Home » Uncategorized (Page 5)

Category Archives: Uncategorized

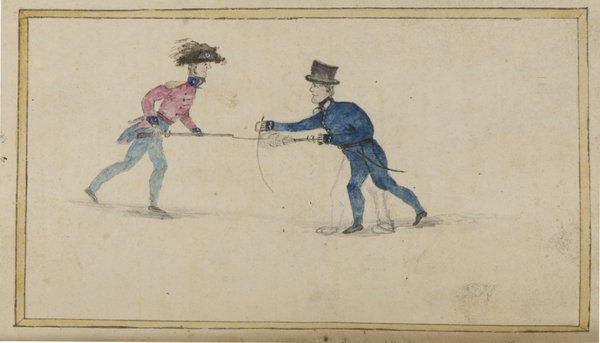

The Night Thrust; or, More Politely, the Passata Soto

“This subterfuge is termed a Night-Thrust; being a short method of deciding a skirmish in the dark.”

–Andrew Lonergan, The Fencer’s Guide, 1777.

But Edward was no longer there, or at least not where Lynch expected. Completely covered by the inky darkness, Edward had lunged backward, his left hand dropping to the ground, his body bending inward, his blade shooting forward at Lynch’s belly: the Italians called this passata soto, but some of Edward’s English contemporaries called it the “night thrust” for its utility in the darkness.

