Home » Posts tagged 'counter-attacks'

Tag Archives: counter-attacks

The Night Thrust; or, More Politely, the Passata Soto

“This subterfuge is termed a Night-Thrust; being a short method of deciding a skirmish in the dark.”

–Andrew Lonergan, The Fencer’s Guide, 1777.

But Edward was no longer there, or at least not where Lynch expected. Completely covered by the inky darkness, Edward had lunged backward, his left hand dropping to the ground, his body bending inward, his blade shooting forward at Lynch’s belly: the Italians called this passata soto, but some of Edward’s English contemporaries called it the “night thrust” for its utility in the darkness.

Benerson Little, Fortune’s Whelp, 2015

The Classic Passata Soto or “Night Thrust”

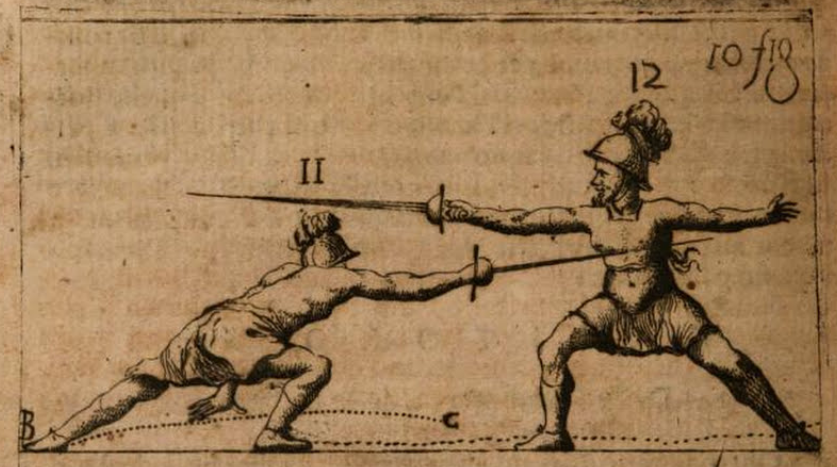

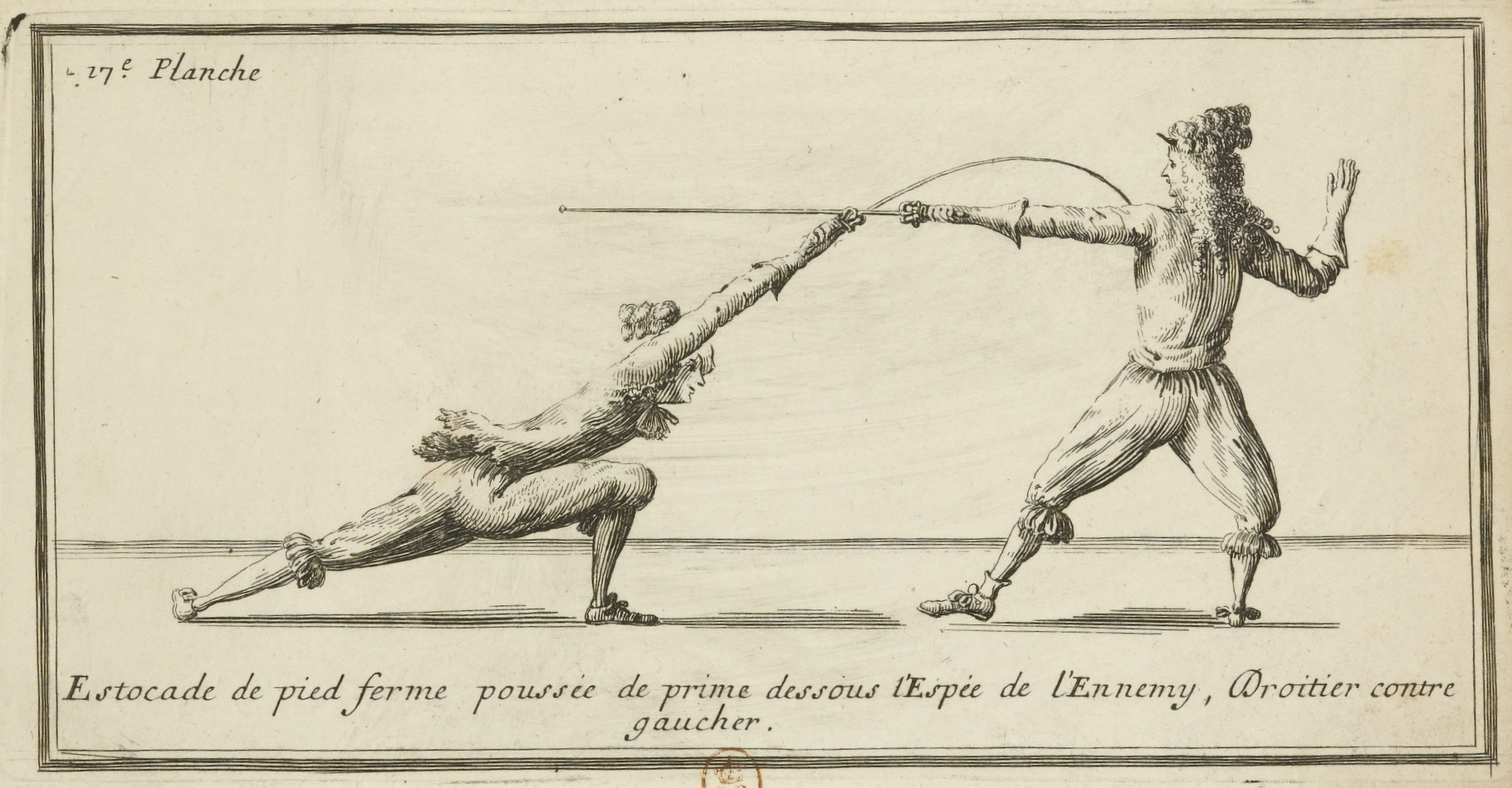

