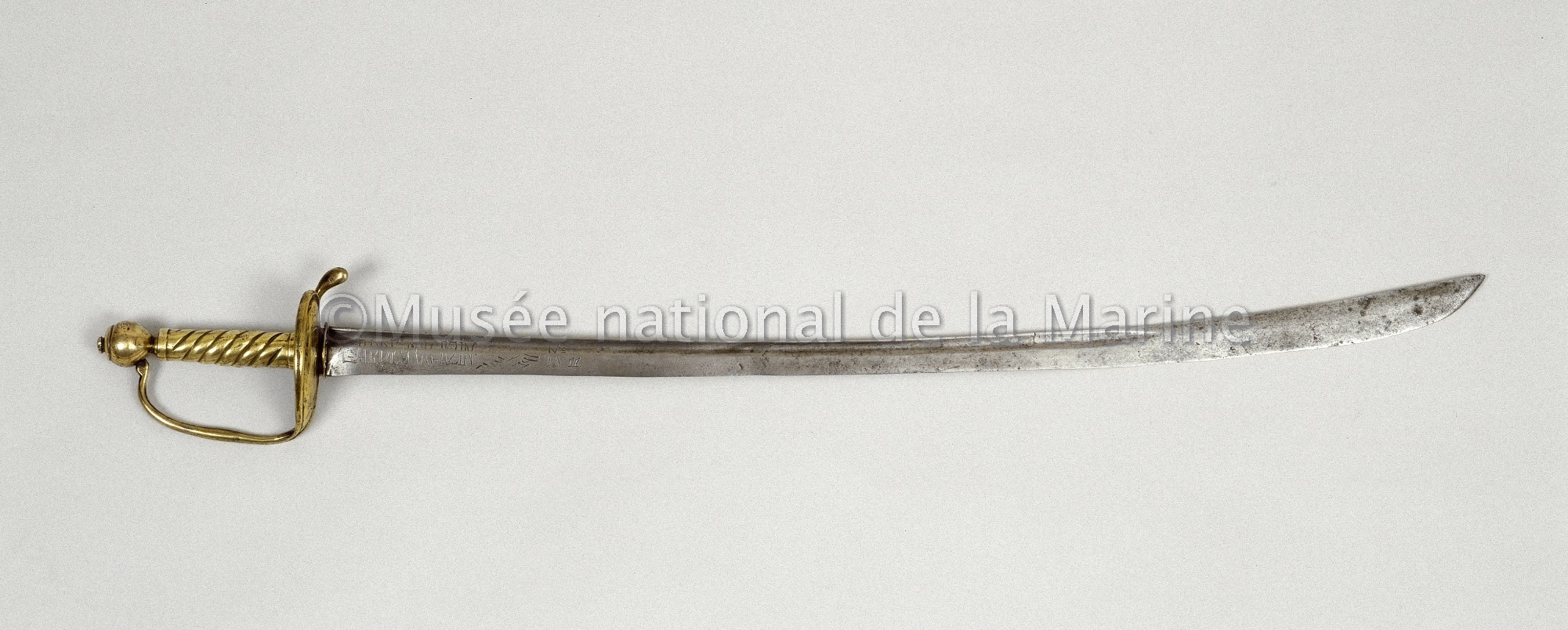

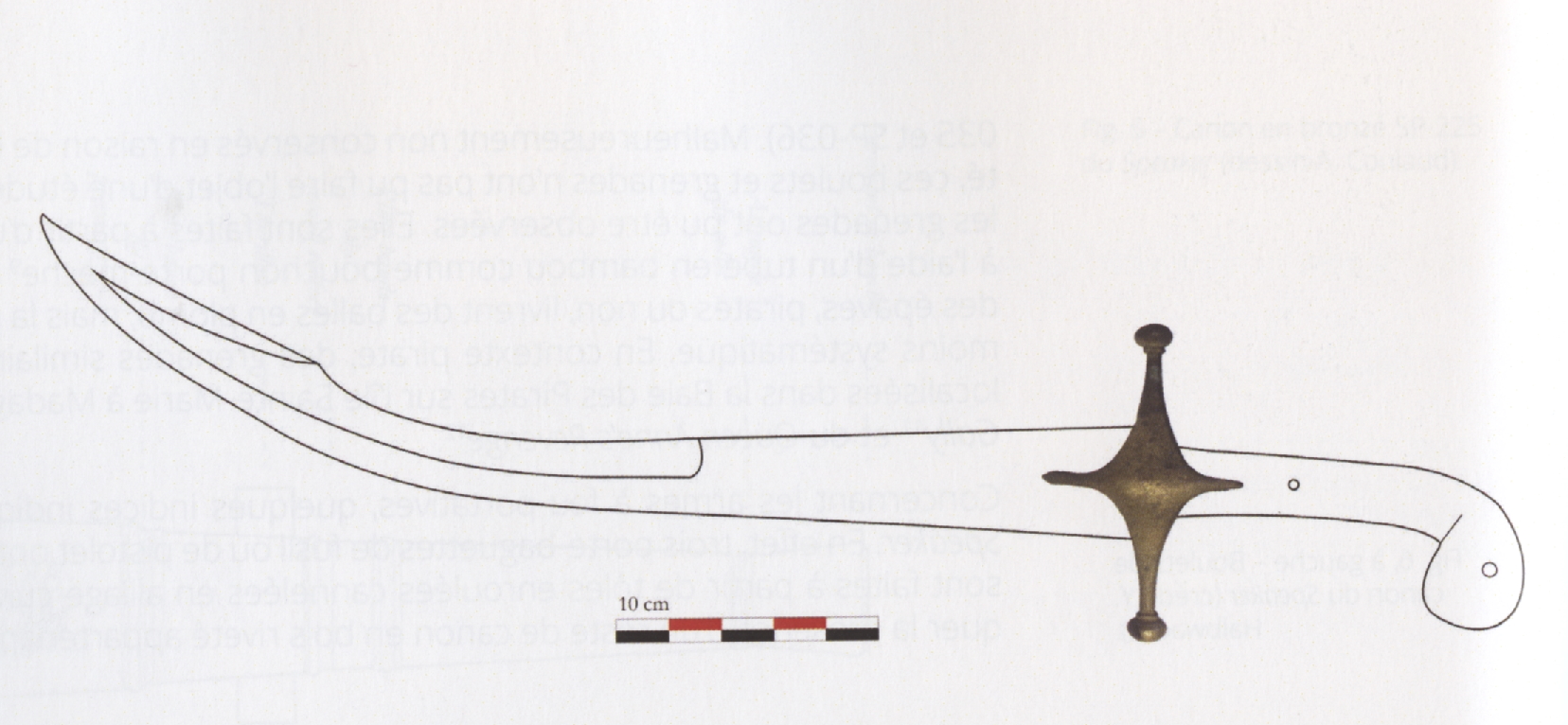

Of the late seventeenth century cutlass identified as French, Michel Petard in his excellent Le Sabre d’Abordage describes only one form, shown below. It is iron-hilted and has a single simple outside shell, a small quillon, a knuckle bow carried to an un-ornamented pommel. Almost certainly there were brass-hilted versions of this sword; the French grenadier sword of roughly the same date is identical, except in brass. It’s quite possible, even likely, that some flibustiers carried swords like these, both iron- and brass-hilt versions, but they do not appear to match those in Cornuau’s illustrations.

French paintings of admirals and other officers are typically of no help in identifying French cutlasses or hangers. Most of these portraits are highly stylized and show officers in full armor. When swords are shown at all they are typically smallswords (epees de rencontre).