Benerson Little, Fortune’s Whelp, 2015

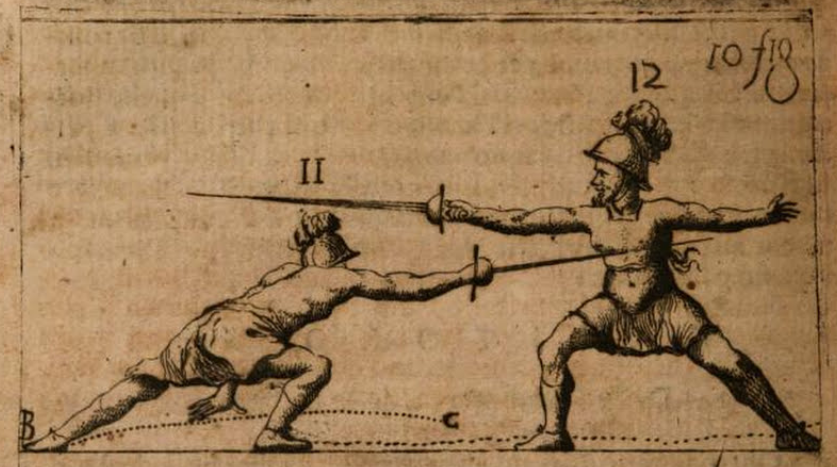

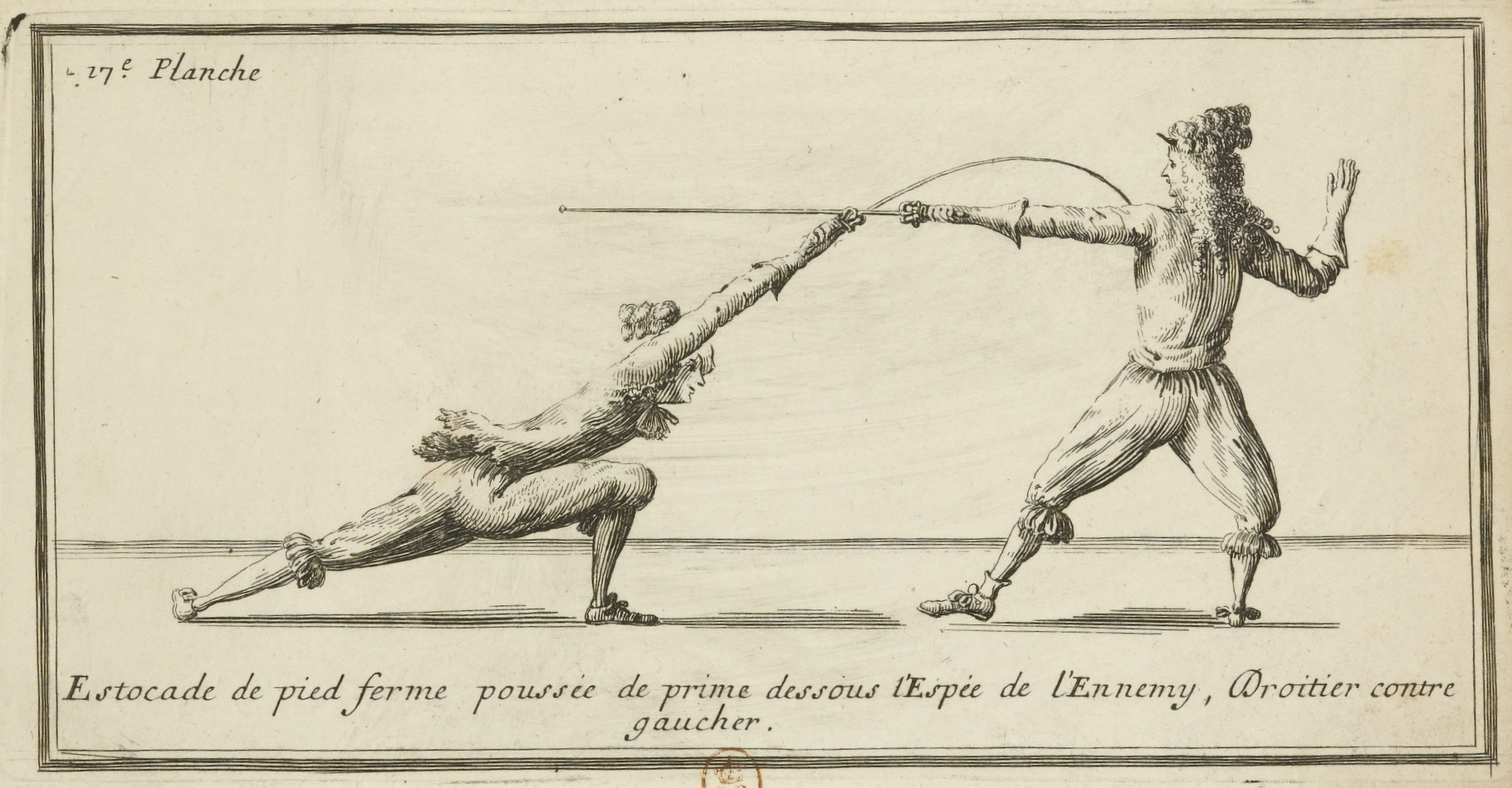

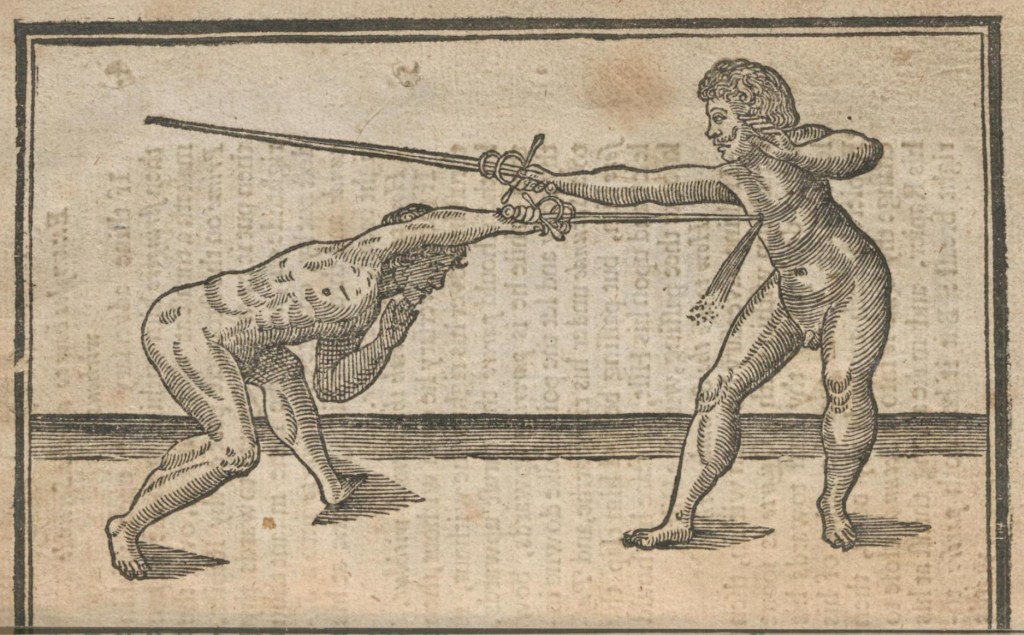

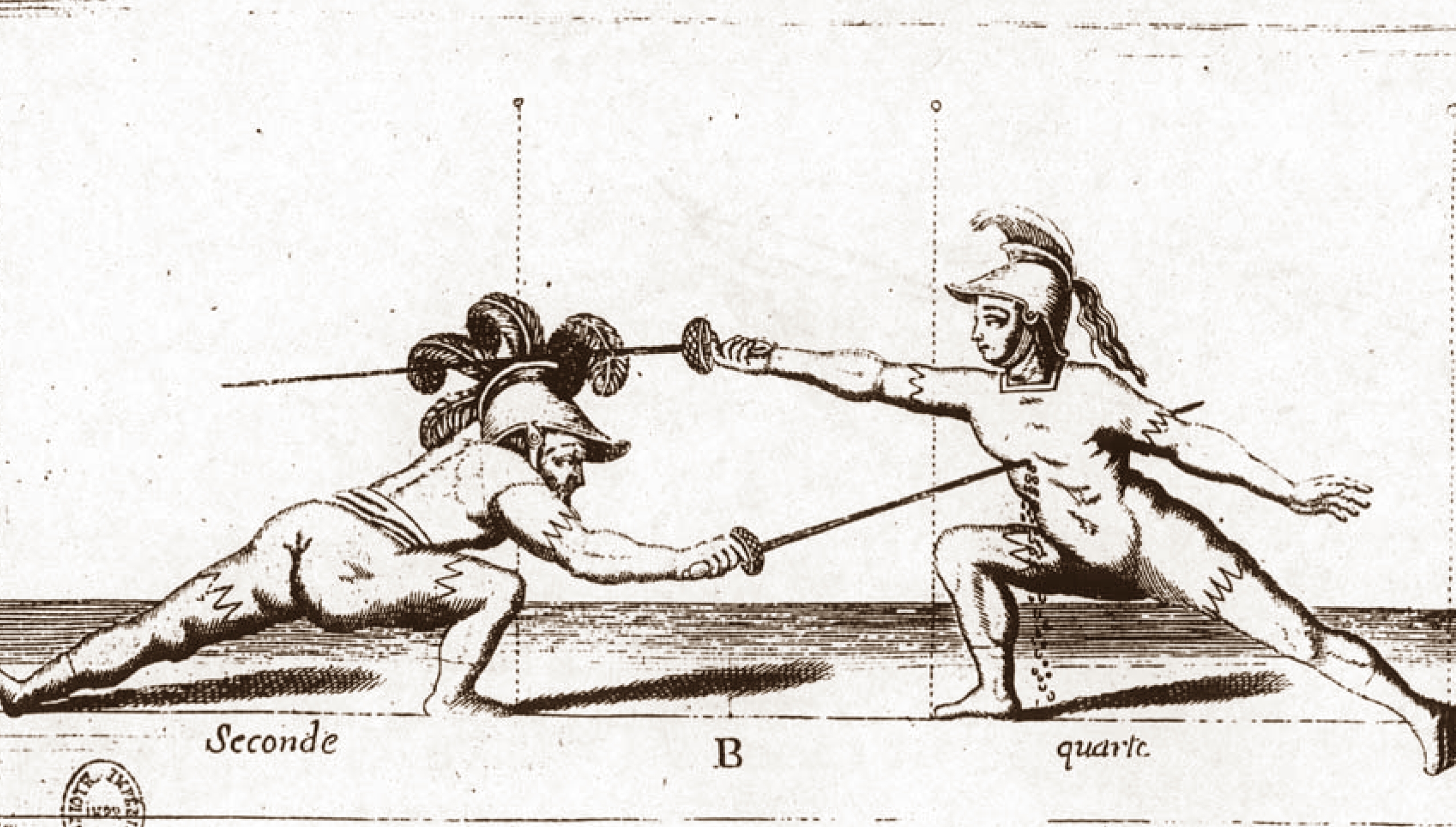

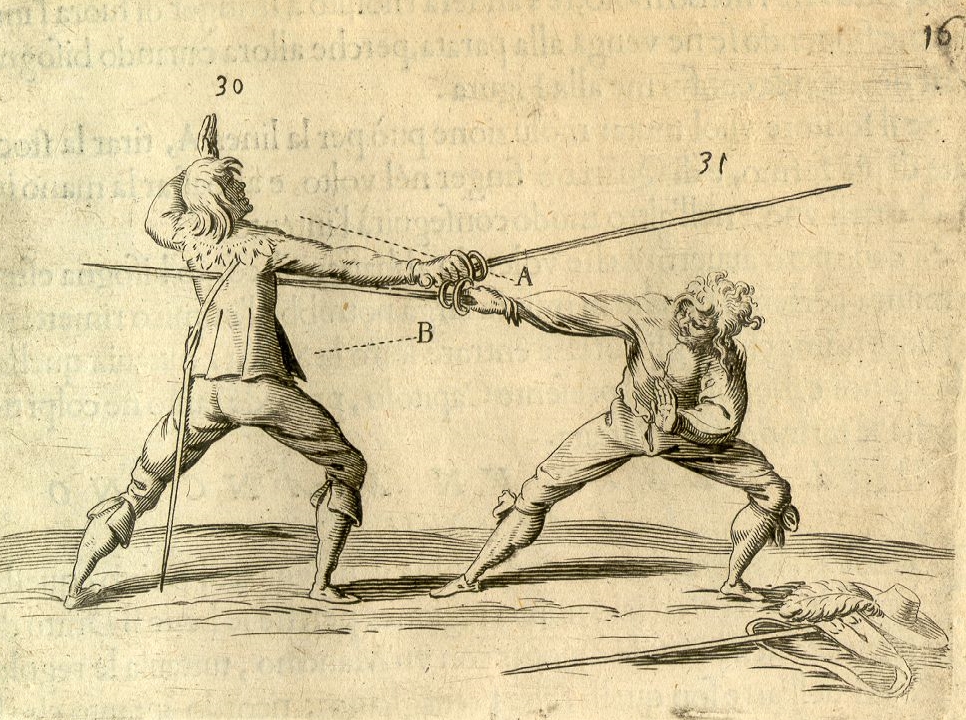

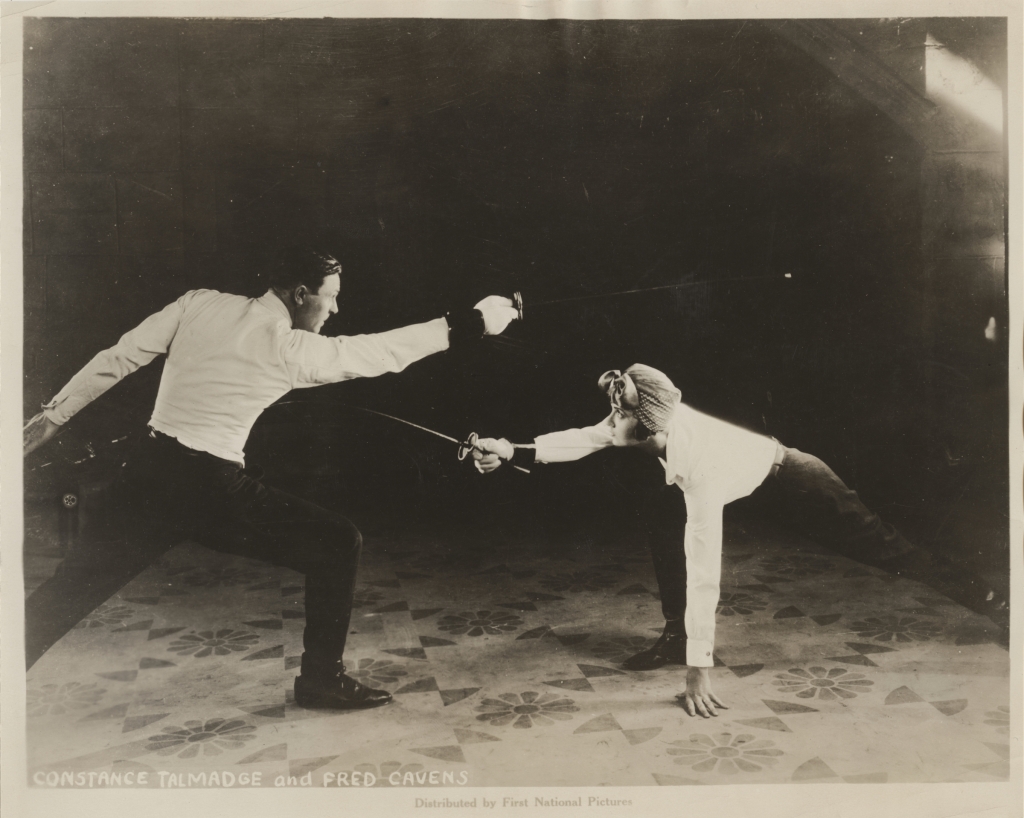

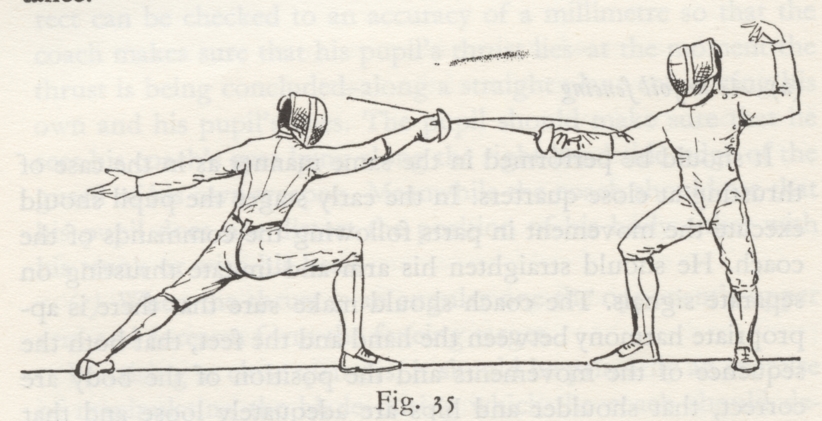

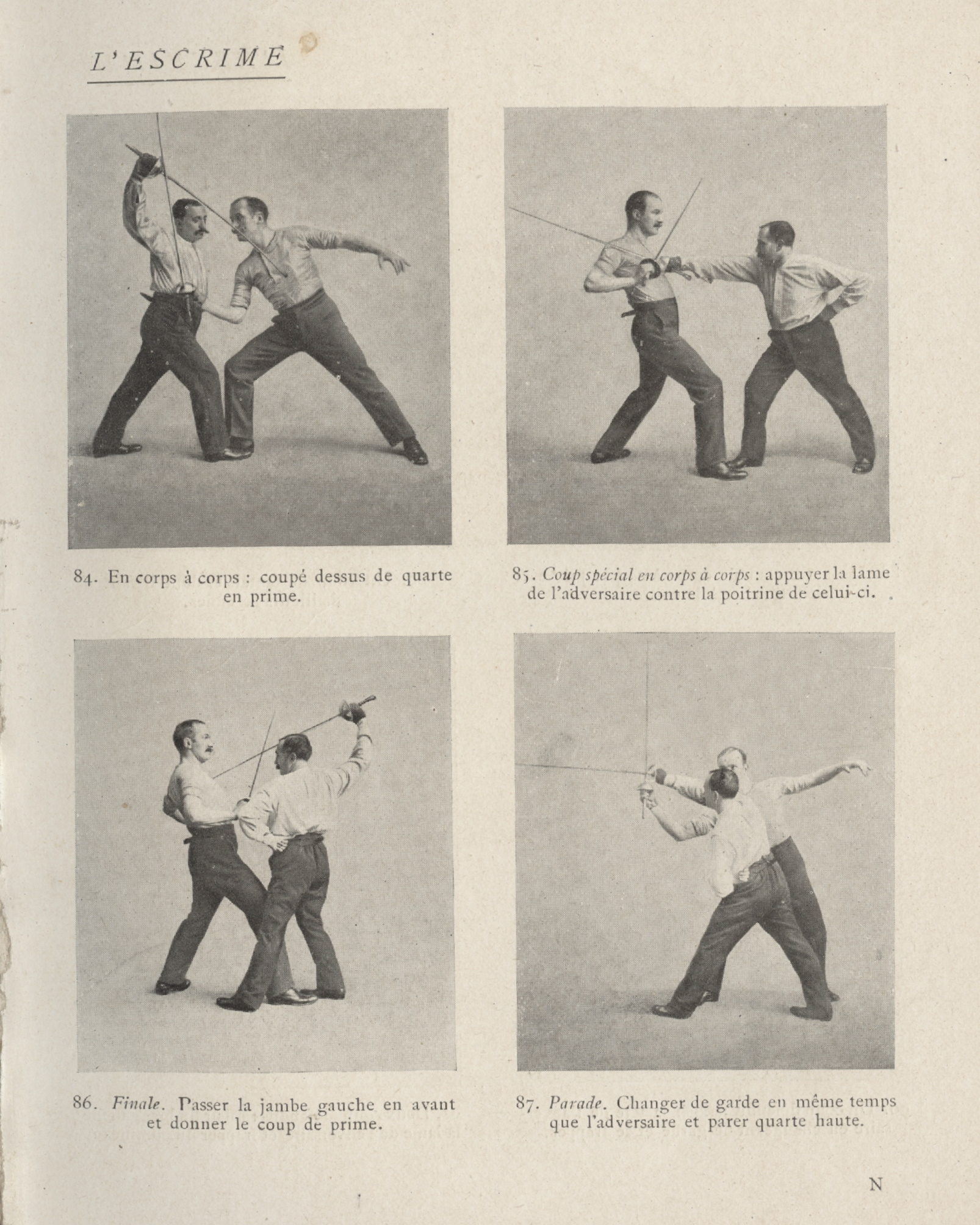

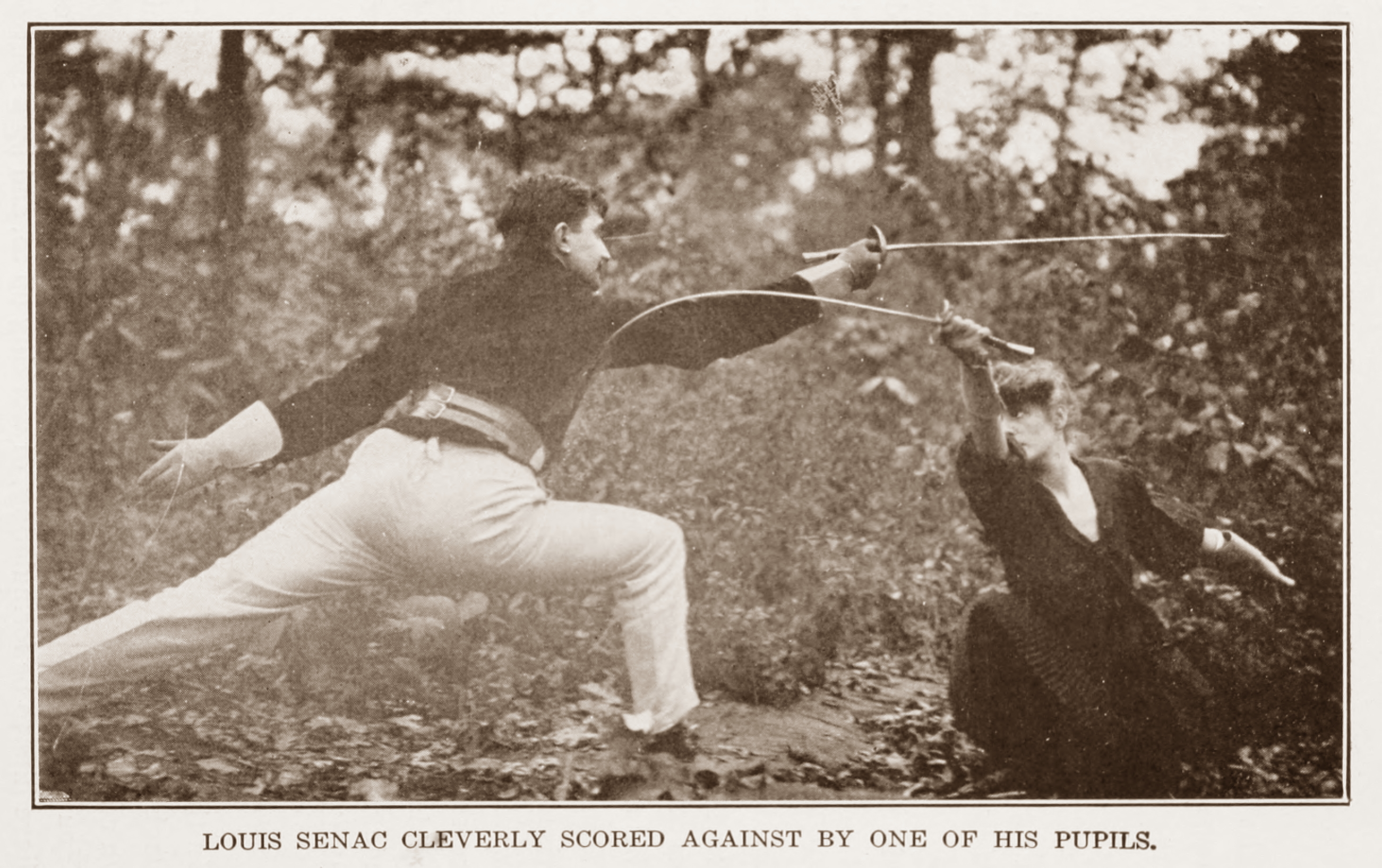

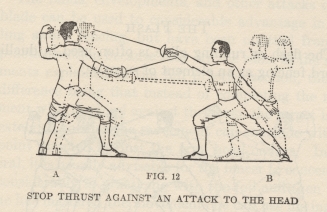

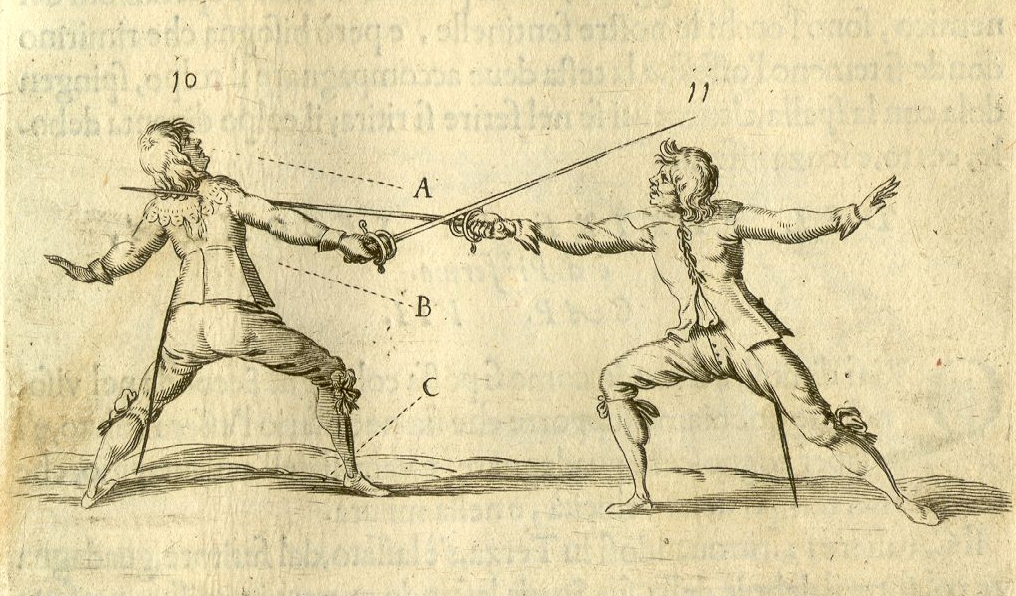

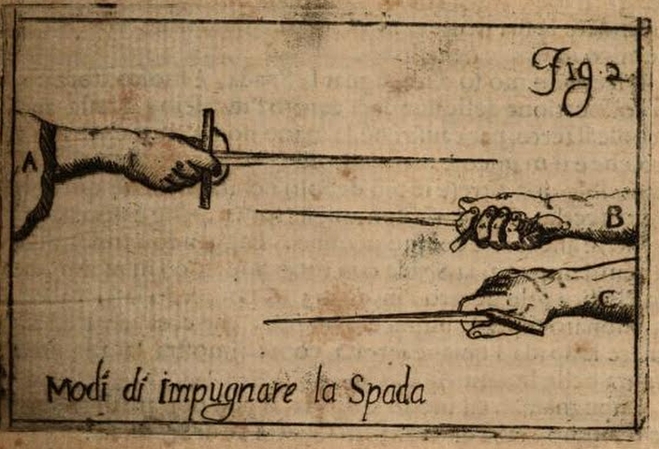

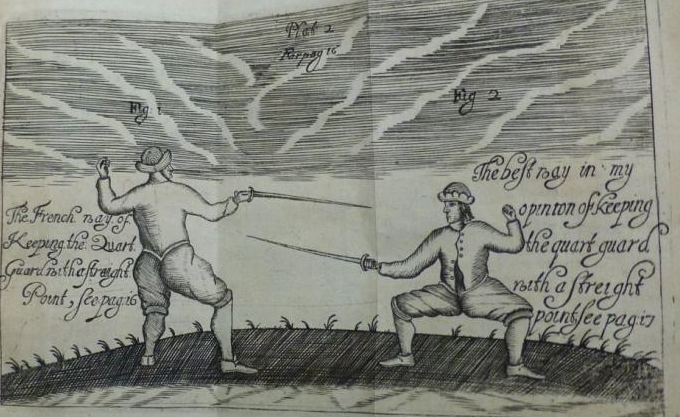

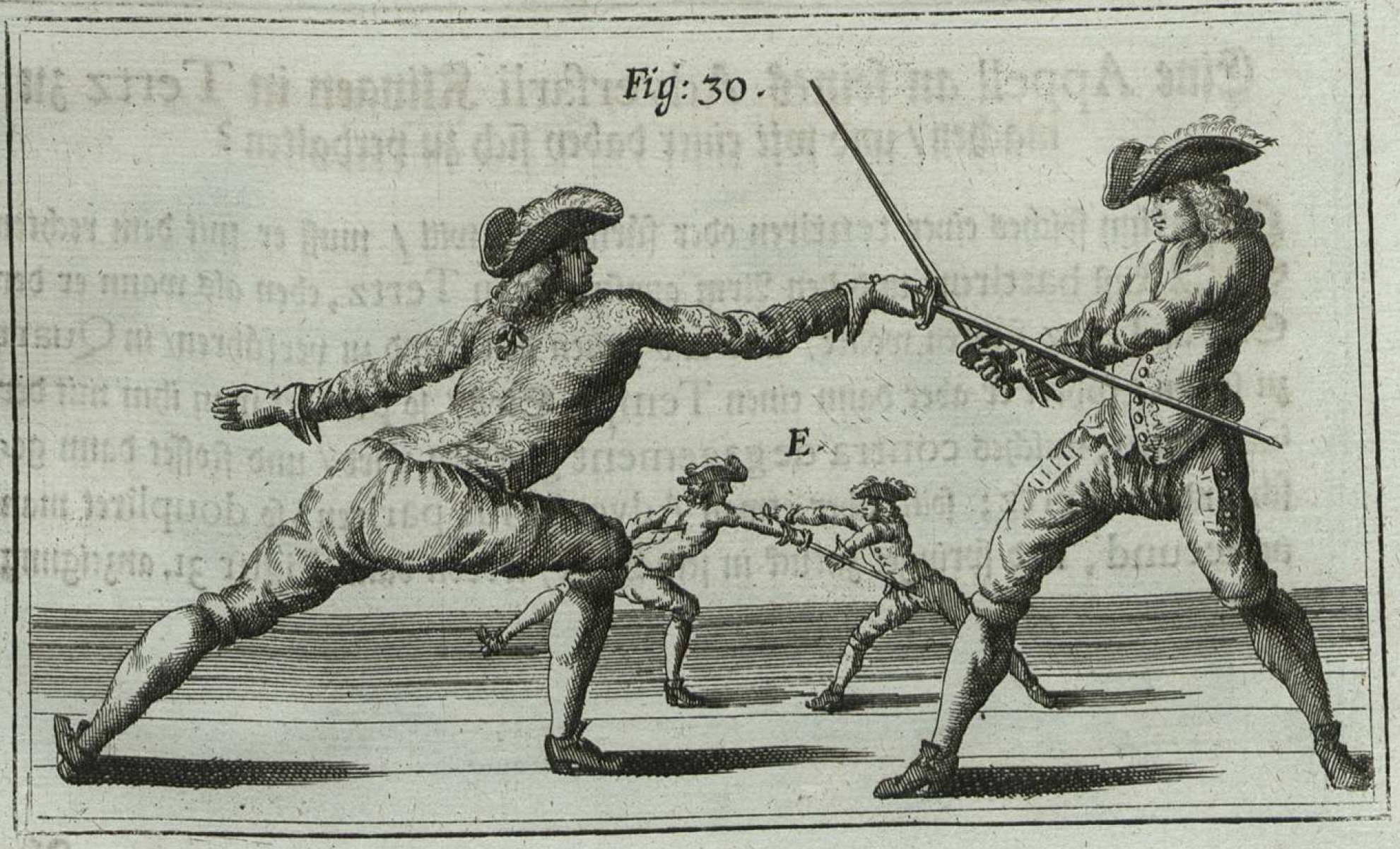

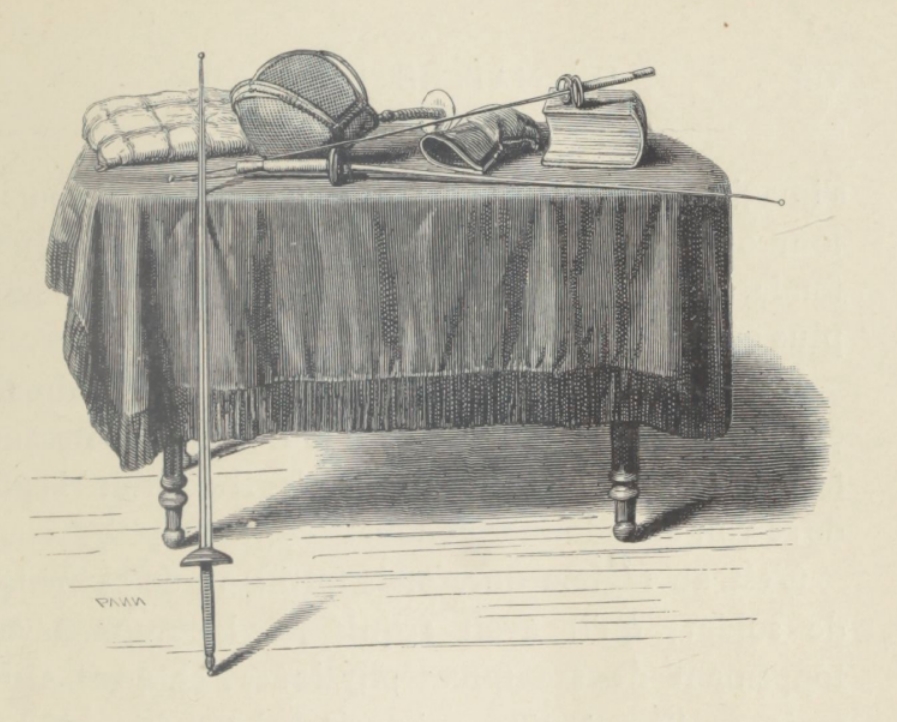

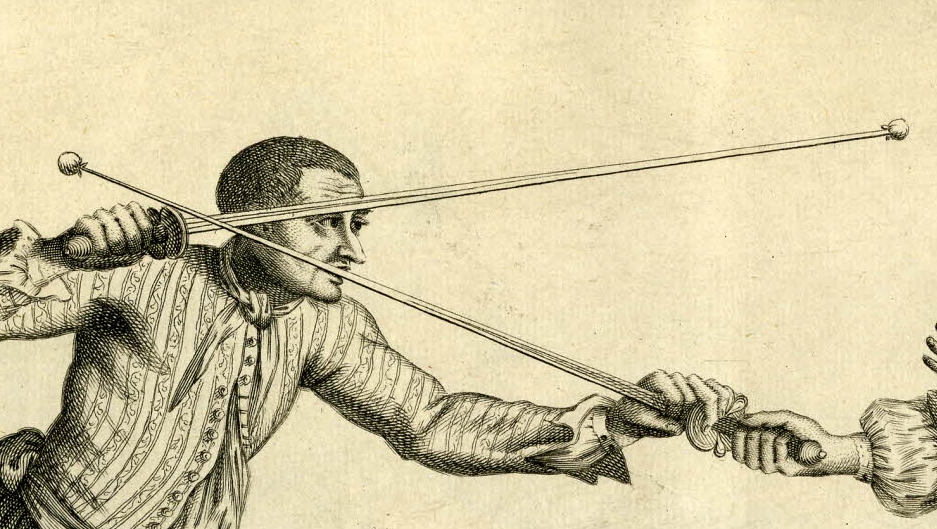

The Classic Passata Soto or “Night Thrust”