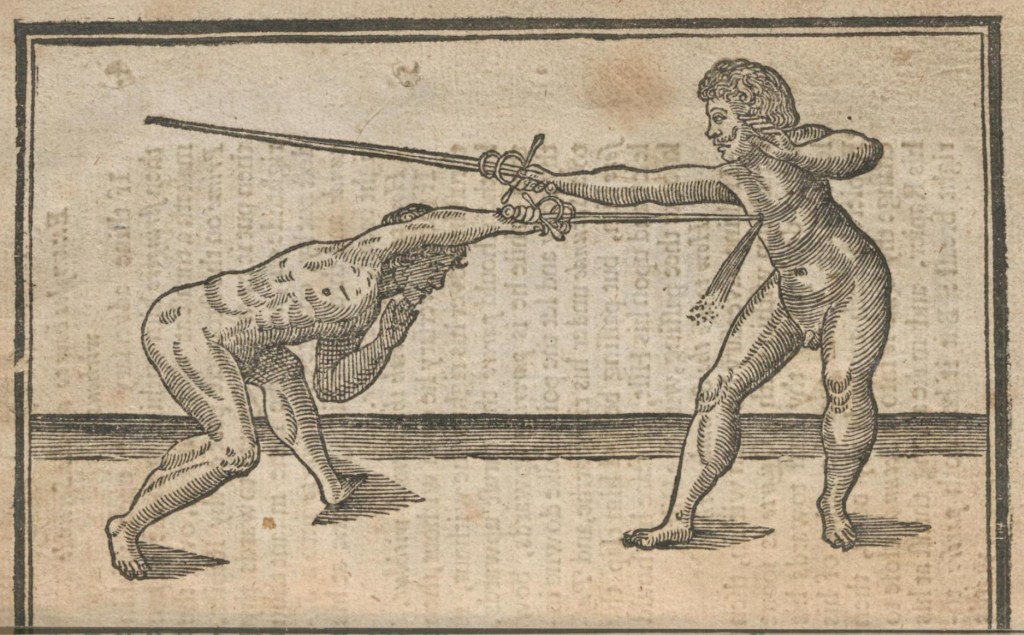

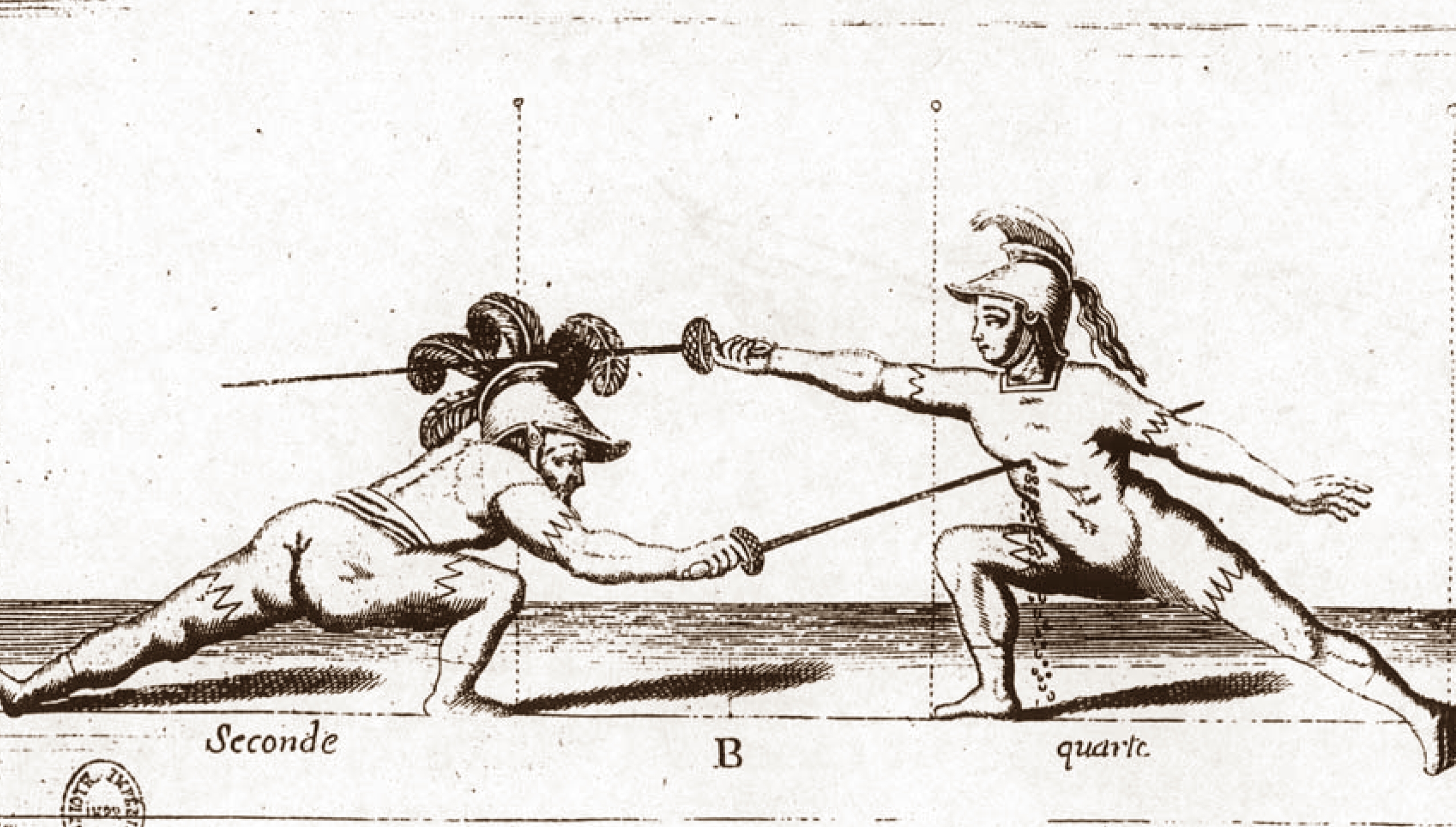

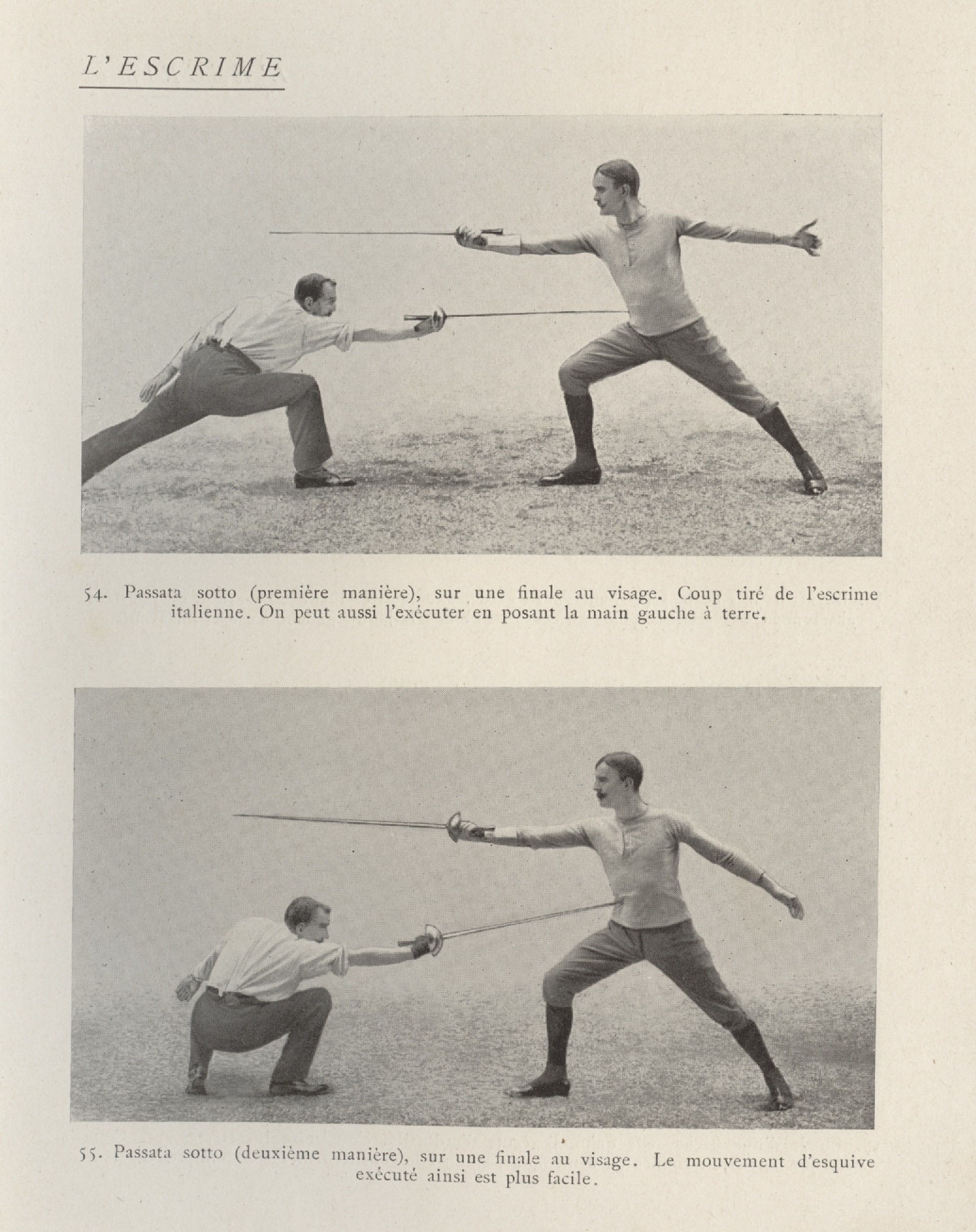

A staple of many Western fencing texts since the Renaissance, the passata soto, or passata sotto, also known variously as the sbasso, sottobotta, and cartoccio on occasion, the various dessous of the French masters of the smallsword and the passata di sotto of the modern, is usually defined as a counter-attack made by lowering the body while simultaneously thrusting, extending the rear foot in a reverse lunge, and placing the unarmed hand on the ground for support. Occasionally the technique is recommended as an attack with a true lunge, rather than a reverse. Andrew Lonergan provides an eighteenth century definition and exercise of the passata soto under the name of night thrust:

