Home » Posts tagged 'Bartholomew Sharp'

Tag Archives: Bartholomew Sharp

The Myth of Sharp’s Buccaneers, the Wreck of the Santa Maria de la Consolación, and Isla de Muerto

February 13, 2019 11:14 am / 4 Comments on The Myth of Sharp’s Buccaneers, the Wreck of the Santa Maria de la Consolación, and Isla de Muerto

The account of events is easy to find on the Internet: while on her two thousand mile voyage along the Pacific coast of South America in the spring of 1681, the Spanish merchantman–possibly a galleon, but likely only in the sense that any Spanish treasure ship might be known as a galleon–Santa Maria de la Consolación was sighted by one or more pirate ships under the command of the notorious buccaneer Bartholomew Sharp.

The Consolación only barely escaped by slipping into Guayaquil Harbor, but in her haste she wrecked on Isla Santa Clara. The buccaneers came ashore and, furious that the treasure was lost, tortured several of the crew and beheaded two of them.

So notorious were the acts of the buccaneers, or so one version of the story goes, that the island became known as Isla de Muerto.

The story has almost everything Hollywood has led us to expect in a pirate story.

But there’s a problem with this tale, as is there is with much that evokes Hollywood expectations.

Almost none of it is true.

The Buccaneers & the Santa Maria de la Consolación

Yes, there was a shipwreck.

The Santa Maria de la Consolación did run aground and sink.

And yes, the Consolación’s captain, crew, and passengers had been concerned about the pirates in the region, and yes, the pirates were commanded by the famous Bartholomew Sharp, at least most of the time.

But that’s all the truth there is.

Neither Sharp nor any other pirates chased the ship, nor did they come ashore after the wreck, nor did they torture or behead any of the crew or passengers.

In fact, the captain, crew, and passengers of the Consolación never saw any pirates at all, much led fled from any unless you consider the definition to include their haste to complete their voyage in case they might see them.

Bartholomew Sharp and his ship the Trinity were far to windward at the time. Only two or three months later did he and his buccaneers even learn that the Consolación had been at sea, and conditions made it impossible to search for her even though the sea rovers were in the area of Guayaquil.

Time, distance, and other circumstances–Fortune–ensured that the Trinity would never cross paths with the Consolación. Nor would the buccaneers even learn of the shipwreck until long after she had wrecked.

According to buccaneer and author Basil Ringrose (1684):

“August 19 [1681]. This day our pilot [captured July 29, 1681 aboard the Spanish ship El Santo Rosario] told us that, since were to windward, a certain ship that was coming from Lima bound for Guayaquil ran ashore on Santa Clara, losing there in money to the value of 100,000 pieces-of-eight; which otherwise, peradventure, we might very fortunately have met with.”

In fact, the buccaneers had no great guns (cannon) aboard their flagship, the Trinity, while the Consolación had more than twenty of brass and iron. Unless the buccaneers could have boarded the treasure ship, the battle might easily gone to the Spanish.

Sharp’s voyage is by far the most well-documented of any buccaneer or pirate voyage in history, with some seven members writing full or partial accounts. Further, Spanish records quite thoroughly corroborate the buccaneer accounts, including dates and locations. There is no possibility of mistake: Sharp and his buccaneers never sighted the Consolación, much less chased her, much less abused her crew. Having written several books on the subject of piracy, including extensive research on the subject of Bartholomew Sharp, I’m in a pretty good position to know.

Of course, there may, however, have been a small number of buccaneers who might have been briefly in the area, but they never saw the Consolación either and in any case were in no shape to have chased or attacked her. They were sneaking their way back to the Isthmus of Darien after having “mutinied” and parted from Bartholomew Sharp, finding his behavior as a commander less than acceptable.

La Isla de Muerto

One of these “mutineers” (they really weren’t mutineers, for buccaneer articles permitted crew members to leave the crew, provided that they paid for their provisions) was William Dampier, soon to become famous for his travels and books. He did write about the wreck when, as a member of a buccaneer crew three years later, they hovered around Guayaquil.

According to Dampier, writing of 28 November 1684 in his A New Voyage Round the World, “It is reported by the Spaniards, that there is a very rich Wreck lies on the North-side of that Island [Santa Clara], not far from it; and that some of the Plate hath been taken up by one who came from Old-Spain, with a Patent from the King to fish in those Seas for Wrecks; but he dying, the Project ceased, and the Wreck still remains as he left it; only the Indians by stealth do sometimes take up some of it; and they might have taken up much more, if it were not the Cat-fish which swarms hereabouts.”

