Home » Posts tagged 'boucaniers'

Tag Archives: boucaniers

The Duel on the Beach, Part V: In Reality

If you’ve read any or all of parts I though IV of this series (In Fiction, In Film, in Rafael Sabatini’s novel The Black Swan, and of the duel between Flynn and Rathbone in Captain Blood, you might be wondering if novelists and Hollywood have depicted buccaneer and pirate duels, a common trope of the genre, accurately. Like much that is popular buccaneer and pirate image, the answer is “yes and no,” or more precisely, “sort of sometimes, but mostly no.” If anything, the duels imagined on page and screen have caught some of the spirit of historical buccaneer and pirate duels, rather than actual practice.

One thing we’re sure of is that the real duels probably did not look like those engaged in by the swordsmen in the plate above!

N. B. Besides the links above, more information about dueling, swordplay, and swords among sea rovers and mariners of the era in general can be found in Buccaneer Cutlasses: What We Know; in chapter 17 of The Buccaneer’s Realm; and in chapter 8 of The Golden Age of Piracy, which has more detail and analysis than is found in this post.

We know that buccaneers and pirates fought duels occasionally, although detailed accounts of individual duels, with an exception or two, do not exist. Further, we know even less about the tactics and techniques of individual duels. In fact, only rarely do we even know what weapons were used in specific duels. Often the description is as spare as, “Here it was that our quartermaster, James Chappel, and myself fought a duel together on shore,” as buccaneer-surgeon Basil Ringrose wrote.

And why were duels fought among buccaneers and pirates? For the same reason they’ve always been fought: usually out of some misguided form of honor, although doubtless there were occasionally good reasons to fight. The gamut of human emotion easily gave rise to duels: jealousy, envy, avarice, lust, deep-seated insecurity, narcissism, pride and its exaggeration hubris, competition, and more. Specifically, pirates might fight over injured pride, insult, gambling, or a woman’s attention. Personal conflict, rum, and the confines of a vessel at sea doubtless fueled many of these deadly challenge fights.

(Numerous books and studies investigate the social origins of the European mania for dueling, and some include analysis of the actual practice of dueling. Among my favorites are V. G. Kiernan, The Duel in European History; François Billacois, The Duel: Its Rise and Fall in Early Modern France; and, probably my most favorite, Pascal Briost et al, Croiser Le Fer: Violence et Culture de l’Epée dans la France Moderne.)

According the Francis Rogers in a journal entry dated 1705 in regard to the Jamaica colonists, “Sword, or sword and pistol, is the common challenge to decide their affronts; except among the ordinary or sea-faring there the fuzee [flintlock musket] or cutlass is the weapon.”

It was not just buccaneers who were inclined to fight duels: the practice was commonplace. Quoting Francis Rogers again on the subject of Jamaican colonists, “They seldom want courage, being too forward in duelling on very slight occasions, standing much on their honour and scorning little base litigious actions.” Likewise the French and French colonists, and the Dutch as well. And Spaniards, including Spanish pirates? Likewise surely, given Iberian honor.

Among the late 17th century buccaneers and boucaniers (cattle and swine hunters who often sailed with buccaneers, some even becoming full-time buccaneers), the fusil boucanier aka “buccaneer gun” — a very long-barrelled, heavy caliber, typically (but not always) club-butted musket used to hunt cattle, swine, and Spaniards — was the primary dueling arm, at least among French buccaneers (the English and Dutch may have used it or another), and not the cutlass or other sword.

According to buccaneer-surgeon-author Alexandre Exquemelin, these musket duelists drew lots to see who would fire first, then stood at a predetermined distance apart. One hundred yards was a likely distance, in that it required reasonable skill to hit a man-sized target at this range. First the winner of the draw fired, then, if still standing, the loser. A surgeon examined any dead body to make sure there had been no back shooting. Such duels could only be fought ashore.

Cutlass duels were likely as well, but unfortunately we lack the descriptions of many duels, and in the case of affrays, especially when liquor was involved, the pistol or musket might be the weapon grabbed first. At sea, Captain Bartholomew Sharp once took a pistol shot at one of his buccaneer crew, Richard Hendricks, barely missing killing him. All involved were drunk. Ashore, Captain John Coxon took a shot at Captain Peter Harris, possibly with a musket. A duel, perhaps, or an angry affray. In any case, the shot fired in anger was due to personal animosities and competition among leaders. Captain Robert Searles, who sacked St. Augustine in 1668 and, drunk and otherwise engaged, permitted the treasure ship Trinidad to escape with much of the city’s treasure during the sack of Panama in 1670, was killed by another buccaneer while cutting logwood at Laguna de Términos, Mexico, although the circumstances are unclear: a duel, an affray–or murder?

