Home » Writing

Category Archives: Writing

“The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow” by Howard Pyle

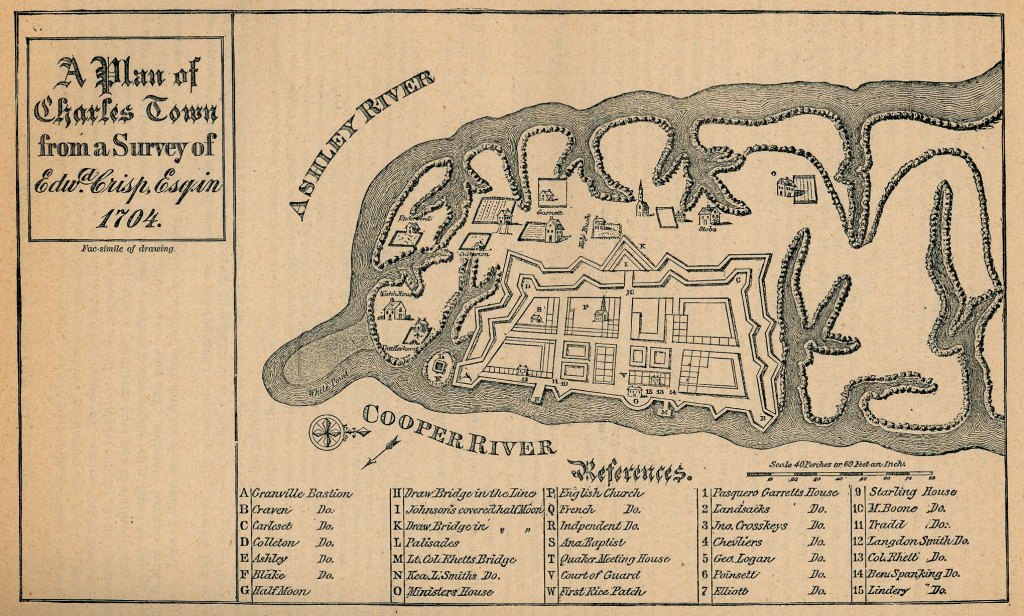

And indeed he was a picturesque — and picaresque! — fellow, the buccaneer! Howard Pyle’s painting of this romantic sea rover has influenced the imaginations of half a dozen generations of readers, writers, illustrators, costume designers, film-makers, and game designers. Currently on view at the Delaware Art Museum, the painting was one of four created for an article, “The Fate of a Treasure Town,” also by Pyle, published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1905.

In fact, the paintings accompanying the article are some of Pyle’s most famous buccaneer and pirate images. In addition to the picturesque buccaneer, there is “An Attack on a Galleon,” “Extorting Tribute from the Citizens” (used as the cover of The Buccaneer’s Realm, for what it’s worth), and “So the Treasure Was Divided.” Of the most famous paintings of his buccaneer, as opposed to pirate, series, only “Which Shall be Captain?” for “The Buccaneers” by Don C. Seitz, in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, January 1911, and “How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas,” Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899, are missing. (High resolution images are available on Wikimedia Commons.)

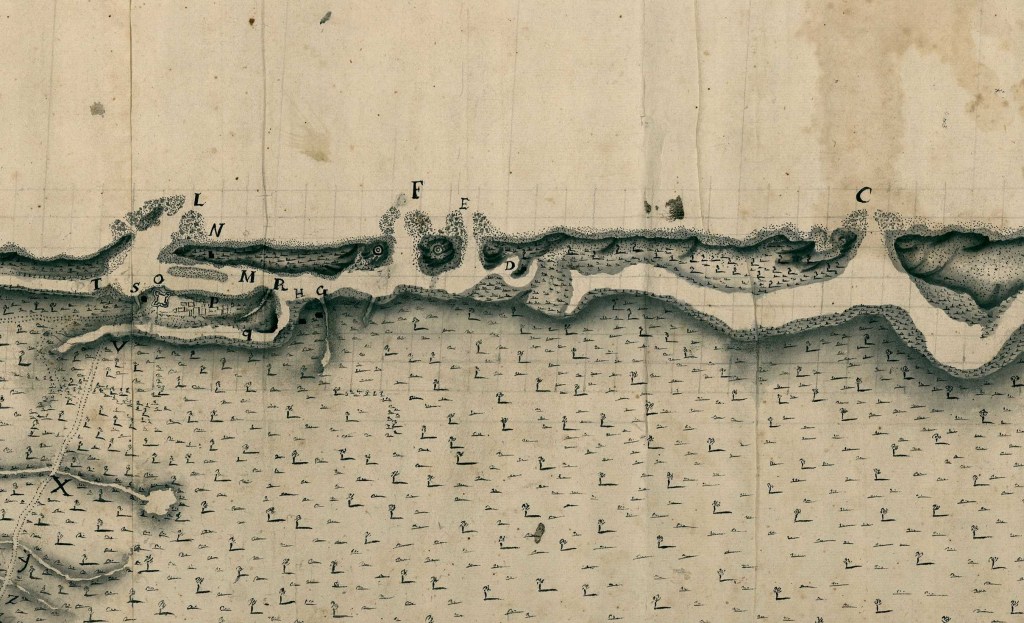

Pyle’s article opens with romantic tropical buccaneering scene-setting, then shifts in detail to the sack of Cartagena de Indias in 1697, a privately-funded French privateering expedition that was composed of hired ships and troops of the French navy and army, with a large body of French buccaneers and Caribbean militia in support. The Baron de Pointis, commander of the expedition, swindled the buccaneers out of their agreed share, so they returned and extored more treasure from the citizenry. Pyle’s painting, “Extorting Tribute from the Citizens,” shows buccaneers actively engaged in this pursuit. (On a side note, the painting was used for the dust jacket of The Buccaneer’s Realm, my second book.)

But few people have actually the read the article or even know about the sack of Cartagena de Indias, and it’s the images themselves that have caught our imagination. In particular, film-makers, illustrators, and Disney have borrowed heavily from the paintings: from The Black Pirate of Douglas Fairbanks and the Captain Blood of Michael Curtiz, to Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean attraction and films, to the sea rover art of Don Maitz, Pyle’s influence is impossible to deny.

From a historical standpoint, the paintings are far more evocative than accurate, although clearly Pyle attempted to get historical details correct. But this wasn’t easy. He had to interpret written descriptions and also — the bane of truth-seeking historians and researchers everywhere! — appeal to popular tropes as well. For popular works, some degree to catering to popular expectations is considered mandatory, or so I’ve been advised (and immediately resisted, bound by nature to do my best to keep within the limits of fact and fact-finding, at least as much as possible).

For Pyle, it was not the buccaneer or pirate’s sea roving escapades that made him appealing: “It is not because of his life adventures and daring that I admire this one of my favorite heroes; nor is it because of blowing winds nor blue ocean nor palmy islands which he knew so well; nor is it because of gold he spent nor treasure he hid. He was a man who knew his own mind and what he wanted.”

He conveyed this well with his picaresque — sorry, picturesque — buccaneer even if it appears that the young man evokes a purely romantic image of a sea roving adventurer rather than a real one.

Let’s take a quick look at his arms, accoutrements, and clothing and compare them to the historical. We’ll begin with his hat. Spotting the red ball tassels, we assume the hat is intended to evoke Spain — it’s the somewhat tropish hat of a Spanish flamenco dancer or mounted matador. Perhaps the buccaneer captured it, or, I think more likely, the buccaneer is in fact a Spaniard, a mestizo perhaps. We know that there were Spanish renegados among the buccaneers. Let’s keep this in mind as we look at the rest of him.

He’s wearing two gold earrings — small simple hoops. Most European-derived buccaneers did not wear earrings, with the occasional exceptions of the Dutch (single pearl, single ear) and fops (single pearl, single ear). However, all too often our impression of pirates is influenced by our ethnocentrism: some Africans, Native Americans, mulattos, and mestizos in the Americas did in fact wear earrings. Pyle probably added earrings as part of the expected pirate cliché, but to my mind, the earrings, considered historically, are more evidence that this buccaneer is a Spanish mestizo renegade, as is the perhaps fanciful bracelet on his wrist. His dark hair and olive skin — also “Spanish” clichés — are to me more evidence of his Hispano-American origin.

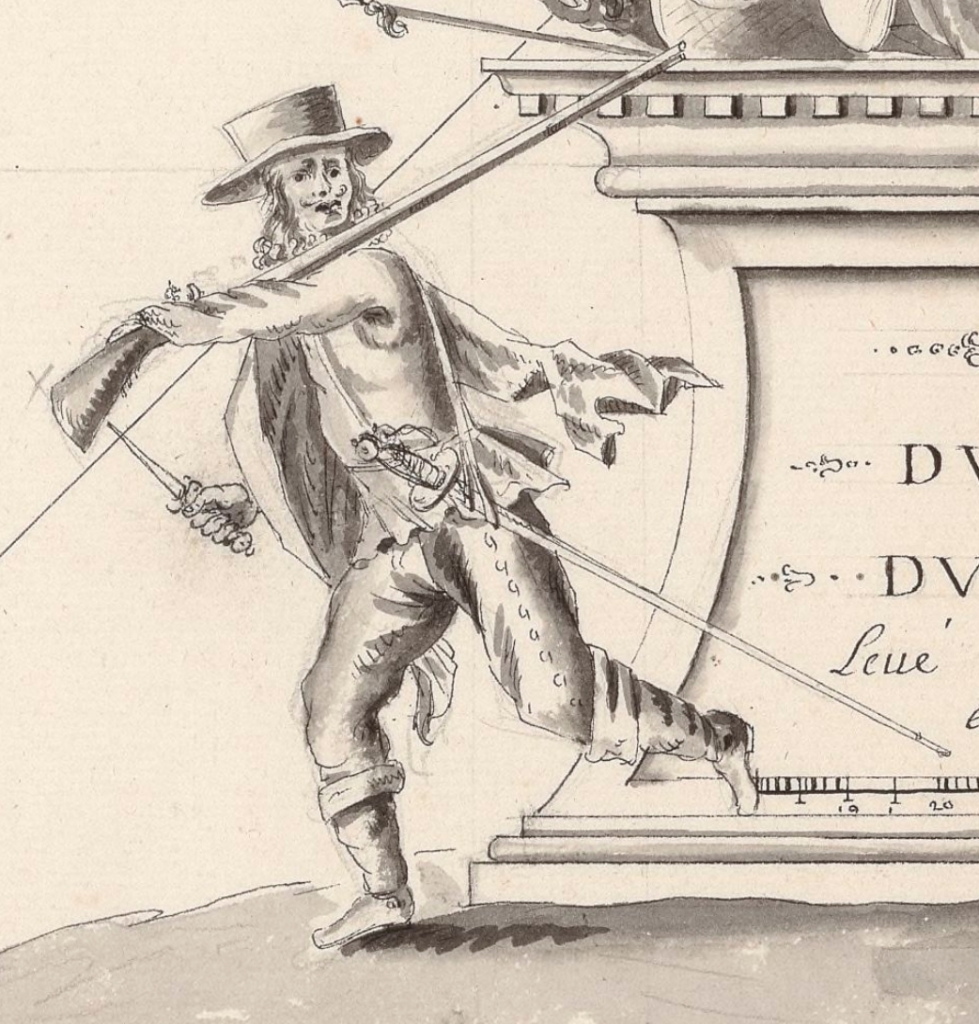

He has a red cloak over his shoulders, but would a buccaneer wear one? Probably not in the daytime, given the highs in the upper 80s and lows in the upper 70s year-round in Cartagena de Indias, although in some areas of the Caribbean cloaks, jackets, blankets, “ruggs,” &c were worn or used, typically at night. That said, a 1680s image, if not eyewitness then at least based on eyewitness descriptions does show a Spanish pirate or privateer with a cloak! More on this below.