If we look at several of the Basil Ringrose and William Hack (or Hacke) charts of the Bay of Guayaquil, based on a captured Spanish derrotero, we learn that Isla Santa Clara was known as Isla de la Muerto not because there was a massacre there, but because it is shaped like “the corps of a man in a shroud.” Dampier also notes that “it appears like a dead Man stretched out in a Shroud.”

From this would derive not only the island’s nickname, but also the myth. An additional suggestion toward the myth may come from a line in a copy of another of Hack’s South Sea waggoners, shown in the image below. Sharp, however, never actually gave chase as attested by numerous buccaneer accounts and Spanish records.

In other words, the coins aren’t cursed Aztec treasure (wrong region anyway), or cursed by direct association with pirates who tortured the crew, or cursed at all unless you consider the coca chewing slave labor used in extracting the Potosí silver from the mines or in refining it with poisonous quicksilver.

Salvage Coins

And if there were no massacre, any marketing done to sell coins salvaged from the wreck is misleading. I own a few coins from the wreck and as I recall there were references to the massacre in the associated descriptions and apparently still are. Why does this matter? Because people buying the coins might want to know that, although there is a buccaneer association, it’s not as close as often advertised.

Yet the purported association lures buyers. In fact, some several or more years ago I purchased one of these wreck-salvaged pieces-of-eight from a reportedly reliable coin vendor on ebay as a memento. I’m not a big coin collector, and generally don’t care for salvage coins. Perhaps as few as two or three wrecks whose coins are available on the market have an indirect relationship to actual pirates or sea rovers, and most salvage coins are in poor shape as compared to many “land hoard” coins. I prefer coins that have been handled and used, not those that have lain for centuries at the bottom of the sea soon after being minted. In other words, I prefer coins with a long active history.

However, having written several times of Bartholomew Sharp and his South Sea buccaneers, I thought a coin or two from the wreck of the Santa Maria de la Consolación off Santa Clara Island in the Bay of Guayaquil would be in order, given its association with the South Sea buccaneers. I found a third one reasonably priced, from a reliable coin vendor with high ratings and thousands of transactions. The coin was not expensive, as eight reale pieces-of-eight go, and was priced in the lower end of the range. I did not examine it too closely before buying it, although I ran it past the images of forged pieces-of-eight on the Daniel Sedwick website. But when I received the coin I was perplexed. It appeared genuine, but there was no sea damage at all, nor did the coin match any description of any New World coin.

Eventually I appealed to Mr. Sedwick to evaluate the coin for me. The coin was genuine, as I thought, but was a common piece-of-eight minted in Spain, “Seville” as it was called by the English in America, and not one from the wreck of the Santa Maria. Further, as Mr. Sedwick pointed out to me in an email, upon close examination it was apparent that the certificate of authenticity had been forged. I hesitate to accuse the vendor I purchased it from of this, although as a professional he should have spotted it.

More curious, though, is what the certificate forger, not to mention criminal jackass, whoever he or she was, expected to get away with. Perhaps he or she intended to capitalize on the inexplicable (to me at least) preference for sea salvage coins over land hoard and circulated coins which are typically in much better shape, although not always. Whatever he or she intended, the coin’s pretended shipwreck status did nothing to increase its value. Comparable Spain-minted coins often go for more money than I paid for it. I lost nothing on the transaction except the coin as memento. Now it’s part of a display of three coins as examples of the three types of pieces-of-eight described by English merchants in the Americas: Mexico, Peru, and Seville, based on their origins.

Ebay is often criticized for failing to scrutinize its coin vendors enough, and buyers need to be careful when buying from anyone other than a highly reputable dealer who deals regularly in Spanish cobs. Mr. Sedwick’s book, The Practical Book of Cobs has good sections on buying coins and spotting fakes. Although an expensive book, readers should also review Sewall Menzel’s Cobs: Pieces of Eight and Treasure Coins–The Early Spanish American Mints and Their Coinages, 1536-1773. (However, I should note that as of the date of original publication of this post, even Mr. Sedwick’s page associated with this wreck incorrectly stated that the pirates tortured some of the survivors &c.)

A bit of advice: don’t simply accept any claims made on the Internet. Double-check them. Start with books on the subject, and especially look for citations. If there are no citations in an Internet article, or even a book, be highly suspicious. For that matter, be a bit suspicious even if there are. Check the citations: you might be surprised to learn how often citations don’t actually support the claim. (This is unfortunately true even in some PhD-level scholarship more often than it should be: most often it’s a deliberate omission or even outright deception by various academic ideologues.)