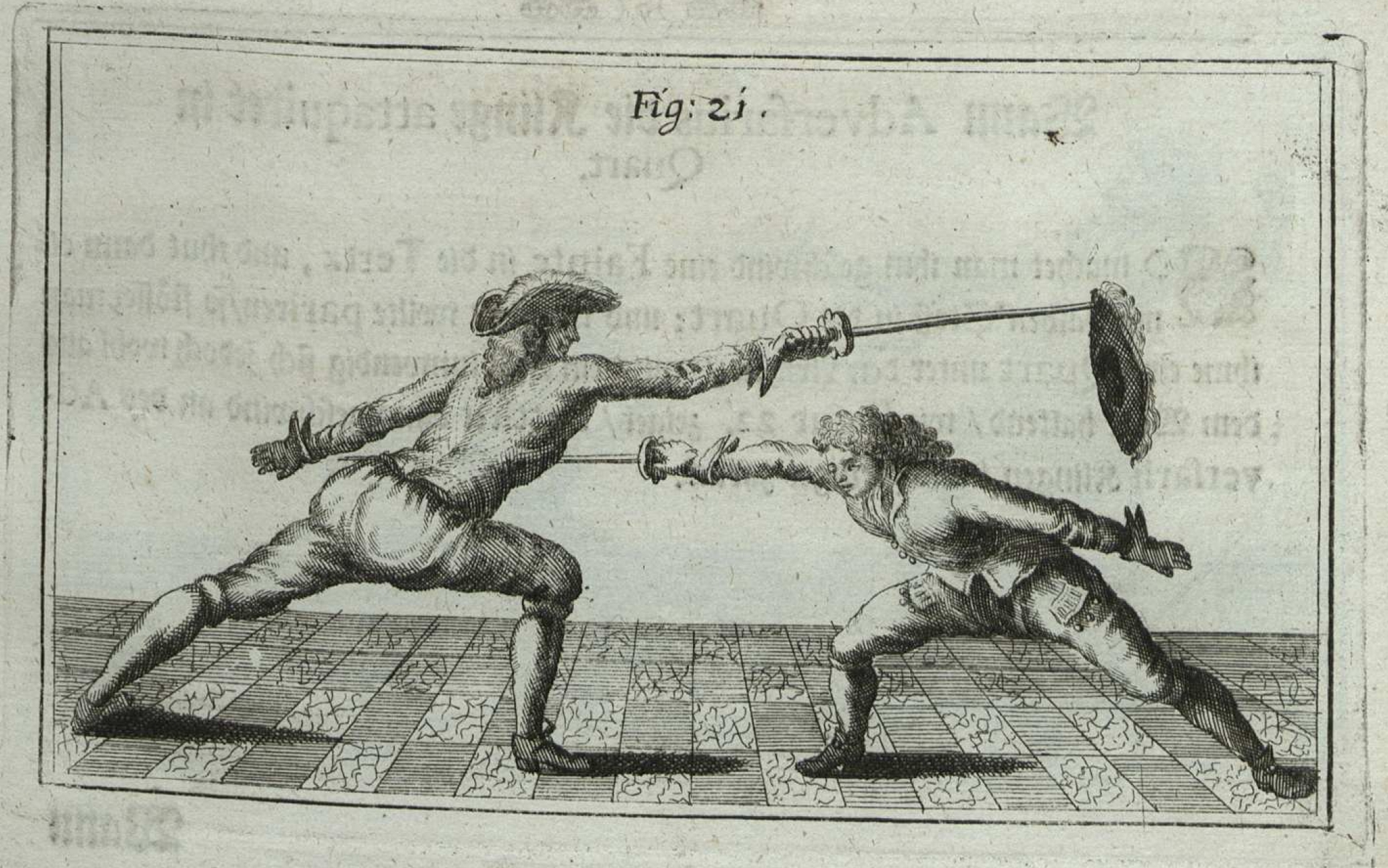

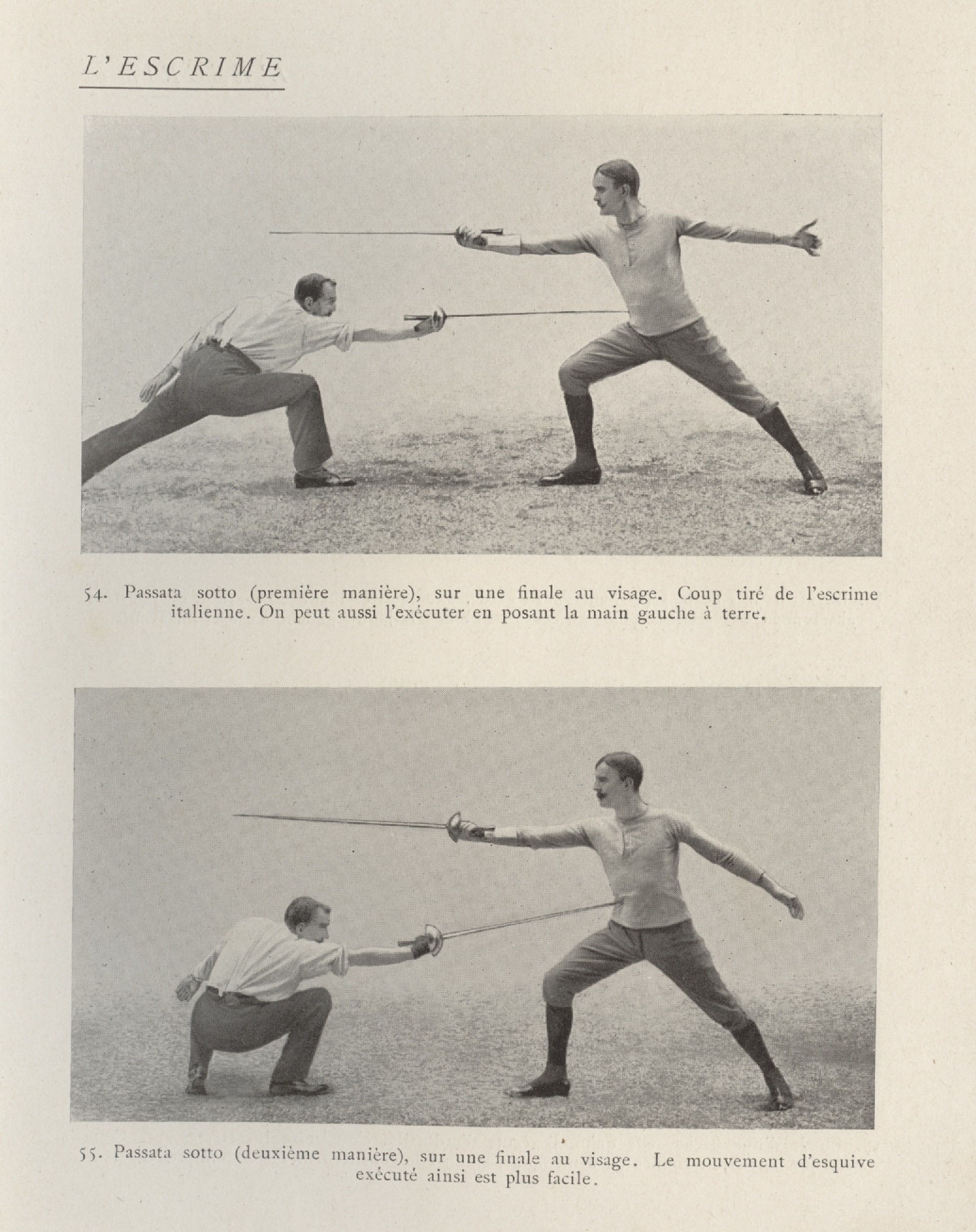

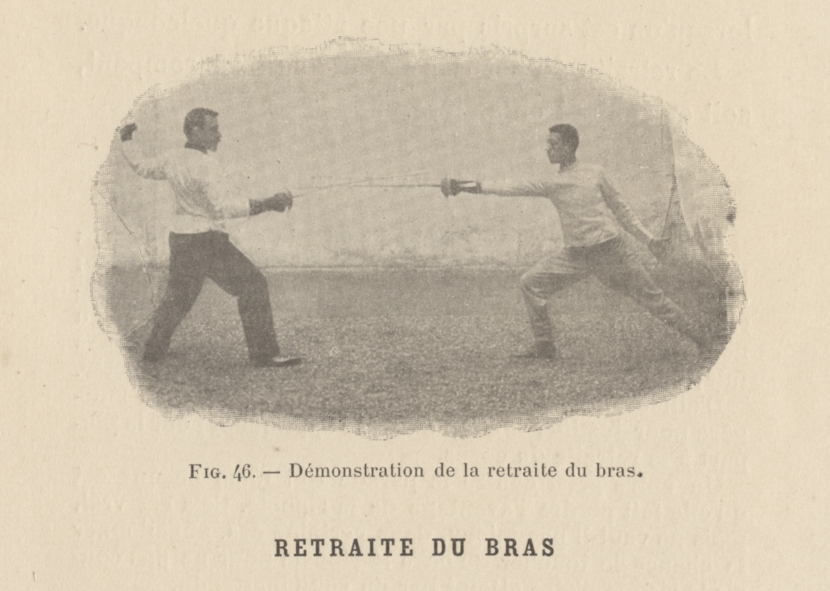

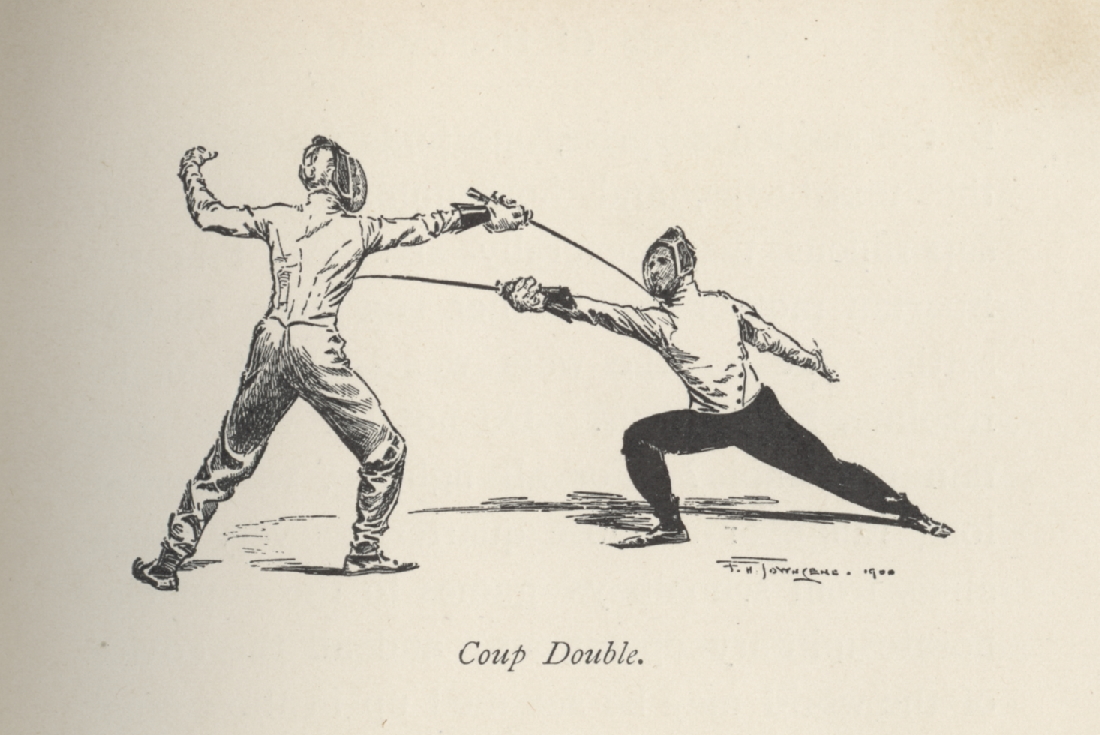

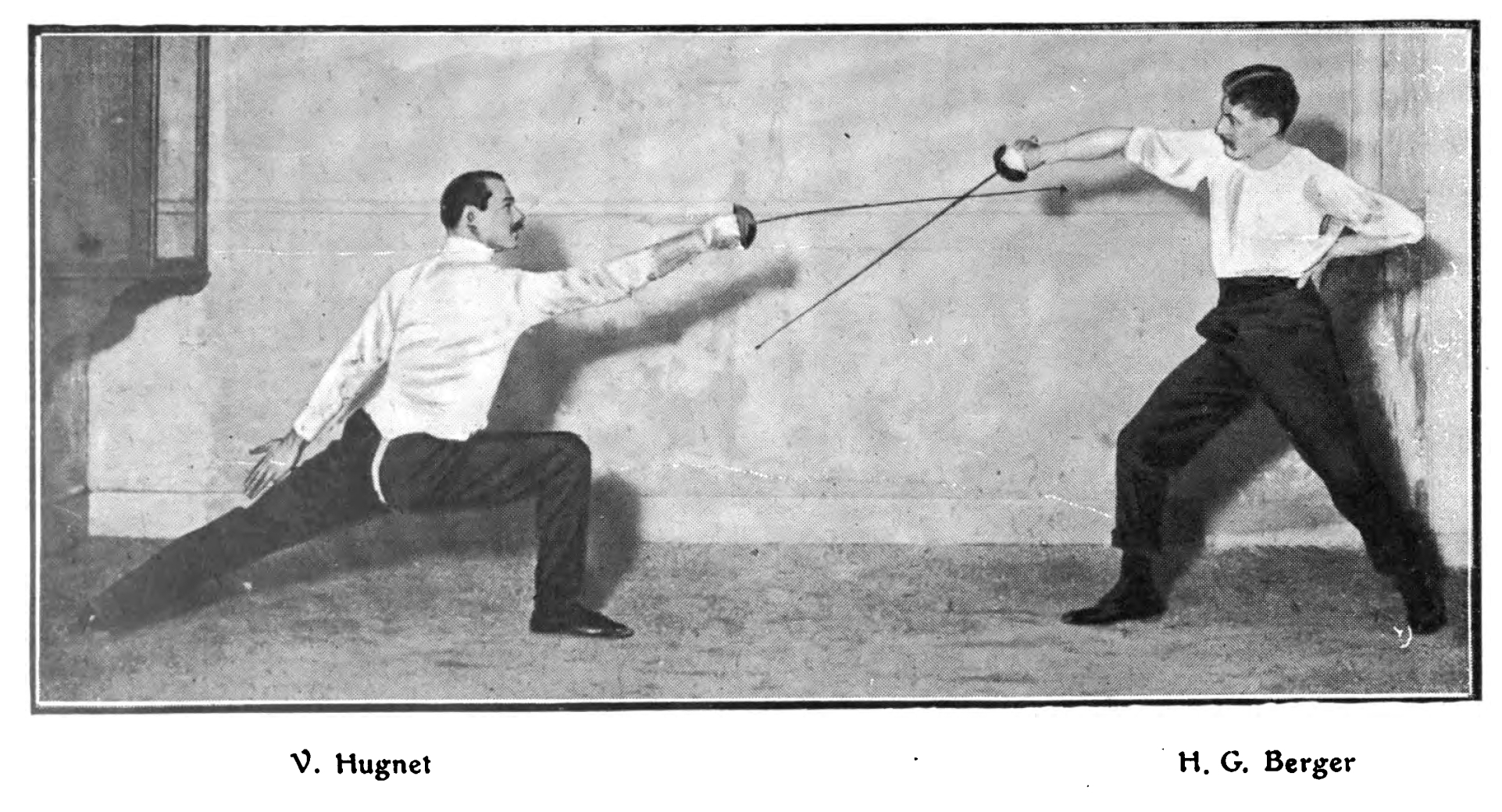

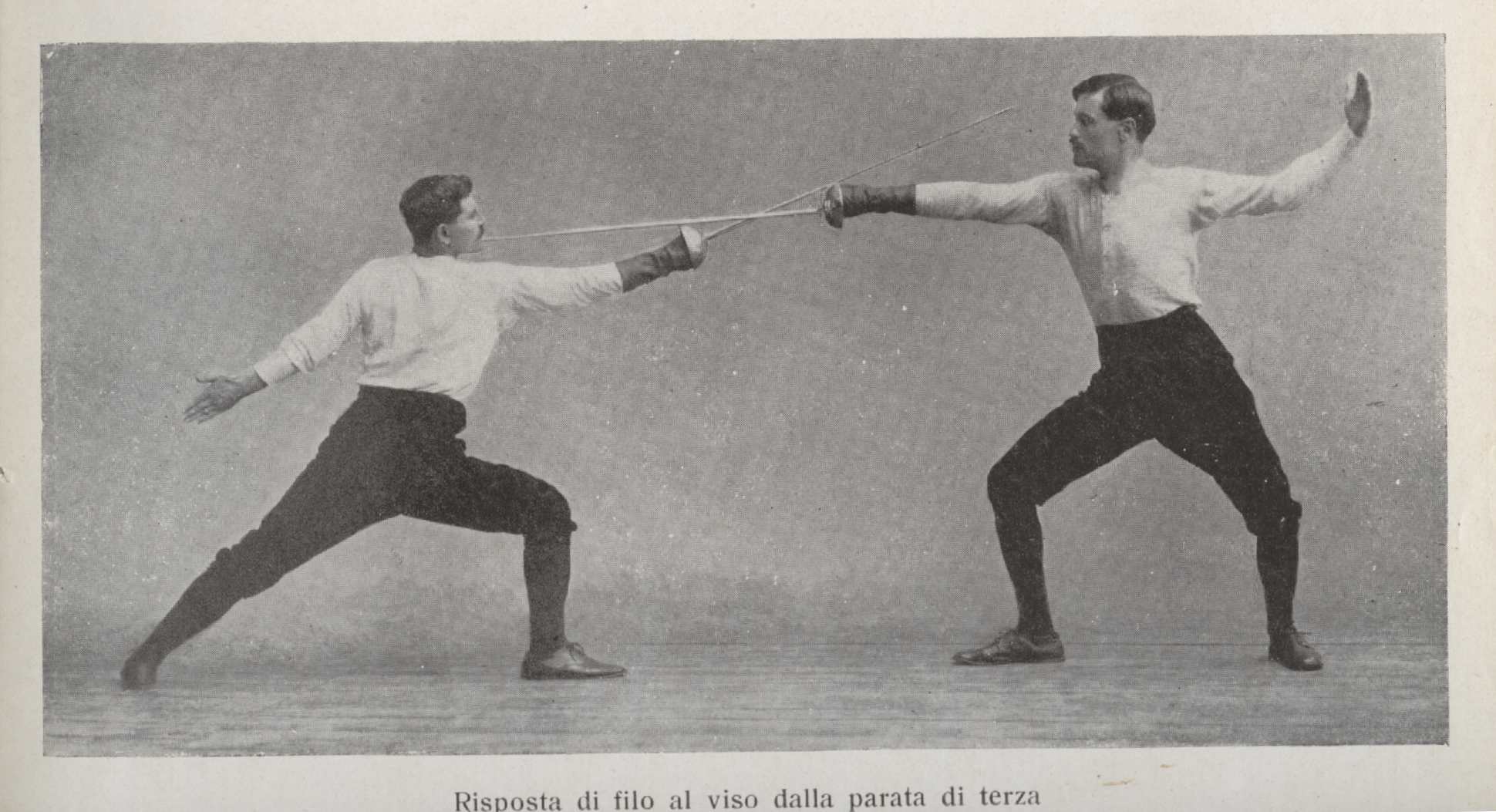

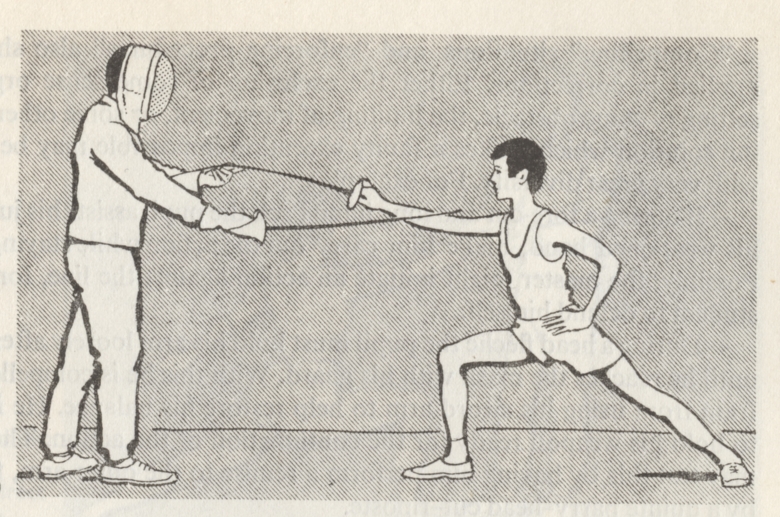

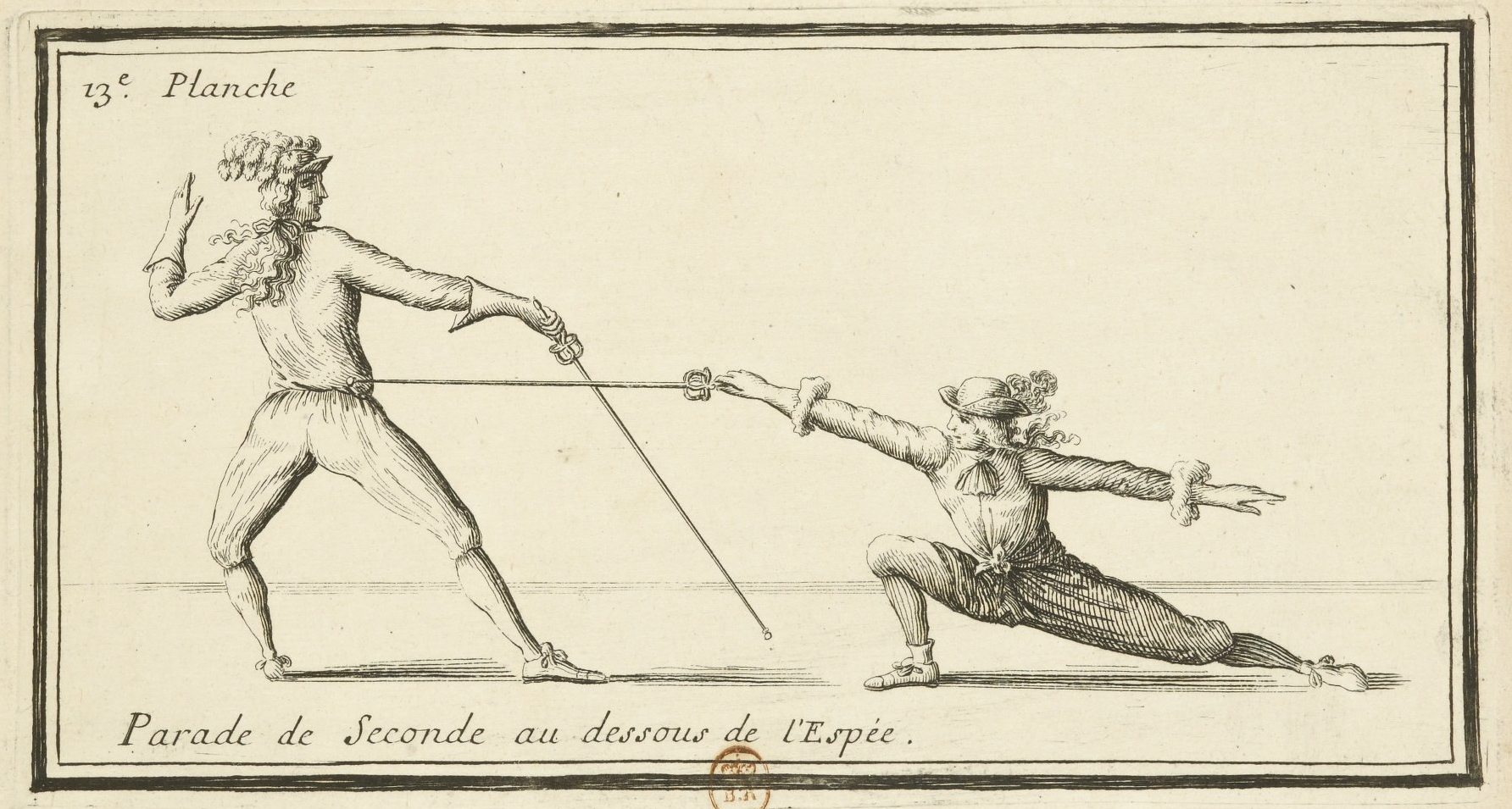

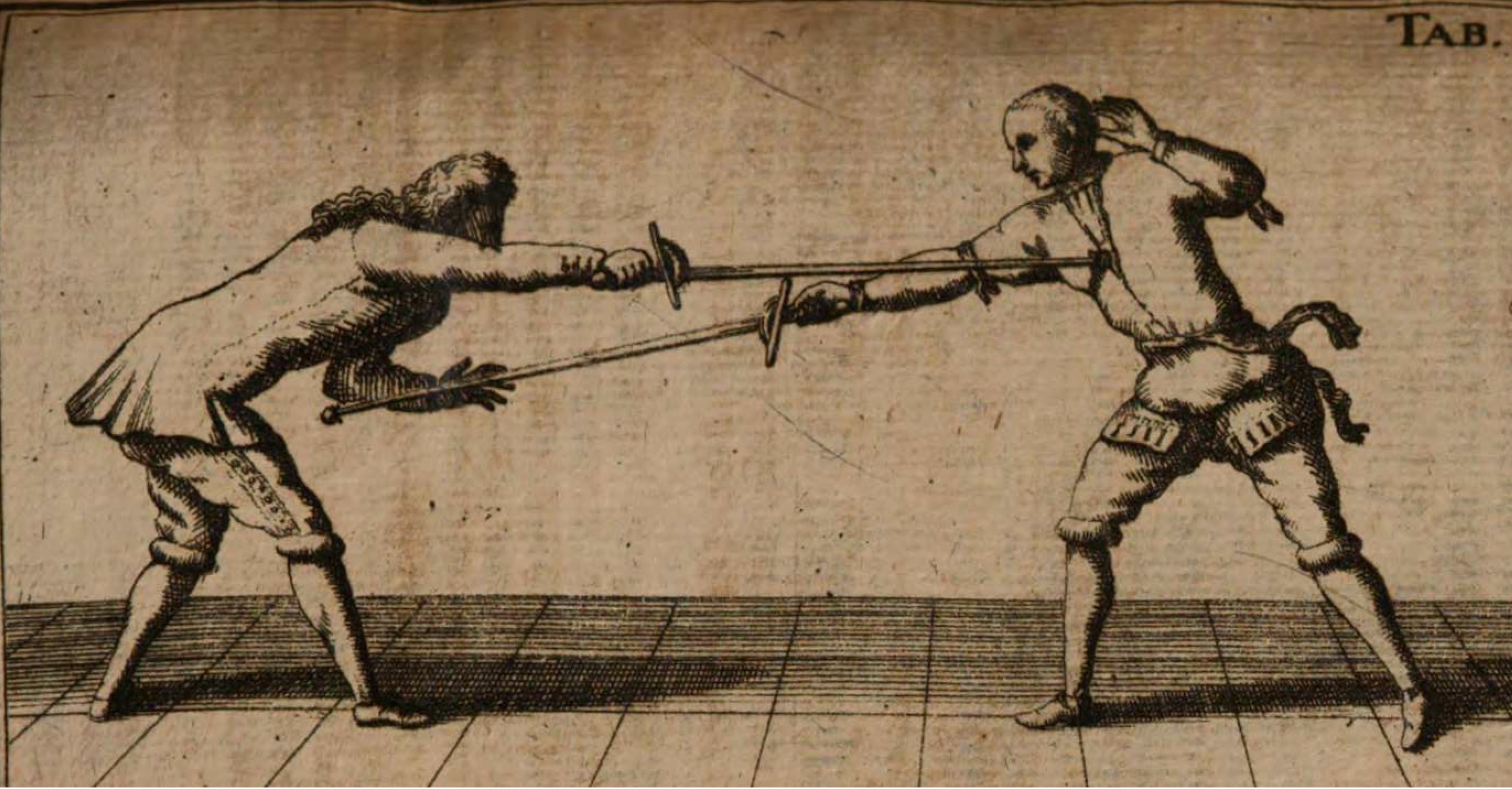

A staple of many Western fencing texts since the Renaissance, the passata soto, or passata sotto, also known variously as the sbasso, sottobotta, and cartoccio on occasion, the various dessous of the French masters of the smallsword and the passata di sotto of the modern, is usually defined as a counter-attack made by lowering the body while simultaneously thrusting, extending the rear foot in a reverse lunge, and placing the unarmed hand on the ground for support. Occasionally the technique is recommended as an attack with a true lunge, rather than a reverse. Andrew Lonergan provides an eighteenth century definition and exercise of the passata soto under the name of night thrust:

“On Guard in Quarte; and disengage a Quarte-over-the-arm [modern sixte]. I now batter [beat] with a Tierce; and begin to advance my left foot to form my Pass upon you in Tierce. Now when you see my left foot move, slip your left foot back, so as to pitch yourself on that knee; stoop your head so that your arm now turned into a Segonde may cover it, hold your left hand extended toward the ground, that it may sustain you, in case you should totter; thus my point will pass over your head, and I shall fall upon yours.”

And his reasoning why such “athletic” techniques should not be abandoned:

“Though these methods of Disarming, and Passing, Volting, and that of the Night Thrust, seem to be almost abolished by the refiners of these arts; I cannot conceive why a man, who is naturally strong and active, should not avail himself of such advantages, especially when improved by our athletic exercises, so engaging to an English subject, and forbidding to all others.”

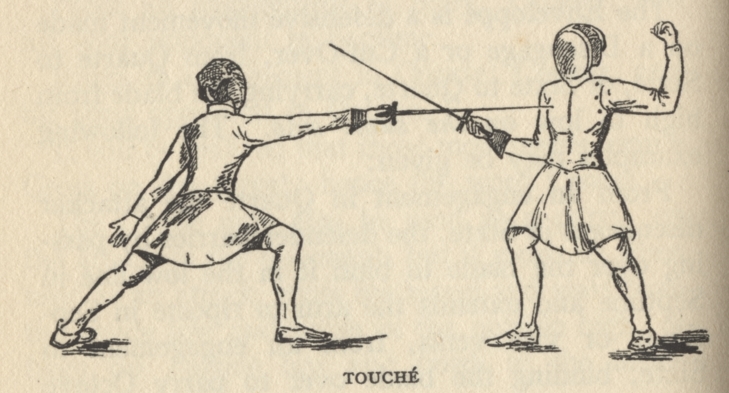

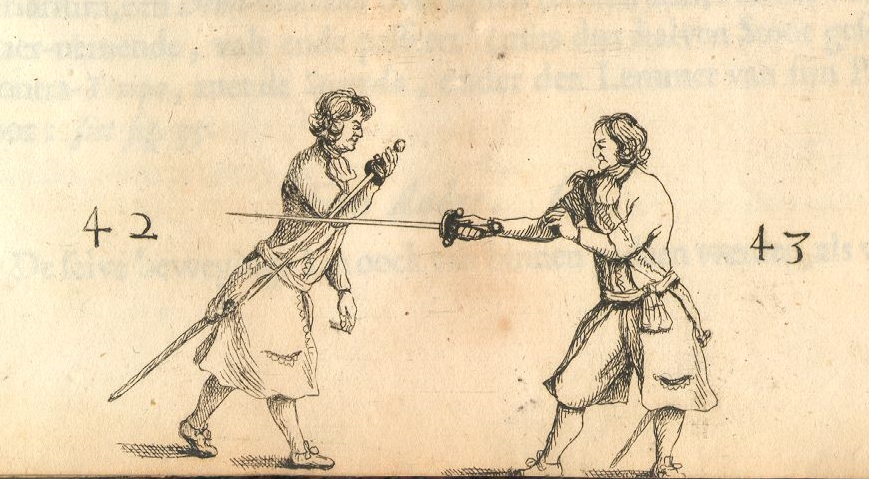

In the old Italian schools, the body was usually bent at the waist. In some of the old French, the body was lowered by a very low reverse lunge. The adversary may be hit either with the extending arm or by impaling upon it, or both.

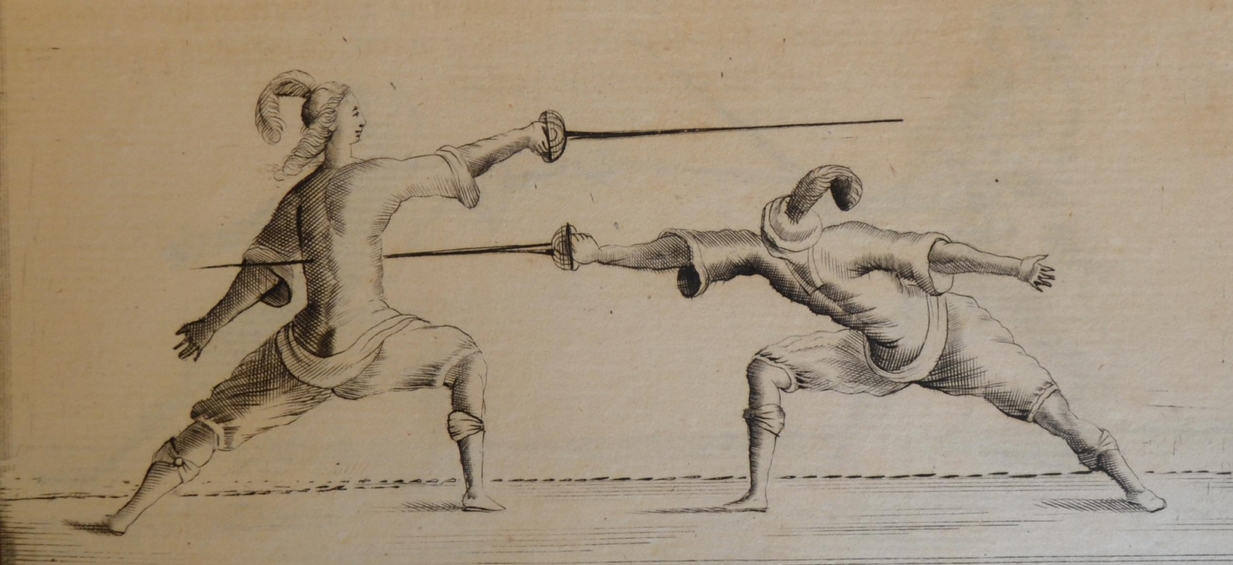

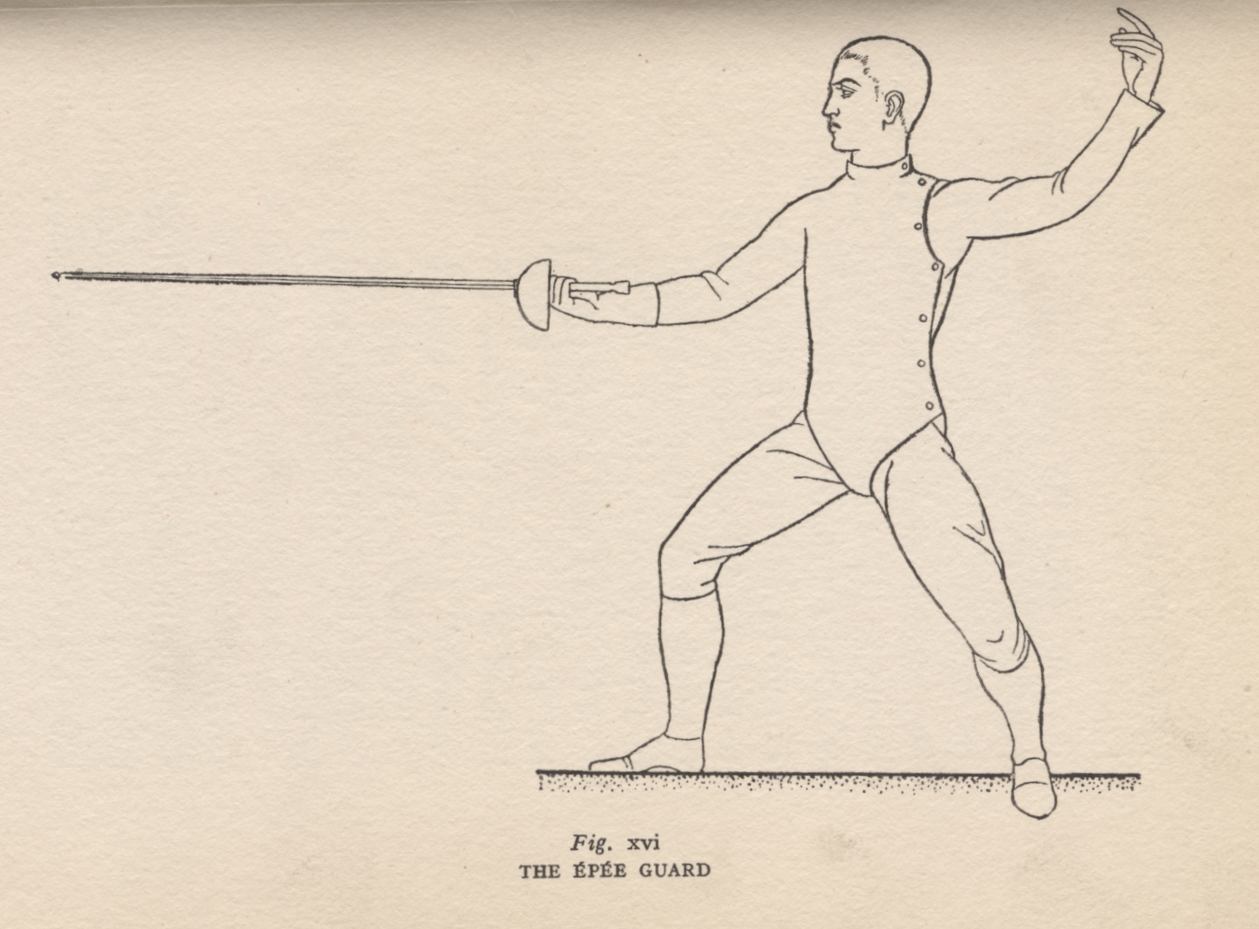

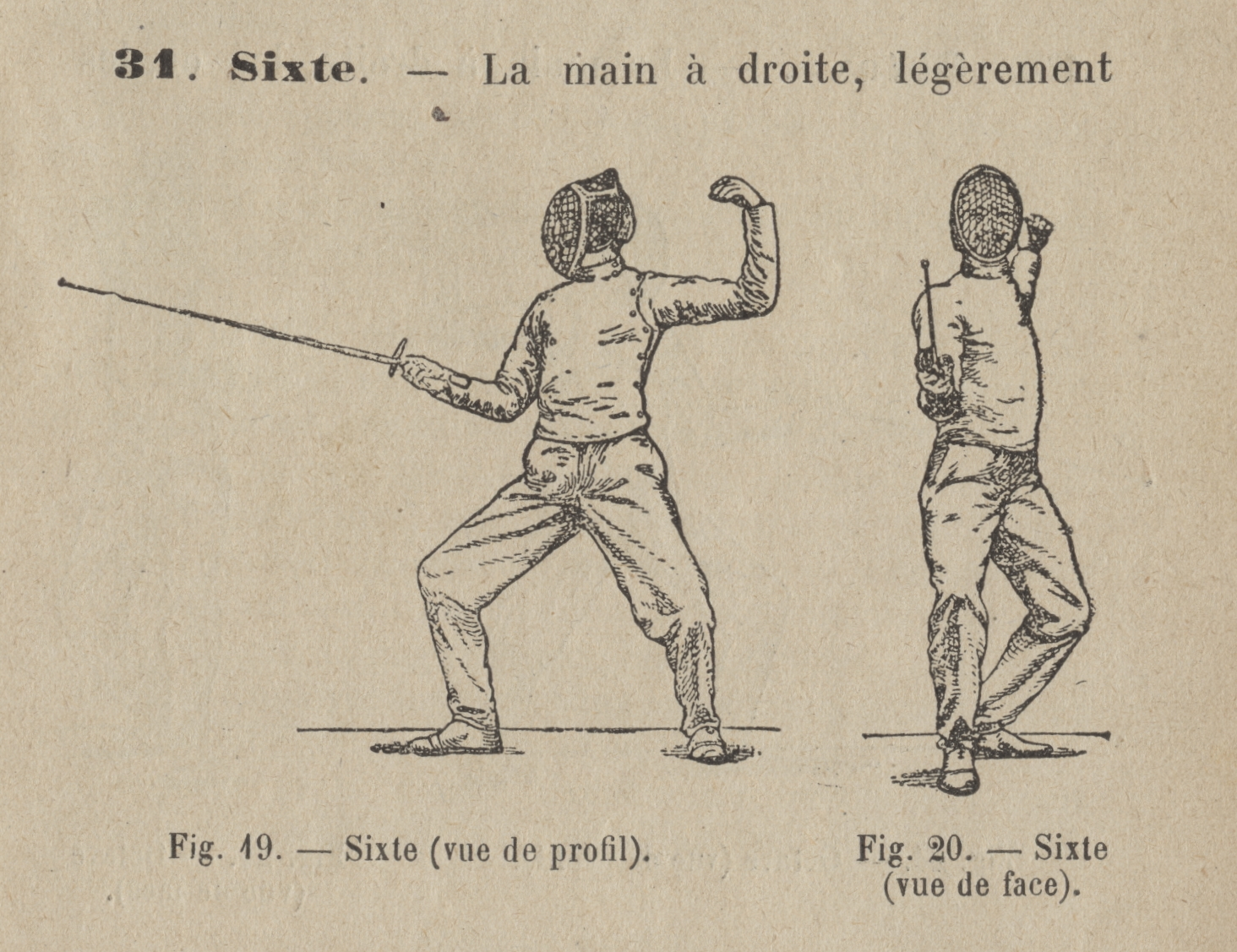

In terms of the modern French school, the “passata di sotto” is classified as an esquive, specifically une passe dessous with the back leg extended or both legs deeply bent.

With real weapons, the adversary is ideally impaled, usually in the belly which is, were the swords real, a good place to hit because there are no ribs and cartilage to potentially prevent the point from entering or otherwise diminish its penetration. There is also some anecdotal evidence to suggest that in some cases belly wounds may be more quickly incapacitating.

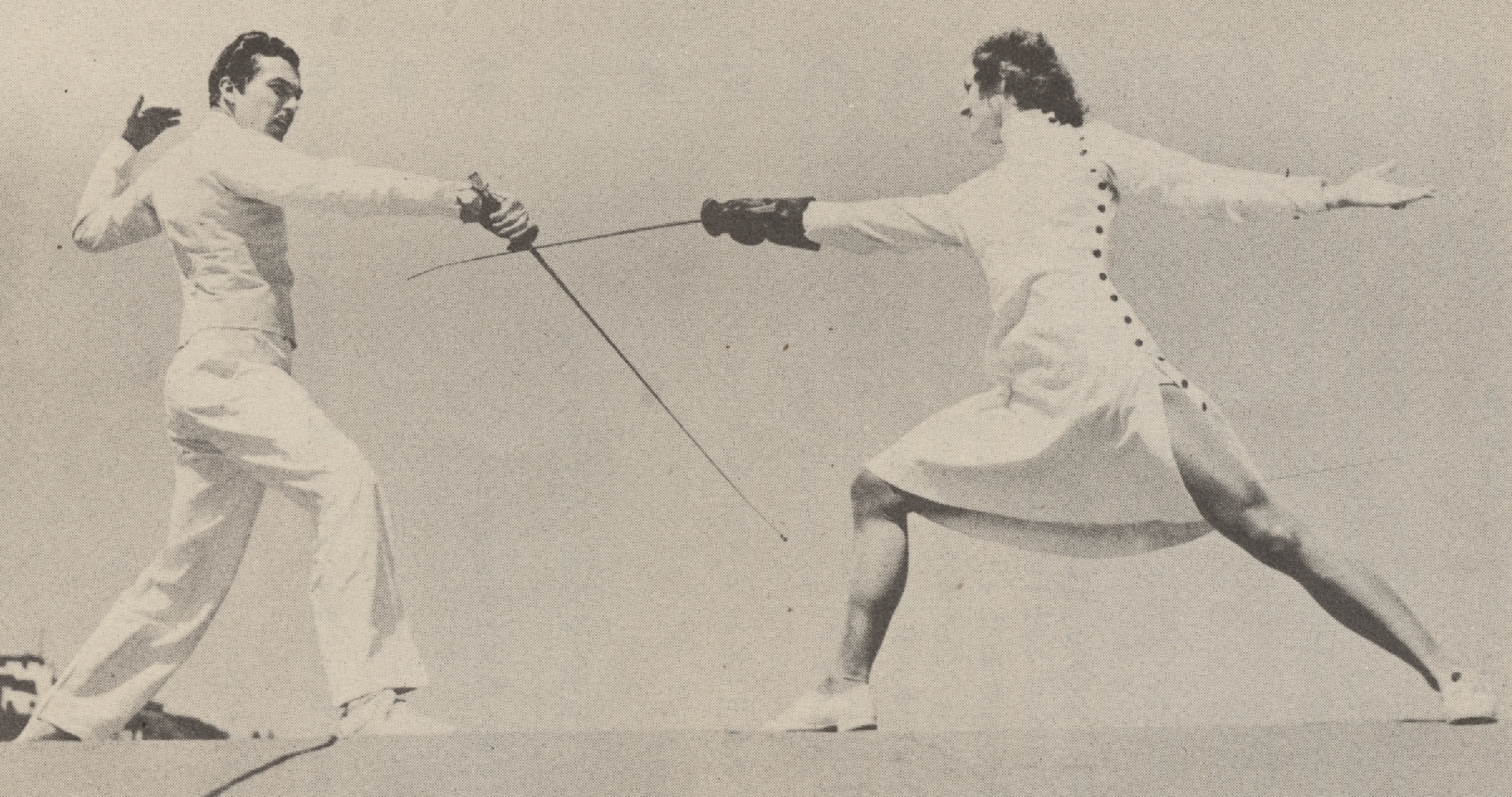

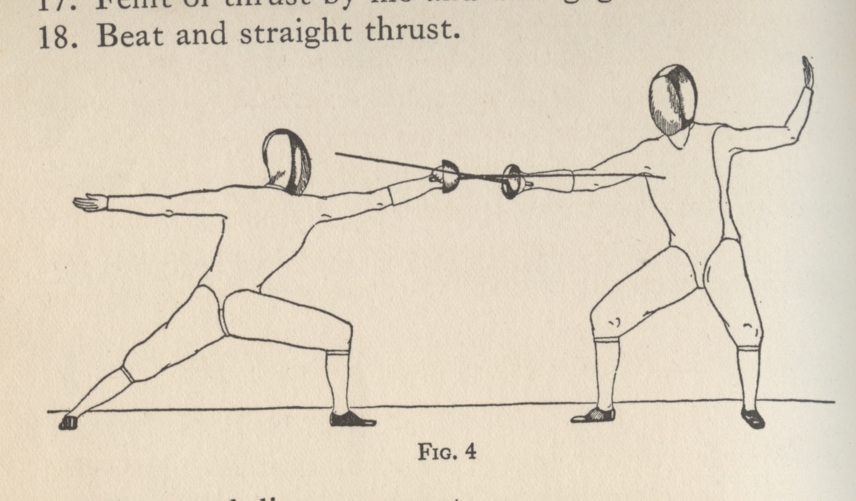

A very long low lunge which made going forward might slip under the adversary’s guard, as in Rafael Sabatini’s novel The Black Swan (1932), and which made in reverse might serve aid a counter-attack by lowering of the body. (An analysis of the duel in the novel may be found here: The Duel on the Beach, Part II: The Black Swan.)

Long low lunges like this are often identified with, or confused with, the passata soto. Note, however, that fencing language is highly malleable and definitions vary: one master’s passata soto might include only the classic reverse lunge with a bend at the waist, while another’s may include any lowering of the body in attack or counter-attack. Most masters, however, consider it to be a counter-attack with esquive, the body lowering in place or with a reverse lunge, and not a long low lunge forward.

The passata soto is not without significant drawbacks, which is probably why Lonergan recommended its use at night and nowhere else. Foremost, it must be well-timed. Too late, and the fencer attempting it may get hit in the face, neck, or upper torso. Too soon, and the fencer attempting it throws away the advantage of the surprise mandatory to its success. Used too often, and the adversary may learn how to trigger it with a feint, and then take advantage of the poor position the classical passata soto leaves the fencer in.

And it is this poor position that is the major drawback of the passata soto, in particular with real weapons. With the unarmed hand on the ground, the torso bent sideways, and the rear leg extended well behind, the fencer is in a bad position for defense after a failed attack or, even if the swords were real, after impaling the adversary. Few wounds are immediately incapacitating, including ultimately fatal wounds: many duelists and battlefield swordsmen were wounded or killed after giving an adversary a fatal wound. Even with a mortal wound to the heart, an adversary may live as long as ten seconds. Even assuming an average of four, that’s plenty of time to even things up.

In the case of dry (non-electric) weapons, the judges and director (referee) will determine whether a hit was made, whether it was in time, and whether a hit on the fencer who ducked is valid via rules regarding replacing of target. In the case of electrical weapons, the machine will make the determination in epee, and the machine and director in foil and saber.

For the fencer armed with a rapier on poniard, placing the poniard-armed hand on the ground is giving up half of one’s offense and defense, to be replaced by almost blind trust.

From the position of the passata soto, a prime or lifted sixte/septime beat or bind, or a St. George parry or opposition (modern saber quinte) accompanied by the use of the unarmed hand to help ward off the adversary’s blade, plus an urgent recovery forward or backward, all performed near-simultaneously, is the only viable option if the passata soto has failed to hit or otherwise halt the adversary.

Such recovery, however, is invariably slow, and a loss of balance may ensue if the unarmed hand is removed from the ground too soon to assist in parrying or opposing, for example. Further, the long low position leaves the fencer vulnerable if the arrest fails, whether by missing the adversary or failing to immediately incapacitate him. In particular, the head, neck, and subclavian area are exposed. Fatal thrusting wounds can be given in any of the three areas. It’s likely that execution at night might alleviate some of these weaknesses in the technique, but it would need to be a dark night with little ambient light.