Further, French priest and eyewitness Jean-Baptiste Labat described the admiral of the Armada de Barlovento in the Caribbean as wearing a cloak, but he was an old man and perhaps needed the cloak to keep his old bones warm at sea. And Spaniards wearing them are depicted in period images of New Spain, see the last image below for example. Perhaps, as with the Spaniard’s ruff which was often added historically as a satirical symbol — Spaniards no longer wore ruffs –, Pyle added the buccaneer’s cloak as a mere symbol of dress to indicate that the man is a Spaniard. This isn’t the first time Pyle put a cloak on a buccaneer: he also did so in his painting, “How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas,” Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899.

His “musket” is a bit of an anachronism: it is a Jaeger or Jaeger-type hunting rifle. Developed in the late 17th century in the region later to become known as Germany, there is no indication they were ever used by buccaneers. These Caribbean sea rovers used the long fusil boucanier, especially among the French, and various other muskets at times. However, there are instances of carbines (Sp. carabinas) in use on occasion at sea and ashore, and we will assume this is what Pyle meant to represent. His pistol could represent any number of sea pistols in use at the time, and is close to their common size. Its lock is indeterminate, but it hints of a Spanish Miquelet style.

His rapier, or possibly broadsword, is a shell-hilt, of what could be a Spanish-style doble concha, although the true cup-hilt (taza) was far more common. All or nearly all English, French, and Dutch buccaneers carried cutlasses, although there are documented indications of a few exceptions for smallswords and broadswords. However, the rapier — espada ropera — was still in common use in Spain, Portugal, and Spanish-governed parts of Italy at the time, not only among gentlemen (and most Spaniards considered themselves gentlemen!), but also among soldiers and almost surely among some seamen and artilleros. In fact, the eyewitness, or nearly so, image below of a Spanish privateer or pirate from the 1680s shows him wearing a Spanish rapier. Curved quillons were uncommon on Spanish swords of the era, although they did begin to show up on some at the end of the 17th century. Again, although for Pyle the rapier may have been a necessary trope, historically it would point the buccaneer being a Spaniard, Portuguese, Italian, or Corsican.

His sash is a bit wide, at least from what eyewitness images suggest, but his belt is correctly worn over it. The pouch or box on his right may be a cartouche box worn on a strap in a rather un-buccaneer style. His breeches, buttoned at the sides, are quite typical of those shown worn by Spaniards in the era, although Pyle may have depicted this style to evoke the swashbuckler or pirate as he did in other paintings, “I Had Met My Equal” for example.

And last, his sandals: most buccaneers, according to eyewitness descriptions and images, wore conventional shoes, or boucanier shoes made from skin pulled from the hocks of hogs (see here for details), or went barefoot, at least among the poorest sort. However, as noted not all buccaneers were English, French, or Dutch. Some were Spanish renegades, including Spanish Native Americans and mestizos, and we know that some of both groups wore sandals at the time.

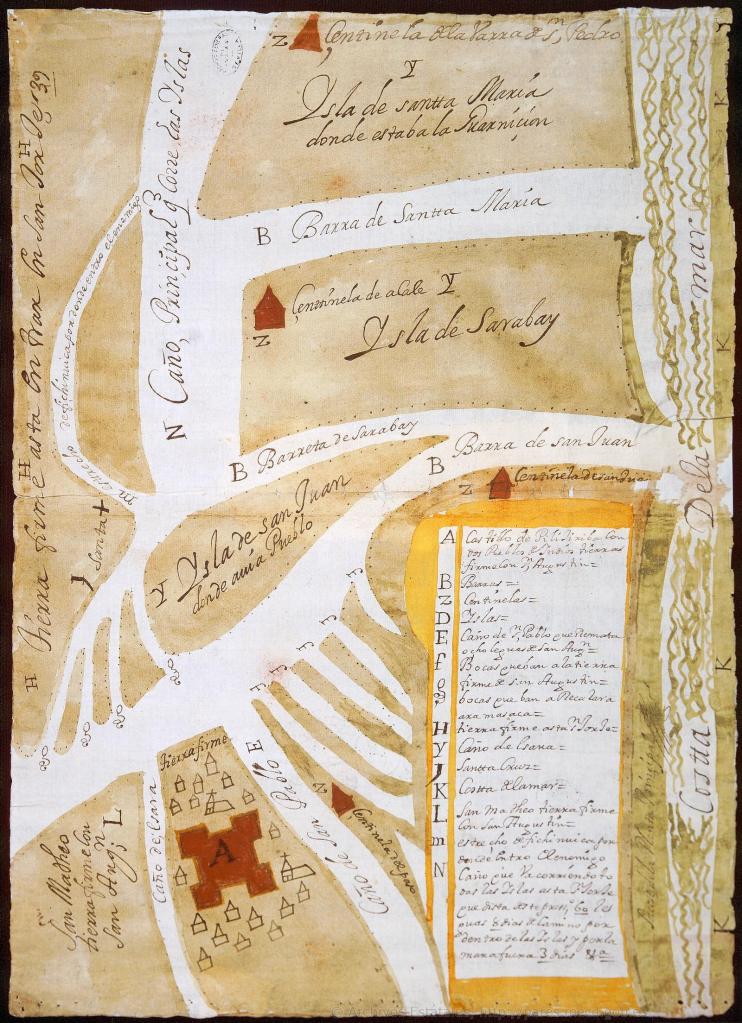

The image below was drawn by a French engineer in the 1680s, almost certainly based on local eyewitness accounts of French pirates or privateers who attacked Nipe on Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti). There is no chance Pyle ever saw this image, yet his picturesque buccaneer evokes it well! The Spaniard is even wearing a cloak! Many Spanish pirates and privateers — most, some eyewitnesses noted — were men of color: Native Americans, mestizos, Africans, and mulattos. Is this what Pyle intended, a Spanish or mestizo renegade buccaneer? I can’t be entirely certain, but the evidence and my gut assure it is.

Bookends, Bookcovers, & More…

The painting has inspired a variety of objects and art, ranging from bookends to bookcovers to game miniatures. The bronze-clad bookend below, “Pirate’s Den” by Peter Manfredi (1930) for the Pompeian Bronze Co., is a three dimensional copy of Pyle’s painting. This example is one of two variants; the other has part of the background removed.

The Pompeian statuette bookend below, “Buccaneer” by Peter Manfredi (1930), was clearly inspired by Pyle’s painting. On the left is “Miss Pirate” by the same sculptor and year for Pompeian Bronze Co., Brooklyn.

In The Black Swan (20th Century-Fox, 1942), only loosely based on Rafael Sabatini’s novel of the same name, Tyrone Power’s costume is clearly based on, and probably an homage to, Pyle’s famous painting. The hat with tassels hanging from it, the cape, the sash, the rapier, are all clearly intended to evoke Pyle’s picturesque buccaneer.

The image has been used often on the covers of trade paper editions of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini. The one below is published by the Naval Institute Press. Pyle’s painting doesn’t evoke the urbane and sedulous Captain Peter Blood, but it does evoke the buccaneers he led. In fact, part of the novel takes place during the sack of Cartagena de Indias, although Sabatini moves the attack on the beautiful city up in time.

The painting inspired the cover of a mass market edition of Cup of Gold by John Steinbeck, a fictional, and quite literary, account of famed buccaneer Henry Morgan.

CrossGen published a series of six comic books 2003-2004 by Chuck Dixon, Steve Epting, and Frank D’Armata featuring a Spanish female pirate hunting captain, Donessa Cinzia Elena Marie Esperanza Diego-Luis Hidalgo (seriously!). Captured by buccaneers in 1687, she turns them into pirate hunters to seek out and destroy their pirate lord in return for the location of a great treasure. Commanding El Cazador, she is known by her English and French crew as Lady Sin and Captain Sin. She appears on the cover of Issue 5 (March 2004) in an homage to Pyle’s Picturesque Buccaneer. My many thanks to Antón Viejo Alonso for reminding me of this comic book cover!