In the case of these coins, you’ll find not only that there really aren’t citations given at all to support the claims, but also that the descriptions are all very similar, often identical. In other words, they all have the ultimate incorrect source. And when you go looking for books to support the claim you won’t find any. So why hasn’t the story been changed, even though I’ve challenged it on the Internet for some years now, and in books as well? Even though no scholarly work on Sharp’s voyage mentions it? Even though the written accounts of the buccaneers themselves not only don’t mention it but dispute it?

Money.

The purported pirate association makes the coins more likely to sell, or so the thinking goes, and in some cases permits a higher price.

Still, none of the foregoing should devalue the coins as “pirate treasure,” including the fact that the buccaneers never chased the ship. Sharp’s voyage was epic, and these coins are what he was after. The Santa Maria de la Consolación, sailing alone, struggled to make it safely to port, in fear all the while of Sharp’s buccaneers. These coins are the closest pieces-of-eight readily available–and affordable–to what we would describe as “buccaneer treasure.”

Copyright Benerson Little 2019. First published February 13, 2019. Last updated April 5, 2019.

Of Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar Smoking Women

January 1, 2017 5:34 pm / 9 Comments on Of Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar Smoking Women

Classic romanticized buccaneers! The pirate captain and his woman ashore on a Caribbean island or an isolated part of the Main, perhaps to share plunder or while careening, or simply to celebrate the holiday. We can always count on Howard Pyle to make the romantic appeal to our imaginations. And indeed, buccaneers did celebrate Christmas (and probably smoked cigars on occasion too), as I discuss below.

“How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas,” Howard Pyle, Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899, a special two-page image suitable for framing. In fact, I have it matted and framed.

BUCCANEER CHRISTMAS & DOG FOR DINNER

We do have multiple brief accounts of one buccaneer Christmas. Buccaneers, like other Europeans and European-derived Christian peoples, did observe the holiday, far more often with raucous, inebriated celebration than with religious devotion.

William Dampier noted that the captains of salt ships at Saltudos, or Salt Tortuga–where the very real Dr. Henry Pitman, inspiration for Sabatini’s novel Captain Blood, His Odyssey, was marooned–were always well-supplied with rum, sugar, and lime juice for visiting “privateers,” the euphemism for buccaneers, as opposed to the term “pirates.” Piracy after all was a crime.

“I have seen above 20 Sail at a time in this Road come to lade Salt; and these Ships coming from some of the Caribbe Islands, are always well stored with Rum, Sugar and Lime-juice to make Punch, to hearten their Men when they are at work, getting and bringing aboard the Salt, and they commonly provide the more, in hopes to meet with Privateers, who resort hither in the aforesaid Months, purposely to keep a Christmas, as they call it; being sure to meet with Liquor enough to be merry with, and are very liberal to those that treat them.”

Clearly, a buccaneer Christmas at any time of the year was a drunk-fest.

Our most famous description of an actual buccaneer Christmas dates to 1681, during the final days of the South Sea voyage of Captain Bartholomew Sharp and his companions in arms, in plunder (often as wishful as real), and in debauchery.

Sharp, already having been deposed once as captain once during the voyage during a stay at Juan Fernandez Island, a stay which coincidentally began on Christmas Day. Now, at the end of the voyage and almost home, with numbers depleted by buccaneer desertions, accidents, and deaths in battle, with the remaining crew on short allowance, Sharp remained a divisive leader, not for the least reason that by gambling with his fellow buccaneers he had increased his profit by leaps and bounds, leaving some of his comrades with little profit during the course of a long bloody voyage–not the best way to show leadership by any means.

On December 7th, according to buccaneer surgeon Basil Ringrose (I almost wrote Rathbone!), “This day our worthy Commander, Captain Sharp, had very certain intelligence given him that on Christmas Day, which was now at hand, the company or at least a great part thereof, had a design to shoot him; he having appointed that day some time since to be merry. Hereupon he made us share the wine amongst us, being persuaded they would scarce attempt any such thing in their sobriety. The wine we shared fell out to three jars to each mess.”

Mess size varied, as did Spanish jar size. Five to seven to a mess was common, but could even have been as small as four men. Spanish wine jars often, but not always, held a Spanish arroba, roughly four and a quarter gallons. At 750 milliliters to a modern wine bottle, we do some simple math and find that each mess received the rough equivalent of slightly more than sixty-four modern bottles of wine per mess, to last eighteen days: or, three and a half bottles of wine per day per mess. This wine may have been stronger than what we’re familiar with. It might have been very similar to Peruvian wine fortified with modern Pisco, the latter of which is usually 80 proof when sold in the US, but I’m speculating here based on a description of some of the wine found by buccaneers on the Peruvian coast. (And no, I won’t touch the “Who first came up with Pisco–Peru or Chile?” argument. We’ll leave the swords and poniards sheathed for now.)

