Home » Swashbuckling Literature (Page 2)

Category Archives: Swashbuckling Literature

The Duel on the Beach, Part II: The Black Swan (Updated!)

Perhaps the only swashbuckling novel whose narrative arc rests entirely upon the near-certainty of a duel at the climax, Rafael Sabatini’s The Black Swan epitomizes the duel on the beach: a desert isle and a ship careened; a pair of expert swordsmen who hate each other; a damsel’s safety, even her life, depending upon the outcome; an audience of pirates as Howard Pyle or N. C. Wyeth painted at their finest; and, above all, at atmosphere of tropical romance amidst danger.

Famed novelist George MacDonald Fraser, in his introduction to Captain Blood: His Odyssey (Akadine, 1998), referred to The Black Swan as “an almost domestic story of the buccaneers.” The only other novel to come close to such “domesticity” is Frenchman’s Creek by Daphne Du Maurier–but it has no climactic duel. (Fraser also described The Black Swan as “almost claustrophobic,” not as in insult but to point out that it takes place largely within the confines of a tiny desert isle.)

Even The Leatherneck magazine, a publication for United States Marines, noted in October 1932 that “the thrilling duel between Tom [Leach] and Charles [de Bernis] is one of the best pieces of description we have read in many moons.” Of all the pirate duels in literature it easily ranks as the finest. (Contrast this magazine with the Ladies’ Home Journal below: Sabatini had broad appeal.)

Let me note right now that (1) this blog post is not a review–I thoroughly enjoy the novel, it’s one of my favorite “summer” reads, especially at the beach–but more of an abridged annotation. Further (2), this post is divided in two sections: background and annotations, so to speak, regarding the novel itself, followed by a detailed dissection of a singular technique employed in the duel.

This post follows part one (the duel on the beach in fiction) and precedes part three (in film), part four (Flynn versus Rathbone in Captain Blood), and part five (in reality).

The first section has some spoilers, but not so many as might ruin the first-time reading of the novel. Even so, if you haven’t read the book, you might still to choose to read it now and then return here. And then re-read the novel, it’s certainly enjoyable enough to deserve a second time around.

However, if you haven’t yet read the novel, PLEASE DON’T READ THE SECOND PART ON THE DUEL ITSELF! Read the novel, then return. I’ll place a second warning just prior, just in case. Reading Part One of this Duel on the Beach series is also helpful but not required.

Background & Annotations

The Black Swan was based on a short story, likely written simultaneously with the novel itself, by Rafael Sabatini, called “The Duel on the Beach,” published in the Ladies’ Home Journal, September 1931. Sabatini’s short stories, excerpts, and “pre-novels” were published widely in both “men’s” and “women’s” magazines. “The Brethren of the Main,” upon which Captain Blood: His Odyssey was based, was serialized in Adventure magazine, for example, for a largely male audience.

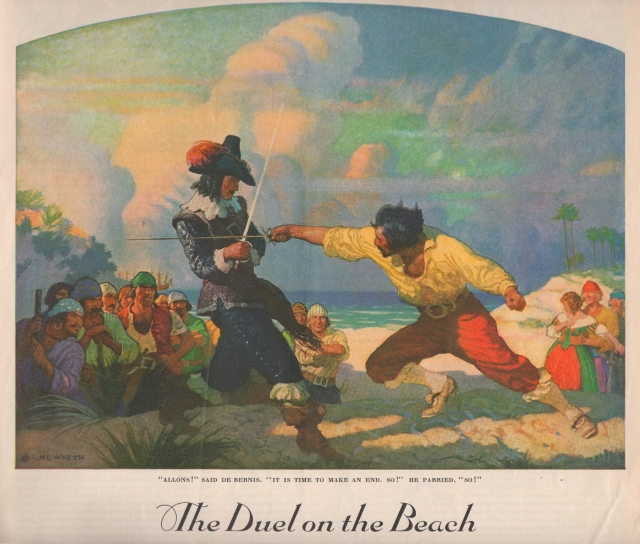

The Famous Wyeth Painting

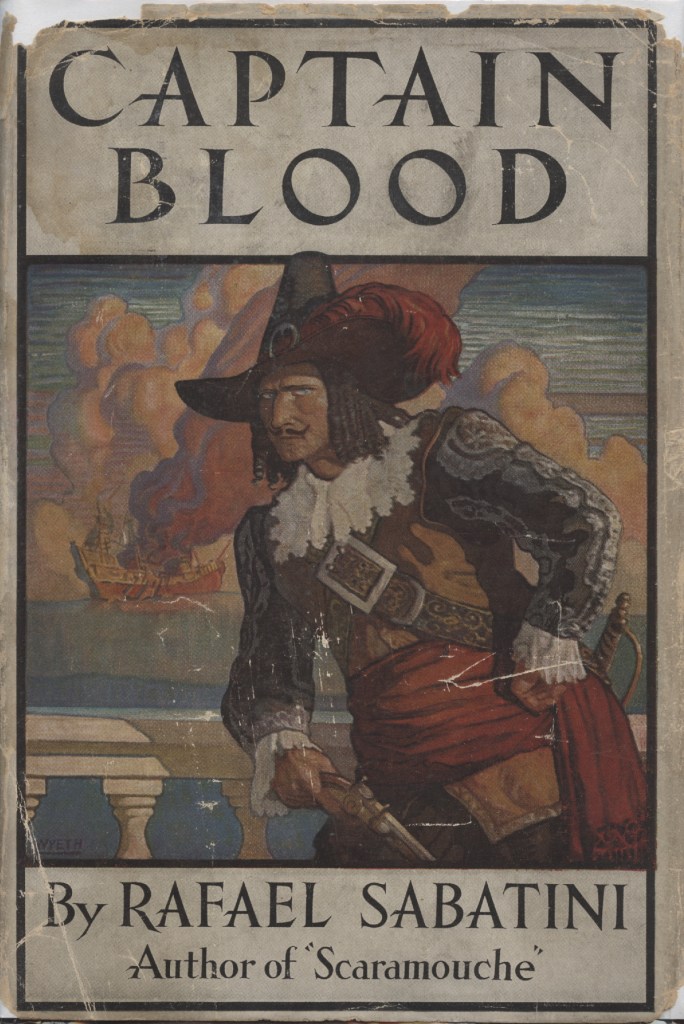

The novel is often closely associated with N. C. Wyeth’s famous painting, shown above and below, used on its US dust jacket. Secondarily, and unfortunately, it is often also associated with the 1942 film of the same name, which takes such extraordinary liberties with the novel as to be the same story almost in name only. The film deserves little if any further discussion here.

Wyeth’s painting evokes the action of the climactic duel, if not entirely accurately. The close parrying of hero Charles de Bernis and the animal-like aggressiveness of villain Tom Leach are graphically represented, but the actual technique of both depicted fencers leaves something to be desired for expert swordsmen. It’s more representative or symbolic than accurate, although–as I will be the first to point out–one could argue that the swordsman on the left may have just made a close, shortened parry as he stepped forward into an attack. But no matter, at least not for now.

More importantly, a couple of principal characters, whom we would expect to be in the painting, Major Sands in particular, are missing. Further, it is difficult to tell the color of the clothing of de Bernis on the left–is it the “violet taffetas with its deep cuffs reversed in black and the buttonholes richly laced with silver” (and apparently with claret breeches) which Sabatini early on confuses with a suit of pale blue taffetas worn by this “tall, slim, vigorous figure of a man”? De Bernis, for what it’s worth, wore the violet at the duel.

Still, the woman in the painting might be Priscilla Harradine, the love interest, wearing “lettuce” green as she does at all times, duel included, in The Black Swan other than in the opening scene, although the bright orange doesn’t fit. Further, the woman in the painting has the correct “golden” hair, and pirate Tom Leach, on the right, wears the scarlet breeches of his faded scarlet suit, as in the novel, including at the time of the duel.

Still, it’s not as accurate a representation of the novel’s duel as we would expect from a commissioned painting, even though most dust jacket and frontispiece art is often inaccurate.

And there’s a reason for this: the painting was commissioned neither for the 1931 story nor the 1932 novel. Rather, it was commissioned in the mid-1920s by Carl Fisher, a wealthy American entrepreneur. N. C. Wyeth completed the painting in 1926. Two of Fisher’s friends are depicted as pirates watching the duel, one of whom is John Oliver La Gorce of The National Geographic Society (more details here) and into whose hands the painting passed, and from his eventually to the Society.

Some suggestions have been made that Sabatini may have written the duel scene to somewhat correspond to the painting. This is entirely possible, but I don’t think it is necessarily so except in broad strokes, as we’ll see momentarily, and also later in the discussion of the duel itself. The trope of pirate duels on the beach leads all of them to look much alike, in other words, thanks in large part to Howard Pyle. (See Part One for other examples.)

The positions of the swordsmen in the “Duel on the Beach” painting are almost identical to those in an earlier N. C. Wyeth work shown immediately above, also named, or at least captioned, “The Duel on the Beach.” Wyeth painted it for Westward Ho! by Charles Kingsley (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1924), a swashbuckling romance of Elizabethan privateering.

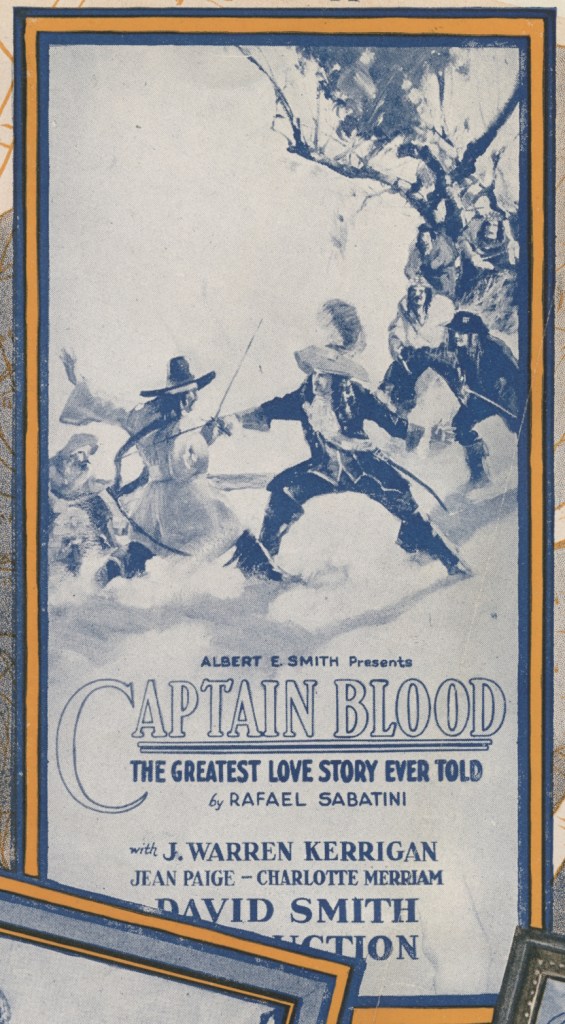

The parrying fencer in the 1924 Captain Blood poster above, artist unknown, is strikingly similar to that painted by N. C. Wyeth the same year for Westward Ho! and was probably influenced by Wyeth’s painting. Note the similarities to Wyeth’s 1931 painting used for the dust jacket and frontispiece of The Black Swan.