No matter the weapon used, duels were usually fought ashore, for two primary reasons: there was more space in which to fight than in the close confines of a vessel, and the time required for a ship to anchor or even for the adversaries simply to be rowed ashore gave time for hot heads to cool. This is not to suggest that duels might never have been fought aboard ship, but if they were they were rare among buccaneers and the evidence for them is largely non-existent but for one source that states that some duels were fought aboard ship among buccaneers, a Dutch practice perhaps.

The source that suggests this is Zeer Aanmerkelijke Reysen Gedaan door Jan Erasmus Reining by Dr. David van der Sterre. Published in 1691, the book is a biography of Captain Jan Erasmus Reyning, one of many colorful buccaneers of the era. Van der Sterre said he met him at Curaçao and wrote a book based on the tales Reyning told. However, the book is of a common style of the era, that of the heavily-embellished biography and it is difficult to tell what is true and what is imagined.

According to the book, duels were common, including between captains and members of the crew due to the aggressive independent nature of buccaneers and their sense of each being primus inter pares or first among equals. One captain reportedly threw two cutlasses onto the deck of his vessel, challenging an impudent crewman. They then fought “like lions” until the crewman fell overboard, at which point the captain followed, hoping to cut him down in the sea.

Van der Sterre also describes a duel, again aboard ship, between the infamous, probably borderline psychotic, Captain Roc Brasiliano, aka Captain Rocky aka Gerrit Gerritsen, and Reyning, the latter in command of a buccaneer vessel sailing in consort with Brasiliano in 1668. Reportedly, Captain Rocky struck Reyning’s close friend Jelles de Lecat, later better-known as Captain Yellows and who was serving as Rocky’s quartermaster, for which Reyning challenged him.

The two fought on deck with “houwers” (hewers, hackers — slang for cutlasses; the term sabel or saber, a general term for cutting sword, is also used), with several wounds received each, Reyning having the upper hand in the end. Van der Sterre writes that Rocky ordered his surgeon not to attend to Reyning’s wounds. In response, Reyning threatened to throw the surgeon’s instruments and medicines overboard; Rocky and the surgeon relented. Later, ashore at the Cayman Islands, Captain Rocky acquired a Spanish rapier and challenged Reyning again, who replied that he had a brace of pistols ready. The two vessels soon parted company and the adversaries did not fight again.

I’ve gone into detailed analysis of this duel in The Golden Age of Piracy. Suffice it here to note that the vessel was small, and that any duel fought in such conditions would force the adversaries to fight close, likely resulting in severe cutting wounds. But the duelists’ wounds, although requiring the ministrations of a surgeon (Rocky had three cuts, Reyning two), were not incapacitating. I suspect the duel, if it occurred, took place ashore or was grossly embellished, or both. Its description is highly detailed, a rarity in accounts of duels of the era. The exceptions are notable: Donald McBane’s personal accounts of his duels for example.

Could the duel have happened as described? Sure. And the fact that each man was wounded multiple times rings true, and one exchange — one man cut in the knee while the other was cut in the head, a classic, if bungled, attack at the knee which the adversary attempts to “slip” and cut at the head — is entirely likely. In fact, the bungling is quite realistic, for sword fights were rarely clean-cut (apologies for the pun!). But light cuts to the head, not to mention all the wounds received here, practically demand longer distance, ashore in other words. In all of my attempts at practical reconstruction of such duels in confined areas, as on a small vessel, both I and my adversary came to close distance, with stout blows (and black bruises) given from our hickory-bladed cutlasses, which, if made with real weapons, would have been severe. Of course, it’s also possible that neither duelist really wanted to seriously hurt the other, much less get hurt, and played it cautiously, hoping simply to draw enough blood to end the fight — which in this case was ended when Rocky took a cut to the forehead and, possibly, could no longer see, a common end to duels with cutting blades.