Buccaneer surgeon Basil Ringrose provided the details: “This day being Christmas day, for celebration of that great festival we killed yesterday in the evening a sow. This sow we had brought from the Gulf of Nicoya, being then a sucking-pig of three weeks old, more or less, but now weighted about fourscore-and-ten pounds. With this hog’s flesh we made our Christmas dinner, being the only flesh we had eaten ever since we turned away our prizes under the equinoctial and left the island of Plata. We had this day several flaws of wind and some rain…” The holiday was celebrated roughly in the latitude of Rio de Janeiro.

An Ossabaw Island pig long-descended from Spanish and Canary Island stock, perhaps quite similar to the buccaneers’ Christmas pig. (The Livestock Conservancy.)

“Cinghiale. Sanglier. Wildschwein. Keuler. Wild boar. Wildzwein.” A sanglier or wild boar as seen in Europe and the Caribbean from European stock. Sangliers were prized for their taste. 1879. (Rijksmuseum.)

Sharp himself is a bit more direct: “When to Solemnize that Festival as well as we could, we eat the only Hog we had left, drank some Jars of Wine, and made our selves as merry as we were able, which I did the rather that my Men might not Mutiny.”

How they seasoned the pig is not noted. Given that their only way at sea of cooking was in a copper kettle, they would have boiled the flesh rather than roasting it over coals and seasoning it with a pimentade of lime juice, salt, hot peppers (pimento, or chili peppers as we know it), probably allspice, and perhaps a black or similar common pepper, as was common. The seasoning would have been similar in the copper pot, assuming they had the ingredients. The buccaneers would have served it with coarse boiled cornmeal (imagine a coarse polenta or coarse yellow grits, the latter are hard to find anymore) seasoned with salt and manteca (pig lard), which had been their only fare since departing the isle of Plata.

However, diarist John Taylor who visited Jamaica in 1687 wrote that Sharp’s buccaneers also served dog for Christmas dinner:

“Soe that they killed one hog, which was all they had left, and a spanell dog which they bought of one of their quartermaster for 40 dollars, on Christmas Day for their dinner.”

Alas poor beast, alas man’s best friend! But Taylor was no eyewitness, he was just repeating what he had heard from local sources. There was in fact a dog, a little curly shaggy-coated canine, like that of a poodle. And, according to one buccaneer, John Cox, who was there, they did in fact eat him:

“When we took the two Barks at Nicoya, we had a little sucking Pigg in one of them, which we kept on Board ever since for our Christmas days Dinner, which now was grown to be a large Hogg; so we killed it for Dinner, but thinking it not enough for us all, we bought a Spaniel-Dogg of the Quarter-Master for forty pieces of eight, and killed him; so with the Hogg and the Dogg, we made a Feast, and we had some Wine left, which made us merry: This being the only think we had eaten that had blood in it since our departure from the Duke of York‘s Island.”

But no one’s memory is perfect. Did they in fact eat dog for Christmas dinner? Was Cox inspired to exaggerate based solely on the rhyme of Hogg and Dogg? Do we see the interfering hand of an editor trying to “sex up” the manuscript? Again Basil Ringrose comes to the rescue, writing of a day in late January, well after Christmas, just prior to making landfall in the Leeward Islands:

“On that day [January 26, 1682], therefore, a little Spanish shock-dog, which we had found in our last wine-prize taken under the equinoctial and had kept alive till now, was sold at the mast by public cry for 40 pieces-of-eight, his owner saying that all he could get for him should be spent upon the company at a public merriment. Our Commander, Captain Sharp, bought the dog, with intention to eat him, in case we did not see land very soon.”

The money raised was added to one hundred more pieces-of-eight that were left over from a previous sharing of plunder, in which the boatswain, carpenter, and quartermaster had refused to accept shares owing to some disagreement “with the sharers.” The coins were laid up, to be spent ashore in celebration of their return to the Caribbean from the South Sea.

Two days later the buccaneers sighted Barbados, but were scared off by the barge belonging to the English man-of-war Richmond lying at anchor Bridgetown harbor. Two days after that the buccaneers sent a canoe ashore at Antigua, or Antigo as they called it, and from here they went their separate ways.