I strongly suspect Wyeth’s later “generic pirate sword-fight on the beach” painting that become the cover of The Black Swan was originally intended, at least in part, to suggest the duel in Captain Blood: His Odyssey. The clothing of the figure on the left might even be the “black with silver lace” of Captain Peter Blood.

Wyeth’s dust jacket and frontispiece for Captain Blood: His Odyssey, shown below, bolster my argument, as do the two single lines describing the duel in it [SPOILER ALERT]:

“It was soon over. The brute strength, upon which Levasseur so confidently counted, could avail nothing against the Irishman’s practised skill.”

Even so, again there are details lacking that we would expect: the buccaneers are not divided into two groups representing the two crews (Blood’s and Levasseur’s); Cahusac and the pearls-before-swine do not figure prominently among the spectators; Governor d’Ogeron’s son is missing; two ships rather than one show up in the background (the Arabella was anchored out of sight); and most importantly, Mademoiselle d’Ogeron and her lustrous black hair is missing–as already noted, the woman in the painting has blond hair.

Even more to the point (pun half-intended), perhaps Sabatini re-clothed his hero from sky blue to violet to match the painting–and then he and his editor forgot to correct all instances. It wouldn’t be the first time harried writers and editors have let errors go uncorrected.

Thus, at best, in spite of my best hopes and desires, the painting may have merely been inspired to suggest the duel in Captain Blood. The original “Duel on the Beach” painting, by the way, an oil on canvas 48 by 60 inches, was sold at auction by Christie’s in 2012 for $1,082,500.

The Duelists: Charles de Bernis & Tom Leach

The novel’s hero is Charles de Bernis, former buccaneer and close companion of Henry Morgan. Sabatini biographer Ruth Heredia, author of Romantic Prince: Seeking Sabatini and Romantic Prince: Reading Sabatini, considers the character to be ultimately an iteration of Captain Peter Blood, probably Sabatini’s favorite of all those he created.

De Bernis is more or less a French gentleman, if a bit of a fortune hunter or adventurer originally, which all flibustiers by definition were. And indeed a fair number of flibustier leaders were gentlemen, most notably Michel, sieur de Grammont, who played so commanding a role in many of the great French buccaneering actions of the 1680s. Others included Raveneau de Lussan who wrote a journal documenting one of the great South Seas buccaneering expeditions; the sieur d’Hulot, veteran of two campaigns against Algiers and the Algerine corsairs, who would later command the regular French forces on Saint-Domingue; the sieur de Chauvelin who died in battle during a failed reconnaissance of Matanzas prior to an ultimately aborted attempt on St. Augustine; and many more.

Barring the boots Sabatini and so many authors of his era dress buccaneers in–a trope or myth, there were no horses to ride aboard ship, thus no need for boots of “fine black Cordovan leather,” nor any evidence that seamen, including buccaneers, wore them–Charles de Bernis in real life would have otherwise dressed much as the author described him.

The image above is a near-perfect fit for Charles de Bernis. Please note that the cavalier is wearing “stirrup hose,” not boots. Stirrup hose was variously popular from the 1650s in the Netherlands to as late as the 1680s in parts of Spanish America. In France, it seemed largely, if not entirely, out-of-style circa 1680, and de Bernis likely no longer wore it.

Sword-belts were also common by this time, although many gentlemen did still wear baldrics as Sabatini’s hero does, of purple leather stiff with silver bullion. That said, eyewitness images of 1680s buccaneers (they do exist, I discuss them here) shows sword-belts, not baldrics. But this is a mere quibble.

So perfect is this illustration that I suggested it to Firelock Games (likely with the fictional Charles de Bernis in the back of my mind), and Miami artist Peter Diesen Hosfeld then used it as the basis for the French flibustier commander for its tabletop war game Blood & Plunder.

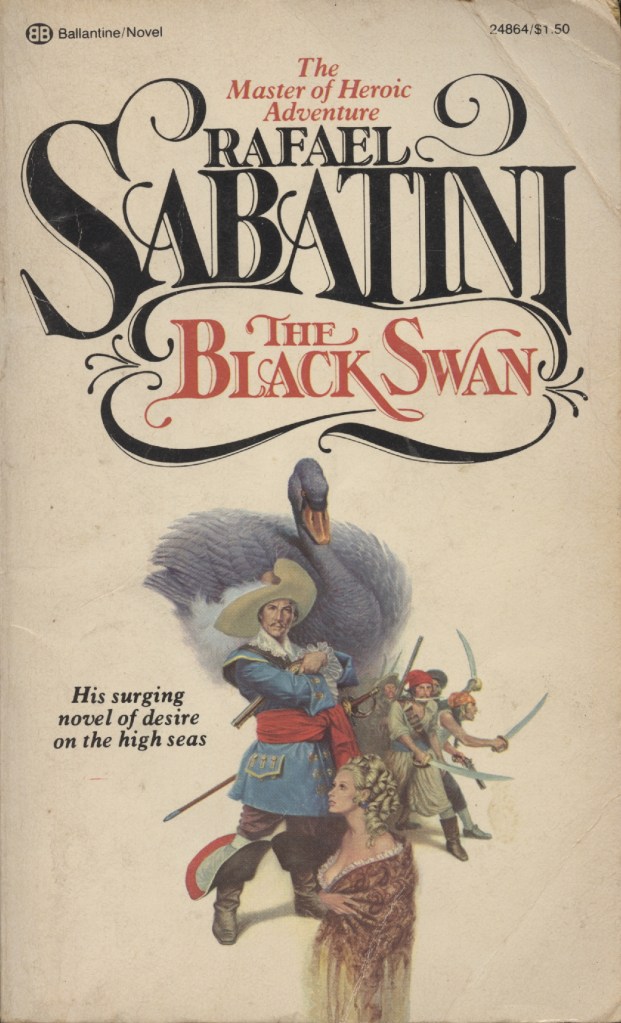

Popular illustrations and covers for the novel are rarely accurate, although this one for the 1976 Ballantine Books mass market paperback (the first I read, in fact), comes closer than most, and could have taken its inspiration from the author’s description along with images such as the one above:

As for red-suited Tom Leach, the villain, his name and something of his character may have been inspired by the fictional Captain Edward Leach of the East India Company, who out of greed betrayed his fellow passengers to pirates, and was, in poetic justice, murdered by the same pirates. Captain Leach, a fictional character, was invented by artist and author Howard Pyle in The Rose of Paradise (1887/1888), his first pirate novel.

However, there are two likely authentic 1680s candidates for his inspiration, both of whom Sabatini, an avid researcher, was probably aware of, given that their exploits are well-documented in the Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies.

The first is Joseph Banister, an indebted English sea captain turned pirate who slipped away at night with his 36-gun Golden Fleece, a former merchantman, under the cannon of the forts at Port Royal, Jamaica, escaping with little damage due to his surprise flight. But his piratical adventure would be relatively short-lived.

In June 1686 while careening his ship at Samana Bay, Hispaniola he was discovered by the pirate hunters HMS Falcon and HMS Drake. The men-of-war expended nearly all of their powder pounding the pirate ship to pieces. Banister’s temporary shore batteries (which [SPOILER ALERT] Tom Leach should have erected at the Albuquerque Keys) returned fire but failed to stop the men-of-war.

His ship lost, Banister and a few of his crew set sail with the French flibustier crew of a nearby flibot (the French term for a small flute) of one hundred tons and six guns. Parting soon afterward aboard a captured sloop, Banister was soon run to ground by the Royal Navy and hanged from the yardarm of the HMS Drake in sight of Port Royal, Jamaica in 1687.

As a noteworthy aside, the flibustiers Banister briefly consorted with soon set sail for the South Sea (the Pacific coast of South America), plundering until 1693 and leaving behind a journal of their escapades. In 1688, while attacking Acaponeta, Mexico, these French pirates unfurled a red flag of no quarter–the pavillon rouge, the pavillon sans quartier–of special interest: the red flag bore a white skill with crossbones beneath, the only instance of the skull and bones being flown by late seventeenth century buccaneers or flibustiers. It is possible, even likely, though, that it was flown at other times as well.

However, no matter his piracies, Banister was nowhere near the villain that Tom Leach is. Leach murdered captured crews, but not so Banister. But there was a 1680s pirate villain who was a closer match to Leach in villainy: Jean Hamlin, or more correctly Jean Amelin whose real name was Pierre Egron.

In desperate need of extra time for numerous projects, I’ll cheat and quote, with some paraphrase and revision, from the original draft of The Buccaneer’s Realm (Potomac Books, 2009), along with some added details from the Dictionnaire de Flibustiers Caraïbes by Jacques Gasser:

In 1683 Hamlin, a Frenchman commanding two sloops, captured the merchantman La Trompeuse (The Deceiver) from a French Huguenot, conman, and thief named Paine, and embarked on a piratical rampage. Or so goes the version of the story in English records. In French records, Hamlin inherited the ship from French buccaneer Nicolas Amon, known as Grénéze, when he gave up command in order to command another vessel on a voyage to the South Sea.

Amon had captured La Trompeuse, 200 tons and 16 guns, at the Isle of Roatan. Originally a French merchantman contracted to ferry soldiers, poor young women destined to become wives, and sundry goods and supplies to Cayenne, it was commanded by a Pierre Pan, a French Huguenot (Protestant). Learning of the first dragonnades in France — Louis XIV ordered dragoons quartered on French Huguenots in order to harass them into turning Catholic — Pain took the ship from Cayenne to Barbados, then to Jamaica where he contracted it to English merchant traders.

Hamlin set sail on a brutal voyage or outright piracy. He soon captured an English ship, informed the crew he was a pirate–not, mind you, a buccaneer or flibustier–, tortured some of the crew, impressed some, plundered the ship, and let her go. He soon captured several other English vessels, then sailed to the Guinea Coast and captured eleven slavers and three boats, plundering them all.

At Cape St. John the pirates divided the spoil, and, quarreling, separated into two companies, part remaining with Hamlin, part choosing to serve under an Englishman named Thomas Morgan (no relation to Sir Henry and probably a false name). Hamlin’s usual tactic was to fly an English Jack and commission pendant as if he were an English man-of-war, come alongside as if seeking a salute, and fire a broadside. Indeed, Hamlin’s strategy and tactics were identical to those of the early eighteenth century Anglo-American pirates who flew the black flag: attack weaker merchantmen, preferably by ruse. Most significantly, Hamlin and his crew referred to themselves openly as pirates, not buccaneers, filibusters, or “privateers.”

Hamlin was noted for torturing prisoners and otherwise brutalizing them, and for cutting men down “left and right” when he boarded ships. The violence often seemed in retaliation for any resistance.

Throughout his piracies he was protected by the corrupt Danish governor of St. Thomas, although after one return to St. Thomas, the HMS Francis entered the harbor and burned his ship in spite of being fired upon by the Danish fort. Some of Hamlin’s ship-less crew volunteered to serve Captain Le Sage, others Captain Yanky (Jan Willems). Soon enough, the governor of St. Thomas sold Hamlin a sloop with which he reportedly captured a Dutch frigate of thirty-six guns, renamed her La Nouvelle Trompeuse (the New Deceiver), manned it with sixty of his old crew and sixty new men, and continued his depredations. Some claimed that the ship was outfitted in New England, a colony well-noted for its Protestant piety and hypocritical support of piracy.