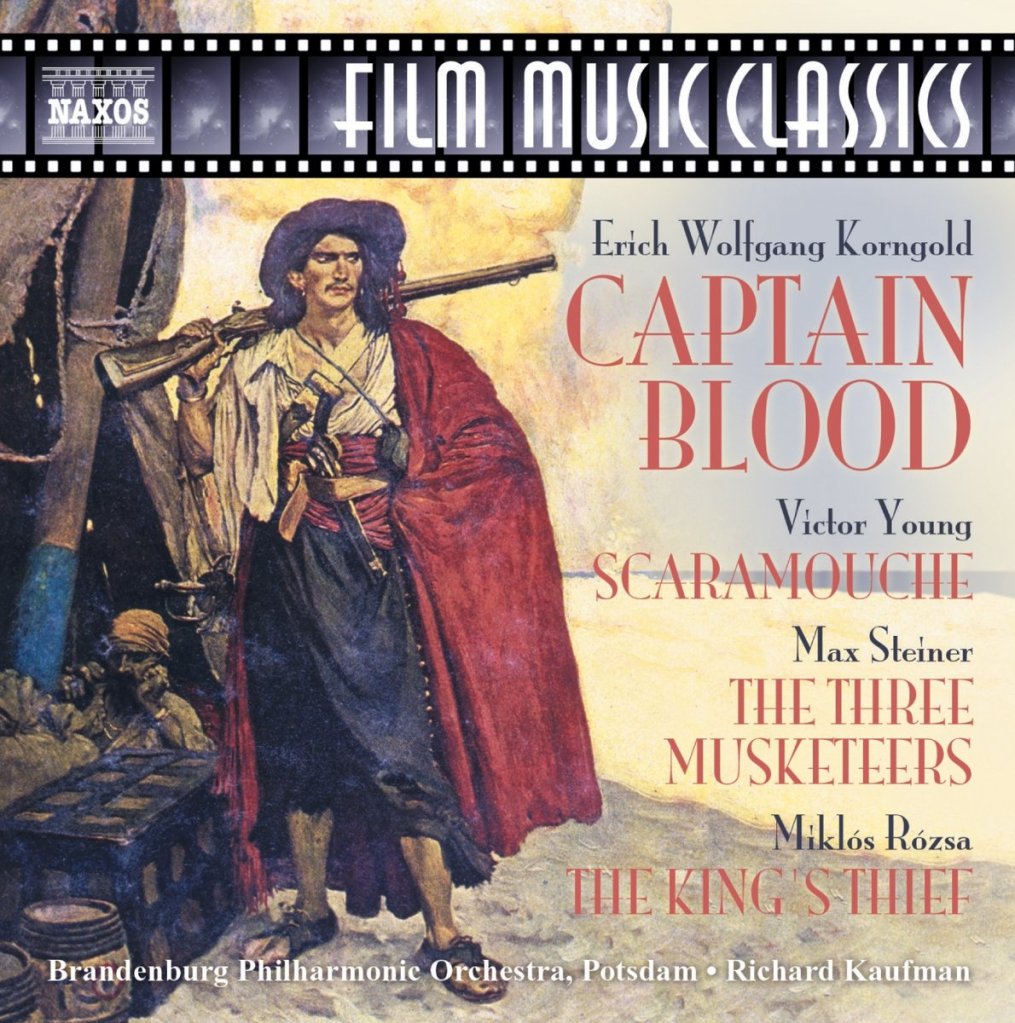

The Naxos re-release of these film music classics by the Brandenburg Philharmonic Orchestra uses the picturesque buccaneer on the “album” cover, albeit reversed. Good music too!

Firelock Games created a special edition figure as an homage to Howard Pyle for its popular (and quite historically accurate) Blood & Plunder tabletop wargame. (Full disclosure: I’ve done quite a bit of consulting for Firelock Games.)

Even produce growers, or at least one of them, have appropriated the swashbuckling image…

Perhaps the most significant homage to Pyle’s painting came from another great illustrator: Norman Rockwell. But Rockwell’s buccaneer is no longer the youthful adventurer with a touch of arrogance, but a tired grizzled veteran with torn cloak and shirt, a sash of a different color, a hat that has long lost its tassels, and a leg lost to a broadside, yet who keeps sailing the Main with his buccaneer brethren even as he begins to long for home. There are a few anachronisms, as there always are in such paintings: his pistol is of a later era, as is the cutlass that has replaced his rapier, and his boots are entirely fanciful and unhistorical — pirates didn’t wear any such footwear. But I find no real fault with such details. As I said, these are evocative, not historical images.

But I do find fault with the home Rockwell has the buccaneer dream of, for it evokes Olde England as N. C. Wyeth might have painted it — perhaps even the Admiral Benbow Inn! — and not Spanish America. I imagine our Spanish renegade buccaneer, young and old, longing instead for a place along the Spanish Main: Campeche or Veracruz, Havana or Matanzas, Puerto Bello or Maracaibo. Or perhaps he’s even from Spain! But no matter: he has chosen to sail with the hated buccaneers, and might never see his home or family again. But let us remember that these are only paintings, only part of the story: we might fill and finish the buccaneer’s tale as we please.

Copyright Benerson Little 2022. First posted August 17, 2022. Last modified March 6, 2023.

Captain Blood, Not Jack Sparrow: The Real Origin of Disney’s Wicked Wench Pirate Ship

It’s an epic image, one that anyone who’s ever cruised through the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction at one of the Disney theme parks is familiar with: a pirate ship cannonading — “firing its guns at” or “engaging” in sea parlance — a Spanish fort.

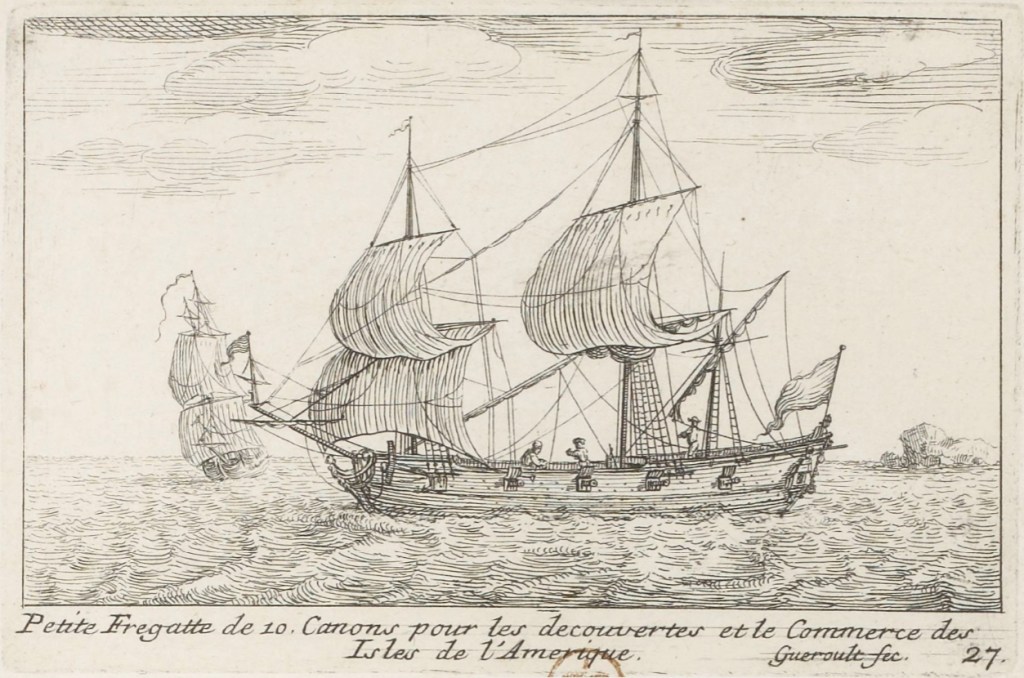

But the image-in-motion long predates the Disney attraction. In fact, as I’ll demonstrate shortly, the entire scene was lifted directly from Rafael Sabatini’s famous novel, Captain Blood: His Odyssey and especially from the 1935 film version starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone. And the Wicked Wench pirate ship of the attraction was more than simply inspired by the Cinco Llagas / Arabella, as the ship in the novel and film was named: it was copied from it!

Originally the attraction depicted buccaneers in the second half of the 17th century attacking and sacking a Spanish town on the Main. “IN THE CROSS FIRE of cannonades between pirate ship and Caribbean port,” begins the caption of the 1968 Disney publicity still of the Wicked Wench shown above. It continues with “this crew of Disneyland adventurers sail through Pirates of the Caribbean as grape shot and cannonballs land around them. The pirate captain on his bridge gives the signal for an eight gun salute. The scene of one of ten action-packed segments in the thoroughly realistic re-creation of buccaneer days.” For now I’ll pass on correcting Disney’s descriptive language, as some readers might misconstrue such revisions as nautical pedantry.

However, in spite of the obvious historical basis for the ride’s inspiration, according to Disney’s modern Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise “canon” the Wicked Wench was instead the ship that would become the Black Pearl commanded by Jack Sparrow et al, more or less, post-buccaneer era. Not a buccaneer ship, in other words, but a later ship turned to pirate ship as would fly the Jolly Roger. This, of course, is nothing more than mere revisionism for the sake of marketing the ride on the coattails of the film series, and any “canon” (as in nearly all franchises) is nothing more than the result of a series of screenwriters trying to write popular scripts, and fans subsequently trying to make rabid sense of their details and many loose ends.

Myself, I much prefer the original orientation of the attraction, liberties taken with real buccaneer history notwithstanding. That said, comic ride though it may be (and one that I thoroughly enjoy), it does get some things right, including torture, pillage, and burning, not to mention the original implication of some scenes now altered from their original. We have, in fact, two versions of piracy in our culture: factual history and popular myth, the latter often overwhelming the former.

And now for the evidence that the Wicked Wench is really the Cinco Llagas / Arabella!

The Scene of Ship Attacking Fort Was Inspired by & Lifted Largely From the 1935 Film

One need only to watch the 1935 Captain Blood to confirm this. The only difference between the two is that the roles are reversed: rather than a Spanish pirate attacking the principal town of an English colony in the late 17th century as in the Rafael Sabatini novel and the film based on it, buccaneers in the attraction attack a Spanish town, as they often successfully did — and far, far more often than Spanish pirates did against English, French, and Dutch colonies.

In fact, in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Black Pearl there is an homage to the pirate attack in the 1935 film version of Captain Blood: some of the shots of locals running for cover are quite similar to those in Captain Blood.

For more details on the ship-versus-Spanish fort trope, see “The Iconic “Spanish” Fort: Only a Spanish Galleon Says “Pirates” Better!“

The battle depicted in the Disney ride, and by derivation the one in Captain Blood, was given an homage in The Curse of Monkey Island (LucasArts, 1997).

The Wicked Wench is Red Like the Cinco Llagas / Arabella of the Novel

According to Rafael Sabatini, who clearly emphasized the sanguinary nature of buccaneering via the hero’s name and other thematic elements, the color of Peter Blood’s pirate ship was red. However, red was not an exceptionally common color of ships at the time. Red paint was typically used for the bulwarks (the inner “walls”), gun carriages, and often some fittings of men-of-war, and some other ships as well, at the time, and the upper works (the upper outside of the hull) and sterns of some ships were occasionally painted red — but never the entire hull. However, the application of pine tar, tallow, and linseed oil could lend a reddish hue to hull planking (particularly to those ships built of various “mahoganies” in the Americas), but this would not cause a ship to be referred to as red. (Far more details on the possible appearance of the Cinco Llagas / Arabella are forthcoming in Treasure Light Press’s annotated Captain Blood.)

And the Wicked Wench? A red ship, of course!