So it was not a Christmas dog after all! Or was it? We hope it was part of no Christmas dinner except to have gnawed any scraps ravenous buccaneers may have cast his way. “Perros Ingleses!” we have heard Spaniards call the buccaneers, or at least buccaneer surgeon Alexandre Exquemelin said they did on one occasion, and surely in fact on many. But dog don’t eat dog, or so they say, and we hope, more from Ringrose and the buccaneer arrival at Antigua and not necessarily from common proverb, that Cox was wrong and that Sharp may have been mostly joking about eating the dog.

Mostly.

WITH A WILLING WOMAN IN A HAMMOCK

So, would buccaneers have celebrated Christmas as in Pyle’s image above? With a willing woman in a hammock, smoking a cigar? It’s a common image in fiction, that of a romance between a pirate and a lady on the seashore. We almost imagine this as the setting in the aftermath of The Black Swan by Rafael Sabatini, but when we recall the noble manner in which the romance unfolded, his gentlemanly behavior, her lady-like sensibilities, we can’t imagine Priscilla Harradine smoking a cigar. On the other hand, we recall her attraction to men of adventure and her propensity for slipping off to swim nude, and we think perhaps she might after all.

The cover of the 1947 Editorial Molino Argentina edition.

For the sake of romantic notions, combined with the fact of romantic relations between buccaneers and some women, I will forego a discussion of the often profoundly disturbing treatment of women by pirates at times, a fact often ignored or only hinted at it film. You may find these sordid details in The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths, and in other works as well.

Some, probably many, buccaneers were married but they did not take their wives, or their women in general for that matter, to sea with them, the one known exception being John Beare who took his woman, the daughter of a rum punch woman in Port Royal, to sea at least once dressed as a man. Accused of piracy by the English–and yes, he was in fact a pirate–he fled to Havana where he married his true love and began serving as a Spanish privateer, or, as the English would have it, a Spanish pirate. Perhaps Beare did celebrate a Christmas ashore while careening, his inamorata waiting languidly in a hammock.

We also have the example of Dutchman Jacobus (James) Marquess, or “Copas” [Cobus] for short, a buccaneer “lingusiter”–also known as a “truchman” or interpreter–in the South Sea with Bartholomew Sharp. Copas fell in love, or perhaps merely deeply in lust, with a “Mustees” Spanish woman at the island of El Cavallo while the buccaneers were ashore taking in water over the course of four days and three nights. Many of his companions worried that he was a turncoat who intended to betray them to the Spanish. A Native American boy also ran away while at the island, perhaps with Copas.

“[T]he woman lieing on borde one or two nights, was very familiar with one Copas a dutch a man, who formerly had saild with the Spaniards…but was mainly Inamoured with thiss women, makeing her severall presents of some Vallew,” wrote a buccaneer who is best identified as Edward Povey.

Not in a hammock, yet in a recumbent pose with hints of Venus rising from the waves. Inspired in part perhaps by Howard Pyle’s painting above and perhaps by Spitfire Stevens (Maureen O’Hara) in Against All Flags, and therefore by popular visions of Anne Bonny, the painting is likely ultimately inspired by the redhead that once was part of the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean attraction. The painting, which hangs in the bar in the California version of the ride, is entitled “A Portrait of Things to Come,” suggesting the redhead becomes a pirate after the “bride auction.” Disney Image.

Copas pretended to go hunting but deserted to her instead, leaving all but two hundred pieces-of-eight of his plunder behind–some 2,200 pieces of eight, plus jewels and other goods. He must truly have been in love, indeed! Or perhaps he thought he could sell his knowledge of the buccaneers to their enemies. Alas, this instance of buccaneer love did not occur over Christmas, but late in May, 1681.

Raveneau de Lussan, buccaneer author, wrote that during the occupation of Guayaquil by French flibustiers in 1687, he was almost seduced away by the “widow of the local treasurer,” who suggested they hide in the woods until the pirates were gone, and then they could marry and he would have “her husband’s office in addition to her own extensive holdings.” Quite an offer! But de Lussan turned it down, and again, this flibustier love did not occur over Christmas, but in April. Spring is the time for love, so it is said. Or perhaps just for mating.

If any buccaneers did take their wives or inamoratas with them to sea, I imagine it may have been some of the early flibustiers and boucaniers who did so with their “Amazon wives who could shoot and hunt well,” as one chronicler noted of them, supporting the expeditions and perhaps even participating in the assaults themselves.