Other sources indicate that the ship was instead Hamlin’s consort, the Resolution commanded by Thomas Morgan. The ship had been chased aground at St. Thomas by the HMS Francis, whose crew cut its masts down and abandoned it. Hamlin soon refitted the frigate and sailed south, plundering mostly small prizes along the coast of Brazil. At one point, in a fit of rage and revenge, he cut the nose and ears from a captured priest, forced him to eat them, then murdered him. Or more likely, a sadistic crewman who acted as chief torturer — René Marcart, known as Vaujour, along with his assistants “La Fontaine” and Guillaume Belhumeur — did the deed while Hamlin supervised.

Some of his crew were so appalled at this abuse of a priest that they quit the ship in Cayenne. One of them, Jean le Mont, slipped away from Cayenne to Dutch Suriname — and was hanged for piracy. Four others who made it back to St. Thomas, including forced surgeon Samuel Beloth, made a similar mistake of sailing to Dutch Suriname where they thought they might lead a better life than at St. Thomas, and escape charges of piracy as well. The three pirate seamen were hanged for piracy and Beloth was forced to serve as a surgeon without pay indefinitely.

In his final act of piracy Hamlin had captured a small Portuguese ship and carried her into St. Thomas where he forced some of her Dutch crew to serve with him, even as the governor of St. Thomas forced some of the captured crew to draw lots and hanged the losers. Hamlin, who can rightly be called the first of the true pirates of the Golden Age — only the black flag was missing — was never captured.

In fact, he settled at St. Thomas, that Danish slave colony (they were all slave colonies, but St. Thomas was settled by Denmark specifically to profit from the slave trade) and occasional pirate haven, under his real name, and until his death owned a cacao (chocolate) plantation and raised a family with his wife, Barbara Rambert, who bore him three children.

Make Hamlin an Englishman, and not quite as lucky, and we almost have Tom Leach.

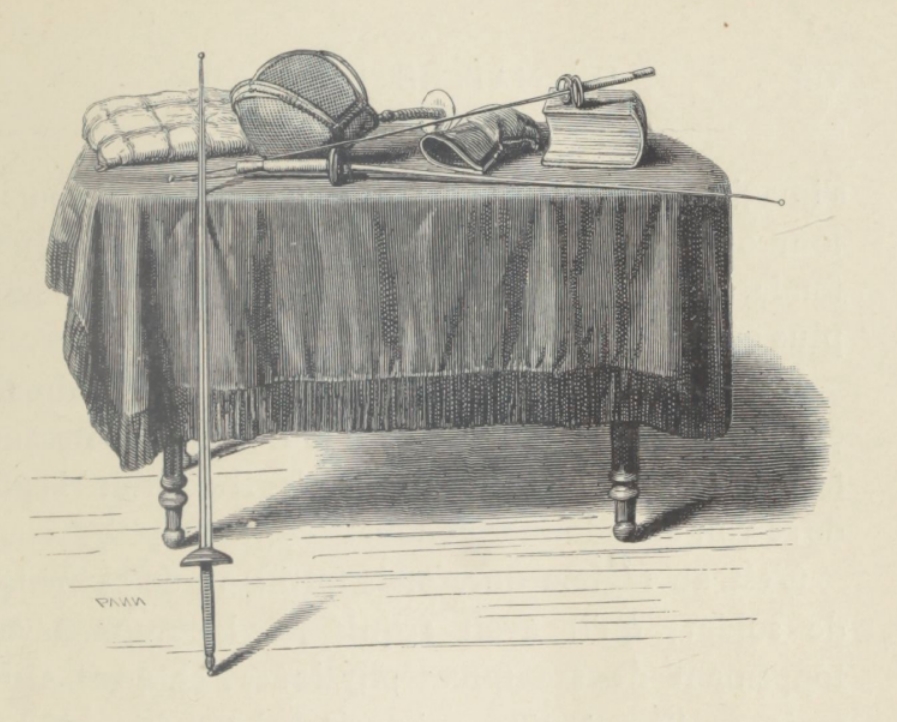

The Swords: The “Rapier” aka The Smallsword

In the novel, the duel is fought with rapiers. This is mildly problematic, as by this time the true rapier was still carried only Iberians–Spaniards and Portuguese–and by some Italians in areas under Spanish rule. The smallsword, with its shorter, lighter blade and smaller hilt, was the common dueling sword among gentlemen and those so pretending.

However, word usage comes to our rescue: Sabatini’s “rapier” remained in use in the British Isles as a word for smallsword. In fact, the English tended to refer to the Spanish rapier as a “spado,” from espada.

Although the cutlass was the common sword of late 17th century mariners, there are a few accounts of those who carried smallswords. Given that Charles de Bernis is something of a gentleman, and Tom Leach prides himself on his swordplay, we can imagine the duel, historically and realistically, as Sabatini described it.

[BRIEF SPOILER ALERT!] Charles de Bernis prepares for the duel by secretly practicing with the pompous Major Sands. In the book, the men use their real swords for practice, each with a pear-shaped wooden tip added to blunt the weapons. This is historically inaccurate, and almost certainly Sabatini, with his experience of fencing, knew this, but went with a simple plot device instead to keep the narrative clean and simple.

Read sword blades were never intended for practice with blade or target contact. They are tempered differently than practice blades, the latter of which are designed to flex many times before breaking, as well as to flex in order to take up some of the energy when hitting.

Real blades were and are usually much stiffer in order to maximize penetration–a too flexible blade might not penetrate thick clothing, cartilage, or otherwise deeply enough to cause a serious wound. Further, the use of real sword blades for practice will severely nick the sharp edges (if sharpened–not all smallsword blades were, but the nicks will still eventually damage the integrity of the blade) and significantly increase the risk of breaking a blade. In other words, such practice will ruin a fighting sword blade.

Practice swords called foils were used instead of real thrusting swords, and there were several styles in use at the time. The French “crowned” style was prominent in many schools. Pierre, the servant of Charles de Bernis, could easily have hidden the foils beforehand, making the scene more historically accurate. Hopefully the island was large enough, or the pirates busy enough, not to hear the clash of steel on steel–it travels far and there is no other sound quite like it.

The Dueling Ground: Maldita Key

The duel and much of the rising conflict leading to it takes place on the northernmost of the two Cayos de Albuquerque while Tom Leach’s pirate ship the Black Swan* is being careened there. The islands do exist, although their geography doesn’t entirely match that described in the novel, which for reasons of plot must take certain liberties. It might also have been quite difficult for the author to get accurate details of these small out-of-the-way keys.

There is, however, plenty of beach for dueling on the real island.

Located off the Mosquito Coast of Nicaragua and Belize south of Santa Catalina (Providencia, Old Providence) and San Andres Islands (roughly twenty-five miles SSW of the latter), the two small principal Albuquerque keys are actually part of Colombia (with a small military presence on the north key). The keys are ringed with reefs: technically, the islands are part of an atoll with a large lagoon at its center. Some old English charts list them as the S.S.W. Keys. The keys are roughly 250 to 300 yards apart, and Cayo de Norte is perhaps 200 yards across. Passage to its anchorages is difficult. Both keys are covered in coconut palms.

Cayo del Norte, where the action takes place, is named Maldita Key in the novel, meaning cursed or damned, probably a name of Sabatini’s creation given that I’ve not found the name referenced anywhere else. This isn’t the only time he invents or changes a place name. Similarly, Sabatini has imagined the island as larger, with higher elevations in places than the roughly 7 feet maximum elevation of the real island, and with a hidden pool of fresh water large enough to swim in.

Having once lived on Old Providence Island until the Spanish sacked it and forced the interloping settlers from it, buccaneer Charles de Bernis would have been familiar with the keys to the south.

The Duel Itself

LAST WARNING! SPOILER ALERTS! If you haven’t yet read the novel, you should stop, read The Black Swan, and then return.

The duel as described by Sabatini is about as well-written as a sword duel can be: exciting, well-paced, and largely rooted in reality. As such, I’m not going to comment further except to discuss and dissect the singular unconventional technique used by Charles de Bernis to kill his adversary.

Several years ago in a long-running conversation with Sabatini biographer Ruth Heredia as she prepared her second volume, Romantic Prince: Reading Sabatini, we had numerous discussions about swordplay in his novels. One point of discussion was what the de Bernis technique might actually have been.

I was never satisfied with the answer, discussed below, I gave her. Then one recent evening, while rereading the duel as part of some research into my annotations for Captain Blood, the answer struck me. I realized I had been mistaken in every analysis I’ve done on the duel, and knew immediately what de Bernis had done—and where Sabatini almost certainly found his inspiration. It was right under my nose all along, a purloined technique lying literally in plain sight for two decades or more, but my mind had categorized it such that I had not yet made the connection. Please excuse my excitement and fencing vanity as I make my argument.

For what it’s worth, this separate blog on The Black Swan was inspired by a recent long e-letter to Ruth Heredia on the subject.

The pertinent details: at the end of the duel, Leach makes a sudden and sneaky (sudden and sneaky are expected in swordplay) long low lunge in the “Italian” style, snake-like, with one hand supporting him, to slip under the guard of de Bernis. This was in fact both a French and Italian technique in the late 17th century, although by Rafael Sabatini’s era it was largely confined to the Italian and was generally considered as such. Sabatini notes in the novel that no “direct” parry could deflect this attack once fully launched. (Strictly speaking, a direct or simple parry is one made by moving the point and hand more or less in a direct line horizontally, as opposed to a diagonal, half circle, or circle.) While this may not be entirely true (see below and also the note at the end of this blog), a very low attack like this is quite difficult to parry, making an esquive (see also the discussion below) of some sort highly useful in defending against it.

Further, an attack made with the body and hand so low can only have as its torso target the lower abdomen or the groin, making it a ruthless, dishonorable attack when this is the intended, as opposed to accidental target — an attack suitable to Tom Leach’s venomous character.

As Leach lunges, de Bernis disappears from the line of attack. “Pivoting slightly to the left, he averted his body by making in his turn a lunging movement outward upon the left knee.” It was a “queer, unacademic movement” that “had placed him low upon his opponent’s flank.” De Bernis then passed his sword through Leach.

We require six conditions for the answer:

- A pivoting movement that averts the body.

- It must outward upon the LEFT knee (we assume almost assuredly that de Bernis is a right-hander).

- It must be a “queer, unacademic movment.”

- It must place him low upon his opponent’s flank.

- It must put de Bernis in position to pass his blade “side to side” through Leach.

- It must require TWO tempos, one for the pivoting movement, and one for the thrust into Leach’s flank.

As already noted, I was never satisfied with any conclusion I’ve come to. Of course, it could be that Sabatini left his description somewhat vague on purpose, and I’ve considered this as a possibility. However, my best guess was some form of intagliata, a term used by some nineteenth century Italian masters for an “inside” lunge off the line. In other words, if you’re a right-hander, you lunge toward the left, or inside, removing your body from the direct line of attack or riposte and placing yourself upon your adversary’s flank.