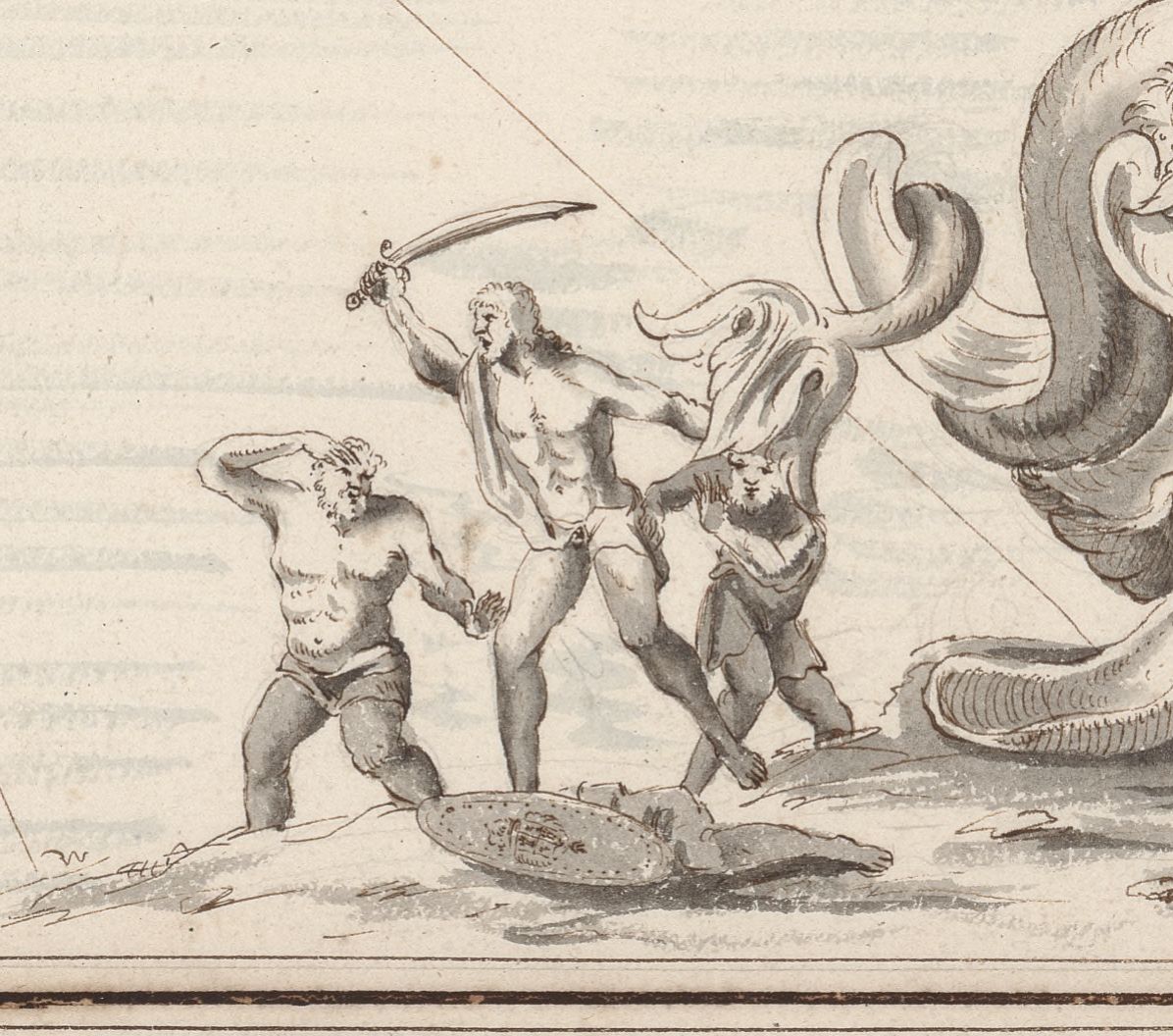

In Cornuau’s allegorical image above, perhaps of France as Neptune or Mars, the swordsman wields a cutlass of indeterminate shell construction (possibly a simple flat disk, as in the case of some 17th and 18th century hangers and cutlasses, see image below, or a crudely drawn double shell hilt), a cap pommel, and mildly curved blade with a sharp, non-clip point and a single fuller along the back of the blade. Again, it is unknown whether this cutlass is intended to portray a flibustier weapon. Similar examples from the 17th and 18th centuries are known, including a Spanish cutlass. In general, these cutlasses consist of a simple roundish shell with a small upper quillon and a knuckle bow, or of a simple roundish shell with a small upper and lower quillon forged from the same piece of iron.

The sword above is identified by the Mariner’s Museum as a 17th century Spanish naval hanger (cutlass, that is). The shell, quillon, and knuckle guard are iron, as are the plates on either side of the handle. The hilt is without doubt that of an espada ancha (wide or common sword) of New Spain from the 17th or 18th century, commonly used by rancheros and mounted troops as both a weapon and tool similar to a machete. Although most had straight blades, the curved blade of this one does not necessarily mark is as maritime, although surely some of these swords were found aboard Spanish vessels in the Caribbean, particularly those sailing from Mexican ports such as Veracruz. A lack of blade markings is common. Chamberlain and Brinkerhoff in Spanish Military Weapons in Colonial America, 1700-1821 note that swords like this are commonly seen from the late 18th to early 19th centuries. In other words, the date may be incorrect.

Another reportedly (by an auction house) 17th century Spanish cutlass above. Iron-hilted, 22″ blade. The design is similar to the previous: knuckle guard, small upper quillion, small shell or outer guard. It too appears to be an espada ancha; I’d like to know how the auction house dated it. Its date too may be incorrect.

From the first quarter of the 18th century, the Spanish cutlass hilts above were authorized in 1717. The French influence is obvious.

The allegorical image above by Cornuau, shows a man–again perhaps France depicted as Neptune or Mars–wielding a falchion or falchion-like cutlass with a simple hilt, round pommel, and curved blade with clip point. At the man’s feet lies a corpse cloven in half through the torso. It is unknown whether this cutlass is intended to portray a flibustier weapon. That said, there were similar mid- to late 17th century cutlasses and hangers, the one below for example.

Another form that may have been seen among buccaneers is that of the Eastern European short scimitar or saber, or even long as depicted below.

CUTLASS DESIGN AND USE

A few notes on the design and use of the cutlass are in order. Note that a thumb ring serves a very useful purpose in a sword with an unbalanced hilt, that is, one in which the outside shell is significantly larger than the inner, or in which the inside shell is entirely absent: it permits a stronger grip, preventing the blade from turning as a cut is made. If one’s grip is not firm when cutting with an unbalanced hilt, the blade may turn slightly and cut poorly or not at all. In cutlasses with a single large outside shell, any looseness in the grip will cause the cutlass to turn in the hand toward the heavier side. The thumb ring also provides some protection to the thumb against cuts.

Ideally, for a cutting blade to cut properly, a “draw” or drawing action must be made if the blade is straight or mostly straight. Some backsword and broadsword texts make obvious note of this, that the blade must be drawn toward its wielder in order to cut. (It may also be pushed away, in the 18th century this was known as a “sawing” cut.) However, the diagonal cuts from high outside to low inside, and high inside to low outside, have a natural “drawing” motion as the arm is brought toward the body. To make a powerful drawing cut is fairly easy: simply draw the elbow toward the body as the cut is made. A lightly laid on cut with a straight edge, one made with small arm movement, will require a deliberate drawing motion.

Sweeping cuts are the most common sort of drawing cuts, but they are dangerous in practice unless one is mounted (and moving quickly) on a horse, or has a shield, targe, or other defense in the unarmed hand. Sweeping cuts are easily “slipped”–avoided–and as such leave the attacker vulnerable to a counter stroke in tempo. They are also subject to counter-attacks in opposition. Tighter cuts may also be made with a natural draw, and this sort of cutting action is generally preferable when fighting without a shield or targe, as is the case in boarding actions. Note that wide sweeping cuts are more likely to injure one’s companions in a boarding action, and to get caught up in rigging and fittings.

In particular, a straight-bladed cutlass or other sword requires a drawing action in order to cut well. A curved blade has a natural cutting action, and the more curve there is the less drawing action must be added–the severe curve suffices. However, the greater the curve the less suitable for thrusting a sword is. A direct thrust made with such a sword (see the two heavily-curved examples of Tromp’s swords, for example) will result not in the tip penetrating the adversary, but with the first inch or two of the edge hitting. It is very difficult to push the edge of a sword deeply into tissue, and most wounds caused this way are superficial. Note that the clip point found on many cutlasses is designed to make a curved blade more effective at thrusting.

I am going to devote only a few words to the popular misconception that a heavily-curved sword, such as a scimitar, can be used to thrust effectively. Its true thrusts must be hooked, and the typical example one finds in discussions by self-appointed “experts” is that of a hooked (aka angular) thrust made after one’s adversary has parried quart (four, inside). In theory, the attacker can roll his hand into tierce (pronated), and slip around the parry with a hook thrust. This will only work if the attacker also has a shield or targe in his (or her) unarmed hand, or is wearing a breastplate: otherwise there is nothing to prevent the adversary’s riposte. In other words, try this with a curved cutlass, and while you may be able to make a thrust (which may or may not penetrate ribs) as an arrest or stop hit against a riposte, you will almost certainly also be on the receiving end of a powerful cut. In other words, try this at your peril in the 17th century.

I can think of only one exception to this advice: Andrew Lonergan (The Fencer’s Guide, 1777) notes that the Hussar saber, with its curved blade, has a natural cavé or angulation against quart, tierce, or prime parries (or any other parries, in fact). Notably, he’s referring to action on horseback with horses typically moving at speed–the rider, executing the natural angulation with the saber, can escape the riposte as he rides by, while simultaneously cutting or thrusting with cavé, which at speed will push not the point but the edge through neck or arm. This is much more difficult to do with a simple thrust or thrust with lunge, and, as noted lacks the protection of riding past. “The bent of their swords will afford them an unavoidable Quarte-over-the-arm, or a Cavè [sic: the wrong accent is used on cavé in the original text].” N.B. a thrust, or rather, a thrusting cut can be made with the edge at the tip, but requires great force (i.e. from horseback at a canter or gallop) and is, as Lonnergan notes, primarily effective against the soft tissue and joints of the arms and neck.