CIGAR SMOKING WOMEN

But IF a buccaneer did have his woman with him at Christmas (and here I speak of buccaneers solely as men only because, although there may have been one or more women in disguise among them as actual crew members, to date we know of none–Jacquotte Delahaye is a 20th century fiction, and Anne Dieu-le-Veut was a wealthy shore-based widow, not a flibustière), might she have smoked a cigar?

To find an answer we must first know if people smoked cigars in the 17th century Caribbean or anywhere else for that matter. Many modern pirate researchers and reenactors decry as incorrect the cigar-smoking pirates in Black Sails, for example, and one even called me out–incorrectly–on the subject after he read the prologue to The Golden Age of Piracy.

We turn first to Jean-Baptist Labat, priest and also chronicler of the late 17th and early 18th century Caribbean for the answer:

“We do not use pipes in the Americas; the Spanish, Portuguese, many English and French, nearly all blacks, and all our Caribs smoke bouts [“ends”], or as the Spanish say, cigars… It is rare to find a Spaniard without his provision of cigars.”

(Notably, Labat mis-heard cigaro and wrote it as cigale, or cicada in French. His description of cigars is quite modern: six to seven pouces long, and five to six lignes in diameter, roughly six and a half to seven and a half inches long, and around half an inch in diameter.)

Detail from a Dutch print by Crispijn van de Passe, 1641, showing an imaginary English merchant’s wife with wine and tobacco. (Rijksmuseum.)

We turn next to buccaneer-surgeon and author Alexandre Exquemelin who preceded Labat. He writes in the French edition of his buccaneer book that in “America one uses very little snuff, but smokes much tobacco. From tobacco leaves…they make small rolls which the Spanish call cigarros and which they smoke without a pipe.”

So Spaniards and others smoked cigars. But did buccaneers? Most buccaneers were English, French, and Dutch, although there were many other peoples, nationalities, and ethnicities among them, including Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and other European origins, plus African, Native American, even Asian via Mexico via the Manila galleon, plus a variety of mixed races. They were, in other words, a variety of white, black, and brown of many origins. And there were Spanish pirates of course!

The English, French, and Dutch chewed tobacco or more commonly smoked it in pipes, small to medium bowl size among the English and French, large among the Dutch. White clay pipes were the most expensive and typically from England and the Netherlands; terracotta pipes were cheaper and often made locally; and wooden pipes were the cheapest (and doubtless the worst to smoke).

