Home » Posts tagged 'flibustiers'

Tag Archives: flibustiers

The Duel on the Beach, Part V: In Reality

If you’ve read any or all of parts I though IV of this series (In Fiction, In Film, in Rafael Sabatini’s novel The Black Swan, and of the duel between Flynn and Rathbone in Captain Blood, you might be wondering if novelists and Hollywood have depicted buccaneer and pirate duels, a common trope of the genre, accurately. Like much that is popular buccaneer and pirate image, the answer is “yes and no,” or more precisely, “sort of sometimes, but mostly no.” If anything, the duels imagined on page and screen have caught some of the spirit of historical buccaneer and pirate duels, rather than actual practice.

One thing we’re sure of is that the real duels probably did not look like those engaged in by the swordsmen in the plate above!

N. B. Besides the links above, more information about dueling, swordplay, and swords among sea rovers and mariners of the era in general can be found in Buccaneer Cutlasses: What We Know; in chapter 17 of The Buccaneer’s Realm; and in chapter 8 of The Golden Age of Piracy, which has more detail and analysis than is found in this post.

We know that buccaneers and pirates fought duels occasionally, although detailed accounts of individual duels, with an exception or two, do not exist. Further, we know even less about the tactics and techniques of individual duels. In fact, only rarely do we even know what weapons were used in specific duels. Often the description is as spare as, “Here it was that our quartermaster, James Chappel, and myself fought a duel together on shore,” as buccaneer-surgeon Basil Ringrose wrote.

And why were duels fought among buccaneers and pirates? For the same reason they’ve always been fought: usually out of some misguided form of honor, although doubtless there were occasionally good reasons to fight. The gamut of human emotion easily gave rise to duels: jealousy, envy, avarice, lust, deep-seated insecurity, narcissism, pride and its exaggeration hubris, competition, and more. Specifically, pirates might fight over injured pride, insult, gambling, or a woman’s attention. Personal conflict, rum, and the confines of a vessel at sea doubtless fueled many of these deadly challenge fights.

(Numerous books and studies investigate the social origins of the European mania for dueling, and some include analysis of the actual practice of dueling. Among my favorites are V. G. Kiernan, The Duel in European History; François Billacois, The Duel: Its Rise and Fall in Early Modern France; and, probably my most favorite, Pascal Briost et al, Croiser Le Fer: Violence et Culture de l’Epée dans la France Moderne.)

According the Francis Rogers in a journal entry dated 1705 in regard to the Jamaica colonists, “Sword, or sword and pistol, is the common challenge to decide their affronts; except among the ordinary or sea-faring there the fuzee [flintlock musket] or cutlass is the weapon.”

It was not just buccaneers who were inclined to fight duels: the practice was commonplace. Quoting Francis Rogers again on the subject of Jamaican colonists, “They seldom want courage, being too forward in duelling on very slight occasions, standing much on their honour and scorning little base litigious actions.” Likewise the French and French colonists, and the Dutch as well. And Spaniards, including Spanish pirates? Likewise surely, given Iberian honor.

Among the late 17th century buccaneers and boucaniers (cattle and swine hunters who often sailed with buccaneers, some even becoming full-time buccaneers), the fusil boucanier aka “buccaneer gun” — a very long-barrelled, heavy caliber, typically (but not always) club-butted musket used to hunt cattle, swine, and Spaniards — was the primary dueling arm, at least among French buccaneers (the English and Dutch may have used it or another), and not the cutlass or other sword.

According to buccaneer-surgeon-author Alexandre Exquemelin, these musket duelists drew lots to see who would fire first, then stood at a predetermined distance apart. One hundred yards was a likely distance, in that it required reasonable skill to hit a man-sized target at this range. First the winner of the draw fired, then, if still standing, the loser. A surgeon examined any dead body to make sure there had been no back shooting. Such duels could only be fought ashore.