The Profiles of the Wicked Wench and the Cinco Llagas / Arabella are Too Similar to be Coincidental

Indeed! The similarity is obvious when comparing the images below. Even the scrollwork on the stern upper works is almost identical (see the image above and also at the end of this section). Disney did make some alterations to suit the attraction, including reducing the ship from two decks to one, and, of course, making it small enough to fit in the attraction.

And Then There’s the Names of the Ships…

After its capture by a handful of renegade rebels-convict led by Dr. Peter Blood, the Cinco Llagas was renamed the Arabella after the woman Blood loved but thought he could never have. Arabella Bishop, although independent, strong-willed, and anything but swooning (or languishingly voluptuous!), was still a lady in manners and mores, unlikely to (sadly!) run away to sea in men’s clothes with Peter Blood. One can easily see a tongue-in-cheek homage to Arabella and the Arabella in the renaming of the Spanish frigate as the Wicked Wench, and even in the “Woman in Red” in the old Bride Auction scene on the attraction.

Likewise the captain of the Wicked Wench as an inverted homage: no clean-shaven gentleman buccaneer he, unlike Captain Peter Blood, but bearded and beribboned like Blackbeard the Pirate and bellowing in G-rated curses like Robert Newton or Peter Ustinov in their piratical film roles. That is, before Hector Barbossa took his place to align with the film franchise. (N.B. Blackbeard was not a buccaneer but a later black flag pirate, and although most buccaneers appeared to have been clean-shaven, some French boucaniers, and therefore buccaneers, did wear beards.)

For more details on “The Woman in Red,” now “Redd the Pirate,” (and in any case, an anthropomorphism of the ship by both), see “The Women in Red: The Evolution of a Pirate Trope.” For more details on the black flag — the so-called Rackham flag with skull and crossed cutlasses — flown by the Wicked Wench, see “The Fanciful, Mythical “Calico Jack Rackham” Pirate Flag.” Note that on the Disney LP featuring a narrated soundtrack of the ride, the Wicked Wench is referred to as the Black Mariah, the name of the ship in “Donald Finds Pirate Gold!” Perhaps Wicked Wench was suitable on the stern but not in narration at the time on an LP likely to be listened to mostly by children?

So, Was the Wicked Wench Really the Arabella?

Only Disney knows — and only Disney can answer how the Arabella, sunk among the cays just off Port Royal, Jamaica in 1689 while defending the town from French attack, came to be raised, refitted, and ended up again in buccaneer, then pirate, hands… 🙂

And the Black Pearl?

If you’re looking for the real original inspiration for the Black Pearl, discard any notion of it having been the Wicked Wench — this is probably just “canon after the fact.” Convenient revisionism for the sake of marketing, in other words. Sparrow’s famous ship is more likely inspired ultimately by Tom Leach’s 40-gun Black Swan, from Sabatini’s novel of the same title. Or at the very least it corresponds closely to Sabatini’s description of the ship, including its black hull. Even the un-authorized plastic model of Sparrow’s Black Pearl is sold under the name of the Black Swan. Are there similarities between the Wicked Wench and the Black Pearl? Of course there are. Clearly the set designers took a look at the Wicked Wench, but it is much closer to the Arabella. (By the way, the duel in The Black Swan is described here.)

And for you budding “nautical pedants” out there, here’s the correction to the Disney text quoted above: “this crew of Disneyland adventurers [an acceptable term: French buccaneers aka flibustiers were often referred to as adventurers] sail through Pirates of the Caribbean as grape shot [this form of small shot was in its early development and generally not known by this name at this time] and cannonballs [more correctly, round shot] land [splash] around them. The pirate captain on his bridge [quarterdeck, not bridge] gives the signal for an eight gun salute [a correct humorous euphemism for a broadside]. The scene of one of ten action-packed segments in the thoroughly [and humorous] realistic re-creation of buccaneer days [a statement more correct than it might appear at first]…”

Post Script: The Wicked Wench is Not the Only Disney Pirate Ship Inspired By an Errol Flynn Film…

Disney’s Jolly Roger, from the animated version of Peter Pan (1953), bears a striking resemblance to the Albatross from The Sea Hawk (1940, directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Errol Flynn). 🙂

Copyright Benerson Little 2022-2024. First posted June 22, 2022. Last updated February 9, 2024.

Pirate Pulp Fiction Paperback Cover Art!

For fun!

I’m not going to pretend to write a pretentious analysis of pop cover art and imagined social implications, nor any other nonsense. I’m neither an art historian nor inclined to see things that aren’t really there. Suffice it to say that these covers are intended to be eye-catching, often titillating, and always bordering on near-lurid, entirely to lure potential readers to buy the book. The accompanying cover copy, the blurb especially, is almost as over the top as the art. This isn’t a criticism, for similar art and copy is often found on the covers of far more notable works.

As for the text inside? Suffice it to say that it’s not comparable, in spite of the cover copy claims, to that of Rafael Sabatini or any other notable writer of romantic adventure. Pirate pulps are almost always extremely light on literary substance and historical accuracy, and quite heavy on cliché. Trope writing in other words. Sheer fantasy in the sense of “never happened.” Pure swashbuckling pirate genre in the form of the twentieth century version of dime novels. Enjoy!

Copyright Benerson Little, 2021 – 2022. First posted May 20, 2021. Last updated May 9, 2023.

The Romance of Swordplay: Some Favorite Images

Originally I’d intended to write a post entitled, “Whither Modern Fencing?” and illustrate it with some of my favorite inspirational fencing images. However, the likelihood of the subject turning into a lengthy near-rant was too strong, particularly if the draft of the first few paragraphs was any indication, so in the end I’ve decided to let the images speak for themselves. The accompanying commentary may be read or ignored according the reader’s inclination. Enjoy.

1. Untitled by Aaron Siskend, from “The Most Crowded Block”

Quite possibly my favorite swordplay image other than personal ones of friends and family fencing, and if not my most favorite, then surely one of my top three. The swashbuckling adventure of youth, exactly what swordplay should always be at any age!

The lure of fencing is to fight with swords, not to participate in mere sport, at least not for most of us drawn to fencing. We want to fight one-on-one for honor, for romance, for the clash of steel-on-steel. We want to sword-fight for fun, for adventure, and, importantly, for the “All for one and one for all!” camaraderie fencing in the right circumstances can bring. These days, the purely sport mentality of too many fencing coaches, administrators, and parents often misses this fundamental truth. To paraphrase my first fencing master, Dr. Francis Zold, “Fencing is not sport: fencing is swordplay!”*

At the end of a lecture I gave in 2020, or perhaps the year before–has it been that long?–on the history and practice of modern Western swordplay for a local continuing education program whose students were mostly retired persons, several came up afterward and, pointing to the photograph above which was still showing on the projection screen, excitedly and animatedly agreed that it conveyed exactly how they felt about fencing, even to depicting how they themselves had played at “sword-fighting” in their childhoods.

For what it’s worth, during the two-hour practical sessions on the following two weekends, these retirees proved to be some of the most apt pupils I’ve ever had, learning far more quickly and easily than much younger students. Many had wanted to learn to fence since they were kids but had never had the opportunity. Life can make dreams difficult to come true, but this is no reason to stop dreaming, much less stop trying to make them come true.

And if you can do nothing else, improvise some swords and let your inner swashbuckler take over, no matter your age!

2. Douglas Fairbanks Fencing With Kids on the Set of The Three Musketeers

Evocative not only of the silent film era swashbuckler, but also of children’s fascination with swashbuckling heroes, then and now. Who of these children would not today still tell the story of he once fenced with Fairbanks as d’Artagnan! Fairbanks created the modern swashbuckler film genre, with its over-the-top tongue-in-cheek antics, best described–other than by viewing!–in the following New York Times review of The Three Musketeers, August 29, 1921:

“For here, plainly, is a D’Artagnan that not even Dumas ever dreamed of. He is the personification of all the dashing and slashing men of Gascony that ever fought their way through French novels, all for the smile of a lady. He never fences one man if there are six to fence instead, he never leaves a room by the door if there is a window or a roof handy, he never walks around any object (including human beings) if he can jump over them; he scales walls at a bound, carries prostrate damsels over roofs, hurls men one upon another, rides no horse save at a gallop, responds to the call gallantry at the drop of a hat, and general makes himself an incomparable D’Artagnan.”

A perfect description of our four-year-old, almost five now, son, too. 🙂

I still recall my first fencing master, Dr. Francis Zold, telling me how Fairbanks and his entourage came to watch the Hungarians in the final round of the saber fencing at the 1932 Olympic Games, and saw Gyorgi Piller (one of my fencing “grandfathers,” in fact) win the gold. A few days before the Hungarians had been invited to Picfair, the famous eighteen acre estate he shared with his wife, Mary Pickford, for a large Olympic Games dinner party which featured two hundred invited guests including Charlie Chaplan, Clark Gable, and Constance Bennett.

3. The Duel Between Peter Blood & the Villain Levasseur in Captain Blood, 1935

What a difficult choice from among the wonderful publicity stills of this duel! It remains my favorite film swordfight by far: it’s from the best film version of my favorite novel of youth (and still one of my favorite books, so much so that we’re publishing an annotated edition): it’s a pirate duel on the beach; it’s for the hand of one’s beloved (although not so in the novel); the villain, Basil Rathbone, deserved to be run through for his gaudy French accent (nothing personal, Rathbone, you’re one of my favorite villains and Sherlocks, and you actually could fence well); the duel is wonderfully choreographed; and even the accompanying music is great, although Erich Wolfgang Korngold was upset that he didn’t have time to compose it himself, and was forced to use Liszt’s Prometheus at the last minute. Last, Three Arch Bay near Laguna Beach, California, here made up to look like a Caribbean island, reminds me fondly of my many days spent on Southern California beaches in my youth and as a young Navy SEAL officer.

It is films like these, and novels like those written by Rafael Sabatini and his like (Sabatini wrote Captain Blood: His Odyssey) that inspired many of us to become fencers. They also inspired a number of true swashbuckling swordsmen and swordswomen of real-life adventure, the majority of whom from the early to mid-twentieth century have already passed away, and there are sadly far too few replacements.

Just as sad, the number of true swashbuckling fencer-writers is severely diminished. Even so, I’m happy to see a few today who are following in their adventurous footsteps. “Books are good enough in their own way but they are a mighty bloodless substitute for life,” as Robert Louis Stevenson wrote in his excellent essay of advice on life, “An Apology for Idlers.” Likewise with movies and television too. Why not “take a walk on the wild side” and pick up both pen and sword as you head out the door for real adventure?