“On Guard in Quarte; and disengage a Quarte-over-the-arm [modern sixte]. I now batter [beat] with a Tierce; and begin to advance my left foot to form my Pass upon you in Tierce. Now when you see my left foot move, slip your left foot back, so as to pitch yourself on that knee; stoop your head so that your arm now turned into a Segonde may cover it, hold your left hand extended toward the ground, that it may sustain you, in case you should totter; thus my point will pass over your head, and I shall fall upon yours.”

And his reasoning why such “athletic” techniques should not be abandoned:

“Though these methods of Disarming, and Passing, Volting, and that of the Night Thrust, seem to be almost abolished by the refiners of these arts; I cannot conceive why a man, who is naturally strong and active, should not avail himself of such advantages, especially when improved by our athletic exercises, so engaging to an English subject, and forbidding to all others.”

In the old Italian schools, the body was usually bent at the waist. In some of the old French, the body was lowered by a very low reverse lunge. The adversary may be hit either with the extending arm or by impaling upon it, or both.

In terms of the modern French school, the “passata di sotto” is classified as an esquive, specifically une passe dessous with the back leg extended or both legs deeply bent.

With real weapons, the adversary is ideally impaled, usually in the belly which is, were the swords real, a good place to hit because there are no ribs and cartilage to potentially prevent the point from entering or otherwise diminish its penetration. There is also some anecdotal evidence to suggest that in some cases belly wounds may be more quickly incapacitating.