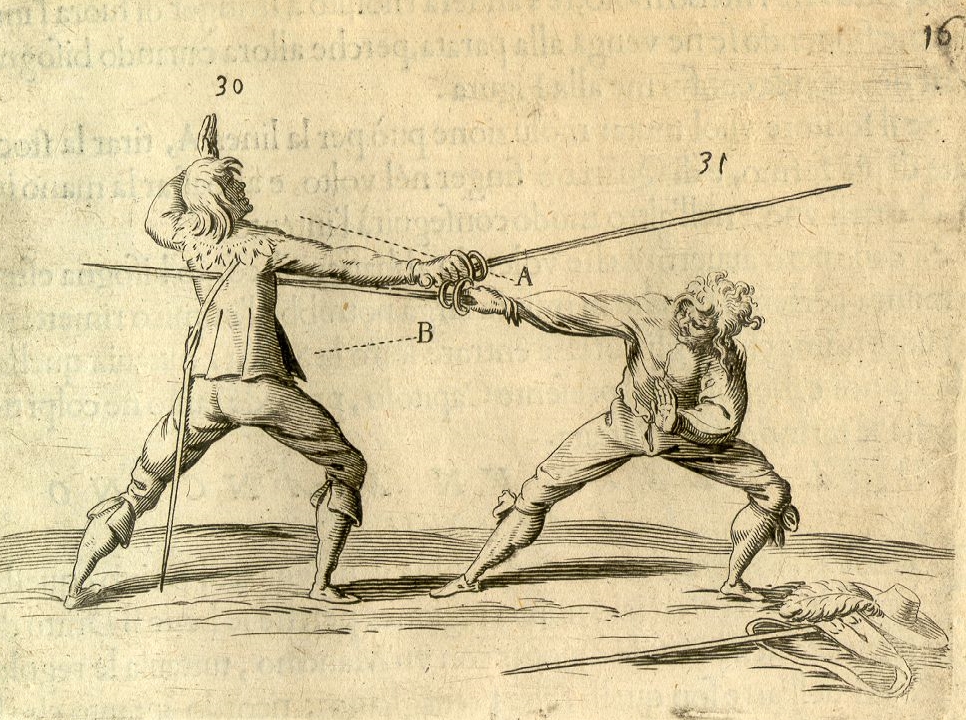

by Cesare Enrichetti, 1871. the fencer on the right has lunged off the line to the left in order to avoid his adversary’s blade.

The intagliata is a member of a group of techniques known in French as esquives, or in English, dodgings or body displacements for lack of more elegant expressions. The two principal esquives are the inquartata and the passata soto, both of which are primarily used as counter-attacks in a single tempo, designed to avoid the adversary’s attack while simultaneously thrusting, preferably in opposition (closing the line to prevent the adversary from hitting) or with bind (pressure on the adversary’s blade to prevent it from hitting) and removing the body from the line of attack.

They may also be used in two tempos, parrying and displacing in the first tempo, and riposting in the second. Single tempo counter-attacks without esquive often result in double hits, even when opposition is attempted, for the fencer often fails to predict the correct line or uses inadequate opposition. Body displacement increases the protection. It’s a backup, in other words.

Other esquives include the cartoccio or forward lunge while lowering the upper body; the rassemblement or very old school “slipping” as it was called; the “pass” or crossover forward bringing the rear foot forward in front of the lead foot; the simple backward lean; a lunge forward to the inside with rear foot (arguably a form of the pass); the various leaps or voltes to the side noted by some late 17th and early 18th century masters (seldom used now due to the narrowness of the fencing strip); and the lunge to the outside (to the right for a right-hander) off the line. My personal preference for dealing with Leach’s style attack is to retreat with a crossover (lead leg passing behind read leg) — if possible — while counter-attacking to the head (and, in historical weapons, using the offhand to attempt a parry), or making a hard low-line parry (see the technical note at the end). Note that if attacked in tempo as one advances, this is a difficult attack to counter without also getting hit.

I considered and even tested all of these. None entirely met the conditions. In particular, none were considered then as un-academic, although it could be argued that the leaps to the side are considered so today and likewise in Sabatini’s era. But the leaps met few of the other conditions. Compounding the problem was Sabatini’s use of the word “outward” which I, with 46 years fencing and studying swordplay of the past and present, and 26 teaching both, took at first to mean “outside,” which in fencing terms means, for a right-hander, to the right. In fact, Sabatini appears to have meant the word conventionally–outward rather than inward. One problem solved!

Yet the major problem still remained. In the 1935 film version of Captain Blood there is one option depicted, probably drawn by famous fencing choreographer Ralph Cavens (take note!) from an interpretation of The Black Swan is my guess — a volt to the left with the leading right foot, followed by the rear — but this too is actually an academic movement, a form of intagliata, again really nothing more than “lunging off the line.”

I remained distracted by the question: what other possible, conceivable two tempo movement — a pivot and lunging movement outward upon the left knee, followed by a thrust, probably via a lunge — would fit? What esquive could it be if not an intagliata? What might work yet be unorthodox? Importantly, what might be documented — not imaginary — in this category? In other words, how did Sabatini develop this scene, what was his inspiration?

I think almost certainly right here:

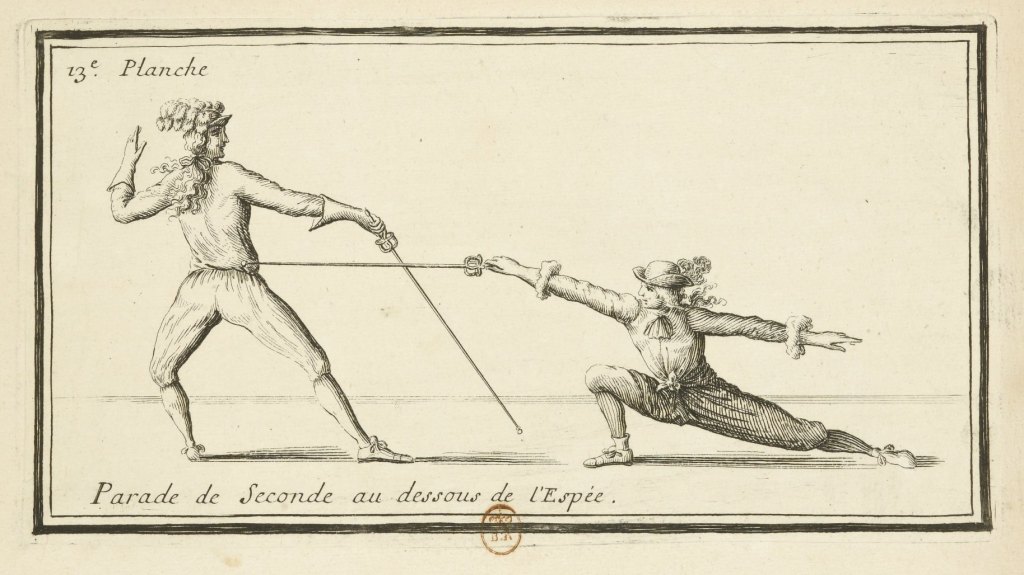

On the right a swordsman has made a very long low lunge. His hand is not on the ground as it commonly was, but this is immaterial. On the left is a swordsman slightly off the line, bending inward slightly, WITH HIS LEFT (REAR) LEG BENT IN A SOMEWHAT LUNGING MANNER.

This left fencer’s position appears bothersome to fencers not well-versed in fencing history (most aren’t, in fact). What does it depict? It might well be just a lean backward onto the rear leg to avoid a sudden low attack, or a failed retreat — the 17th century French school advocated keeping most weight on the rear foot, forcing most retreats to be made by crossing over, front foot moving first to the rear, passing the rear foot en route. (In fact, a parry combined with a crossover retreat is perhaps the safest counter to a long low lunge.) Or, it might be something more conventional, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

What’s important is what Rafael Sabatini might have thought it was!

Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that it depicts a fencer who has just pivoted off the line slightly in a lunging fashion in order to avoid a long low attack, as described by Sabatini. If so, to execute this, de Bernis need, as described, only pivot slightly to the left on the right or lead foot as he simultaneously leans back into a lunge on the left leg. This places him out of the direct line of attack and also out of range — and he has a tempo to do this as the low attack is made.

In fact, the parry shown in the detail above is a natural one against a long low attack, and would help protect de Bernis as he made his next movement, by providing some opposition — but it would almost certainly not have stopped the attack, or at least such conclusion might be drawn from the image. The exceptionally low attack might easily “force” most parries, as it has here.

In other words, parrying with the hand held at the usual height of the en garde position makes it difficult to apply forte (the strong third of the blade nearest the hilt) against the middle or, preferably, foible (weak third of the blade at the tip end), so necessary for an effective parry. In the detail above, the foible or middle of the parrying blade has been applied against the forte of the attacking blade, rendering the parry largely useless. It is likely that Sabatini’s statement to the effect that there is no direct parry that can stop such an attack once fully launched was inspired in part by this image. (See the technical note at the end of this blog for more detail, including on at least one unconventional parry that can deflect such an attack.)

But let us return to the unusual esquive. Because Leach is now subsequently off-balance — for a full second, fortunately — de Bernis has a second tempo in which to run him through, almost certainly with a conventional lunge. In fact, such long low lunges have a distinct disadvantage: they’re slow to recover from conventionally, that is, to the rear, leaving the fencer in danger. Likewise, if the fencer recovers forward, he (or she) may be at dangerously close distance. As well, poor balance is typical of this long lunge although there are some rare fencers who can manage it well, at least on hard floors.

Importantly, does the technique of Charles de Bernis work?

I’ve tested it — and it does! It is also historical, it is also unorthodox — and its imagination by Sabatini from the drawing, brilliant. It would only require that the fencer using be familiar with lunging with his left leg — having experience fencing left-handed, in other words, would help. And a fair number of fencers, although probably not a majority, did practice at times with the off-hand.

In fact, if the technique were deliberate, it would fall into the category of “secret thrusts,” which were nothing more than legitimate, if unorthodox, technique that was known to a minority of fencers and masters and was useful only in rare circumstances. And once it’s found useful, the unorthodox becomes the orthodox, in everything, not only in fencing.

The inspiring drawing is by Louis François du Bouchet, marquis de Sourches (1645 – 1716), circa 1670. The small collection of his drawings is well-known to historians of seventeenth century France. More importantly, there are some thirteen volumes of his memoirs, dating from 1681 to 1712, first published in the late 19th century: Mémoires du marquis de Sourches sur le règne de Louis XIV, publiés par le comte de Cosnac et Arthur Bertrand (Paris: Hachette, 1882-1893). Sabatini would doubtless have run across these volumes of memoirs of the French court in his researches, and from them his drawings, if not otherwise. I’ve found copies of the swordplay image in both the British Museum and Rijksmusem.

So, there we have it! Or do we? I think almost certainly this is Sabatini’s inspiration. But does the drawing actually represent what the author described?

Almost certainly not.