One of the most effective cuts with the cutlass is a powerful drawing cut, vertically high to low, the hand drawn down and backwards, from close quarters distance, or even when grappling if the blade is free. It is a highly effective cut: I have cut through twelve inches of brisket with it.

All this said, cleaving–non-drawing–blows can cut through skin and muscle, and even break bones. One need only to test this with a common kitchen cleaver to see the efficacy of such blows, although they are generally inferior to those made with a natural drawing action. Also, a cleaving blow, even with a dull blade, can still break bones. Getting hit on the head with a heavy cutlass would be akin to getting hit with a steel rod.

The grossly exaggerated Thomas Malthus edition of Alexandre Exquemelin’s The History of the Bucaniers (1684) notes the following of the cutlass in buccaneer hands:

“Never did the Spaniards feel better carvers of Mans-flesh; they would take off a Mans Arm at the shoulders, as ye cut off the Wing of a Capon; split a Spanish Mazard [head or skull] as exactly as a Butcher cleaves a Calf’s Head, and dissect the Thorax with more dexterity than a Hangman when he goes to take out the Heart of a Traitor.”

But this may not be much of an exaggeration. Of an English seamen put in irons aboard a Portuguese carrack circa 1669 out of fear he might help lead a mutiny, passenger Father Denis de Carli wrote:

“He was so strong, that they said he had cleft a man with his cutlass, and therefore it was feared he might do some mischief in the ship, being in that condition [drunk for three days on two bottles of brandy].”

Cutlass balance determines how well the cutlass may be wielded in terms of traditional fencing actions, and which forms of cuts work best. A heavily-balanced cutlass, with much of its weight forward around the point of percussion (that is, near the end of the blade), makes for very effective cleaving and close cutting actions, and will cut well with even crude swings. However, it is less effective for skilled fencing. A well-balanced cutlass–less point or tip heavy–is a more effective fencing sword, in that it permits quicker actions such as cut-overs, but requires a bit more training or finesse to cut well. In other words, give a cleaver to an unskilled seaman, but a better-balanced cutlass to one with reasonable skill at swordplay. All this said, a skilled “complete” swordsman or swordswoman can fence pretty damn well with anything.

Switching to a discussion of how the cutlass is held, the cutlass grip, like that of period broadswords and backswords, is a “globular” one–the thumb is not placed on the back of the grip or handle. Placing the thumb on the back of the handle, assuming there is even room (typically there is not), given the weight a cutlass and its impact against its target, may result in a sprained thumb, possibly a broken one, and at the very least the thumb being knocked from the grip, thus losing control of the weapon. The “thumb on the back of the handle” grip is suitable for lighter weapons only.

Shells are quite useful–mandatory, in my opinion–to protect the hand. A single outside shell, especially in conjunction with an upper quillon and a knuckle bow, provides merely adequate protection to the hand. The inside hand and forearm remain vulnerable to an attack or counter-attack (best made in opposition). The addition of an inner shell, typically smaller, goes far to maintain adequate protection to the hand. As already noted, inner shells were usually smaller, given that the inner part of the hand (the fingers, basically) is smaller than the outer, typically 1/3 to 2/5’s of the entire fist. Again, though, differently-sized shells, especially if the difference is significant, will unbalance the weapon, making a thumb ring useful for gripping well and preventing the edge from turning and thereby not cutting.

But perhaps the cutlass’s greatest virtue, and what would have made some of its technique unique as compared to the broadsword and saber (from which late 18th through early 20th century cutlass technique was drawn), was its utility at “handy-grips.” I’ve covered this subject elsewhere, but besides the close cleaving or drawing cut described above, pommeling would have been common, and “commanding” (seizing the adversary’s hilt or blade) and grappling would have been common as well. F. C. Grove in the introduction to Fencing (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1893) wrote: “One of us once saw a sailor of extraordinary strength seize a cutlass close to the hilt, where the edge is blunt, and break it short off.” This was an extraordinary example of a surely commonplace tactic.

There are few descriptions of the cutlass in action, but of those that exist, they are quite illustrative. Of a fight between English slavers and Africans on the Guinea Coast in 1726, William Smith wrote:

“[F]or they press’d so upon us that we were Knee deep in the Water, and one of them full of Revenge, and regardless of his Life, got out into the Water behind me, resolving to cleave my Skull with a Turkish Scimitar, which Ridley perceiving, leap’d out of the Canoe, and just came time enough to give him a BackStroke, which took the Fellow’s Wrist as Was coming down upon my Head, and cut his Hand off almost. Ridley with the violent Force of the Blow at once snap’d his Cutlass and disarm’d the Negroe, whose Scimitar falling into the Water, Ridley laid hold’of, and us’d instead of his Cutlass.”

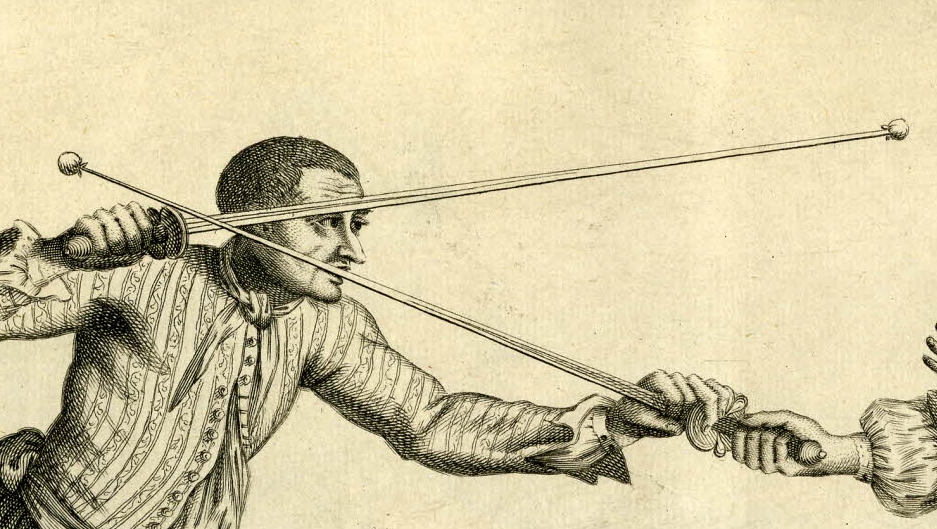

There are unfortunately no cutlass texts dating to the age of the buccaneer, and few fencing texts discuss even related weapons until the 18th century. The only 17th century exception I can think of offhand is Francesco Antonio Marcelli’s treatise on the rapier (Regole Della Scherma, 1686), in which he devotes a few pages to saber versus rapier, noting quite correctly that the saber, and therefore also falchion, cutlass, &c., is a killing weapon even at very close range. See below. In The Golden Age of Piracy I discuss to a fair degree what we know from period accounts about how the cutlass may have been used.

I’ve discussed training in the cutlass elsewhere, including a few notes in my Fencing Books For Swordsmen & Swordswomen post. In Sea Rover’s Practice I note that there was clearly some instruction at sea, although it may have often been ad hoc as was often the case ashore. Late seventeenth century French privateer captain Duguay-Trouin hired a fencing prévôt (assistant to a fencing master) to help school his crew in swordplay (and later found himself in a rencontre, swords drawn, with the man in the street), and mid-eighteenth century English privateer captain “Commodore” Walker had training sessions aboard his ship, the officers practicing with foils, the seamen with singlesticks.

The only pirate captain we know of who was said to have held swordplay practice aboard ship is John Taylor in the Indian Ocean in the early 18th century, according to prisoner Jacob de Bucquoy (Zestien Jaarige Reize Naa de Indiën, Gedaan Door Jacob de Bucquoy, 1757, page 69). Taylor’s pirate crew reportedly held practices, as Commodore Walker would later do, with foils and single-sticks. I am a bit leery of this report, however. Although it certainly may be true, it is tied to a criticism of Dutch East Indiamen captains and crews, with de Bucquoy suggesting that the pirates were more disciplined and trained in a manner that the East Indiaman crews were not. Most historical accounts show a great deal of indiscipline among pirate crews.

However, it is impossible to maintain proficiency in arms without practice, thus it is likely that pirates practiced swordplay. The question is to what degree, and whether the practice was formal or informal. Further, there is the question of whether or not pirate captains deliberately outfitted their vessels with foils and single-sticks or “cudgels” as they were commonly known. Doubtless Duguay-Trouin and Commodore Walker did, but, assuming the Taylor account is correct, Taylor’s were probably from captured stocks. That said, singlesticks are easily crafted (but not so foils). Please note that real weapons were not used for fencing practice! This would soon enough destroy their tips and edges, not to mention that it would be very dangerous even with protection. Fiction and film have, for ease of plot not to mention laziness or ignorance, given many the false idea that swordplay was practiced with real swords. A single-stick or cudgel, by the way, differs from a real sword “only that the Cudgel is nothing but a Stick; and that a little Wicker Basket, which covers the Handle of the Stick, like the Guard of a Spanish Sword, serves the Combatant, instead of defensive Arms.” (Misson’s Memoirs and Observations in His Travels Over England, 1719.)