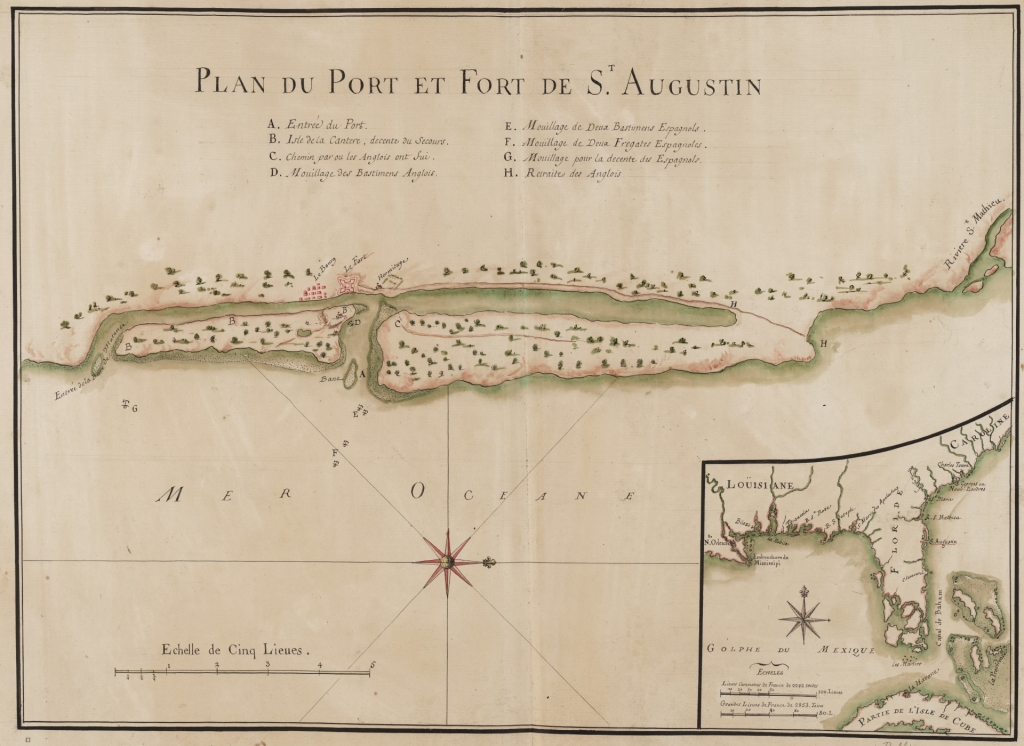

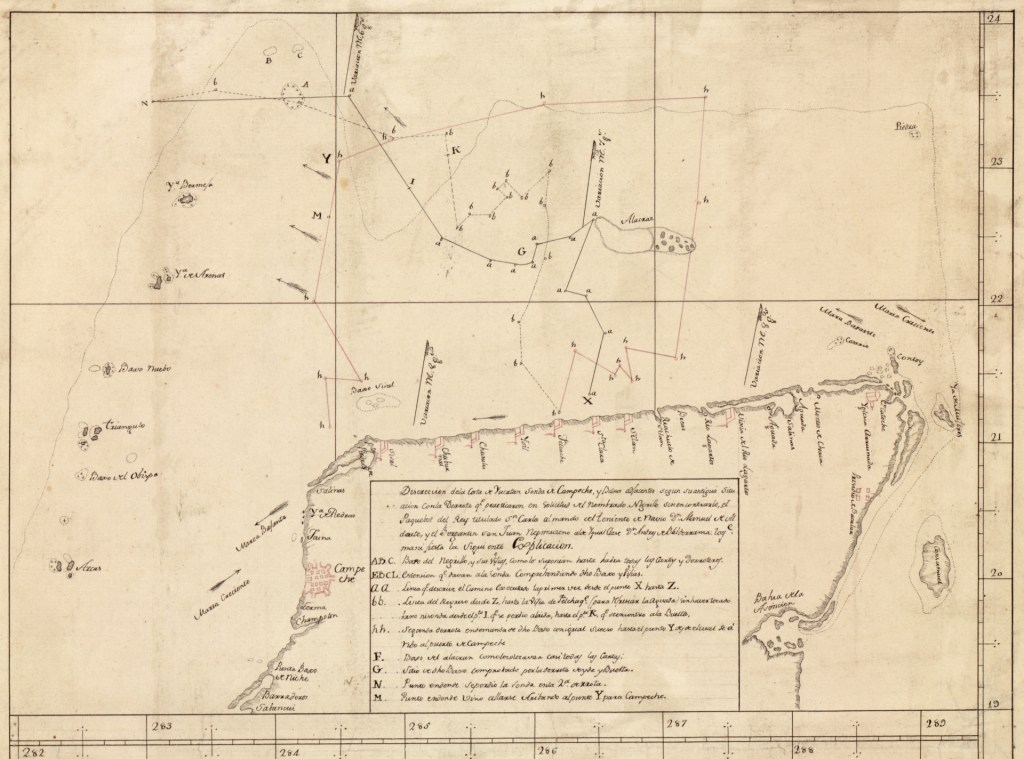

Cutlass duels were likely as well, but unfortunately we lack the descriptions of many duels, and in the case of affrays, especially when liquor was involved, the pistol or musket might be the weapon grabbed first. At sea, Captain Bartholomew Sharp once took a pistol shot at one of his buccaneer crew, Richard Hendricks, barely missing killing him. All involved were drunk. Ashore, Captain John Coxon took a shot at Captain Peter Harris, possibly with a musket. A duel, perhaps, or an angry affray. In any case, the shot fired in anger was due to personal animosities and competition among leaders. Captain Robert Searles, who sacked St. Augustine in 1668 and, drunk and otherwise engaged, permitted the treasure ship Trinidad to escape with much of the city’s treasure during the sack of Panama in 1670, was killed by another buccaneer while cutting logwood at Laguna de Términos, Mexico, although the circumstances are unclear: a duel, an affray–or murder?

No matter the weapon used, duels were usually fought ashore, for two primary reasons: there was more space in which to fight than in the close confines of a vessel, and the time required for a ship to anchor or even for the adversaries simply to be rowed ashore gave time for hot heads to cool. This is not to suggest that duels might never have been fought aboard ship, but if they were they were rare among buccaneers and the evidence for them is largely non-existent but for one source that states that some duels were fought aboard ship among buccaneers, a Dutch practice perhaps.

The source that suggests this is Zeer Aanmerkelijke Reysen Gedaan door Jan Erasmus Reining by Dr. David van der Sterre. Published in 1691, the book is a biography of Captain Jan Erasmus Reyning, one of many colorful buccaneers of the era. Van der Sterre said he met him at Curaçao and wrote a book based on the tales Reyning told. However, the book is of a common style of the era, that of the heavily-embellished biography and it is difficult to tell what is true and what is imagined.

According to the book, duels were common, including between captains and members of the crew due to the aggressive independent nature of buccaneers and their sense of each being primus inter pares or first among equals. One captain reportedly threw two cutlasses onto the deck of his vessel, challenging an impudent crewman. They then fought “like lions” until the crewman fell overboard, at which point the captain followed, hoping to cut him down in the sea.

Van der Sterre also describes a duel, again aboard ship, between the infamous, probably borderline psychotic, Captain Roc Brasiliano, aka Captain Rocky aka Gerrit Gerritsen, and Reyning, the latter in command of a buccaneer vessel sailing in consort with Brasiliano in 1668. Reportedly, Captain Rocky struck Reyning’s close friend Jelles de Lecat, later better-known as Captain Yellows and who was serving as Rocky’s quartermaster, for which Reyning challenged him.