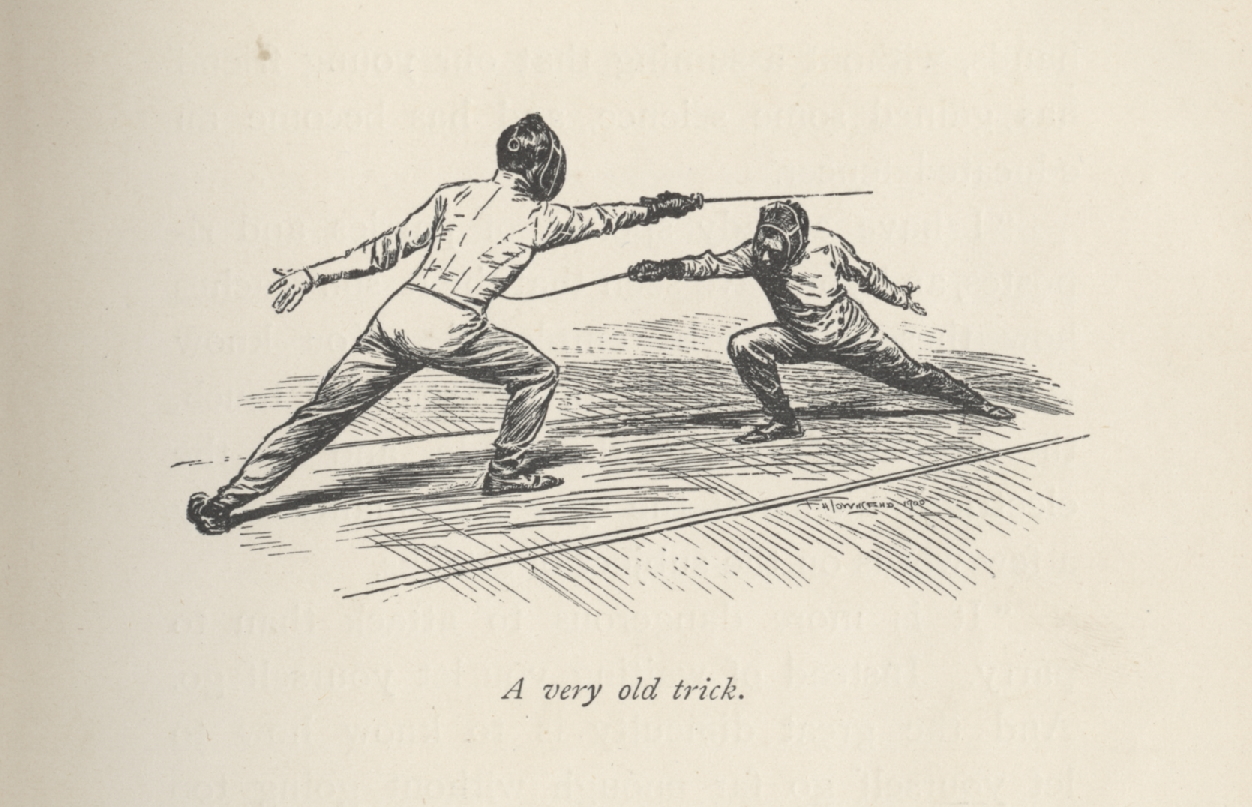

A very long low lunge which made going forward might slip under the adversary’s guard, as in Rafael Sabatini’s novel The Black Swan (1932), and which made in reverse might serve aid a counter-attack by lowering of the body. (An analysis of the duel in the novel may be found here: The Duel on the Beach, Part II: The Black Swan.)

Long low lunges like this are often identified with, or confused with, the passata soto. Note, however, that fencing language is highly malleable and definitions vary: one master’s passata soto might include only the classic reverse lunge with a bend at the waist, while another’s may include any lowering of the body in attack or counter-attack. Most masters, however, consider it to be a counter-attack with esquive, the body lowering in place or with a reverse lunge, and not a long low lunge forward.

The passata soto is not without significant drawbacks, which is probably why Lonergan recommended its use at night and nowhere else. Foremost, it must be well-timed. Too late, and the fencer attempting it may get hit in the face, neck, or upper torso. Too soon, and the fencer attempting it throws away the advantage of the surprise mandatory to its success. Used too often, and the adversary may learn how to trigger it with a feint, and then take advantage of the poor position the classical passata soto leaves the fencer in.

And it is this poor position that is the major drawback of the passata soto, in particular with real weapons. With the unarmed hand on the ground, the torso bent sideways, and the rear leg extended well behind, the fencer is in a bad position for defense after a failed attack or, even if the swords were real, after impaling the adversary. Few wounds are immediately incapacitating, including ultimately fatal wounds: many duelists and battlefield swordsmen were wounded or killed after giving an adversary a fatal wound. Even with a mortal wound to the heart, an adversary may live as long as ten seconds. Even assuming an average of four, that’s plenty of time to even things up.

In the case of dry (non-electric) weapons, the judges and director (referee) will determine whether a hit was made, whether it was in time, and whether a hit on the fencer who ducked is valid via rules regarding replacing of target. In the case of electrical weapons, the machine will make the determination in epee, and the machine and director in foil and saber.

For the fencer armed with a rapier on poniard, placing the poniard-armed hand on the ground is giving up half of one’s offense and defense, to be replaced by almost blind trust.

From the position of the passata soto, a prime or lifted sixte/septime beat or bind, or a St. George parry or opposition (modern saber quinte) accompanied by the use of the unarmed hand to help ward off the adversary’s blade, plus an urgent recovery forward or backward, all performed near-simultaneously, is the only viable option if the passata soto has failed to hit or otherwise halt the adversary.

Such recovery, however, is invariably slow, and a loss of balance may ensue if the unarmed hand is removed from the ground too soon to assist in parrying or opposing, for example. Further, the long low position leaves the fencer vulnerable if the arrest fails, whether by missing the adversary or failing to immediately incapacitate him. In particular, the head, neck, and subclavian area are exposed. Fatal thrusting wounds can be given in any of the three areas. It’s likely that execution at night might alleviate some of these weaknesses in the technique, but it would need to be a dark night with little ambient light.