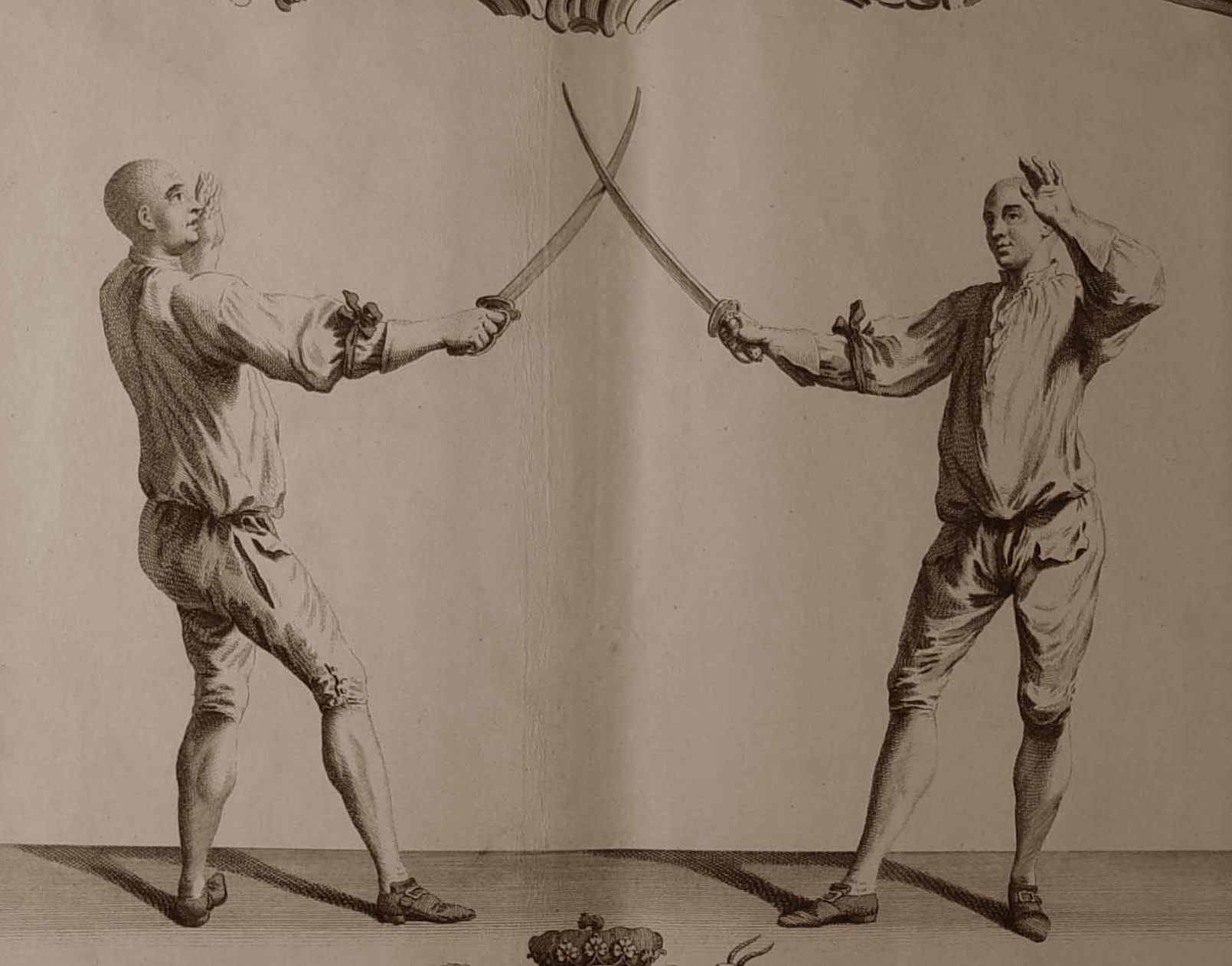

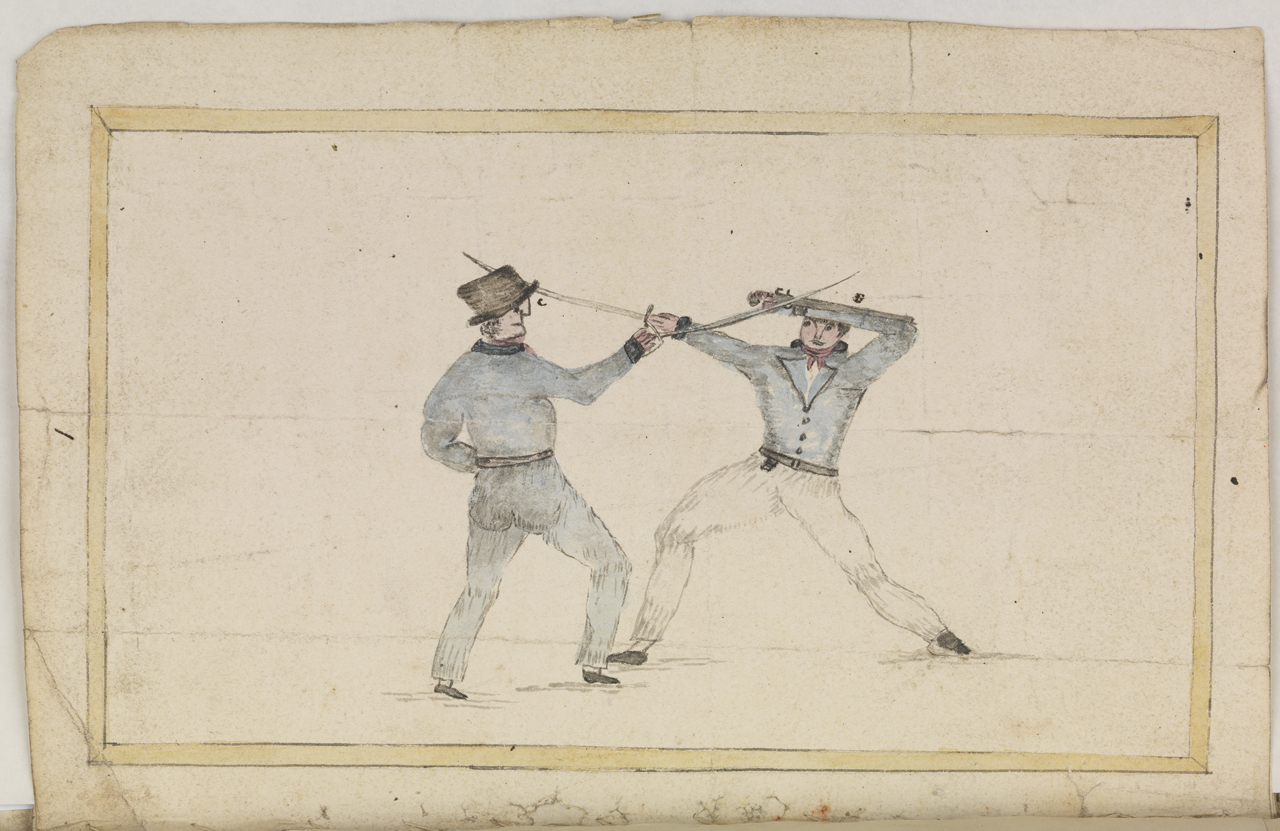

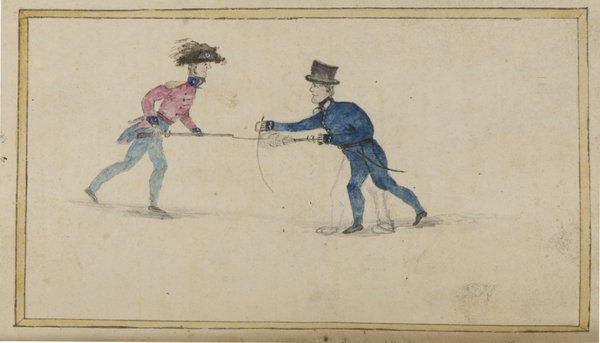

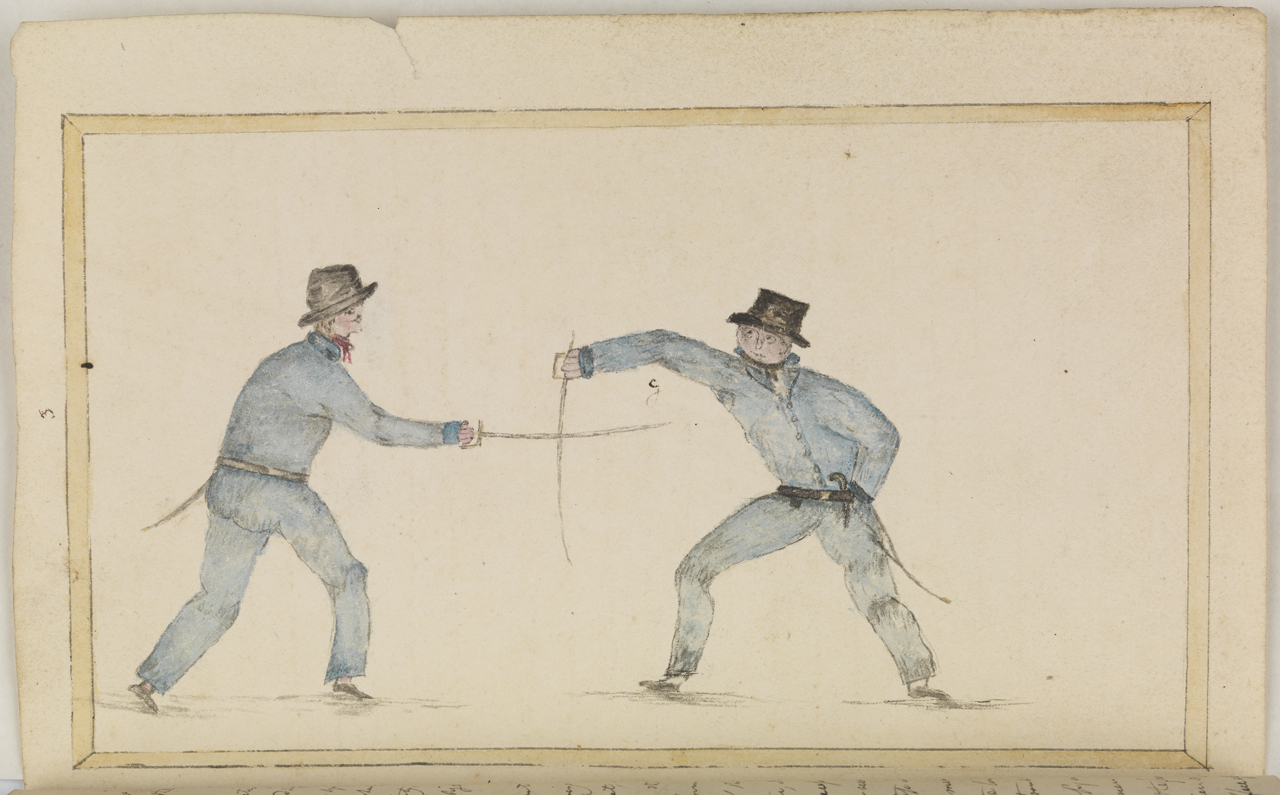

Possibly one of the more practical texts, and even then incomplete, is that of Lieutenant Pringle Green in manuscript in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. He discusses boarding actions and associated combat, with some ideas of his own. Although more than a century later than our period, there is likely a fair similarity between the two eras. See the images below.

Lieutenant Green’s text makes a few important notes. First, the seaman armed with a cutlass must know more than just protect left (inside, quarte), protect right (outside, tierce), protect head (St. George, modern saber quinte), and cut & thrust. High seconde and prime–“falloon” or hanging guards–are useful for parrying, and are mandatory to parry a musket, as he illustrates, as also half-pikes (Girard illustrated this with the smallsword in the mid-eighteenth century). The low seconde and prime parries are just as important. Second, the pistol can be used to parry when reversed along the forearm. In fact, even when holding the pistol by the grip a parry can be made, and also a forehand blow with the barrel. However, it is well to remember that Pringle Green’s text is not an exposition of hand-to-hand naval combat in actual practice, but his ideas on how it might be done better. Caveat emptor.

I’ll also point out here a rather irksome issue on occasion, that some students of historical swordplay still attempt to argue that parries with cutting swords were made with the flat rather than the edge. This is nonsense. There are some forms of swordplay, Filipino escrima and some Caribbean and Central American machete practice for example, that parry with the flat. Notably, these weapons do not have guards, and if parries are not used sparingly, and made carefully, fingers will be lost (which is almost certainly why serious sparring and actual combat with these weapons is often either in “absence of blade” and emphasizes tempo actions, or involves grappling and other manipulations in order to control the adversary’s blade). However, the forms of cutting swordplay with Western battlefield weapons–saber, broadsword, backsword, hanger, cutlass–all show the use the of the edge for parrying in texts, illustrations, and other accounts. The objection is that a parry will damage the cutting edge. And so it will. But typically the forte is used for parrying, which is seldom sharp, and even if it is, is seldom used for cutting. Moreover, those who argue for the flat rather than the edge, in spite of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, forget one thing: each time the adversary parries your blade, it will be nicked. A blade is going to get damaged in combat. In fact, there are plenty of historical accounts of swordsmen proudly noting their “saw-toothed” blades as proof of just how desperate the combat was. It is also much easier to control a heavier weapon in the parry when parrying with the edge, and more powerful parries may be made this way.

THE TERMS HANGER VERSUS CUTLASS

In regard to the myth that ‘hanger’ was the sole term used to refer to the common cutting sword at sea–to the cutlass, in other words–in the 17th century, and that ‘cutlass’ was only an eighteenth century term, I’ve excerpted the following from a Mariner’s Mirror article I wrote a few years ago (“Eyewitness Images of Buccaneers and Their Vessels,” vol. 98, no. 3, August 2012). I added it to the original draft after a pre-publication editorial reader for the journal suggested I may have used the term cutlass in error. I had to prove I was correct.