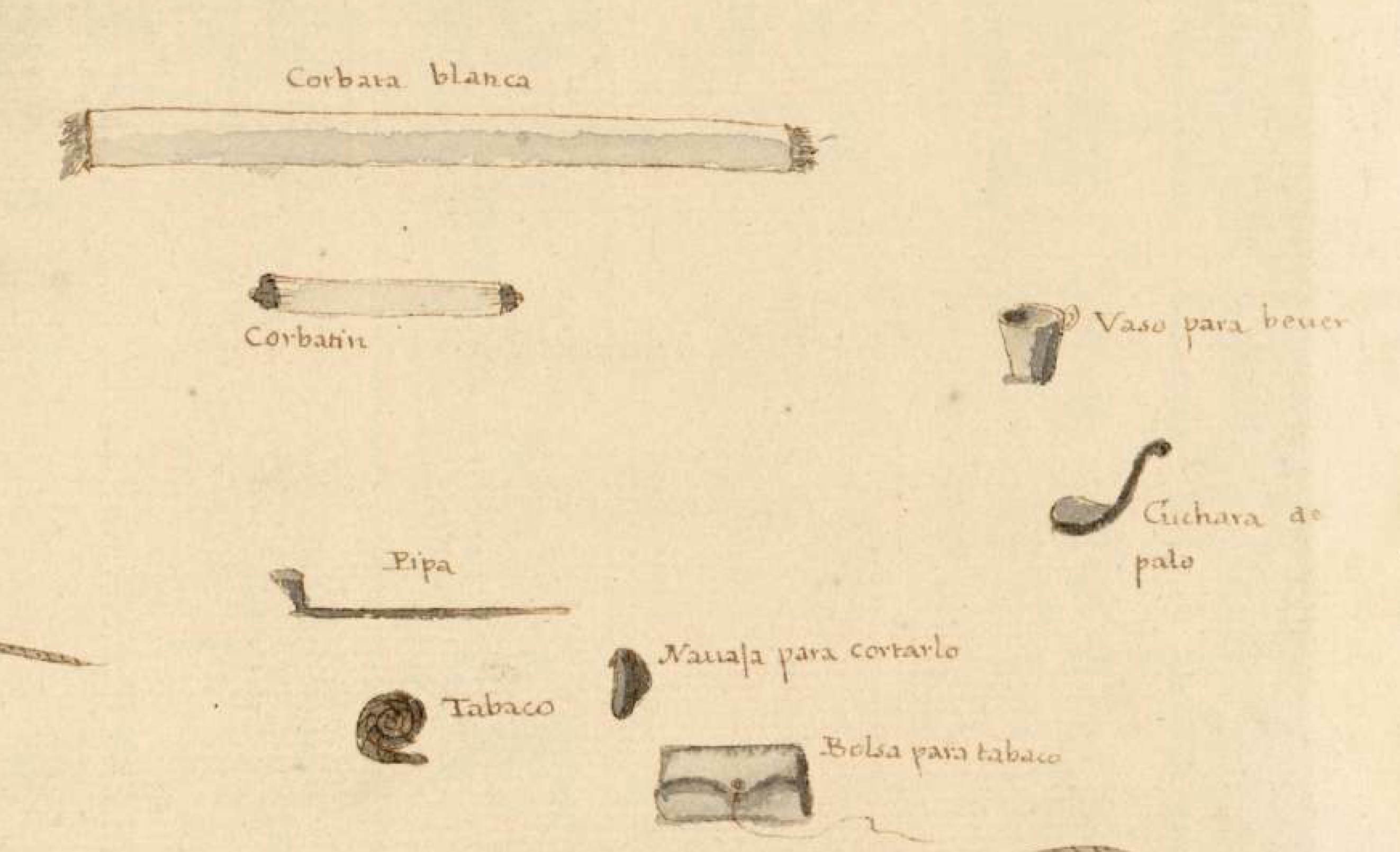

Some of the personal items of a typical Spanish naval officer in the first half of the 18th century, including a pipe, roll tobacco, a folding Navaja for cutting the roll, and a pouch for tobacco. Detail from the Álbum de Construcción Naval by Juan José Navarro de Viana y Búfalo, Marqués de la Victoria, circa 1719 to 1756.

Some of the personal items of a typical Spanish naval seaman in the first half of the 18th century, including pipes, cigars and roll tobacco, a folding pocket knife or Navaja for cutting the roll tobacco, and a pouch for tobacco and comb. Detail from the Álbum de Construcción Naval by Juan José Navarro de Viana y Búfalo, Marqués de la Victoria, circa 1719 to 1756.

However, Spanish buccaneers among them would likely have smoked cigars (or seegars as they became known among the English by the early 18th century), and some English, French, and Dutch may have preferred them at sea as they did ashore. Certainly some African slaves and former slaves among the buccaneers smoked cigars, and it’s probable that some English, French, and Dutch buccaneers smoked captured cigars, if only by cutting them up and smoking the tobacco in their pipes. There is no question that cigars were smoked at sea: the 18th century Spanish Álbum de Construcción Naval of the Marqués de la Victoria shows the cigar along with the pipe among the forms of tobacco used by Spanish seamen. Having smoked both pipe and cigar, I can say that a cigar is no more dangerous aboard a wooden ship than is a pipe: both can be hazardous if appropriate measures are not taken.

Ah, but did women smoke cigars? Well, we know that among the English, French, and Dutch many women smoked pipes, along with many African women in the Caribbean. And there were Native American women who smoked cigars. So why not Spanish women of any ethnicity? And why not cigars, given that they were the predominant means on the Spanish Main of taking tobacco? In fact, we know that in the 18th century there were Spanish creole women who smoked cigars, thus it’s almost certain they did in the 17th century as well.

Alexandre Exquemelin, the buccaneer-surgeon and buccaneer-author who gave us The Bucaniers of America, notes in his French edition that it was as unusual to see a Spanish woman in the Americas who didn’t smoke as it was to see a woman in France who did. (He also did not understand the allure of tobacco, for his medical experience had taught them that smoking was contrary to good health.)

Likewise John Cockburn, writing of the year 1735 in which he was captured by a Spanish guarda costa, or as the English would probably have it, a Spanish pirate, noted the following of three Spanish friars who had just crossed some mountains in Nicaragua:

“The gentlemen gave us some seegars to smoke, which they supposed would be very acceptable. These are leaves of tobacco rolled up in such a manner, that they serve both for a pipe and tobacco itself. These the ladies, as well as gentlemen, are very fond of smoaking; but indeed, they know no other way here, for there is no such thing as a tobacco-pipe throughout New Spain, but poor awkward tools used by the negroes and Indians.”