I’ve even written four of a planned five (or six or even seven?) blog posts on The Duel on the Beach, greatly inspired by this duel and the one in Rafael Sabatini’s novel, The Black Swan. Here’s the first of the series: “The Duel on the Beach, Part I: In Fiction.” Links to the rest can be found here as well.

4. “Dreams of Glory: Captain Blood” by William Steig.

This comic came to my attention only recently, and by accident. It captures entirely not only my youthful (and not so youthful) dreams of glory, and that of many others I know. By William Steig, best-known as the author and illustrator of Shrek, it is part of a series of “Dreams of Glory” comics published in upscale magazines some seventy years ago. What dreams we had — and many of us still have!

5. Famed Fencing Master Fred Cavens Training Binnie Barnes for The Spanish Main

One of the last great pirate swashbucklers before the genre descended into B-movie purgatory (arguably almost elevated again to A-level status by the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, although the overweening element of fantasy disqualifies the films in my opinion), The Spanish Main’s best swordplay was not that of the star, Paul Henreid as Capt. Laurent Van Horn (combining the names of two real Dutch buccaneers, Laurens de Graff and Nicolas Vanhorn who actually fought a duel on Isla Sacrificios), but of his adversary Paul Emery as Capt. Mario du Billar, and equally that of Binnie Barnes as the anachronistic Anne Bonney. To this day I recall the first time I saw a passata soto: Binnie Barnes executed one in this film.

Fencing master Fred Cavens and his contemporaries, along with those who followed, gave us the film swordfights that have imprinted themselves indelibly on our swashbuckling psyches. Although swordswomen were in the minority, and still are, in swashbuckling films (actual history itself unfortunately tends to preclude sword-armed women except in rare circumstances), their were several worthy ones in this era, and often their swordplay was as good, or better than, the best of the male actors: Maureen O’Hara, Binnie Barnes, and Jean Peters all did superbly creditable fencing scenes. Reportedly, Bebe Daniels was a masterful swordswoman in Senorita (1927) playing a Zorro-like character, but only two prints of the film exist and apparently neither has been digitally transferred. Not surprisingly, Cavens trained all four of these women actor-fencers and choreographed their swordfights.

And Fred, or formally, Frédéric Adolphe, Cavens? He set the standard for sword choreography in film, largely unmatched these days although through the first decade of the 21st century his descendants followed worthily in his footsteps (or rather, footwork?). And for a fact there are sword choreographers and fight directors today who can arrange exciting swordfights that evoke a sense of the reality of swordplay–if only their directors would let them.

6. The Climactic Duel in The Spanish Main

I honestly can’t claim that this image from The Spanish Main (see image and notes above) is one of my absolute favorites, but it perfectly illustrates more than one swashbuckling trope, and, more important to me, I recall complaining excitedly to one of my fencing masters, Dr. Eugene Hamori, when I was nineteen years old that John Emery on the left above (though doubtless I didn’t recall his name at the time) was a much better swordsman than Paul Henreid on the right–but he had to lose! It bothered me as a fencer that a skilled swordsman must ignore so many tempo opportunities with which to skewer–to pink, to use the 17th century expression–his adversary. But scripts are scripts for a reason and far more “winners” of Hollywood duels were inferior fencers as compared to their adversaries. I’ve been unable to find anything out about where Emery learned to fence, unfortunately.

The tropes? There’s the swooning or near-swooning heroine watching two men duel to the death, although not always over her; the swordfight in the dungeon (similar tropes are the duel on the beach already noted in this post, and the swordfight in the tavern); and, above all, the duel to the death between hero and villain, often but not always at the climax.

Readers will notice one thing in common with many of these images: the fencers are often in an en garde position with swords crossed, or more correctly, with blades engaged. Inaccurately, fencers are often in a modern sixte guard rather than the much more historically accurate tierce, a reflection of their modern training. Notably, John Emery is en garde in tierce, not the usual modern sixte as his adversary is, although Emery’s tierce is probably that of saber, not historical smallsword. But no matter, it’s surprisingly correct for a genre swashbuckler.

7. Maureen O’Hara Engaging the Cardinal’s Guards in At Sword’s Point

Yet again, a difficult choice among a number of swashbuckling film stills of Maureen O’Hara, one of classic Hollywood’s greats. Here she comes en garde against several of the Cardinal’s Guards. She does a credible job taking a fencing lesson early in the film, and holds her own with the male lead, Hungarian-born Cornel Wilde who was not only a US National Champion in saber fencing, but also was selected to the US Olympic Fencing Team–until he chose to take a stage role instead!

Here O’Hara fences in riding boots, that costume accessory–“fetishwear,” a UK journalist described it–so alluring to painters, writers, and costume designers of swashbuckling flare. Here at least it’s historically accurate, for she had been riding. But if her boots are as stiff as those of the cavalry, she won’t be able to move well. In fact, cavalrymen dismounted in action would often abandon their boots in order to make their escape afoot, for the boots hindered running to an extreme degree.

O’Hara also thrusts and parries in the 1952 film with Errol Flynn, Against All Flags, really a B-level pirate flick but still fun and still better than most of the B pirate genre. Women running around with swords, women as pirate captains, women as erstwhile musketeers is nothing new in fiction or film, although some would have us believe this today. If anything, the older films–Against All Flags, The Spanish Main, At Sword’s Point, Anne of the Indies, among others–have more redoubtable women sword-adventurers than many films do these days (although some video games have rectified this in that medium). Admittedly, though, there is an unfortunate tendency for the sword-bearing female lead to either give it all up for love, and by implication, marriage, or to die unrequited so that the male protagonist can marry his true love, naturally non-sword-wielding and often demure and largely obedient to her husband-lord-and-master. I prefer independent sword-wielding women myself. I married one, after all.

8. Jean Peters in Anne of the Indies, 1951

One of a pair of well-posed publicity stills showcasing Jean Peters engaged against Blackbeard the Pirate. It’s a favorite of mine, one of three common poses in images like this: blades crossed, or one adversary attacking while one parries, or one adversary running the other through. I’m torn between the two, the other showing Peters running Blackbeard through. But this one shows her spirit better, I think.

Jean Peters, known not only for her films but, in popular star worship and gossip, for her marriage to Howard Hughes, for which she left her short but notable acting career behind, plays Anne Providence, really Anne Bonny, or at least Anne Bonny as imagined in the popular mind. I remain both astounded and bored senseless with the mindlessness with which novelists, playwriters, and filmmakers continue to elevate Anne Bonny over Mary Read, assuming anything Charles Johnson wrote about them is actually true, for most of what he wrote about the two women cannot be verified. But even if partly true, why runaway girlfriend Anne Bonny over the martial Mary Read? Anne Bonny as described by Charles Johnson’s account makes her a dilettante along for a brief piratical joyride. But, if the account has any merit, Mary Read had been a soldier and fighting seaman in disguise as a man. Yet it’s Bonny who gets all the attention, which says much about what readers and viewers are interested in. A few more details on the subject can be found in The Women in Red: The Evolution of a Pirate Trope.

The film, in spite of its many pirate clichés and bad Hollywood history, is still quite enjoyable and often more serious than the usual pirate film. But it’s the swordplay I enjoy most, brief as it is, or perhaps second most–the fierce female pirate captain remains a favorite. Peters is as good as any of her male contemporaries when fencing Blackbeard with sharps in a tavern duel, more or less, a common trope albeit probably not one in reality. Brawling in taverns, sure, even murder in taverns, but dueling was typically conducted outdoors and out of sight.

Her duel is one of the better film affrays with swords, even if Blackbeard is stoutly barrel-chested rather than tall and lean as he was in reality, and even if both adversaries are wearing those damn Hollywood boots. Peters carries off her swordplay with élan and well-focused cold-blooded anger, which can actually be quite useful for a fencer. Hot blooded anger often has poor results, but cold blooded fury can lead to victory.

As an aside regarding Howard Hughes, Disney’s film The Rocketeer portrays a Howard Hughes-like character, along with a swashbuckling actor-swordsman based on Errol Flynn and unfounded rumors that he was a Nazi sympathizer.

9. D’Artagnan and the Three Musketeers in the Eponymous Film, 1974

Yes, I know it’s not an image of swordplay per se, but it perfectly captures not only the camaraderie of fencers but also the moment these musketeers bond immediately prior to their fictionally famous combat against the Cardinal’s Guards. This 1973-74 film ranks high among the best, in my opinion, of The Three Musketeers and related films. It and its second part, The Four Musketeers, both starring Michael York, Raquel Welch, Oliver Reed, Richard Chamberlain, et al, rank among the finest and is hands-down my favorite. I saw them when they first arrived in theaters in Los Angeles, well, Northridge to be precise, in a twin theater in the local mall. And nothing excited me more than at the end of the first to see a teaser for the continuation! (It’s not a true sequel, the film was cut into two parts due to length, for which the actors rightfully sought and got more money.)

York was perfect at the young swashbuckler d’Artagnan. Reed was probably playing himself as Athos, a perfect fit. Chamberlain was, I believe, starring in a Shakespeare play (Richard III?) I saw in the sixth grade in Seattle a half century ago, although it might have been his understudy. (“It’s Dr. Kildare!” the girls, and probably a teacher or two, gushed as we stood in line.) Decades later I saw him starring in Spamalot. (“Run away! Run away!” I still joke from the film to beginning fencers when teaching them that the retreat is their first line of defense after a good en garde.) Frank Finlay as Porthos was far too short (the character, based on Dumas’s father, was a giant) but certainly had the right attitude, and Raquel Welch was surprisingly good as Constance. Faye Dunaway was perfectly alluring, cold, and frightening as Milady de Winter. And the Cardinal? Like Reed, I imagine Charlton Heston was playing a bit of himself in the role, and flawlessly. Last, the swordplay, if often inauthentic (novelist and screenwriter George MacDonald Fraser admitted this to me in a letter) was well-choreographed by William Hobbs and perfectly suited the mood of the film. Yes, Hobbs was perfectly capable of historically accurate choreography, just watch The Duellists, it’s the gold standard.

The 1935 version of The Three Musketeers, starring Walter Abel and Paul Lucas, is also quite creditable. The aforenoted notable Fred Cavens choreographed the swordplay, with a young Ralph Faulkner doubling some scenes. Faulkner would go on to become one of Hollywood’s leading fencing choreographers, largely succeeding the retiring Cavens. Faulkner was still teaching in Los Angeles in the late 70s when I first learned to fence: in his 90s, I believe, his legs and eyesight failing, he taught admirable lessons from a chair, and was the inspiration and early master of at least one Hollywood fencer-choreographer gentleman I’m acquainted with. Sadly, I never was able to get away to get a lesson from Faulkner, if only to say I’d had one.