From my article: “Still debated today are the issues of whether hanger or cutlass is the more appropriate English name for the short cutting sword or swords used by late seventeenth century mariners, and whether the words refer to the same or different weapons. Hanger and cutlass (also cutlash, cutlace) are each found in English language maritime texts of the mid to late seventeenth century. In some cases there appears to be a subtle distinction made between them; in others they are used interchangeably.

“The English 1684 Malthus edition of Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America refers only to ‘cutlace’ or, more generically, sword as the buccaneer’s arme blanche. There is also at least one reference in the Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, dating to the 1680s, associating the term cutlass with Caribbean pirates.[1] The 1684 Crooke and 1699 Newborough editions of Exquemelin refer to both hanger and cutlass, and use the terms interchangeably in reference to the sword of the notorious buccaneer Jean David Nau, better known as l’Ollonais. (Hanger once, cutlass twice, as well as a note that his men were armed with cutlasses.)

“It is possible that the description of l’Ollonais’s use of his sword to mutilate and murder prisoners may have given first rise to the reputation of the cutlass as the arm of the romanticized ‘cutthroat pirate’, a reputation enhanced by Charles Johnson’s pirate history forty years later, and then by Robert Louis Stevenson and other nineteenth century novelists. Even so, the cutlass already had a sanguine reputation, doubtless inspired in part by its descriptive, alliterative name: ‘by the bloudy cut-throat cuttleaxe of swaggering Mars’ wrote Thomas Coryate in 1611. By the eighteenth century, cutlass was the predominant English term for the seaman’s short-bladed cutting sword.”[2]

In the British colonies in America, the term cutlass was often used rather than hanger in lists of militia and trade arms as well: Caribs “well armed with new French fuzees, waistbelts and cutlasses” (August 3, 1689); “100 cutlasses” (Maryland, February 4, 1706); “100 cutlaces with broad deep blades” (Maryland, June 23, 1708); “2,000 cutlasses” (South Carolina, July 8, 1715). That said, some colonies used the term hanger instead in the same period. (All citations from the Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, America and West Indies.)

The earliest Caribbean reference to cutlasses I’ve found to date is in “The Voyages of Captain William Jackson (1642-1645),” a first-hand account describing Jackson’s most famous plundering voyage from one end of the Caribbean to the other: “The Armes delivered out to each company were, Muskitts, Carbines, Fire-locks, Halfe-pikes, Swords, Cutlases, & ye like offentius weapons…” Notably the term “hangers” is not used. English naval inventories of the 17th century tend to list “hangers” and “swords” as the two sorts of swords carried aboard, sometimes listing both, sometimes only one, confusing the issue. (And no, for the occasional “expert” who wants to argue, the term hanger in naval inventories at this time refers to short cutting swords, not sword hangers.) Worse, I’ve seen “swords and cutlasses” listed among the arms of various merchantmen. Almost certainly swords other than cutlasses and, among some officers, smallswords, were commonly carried aboard ship. Certainly they were aboard Spanish men-of-war, which had a large proportion of soldiers aboard: perhaps the earliest “Bilbao hilt” cutting sword, popular in the 18th century, dates to the 1660s and was found aboard a Spanish wreck. [See Sydney B. Brinckerhoff, Spanish Military Weapons in Colonial America, 1700-1821, regarding the Bilbao hilt. Jackson’s journal was published in Camden Miscellany vol. 13, 3rd series vol. 34, 1924; the quote refers roughly to September-October 1642.]