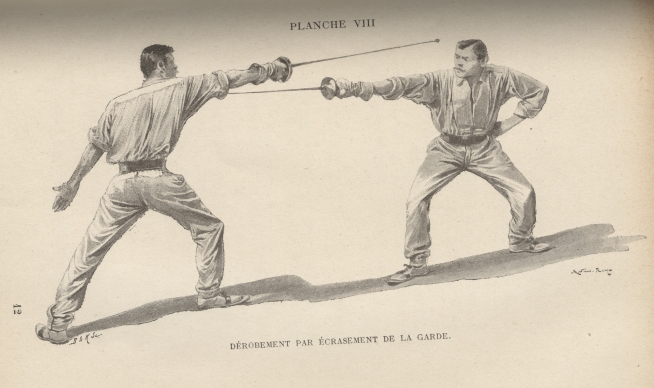

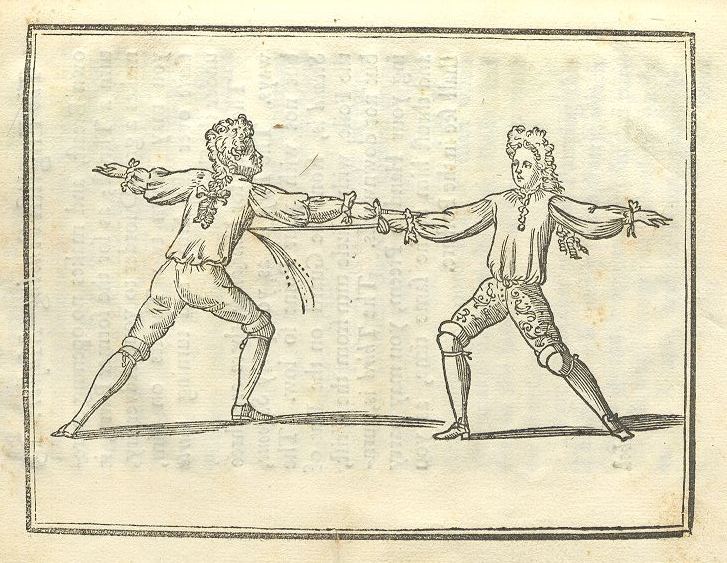

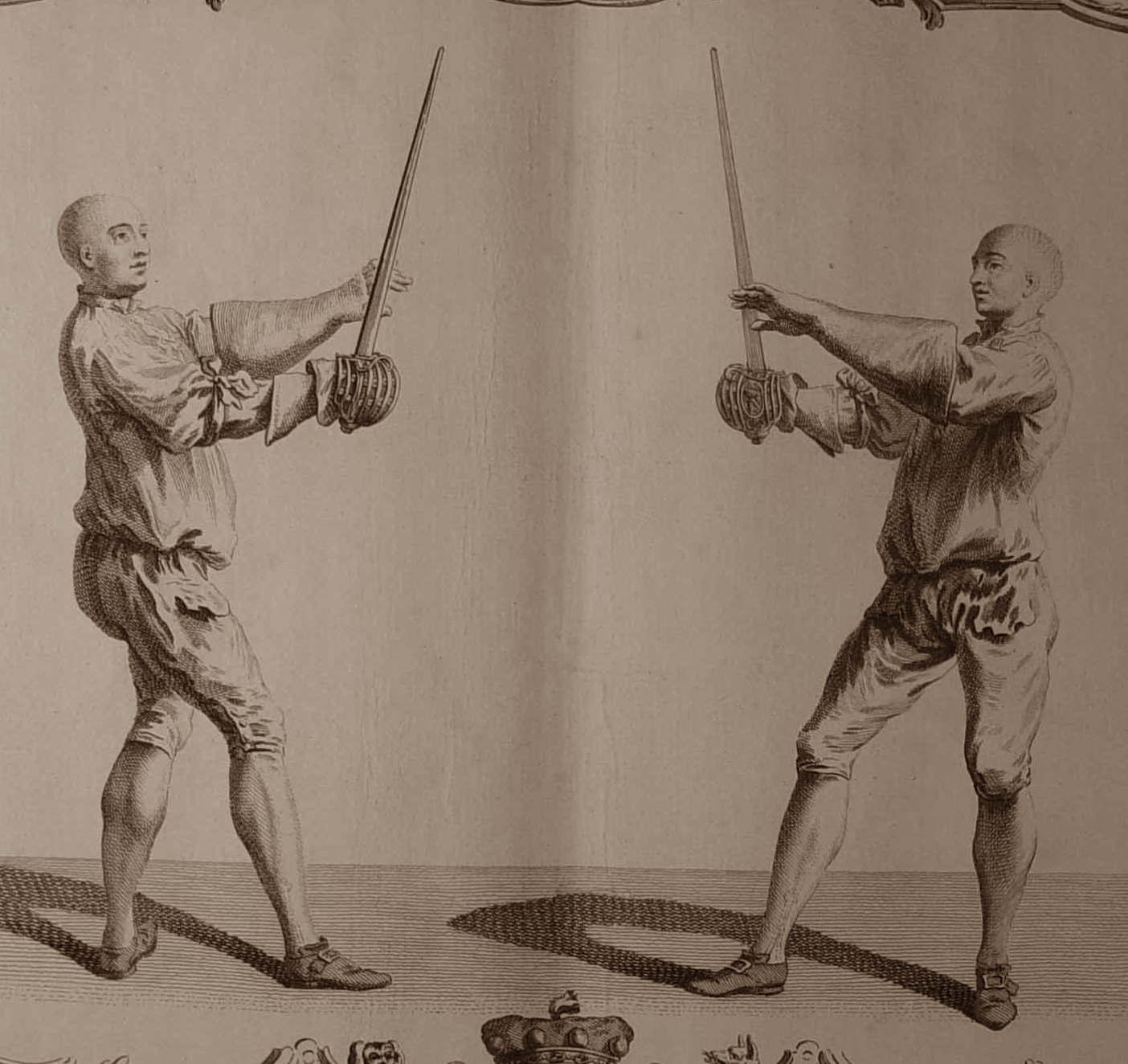

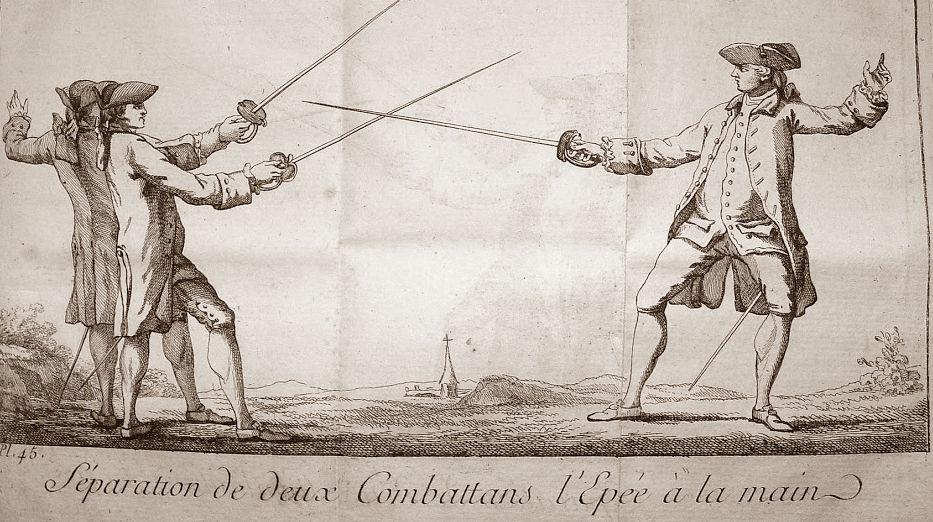

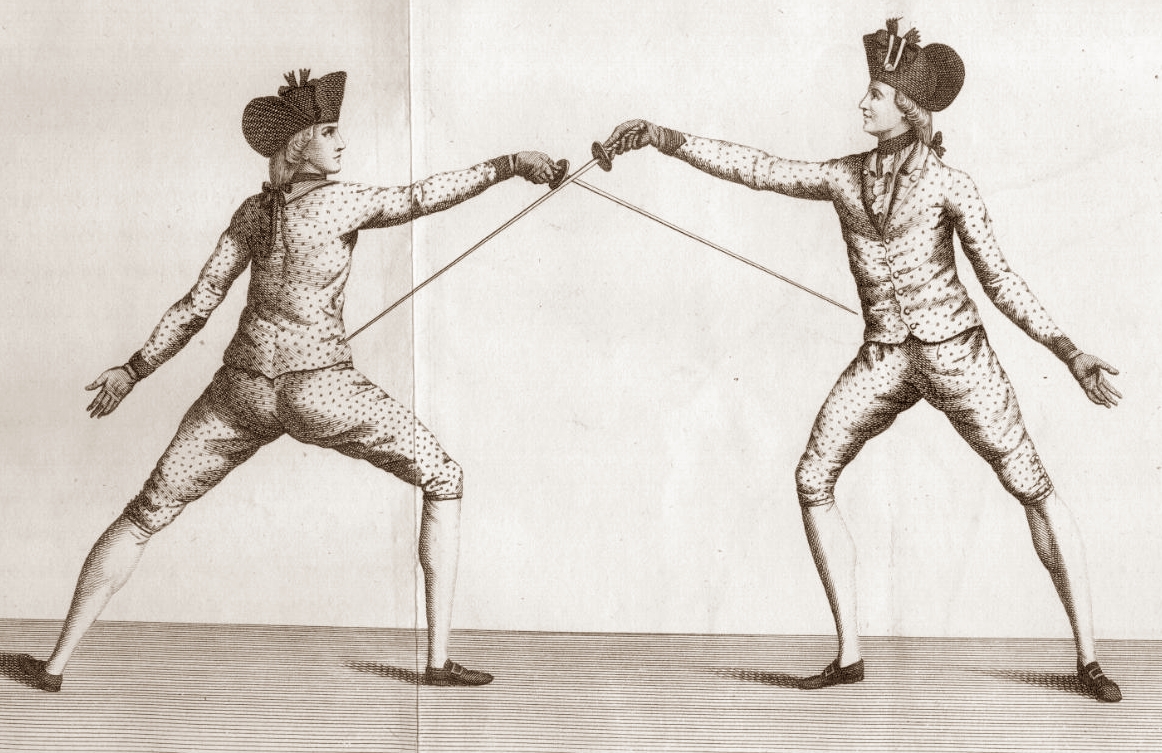

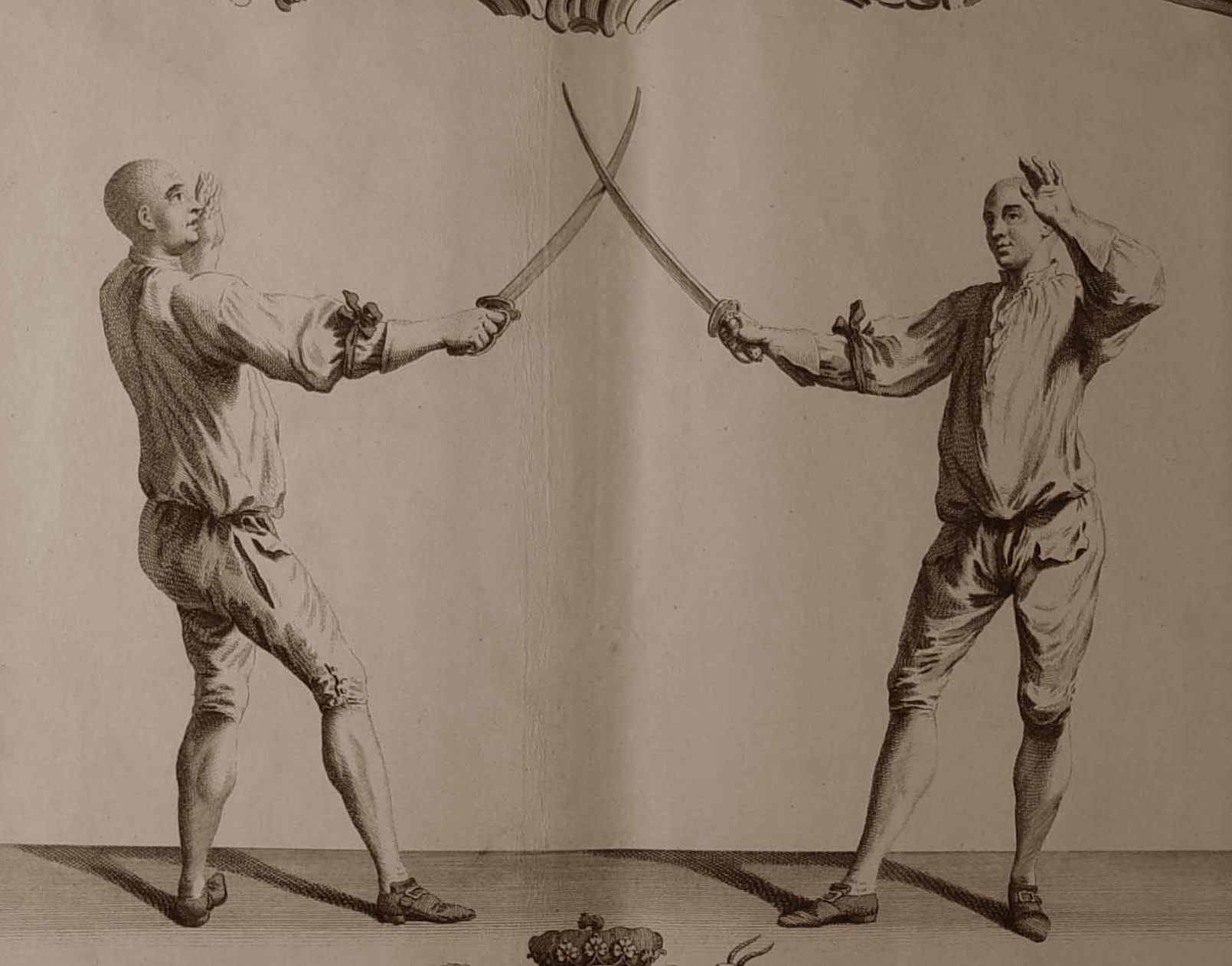

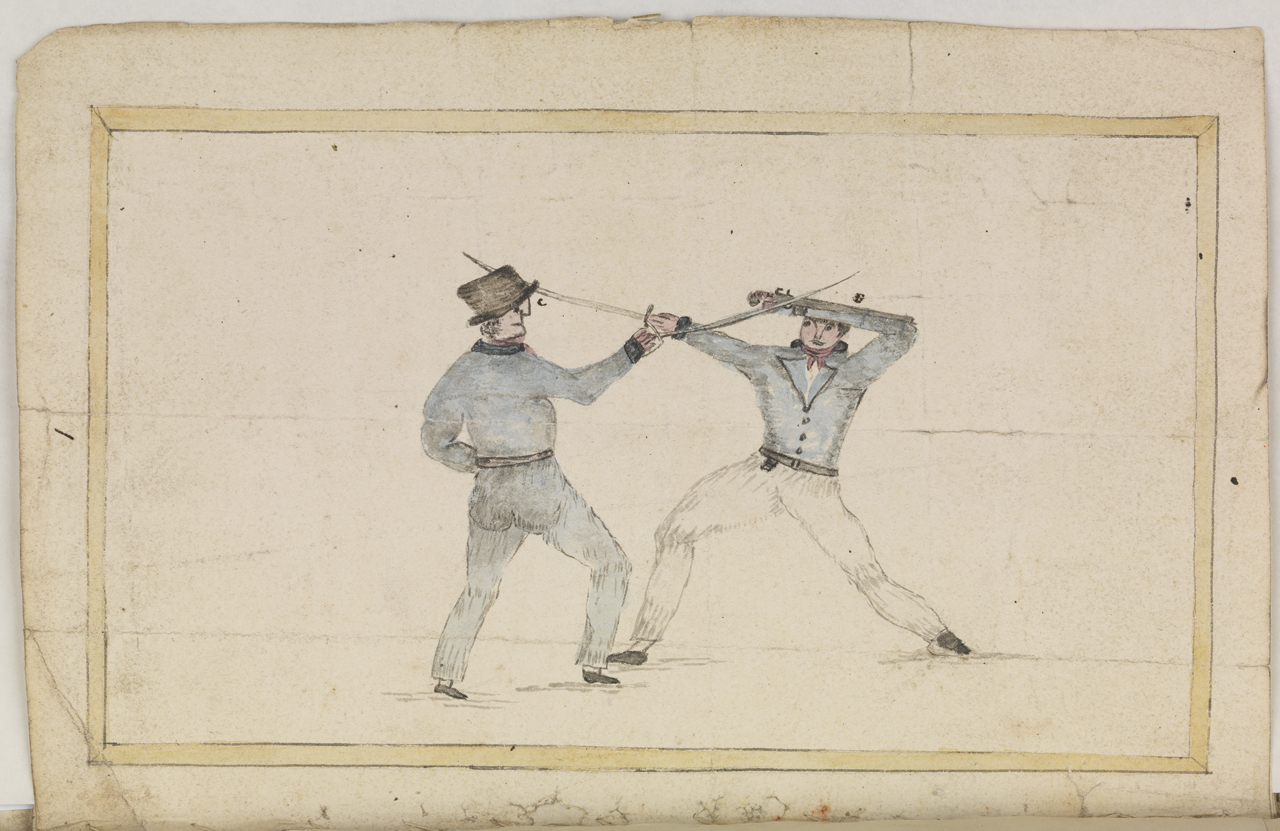

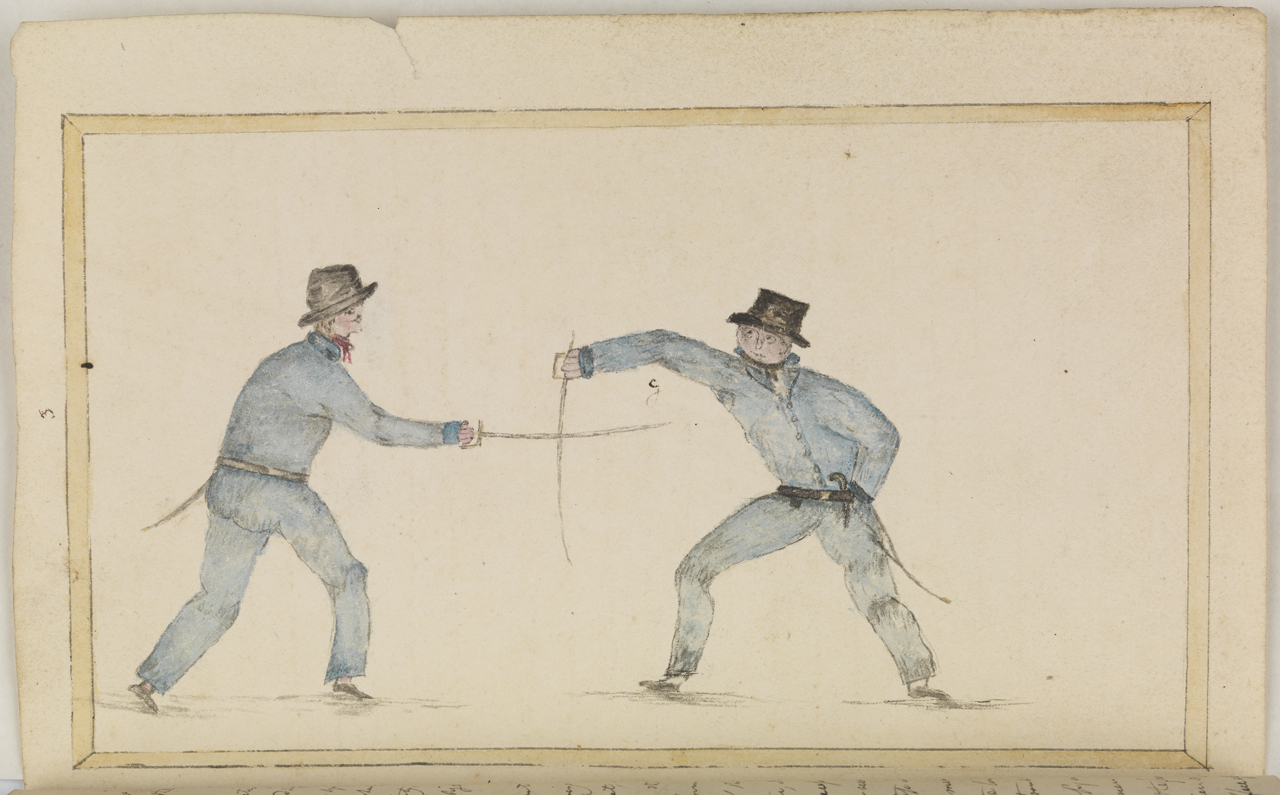

Historical Techniques Similar to Passata Soto

There are better methods, past and present. In particular, these methods, while not reducing the target quite as much, leave the fencer in a much better position should the counter-attack fail, or, with real weapons, should the adversary be hit but not be immediately incapacitated. Some masters, Sir William Hope for example, believed also that a lowered position better-protected the torso.