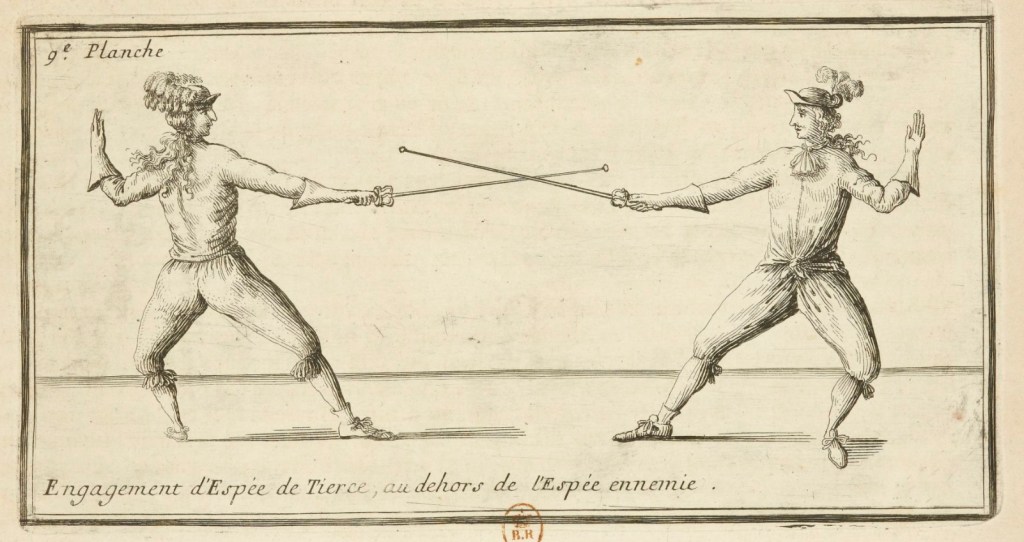

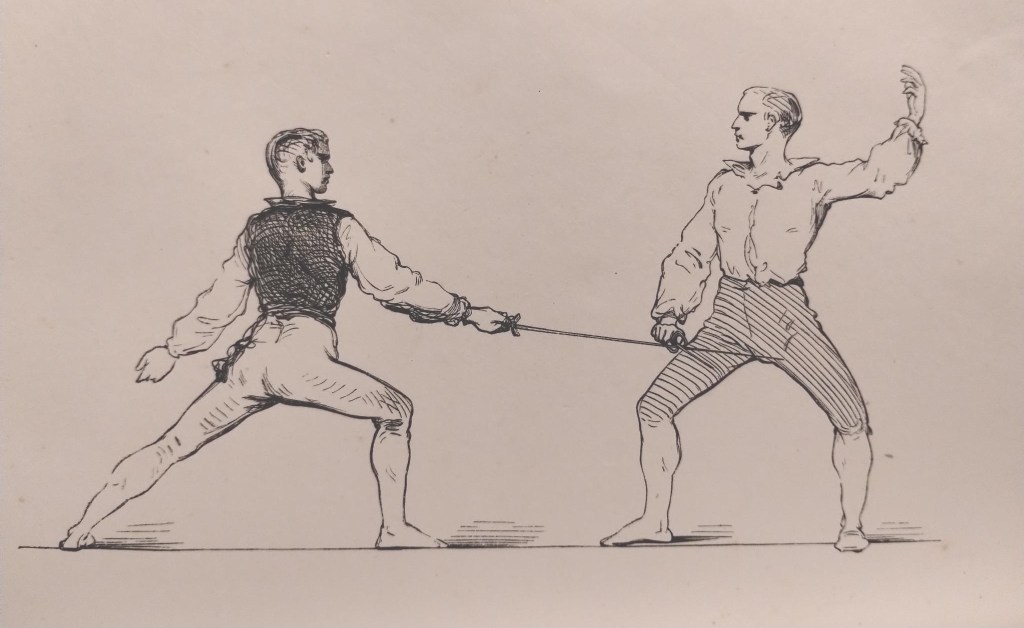

The two images below are from Les Vrays Principes de l’Espée Seule by the sieur de la Touche, 1670. The first shows the long lunge in use, or at least promoted (it requires great flexibility), at the time, although not as long as the extreme lunges above, along with the en garde. The second also shows the common French en garde of the 1660s and 1670s, with most of the weight on the rear leg and the lead leg almost straight.

Vestiges of this en garde remain in some of the French schools today. A few years ago, although Olympic gold medalist Dr. Eugene Hamori had been mentoring me as a fencing teacher for two decades, he had not given me a fencing lesson since 1981. As I came en garde very upright, almost leaning back, a position I’d picked up from years of giving fencing lessons, he immediately said, “That’s a beautiful French guard, Ben. Now lean forward a little bit, like a Hungarian.”

We find this unbalanced French en garde not only in de la Touche’s work, but in other images as well, as shown below. The guard does have the advantage of keeping the body well back and even permitting one to lean back even farther — the first commandment of swordplay is (or should be) to hit and, especially, to not get hit. But the guard has the disadvantage of limiting mobility, including a slower attack (but then, that’s not what the French school was most noted for anyway at the time).

Most French schools would soon place less extreme emphasis on this heavy rear foot position, although it would remain in use to a lesser degree for another century.

So there’s an end on it, yes? Sabatini’s inspiration and its reality?

Or is there more?

In my experience there always is. Below, from Alfieri, here’s a swordsman leaning backward, weight on his rear leg, to avoid a thrust while thrusting in turn. It doesn’t take much to imagine the addition of a small lunging movement off the line with the rear leg. In this case, though, the fencer on the right has made a single tempo movement, thrusting as he simultaneously evades an adversary who has rashly ventured too close, or has been tricked into doing so. Tom Leach provides no such opportunity. 🙂

Still, I think we have Sabatini’s original source above in the du Bouchet drawing, and therefore the “queer, un-academic” technique of Charles de Bernis as well.

However, the most useful lesson, at least fencing-wise, from the novel may be the admonition derived from the following lines:

“…and that, too confident of himself, he had neglected to preserve his speed in the only way in which a swordsman may preserve it.”

In this time of pandemic, fencers may improve their footwork, increase their flexibility and strength, study strategy and tactics, and so forth. But it takes free fencing — practice with an adversary — to maintain the most important components of fencing speed: the sense of tempo and the ability to react without hesitation. Without these, raw speed is worth next to nothing sword-in-hand.

Next up in the series: the duel on the beach in film!

Update!

I have often thought that the final technique in the duel choreographed by Fred Cavens for the Flynn-Rathbone duel in Captain Blood (1935) was his take on Sabatini’s technique as described in The Black Swan. It is mindful to remind ourselves that almost none of our ideas and inspirations, particularly in swordplay, are original, and so it is here. The 1952 photograph below, which I ran across quite by accident recently (September 2023), shows Fred Cavens lunging at actor-swordsman Cornel Wilde — who is making a lunge with the left foot exactly as described by Sabatini in The Black Swan! I would not be surprised if Cavens, as I was, was unsatisfied with his first answer. Clearly he found it — at least seven years before I was born — and as noted above, the technique does work! Below is a beautiful representation.

Technical End Note on Parrying Leach’s Low Attack: Arguably there are five parries that might possibly deflect Leach’s blade: septime, octave, seconde, quinte (low quarte), all by different names in the 1680s and some not really even in much use at all; and a largely unfamiliar vertical parry made straight down, noted by Augustin Grisier in 1847 (he names it cinquième or quarte-croisée), described in some of the old Italian schools, and also described by Alfred Hutton in his famous fencing text, Cold Steel. He describes the parry as being effective against an upward vertical cut toward the “fork” aka the groin.

Such vertical and other below the waist cuts are the reason, by the way, that the modern saber target is limited to the body from the waist up. This is due to the Italians who made the rules more than a century ago, intending by them to protect their manhood. Yet the myth of the saber target “being limited to above the waist due to the saber being a cavalry weapon, and you wouldn’t want to hurt the horse,” persists in spite of being arrant nonsense. In fact, the modern “Olympic” saber derives from the light dueling saber of the nineteenth century, and it was used in duels afoot. As for not hitting the horse or below the waist? Such blows were commonly permitted in duels among many various schools and peoples, and always in warfare.

Below the waist attacks, especially to the knee, have long been common with cutting weapons, but somewhat less so with thrusting weapons, at least when the legs are target (the area below the ribs is in fact an excellent target with real thrusting weapons), due to the fact that a thrust to the legs is rarely incapacitating, unlike a cut, and leaves the attacker’s head and torso wide open for a possibly fatal counter thrust. Thrusts to the groin, besides generally being considered dishonorable when intentional, may easily miss and slip between the legs, leaving the attacker open as just noted. In my experience, fencers hit in the groin by thrusting weapons are usually themselves at fault, having parried late or insufficiently, or used a filo/grazing or yielding parry incorrectly and thereby carrying the attacking blade to the groin.

The vertical downward hard parry of Grisier et al is used unknowingly by some epee fencers today, and if asked would probably define it as an incomplete seconde. I use it and find it highly effective against hard-driven low attacks, particularly when made Hungarian style with beat as the opposition parry is made (Sir Wm. Hope also recommended that parries be made in this manner). Grisier recommends riposting in opposition. The parry is made by lowering the hand while simultaneously bringing the point perpendicular to the fencing line — pointing inside, that is, 90 degrees away from the fencing line and definitely not in line with the adversary, contrary to most advice of keeping the point in line with the target. It is in spite of this a highly effective parry and riposte. One imagines de Bernis using it successfully and riposting with an opposition thrust to the eye, given that much of the target would be protected by Leach’s long lunge and extended arm.

In order for any of the first four of these parries to be effective against a low thrust, the parrying hand must be lowered significantly in order to bring forte to foible, making for a slow parry. If the parry is begun after the attack has developed, instead of at its initiation, often by anticipating it, it will likely prove ineffective.

Note again that Sabatini writes that no direct parry — one made in a more or less straight horizonal line — can stop the attack. Sabatini probably intends to mean that no simple parry (direct, diagonal, half-circle), rather than a circular parry would stop the attack, for a circular parry would likely be too slow and would be forced by the attack. A true direct parry against the attack would have to be made from an en garde held in a very low line, McBane’s “Portuguese guard” for example. But if de Bernis had been in this guard, Leach would not have made his low attack.

However the direct vertical parry just described, if correctly timed and made with a powerful beat with the middle of the blade on the attacker’s foible or middle, can be highly effective against such attacks, capable of being forced only with great difficulty. Even so, Sabatini is largely correct when he writes that such a low powerful attack is not easily parried, at least not conventionally.

Hutton notes that septime is also effective against low vertical upward cuts. In my experience it has some utility against low thrusts, particularly if the parry is made with a combined beat/opposition and the hand is dropped to bring forte against foible. However, it is often easily forced.

* The pirate ship Black Swan may be the ultimate inspiration for the concept of Disney’s Black Pearl (rather than the Wicked Wench). Details here…

Copyright Benerson Little, 2020 – 2025. First published 10 September 2020. Last updated 15 January 2025.

The Duel on the Beach, Part I: In Fiction & Illustration

It’s all too easy to imagine a duel on the beach between pirates or, as fiction and film often have it, between pirate captains. A sandy beach, palm trees, spectators often including both pirates and a woman in distress, a tropical sea and sky–a duel is mandatory in the genre if only because the setting demands one.

This blog post is part one of a likely five part series on the classical piratical duel on the beach, a pirate trope too evocative to pass up and one based to some degree in reality too. Only the trope of the tavern sword brawl is as prevalent, but not as romantic.

Up first is a look at the sandy duel in fiction. Part two examines the duel described by Rafael Sabatini in The Black Swan, in particular the origin of the hero’s singular technique. Part three reviews the duel on the beach in film, part four takes a close look at the most famous fictional duel on the beach, that depicted in Captain Blood (1935) starring Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone, and part five discusses the historical reality of the duel on the beach.

In particular, we’ll look not just at some classic swashbuckling episodes, but also consider how genres and tropes are created, and how misinterpretation often not only leads us astray, but also, at times, to authentic historical discoveries.

It’s entirely likely that I’ll also throw in a blog post each on the inquartata, the flanconnade, and also the intagliata and similar techniques of “lunging off the line,” given their prevalence in swashbuckling fiction and film (not to mention their utility in historical and modern fencing). I’ve already written one for the same reason on The Night Thrust; or, More Politely, the Passata Soto, and I’ve discussed Sabatini’s hero’s off the line technique in The Black Swan, linked above. I’ll likely also write a brief post on Dutch knife fighting for reasons noted just below.