There are plenty of other seventeenth century references to the cutlass as the predominant maritime sword or term for maritime cutting sword, as opposed to the hanger: a July 1667 report of a Dutch descent on the English coast describes the attackers carrying muskets and with cutlasses drawn; there are at least two references in the papers of Charles II to Biscayners and Dunkirkers (privateers) assaulting English merchant captains with cutlasses; the 1682 inventory of the English merchantman St. Christopher of South Carolina included “ten swords & Cutlases;” mariner Robert Everard noted a cutlass among the arms of a dying French pirate who had boarded his ship, the Bauden, in 1686 (another witness referred to it as a scimitar, a generic term for a sword with a curved blade); the 1690s broadside ballad “A Satyr on the Sea-Officers” included the line, “With Monmouth cap, and cutlace by my side…,” clearly denoting its naval use; and witnesses to the fight between the Dorrill and the pirate ship Mocha in 1697 noted that the pirates were armed with “cutlashes”; and an authority-abusing Scottish captain, part of the Scottish expedition to Darien, was described thusly: “Capt. Drummond sent his men with drawn cutlasses on board a ship, Adventure, John Howell, master, and bade deponent, who was piloting her, to anchor her under the guns of his ship.” In the Deposition of William Fletcher, May 2, 1700, the said ship master described being his beating by pirates “with the flat of the Curtle-axes.” See also the endnotes below for other seventeenth century cutlass references associated with pirates and sea rovers.

It is quite possible that the distinction between cutlass and hanger was originally determined by the blades: a broad bladed weapon with a short blade length used by soldiers and seamen was originally defined as a “curtle-axe” (Shakespeare even uses the word) or cutlass, while one with a narrower blade was a hanger. Cutting blades heavy “at the tip” are excellent for cleaving cuts even at close distance: anyone who’s used a cutlass with such a blade for cutting practice will recognize this immediately, as will anyone who’s used a Filipino bolo knife. I’m speculating, of course, but the cutlass may have found preference at sea due to its greater ability at close quarters. Clearly, swords by both names were used, but the name cutlass stuck perhaps due to its greater efficacy.

This theory of cutlass versus hanger is supported by the French definition of coutelas from the 1694 edition of Le Dictionnaire de l’Académie française: “Coutelas. s. m. Sorte d’ espée courte & large, qui ne tranche que d’ un costé. Coutelas bien tranchant. coutelas de Damas. un coup de coutelas. il luy a fendu la teste de son coutelas, avec son coutelas.” That is, a kind of sword with a short wide blade, which cuts only one side. A 1708 Maryland arms list notes “100 cutlaces with broad deep blades” (cited above), suggesting that the term had become associated more broadly with short cutting swords in general.

Further, to those who still insist that “hanger” was the more common word, note that the 1678 English translation of Louis de Gaya’s treatise of arms does not translate “coûteau de chasse” as “hunting hanger” but as “hunting cutlass.”

It bears repeating that longer swords were often carried in addition to cutlasses, given that we find accounts of “cutlasses and swords” and “hangers and swords” in ship inventories (although the occasional ignorant Internet pedant, more often than not a re-enactor) will attempt to assert that the term hangers refers only to sword-belts.

An associated trivium is in order: the French term hassegaye (from Old French azagaie, Arabic az-zaġāyah, etc.) derives from an old word meaning “short spear,” and in the nineteenth century meant a short boarding pike. However, in the late seventeenth century it’s described as the word for the cutlass a ship’s captain wielded in action by holding it aloft, usually to inspire the crew as well as to intimidate the enemy. By waving it, the captain was demanding surrender, that is, ordering enemy colors and topsails “amain”–lowered, that is. “C’est un coutelas que le Capitaine tient en la main au bras retroussé pendent le combat.”

In any case, I leave you with a quote from a witness to de Ruyter’s raid on Barbados in 1665: “I did see him [de Ruyter] on the poope, with a cane in one hand, and a cuttle axe in the other, and as he stayed [tacked] I did see most part of his quarter carried away.” The cutlass may even have been the one whose hilt is depicted above. [From “A True Relacion of the Fight at the Barbados Between the Fort and Shipping There…,” in Colonising Expeditions to the West Indies and Guiana, 1623–1667,” edited by V. T Harlow (London: Hakluty Society, 1925). The “cane” was almost certainly de Ruyter’s long admiral’s baton.

MORE INFORMATION

For more information on the use of the cutlass at sea and ashore 1655 to 1725, in particular on its effectiveness as well as on its use in dueling, see The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth About Pirate Myths, chapter 8. (My publisher won’t appreciate my repeating the information here; by agreement I am not supposed to.) Both The Sea Rover’s Practice and The Buccaneer’s Realm also include information on the cutlass and other swords; the latter has an entire chapter devoted to associated late 17th century swords and swordplay. In sum, there’s a bit more information. For example, Bras de Fer missing his Spanish adversary and cutting through his hat instead, then tripping over a root as he attempted to renew his attack; the possibility of techniques similar to those used with the dusack (e.g. grazing and yielding actions in a single tempo); &c.

That said, I will add a note to dueling here even though far more information is in The Golden Age of Piracy (including the only confirmed description of a duel fought between buccaneer captains). Although it’s unlikely that duels were regularly, or even occasionally, fought aboard ships, for reasons and evidence discussed in The Golden Age of Piracy, it doesn’t mean there weren’t occasional affrays with swords aboard ship. Peter Drake, an Irish officer, one of the so-called “Wild Geese” who left Ireland after the defeat of James II, describes how in 1701, as he joined a Dutch regiment in Dublin and waited aboard a Dutch ship to sail to the Netherlands, “Among the recruits we had two prize-fighters, who, getting drunk, fell to quarrelling; the company declaring, each for the one whose cause he espoused, an uproar ensued, and several strokes were exchanged.” But this was a brawl more than anything else, and among soldiers, not seamen. Note that prize-fighters fought primarily with various swords, as well as with quarterstaff, and occasionally with fists. (Peter Drake, The Memoirs of Peter Drake [Dublin: S. Powell for the Author, 1755]. Stanford University reprinted the memoirs in 1960, edited by Paul Jordan-Smith.)

SUGGESTIONS ON PURCHASING REPLICA BUCCANEER CUTLASSES

If for whatever reason — historical research, reenactment, swashbuckling flair for your wall, modern piracy — you want a reasonably historically accurate cutlass replica, you’re sadly and mostly-but-not-entirely out of luck. There are only a handful of sword-makers who forge what can be termed historically accurate functional cutlasses, and they’re typically priced at US$500 to $1000 or more. Few typically have stock on hand; most are commissioned orders that may take months or years for delivery. Loyalist Arms stocks a small variety of cutlasses suitable to the era. Likewise, At the Royal Sword periodically stocks a few mostly historically-accurate cutlass and hanger replicas suitable to the buccaneer and early 18th century pirate eras. Cold Steel has a hunting hanger and a “pirate” cutlass that are suitable, if not as accurate as might be desired (although I like them both). In particular, the “pirate” cutlass is more of a dusack; removing the side rings would make it more appropriate to the buccaneer era. Even so, it is something of an homage to the shell hilt cutlasses of reality and Hollywood, a “sea beast” of a cutlass, yet with beautiful balance. CAS Iberia has a “shell guard cutlass” with a large outer shell and a much smaller inner shell tapering into a thumb ring. It’s the closest on the market to the cutlasses shown in the famous illustrations of Roc Brasiliano aka Gerritt Gerritson alias “Rocky” and the infamous l’Ollonois. It, the dusack, and the hunting hanger are quite functional and nice pieces for the price. Note that most cutlass replicas on the market are historically inaccurate, anachronistic, or pure fantasy (some have elements of all three); many are wall-hanger junk that could not be used for actual combat.

NOTES

[1] CSPC, 1681-1685, no. 1509. January 19, 1684. “A Relation of the capture of Providence by the Spaniards. On Saturday, 19th January, about 3 o’clock, Juan de Larco with two hundred and fifty Spaniards came down the harbour and landed at Captain Clarke’s, half a mile to east of Charlestown. Captain Clarke being out of doors near the waterside, some men in ambush shot him through the thigh and cut his arms with a cutlass, and then they marched away with all haste to the town, firing into some houses as they went…”

Another instance described in CSPC, 1677-1680, no. 1624. December 30, 1680, deposition of Robert Oxe.”The Spaniards killed two men and cruelly treated the deponent, hanging him up at the fore braces several times, beating him with their cutlasses, and striking him in the face after an inhuman cruel manner.” The Spanish pirate hunters were commanded by Captain Don Felipe de la Barrera y Villegas. Under his command were Juan Corso and Pedro de Castro, two captains noted for their reprisal cruelty against English and French seamen.