Further, the duel is corroborated nowhere else, including in Exquemelin’s detailed account of Roc Brasiliano’s life, although Van der Sterre considers this a deliberate slight against his hero. More so, Reyning’s biography is written with a novelist’s eye for detail — with an eye to popular consumption, that is, making it rather suspect. And all other accounts of duels among buccaneers, and even of seafaring men in general of the era, indicate that they were fought ashore. It’s also not unknown for old seafaring adventurers to exaggerate or even invent “sea stories,” taking great pleasure in misleading the gullible.

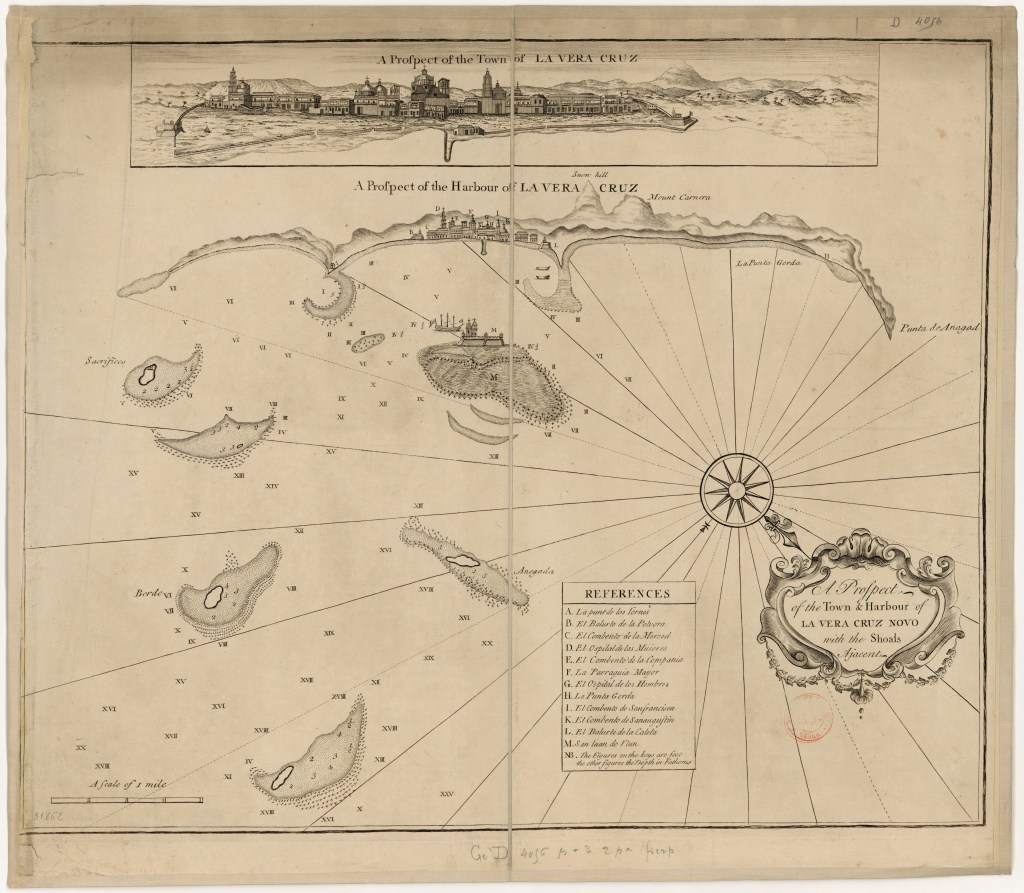

Without doubt the most famous duel among buccaneers, really a quick affray, is that between the famous Dutch buccaneer in French service Laurens de Graff and the dilettante Dutch buccaneer in French service Nicolas Van Horn. The two men despised each other. In particular, de Graff considered Van Horn a pompous fool who had by lack of patience recently lost them the treasure of the Honduras urca. The two captains, along with French gentleman-buccaneer Michel, sieur de Grammont, were co-commanders of the brutal 1683 sack of Veracruz. As the buccaneers loaded their ships with plunder and slaves on Isla Sacrificios, where they had moved from the city for security, de Graff and Van Horn’s contempt for each other came to a head.

Historical sources are uncertain on the real reason or reasons for the duel. There was the urca incident. According to Exquemelin, on the morning of the duel an English buccaneer reported that Van Horn had called de Graff a coward. Van Horn was reportedly angry that de Graff had prevented him from decapitating a dozen prisoners in retaliation for Spanish soldiers firing at French buccaneers who were fetching cornmeal to feed prisoners. Some say there was an argument over what to do next, after the sack of the city: Van Horn wanted to attack the treasure fleet in the offing, but de Graff wanted to depart with what they had, rather than risk losing it. An English governor later wrote that they fought over the division of spoils. And some Spaniards wrote later that the men fought over who could choose how the spoils were divided.