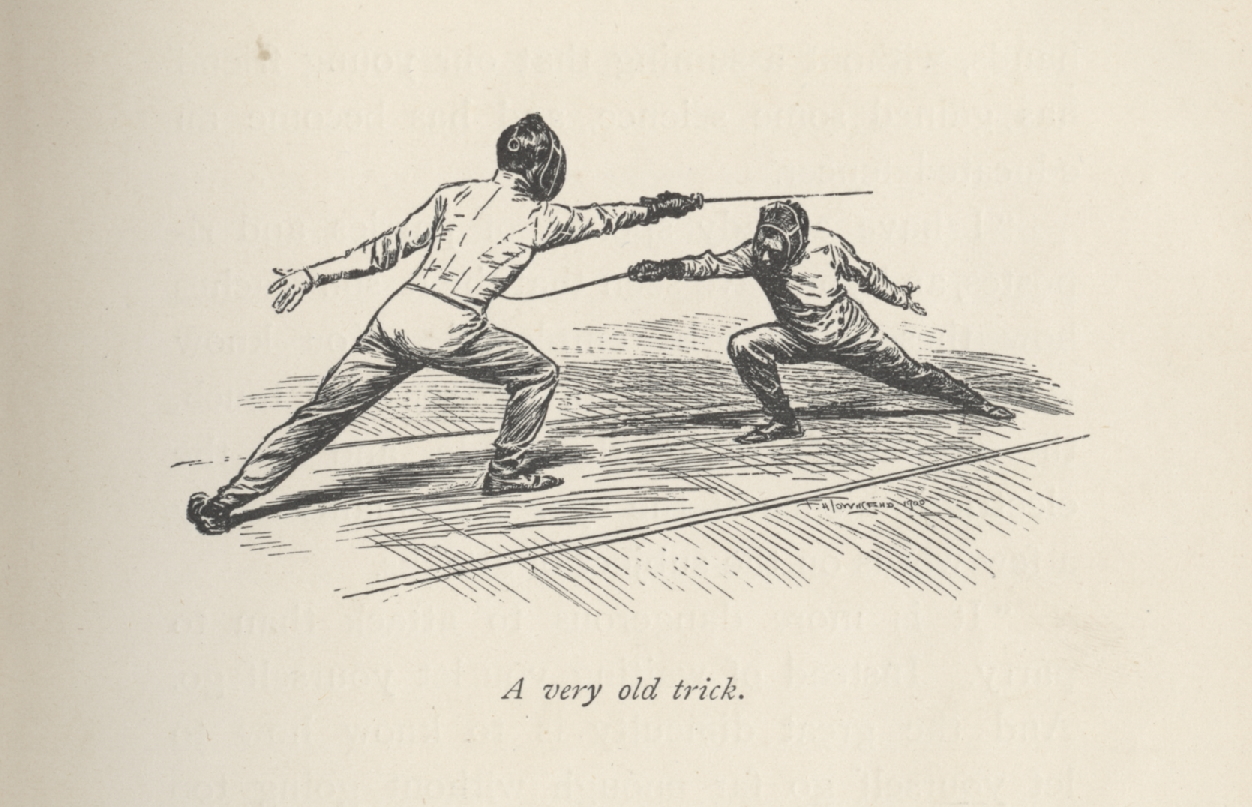

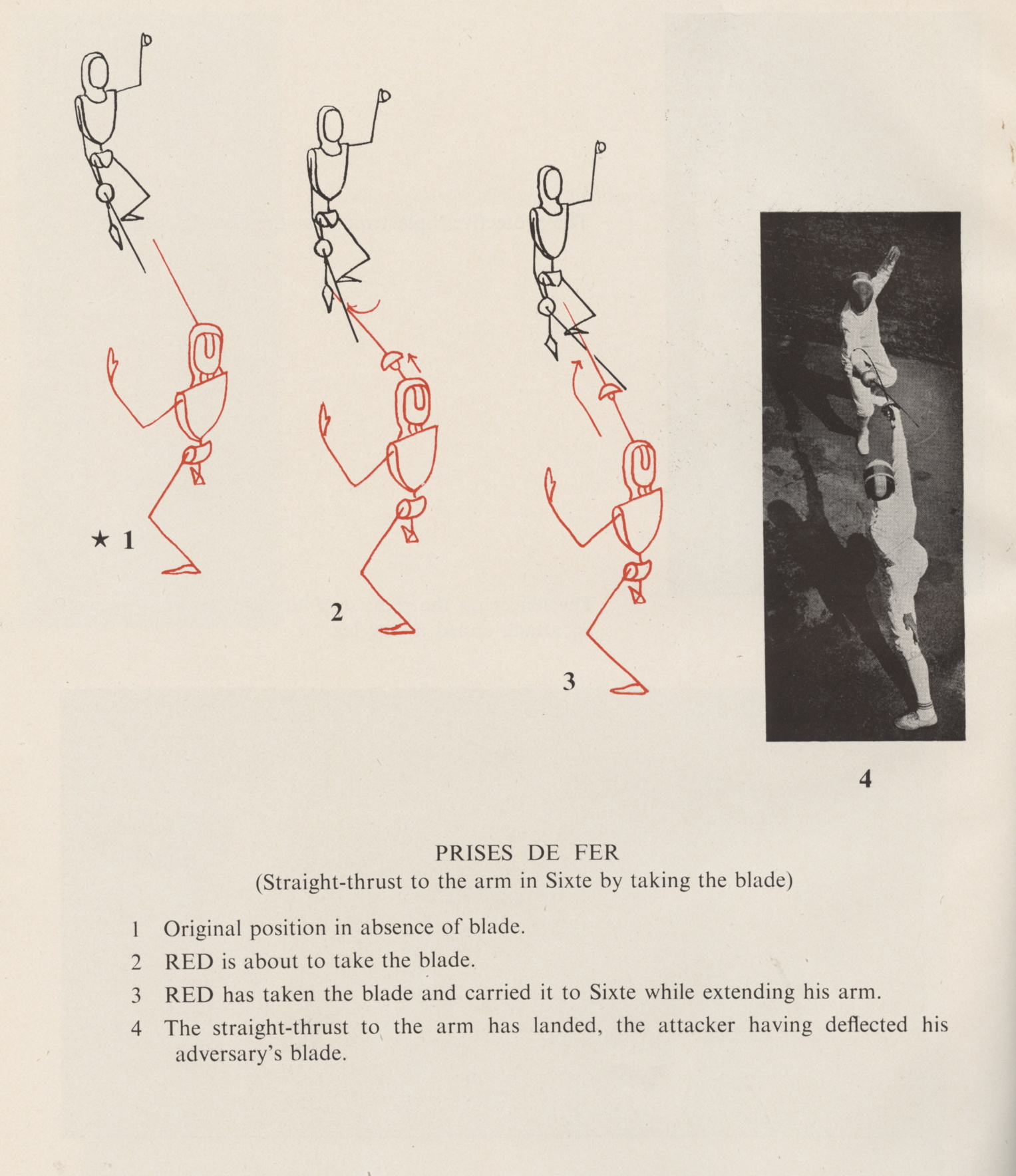

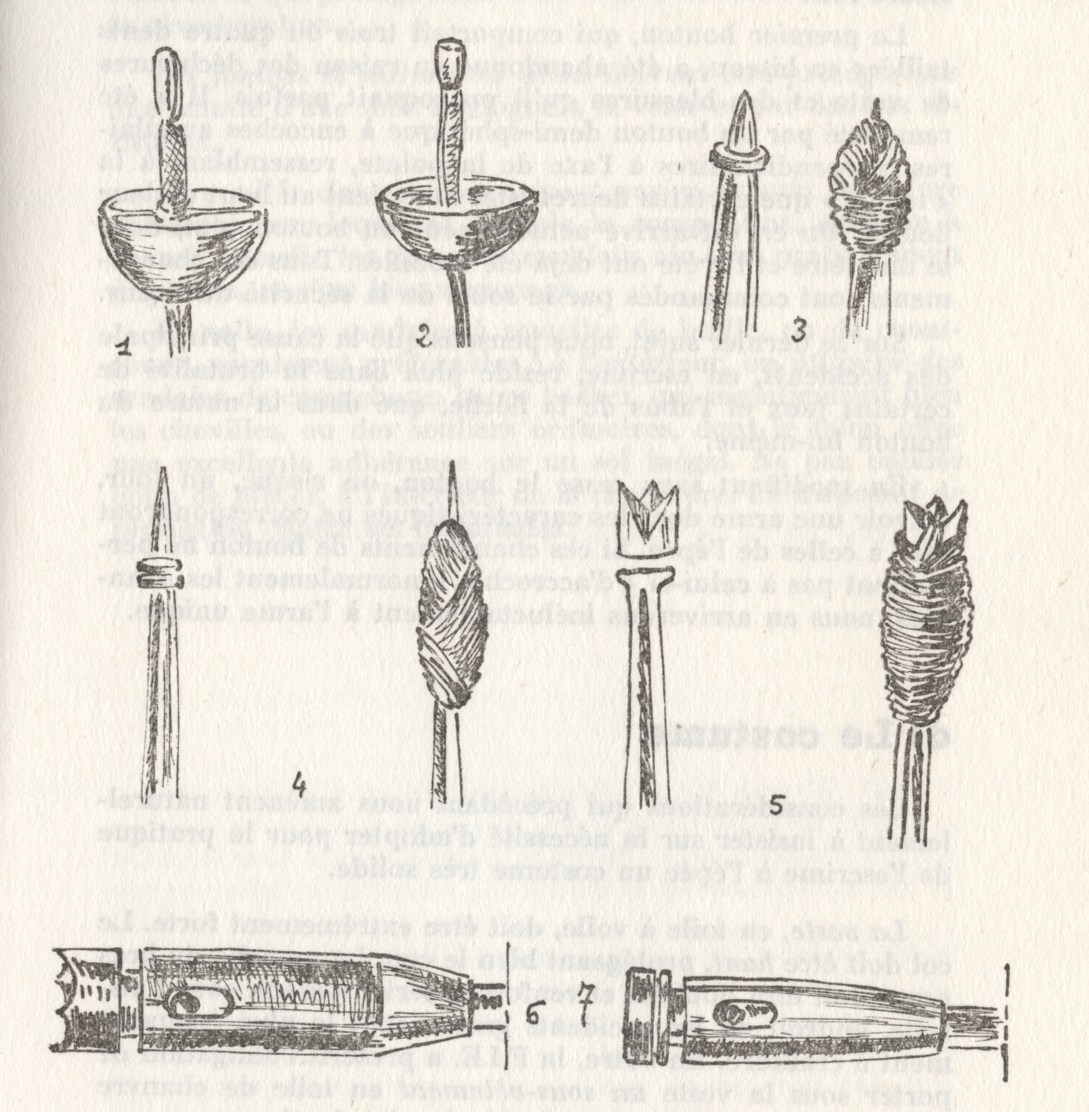

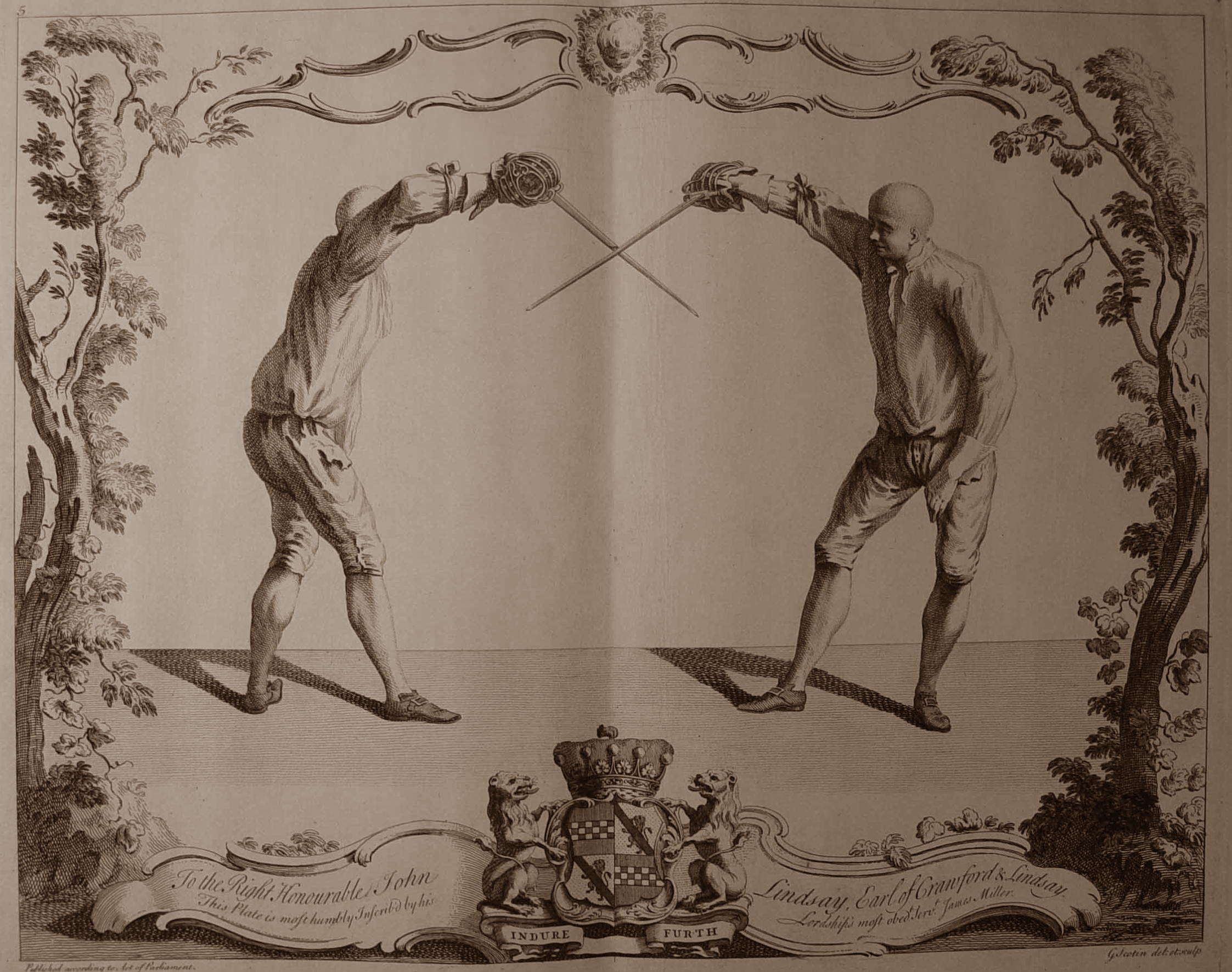

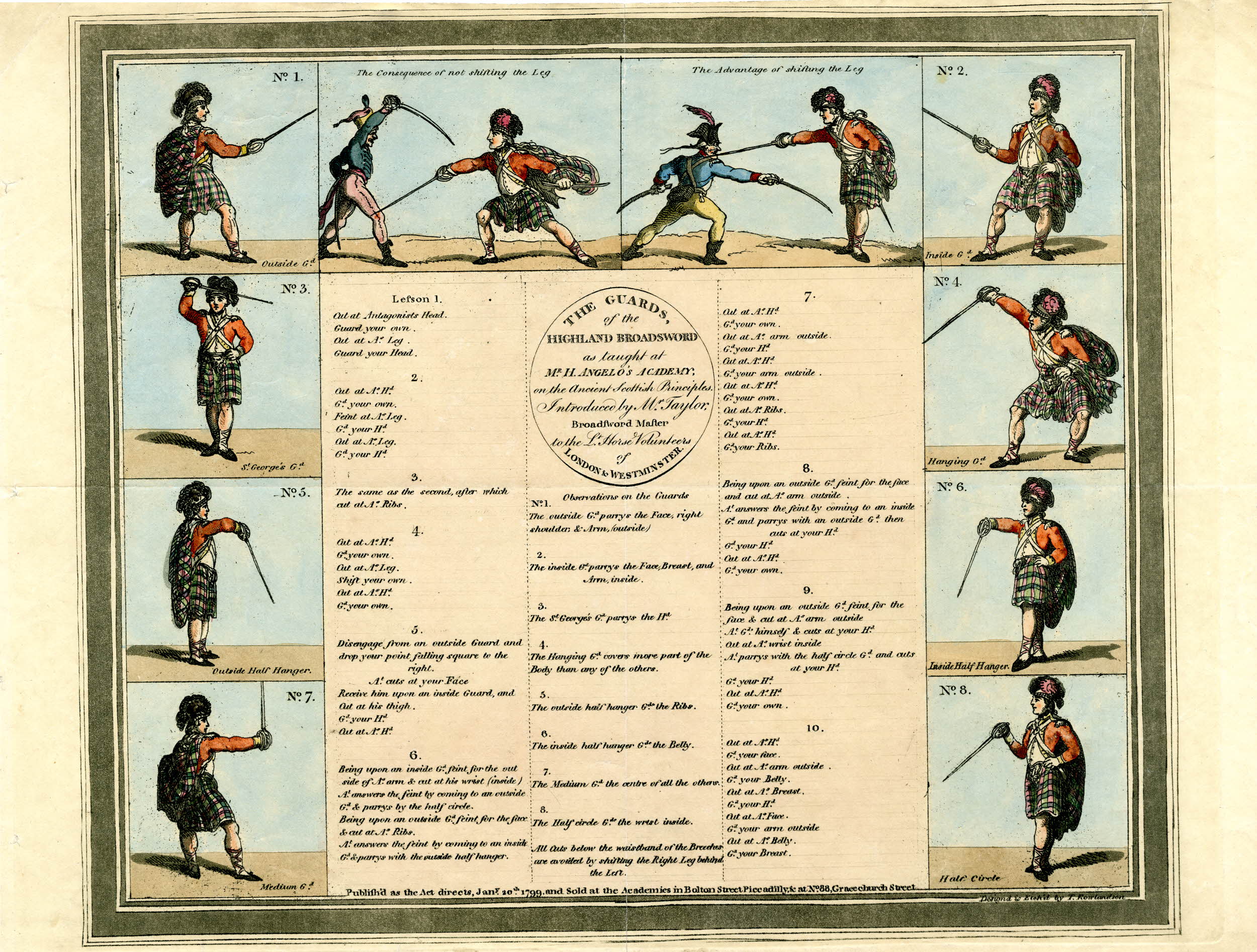

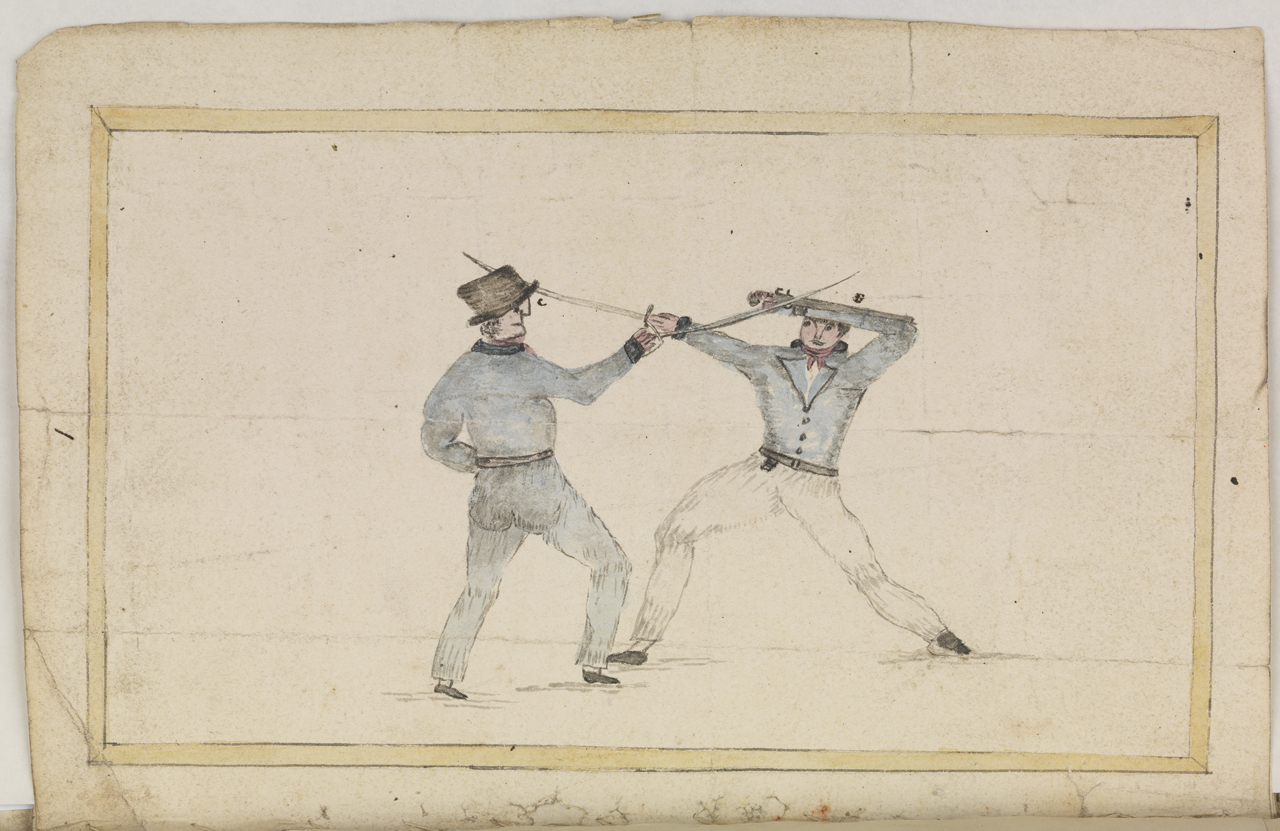

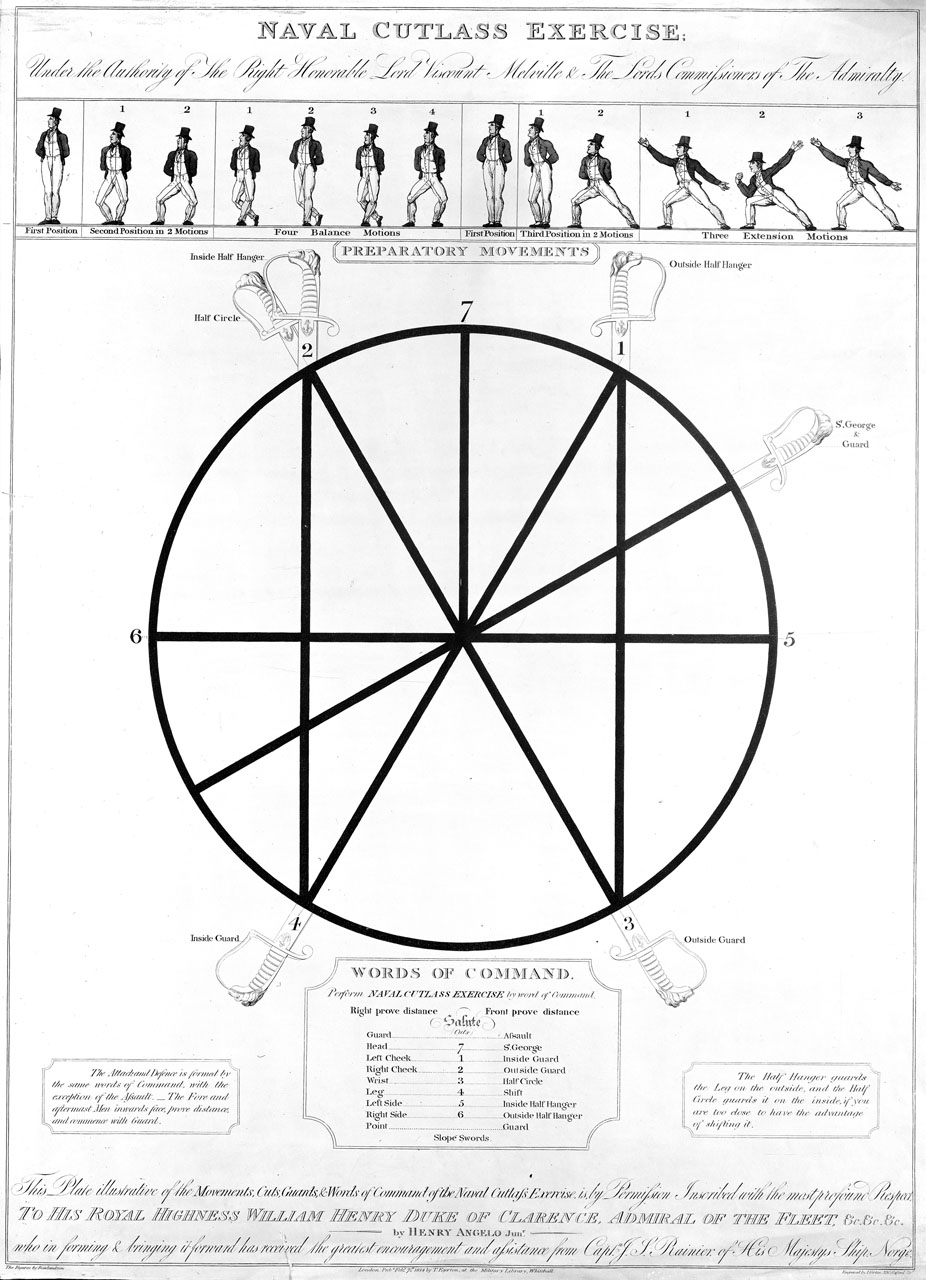

In general they consist of a lowering of the body to a lesser degree, often with a parry or beat first, or with a thrust in opposition. Below are a series of images depicting this in various forms over time.

The Passata Soto in Film

The passata soto is seldom shown in film, unfortunately, but here are four associated examples:

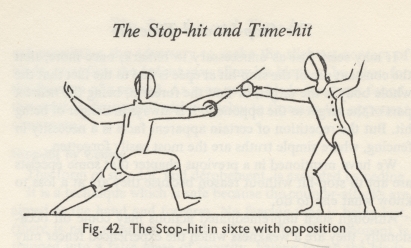

The Passato Soto in Modern Fencing

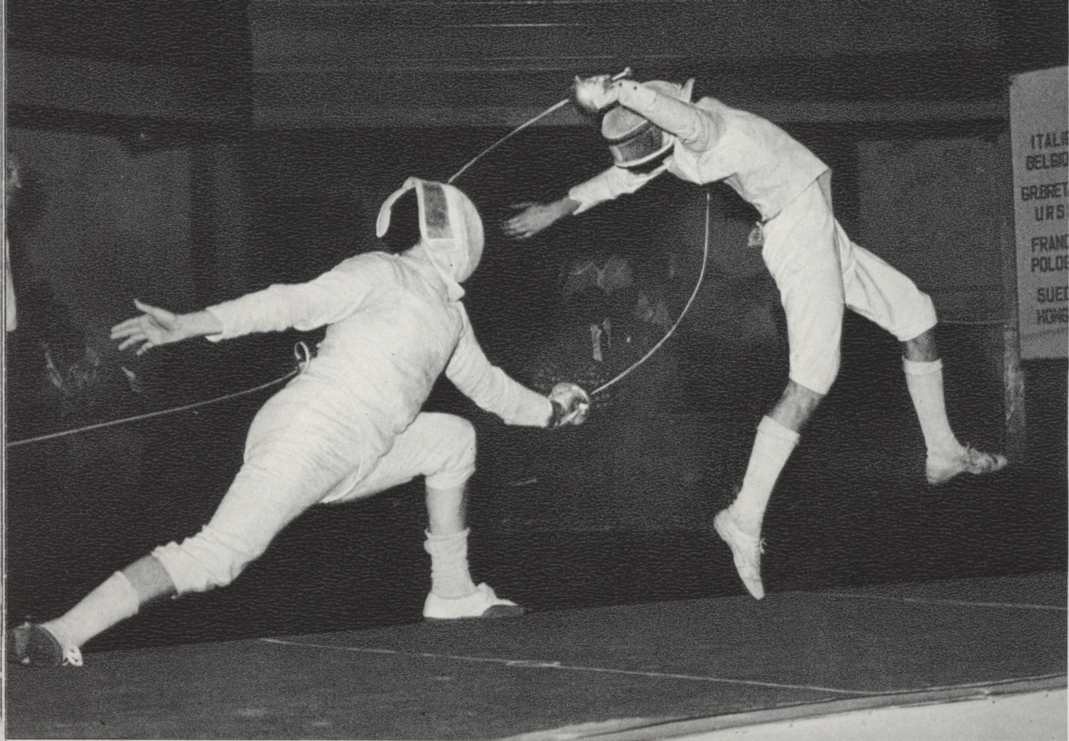

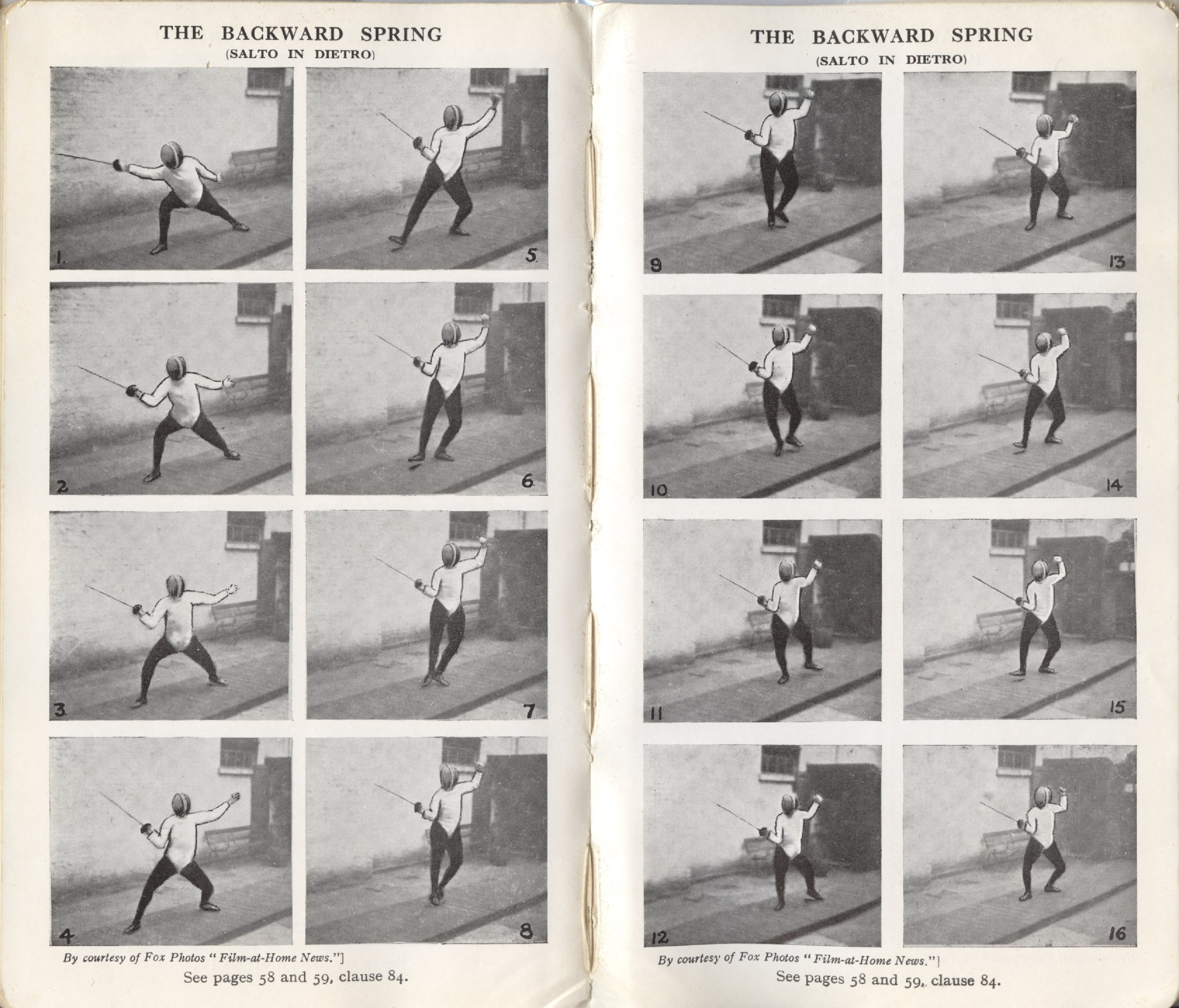

In modern competitive fencing, the technique is still occasionally seen in its classical form, in particular against a flèche, but more often is seen in the modified form of “squatting.” This is not a new technique! It was noted by Jean Joseph-Renaud more than a century ago. He correctly–as expected–notes that the latter form is easier.

In the spring of 1978 I saw it well-used by a University of Southern California epeeist–I made up the weakest third of the USC epee team, having fenced for less than a year–at a large collegiate meet at the University of California San Diego. The score was la belle (4-4), with no time limit for the final touch as I recall. (It was a nice rule that, of no time limit for the last touch! It’s long since been sadly abolished in the name of expediency…)

Suddenly both fencers stopped and pulled off their masks, but for no reason other than that they had heard the bell on the adjacent strip and, their adrenalin up for the la belle touch, mistook it for theirs. The young director… Hold on for a moment. Today the director, from directeur de combat, the person who “directs” a duel, is called a “referee,” solely because the foolish powers that be thought it would make fencing more spectator friendly… Seriously.

But back to our anecdote. The young college-age director, rather than enforcing the halt and putting the fencers back on guard, said “I didn’t call halt!”

You know what surely happened next. Without putting masks back on, immediately the opposing team’s fencer flèched while ours dropped into a beautiful passata soto. We got the touch and the bout. Neither fencer, thankfully, was hit in the unprotected face. Or at least that’s how I recall it happened.

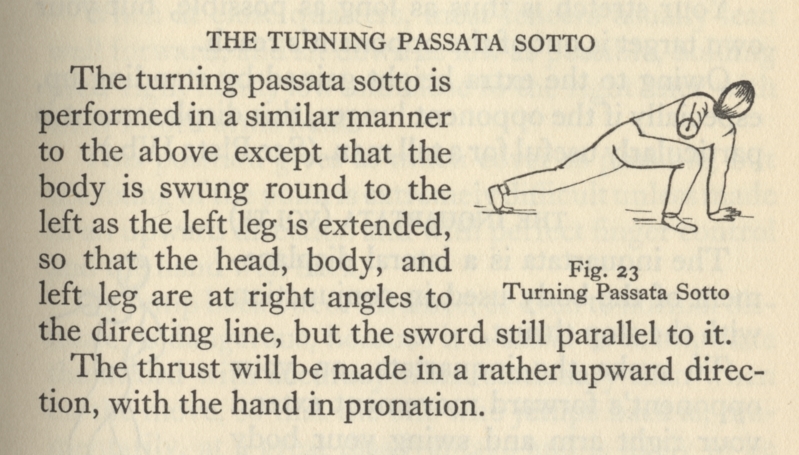

In modern usage, although infrequently seen, is a form known as the “turning” passata soto. The description is best left to R. A. Lidstone:

In competitive use, the modern form most often takes the form of ducking or squatting, shown below. Ducking has been used for at least seventy-five years in modern fencing.

Copyright Benerson Little 2017-2023. Last updated October 24, 2023.

Did Pirates Wear Eye Patches?

Costume illustration of an eye-patched, peg-legged seaman by Paul Gavarni for the Carnival in Paris. The popular image–trope, if you prefer–of the disabled seaman had been in place for more than a half a century by now, if not longer, in both Britain and France. This image was created between 1838 and 1843. British Museum.

So, “Did pirates wear eye patches?”

The short answer: Only if they had lost eyes to disease or injury, and this was no more prevalent among pirates than among fighting seamen and soldiers. In other words, the eye patch is in no way a sign or symbol of the pirate per se, nor even of the seaman in general.

Still, the question is a good one, if only to give us a reason to dig into related history.

The Mythbusters television show and other speculators have recently added to the myth by working backward from the proposition, that is, “If pirates wore eye patches, why would they have worn them?” rather than looking first at primary sources to see if there is any evidence that pirates wore them at all. There isn’t, other than as noted below.

The associated suggestions that pirates may have worn eye patches to improve night vision or daylight lookout observations or to enable them to fight below decks isn’t supported by any primary source material. In fact, the loss of sight in an eye, even by wearing an eye patch, causes significant loss in both depth perception and visual breadth, making movement aboard a vessel, aloft especially, very dangerous. It would also make visual observation by a lookout much more difficult.

As for fighting below decks, pirates and other seamen didn’t really do much of it: it was much easier to flush crew below decks by tossing grenades and firepots into breaches chopped into decks and bulkheads with boarding axes. In other words, the mere idea that eye patches might have been used to aid in fighting below decks shows a clear lack of understanding of the subject.

In other words: There is no historical evidence at all for any of these purported reasons why a pirate might have worn eye patches! Mythbusters and other popular “documentaries” are entertainment, not serious history. This includes “The History Channel,” now known I think as History.com: it’s “docu-tainment,” not real history. Trust me on this: if you’re being interviewed as an expert for a TV “documentary” and produce too many facts against the episode’s premise, the producers won’t put you on screen!

Again, let me emphasize: if a pirate wore an eye patch it was because he had lost an eye or was disfigured in his eye, and for no other reason!

The origin of the modern myth that pirates wore eye patches is largely literary. However, its roots lay deep in reality, both in the fact that eyes were often lost to disease and battle trauma, and that a one-eyed person often looks fearsome or sinister. The latter sense goes back millennia, and probably farther. Homer’s Cyclops, Polyphemus, is an early instance.