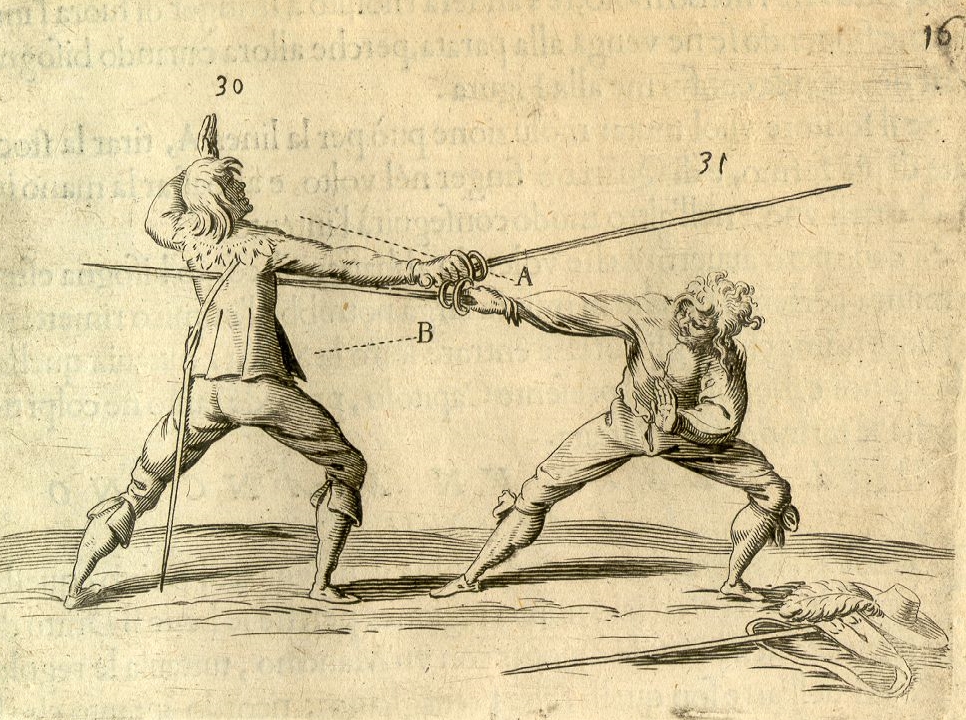

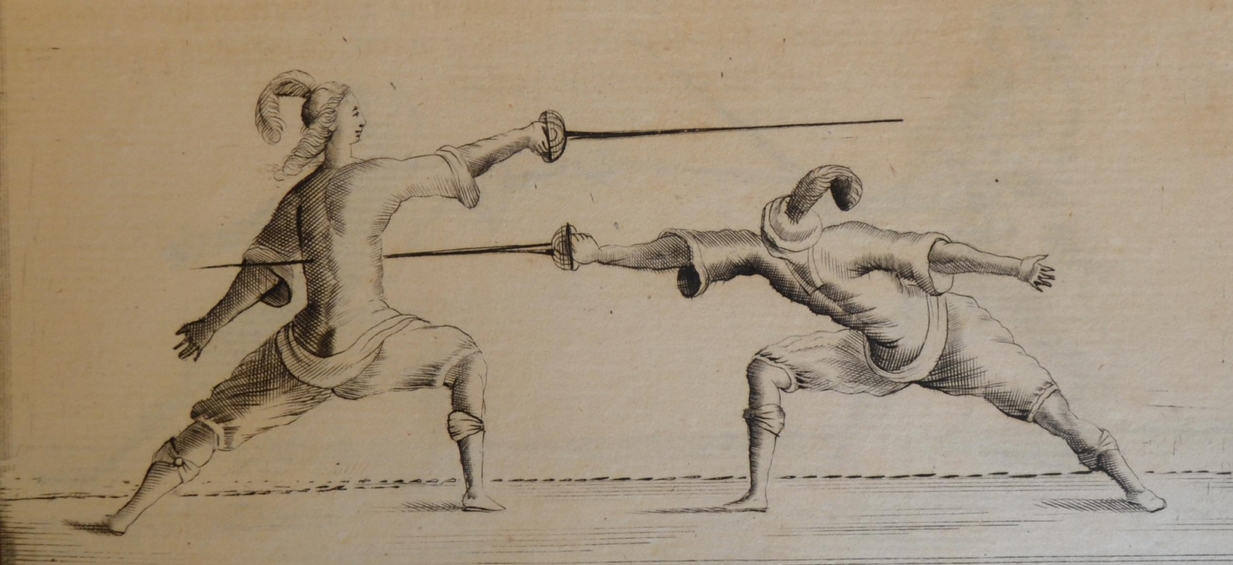

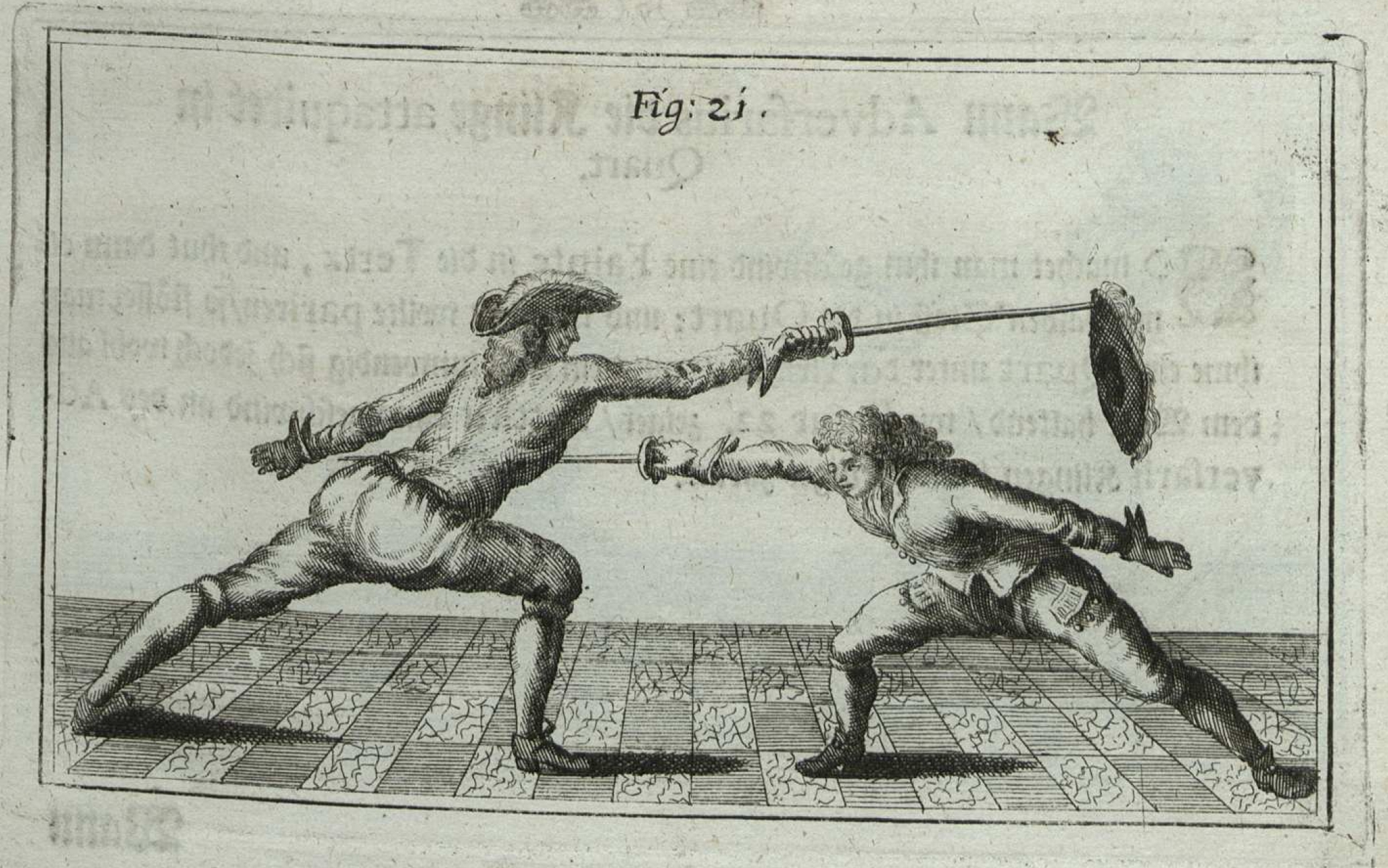

Historical Techniques Similar to Passata Soto

There are better methods, past and present. In particular, these methods, while not reducing the target quite as much, leave the fencer in a much better position should the counter-attack fail, or, with real weapons, should the adversary be hit but not be immediately incapacitated. Some masters, Sir William Hope for example, believed also that a lowered position better-protected the torso.

In general they consist of a lowering of the body to a lesser degree, often with a parry or beat first, or with a thrust in opposition. Below are a series of images depicting this in various forms over time.