But no matter. Alexandre Exquemelin claims de Graff drew his sword, faced Van Horn, and said, “Voilà! With this I shall avenge the insult you have given me.” If so, Van Horn was damned slow in heeding the warning and drawing his own cutlass and coming on guard.

The fight was a quick one.

According to Fray Avila describing the sack of Veracruz in 1683, “On Thursday afternoon Admiral Lorenzo [Laurens de Graff], seeing how we suffered [from thirst and hunger], told the General [Nicolas Van Horn] that they should cast us ashore as I wanted them to do. The General grew angry and told me he would put us to the sword. At these words the Admiral drew his cutlass with such agility that before the General had put himself on guard Lorenzo had cut him in the arm and ear. They [the pirates] stopped them and I heard the admiral call his soldiers and send him [Van Horn] to his ship which was the almiranta [Van Horn’s St. Nicolas, soon to become de Grammont’s Hardi], and from this day we saw him no more.”

Call de Graff’s cutlass stroke Dutch buccaneer iado if you like. We can speculate on how de Graff made his cut or cuts: a single cut upward from the scabbard striking wrist and forehead; a single blow from high to low after drawing (“lugging out” was the term in English for drawing a sword); or two cuts, perhaps the first from low to high cutting the wrist, and the second from high to low cutting the forehead. Or any of several other possibilities. Van Horn died some days afterward, possibly of gangrene, or possibly of a pestilence that swept through his crew. His death was formally laid at the feet of de Graff, who, when he was considered for a commission as a French officer a few years later, had to petition for and receive a royal pardon for killing Van Horn.

Not quite Flynn versus Rathbone aka Peter Blood versus Levasseur, but nonetheless a duel between pirate captains on a sandy shore in the 1680s — about as close historically as we can get to that most famous of film duels!

Although cutlasses were probably the norm for duels among buccaneers when muskets were not used, and likely enough among buccaneer captains, smallswords may have been used on occasion although we have no record of this. A small but fair number of buccaneers, French in particular, were gentlemen who would have been trained in the use of the smallsword, would have preferred it for formal combat, and may have carried it even in battle.

The sieur de Grammont noted above had fought at least one duel long before becoming a buccaneer: he ran his sister’s suitor thrice through. Also among these French gentlemen-buccaneers were famous buccaneer-author Raveneau de Lussan; the sieur de Chauvelin who served under de Grammont aboard one of his consorts, a half-galley and who was killed in Florida in the aftermath of an aborted attempt on St. Augustine; and the sieur d’Hulot, a veteran of two campaigns against Algiers and the Algerine corsairs, and who would later command the regular French forces on Saint-Domingue. Alas, we have no record of any duels among these smallsword-wielding gentlemen, much less of any smallsword duels on the beach.

An interesting adoption of an army dueling practice was reportedly undertaken by Red Sea pirates circa 1693-94. According the deposition of pirate Samuel Perkins in 1698, fourteen pirates, variously from the crews of captains Thomas Tew, Josiah Raynor, William Mason, and Edward Coats, divided into two factions of seven each on St. Mary’s island some five years prior, “to fight for what they had (thinking they had not made a voyage sufficient for so many) and that one of the said Sevens were all killed, and five of the other, so that the two which survived enjoyed the whole Booty.”

What weapons were used is unknown, but cutlasses are likely. And the amount of booty? If this took place in the year 1693, Tew’s crew shared 1,200 pounds (the equivalent of 6,000 pieces-of-eight) per man, an extraordinary sum, making it unlikely any crew would fight to increase this — unless they had lost their shares gaming. Such losses might make desperate men even more desperate, willing enough to fight in a group duel in which most were likely to be killed. A year prior, the crew of Edward Coats shared 500 pounds per man, still a large booty and three or more times what would be considered a profitable voyage among the Caribbean buccaneers.

It was not uncommon for army regiments, particularly during winter quarters or in garrison, to settle conflicts this way, each choosing their best swordsmen to fight those of the other. Sometimes all fought at the same time, sometimes only one from each side would fight, the victor staying up to fight the next until defeated, then another would take his place.