The two fought on deck with “houwers” (hewers, hackers — slang for cutlasses; the term sabel or saber, a general term for cutting sword, is also used), with several wounds received each, Reyning having the upper hand in the end. Van der Sterre writes that Rocky ordered his surgeon not to attend to Reyning’s wounds. In response, Reyning threatened to throw the surgeon’s instruments and medicines overboard; Rocky and the surgeon relented. Later, ashore at the Cayman Islands, Captain Rocky acquired a Spanish rapier and challenged Reyning again, who replied that he had a brace of pistols ready. The two vessels soon parted company and the adversaries did not fight again.

I’ve gone into detailed analysis of this duel in The Golden Age of Piracy. Suffice it here to note that the vessel was small, and that any duel fought in such conditions would force the adversaries to fight close, likely resulting in severe cutting wounds. But the duelists’ wounds, although requiring the ministrations of a surgeon (Rocky had three cuts, Reyning two), were not incapacitating. I suspect the duel, if it occurred, took place ashore or was grossly embellished, or both. Its description is highly detailed, a rarity in accounts of duels of the era. The exceptions are notable: Donald McBane’s personal accounts of his duels for example.

Could the duel have happened as described? Sure. And the fact that each man was wounded multiple times rings true, and one exchange — one man cut in the knee while the other was cut in the head, a classic, if bungled, attack at the knee which the adversary attempts to “slip” and cut at the head — is entirely likely. In fact, the bungling is quite realistic, for sword fights were rarely clean-cut (apologies for the pun!). But light cuts to the head, not to mention all the wounds received here, practically demand longer distance, ashore in other words. In all of my attempts at practical reconstruction of such duels in confined areas, as on a small vessel, both I and my adversary came to close distance, with stout blows (and black bruises) given from our hickory-bladed cutlasses, which, if made with real weapons, would have been severe. Of course, it’s also possible that neither duelist really wanted to seriously hurt the other, much less get hurt, and played it cautiously, hoping simply to draw enough blood to end the fight — which in this case was ended when Rocky took a cut to the forehead and, possibly, could no longer see, a common end to duels with cutting blades.

Further, the duel is corroborated nowhere else, including in Exquemelin’s detailed account of Roc Brasiliano’s life, although Van der Sterre considers this a deliberate slight against his hero. More so, Reyning’s biography is written with a novelist’s eye for detail — with an eye to popular consumption, that is, making it rather suspect. And all other accounts of duels among buccaneers, and even of seafaring men in general of the era, indicate that they were fought ashore. It’s also not unknown for old seafaring adventurers to exaggerate or even invent “sea stories,” taking great pleasure in misleading the gullible.