[2] Thomas Coryate, ‘Laugh and be Fat’ in Coryat’s Crudities (reprint London, 1776), vol. 3:n.p. Regarding foreign terms for cutlass, the original Dutch edition of Exquemelin’s work (1678) uses sabel (saber), as does David van der Sterre’s 1691 biography of Caribbean sea rover Jan Erasmus Reyning, but a 1675 English-Dutch dictionary notes kort geweer as the Dutch term for cutlass. Exquemelin’s Spanish edition (1681) uses ‘alfange’ (alfanje), whose root is the Andalusian Arabic alẖánǧar or alẖánǧal, from the Arabic ẖanǧar, a dagger or short sword, which some scholars have suggested is the origin of the English word hanger. The OED (2nd ed.) doubts this and derives it instead from the Dutch hangher. Although the Spanish connection to the Low Countries, and thus a connection to the Dutch term, appears suggestive, the English use of hanger predates Spanish rule. Alfanje is typically translated as cutlass, hanger, or scimitar. Exquemelin’s French editions (1686, 1688, 1699) refer to both coutelas and sabre, noting that flibustiers were armed in one instance with a good coutelas, in another a coutelas or sabre. Labat, describing the early flibustiers, notes each having a well-tempered coutelas among their arms. Most etymologists consider cutlass to be derived from coutelas. Saber, sabre, and the Dutch sabel derive from the German sabel, with authorities noting the term’s Slavic origin.

Regarding the various spellings of cutlass in the mid-seventeenth to early eighteenth centuries: cutlass, cutlace, cutlash, curtlass, curtelass, courtlass, courtelass, and curtle-axe are all common.

Copyright Benerson Little 2016-2018. Originally published December 31, 2016, last updated March 6, 2025.

Walking the Plank: An Associated Image

“Kapitein Lambert Hendrikszoon laat 125 zeerovers ophangen aan de ra’s van zijn schepen of in zee gooien voor de haven van Algiers, ca. 1619, Jan Luyken, 1682 – 1684.” (Rijksmuseum.)

In The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths, I’ve devoted an entire chapter to this myth of walking the plank. The image above is of a Dutch flotilla commanded by Captain Lambert Hendrikszoon circa 1619 harshly negotiating a peace treaty with Algiers, notorious for its “Barbary corsairs.” Note that a corsair was a privateer, not a pirate, although often the Barbary corsairs were referred to as pirates–after all, they were not “Christians.” Even so, they were lawfully commissioned and were pirates only if they went to sea without a commission to hunt prey. A major part of Barbary corsair plunder consisted of prisoners–Christians, often–taken as slaves. This was naturally an objectionable, heinous, barbaric (note the origin of the word) practice. Yet Europeans often hypocritically failed to note the irony that Barbary corsairs were enslaving people who themselves engaged in the slave trade of Africans, Native Americans, mixed races, and sometimes even of Asians–and, at least to the early 18th century, North Africans.

Detail. (Rijksmuseum.)

In the detail below, Algerine prisoners are being murdered in reprisal, in this case via “walking the plank”–but clearly no plank was necessary.

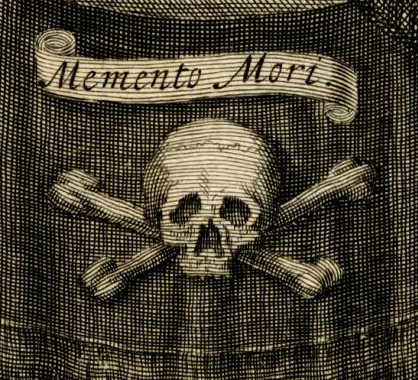

An Early Skull & Crossbones at Sea, and More

Invariably as one of my books is published, my continued research uncovers relevant information ranging from corrections to supplementary material. In the past I have posted this information in a pdf file, often quite lengthy, but for this book I intend to post on the book’s page (GAoP above) and also especially on this blog.

And for my first supplement, a painting by Jacob Gerritsz, mid-seventeenth century, of an allegorical ship representing the Holy Roman Catholic Church. The painting is intended as anti-Calvinist propaganda demonstrating that Calvinists and other “Reformers,” including Calvin himself firing a musket at the ship, cannot harm the Holy Church. One of the banners the ship flies is a skull and crossbones, the earliest I’ve seen to date. The flag is merely a symbol here, representing death, but could the painter have been aware of the flag flying for real somewhere?

“Das Schiff der Kirche” by Jacob Gerritsz, circa 1640 to 1649. Copyright DHM/Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht.

Probably not, for why would the Church depict a ship (one of decidedly Spanish design) representing the Church flying a pirate banner? This is hardly the message the Vatican would like to present as an argument against Calvinism. More likely would be Calvinism, in the Roman Catholic Church’s eye, flying the flag of piracy.

Detail from “Das Schiff der Kirche” by Jacob Gerritsz.

The fact is, although the skull and bones was used extensively as a mortuary symbol, and may have been flown at this time by some Barbary corsairs, it does not appear to have been regularly flown, with extensive attached symbolism, until the coming of the Anglo-American pirates in the early 18th century. Details, of course, are discussed in The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth About Pirate Myths.

The same black flag with skull and crossbones is similarly used in an allegorical poem of the early 18th century, prior to the American pirates who flew the skull and bones, to represent the banner of Charon, ferry-master of the Styx in Hades.

The death’s head in the painting above has a frightening three dimensional aspect, which would take a talented pirate to replicate with paint and brush. Most, we imagine–and we can only imagine, having no existing pirate flags from the Golden Age from 1655 to 1725, only written descriptions–would be simple fabric cutouts or simple painted images. However, in The Golden Age of Piracy I do discuss the flag of Jean Thomas Dulaien who sailed shortly after the period, for which we have a written description, as well as images of a purported drawing and of a purported woodblock made from the drawing. All are similar but none exactly matches the other. The original flag was reportedly destroyed on the order of Louis XIV.

Except for a skull and bones flown on a red field–a flag of no quarter–by French flibustiers in 1688, and perhaps before and after, we have no evidence of their use among pirates and other sea rovers of European origin until the early 18th century, the first in 1700, and the rest circa 1715 and afterward. They may have been in use prior to this time by some of the Barbary corsairs. Details can be found in the first chapter of The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths.

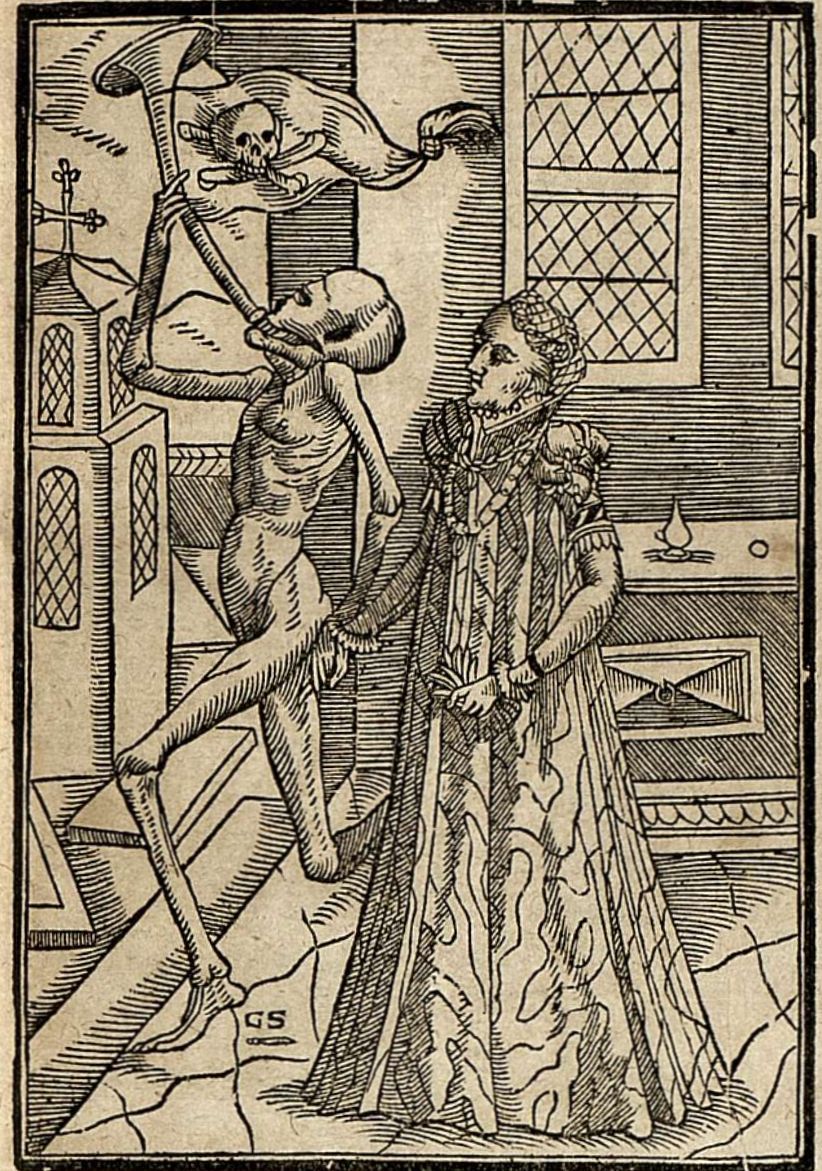

Banners with skull and bones have reportedly been around a long time, although depictions of them in art prior to the eighteenth century are difficult to find. Below is one by Hulderich Froelich of Basil, Switzerland, part of his 1588 Todtentanzes or “Dance of Death” series, one of which is Zwen Todentäntz, deren der eine zu Bern. Charles Hill, in his Episodes of Piracy in the Easter Seas, 1519 to 1851, published serially in the 1919 and 1920 editions of The Indian Antiquary, points this illustration out. Froelich’s “Dance of Death” along with others, is discussed in fair detail in here.