Famous Scottish soldier, swordsman, duelist, fencing master, and prize fighter Donald McBane describes one such compound duel, its occasion being McBane’s theft of fourteen prostitutes from a Dutch regiment — the Scotsman had a profitable side gig of gambling and prostitution. The “next Day came Twenty-four Swords Men and Demanded the Lasses again, or else give them Satisfaction, we made up Twenty-four Men and Drank together; then we Fought two and two, there was Eleven of the Dutch Killed and Seven of our Men, our Bargain was, that if they beat us, we were to give them the Lasses and Pay them a Tribute, and on the contrary, they were to Pay us Tribute: We fought a Second Time, I being of the Royal it fell to me to Fight first, the first Time I was soon done, but the Second Time before I put I my Sword, I Fought Eight of them so it ended, and they promised to Pay their Tribute, we buried our Dead and parted…” But the Dutch didn’t pay, and shot four of the six men sent for the tribute two or three days afterward.

Early eighteenth-century pirates of the Black Flag reportedly fought duels with pistols ashore, to be followed by cutlasses if necessary, at least according to pirate chronicler and liar-when-convenient Charles Johnson (a pseudonym). The articles of Bartholomew Roberts and his crew reportedly provided that “The Quarter-Master of the Ship, when the Parties will not come to any Reconciliation, accompanies them on Shore with what Assistance he thinks proper, and turns the Disputants Back to Back, at so many Paces Distance: At the Word of Command, they turn and fire immediately, (or else the Piece is knocked out of their Hands:) If both miss they come to their Cutlashes, and then he is declared Victor who draws the first Blood.” Note that this quotation is from a secondary source, albeit a period one, not an primary source; no original examples of pirate articles from the 1714 – 1726 Black Flag era exist.

There were other methods of dueling with pistols during this era, and it is possible that pirates may have used some of them as well. For example, Donald McBane describes a form of pistol duel in which a cloak is held up in each duelist’s left hand so that neither man can see the other, then on cue pistols are fired through the cloak.

One wonders at the description of pistol dueling — generally considered in the popular historical fiction mind to have been a deadly form of honor combat — engaged in first among the Black Sail pirates of Roberts’s crew, to be followed by cutlasses merely to first blood. This is in fact unsurprising: 19th century sources note that pistol duels were far less dangerous than sword duels, and this in an era in which pistols were more accurate than in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. One commentator wrote that only one in six pistol duelists were wounded, and only one in fourteen killed. In sword duels, one or both duelists were nearly always wounded or killed, although another commentator noted that pistol wounds were usually far more dangerous than sword wounds. Pistol dueling grew in popularity as a means of showing one’s “bottom” aka courage, yet it was less dangerous by far than sword duels (unless one got shot), at least until the development of the epee de combat and light Italian dueling sabre in the late 19th century, much of whose swordplay and design were intended to minimize the risk of fatal wounds in an era in which dueling remained popular yet the law had begun to severely punish dueling’s most severe results.

Notably, in spite of their romance and implied associated courage, all forms of dueling were less dangerous than the battlefield of sea or shore.

Charles Johnson describes an early 18th century challenge and its aftermath among pirates. Assuming he is telling the truth, the bosun of Captain Evans, a pirate, challenged his captain to a duel with sword and pistol “on the next shore they came to.” Unsurprisingly — challenges are easy, following up on them much more difficult — the bosun declined to fight, for which Captain Evans caned him. The bosun in turn shot him through the head and leaped overboard to swim ashore but was taken up by the pirates. For this murder the pirate crew resolved to torture the bosun, but the gunner, inflamed with passion, shot him through the body instead. The bosun, not killed, begged a week for repentance. He “should repent and be damned to him,” said another pirate, who then shot the bosun dead.

Thus ends our brief foray into the reality of piratical duels on the beach. As I close this latest blog post, here’s something to note: duels in film and fiction must be exaggerated in order to keep the viewer or reader’s attention. Not so with reality: even a simple, short duel is exciting for the simple reason that real bloodshed is likely.

N. B. The captions at the foot of the first image above read “Outside parry with the forte” & “The thrust made against those who raise their sword when parrying.” The latter thrust would be typically made if the adversary delays the riposte, or as a “high-low” feint attack. Many period masters would disagree with the extension of the un-armed hand, preferring to keep it by the head, ready to parry or oppose.

Copyright Benerson Little 2024. First published August 20, 2024. Last updated September 23, 2025.