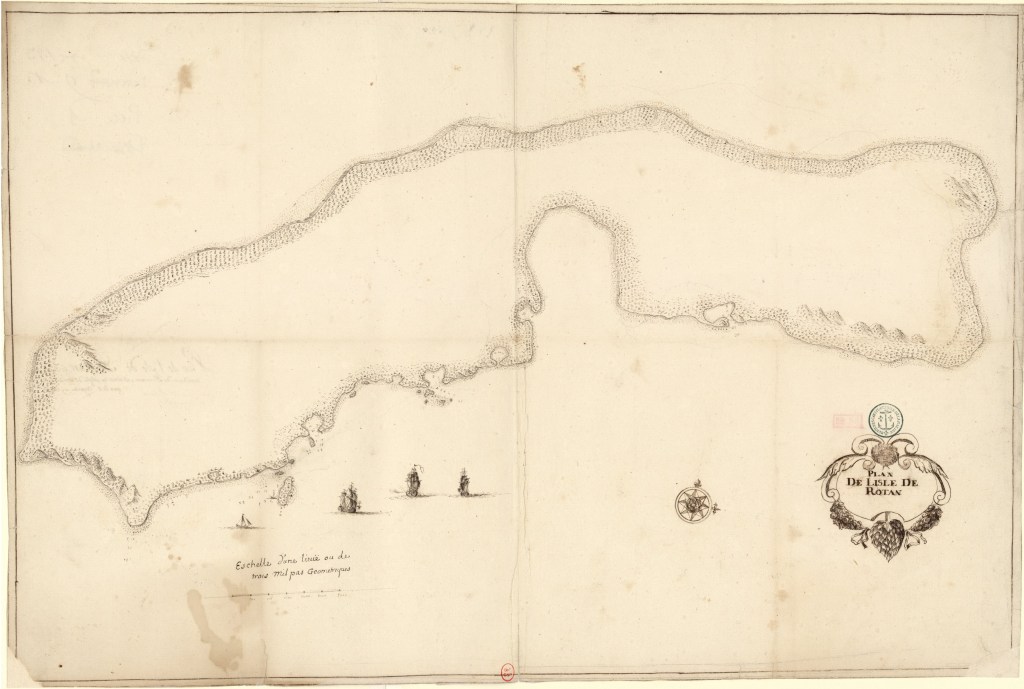

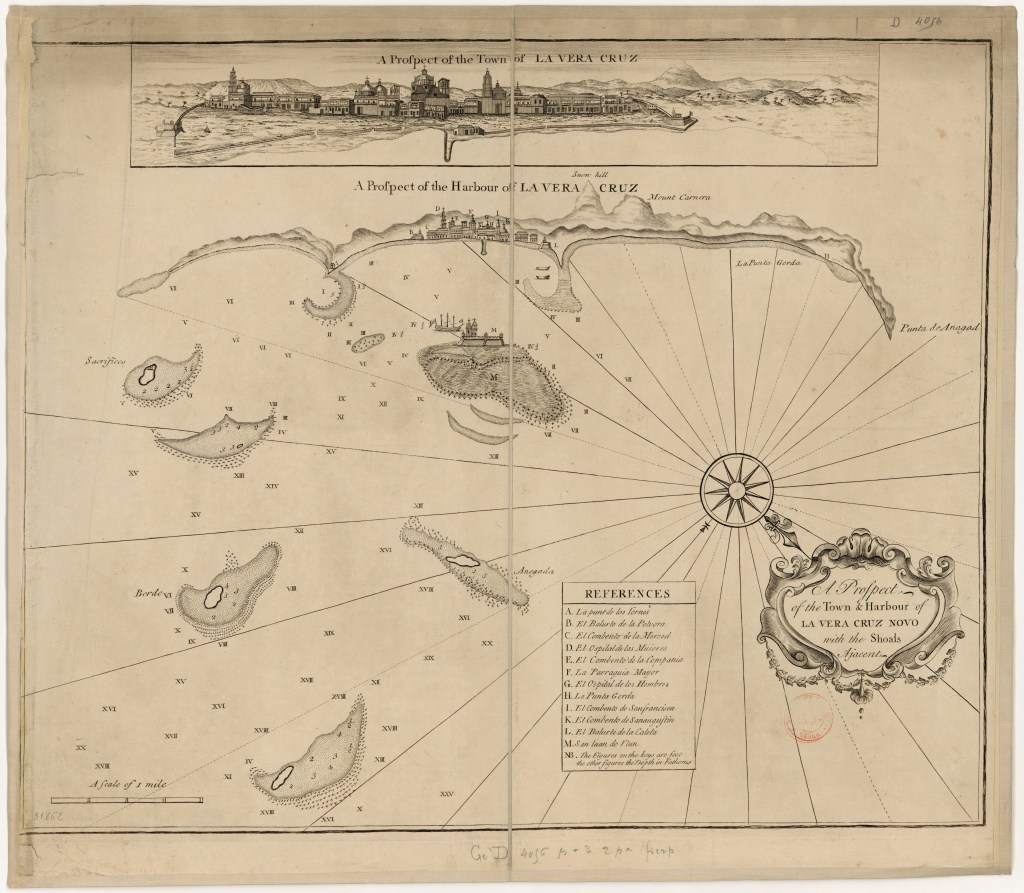

Without doubt the most famous duel among buccaneers, really a quick affray, is that between the famous Dutch buccaneer in French service Laurens de Graff and the dilettante Dutch buccaneer in French service Nicolas Van Horn. The two men despised each other. In particular, de Graff considered Van Horn a pompous fool who had by lack of patience recently lost them the treasure of the Honduras urca. The two captains, along with French gentleman-buccaneer Michel, sieur de Grammont, were co-commanders of the brutal 1683 sack of Veracruz. As the buccaneers loaded their ships with plunder and slaves on Isla Sacrificios, where they had moved from the city for security, de Graff and Van Horn’s contempt for each other came to a head.

Historical sources are uncertain on the real reason or reasons for the duel. There was the urca incident. According to Exquemelin, on the morning of the duel an English buccaneer reported that Van Horn had called de Graff a coward. Van Horn was reportedly angry that de Graff had prevented him from decapitating a dozen prisoners in retaliation for Spanish soldiers firing at French buccaneers who were fetching cornmeal to feed prisoners. Some say there was an argument over what to do next, after the sack of the city: Van Horn wanted to attack the treasure fleet in the offing, but de Graff wanted to depart with what they had, rather than risk losing it. An English governor later wrote that they fought over the division of spoils. And some Spaniards wrote later that the men fought over who could choose how the spoils were divided.

But no matter. Alexandre Exquemelin claims de Graff drew his sword, faced Van Horn, and said, “Voilà! With this I shall avenge the insult you have given me.” If so, Van Horn was damned slow in heeding the warning and drawing his own cutlass and coming on guard.

The fight was a quick one.