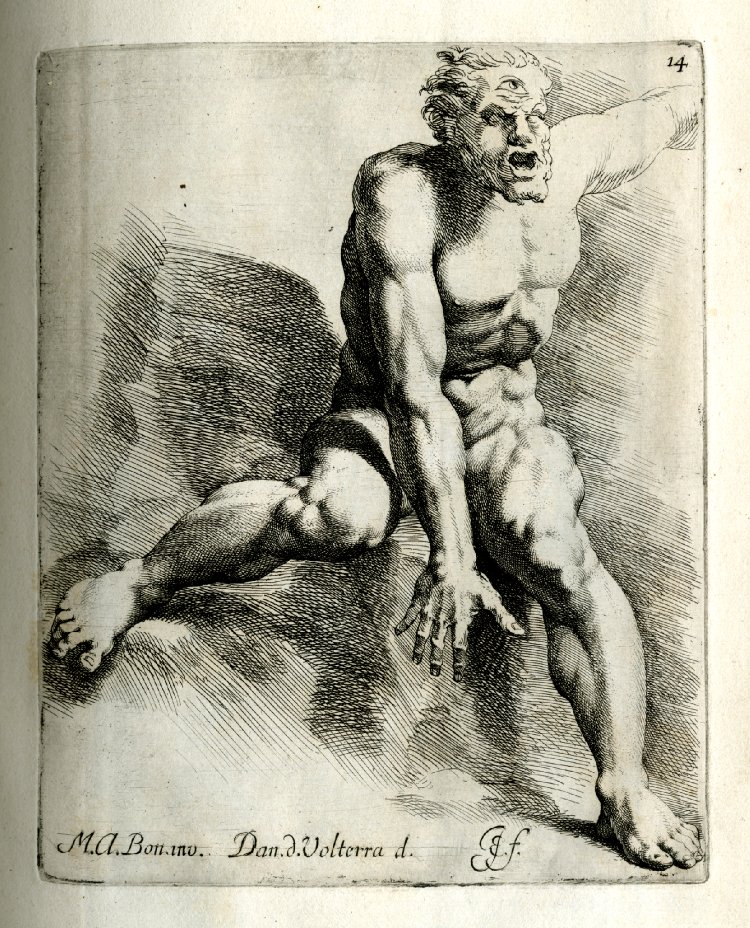

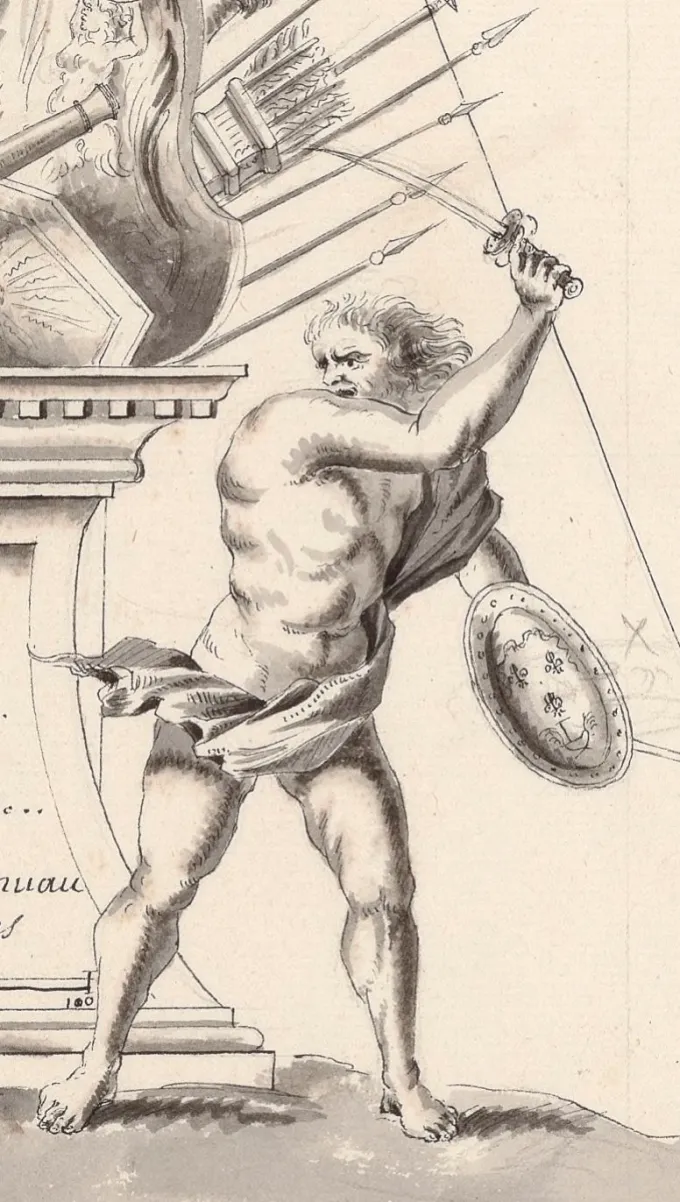

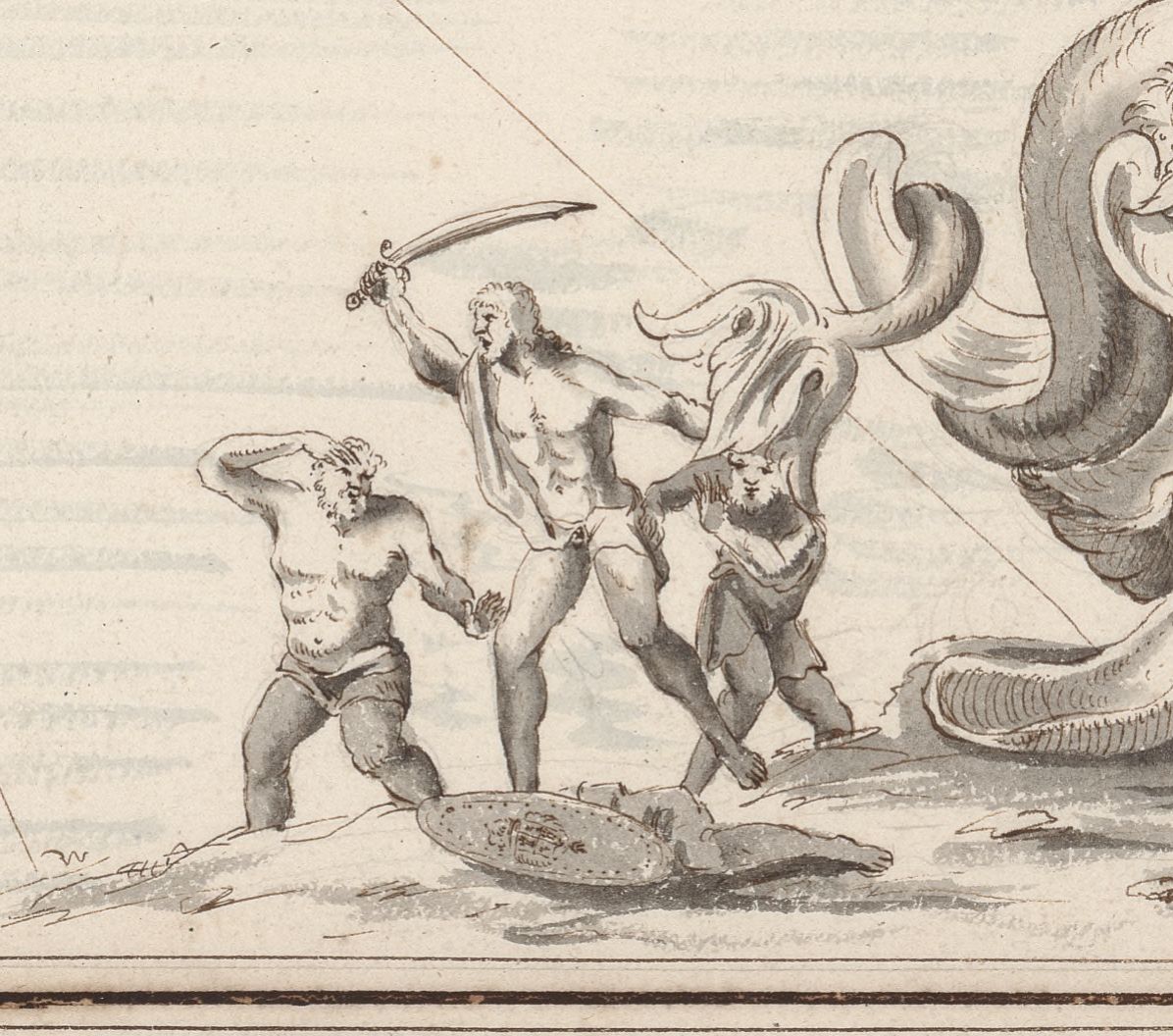

Polyphemus by Jan de Bisschop, after Daniele da Volterra, after Michelangelo, after Pellegrino Tibaldi, 1671. Odysseus, aka Ulysses by the Romans, blinded him. British Museum.

Some versions of Bernal Diaz’s The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico describe the fierce old musketeer Heredia, sent to frighten Native Americans, as a one-eyed, one-legged (or game-legged) soldier. The same work describes how Cortez’s enemy, Narvaez, lost an eye in battle.

A British army pensioner with eye patch and wooden leg. Again, the image was not restricted to naval seamen, much less, and popularly, pirates. By Isaac Robert Cruikshank, late eighteenth or early to mid-nineteenth century. British Museum.

Among seafaring journals and other records of the Golden Age of Piracy, there is only occasional mention of one-eyed seamen, usually in lists of those wounded in battle. Exquemelin’s various editions of The Buccaneers of America famously list compensation for the wounded, including the loss of an eye, and it is here that the primary source of the myth of pirates and eye patches is probably to be found, in combination with other works such as Bernal Diaz’s. The loss of an eye in battle was fairly common, in fact: seafarer Edward Coxere describes the use of oakum and tallow to stuff an eye socket in order to heal the wound, for example. Notably, none of the several eyewitness images of buccaneers or flibustiers from the 1680s show any with any of the usual Hollywood characteristics: wooden legs, eye patches, parrots, hooks, &c. This is to be expected. The large number of images of seamen, usually naval, with eye patches dates to a century later.

Images of splinters produced by round shot during an accurate test of the damage done in action. Author’s photos taken at the Erie Maritime Museum.

As a friend, “Tweeds Blues,” pointed out recently, it seemingly would not be surprising to find a fair number of one-eyed naval, privateer, and pirate seamen, given the damage done by splinters in action. Here I feel the need to point out yet again that Mythbusters is entertainment: one episode even suggested that splinters didn’t cause much damage in a naval action. In fact they did: there are hundreds, if not thousands, of accounts of the damage done, not to mention at least one accurate test that proves the horrible extent of damage splinters can do. The Mythbusters test parameters were simply incorrect, not to mention that overwhelming historical evidence was largely ignored, as were previous–and more accurate, historically correct–tests. The images above show splinters resulting from round shot striking a correctly-built hull section. The test was conducted by the Maritime Museum in Erie, Pennsylvania, home of the Flagship Niagara.

Admiral Don Blas de Lezo y Olavarrieta. Blas de Lezo is best-known for successfully defending Cartagena de Indias against British attack in 1741. Injuries received during his naval career included the loss of an eye, his left hand, his left leg below the knee, and the laming of his right arm. Museo Naval, Madrid.

Joseph Burgin, a Greenwich pensioner, who lost and eye and a leg in action in the Royal Navy in the early eighteenth century. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Of course, the most famous example of a naval mariner with an eye patch is arguably, at least in the UK and probably the US, that of Lord Admiral Horatio Nelson, who lost the sight in one eye during the capture of Calvi on Corsica in 1793–except that did not actually wear an eye patch. This has not stopped the popular assumption that he did from becoming prevalent, and, although out of our period, this has still influenced the idea of the one-eyed mariner, and therefore one-eyed pirate. Admiral Nelson also lost an arm. Some would argue, at least in the Hispanic world, that Bras de Lezo (second image above) is the most famous eye-patched admiral.

“Portret van Johann Karl von Thüngen,” the German field marshal. Period images of him show this eye patch worn without a thong, string, or other tie. Anonymous, 1675 – 1711. Rijksmuseum.

The fact is, patches were commonly used to cover any facial disfigurement. In the seventeenth century diarist and navy secretary Samuel Pepys wore a black patch, or possibly a large beauty patch, to cover a large cold sore. Similarly, King William III advised a soldier to remove the black patch covering the scar on his face because “It’s more honourable in a Soldier to wear a Scar than a Patch.” (For the latter reference, see Coke in the sources listed below.)

Scottish soldier Sir William Brog, 1635, with a patch covering a scar on his nose. (And an earring too.) Pring by Crispijn van Queborn. British Museum.

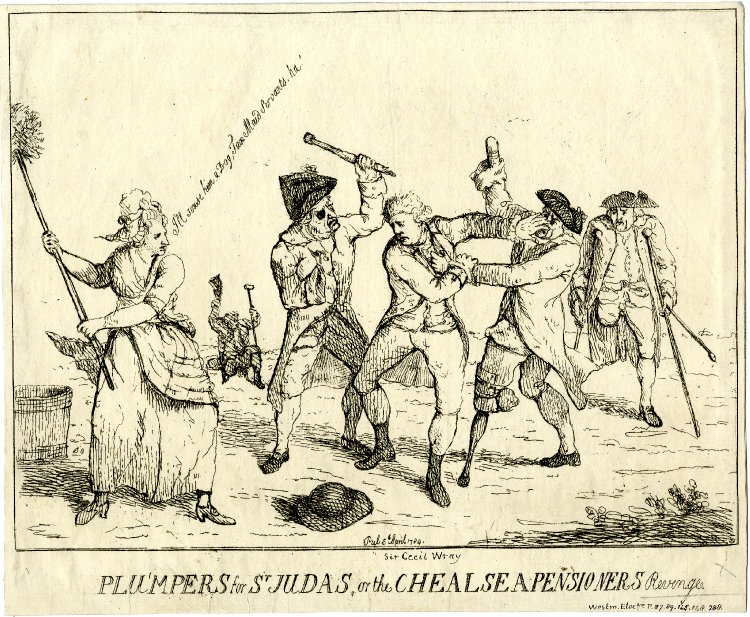

Eye patches, stumps aloft and ‘alow, not to mention peg legs. “Plumpers for Sr Judas, or the Chealsea Pensioners Revenge,” a satirical print, 1784. British Museum.

By the late eighteenth century the image of the eye-patched, peg-legged seaman was iconic, probably the result of the increased number of British naval actions brought on by the American Revolution and, especially, the Napoleonic Wars. Notably, in reality most such disabled seamen were pensioned from service, as shown above. These satirical images are probably the material origin of the popular identification of the naval seaman, and therefore the pirate, with eye patches.

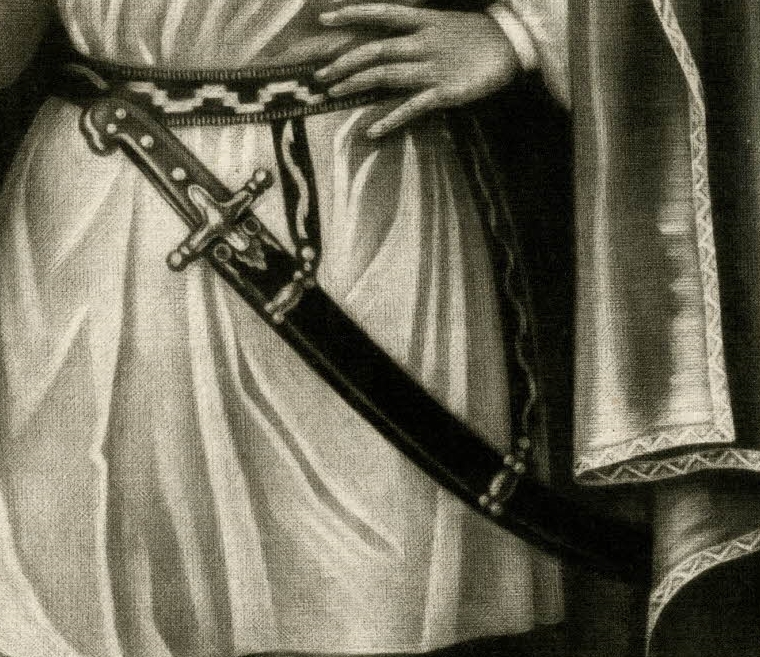

Even with its legitimate historical roots in fact, this pirate myth, like many, didn’t come fully into being until the mid-nineteenth century, a hundred or more years after the Golden Age of Piracy. Sir Walter Scott in The Fortunes of Nigel describes “The noble Captain Colepepper, or Peppercull, for he was known by both these names, and some others besides, had a martial and a swashing exterior, which, on the present occasion, was rendered yet more peculiar, by a patch covering his left eye and a part of the cheek. The sleeves of his thickset velvet jerkin were polished and shone with grease, — his buff gloves had huge tops, which reached almost to the elbow; his sword-belt of the same materials extended its breadth from his haunchbone to his small ribs, and supported on the one side his large black-hilted back-sword, on the other a dagger of like proportions.” Here is the epitome of the swashbuckler, easily translated to the pirate.

The bold and swaggering Captain Colepepper, from The Fortunes of Nigel by Sir Walter Scott. Nineteenth century, unknown edition.

Not long after, Charles Dickens described a pirate with “the one eye and the patch across the nose” and soon afterward similarly did many writers of popular fiction. However, many of our principle originators or propagators of pirate myths—Robert Louis Stevenson, J. M. Barrie, N. C. Wyeth, for example—do not appear to have bothered with this myth, although Barrie’s Captain Hook probably did encourage other images of pirates missing a vital part such as a limb or eye, and Howard Pyle in The Ruby of Kishmoor equips a pirate, one of the four in the short tale, with an eye patch.

In 1926 Douglas Fairbanks propagated nineteenth century pirate myths, as well as a few he helped create, across the world with his film The Black Pirate. In it he established the modern pirate swashbuckler stereotype, based much on Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates, Peter Pan, and probably Captain Blood (one of whose characters, by the way, was one-eyed, although he lost the eye at Sedgemoor, not at sea). Around the same time, we begin to see pirate book cover art and other illustrations showing pirates with eye patches. But it would take later films, such as The Black Swan and The Crimson Pirate to make the eye patch an obvious, routine part of the stereotypical pirate costume.

Publicity still from The Black Swan, 1942. An eye-patched Anthony Quinn is on the right.

Sources

Roger Coke. A Detection of the Court and State of England. 4th ed. London: J. Brotherton and W. Meadows, 1719. Vol. 2:472.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España. Reprint, Madrid: Don Benito Cano, 1795. See vol. 1:213.

Edward Coxere. Adventures by Sea of Edward Coxere. Edited by E. H. W. Meyerstein. London: Oxford University, 1946.

Charles Dickens. “The Perils of Certain English Prisoners.” 1857. Reprinted in Charles Dickens’s Stories from the Christmas Numbers. New York: MacMillan, 1896. Page 144.

Alexandre Exquemelin [John Esquemeling]. The Buccaneers of America. London: Crooke, 1684. Reprint, New York: Dorset Press, 1987. Page 60.

Benerson Little. The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016. Prologue.

——. “El Mito Pirata” in Desperta Ferro 17 (August 2015), 52-55.

Heidi Mitchell. “Does Reading in Dim Light Hurt Your Eyes?” Wall Street Journal online, April 8, 2013, http://www.wsj.com.

Mythbusters, Episode 71.

Samuel Pepys. Diary. September 26, 1664.

Walter Scott. The Fortunes of Nigel. Boston: Samuel H. Parker, 1822. Page 255.

The Telegraph. “Nelson didn’t wear eye-patch, says historian.” January 19, 2005.

Copyright Benerson Little, 2017. Last updated August 14, 2025.

Pirates & Earrings

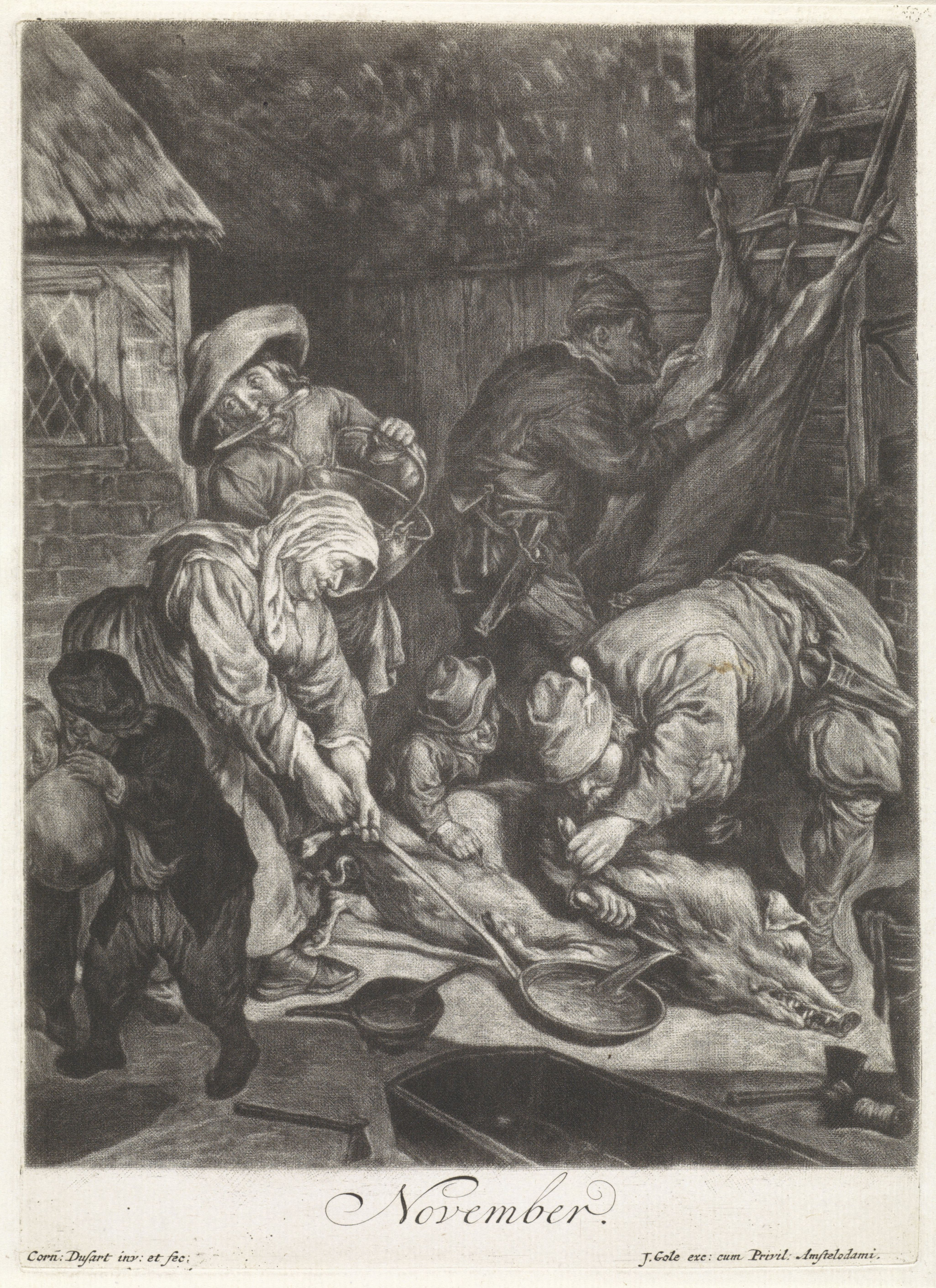

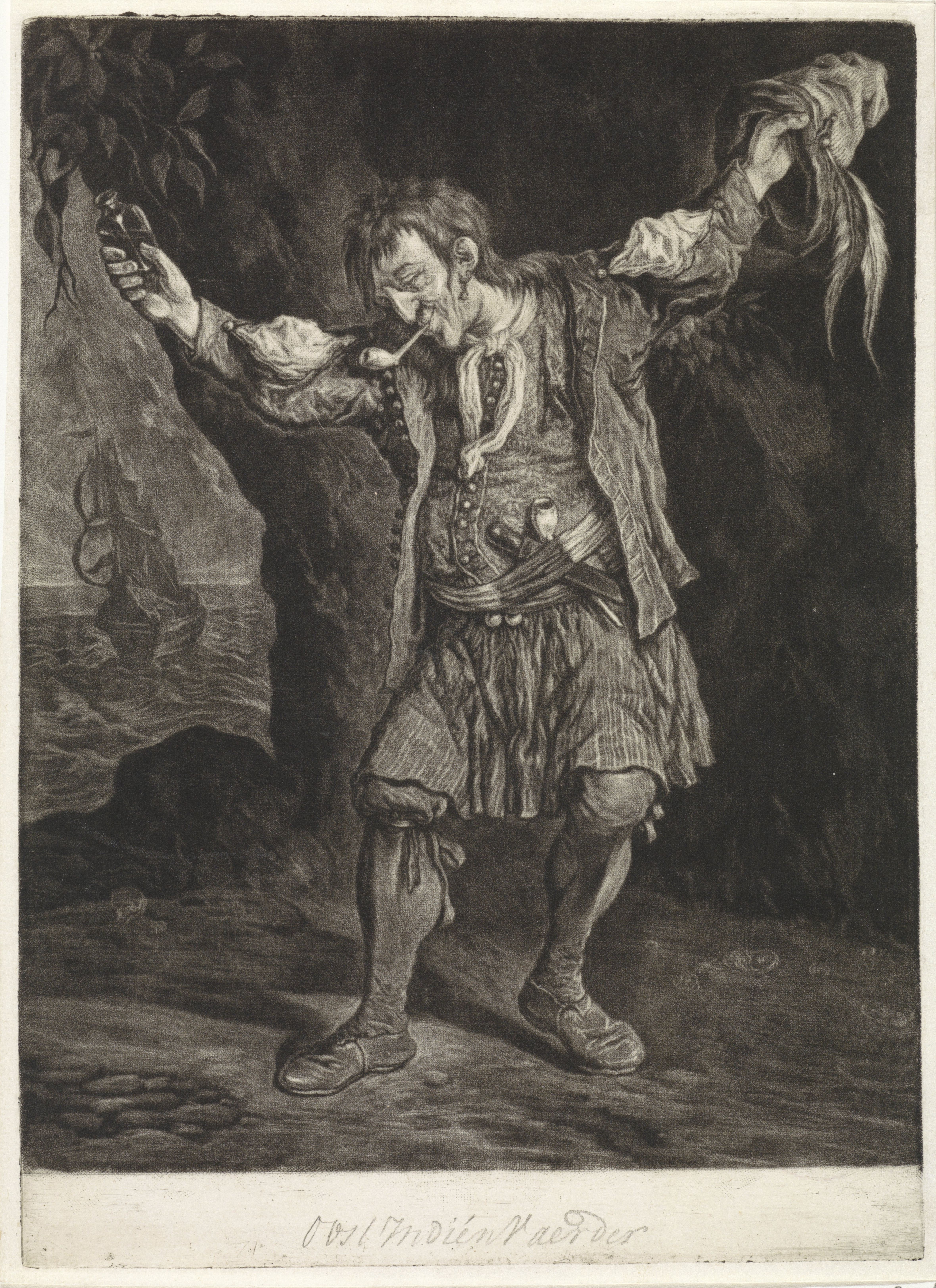

A Dutch seaman in Amsterdam dancing in celebration of the recapture of the city of Namur in September 1695. By Cornelis Dufart, 1695. Rijksmuseum.

Quite often today, reenactors, students of authentic pirate portrayals of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, aka the “Golden Age of Piracy,” and the makers of any television documentary or drama, or any film, about pirates who wants to be taken seriously will generally drop the pirate earrings and other pirate caricature, or at least minimize them. However, this practice, while avoiding “Hollywood” cliché, has one problem:

There were “Golden Age” seafarers who wore earrings.

The same goes for pirates of the “Golden Age” from circa 1655 to 1730.

As is the case with much of our perception of what is and is not correct and authentic about “pirates,” the myth or reality really applies much more broadly, to seafarers in general, and from there to the question of whether the myth or reality applies across the board to seafarers or only to a specific subset. For example, I was asked during a Reddit AMA a while back about the “crossing the line” ceremony originating from pirates. It doesn’t actually originate with sea thieves, but from mariners in general, unless all mariners were sea thieves. (Of course, some might argue that at least through the Middle Ages all seafarers were potential pirates…) Sea rovers may have practiced the various “crossing the line” ceremonies, just as seamen in general did, but it was foremost a maritime practice, not one specific to piracy. And I say various practices because there were different cultural practices, and different “lines” to cross as well.

So, put simply, were earrings a conventional part of pirate dress, or of maritime dress, in general during the period 1655 to 1730?

I’m going to keep the answer just as simple, for this is not the place to address the variety of seafarers, sea thieves, and their national and local customs and dress.

And the simple answer to both is…no.

Even so, many answers are really not so simple as they seem, and so it is with this one. There are three exceptions to the earring rule, and they apply not only to pirates and privateers, but to mariners in general.

“Matelot de Brabant / Brabantsche Schipper” by Bernard Picart, circa 1690 to circa 1733. Note the single pearl in the earring, apparently common among Dutch seamen. Rijksmuseum.

First is the Dutch exception. Earrings were common in the mid to late seventeenth century and into the eighteenth on many Dutch seafarers, as is clear by the several images I’ve posted here. The seaman in the image above wears an earring in the left ear, and the seamen in the Dufart images below mirror each other, one in the left, the other in the right. From the images it’s impossible to tell if the Dutchmen are wearing an earring on the other ear as well.

An earring or a wisp of hair? Dutch or possibly Norwegian seaman, late seventeenth century. Pas-keart van de Cust van Noorwegan by Joannes van Keulen.

So, if you want to be a sea rover and wear an earring and be historically accurate, be a Dutch pirate or privateer. That said, many serious pirate and privateer reenactors are opposed even to this out of concern that it gives the wrong impression: either in general, or because most of the early eighteenth century pirates were “Anglo-American,” or because there are only a “few” Dutch images of seafarers with earrings (although a “few” images would well suffice to support “facts” such reenactors are in favor of). For me, fact–truth–should outweigh this. First, given the large number of buccaneers or flibustiers of Dutch origin in the late seventeenth century, it would not be surprising to find earrings on some buccaneers. Second, not all of the early eighteenth century “Anglo-American” pirates were in fact British or Irish derived, and separate from them were French and Spanish pirates whose crews doubtless included some Dutch members.

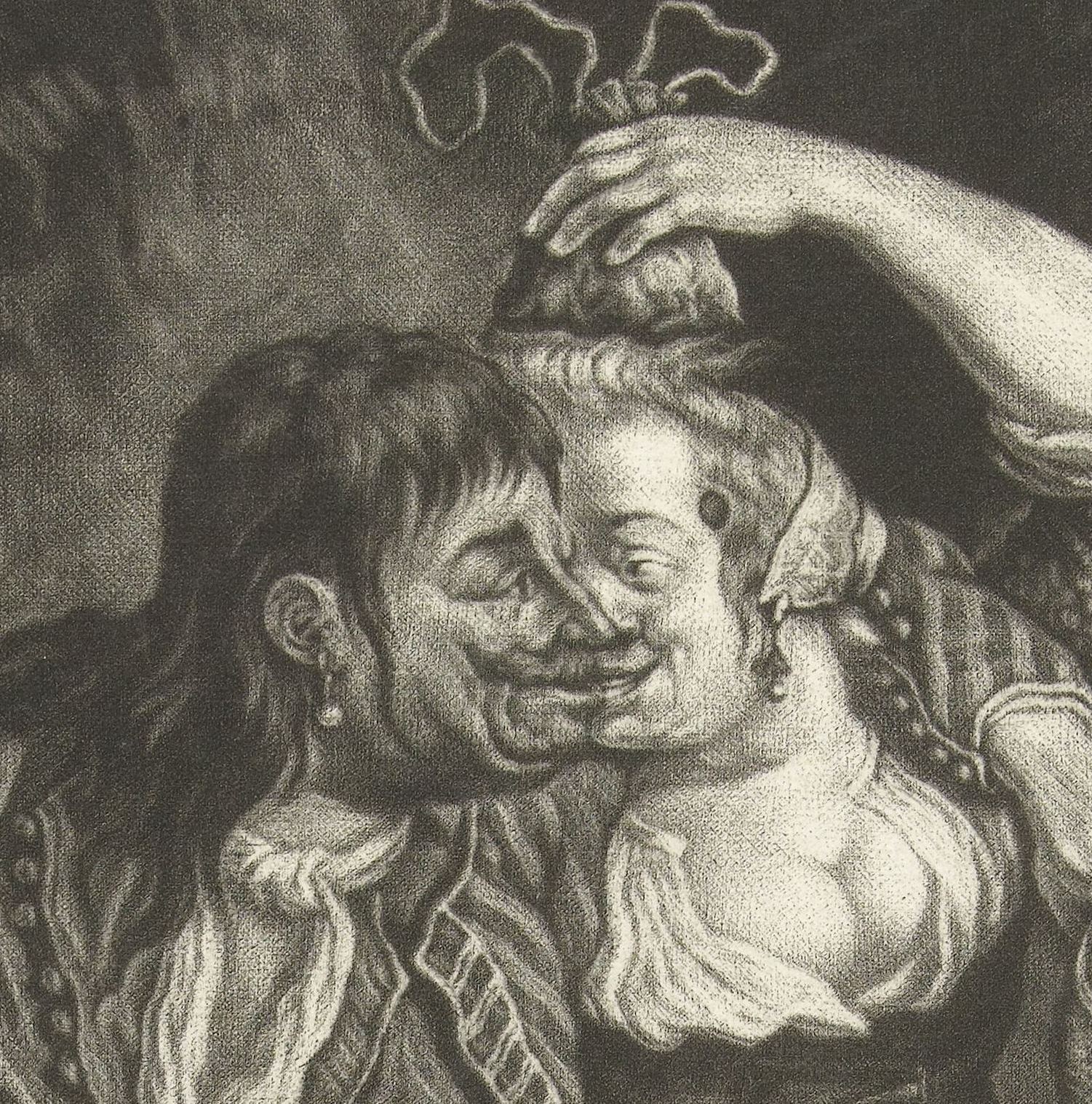

Detail of a Dutch seaman in Amsterdam dancing with a woman in celebration of the recapture of the city of Namur in September 1695. By Cornelis Dufart, 1695. Rijksmuseum.