And who’s to say the woman in Pyle’s painting isn’t Spanish, after all? It is a romantic notion.

Of course, Pyle’s use of a woman smoking a cigar is even more provocative than merely putting her recumbent and languid in a hammock. Since the late seventeenth century, smoking in women has often been seen as a sign of promiscuity rather than as a notion of budding equality. But Pyle’s image is not merely a sexual provocation: it is an image of aggressive independence. This woman is no wallflower, she is no quiet being who fully accepts the purely feminine role imposed upon her. Rather, she is a suitable companion adventurer: a modern progressive woman even by the standards of Pyle’s day. I wouldn’t usually consider Howard Pyle as a feminist per se, but in this case I think he has already proved the argument.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cockburn, John. The Unfortunate Englishmen: or, a Faithful Narrative of the Distresses and Adventures of John Cockburn. “New edition.” London: Hamilton and Co. Shakespeare Library, 1794 (63-64).

[Cox, John]. The Voyages and Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, and Others, in the South Sea. London: P. A. Esq. [Philip Ayers], 1684.

de Lussan, Raveneau. Journal du Voyage Fait a la Mer de Sud, avec les les Flibustiers de l’Amerique en 1684. et Annés Suivantes. Paris: Jean Baptiste Coignard, 1690.

——. Journal of a Voyage into the South Seas in 1684 and the Following Years with the Filibusters. 1689. Reprint, translated and edited by Marguerite Eyer Wilbur. Cleveland: Arthur C. Clark Company, 1930.

——. Journal of a Voyage Made by the Freebooters into the South Sea, 1684, and in the Following Years. 1699. In The History of the Buccaneers of America by Alexandre Exquemelin [Joseph Exquemelin]. Reprint, Boston: Sanborn, Carter and Bazin, 1856.

——. Les Flibustiers de la Mer du Sud. 1695. Reprint, edited by Patrick Villiers. Paris: Éditions France-Empire, 1992.

[Dick, William]. “A Brief Account of Captain Sharp . . .” In The Buccaneers of America by Alexander Exquemelin [John Esquemeling], 257–83. 1684. Reprint, New York: Dorset, 1987.

Exquemelin, Alexandre [Alexander Olivier O’Exquemelin]. Histoire des Avanturiers Flibustiers qui se sont Signalez dans les Indes. 2 vols. Paris: Jacques Le Febvre, 1699. See also his 1686 edition.

Labat, Jean-Baptiste. Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l’Amerique. The Hague: P. Husson et al, 1724.

Lepers, Jean Baptiste. La Tragique Histoire des Flibustiers: Histoire de Saint-Domingue et de l’Ile de la Tortue, Repaires des Flibustiers, Écrite vers 1715 par le Rév. P. Lepers. Edited by Pierre-Bernard Berthelot. Paris: G. Crés, 1922.

Little, Benerson. The Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish Main, 1674–1688. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2007.

——. The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth About Pirate Myths. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016.

——. The Sea Rover’s Practice: Pirate Tactics and Techniques, 1630–1730. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005.

Navarro de Viana y Búfalo, Juan José. Álbum de Construcción Naval del Marqués de la Victoria. Museo Naval de Madrid.

[Povey, Edward?]. “The Buccaneers on the Isthmus and in the South Sea. 1680–1682.” In Jameson, Privateering and Piracy.

Pyle, Howard. How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas. An illustration in Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899.

Ringrose, Basil. “The Buccaneers of America: The Second Volume.” In Exquemelin, Buccaneers of America (Crooke, 1684).

——. Buccaneer Atlas: Basil Ringrose’s South Sea Waggoner. Edited by Derek Howse and Norman J. W. Thrower. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

——. “Captains Sharp, Coxon, Sawkins, and Others . . .” In The History of the Buccaneers of America by Alexander Exquemelin [Joseph Esquemeling], 180–313. 1699. Reprint, Boston: Sanborn, Carter and Bazin, 1856.

Sabatini, Rafael. The Black Swan. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1931.

Sharp, Bartholomew. Captain Sharp’s Journal of His Expedition. In A Collection of Original Voyages by William Hacke. 1699. Facsimile reprint, edited by Glyndwr Williams. New York: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 1993.

Taylor, John. Jamaica in 1687: The Taylor Manuscript at the National Library of Jamaica. Edited by David Buisseret. Kingston: University of West Indies Press, 2008.

Copyright Benerson Little 2017-2024. Last updated December 3, 2024.