The series is also part of an effort to encourage outdoor fencing, especially at the beach or seaside. (Don’t worry, any light rust is easily removed from blades! In fact, two or three hours in a sea breeze will start to rust carbon steel.) Not too long ago the FIE (the international fencing body) in its infinite [lack of] wisdom did away with outdoor tournaments in epee, at least as sanctioned events, and national bodies followed suit. Not even the Covid-19 pandemic inspired the dour, sports-rabid international and national bodies to reconsider outdoor fencing. Tournaments held outdoors — at the beach, at historical sites, in parks — are a lot of fun for their own sake, although arguably fencing these days seems more focused on its falsely purported utility as an add-on to college applications than on fun. Some of my fondest fencing memories are of outdoor swordplay, both competitive and recreational, and their associated celebrations.

So where to begin? It seems almost too easy. At least half the blame lays with the highly enjoyable illustrator and writer of out-sized piratical myth, misconception, and trope (and even some fact!), Howard Pyle, several of whose students–N. C. Wyeth and Frank E. Schoonover in particular–followed closely in his swashbuckling-illustrator footsteps.

However, before we get to Pyle in detail, we need to note the existence of an old ballad called “Dixey Bull” or “The Slaying of Dixey Bull” which describes a duel on tiny Beaver Island (near modern Pemaquid Beach, Maine) between a pirate captain and a local fisherman. The ballad was first published in 1907 from oral tradition dating possibly as early as circa 1725 based on its mention of the “skull and cross bones,” language used, and its description of swordplay consistent with early to mid-18th century prizefighting and broadsword technique. The song was sung in Maine and environs, was apparently well-known by seamen and fishermen, and their wives and daughters, and it’s entirely possible that Howard Pyle was aware of its existence.

Dixie Bull was the first-noted pirate of New England and the northeast coast of North America. In 1632 some Frenchmen in a pinnace robbed him of his trading stock of blankets, “ruggs,” coats, &c, for which he sought reprisal at sea in his own small craft. Failing to make good against the French he plundered some local Englishmen, thereby turning pirate. In 1633 three deserters from his crew said he’d gone over to the French, although he is believed to have eventually returned to England.

In the ballad, which has no known basis in reality, as is the case with many ballads of the era, Dixey Bull is challenged by local fisherman Daniel Curtis to a duel with broadswords. If Bull wins, he and his crew keep their stolen treasure. If he loses, the pirate crew returns the plunder and sails away. Wounded, but with a trick worthy of one of Rafael Sabatini’s heroes or the best of those of swashbuckling Hollywood, Curtis kills Bull. Of course, no such duel ever took place: pirates would never offer up their plunder on a point of honor. Whether or not the ballad influenced Howard Pyle is unknown but certainly possible.

Although Howard Pyle painted several sword duels, two of them by the seaside, it’s his “Which Shall Be Captain?” (shown above the Dixie Bull images) that may be the significant culprit, and it shows no obvious connection to the duel between Bull and Curtis. In the painting, two pirate captains struggle against each other with daggers to determine who will command. The notion of dueling for command is false, however, to be discussed in more detail in part five (or if you can’t wait, you can read about it in The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths). Put simply, captains and quartermasters were democratically elected. Even lesser officers required the approval of the crew. Dueling was never considered or acted upon as a means to gain command.

Likewise false, or at least uncommon as far as we know, is the use of daggers in duels on the beach. In fact, among buccaneers the musket was usual dueling weapon although some fought with cutlasses. However, there may be a possible exception among Dutch and Flemish seamen, who like many of their adventurous compatriots ashore had a habit of knife fighting, often using their hats in the unarmed hand for parrying. The style of fighting appears to have been more cut than thrust, notwithstanding the Dutch term “snickersnee,” which means to stick or stab and thrust, which Lewis Carroll turned into the snicker-snak of the vorpal sword. (See Buccaneer Cutlasses: What We Know for more information on cutlasses, including a bit on dueling.)

Even so, the only authenticated duel between buccaneer captains was between two Dutchmen–and they used cutlasses. Again, more on this in part five.

A duel on the beach between Dutch pirate captains is likely not what Pyle intended though, unless they were Dutch buccaneer captains of which there were in fact a fair number, more of them in service among French flibustiers than among English buccaneers. Their names are legend: Laurens de Graff, Nicolas Van Horn, Michiel Andrieszoon aka Michel Andresson, Jan Willems aka Yanky, Jacob Evertson, and Jan Erasmus Reyning among many others.

No matter his original intention, Pyle’s scene-setting has been imitated as homage, sometimes even copied, in numerous films as well as in illustrations for swashbuckling tales.

However, Pyle’s painting can only ultimately be said to have inspired the trope to far greater prominence, for a decade earlier, in 1899, Mary Johnston’s To Have and to Hold was published, a romantic novel of ladies, gentlemen, settlers (or invaders), Native Americans, and pirates. Notably, Howard Pyle painted the frontispiece, and, more on this later, Johnston’s works were a significant influence on Rafael Sabatini, author of Captain Blood and many other great romantic, often swashbuckling, novels.

Pyle’s painting of the duel for command, between gentleman hero and the last of three pirate villains he fights one after the other, takes place on what is known today as Fisherman’s Island off Cape Charles, Virginia. All three duels are described not in terms of fencing technique but via the hero’s thoughts and emotions as he fights–and easy way to avoid describing actual swordplay. Side note: the hero’s second adversary is a Spaniard (the best blade in Lima) and the third is the “man in black and silver”–almost as if the duel takes place in The Princess Bride. I won’t add the duel in The Princess Bride to this post, although I’m sorely tempted, as it takes place not on the shore but on the cliffs high above.

The entire composition of Pyle’s painting has been copied by many illustrators and filmmakers, including Douglas Fairbanks in The Black Pirate (1926) and Michael Curtiz in Captain Blood (1935).

As for the action itself, duels in fiction and film require high drama. It helps if the hero and his adversary are equally matched, although often the hero ends up hard-pressed but prevails in the end, often by stratagem. Occasionally we see the hero who is always in control, whose swordplay is so exceptional that the villain comes soon to realize he (villainous duelists are almost always a he, thus the pronoun) is entirely outmatched. Here the drama derives from the villain realizing he’s going to lose and be rewarded as he so richly deserves.

Depicting swordplay in fiction can be difficult, or rather, is actually quite difficult. Explain too much and you lose drama and tempo. Explain too little, and the duel is reduced to vague nonsense, even if dramatic. Using a few modern fencing terms has been the refuge of many novelists–but modern terms lack the flavor, and often the correct historical technique, to adequately depict a historical duel. And even in this case only fencers will actually understand what’s going on. In other words, to understand fencing you must be a fencer (and this is part of the reason, in spite of the FIE’s attempts at dumbing down fencing, why it will never be, and frankly should not be, a great spectator sport). But writers often cheat and describe swordfights only in vague terms or through the protagonist’s mental state.

In related fashion, writers often forget, or far more likely haven’t learned, that fencing on a shoreline causes changes in footwork and agility. Fencing in sand tends to slow the action down a bit, footwork in particular. Lunges are slower because the foot slips even in the best-compacted damp sand. Of course, if the beach is rocky, as in Captain Blood (1935), or covered in various beach and dune plants, this may help prevent the foot from slipping although it may also increase the risk of tripping and falling. Fencing in shallow water can diminish the lunge or even negate it.

Further, sand gets in the shoe, which can affect footwork. Sand is also readily available for villainously throwing in the adversary’s eyes. And, as in the case of all outdoor fencing on uneven ground, there’s always the chance at taking a special form of tempo, that of the brief surprise when the adversary accidentally steps in a hole or runs into a bush or trips over driftwood, or is maneuvered into doing this. Distraction, however brief, can be fatal.

There are partial remedy for these hazards, which I’ll discuss in part five, and, like running in the sand, you’ll at least in part naturally adapt to the best technique over time. (Thanks Bear Mac Mahon for your brief comments and reminders on fencing in the sand. 🙂 )

Sadly, seldom does any of this make it into fictional accounts of duels on the beach. But no matter! It’s the ring and spark of steel on steel while the sun glints off sand and sea we’re after. Which, by the way, is another issue with fencing on the beach: glare, which can easily be used to advantage by maneuvering the adversary into position with his face facing sun and sea, or even a sandy sea breeze…

On occasion there artwork of a duel on the beach unassociated with a published story, and even when discovered there is often something of a written description associated with it, as with Frank Dadd’s “The End of the Game” published in The Illustrated London News:

The duel on the beach also makes its way into pirate pulp fiction, as in these novels by Donald Barr Chidsey (the rhythm of whose name makes me think of Simon Bar Sinister):

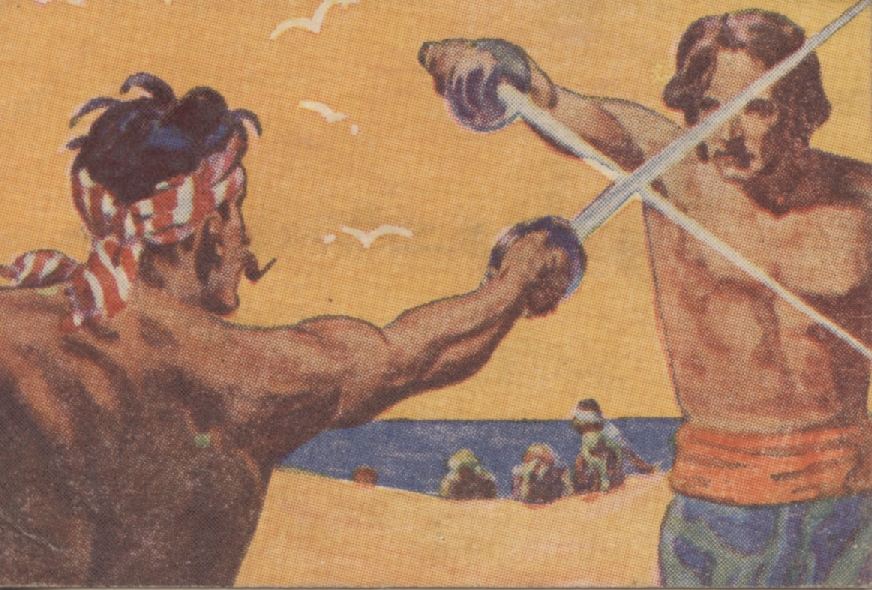

The duel on the beach has had a fair amount of depiction in other print media as well, including comic books and trading cards:

The front cover of Buccaneers (January 1950, #19) showing a duel on the beach, with costumes and en gardes inspired by a combination of several films. Notably, the duelist on the left has an en garde typical of many beginning fencers.