Dutch seaman with a rummer (Dutch roemer, a large drinking glass). Note the obvious earring. Jacob Gole, after Cornelis Dusart, after a fairly similar illustration lacking knife, pipe, and earring by Abraham Bloteling, 1670 – 1724. Using other artist’s and engraver’s illustrations as templates was common. Rijksmuseum.

Second is the fop exception. Through much of the seventeenth century, including the last quarter, and into the eighteenth century some French fops, and some English onesas well for they generally followed French fashion, were in the habit of wearing an earring, perhaps even one in each ear. The common assumption is that men’s earrings in England and Scotland went out of fashion after the death of Charles I, but this is not entirely the case. They became less popular, and were restricted largely to the foppish gentleman and would-be gentleman–a more restricted group of “gallants” than in the first half of the century.

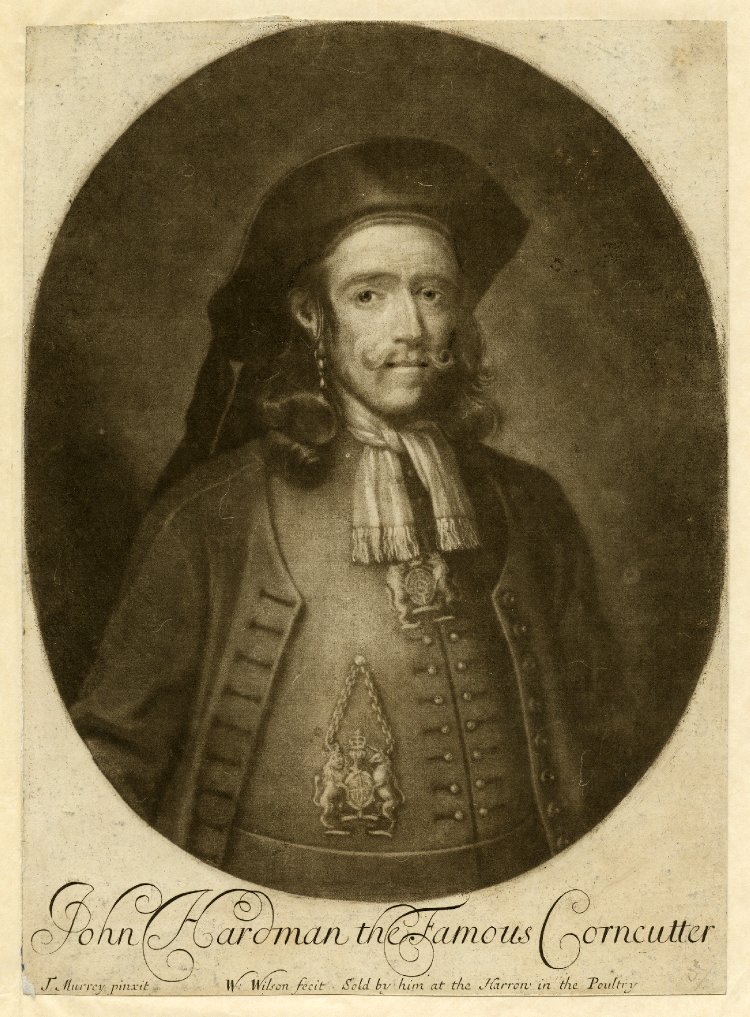

“John Hardman the Famous Corncutter.” Hardman was a specialist in corns and bunions, and it is speculated, given the royal device hanging from his waistcoat, that he may have worked on King William III’s feet. Little is known about Hardman, and at least one early nineteenth century writer suggests he was Dutch given the English royal arms he is wearing (the author notes the large number of Dutchmen in London during the reign of William III), but possibly due in part as well to his mustache and earrings, and quite possibly because the author did not want to recognize an Englishman as a possible mountebank. Even so, it remains possible that Hardman was merely a flamboyant Englishman. Although the name’s roots are Germanic, it was and is a fairly common English surname. Note the long earring. British Museum.

References to earrings on men in the second half of the seventeenth century include a letter written by George Fox (of the Society of Friends, or Quakers) in 1654, but not published, I don’t believe, prior to the 1690s: “a company of them playing at bowls, or at tables, or at shuffle-board; or each taking his horse, that hath bunches of ribbons on his head, as the rider hath on his own (who, perhaps, hath a ring in his ear too)…” This isn’t too long after the execution of Charles I, when we might still see earrings (and which many secondary texts say is about the last time Englishmen wore earrings), and is at the beginning of the Golden Age of Piracy, assuming a start date of 1655 with the capture of Jamaica.

Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt (1601-1666), known as “le Cadet la Perle” due to his bravery in battle. Earrings were quite common on military men in England, Scotland, and France in the first half of the seventeenth century, and on artists and others as well: a 1650 self-portrait of Rembrandt shows him wearing a pearl earring and a self-portrait of Ferdinand Bol shows him wearing a small gold hoop. Print by Nicolas de Larmessin, 1663. British Museum.

Goldsmith Louis Roupert, 1668. Print by Louis Cossin based on a painting by Pierre Rabon. Rijksmuseum.

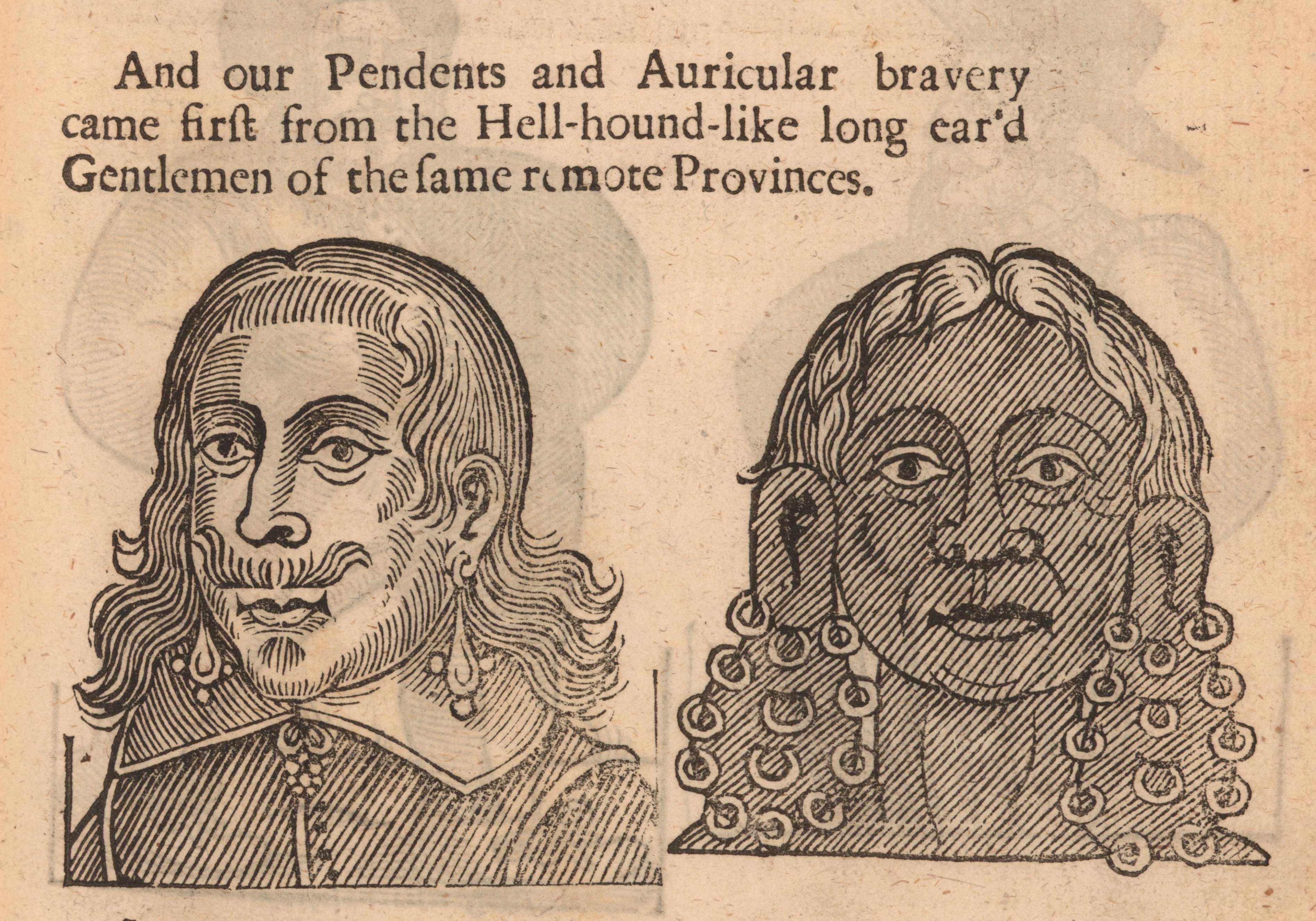

Similarly, note the illustration below. Published in 1653 as part of an appendix satirizing the English gallant and his ostentatious dress and body ornamentation, it does prove that even at this date some English gallants still wore not only one, but two earrings at times. The author, Dr. John Bulwer, compares earring-wearing and other ostentation to that of foreign savages and heathens, or even to pre-Christian Britons, and appears to approve only of plain sober dress, as one might expect during the Age of Cromwell–up with the cropped Roundheads, down with the long-haired Royalists! “Children of vanity” is Bulwer’s disparaging, if also accurate on occasion, term for those who excessively ornament themselves. He also mocks gallants for wearing patches, starched collars (yellowed in fact with starch), flowing locks, mustaches, and so on. He is no less sparing of women. Curiously, Dr. Bulwer’s portrait shows him with flowing locks, a mustache, and goatee.

Illustration from “An Appendix of the Pedigree of the English Gallant” in Anthropometamorphosis: Man Transform’d: Or, the Artificiall Changling by John Bulwer. London: William Hunt, 1653. Dr. Bulwer’s work Anthropometamorphosis, in which he details the great variety of body ornamentation worldwide, is extraordinarily detailed for the era, sophisticated even by modern standards, even if more than a little bit patronizing. Dr. Bulwer is perhaps best known for proposing a system of sign language for the deaf.

Moving on to William Wycherly and The Plain-Dealer (one of my favorite plays), with a reference to the jewel in the ear and gunpowder spot on the hand, circa 1673, in the middle of the age of buccaneers. Originally I had considered the possibility that this might refer to the sea captain and not the fop, but other instances (George Fox above, for example), plus a re-reading, plus the opinion of a professor emeritus of seventeenth century English literature, have persuaded me that fops wore earrings more often than we think (the professor thought so, by the way)—enough to be an obvious reference for the audience. We’ll deal with gunpowder spots in another blog soon.

Head now to The Works of Mr. Thomas Brown: Amusements Serious and Comical, a comical and satirical group of works published in 1700, and we have the following: “I had honestly, deserved a better Reward than a Patch-box, a Toothpicker, and a small Ear-ring amounted to, and therefore need not disquiet my self upon that Score.. Thus you fee, Madam…” The gentleman has received several useful implements (but not what he was seeking) from his inamorata: an ear picker to clean his ears, a patch box for patches (fops wore them), and a single earring. The last might be simply a love token, but to what end if it can’t be displayed–worn, that is?

That French fops wore them is uncontested. By way of a nautical example, in 1704 the comte de Forbin, a famous, and arguably quite pompous at times, commerce-raiding French naval captain refused passage to a French monk who had been authorized travel from Livorno, Italy to France aboard the French warship by Cardinal de Janson. The monk wore a single gold earring with a large pearl, and Forbin specifically notes his foppish airs, that is, that he acted like a “petit-maître“–a fop or dandy. There were at the time a fair number of priests and monks as addicted to trappings of the flesh as to world beyond, if not more. In any case, it didn’t help that the monk was “haughty and arrogant.” In fact, it was probably this behavior that set Forbin off. But the captain’s reply to the monk was that the cardinal’s order said nothing about giving passage to a monk wearing an earring and giving the airs of a fop–so get off my ship.

In sum, if you want to be a sea rover with an earring but don’t want to be Dutch you might considering being a bit of a fop. This isn’t so very far-fetched, for their are examples of pirates wearing jewelry in a fashion that might be considered foppish. Quoting from The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths, an overly fashionable pirate “might wear a ‘necklace of pearls of extraordinary size and inestimable price, with rubies of surpassing beauty’ as Captain Nicolas Van Horn did, or a gold chain with a ‘gold toothpicker hanging at it’ as Captain John James did (and many of his crew also wore gold chains), or a ‘gold chain round his neck, with a diamond cross hanging to it’ as Captain Bartholomew Roberts reportedly did.” (Citations to the quotations above can be found in the endnotes to The Golden Age of Piracy. The quotation is from the prologue.)

Even so, I do tend to agree a bit more with reenactors who object to this exception out of concern for the wrong impression. That said, I still would not be surprised to find a foppish pirate wearing an earring. Devotees of the early eighteenth century Anglo-American pirates will argue quite factually that most were seamen. This doesn’t alter the fact that there may have some foppish seamen–I’ve known some modern ones who’d fit this description, although they’re in the minority–and there were a few non-seamen as well who might fit the fop bill, including the dilettante pirate Stede Bonnet. In my experience, both in studying seamen of the past as well as having known and worked with many modern seamen–naval, commercial, tall ship–during my life, mariners as a group are not homogeneous even though they may express attributes common to their profession. In other words, they too have personalities and often express them through their clothing, hair, and other body ornamentation.

Detail from a late sixteenth century watercolor of a Timucuan casique of Florida, by John White. Note the large “earring” or ear piercing. Such ornamentation was common among Native Americans. British Museum.

The third exception is that of Native Americans, Africans, and mixed races. This should be an obvious exception, but the fact that it is so often overlooked strongly suggests an ethnocentric–that is, a “white-centric” or “Euro-centric”–bias in the view of piracy and of the maritime in general. A fair number of English, French, and Dutch pirates and privateers, although not the majority, were non-white. The majority of Spanish pirates and privateers originating in the Caribbean were non-white. Many of these seafarers of color, particularly those of full African and Native American blood, probably wore earrings in one form or another.

Painting by Mexican artist Miguel Cabrera, circa mid-eighteenth century. The man is wearing an earring. The wearing of earrings among blacks and many men of mixed races was also common in the seventeenth century as well.

An African with a sword, quite possibly a West African slave trader. Seventeenth century. Sotheby’s.

Dutch school, a Moor, possibly a West African slave trader, smoking a churchwarden pipe. Seventeenth century. Christie’s.

Many period descriptions and images of Native American males mention or show earrings. Africans, and those of African descent, in European and American context in the seventeenth century are often shown wearing earrings, typically a single one. A large number of seventeenth century Dutch paintings show black servants and slaves wearing earrings, as does a painting of black Moor in North Africa and as does one of a possible West Indian slave trader.

One final note:

Earrings were a fashion statement!

Seamen of this era, including sea rovers, did not wear them to improve eyesight, pay for a funeral, or for any other nonsensical reason, no matter how reasonable such myths may seem when un-examined or otherwise taken at face value. Unfortunately, in spite of the wealth of accurate information readily available on the Internet, it has paradoxically fostered, or perhaps enhanced is more accurate, an intellectual laziness and willingness to believe anything in print.

Dean Cornwell, “From the old fort Blood surveyed Don Miguel’s squadron…,” oil on canvas, 1930, for the magazine serial edition of Captain Blood Returns. Mort Künstler Collection.

So, digressing slightly in order to speak historically about a fictional character, would Capt. Peter Blood actually have worn a large pearl earring as Rafael Sabatini described he did in Captain Blood Returns (aka The Chronicles of Captain Blood in the UK)? Of course he would have, for he meets two criteria: he has had service in the Dutch navy under de Ruyter and is, almost, a fop in his style of dress!

Copyright Benerson Little 2017. First posted July 2017. Last updated July 9, 2019.

Piracy Defined Through the Ages

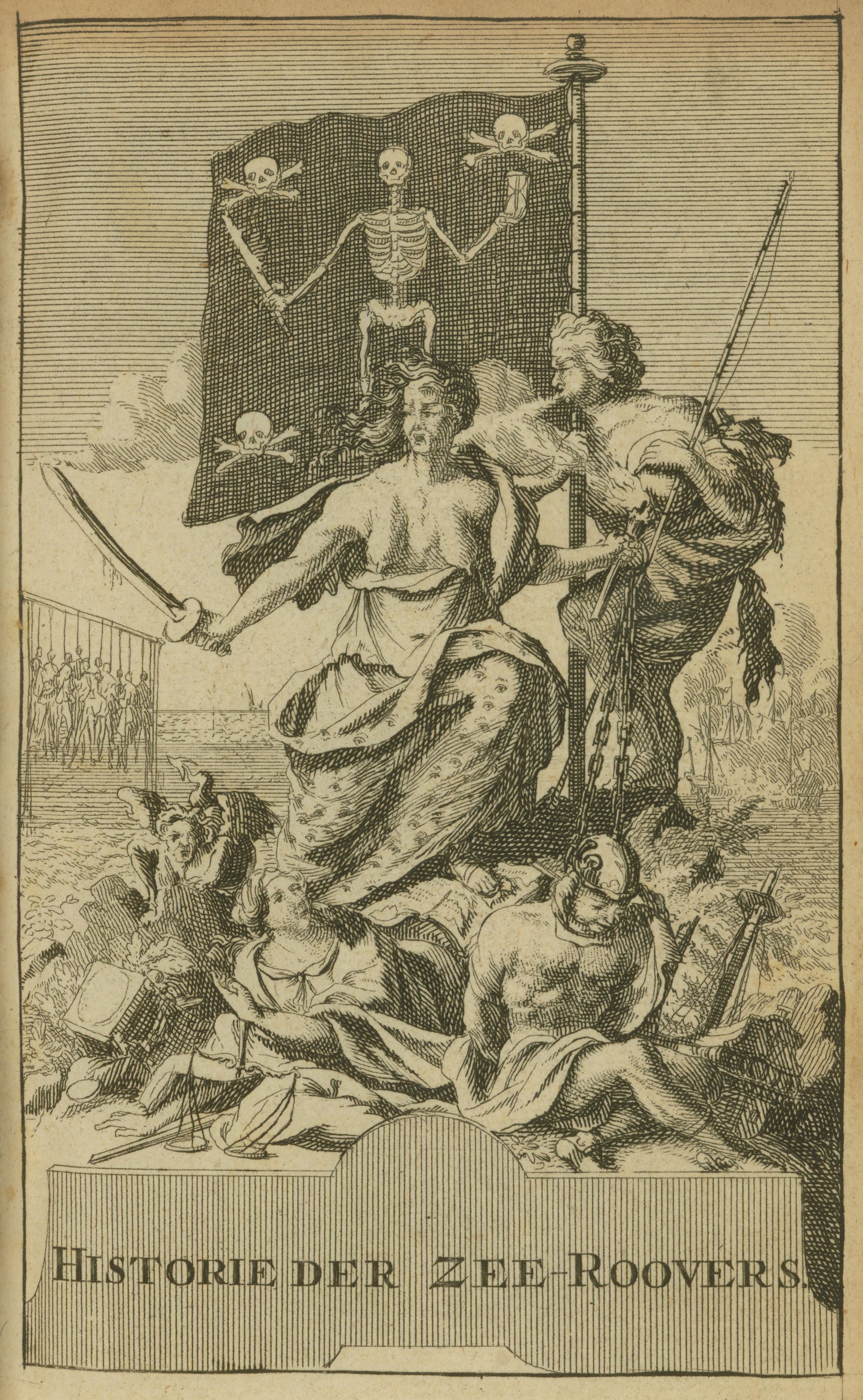

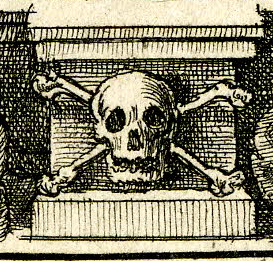

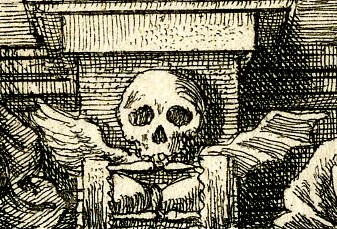

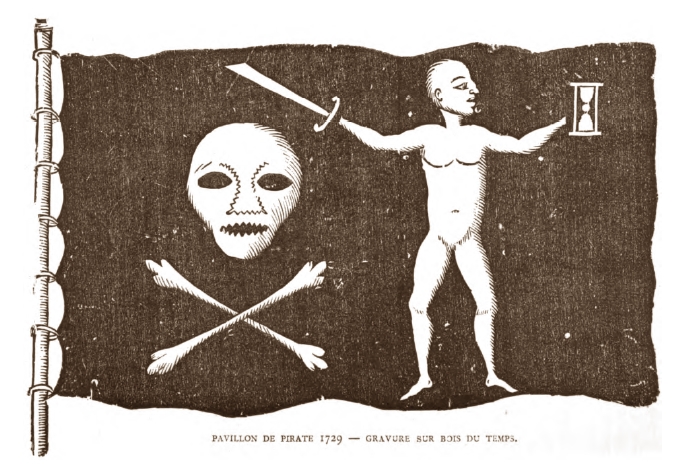

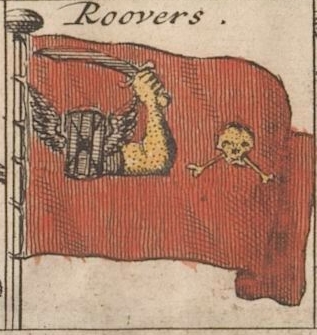

Historie der Engelsche Zee-Roovers by Charles Johnson (Amsterdam: Hermanus Uytwerf, 1725).

Strangers, who are ye? Whence sail ye over the wet ways? On some trading enterprise, or at adventure do ye rove, even as sea-robbers, over the brine, for they wander at hazard of their own lives bringing bale to alien men?

—Homer, Odyssey, book III (8th century BC, earlier oral tradition: translated by S. H. Butcher and Andrew Lang)

For in early times the Hellenes and the barbarians of the coast and islands, as communication by sea became more common, were tempted to turn pirates, under the conduct of their most powerful men; their motives being to serve their own cupidity and to support the needy. The would fall upon a town unprotected by walls, and consisting of a mere collection of villages, and would plunder it; indeed, this came to be the main source of their livelihood, no disgrace yet being attached to such an achievement, but even some glory.

—Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, book 1, chapter 1 (5th century BC: translated by Richard Crawley, 1952)

[M]uch less would pirates coming to his land be let go scatheless for long, men whose care it was to lift their hands and seize the goods of others, and to weave secret webs of guile, and harry the steadings of herdsmen with ill-sounding forays.

—Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica, book III (3rd century BC: translated by Robert Cooper Seaton, 1912)

For the Illyrians [the sea rovers of Queen Teuta] were not then the enemies of this people or that, but the enemies of all mankind.

—Polybius, The Histories, II:12 (2nd century BC: translated by W. R. Paton, 1922)

As if a man that lies at the mercy of common Pirates [praedonibus: of the robbers or plunderers], should promise them a certain Sum of Money for the saving of his Life: ‘Tis no deceit to recede from it, tho’ he had given his Oath for the performance: for we are not to look upon Pirates [pirata] as Open and Lawful Enemies: but as the Common Adversaries of Mankind [communis hostis omnium]. For they are a sort of men with whom we ought to have neither Faith, nor Oath in common.

—Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Officiis 3:29.107 (44 BC: translated by R. l’Estrange, 1720)

Not contented that suddenly he was become rich, [as] of a needy [person] he practiced piracy [piraticam] against his own Country.

—Marcus Junianus Justinus, Trogi Pompeii Historiis, book XXII (2nd century AD?: translated by N. Bailey, 1732)

For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, ‘What thou meanest by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, while thou who dost it with a great fleet art styled emperor.’

—St. Augustine, The City of God (early 5th century AD, repeating a story told by Cicero in de Republica five centuries earlier.)

In the same year, the pagans [Danes, Vikings], coming from the northern regions to Britain with a naval armament, made descents in all quarters, plundering, ravaging, and slaughtering, like most cruel wolves, not only beasts of burthen, oxen and sheep, but priests and Levites as well, and multitudes of monks and nuns.

—Roger de Hoveden, Annals (post 1189?, of the year 793 AD: translated by Henry T. Riley)

Still they killed a great many people and made great depredations on the shore.

—The Saga of the Jómsvíkings (12th century AD, of the 10th century: translated by Lee M. Hollander, 1955)

…who the malefactors and disturbers of our peace were, who being in two cogs of Campen wickedly and craftily committed divers robberies, depredations, discords, and slayings of many of our lieges along the coasts of the aforesaid country…

—Patent Rolls, 48 Ed. III. Pt. I, m. 2 d. (1374: from Marsden, Documents Relating to the Law and Custom of the Sea. The term pirate does not appear to be used in the Middle Ages in reference to the practitioners of piratical acts until the 15th century.)

I mene pyratys of the Se, Which brynge folk in pouerte.

—John Lydgate, The Pilgrimage of the Life of Man (1426: from the French of Guillaume de Deguileville, 1330, 1355)

…which notwithstondyng, divers and monyfold spoliations and robberies [have] been daily had, committed, an doon uppon the se unto the said subgettis of the said most high and myghty princes, his most dere cosyns, as well by their enemyes as by other pirattis and robbers…

—Patent Rolls, 6 Hen. VII, m. II d. (1490: from Marsden, Documents Relating to the Law and Custom of the Sea.)

Because, upon the relation of some of our lieges we are informed that many spoilers, pirates, exiles, and outlaws, arrayed in warlike fashion on the sea, have there assaulted out subjects and faithful lieges, spoiled their ships, goods, and merchandise, and are daily busying themselves and intending with all their strength to assault, rob, and spoil them…

—Patent Rolls, 3 Hen. VIII, pt. I, m. 7 (1511: from Marsden, Documents Relating to the Law and Custom of the Sea)

Her Majestie, understanding by the grevious and sondrie complaints made by her subjects of the great spoiles by them dailie sustained at the hands of such as now of late hath so infested the narrowe seas…Wherefore her Majestie’s pleasure and commandment is that, yf you shall finde any notorious pyrates at the seas, you do apprehend them…

—Landsdowne MSS. 155, f. 166 (1576: from Marsden, Documents Relating to the Law and Custom of the Sea)

Pirate: [the word] signifies one who goes to sea for adventure [daring enterprise or hazardous exploit]…the word was not in ancient times one of ugliness and vituperation, being piracy exercised by industry and right, a private war of the strongest against the weakest.

—Nicot, Thresor de la langue française (1606: author’s translation)

Moreover, pirates are those who range the seas without licence from their prince; who when they are met with, are punished more severely by their own lords, then when they fall into the hands of strangers.

—Sir Richard Hawkins, The Observations of Sir Richard Hawkins, Knight (1622: regarding his South Sea voyage of 1594)

And the pyrate pillaged Phillipps’ bark…And there were aboard Morgan Phillipps’ bark divers men passengers, whereof the pyrate too but one, and 12 or 14 women, all which were ravished [raped] by the pyrate’s company…

—“The examination of Hugh Baker” in The Council Book of the Corporation of Youghal (1623: published 1878)

Yea, and many times a Pirat who are commonly the best manned, but they fight only for wealth, not for honour or revenge, except they bee extremely constrained.

—John Smith, A Sea Grammar (1627)

[A]nd therefore in England, a pirat is called a rover and robber upon the sea.

[P]irata est hostis humani generis… [A pirate is an enemy of all mankind…]

—Edward Coke, The Third Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England, chapter 49 (1644)

‘Tis true, he’s a Rover of Fortune, yet a prince, aboard his little wooden world.

—Aphra Behn, The Rover (1677: the pirate or sea rover has long been a popular romantic image)

[I]n their Company sailed also a small Algierman of 14 Guns, pitifully manned wth about 40 Moors he hath been out of Algier these two yeares, and all his Slaves being escaped from him, dares not returne, so resolves to turne Pyrat, and take every Vessell…she can master.