The 1939 comedy-drama version of The Three Musketeers with Don Ameche, Binnie Barnes (previously noted in The Spanish Main), and the Ritz Brothers is quite good as well, the Ritz faction providing laughs even while staying true to the core of the story. There were laughs in the 1973-1974 version by director Richard Lester and novelist-screenwriter George MacDonald Fraser as well, although these two films cannot be classified as comedies. I have great fondness for Douglas Fairbanks’s 1921 version (see photo above), given its role in helping create the modern Musketeer genre, and similarly for the 1948 overwhelmingly much too bright Technicolor with almost gaudy stage costumes version starring Gene Kelly, mostly because it was played at the Pacific Coast NCAA fencing banquet in Los Angeles in 1978, in old school fashion with a 16mm projector set up in the room.

I still to this day can’t bring myself to watch most, perhaps all, of the modern film and TV versions, spoiled as most are by a juvenile brat pack mentality or by hyper-exaggerated melodrama, not to mention their steampunk- and video game-inspired costumes. (Will swashbuckling costume designers ever return to historical accuracy, not that it’s often been a priority anyway?) And, frankly, the swordplay is usually terrible as well, both in authenticity and, worse perhaps, basic choreography.

While on the subject, I should add the two most notable film versions of Cyrano de Bergerac, given that Cyrano is a cadet in a guards company, much akin to the musketeers of the King and Cardinal (in fact, there are even a series of novels by Paul Feval fils placing Cyrano and d’Artagnan together): the 1950 version starring Jose Ferrer (in English) and the 1990 version, which I first saw in a small theater in La Jolla, California, starring Gerard Depardieu (in French). Both are outstanding versions of the play, each with its own style. I might prefer the French version just a touch more than English, but it’s a difficult choice to make.

One day I want to watch the play from a box, as Cyrano does in the play. And like Cyrano, I’ll be sorely tempted to call down to the stage if the acting is bad, although this was in fact just a pretext for the large-nosed swordsman. A duel on the stage and grounds immediately afterward would complete the daydream. For fans of the play or films based on it, try Cyrano, My Love (Cyrano, Mon Amour), its a comedy in the vein of Shakespeare in Love (that is, not historically accurate but enjoyable to watch) about Edmond Rostand writing his famous play. As of the original date of this post, it’s streaming on Amazon Prime. Also check out Roxanne starring Steve Martin and Daryl Hannah: the swordplay, of tennis racquet versus golf club, in well-choreographed and enjoyable.

10. Obi-Wan Kenobi Versus Darth Vader in Star Wars, 1977

I first saw this film in the summer I graduated from high school. I’d seen the full page color ads in the Sunday LA Times entertainment section, and was already well-enticed. A substitute teacher saw it the week it was out and his description, something to effect of “Entertaining if lightweight, generally pretty cool” only increased my desire to see it. And it did not disappoint, at least not to a seventeen-soon to be eighteen-year-old romantic adventurer in the making.

I don’t recall where I saw it the first time, either in San Diego, California or Huntsville, Alabama. I saw it once or twice again that fall of 1977 at the long-since demolished Plitt Twin Theaters in Century City, LA, with its, for the time, state of the art sound system: you could hear the sounds of Vader’s ship above as it docked, just as the defending soldiers look up in the film. Already fans in the theater had lightsabers that lit up slowly from hilt to tip as in the film, which gives some idea of the effect on pop culture the film was already having. I was entranced with the film! It was, and remains, escapism at its best.

All this said, as enjoyable as the film was and is (and to hell with Lucas for not releasing the original version on Blu-ray, but instead the updated version with awful added special effects), I’ve never regarded it as anything more than what it really is: a space opera, which is nothing more than a Western set in outer space. It’s the updated version of the Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials–Westerns in space–from the 1930s I watched as TV reruns when I was around eleven years old. The science of Star Wars is bad, the tactics are ludicrous (suicidal on all sides), the dialogue in any other setting often silly or even cringeworthy. Didn’t Harrison Ford tell Lucas something to the effect of, “You can write this sh*t but you can’t say it!”? Still, I suppose it’s better than the modern dull suburban party conversation, as a journalist acquaintance put it, that passes for dialogue in costume TV and film these days (and in too many historical novels too).

So, not for me arguments over canon, which is in any case nonsense given how popular films and sequels are written (on the fly, to maximize profit, and to some degree to satisfy or gratify egos), or whether which sequels are great and which terrible, or misogynistic whining about any of the versions celebrating women. I’m a fan of strong women, therefore of the last three of the series, not to mention that our five-year-old sees his mother as the sword-fighting Rey. I could add a rant here about sexism in action films and their audiences, but there are plenty of writers who’ve already done it better.

I could also rant at length about the idea of the “hero’s journey” given that I find it unrealistic: the ideal Joseph Campbell gives us, and which influenced Star Wars, or so I hear, gives us villains as well as true heroes. Further, in my experience this is not how heroes and heroism are made. The hero’s journey is a device of fiction, not fact. It may make for good storytelling, but it also helps prop up autocrats of all sorts, including the worst of them. After all, to their supporters they’re heroes whose hero’s journey validates their autocracy and other misdeeds.

But back to swordplay! In the film it’s pure well-choreographed Hollywood, but no matter: the swords and swordplay are flawed fantasy that match the film well. And the idea of the old master facing his student is something of a trope too, but it’s done well in this film, if not quite so in the sequels, even given the mystical silliness of the Force. For me, I was soon introduced to someone who might be a real Jedi master, in the form of my first fencing master whose adventures and escapades could rival those of Obi-Wan Kenobi–and Dr. Zold’s were real. Likewise those of my second fencing master, Dr. Hamori. Mysticism and magic swords are always appealing but it’s long study, practical ability, and character, plus a good dose of good Fortune, that really make the difference in swordplay, and for that matter, life.

Today, modern “Olympic” fencing in the US and France, and probably other places, have showcased “lightsaber” fencing to some degree, primarily as a recruiting lure. Modern fencing, as noted above, has forgotten why most fencers want to fence. Star Wars and its fans have not. Modern fencing needs a strong return to its swashbuckling roots, although I’m cynical about the prospect. I don’t like the term “Olympic fencing” but it’s apt, for the FIE (the international governing body), not to mention USA Fencing, will do almost anything to keep fencing in the Olympic Games, even if it means turning fencing into little more than a game of audience-friendly tag. If fencing or any sport can’t draw an audience–pay the bills–it’s out. And the governing bodies are unwilling at any cost to lose the cachet–and money–that being an Olympic sport brings, sadly.

The best that can be said of the swordplay of the Star Wars franchise is that it’s exciting to watch and, importantly, inspires swashbucklers as once the old costume historical swashbucklers did (and still do for those who watch them). For this alone it can be forgiven its flaws.

11. The Duel on the Cliffs in The Princess Bride

There’s no need to describe this image, nor even the accompanying dialogue, so well is this film known among romantics and swordplay enthusiasts. I doubt any of the hundreds of beginning fencers I’ve taught in more than twenty years have not recognized any reference I’ve made to the film. (And for that matter, to Monty Python and the Hold Grail, too.)

No, the dialogue references to fencing masters don’t actually reflect the swordplay of the moment, and yes, it’s all entirely Hollywood fencing. But it’s beautiful Hollywood cinematic swordplay! Perfect for a fantasy film. I’m still hopeful to see–even influence or have control over–historically accurate swordplay in remakes of some of my favorite films, but such accuracy is not required for all films.

As for fencing left-handed? (If you’re reading this blog and haven’t seen the film you’re probably an unlikely exception, but to help you out, the dialogue associated with the film above refers to left-handed fencing. “I’m not left-handed either…”) There are a number of reasons to learn to fence with the off or non-dominant hand. Foremost, it helps keep the body balanced. Fencing is a notoriously one-sided sport, with obvious imbalances in strength and flexibility that develop within a year or two. Spending a third to half of one’s time fencing opposite-handed will prevent this, for the most part. Second, it helps “rewire” your nervous system, creating new pathways. A more balanced body and mind, in other words. Third, if your dominant hand or arm is injured, you can easily switch to the other side while healing, short-term or long-term. Last, if you ever become a fencing teacher, it will enable you to give lessons with either hand to the benefit of your students. The downside? It limits your practice with your dominant hand, with which most fencers prefer. And it may take a few years before you become near-equally proficient with your non-dominant hand/side.

Most importantly, you can join the ranks–indeed, the trope–of ambidextrous fencers! I’ve only known one truly ambidextrous fencer (Dr. Ted Cotton of Loyola University in New Orleans, he’d wear two gloves and choose which hand to fence with based on which might prove stronger against his adversary at the time), and only a few who could fence nearly as well with the offhand as with the dominant.

12. Swordplay in Le Bourgeois Gentilehomme

There’s probably far more choreographed swordplay in the theater than in film, simply due to volume, but we seldom recall theatrical swordplay the way we do film swordplay, no matter how well done–and often it’s quite excellent. Like the theater itself, theatrical swordplay tends to be highly stylized, with larger, slower actions the audience can follow.

A few years ago when my wife and I visited my old master, Dr. Eugene Hamori, in Budapest, he took us to an outdoor performance of Hamlet by the Royal Shakespeare Company on Margit Island. Subtitles–or rather, overtitles?–were in Hungarian, although most Hungarians in the audience probably spoke English. That said, Shakespeare is difficult for most native speakers, and usually frustratingly obscure to English as a second language (or third or fourth) speakers. Only Americans seem to hold the arrogant position that one need ever know only one language. We were a bit disappointed in the duel in the final act, for it was over far too quickly. Perhaps as fencers we expected more, perhaps we were conditioned by the Laurence Olivier film version to expect more. Still, it was an enjoyable evening. By chance we also ran into Kristina Nagy, a noted HEMA longsword and modern saber fencer, during intermission. Only a day or so before she had shown us around the famous fencing salle at Semmelweis University.

The image above, illustrating the fencing scene (Act III, scene 3) between M. Jourdain and Nicole the maid in a nineteenth century production of Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilehomme (1670) is a favorite of mine not because it illustrates stage swordplay, but because it captures Molière’s satire on swordplay (and of course, the bourgeoisie) in general. A few lessons do not a fencer make, much less a combat swordsman or swordswoman capable of effective swordplay in duel or battle. Further, arrogance can lead to defeat, can even be fatal were the swords sharp. Here, M. Jourdain is easily hit by Nicole. I’ve seen a lot of fencers fall victim to the “magic sword” fallacy: a few small victories and they forget that fencing requires patience and focus always. You can’t just walk out and wave your sword around and expect it alone to hit your adversary or achieve your victories just because you believe you’re more skilled. “But I’m better than he is!” is one plaintive excuse I’ve often heard from losers, along with, “But I take so many lessons a week from so and so!” (FYI, you don’t need that many lessons.)