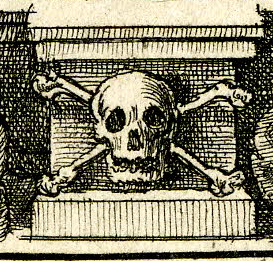

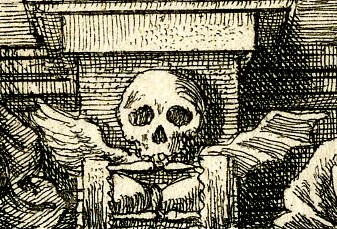

For the curious, what might the skull and crossbones, or skeleton, have looked like on real pirate flags of the early 18th century? We have only one likely authentic example of one, and it’s only a purported drawing of the flag of a French pirate, and of a woodcut believed to have been made from the drawing. More on them in a moment. The following are skulls and bones taken from a few late seventeenth century image showing various representations.

Detail from a portrait of Ernst Eberhard Friedrich, Count of Hohenlohe-Langenburg. Circa 1671. After Johann Georg Kreutzfelder, print made by Jacob von Sand. British Museum.

Detail from the Dance of Death series. After Abraham van Diepenbeeck (border), after Hans Holbein the Younger, print made by Wenceslaus Hollar. 1651. British Museum.

Detail from the Dance of Death series. After Abraham van Diepenbeeck (border), after Hans Holbein the Younger, print made by Wenceslaus Hollar. 1651. British Museum.

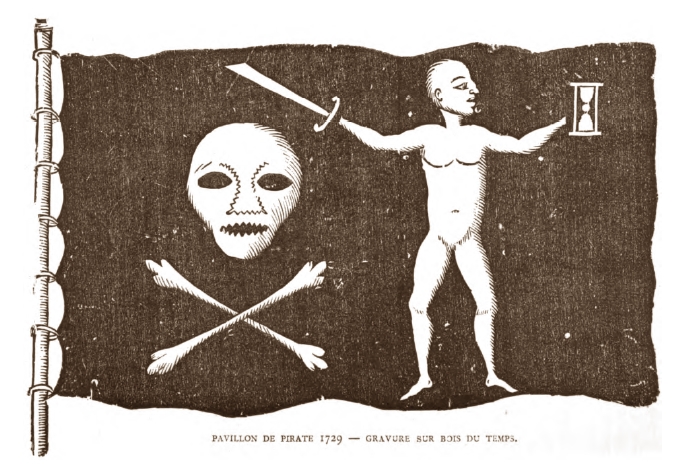

As for the one real “Golden Age” pirate flag we have an image of (there are no existing examples of real pirate flags from this era), it just barely makes it into the era, as at 1729 it’s late for the period that generally is regarded to end at 1725 or 1728. It’s also not the flag of a pirate of an Anglo-American pirate, but a French one, from France and returning to France. The pirate in question is Jean-Thomas Dulaien, whom I’ve discussed along with his flag in The Golden Age of Piracy. The first image below was reportedly created from the original flag, which was reportedly destroyed by order of Louis XIV; the second is of a woodblock or woodblock print made from the image.

The purported Dulaien original, copied from the actual flag. Clearly, if the image is accurate (there’s no reason to believe it is not), the skull, bones, and man with cutlass and hourglass was painted on. The original flag was, according to reports at the time, destroyed.

The purported woodcut image made from the original illustration. Clearly it is only a representation of the original image, and not an entirely accurate reflection.

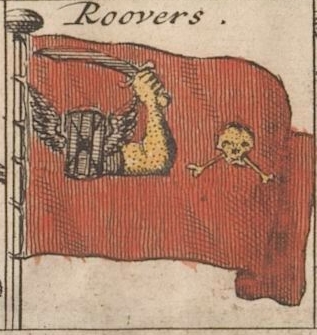

Likewise, since publication I’ve also identified earlier images of the red flags of the Islamic corsairs, one dating to 1711, the others probably 1707 to 1711. Clearly these sea-going flags were around prior to the Anglo-American pirates who used similar flags, as were others I’ve noted in the book itself.

Schouw-park aller Scheeps-vlaggen des geheelen Water-Waerelds, 1711. The flag is shown among Barbary and Turkish sea flags. This flag is popularly, and incorrectly, attributed to the pirate Christopher Moody. (Rijksmuseum.)

Ottoman corsair flag from Nieuwe Tafel van alle de Scheeps Vlaggen des Gehele Water-Waerelds op Nieus Vermeerdert en Verbeeterdt, probably dating 1707 to 1711, possibly slightly later, based on some of the English flags shown. The Rijksmuseum incorrectly dates it 1650 to 1700.

Algiers red banner with death’s head, from Nieuwe Tafel van alle de Scheeps Vlaggen des Gehele Water-Waerelds op Nieus Vermeerdert en Verbeeterdt, dated as immediately above.

And last, a note on the purported flag of Blackbeard. Historian Ed Fox has pointed out that, according to The Mariner’s Mirror (1912, vol. 2, no. 3) the horned Blackbeard flag first appears in The Book of Buried Treasure by R. D. Paine (Ralph Delahaye), 1911. The book was reprinted in 1981 by Arno Press. The drawing is fanciful but is based on a legitimate period description of a pirate flag. A later artist or publisher ascribed it, with minor modification emphasizing devil horns, to Blackbeard.

Copyright Benerson Little 2016-2018. Originally published December 19, 2016, last updated December 9, 2018.

The Authentic Eyewitness Image of the Real Buccaneer

The dashing image in the banner above–in which Peter Blood’s posed-for-the-camera attack has been parried by the equally posed Captain Levasseur, and Blood needs to recover quickly before he finds a blade in his eye or his belly–is taken from an original publicity still for Captain Blood, 1935, starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone. The film duel between Flynn and Rathbone, of clashing swords on California sand, is without doubt the most iconic of Hollywood sword fights, and although it has often been imitated, the results have almost never been quite as satisfactory. Certainly no other film “duel on the beach” is so evocative.

Therefore, in view of the foregoing, not to mention my long admiration for both the novel by Rafael Sabatini and its film version directed by Michael Curtiz, and as much for fun and nostalgia as for education, I’ll spend my first dozen or more blog posts working my way through authentic, literary, and film swordplay among pirates, with occasional associated digressions.

However, before we draw swords and explore the myth and reality of fencing with “sharps” among pirates and others, we’ll consider what the seafaring thieves of the 1680s Caribbean actually looked like, and how they were armed. Was this anything like Sabatini or Curtiz represented them? Was it anything like illustrators and Hollywood artists—Howard Pyle and Douglas Fairbanks, for example, whose works have come to define the image of the buccaneer—dressed them up and showed them off?

Fanciful illustration, “The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow,” by Howard Pyle, from “The Fate of a Treasure-Town” in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1906. Reprinted in Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

To begin, we require a few definitions. With a few exceptions, most of the Caribbean sea rovers from 1655, when England piratically seized Jamaica from Spain, to 1688, when Europe went to all out open war, existed in a gray area between legitimate privateering and outright piracy. At times these sea rovers had legitimate commissions, at times a mere “wink and a nod” from local authority, and at times no commissions at all, or forged ones, or falsely extended ones. In all cases these rovers eschewed the term pirate for two reasons: first, piracy was a hanging offense, and second, they considered themselves as something better than common pirates. After all, they not only attacked well-armed Spanish ships at sea, but they also, in military order, sacked Spanish towns.

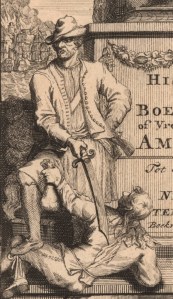

A somewhat more accurate illustration of a buccaneer threatening a Spanish prisoner, from the frontispiece to Exquemelin’s Historie der Boecaniers, of Vrybuyters van America, 1700. (John Carter Brown Library.)

Their preferred terms were, among the English-associated rovers, privateer and buccaneer. The former proclaimed their legitimacy, the latter their unique place. The term buccaneer derives from boucanier, the term for the French cattle and swine hunter of Hispaniola, which derives from boucan, a Tupi word meaning grill or grate for cooking and smoking meat and fish. (Similarly, barbecue derives from the Spanish barbacoa, which derives from the Taino word for the grill or grate.) The French-associated rovers, on the other hand, used the term flibustier, which, as far as we can tell, originated with the Dutch vryjbuiter, which was anglicized via a pretty much direct translation as freebooter, which the French adopted as fribustier and flibustier, which was later anglicized as filibuster. Occasionally the French used the term aventurier, or adventurer, which accurately reflected the men drawn from all walks of life to the trade. (For eyewitness images of boucaniers, go here.)