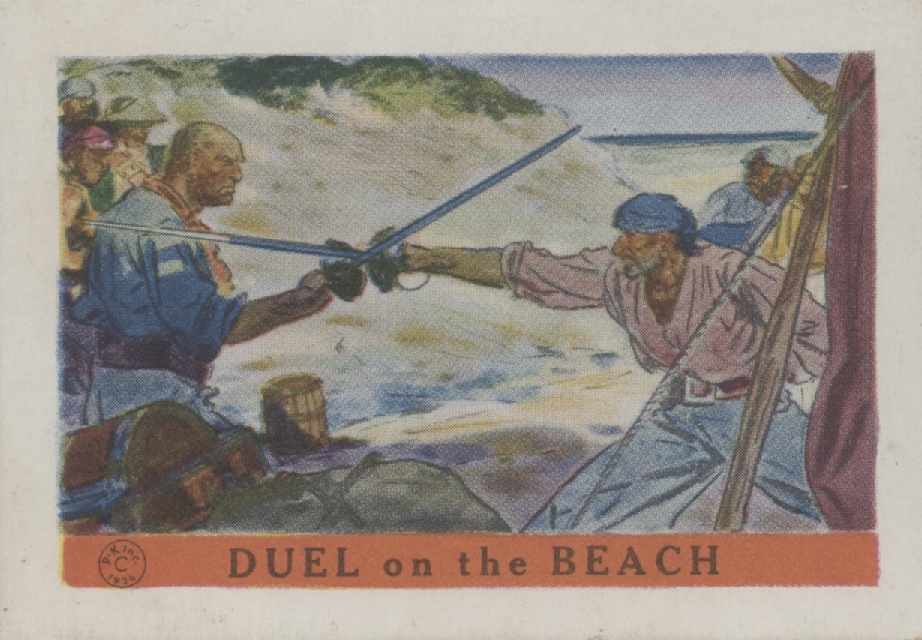

A trading card duel, with buccaneers watching as in Howard Pyle’s paintings and in the films The Black Pirate and Captain Blood.

A duel over buried treasure below, with daggers, clearly inspired by the famous Howard Pyle painting.

Below, a duel for command–a myth, as is the duel or affray over buried treasure.

The trading card above probably owes as much to Douglas Fairbanks’s The Black Pirate (1926) as it does to Howard Pyle and various fiction, as shown below–but then, The Black Pirate owes much to Howard Pyle, purposely so according to the film program. We’ll discuss the duel in this film in more detail in part three.

There is a duel on the beach–well, not the beach but on higher ground on tiny Beaver Island, for the “ledges” (rocks) ran down to the water–in Clothes Make the Pirate by Holman Day (1925), a comic pirate novel. The duel is based on the fictional encounter between Dixie Bull and Daniel Curtis but is fought here between two tailors, Tidd and Sneck, both of them impersonating pirates (the former pretends to be Dixie Bull), and the two tailors merely pretend to fight, working out the details while briefly hidden behind some spruce trees during the engagement.

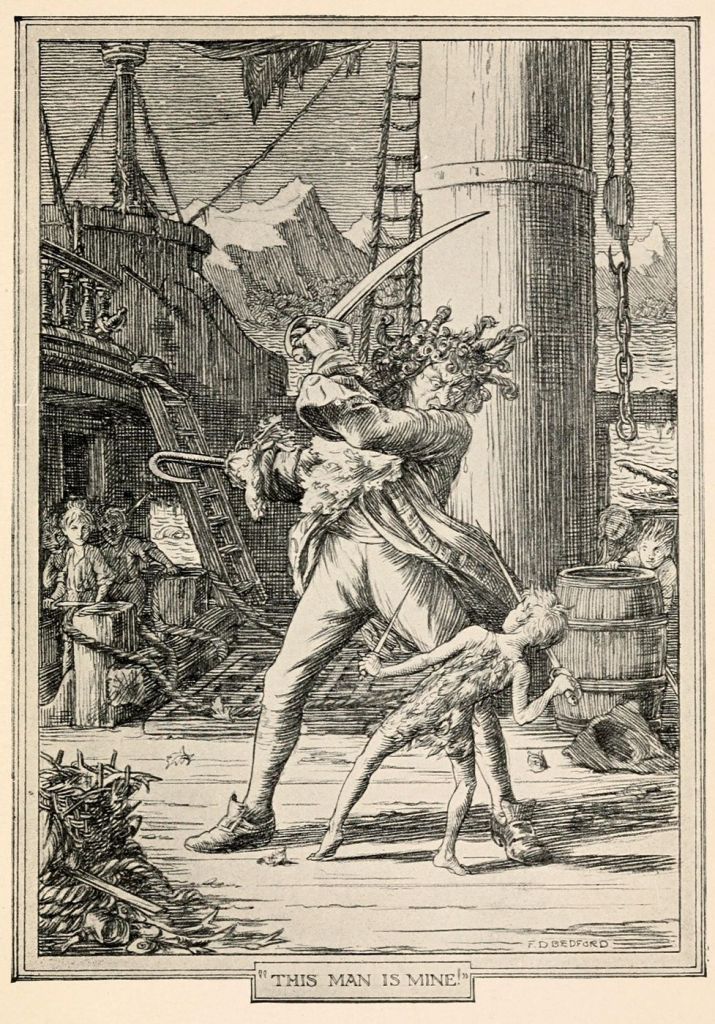

Of course, one of the great duels on the beach is depicted in Captain Blood: His Odyssey (1922) by Rafael Sabatini, in particular the dramatic build-up and famous dialogue. But alas, the duel itself is described in only two lines:

“It was soon over. The brute strength, upon which Levasseur so confidently counted, could avail nothing against the Irishman’s practised skill.”

In part four we’ll look further into this most famous of duels as it was depicted in the 1935 film starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone.

Numerous illustrators have tried their hand at the duel, some more successfully than others, historical accuracy (and even fictional accuracy) often to be desired.

This is a good opportunity to segue to several tobacco card illustrations of duels on the beach. Up first is Captain Blood, although based entirely on the duel in the 1935 film.

Although I can’t discover any connection to specific works of fiction per se, four of Don Maitz’s paintings of swordplay on the beach evoke classic swashbucklers and the paintings of Howard Pyle and N. C. Wyeth. Mr. Maitz is a famous illustrator, perhaps most noted for his depictions of Captain Morgan for the rum of the same name. Copies of his works can be purchased here.

The purportedly authentic duel between Mary Read and a fellow pirate who was threatening her lover (or at least Charles Johnson so claimed, but he lied often in his 1724-1726 chronicle of pirates) shows up in an Allen & Ginter Cigarettes trading card, circa 1888. I’ve included it here as the account may well be fictional.

Norman Price illustrated this duel in The Rogue’s Moon by Robert W. Chambers (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1929), yet another prolific (roughly one hundred novels, short story collections, and children’s books) popular genre writer already forgotten less than a century later. The story is enjoyable enough even given its light genre and Chambers’s style. It is action-filled and interspersed with scenes of mild titillation, and includes several major characters of the era (Blackbeard among them) in prime appearances, with pirates as the story’s villains. The protagonist is a cross-dressing, seeking-revenge-against-pirates, older teenager named Nancy Topsfield. The novel pretends to a background of historical accuracy, which is in fact, as with most of the genre, only superficial at best.

The duel is brief but exciting, and follows the manner described by Charles Johnson as in use by the early eighteenth century pirates of the black flag: pistols followed by cutlasses. Read’s sword is a “Barbary” or “Arab” blade, which might be a nimcha (of which were some naval captains who owned these swords, usually as trophies) but which the illustrations suggest is more likely a scimitar (or shamshir if you want to be pedantic–but scimitar was the common word in use by Europeans at the time). In either case her blade looks curved enough that she needs to hook her thrust. The duel ends with a near-decapitation.

Although Price’s drawings and paintings of men in the story are reasonably historically accurate by the low standard of popular illustration, he takes pop culture liberties with the leading female characters. He and Chambers dress Mary Read as a typical 1920s/1930s Hollywood starlet-type of pirate, sometimes termed “pirate flapper” and derived most likely from Douglas Fairbanks’s style of dress in his 1926 The Black Pirate. Female pirates were commonly depicted in this fashion during this era, ranging from magazine ads for sterling flatware to Hollywood studio portraits.

Given the rarity of known pirate duels, it’s not surprising that so few are depicted in various literature. However, at least one is. The famous duel, familiar if you’ve read the French edition of Alexandre Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America, or other related French texts (or even some of my books), between Laurens de Graff and Nicolas Van Horn at Isla Sacrificios near Veracruz in 1683 is also depicted on a cigarette card. However, given that this duel actually occurred and we have period accounts of it, we’ll save further description for part five. Whoever illustrated the duel below had not read the rare eyewitness account (unsurprising at it is neither easily found nor easily deciphered) although he or she may have read a secondary account, possibly Exquemelin’s.

All of this rather meandering exposition of the duel on the beach in fiction is leading us to a single novel that epitomizes it above all others: The Black Swan by Rafael Sabatini. And, given its role and singular technique, I’ll devote part two of this series to it entirely.

An honorable mention of sorts must go to George MacDonald Fraser’s comic novel The Pyrates (Collins 1983 & Knopf 1984). It’s one of my favorite pirate novels. It’s a campy, loving, satirical send up of pirate fiction and film, including Captain Blood: Fraser was a fan of Sabatini as I was and remain (and as well of Fraser). My attachment is also due in part due to the fact that when I first read it I was a somewhat cocky young naval officer, Navy SEAL, and swordsman recovering on a San Diego beach from an injury received on a Hawaiian beach during deployment.

Fraser’s duel on the beach scene is not traditional. Instead, it is a blindfolded duel between the super Sabatini-esque hero, Benjamin Avery, and the anti-hero Colonel Thomas Blood, a character based on the real quasi-gentleman who stole the English Crown jewels and whose name Sabatini appropriated for his honorable hero. Soon abandoned by the pirates who set them en garde on Dead Man’s Chest (an islet or cay in the Virgin Islands and the inspiration via author Charles Kingsley for said lyric in Treasure Island), the two adversaries fence comically in hoods, with swords tied to their hands and a small bell as well to cue them.

A line or two captures the spirit: “Even Black Sheba, concerned as she was for Avery, could not repress a smile as he came academically on guard, extended himself in a perfect lunge, and fell slap into the surf.”

I’d have to do a more detailed survey of recent fiction to adequately note any other significant renderings in fiction of duels on the beach. At the moment, only one comes to mind, that depicted by famous Spanish novelist Arturo Pérez-Reverte in El Puente de Los Asesinos (2011), part of his excellent Capitán Alatriste series. Alas, there is no English translation. The first six were translated, but not the seventh due to low sales, an indication of where the genre–especially “upmarket” swashbucklers–is today, replaced largely, and sadly, by fantasy.

Much if not most of the swashbuckling fiction that does make it print today tends to fall into the “writing by trope” category with inaccurate historical detail (a problem with much historical fiction in general today, to the point that many authors have accepted fictional tropes as historical fact and will vigorously, even hilariously, defend them) and “dialogue as might be spoken by modern suburbanites at a cocktail party” (likewise a common problem as a journalist friend pointed out), or is sadly relegated to small ebook and print-on-demand presses with little if any access to brick-and-mortar chains and independents. I remain hopeful that this will change. And if I bother to dust off Fortune’s Favorite, the sequel to Fortune’s Whelp, I’ll let you know–it has a duel on the beach in it. In the Caribbean. Naturally. 🙂

On a more positive note, I’ll close with two watercolors of pirate dueling on the beach, by one of the most famous American painters of all: Andrew Wyeth, son of illustrator N. C. Wyeth, around the age of twenty.