In fencing as in warfare arrogance can be fatal. A single mistake is enough. An old SEAL Master Chief I worked with at SEAL Team THREE used to say that, “Even a toothless old man sitting in an outhouse and armed only with an old muzzleloader can still kill you if you’re not careful.” And that “ignorant” with a sword? Beware, for he or she is likely to ignore all the conventions you’ve been taught to expect–and hit you in spite of all your lessons, skill, and previous successes.

Francisco de Quevedo has a similar hilarious scene in his picaresque novel Historia de la Vida del Buscón, Llamado Don Pablos, in which a student of La Verdadera Destreza (The True Art: Baroque swordplay insufferably infused with geometric circles and other esoterica unnecessary to the teaching of swordplay but much beloved by those seeking “secret knowledge”), with his angles and arcs, is comically defeated by a soldier lacking in the true art. Quevedo himself, one of Spain’s greatest literary icons and treasures, was a proponent of the Destreza Común, or common swordplay. Quevedo once humiliated Don Luis Pacheco y Narvaez, the leading master at the time of the school of La Verdadera Destreza, in a duel: with his rapier he removed Narvaez’s hat.

An end note on the play: many years ago I would disparage the patronizing use of “Bourgeois” by social elites, including in the play which is nonetheless quite funny. I found the attitude offensive: I don’t believe in social castes, including the nobility de facto or merely perceived. Today, after decades of dealing with certain elements of the middle and upper middle class–many of whose members are socially elitist, the American bourgeois, so to speak–, I’m much less sympathetic, equal now to my antipathy toward all social elites and social climbers. That you’re the “Director of Pomposity at Such and Such Corporation” has no bearing on how I’ll regard your behavior or your teenager as a fencing student, nor will it make your teenager a better fencer–or you a better person. There is a positive side to such bourgeois behavior, however: the comic relief is never-ending. Or, put another way, a wonderful font of material for a writer.

13, 14, 15, & 15a. Three by Howard Pyle

Here I simply couldn’t choose only one of Howard Pyle’s famous paintings of swordplay, so well do they depict swordplay not only in the popular mind, but often in the my mind of fencers themselves. For those of us who grew up on swashbucklers, they evoke how we see ourselves. Pyle’s influence on swashbuckling film, including pirate films, is enormous. His iconic images are imitated even today.

The scenes are similar: one adversary lunging, the other parrying, easily the most evocative of fencing actions, and easily posed, even if fencers seldom look so good. Spectators are inevitably in the background, although many duels were fought without witnesses in the late 17th century. We imagine the Dominican friar kept largely quiet during the duel in the first image (in fact, he tried to stab John Blumer in the back after the duel), likewise the gentlemen in the second which has a rather unusual arrangement for the era, more typical of duels in the late 19th century in Pyle’s era. Would pirates have kept silent during a duel? We don’t know, in spite of all my research into the subject of piracy. The only similar duel was between the aforementioned Dutchmen and was over so quickly that it’s unlikely anyone had to time to say much of anything. We do know that in the late 17th and early 18th century some public duels, particularly among soldiers, had noisy spectators: some chided Donald McBane for retreating so much. His retort was to imagine what they’d do in his place.

Until recently, anything more than polite applause from spectators, and silence from fencing masters or coaches, was mandatory in fencing. Today it’s often noisily noisome. Spectator comments are distracting to both fencers, as for that matter is coaching, not to mention that coaching also informs the adversary, not just the coach’s student, and flies in the face of the tradition that fencing should be a single combat between fencers alone.

Of course, fencers remain forbidden to talk to each other during a fencing bout, although often they do in fiction and film, and should–at least if the dialogue is well-written!

The story accompanying the first image does have fairly detailed swordplay, as does the third. The first, “In the Second April,” is apparently set in the late 18th century although the historical allusions the author tosses about are eclectic and often anachronistic or fanciful. The story opens with a reference to a 1670 treaty as if it has just been signed, then transitions to references to George Guelph, who might be George I, II, or III. John Bulmer–the Duke of Ormskirk–claims to have studied under late 18th century fencing master Angelo, then tells his adversary that he is clearly of the school of Boisrobert, strong in attack but weak in parry. (A possible inspiration for the exchange in The Princess Bride?) Boisrobert (also Bois-Robert) and Berthelot are two fencing masters named by Alexandre Dumas in Sylvandire, a romance set during the reign of Louis XIV, and also in Le Chevalier d’Harmental (co-authored with Auguste Maquet) set in 1718. In the latter romance a character is recommended to change fencing masters, giving up Berthelot for Boisrobert, with accompanying advice on giving ground when necessary and parrying in time, suggesting an emphasis, French school-wise, on parrying. James Branch Cabell more or less reversed the teaching of the fencing masters. Boisrobert and Berthelot appear in no records of fencing masters I have reviewed.

16. The Duel on the Beach by N. C. Wyeth

Perhaps the most evocative image of imagined pirate swordplay, in particular the duel on the beach. Given that I’ve already written an extensive blog post about this image and the story and book it illustrates (The Duel on the Beach, Part II: The Black Swan), I’ll keep my comments short. So much a favorite of mine is it, that I’ve a copy on canvas nicely framed. The image above is taken from the short story that soon afterward was turned into the novel The Black Swan by Rafael Sabatini. The painting was not commissioned for the story, however.

In spite of its historical inaccuracies, I can’t imagine a more romantic image of swordplay!

Now, on to a few historical images…

17. A Pass in Tierce, with the Unarmed Hand Used for Opposition, Late 17th Century

I’m including a sample or a few of my favorite historical fencing images, although again there are far too many to post them all. Up first is perhaps my most favorite, or at least is tied for the top three, that of a pass made while thrusting in tierce while using the unarmed hand to oppose the adversary’s blade. The thrust was probably preceded by a bind in tierce. The reality of swordplay is that the unarmed hand should be brought into play to minimize the possibility of an “exchanged thrust” or double touch, notwithstanding the argument of many masters of the past two to three centuries that the sword alone is sufficient to both attack and defend. But enough of technical issues.

Beyond its swashbuckling imagery, I particularly like that the fencer on the left is black, for black fencers were far more common than is generally known. I even wrote an article for American Fencing magazine on the subject some years ago, “The Black Fencer in Western Swordplay (Spring, 2011).” The scarf on the black fencer’s head is typical of a gentleman when not wearing a wig, and not, as some have suggested, an indication in this instance of piracy or African culture. The fencer on the right is a fop, easily discovered by the comb fashionably tucked in his wig, and perhaps by the two pigtails of his wig as well. Both men have discarded their scabbards in order to fence more unencumbered, although their rencontre is clearly hasty enough that they have not discarded their coats. Or perhaps they hope their coats will prove a bit of protection against thrusts. Certainly it was advised to keep one’s coat on when engaged with an adversary armed with a cutting sword.

The image is one of a number in a series by Marcellus Laroon, a Dutch artist in London who was proud of the scars he bore from his own dueling. He’s best know for an exceptional series of detailed images of the working London poor, The Cries of London.

18. A Duel Somewhere in France, by Louis François du Bouchet circa 1670.

For two or more decades this classic swashbuckling image churned quietly in my fencing subconscious until one day recently I realized, as I was rereading The Black Swan by Rafael Sabatini, that it quite probably inspired the scene for the duel on the beach in the finale. I even wrote a blog post about it, “The Duel on the Beach, Part II: The Black Swan.”

The drawing is by Louis François du Bouchet, marquis de Sourches (1645 – 1716), circa 1670. Bouchet is best known for his Mémoires du marquis de Sourches sur le règne de Louis XIV, publiés par le comte de Cosnac et Arthur Bertrand (Paris: Hachette, 1882-1893).

If nothing else, the image provides the wishful swashbuckler with hours of inspiration in swordplay, including imagining exactly what the two swordsmen are doing. I’ve discussed this elsewhere, but the extreme position of the sword-hand of the swordsman on the right strongly suggest an attempted angulation (cavé) after being parried, although the hand in supination (quarte) would be more common and more functional in most cases, although a bit slower going from full pronation to full supination. Of course, we assume they’re swordsmen: perhaps one is a pre-Mlle. La Maupin, the famed opera singer and duelist…

19. The Fencing Master, late 17th Century

Although as little as ten percent of a fencer’s development might be laid at the feet of the fencing master (this point was originally made to me by noted fencing master Kaj Czarnecki in 1980), it is a critical ten percent that lays the foundation for everything else, including independence on the strip, and, ideally, in life. Many of my fondest fencing memories are of lessons in which I was taught not only technique, but also tempo, tactics, strategy, patience, perseverance, focus, and strength of will. Lessons from my masters, Dr. Francis Zold and Dr. Eugene Hamori, also advanced my already romantic swashbuckling inclinations. Rafael Sabatini captured the romance of the fencing lesson in Scaramouche (1921):

“From a room beyond, the door of which was closed, came the stamping of feet, the click and slither of steel upon steel, and dominating these sounds a vibrant, sonorous voice speaking a language that was certainly French; but such French as is never heard outside a fencing-school. “Coulez! Mais, coulez donc!…So! Now the flanconnade—en carte…And here is the riposte… Let us begin again. Come! The ward of tierce… Make the coupé, and then the quinte par dessus les armes… O, mais allongez! Allongez! Allez au fond!” the voice cried in expostulation. “Come, that was better.” The blades ceased.”

It’s little different today, at least in traditional clubs and salles.

The French fencing master above is wearing a padded (with horsehair, probably) leather plastron to prevent bruising from repeated thrusts. One may fence for hours with scarce a bruise, but a student hitting the same spot repeatedly during the same exercise will bruise even the thickest skin eventually, often sooner than later. His shirt is tied at his waist, outside of his breeches rather than being tucked inside, probably so the shirt doesn’t ride up. Both hands are gloved, possibly for giving lessons with either hand, but certainly for protecting the off-hand when using it to parry or oppose. His shoes are of a sort used by fencers and masters for at least two and a half centuries: the toe of the lead shoe is open to prevent jamming or bruising the toes or toenails when lunging (a problem even today if shoes are ill-fitting and the floor has a good grip). Likewise the thick short socks worn over the stockings are to prevent blisters and other injuries to the feet. In the master’s pocket is a handkerchief, its use obvious. His wig, or possibly hair, is tied at the nape of the neck to keep it out of the way. Hats were often worn while fencing indoors, and were formally doffed and donned as part of the salute. Note that sword saluting was a practice only of the fencing salle, not of the duel, or at least not among the French and those who followed their practices.