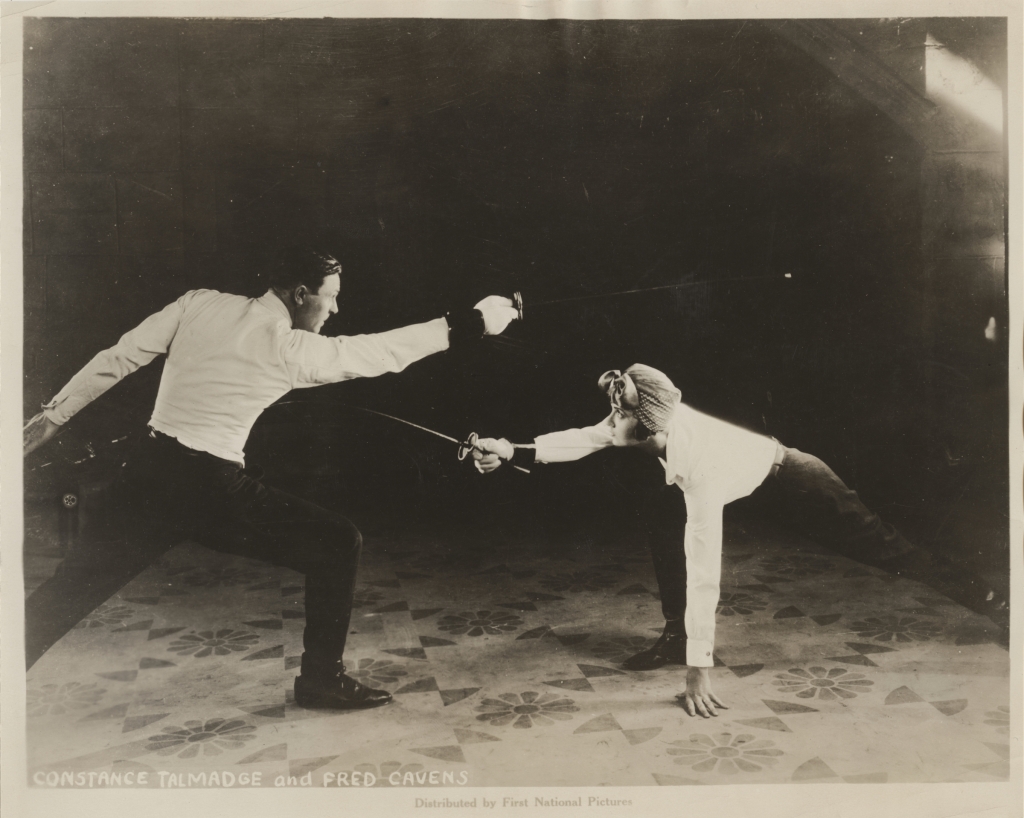

The Passata Soto in Film

The passata soto is seldom shown in film, unfortunately, but here are four associated examples:

The Passato Soto in Modern Fencing

In modern competitive fencing, the technique is still occasionally seen in its classical form, in particular against a flèche, but more often is seen in the modified form of “squatting.” This is not a new technique! It was noted by Jean Joseph-Renaud more than a century ago. He correctly–as expected–notes that the latter form is easier.

In the spring of 1978 I saw it well-used by a University of Southern California epeeist–I made up the weakest third of the USC epee team, having fenced for less than a year–at a large collegiate meet at the University of California San Diego. The score was la belle (4-4), with no time limit for the final touch as I recall. (It was a nice rule that, of no time limit for the last touch! It’s long since been sadly abolished in the name of expediency…)

Suddenly both fencers stopped and pulled off their masks, but for no reason other than that they had heard the bell on the adjacent strip and, their adrenalin up for the la belle touch, mistook it for theirs. The young director… Hold on for a moment. Today the director, from directeur de combat, the person who “directs” a duel, is called a “referee,” solely because the foolish powers that be thought it would make fencing more spectator friendly… Seriously.

But back to our anecdote. The young college-age director, rather than enforcing the halt and putting the fencers back on guard, said “I didn’t call halt!”

You know what surely happened next. Without putting masks back on, immediately the opposing team’s fencer flèched while ours dropped into a beautiful passata soto. We got the touch and the bout. Neither fencer, thankfully, was hit in the unprotected face. Or at least that’s how I recall it happened.

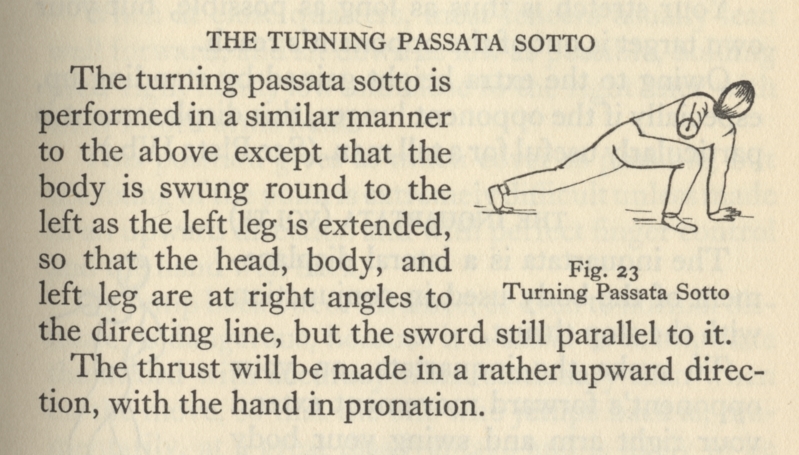

In modern usage, although infrequently seen, is a form known as the “turning” passata soto. The description is best left to R. A. Lidstone:

In competitive use, the modern form most often takes the form of ducking or squatting, shown below. Ducking has been used for at least seventy-five years in modern fencing.

Copyright Benerson Little 2017-2023. Last updated October 24, 2023.