And last, well, just because it’s a beautiful beach painting in the pirate genre by Andrew Wyeth…

NOTES

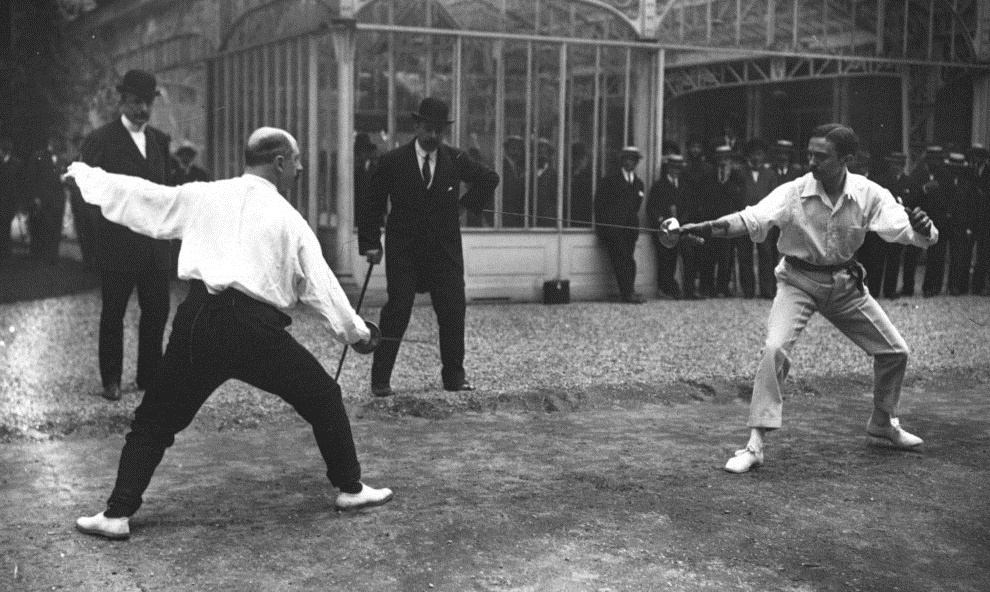

A couple of notes on the duel at Teviot beach by Howard Pyle: Aficionados of fencing history will note that Pyle clearly took his inspiration from late 19th and early 20th century epee duels, many of which were photographed, and some even filmed. In the late 17th century it would be unusual for there to be a directeur de combat (someone who monitors the fight, in other words, and ensures that no villainy is perpetrated). Further, seconds often fought too, and spectators were absent more often than not.

Even more critically, both swordsmen are in sixte rather than tierce (although one might argue that the fencer on the left is actually correctly in carte, perhaps having just been parried to the outside line by a circular parry). Sixte, not yet called by this name, was not unknown but was disregarded by most masters and fencers in spite of its utility in closing the “light” (hole, open target) revealed in tierce. Sixte is a weaker position and requires more blade set and wrist angulation (some of the latter was later relieved by modifying the way the grip was held) than tierce, which is a stronger position physically and whose point falls naturally toward the adversary’s shoulder. The guards shown in the painting are more typical of fencers in Pyle’s day (and in ours as well).

POSTSCRIPT for members of the Huntsville Fencing Club: post-pandemic we’ll [finally] host a rum tournament on the beach. 🙂

Copyright Benerson Little 2020. First published September 1, 2020. Last updated October 8, 2024.

The Women in Red: The Evolution of a Pirate Trope

With news that Disney is planning a new standalone pirate film starring a female pirate, it’s time review what has become a pirate trope: the woman in red, specifically, or at least often, a redhead. Why this trope in regard to a new Disney film? Because speculation has it that the film will be tied to Redd the Pirate above.

UPDATE: According to Margot Robbie in the press on November 14, 2022, Disney has killed the project, although rumors periodically surface that Disney continues to look at continuing the franchise, including a film with a female protagonist. A pity indeed that the rumored Robbie film was cancelled, it might’ve been quite the film. Certainly the genre needs a new female-led pirate film hearkening back to the Golden Age of Piracy and Pirate Film. There have been only a few made. Shout-out to The Pirates (2014), a Korean comedy-drama about Korean pirates, with strong overtones of the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, starring Son Ye-jin. (And please let it not be about Anne Bonny! See below…)

In the meantime while waiting for a new pirate film with a female lead, we’ll take a quick look at some of the myths and realities of female pirates during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy in the Americas from roughly 1655 to 1730.

The obvious apparent origin of the woman in red (a “scarlet woman”?), at least in terms of pirate fiction and film, is the Redhead in line in the bride auction–“Take a Wench for a Bride”–in the original version of the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean attraction in which drunken pirates shouted, “We wants the redhead!” Forced marriage, in other words, and all of its associated crimes.

Notably, text on the back of the publicity still describes the scene as an auction: “Gold-hungry pirate captain puts the town’s fair maidens–and the ones not so fair–on the auction block for his rowdy crewmen.” Thankfully, things have somewhat changed since then, tongue-in-cheek humor or not.

The Disney auction scene was doubtless inspired by scenes in The Black Swan (1942), Anne of the Indies (1951), and, in particular, Against All Flags (1952), in which captured women are portrayed as captives to be sold or given away as plunder. Both Anne of the Indies and Against All Flags have auction scenes of female captives, and the latter has an auctioneer with whip-in-hand as in the Disney attraction.

When it first opened in 1967, the Disney attraction was intended as–and in fact was–a tongue-in-cheek, lighthearted, swashbuckling film-based version of buccaneers sacking a hapless Spanish town in the Caribbean. Marketing text associated with early publicity stills noted that the ride was a “thoroughly realistic re-creation of buccaneer days.”

To enjoy the ride–which I did and still do–requires viewing it as a fantasy rather than a depiction of reality, for the reality of buccaneer attacks in the seventeenth century was anything but romantic to the victims: torture, rape, murder, and the enslavement of free men, women, and children were common. Documentary evidence of what today would likely be defined as resulting PTSD, among both victim and perpetrator, exists.

Like most of our fictional and cinematic adventure, we tend to sanitize or ignore facts in order to help create a fantasy more amenable to entertainment. Humans have done this for millennia. And there’s often nothing wrong with this unless we confuse the fantasy with the reality, which unfortunately happens all too often.

Today, the ride has been modified somewhat to both fit with the Disney pirate films, which are only loosely inspired by the attraction, and to bring the attraction up-to-date with current social mores. The latter changes have generally been a good thing, I think, even if the changes are not historical (and a few I disagree with). The attraction is a swashbuckling fantasy, after all, not an accurate “Audio-Animatronic” documentary. I’m much less enamored of the changes in keeping with the film franchise.

The most significant of the changing mores alterations to the attraction was the conversion of the pirates-chasing-women scene into one of pirates-chasing-food, and the conversion in 2018 of the bride auction scene into one of conquered residents bearing possessions, perhaps as ransom, and of the famous red-dressed redhead showing a leg into a red-dressed redheaded female pirate standing guard (and still, after a fashion, showing a leg).

Personally, I prefer the new scene and new redhead, ancient passing pre-adolescent fantasies notwithstanding.

In general, as in the original trope-setting (and great fun to watch) pirate swashbuckler, The Black Pirate (1926), leading women in pirate films are usually depicted as the “tavern wench” or “exotic wench,” or other saucy secondary love interest; or the “swooning heroine;” or the “pirate woman.”

The “pirate woman” is usually by far the most interesting, although too often she, Hollywood-style, gives up piracy at the end of the film in exchange for true love. Or she dies in battle, her true love unrequited, her true love interest running off with the “good girl”–often the swooning heroine. At least Against All Flags with Maureen O’Hara and Cutthroat Island with Geena Davis avoided this trope.

Sometimes the tropes are combined: Elizabeth Swann in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl goes from a nod at the literally swooning–via an over-tightened corset (“stays” to be correct)–heroine to pirate woman.

She also wears a red dress in the first film of the series, in scenes which combine multiple tropes: woman in peril, woman tied-up, woman with (airbrushed via CGI, reportedly) cleavage. The dress is a likely homage to the Disney attraction. A red dress also shows up on Scarlett, a tavern wench aka prostitute.

The red dress shows up in other pirate films as well, and as apparent copies or homages in Halloween costumes and video games.

Geena Davis stars in Cutthroat Island (1995, Carolco), and in one scene swashbuckles her way tolerably well with an anachronistic rapier and dressed in a red dress borrowed from a prostitute. The dress is clearly a nod, perhaps more than a bit humorous, at the Disney ride. In fact, Cutthroat Island often seems like one long string of pirate tropes, homages, and stolen scenes. Great soundtrack, though, and Davis does well as a pirate captain.

Now is a good time to briefly point out the reality of women pirates during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy 1655 to 1730. Strictly speaking, we know of only two who can be truly said to be pirates of the Caribbean: Anne Bonny and Mary Read, the former of whom gets all the cinematic glory while the latter, if what Charles Johnson wrote about her is true even in part, was the real swashbuckling bad-ass of the twain.

If Johnson’s early eighteenth century account is true, Read had been thrice a soldier in disguise, then a pirate, and even a privateer, in disguise, and reportedly fought at least one duel against a male crew member. Of course, this may be entirely an invention of the author, and his account of Read’s army service may have been inspired by the real life of female soldier-in-disguise Christian Davies. Although a fictionalized account of her life was not published until 1739, her story was known at the time Johnson’s pirate book was written.

Whether a true tale or not, it’s not Read’s warrior-woman story that ends up in fiction and film, but that of redheaded Anne Bonny–or at least she’s assumed to be redheaded because she was Irish and reportedly had a hot temper. Bonny gets all the glory, even though she may have been merely the girlfriend along for a joyride with her bad boy pirate boyfriend. Or not. Likewise Mary Read. We simply don’t know enough about her or Mary Read. Johnson may have invented the past histories of both to “sex up” his book for sales potential.

Of course, it’s entirely possible that both were as bold as Charles Johnson described them, even if they only dressed as pirates when attacking at least one vessel, and remained in women’s clothing otherwise. And their piracy was pitiful, nothing more than cruising in a tiny 12-ton sloop, not the 40-ton sloop Johnson described, and robbing a few “mom and pop” local trading vessels, including a canoe paddled by an old woman — hardly the stuff of Hollywood. Of course Johnson had to exaggerate for the sake of book sales!

Bonny, though gets all the attention, thanks largely to her relationship with “Calico” Jack Rackham. Writers are often lazy, and it’s easier to combine Read’s martial prowess with Bonny’s reported temperament and relationship with Rackham. However, not all writers who fictionalize the female pirate pair are as lazy. Some, including Erica Jong, have balanced their accounts of the two women.

But it’s Read, in my opinion, who deserves a movie.

Perhaps Anne Bonny, the assumed redhead, has also given us the redheaded part of the redhead in the red dress trope.

There are no other known women pirates of the Golden Age but for two who were technically pirates under the law, each having participated in utterly inept attempts at petty piracy, one of them comically so. Notably, two of the most commonly cited women pirates of the era were not pirates at all (please please please ignore Wikipedia!): Jacquotte de la Haye is entirely fictional, a creation entirely of author Leon Treich (Les Gentilshomes de la Flibuste, 1944, a factual-fictional account of buccaneers and some pirates written for a juvenile audience), and Anne Dieu-le-Veult, a wealthy widow, married the famous Laurens de Graff after his buccaneering days. She was never a member of his crew, nor is there any evidence that she was a member of any other crews. Treich is also responsible for exaggerating myths about Dieu-le-veult to an even greater degree, and even imaging deeds that never happened (including the utter nonsense that de Graff died in battle at her side).

More detail on Rackham, Bonny, and Read can be found here.