20. A German Salle d’Escrime

An 18th century exhibition in a German fencing salle. It captures much of the allure of swordplay, and more than hints at the sound of blade on blade. My blood has always quickened with excitement at that sound, especially when heard from a distance. There is no other like it! The entire atmosphere of a fencing club is electric. In fact, parry strongly enough or get hit hard enough on your mask, and you’ll even smell ozone.

Multiple weapons are at play in the image: long- or great sword, smallsword, sword and dagger, German dusack, halberd, and quarterstaff. Given the directors or marshals (aka referees in modern fencing parlance), it is clearly a competition. The boxes and grandstands are filled with spectators, and there’s even a drummer, probably to assist with announcements such as the beginning and ending of bouts. Notably, there are no fencing masks, which would not come into regular use until the 19th century. Some of the participants are taking refreshment. Such a display today is more akin to a HEMA (Historical European Martial Arts), sometimes known as WMA (Western Martial Arts, whose name cynics claim was created by North Americans so they wouldn’t feel left out) tournament, with its broad variety of historical weapons, even if the greatest focus is on the longsword. Frankly, although HEMA is still sorting itself out (and learning that a lot of things, competitions and judging, for example, are not as easy as its members originally thought, and that the theoretical and practical foundations of modern fencing are actually quite sound), its participants seem to be having a lot more fun than many modern fencers who tend to take themselves and their sport far too seriously. O parents! Why must you spoil swordplay for your children! Perhaps that’s the key: parents seem largely absent from HEMA, at least by comparison to modern Olympic fencing…

21. A Family of Fencers

A family, certainly, the likely father holding a rapier or transitional rapier, the boy holding a dagger or toy sword, the mother holding a set of keys. Does she fence too? I hope so. As much as I love fencing and teaching fencing, I’ve probably had as much or more fun fencing for fun with my four children over many years, particularly when they’re little and fully embrace the swashbuckling fun of swordplay. And my wife? The best bouts I’ve ever fenced were with her. One went eleven minutes of intense fencing before the first touch (she got it). Club members stopped fencing to watch! The FIE be damned: fencing doesn’t need a touch or more per minute to be interesting.* It just needs bouts consisting of focused fencing that leads to moments of furious fencing. How many touches are scored is immaterial. The anticipation of touches alone is far more alluring to audiences than attempts to force fencers to score quickly. Ah, “what fools these mortals be!” Or certainly some of them.

*A relatively new rule penalizes fencers during direct elimination bouts if a touch isn’t made within each minute. The rule is almost universally loathed. It was created to force fencers to be more aggressive, epee fencers especially, on the theory that aggressive fencing is more likely to draw the audience fencing needs to remain an Olympic sport. Frankly, the IOC is ruining sports and sport. Think the IOC isn’t all about money? Just take a look at its attitude toward the Tokyo Olympic Games during the pandemic, last summer and at present. Why do sports put up with this? Money, prestige, and, to paraphrase Casanova, most people are feckless when push comes to shove.

22. Women Gladiators, 17th Century

A painting I enjoy because it shows women gladiators, or duelists, or fencers (depending on the interpretation), and because my wife and I saw it in the Prado, an art museum that should not be missed by anyone visiting Madrid. Women have fenced and otherwise fought with swords not only for centuries, but likely millennia. Surely Atalanta, or at least the women who inspired her creation, fought with a sword at times on the voyage of the Argo!

What the painting depicts remains up for debate. Early interpretations suggest a rendering of the famous 1552 duel in Naples between Isabella de Carazi and Diambra de Petinella. Later analysis suggests this to be unlikely. Another theory is that the painting is an allegory of the conflict between Spain and Naples. Another theory is that it is an allegory of “Counter-Reformation feminine virtue over courtly vice.” The Prado considers it most likely that the work was part of series of paintings depicting scenes of the ancient world. Women gladiators were relatively common in ancient Rome, after all. The Prado has a second 17th century painting with the same title, Combate de Mujeres, attributed to Andrea Vaccaro, for the the History of Rome series for the Buen Retiro Palace in Madrid.

23. Sport Epee a Century or So Ago

Another image I’ve done a blog post on, so I’ll likewise keep my comments short. Why one of my favorites? Because it shows that little actually ever changes in fencing or in life. Criticisms of modern fencing notwithstanding, epee of more than a century ago looked a lot like it does today. And the drawings–caricatures–are so accurate they make me laugh. “Plus ça change…” See “Sport Epee Humor” for more details and translations, including comments that might otherwise go here.

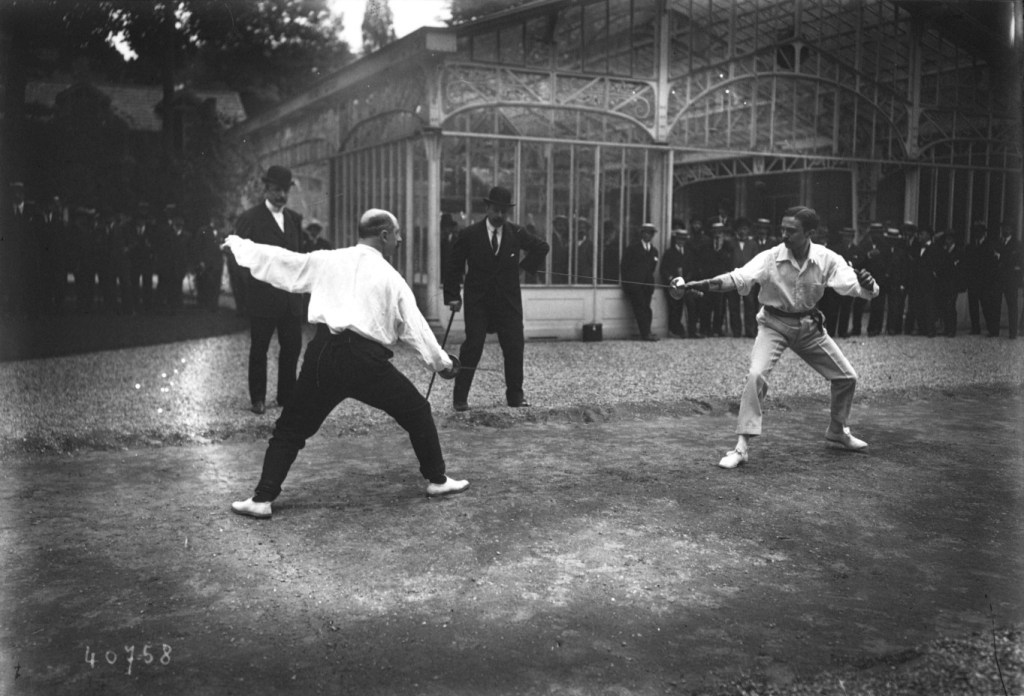

24. Le Duel Guillou-Lacroix, 1914

Dueling, the origin and foundation of modern competitive fencing (even if modern fencing is in the process of forgetting this) and the inspiration for most stage and film sword combat, not to mention much of our swashbuckling dreams, is really, or was really, an absurd practice that proved little more that the courage to engage in single combat. A critic once pointed out that the most common soldier in combat faced more dangers and proved to be of far greater courage. Nonetheless the practice of dueling persisted for centuries and the romance of dueling still persists.

In reality most fencers never fought a duel even when the practice was prevalent, epee duels were often fought by men with little or no fencing experience, and most of the best duelists were not the best sport or “salle” fencers. Still, dueling still attracted a fair number of skilled swordsmen, and occasionally swordswomen, even among those considered rational and well-aware that the practice was ultimately a perverse one, my first fencing master included.

The photograph above is by far my favorite among images of real dueling. The tension is clear: these men are fighting with weapons capable of killing, even if they hope to avoid that end and settle the affair with a minor or wound or two, as epee fencing was largely designed to do. Both men are skilled fencers, yet, as is common in photographs of actual fencing, they don’t have the look of posed images of fencing technique.

The duelists are Robert Guillot (left) and René Lacroix, and the reason for the combat a “polemique de presse“–an opinion piece that attacked an individual or institution. Such writings were in fact the most common source of duels in the early twentieth century. This encounter was one of those almost joyously celebrated in the press: expert swordsmen; a large audience; famous fencers and fencing dignitaries in attendance, assisting, and officiating; and a lengthy duel exhibiting “sang-froid” and expert technique. One expert fencer in attendance claimed it was one of the most beautiful duels he had ever seen.

The duel lasted five reprises or periods, each apparently directed by a different directeur de combat. By the end of the third reprise, M. Lacroix had twice wounded M. Guillot in the arm. Even so, M. Guillot continued for two more reprises until, unable to hold his epee anymore, an end was called by the attending doctors. The technique of the duel was classic: counter-attacks, doublés, envelopments, esquives du bras, beat attacks, straight attacks, dérobements, and conventional parry-ripostes. If M. Guillot persisted in his low guard, it’s not surprising he was hit twice in the arm.

Most nobly, the duelists, in a practice that continues among a few of us in sport fencing today, used their left hands to point out their adversaries near misses where the point put a hole in the shirt or brushed the skin. Many fencers I find will not do this today, fearing to give their adversary any advantage. But it’s a noble practice indeed to point out how close your adversary came to hitting you, as it helps their fencing. “Plaqué!” one should shout when the adversary’s point hits flat, meaning, “Almost! You hit flat! Adjust your point control! Next time you’ll hit me!”

In many ways this duel epitomizes what many of us would like to see return in modern fencing: a wide variety of technique, a “hit and not get hit” mentality, and a strong sense of honor and fair play. In fact, most modern epee touches are double touches, even if the machine indicates only a single; the other touch is simply “late” but would in reality still make a wound. The tendency to turn swordplay into a game of tag rather than of “hitting and not getting hit” has been the bane of fencing for millennia.

25. New Orleans Nostalgia

I debated whether to include any personal images in this post, but in the end decided that a few are appropriate. If I regret not posting any in particular, it’s group photographs showing the strong camaraderie of fencing over more than four decades. Some of my best friends and best times have been associated with fencing. But group photographs in the context of this blog might be less meaningful except to those in them, so I’ve somewhat sadly omitted the images.