—Thomas Baker, Journal (1679)

Then Sir T. P. [Thomas Pinfold] said it was impossible they should be Pirates, for a Pirate was hostis humani generis, but they were not Enemies to all Mankind; therefore they could not be Pirates: Upon which all smiled, and one of the Lords asked him, Whether there ever was any such thing as a Pirate, if none could be a Pirate but he that was actually in War with all Mankind? To which he did not reply, but only repeated what he had said before. Hostis humani generis, is neither a Definition, nor so much as a Description of a pirat, but a rhetorical invective to show the odiousness of that crime.

—Matthew Tindall, An Essay Concerning the Laws of Nations (1694: concerning the trial of privateers commissioned by the exiled James II.)

Pirate: a sea rover [escumeur de mer, écumeur de mer, “a skimmer or parasite” of the sea], one who sails the sea without a commission from any Prince, to steal, to pillage.

Forban: a pirate, a sea rover [escumeur de mer], who takes from all Nations without any commission.

Corsaire: a pirate, a sea rover [escumeur de mer], who roves [va en course] with a commission from a State or a sovereign Prince.

—Dictionnaire de L’Académie française, 1st Edition (1694: author’s translations)

They [the buccaneers in the South Sea] scare shew’d one Instance of true Courage or Conduct, tho they were accounted such fighting Fellows at home.

—Privateer, Bahamas governor, and pirate hunter Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World (1712)

They villify us, the scoundrels do, when there is only this difference, they rob the poor under the cover of Law, forsooth, and we plunder the rich under the protection of our own Courage.

—attributed to pirate Samuel Bellamy by Charles Johnson in A General History of the Pirates (1726, of events of 1717: the quote is almost certainly invented by Charles Johnson, and inspired by the exchange between the pirate Dionides and Alexander the Great, as reported by St. Augustine, Cicero, and others.)

[B]ut now that war was declared against Spain, they [the pirates] would have an opportunity of enriching themselves in a legal way by going a privateering, which many of them had privately done.

—William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave Trade (1734, in reference to events of 1719)

That pirates had no God but their money, nor Saviour but their arms.

—a pirate in Ned Low’s crew, quoted in The Four Years Voyages of Capt. George Roberts (1726: the quote dates to 1722, and might be invented)

The Pyrates, tho’ singly Fellows of Courage, yet wanting such a Tye of Order, some Director to unite that Force, were a contemptible Enemy, neither killed nor wounded us a man in taking them, and must ever, in the same Circumstances, be the Fate of such Rabble.

—John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea, Brazil, & the West Indies (1735: of the capture of Bartholomew Roberts’s Royal Fortune and his crew in 1722. Roberts was killed in the action.)

“A Pirate is a Sea-Thief, or Hostis humani generis [Enemy of all mankind], who to enrich himself, either by surprise or open force, sets upon Merchants and others trading by Sea, ever spoiling their Lading, if by an possibility he can get the master, sometimes bereaving them of their Lives and sinking their Ships; the Actors wherin, Tully calls Enemies to all, with whom neither Faith nor Oath is to be kept.”

—Charles Molloy, De Jure Maritimo Et Navali (1722: Tully is a common period nickname for Cicero.)

Pirate, Corsaire ou Forban: A thief of the sea, a sailor who cruises the seas with a vessel armed for war, to steal the vessels of friends or enemies, without distinction. He differs from a privateer [armateur] in that the latter makes war as an honest man, attacking and stealing only the enemy’s vessels, and in that he is authorized by a commission from the admiral.

— Alexandre Savérien, Dictionnaire historique, théorique et pratique de marine (1758: here a privateer is referred to as an armateur, the term for one who fits out a privateer, and not as a corsaire. Author’s translation.)

Forban: a corsair, who practices piracy without a commission from any Prince, and who attacks both friend and enemy.

—Dictionnaire de L’Académie française, 4th Edition (1762: the definition of pirate is unchanged from the 1694 edition)

Lastly, the crime of piracy, or robbery and depredation upon the high seas, is an offence against the universal law of society, a pirate being, according to sir Edward Coke, hostis humani generis…The offence of piracy, by common law, consists in committing those acts of robbery and depredation on the high seas, which, if committed on land, would have amounted to felony there. But by statute, some other offenses have been made piracy also…

—William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, vol. 4 (1769)

[I]f any person, upon the high seas, or in any river, haven, or bay, out of the jurisdiction of any particular state, commit murder or robbery, on board a vessel, he shall be deemed a pirate and a felon, and shall suffer death.

—Act of Congress (1790)

As therefore he [the pirate] has renounced all the benefits of society and government, and has reduced himself afresh to the savage state of nature, by declaring war against all mankind, all mankind must declare war against him.

—The Trial of the Twelve Spanish Pirates (1834: government quoting from Blackstone’s Commentaries in the indictment.)

Noncommissioned vessels of a belligerent nation may at all times capture hostile ships, without being deemed, by the Law of Nations, Pirates. But they have no interest in the prizes they take, and the property so seized is condemned…

—Byerley Thomson, The Laws of War, Affecting Commerce and Shipping (1854: notwithstanding this reasoning, many rovers were hanged by an enemy as “pirates” in past centuries simply because they lacked a commission.)

Privateering is nothing more than piracy organized and legal.

—Théodore Ortolan, Règles internationales et diplomatie de la mer (1864)

Piracy: depredation without authority, or transgression of authority given, by despoiling beyond its warrant. [Then repeats Blackstone’s definition.]

Pirate: a sea robber… Also an armed ship that roams the seas without any legal commission, and seizes or plunders every vessel she meets.

—W. H. Smyth, The Sailor’s Word-Book (1867)

It is because a pirate is dangerous to everybody that he bears a caput lupinum, may be seized by anybody, and punished anywhere.

—Montague Bernard, A Historical Account of the Neutrality of Great Britain During the American Civil War (1870: “caput lupinum” means “wolf’s head,” and indicates an outlaw who may be killed on sight, like a wolf)

Those only are considered as principal or real pirates who use violence, or who go below to rummage for plunder, or who take part in frightening the persons robbed.

—Ernest Alabaster, Notes and Commentaries on Chinese Criminal Law (1899)

Piracy: commerce without its folly-swaddles, just as God made it.

—Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary (1911: definition originally published between 1881 and 1906)

The submarine warfare did not mean only the sinking of ships, but it was a crime against humanity in that it sank thousands of harmless merchantmen. In the whole history of warfare between nations that had never been sanctioned. It is rank piracy, and the pirates must receive the punishment.

—Lloyd George, quoted in the New York Times (1918: legal opinion was largely against the Prime Minister’s sentiment.)

Piracy suits my master, and that is all there is to it. His ship is his kingdom, he comes and goes as he pleases, and no man can command him. He is a law unto himself.

—Daphne du Maurier, Frenchman’s Creek (1942: again the popular view of a pirate as independent free-roving operator.)

Yes I am a pirate//Two hundred years too late//The cannons don’t thunder//There’s nothing to plunder//I’m an over forty victim of fate…

—Jimmy Buffet, A1A, “A Pirate Looks at Forty” (1974)

Piracy: Those acts of robbery and depredation upon the high seas which, if committed on land, would have amounted to a felony. Brigandage committed on the sea or from the sea.

—Black’s Law Dictionary, 5th Edition (1979: this definition is essentially Blackstone’s)

Piracy consists of any of the following acts: (a) any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed: (i) on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft; (ii) against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State; (b) any act of voluntary participation in the operation of a ship or of an aircraft with knowledge of facts making it a pirate ship or aircraft; (c) any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described in subparagraph (a) or (b).

—United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Article 101 (1982/1994: current international law, originally drafted in 1958 as part of the UN Convention on the High Seas)

Pirate: One who robs and plunders on the sea, navigable rivers, etc., or cruises about for that purpose; one who practices piracy; a sea robber.

Piracy: The practice of the crime of robbery and depredation on the sea or navigable rivers, etc., or by descent from the sea upon the coast, by persons not holding a commission from an established civilized state.

—The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989)

Pirate: an adventurer who sails the seas to pillage merchant ships or the coasts.

Piracy [Piraterie]: an act of maritime brigandage conducted by pirates.

—La Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé (2002)

Pirate: one who commits or practices piracy.

Piracy: an act of robbery on the high seas: also: an act resembling such robbery.

—Merriam-Webster’s 11th Collegiate Dictionary (2003)

Whoever, on the high seas, commits the crime of piracy as defined by the law of nations, and is afterwards brought into or found in the United States, shall be imprisoned for life.

—18 USC §1651 (2007, current US law: unchanged since 1909, and little changed since 1819 except for the substitution of life imprisonment for the death penalty. See UNCLOS above for current law of nations.)

Whoever, being a seaman, lays violent hands upon his commander, to hinder and prevent his fighting in defense of his vessel or the goods intrusted to him, is a pirate, and shall be imprisoned for life.

—18 USC §1655 (2007, current US law: largely unchanged since 1790.)

Whoever, upon the high seas or other waters within the admiralty and maritime jurisdiction of the United States, by surprise or open force, maliciously attacks or sets upon any vessel belonging to another, with an intent unlawfully to plunder the same, or to despoil any owner thereof of any moneys, goods, or merchandise laden on board thereof, shall be fined under this title [Piracy and Privateering] or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both.

—18 USC §1659 (2007, current US law: penalty increased from that of 1909, otherwise essentially unchanged)

Whoever, being engaged in any piratical cruise or enterprise, or being of the crew of any piratical vessel, lands from such vessel and commits robbery on shore, is a pirate, and shall be imprisoned for life.

—18 USC §1661 (2007, current US law: largely unchanged since 1909, and very similar to law enacted in 1820)

So began a tense five-day standoff in which the pirates repeatedly threatened to kill the captain.

—New York Times (2009: regarding the Somali pirate attack on the cargo ship Maersk Alabama and the taking of her captain, Richard Phillips, hostage.)

We can finally do it! We can leave this crappy town and live the life we’ve all dreamed of…Haven’t you heard? Haven’t you been watching the news? Pirating is back, my friends, swashbuckling adventure on the high sea, the stuff we’ve all dreamed about, and it’s all happening right here: Somalia.

—Cartman, in South Park, “Fatbeard” (2009)

Copyright Benerson Little 2017. Posted 7 June 2017.

Commands at Sea: The Boatswain’s Call, Pipe, or Whistle, with a Note or Two on Boatswain Speech as Well

Title page to William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, from volume one of The Works of Shakespear edited by Alexander Pope. London: Jacob Tonson in the Strand, 1725.

Ah, the Bard! As someone once pointed out in writing, and I wish I could recall who it was (unless I’m imagining or mis-recalling this), the opening to the Tempest is one of the most evocative in its brevity in all of literature. It brings ship and storm to life immediately. In related fashion, I’m pretty sure it was George MacDonald Fraser who wrote words to the effect that “Enter Mariners wet” is one of the great stage directions of all time. Or perhaps I’m confusing his observation with the former, or even inventing the former from the latter.

But, in this brief yet related digression from swordplay and swashbuckling at sea and ashore, we’re more concerned with another line in the play: “[T]end to the master’s whistle…,” that is, listen to and obey (the “Aye, aye!” spoken or unspoken) the musical commands, shrill, some said, from the ship master’s silver whistle.

Notably, it’s not the boatswain’s whistle Shakespeare mentions, but the master’s, for in the sixteenth century and into the seventeenth the boatswain was not the only officer authorized a whistle. As Nathaniel Boteler wrote in 1634 in A Dialogicall Discourse Concerninge Marine Affaires Betwene the Highe Admirall and a Captaine att Sea, first published in 1685 and known today as the eponymous Boteler’s Dialogues:

“ADMIRAL. How many be the officers that carry whistles in a ship of war?”

“CAPTAIN. They are three: The Master, the Boatswain, and Coxswain, for though the Captain my do the same at his pleasure, yet it is neither usual, nor necessary.”

By the late 17th century, it appears that the silver whistle or “call” was used primarily by the boatswain.

Dutch boatswain’s (or other officer’s) whistle, early 17th century, Rijksmuseum.

Before going further, and with no offense intended to anyone, I want to make sure that readers understand that boatswain is pronounced “bos’n” or “bosun.” I’ve heard “cocks-wayne” rather than the correct “cox’n” (cockswain, one who commands and helms–steers–a ship’s boat) before–including from persons well-educated but clearly un-nautical, not to mention clearly forgetting the first rule of the pronunciation of a new word: look it up!

The boatswain’s whistle, both as a badge of office for any ship’s officer as well as a functional instrument with a large variety of “calls” for ordering hands about, has been around since at least the 13th century according the USN Bluejacket’s Manual (1941 edition), in more or less similar traditional form. It also notes that, although the whistle is commonly referred to as the boatswain’s pipe in the US Navy, the term “call” in reference to it dates to “about” 1671. A writer commenting in 1679 upon the lack of religious fervor among English seamen during the English-Dutch war at sea 1672 to 1673, complains that “a Lieutenant’s Command for a Rope for the Boat, shall be sooner answered with Boatswain’s Call, than the Bell for Prayers…”

However the Reverend Henry Teonge, chaplain aboard the HMS Assistance 1676 to 1678, still referred to it as the boatswain’s whistle: “He had a neat coffin, which was covered with one of the King’s jacks, and his bo’sun’s silver whistle and chain laid on the top (to show his office) between two pistols crossed with a hanger drawn.”

The English boatswain had other badges of office as well, including a short cane or “bamboo,” its tip whipped with marline, for encouraging laggard seamen by cracking it on their backs and pates, although sometimes a simple rope’s end served as well. And there was the cat-of-nine-tails too, a dark badge of office best kept out of sight except when in use. But it was the boatswain’s whistle that was his definitive badge of office, and I’m sure that boatswains of the past were just as proud of their silver call as boatswain’s today are: “It is not so much by his fine Silver-call, as the illustrious Chain that it hangs by, that is the distinguishing Badge of his Post, and which he’s as proud of as my Lord Mayor is of his, and prouder,” wrote Ned Ward in 1707.

The whistle was an important means of directing seamen about their duties. Again, Ned Ward: “The Boatswain is a Kind of a Jack with a Box, for let him but whistle once, and you have a hundred or more Cartesian Puppets, pop up upon Deck, and run about, and streight disappear again in an Instant.”

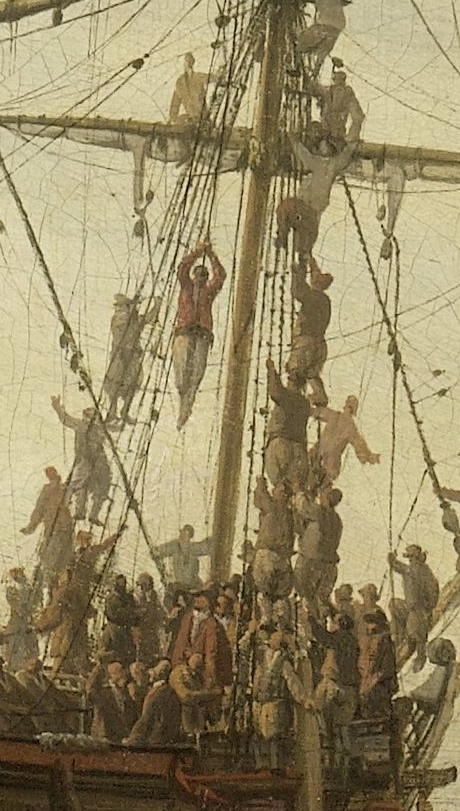

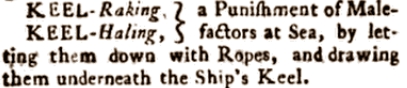

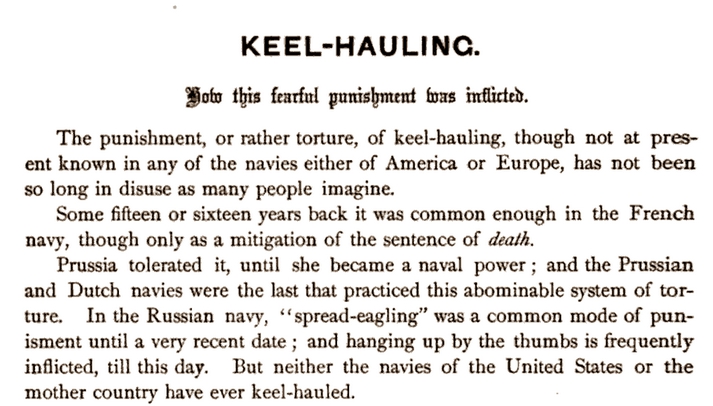

In the 17th and 18th centuries an English boatswain’s duties included the custody, keeping, repair, and management of all rigging, anchors and cables, and sails; the hoisting in and out of cargo, stores, and boats; the management of all of the ship’s colors; the calling up, via his whistle, of gangs, watches, &c. for, as Boteler put it, “exertions of the their works and spells (as they call them), and to see that they do them thoroughly; and to keep them in peace in in order with one another.” This last duty was that of what on land was handled by the Provost Marshal. At sea, it was the boatswain who punished seamen for their shortcomings. This included everything from flogging wrongdoers to placing them in the bilboes to ducking them at the main yardarm. In the Dutch navy, the boatswain’s duties include keelhauling as well (see “Keelhauling, in Living Color”).

In battle the boatswain and his mates, along with some of the other crew if the occasion warranted, were tasked not only with repairs to the rigging, but often with managing the sails. Shortened sail was typically used in battle in order to reduce the number of crewmen required to manage it, leaving the majority to handle the guns great and small, and the small arms as well.

At sea aboard USS George Washington (CVN 73) Sep. 9, 2002: Boatswain’s Mate 3rd Class Bethany McDonald. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate Airman Jessica Davis.)

In the modern US Navy, the boatswain–thankfully, after a brief period of insanity in which ratings were abolished, they’re now restored–has similar duties, in particular in regard to the various rigging aboard modern ships, the hoisting of boats and stores, and so on. The boatswain’s pipe remains ever present, and modern US Navy boatswain’s calls, performed by the US Navy band, can be found here.

The most common call I remember was “Piping the Side,” that is, the piping of a captain, admiral, or on occasion, some dignitary over the side during a formal ceremony shipboard or ashore. I remember various other calls shipboard as well, on both surface ships and submarines, but for the life of me I can’t remember them in detail except that “All Hands” was common, or perhaps it was “Pass the Word,” and, like everything else, the calls came over the 1MC (the general PA aboard a US Navy ship or shore command) except in the case of the piping the side ceremony, for we were always present for them.

But boatswains then and now had other means to motivate seamen: language, particularly when spiced with “cursing and swearing.” Sailors in general have long been known for their use of foul language, and boatswains in particular had, and have, a reputation for creativity, eloquence, wide vocabulary, and, as often as not, lyricism in their swearing. Ned Ward noted that:

“He must certainly believe there can be no such Thing as Hell-fire under Salt-water, else he would never be giving himself so oft as he does to the Devil; but how frequently soever he damns himself, he is sure to damn others much oftener. In short, he’s a Fellow that will throw away ten times more Oaths and Strokes in hoisting out a Barge, than in boarding an Enemy.”

The boatswain’s excuse for his language is a simple one: “But, Zounds, he’ll cry, what would have me do? A man without Noise, is a Thing without a Soul, and fit for nothing but a Pissing-Post.”

As for my own experience, I never knew a real US Navy boatswain, at least not a Chief Boatswain’s Mate, who couldn’t out-swear anyone except another boatswain. A boatswain’s work–dealing with fouled lines, for example–naturally inspires foul language, which in turns lubricates the work at hand and helps get it done. At times I’d swear it has motivated not only crew but rigging or equipment itself.

My favorite example of a boatswain’s cursing, however, or perhaps my second favorite (I’ll save a particular modern description for a later post), may be that of Ned Ward’s Royal Navy boatswain, whose elegant oxymoron is straight to the point:

“Get up, all Hands to Prayers, and be damned.”

Indeed.

REFERENCES (Not Cited in Detail Above)

Anon. Observations on the Last Dutch Wars, in the Years 1672 and 1673. London: 1679.

Nathaniel Boteler. Boteler’s Dialogues. Edited by W. G. Perrin. London: Navy Records Society, 1929.

Benerson Little. Chapter 14, “Tarpaulin Cant and Spanish Lingua,” in The Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish Main, 1674-1688. Washington DC: Potomac Books, 2007.

Henry Teonge. The Diary of Henry Teonge. Edited by G. E. Manwaring. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1927. (Teonge’s original manuscript was first published in 1825.)

United States Navy. Bluejacket’s Manual. 1941.

Ned [Edward] Ward [By the Author of the London Spy]. The Wooden World Dissected in the Character of a Ship of War, 7th ed. London: Booksellers of London and Westminster, 1760. Originally published in 1707.

Copyright Benerson Little 2017. Last updated May 3, 2017.

Fencing Books For Swordsmen & Swordswomen

The content in this post is more background on than digression from the general subjects of this blog–swordplay and swashbucklers–, for what is either without fencing technique? The following fencing books are my recommendations for fencers across the spectrum, from early modern historical to “classical” to modern “Olympic” competitive. It includes sections on the modern Olympic weapons, classical fencing, rapier, smallsword, various cut & thrust, theory, Japanese texts, and more.

The list below, although quite long, is not exhaustive—there are many good fencing books not listed (and some more bad than good as well). Some are not listed simply because I have not yet read them. The history list in particular is abridged due to sheer volume, but less so than in past years, and I have not yet begun to include much in the way of mid-19th century works or of books on swords as opposed to swordplay. Fencing books can be very useful, but are no substitute for proper instruction and diligent practice, as I learned from my fencing masters, Dr. Francis Zold and Dr. Eugene Hamori. See the end of the list for suggestions on acquiring the books listed here, or for that matter, many books in general.

The first fencing book I ever read, in 1975 or 1976, was Bob Anderson’s All About Fencing, along with a beginning text by Nancy Curry or Muriel Bower, I can’t recall which, probably the former. These were followed by, once I started fencing in 1977 under Dr. Zold at USC, either Curry or Bower’s book (the latter I think, given Bower’s association with USC), then Charles Selberg’s Foil (and when it was published, his Revised Foil), Michel Alaux’s Modern Fencing, Marvin Nelson’s Winning Fencing, and, in 1980, Imre Vass’s Epee Fencing, soon followed by Laszlo Szabo’s Fencing and the Master. From that point my interest in fencing texts exploded.

My earliest years of fencing education, however, were dominated by fencing lessons, verbal instruction, and oral histories, not fencing books. Notably, my epee instruction was derived in large part from Vass via Dr. Hamori’s own knowledge of the weapon and in consultation with his close friend József Sakovits who was one of the world’s greatest epeeists and later Hungarian national coach. The general method of instruction used by my masters was derived directly from Szabo, his master Italo Santelli, and other notable Hungarian masters such as Gyorgi Piller–yet never for four years were the works of Vass or Szabo recommended to me. They were, in essence, above my ability at the time.

As Italo Santelli put it, fencing is something you do, not something you write (and therefore read) about! Thus were my early years filled with learning to fence not by reading but by fencing, fencing, and more fencing. That said, the study of fencing texts does have an important place in learning to fence: it broadens one’s knowledge of the subject. Fencing books provide a map to the world of swordplay. They can also point out errors in technique, training, and tactics (although a fencing master is always better for this), and can reorient one’s perspective in certain cases.

Associated fencing quotations can be found here.

N. B. If you take the broad study of swordplay seriously, you will find yourself compelled to consider the following questions major and minor, for example: Does offense or defence put the fencer in the strongest position, or does a balance between the two? Should the fencer extend fully before lunging or simply begin with the point, extending and lunging near simultaneously? Where should the fencer primarily look when fencing — at the hilt and blade, at the eyes (if they could be seen), or broadly at the whole, or in combination, shifting from one to another? Should the fencer emphasize power (strength and speed) or finesse, or both? Tactically, is the strategic fencer or the opportunistic fencer generally superior?

Essays on Fencing & Life

So rare are these essays that I’ve found only two to list so far, although occasionally the subject is touched upon in prefaces to fencing books. I’ve listed Lambotte’s first, as her entire short work is on the subject. The first third of Bertrand’s book qualify as an essay on fencing & life, thus the book is the only one to get a double entry.

Arguably, Bazancourt’s Secrets of the Sword and Burton’s The Sentiment of the Sword occasionally connect fencing to life in general, and Gravé’s Fencing Comprehensive has a sense of this as well. All three are noted below.

L’Escrimeuse by Emma Lambotte, 1937. A delightful essay on fencing, on being a woman fencer, on fencing’s connection to and reflection of life, and on the characters of various fencing nationalities, among many other brief subjects. Mme. Lambotte was a noted Belgian poet and the muse and patron of painter James Ensor.

Cut and Thrust: The Subtlety of the Sabre by Leon Bertrand, 1927. The first five chapters of Bertrand’s book qualify as essays on fencing and life, ranging from a defense of fencing as sport to a defense of dueling to physical and mental exercise. See the full entry below.

Modern Epee

Why have I placed Modern Epee—that is, epee as fenced from the 1930s to the present in its various forms—first among books on technique? Because it’s the best starting point for most budding fencers today, even if their ultimate goal is classical or historical fencing. It is by far the most popular modern competitive weapon (it looks like swordplay, its judging is simple, it much more resembles sword-fighting with sharps than either modern foil or saber, it is very “democratic” in that the weaker fencer always stands a chance, as some have put it), and—if taught appropriately via a classical foundation as it should be—is also an excellent foundation for historical and classical fencing. Modern competitive foil and saber have become largely useless for this, both as fenced and as taught, for they’ve given up the classical notion derived from combat that attacks in invitation–with the point non-threatening and/or the arm not extended or extending–would be suicidal with real weapons.

It should be noted that some modern epeeists consider not only classical epee technique (point d’arrêt technique, especially non-electrical, and true dueling technique), but also “modern classical” (electrical pre-Harmenberg, so to speak) technique to be obsolete. This narrow view has no basis in fact except to some degree in the case of some elite (world class, that is) epeeists. Purely classical and modern classical epeeists can, and often do, fence as far as a solid A, or national, level, and classical technique is the foundation of elite epee technique. In fact, elite women’s epee retains a significant amount of so-called classical technique, and the compiler of this list is well-acquainted with a Greek-American epeeist some 80-plus years old whose classical, very old school straight arm dueling technique can still give even young elite epeeists fits.

Note, however, that the definition of classical fencing has changed over time and continues to change today. More than a century ago foil was considered the classical school and epee the modern, and French duellists of a century ago were classified according to three schools: foil, foil-epee, and epee! In fact, one need only read Achille Edom’s 1910 book on epee fencing (see below) to realize that much of what is considered new in epee is in fact more than a century old. In other words, epeeists should not consider older epee texts, nor any epee style of the past century or more, as unworthy of practical study, modern fads, to which epee is highly susceptible, notwithstanding.

Fencing with the Epee by Roger Crosnier, 1958. A thorough description of modern classical epee technique, still very useful today. Prof. Crosnier’s book on foil fencing (see the Foil section) should be read hand-in-hand with his epee text.

Epee Fencing: A Complete System by Imre Vass, 1965 in Hungarian, 1976 1st English edition, revised English editions 1998, 2011. The most thorough epee text ever written. That said, highly recommended for epee coaches at all levels, recommended only with caution for intermediate to advanced fencers (at least three to five years or more significant experience)—but not for beginners. There is much useful, often profound, material, but some sections can be skipped entirely by some fencers, and others require sufficient epee fencing experience in order to profit from them. The revised editions were edited by fencer and publisher Stephan Khinoy, and amplify and supplement the original text in places.

The latest edition suggests the need for such classical training today, in spite of the so-called “new paradigm” (see Harmenberg below, his book was also originally published by Khinoy). I agree. Even for those relatively few fencers (as compared to the entire body of epeeists) who wish to and are able to emulate Harmenberg’s sport methods, a solid base of “modern classical” epee training is still necessary. For most epeeists, even superior amateurs, modern classical technique is all they’ll ever need.

Again, caution is advised when studying the book; it’s best to have a solid understanding of fundamental epee technique and theory before reading it. In fact, it helps to understand the Italian school in order to understand Vass’s theoretical framework: Luigi Barbasetti’s book on foil (see below) is a good start. Vass trained international medalists József Sákovics and Béla Rerrich, both of whom went on to become leading epee masters and national coaches, the former in Hungary, the latter in Sweden, with numerous international champions to their credit. He also trained four-time Olympic gold medalist in epee Győző Kulcsár, who later as a fencing master trained two-time Olympic gold medalist in epee Timea Nagy. József Sákovics, considered by many to be the first “modern” epee fencer, died in 2009, Béla Rerrich in 2005, and Győző Kulcsár in 2018.

La Spada: Metodo del Maestro Caposcuola Giuseppe Mangiarotti by Edoardo Mangiarotti, the Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano, Scuola Centrale Dello Sport, and Federazione Italiana Scherma, 1971. Epee as taught by the famous Guiseppe Mangiarotti: a thorough exposition of his method. Beginner-friendly, too, at least if you read Italian or have a working knowledge of fencing technique and language along with a background in Romance languages other than Italian. Includes excellent illustrations of blade positions, better perhaps than in any other epee text. (Side note: the book even includes illustrations from the works of Vass and Szabo. Kingston and Cheris in this section also have excellent illustrations of blade positions.)

Prof. Mangiarotti, who studied under Italo Santelli as well as under other masters Italian and French, was an Olympic fencer, seventeen-time Italian national epee champion, father of famous champion Edoardo Mangiarotti as well as of noted fencers Dario and Mario Mangiarotti, and founder of a famous epee school in Milan, still in existence, that blended the French and Italian schools and produced champions for decades. Edoardo won 13 Olympic medals and 26 World Championship medals, and was known for his fluid, very Italian footwork as well as for his strategy of attacking hard and fast early on to get touches, then playing a defensive game. Highly recommended: it is my second-favorite “modern” epee fencing book. See also Mangiarotti and Cerchiari in the “Combined Modern Epee, Foil, and Saber Texts” below. For the French school, see Alaux and Cléry in the same section.