According to Fray Avila describing the sack of Veracruz in 1683, “On Thursday afternoon Admiral Lorenzo [Laurens de Graff], seeing how we suffered [from thirst and hunger], told the General [Nicolas Van Horn] that they should cast us ashore as I wanted them to do. The General grew angry and told me he would put us to the sword. At these words the Admiral drew his cutlass with such agility that before the General had put himself on guard Lorenzo had cut him in the arm and ear. They [the pirates] stopped them and I heard the admiral call his soldiers and send him [Van Horn] to his ship which was the almiranta [Van Horn’s St. Nicolas, soon to become de Grammont’s Hardi], and from this day we saw him no more.”

Call de Graff’s cutlass stroke Dutch buccaneer iado if you like. We can speculate on how de Graff made his cut or cuts: a single cut upward from the scabbard striking wrist and forehead; a single blow from high to low after drawing (“lugging out” was the term in English for drawing a sword); or two cuts, perhaps the first from low to high cutting the wrist, and the second from high to low cutting the forehead. Or any of several other possibilities. Van Horn died some days afterward, possibly of gangrene, or possibly of a pestilence that swept through his crew. His death was formally laid at the feet of de Graff, who, when he was considered for a commission as a French officer a few years later, had to petition for and receive a royal pardon for killing Van Horn.

Not quite Flynn versus Rathbone aka Peter Blood versus Levasseur, but nonetheless a duel between pirate captains on a sandy shore in the 1680s — about as close historically as we can get to that most famous of film duels!

Although cutlasses were probably the norm for duels among buccaneers when muskets were not used, and likely enough among buccaneer captains, smallswords may have been used on occasion although we have no record of this. A small but fair number of buccaneers, French in particular, were gentlemen who would have been trained in the use of the smallsword, would have preferred it for formal combat, and may have carried it even in battle.

The sieur de Grammont noted above had fought at least one duel long before becoming a buccaneer: he ran his sister’s suitor thrice through. Also among these French gentlemen-buccaneers were famous buccaneer-author Raveneau de Lussan; the sieur de Chauvelin who served under de Grammont aboard one of his consorts, a half-galley and who was killed in Florida in the aftermath of an aborted attempt on St. Augustine; and the sieur d’Hulot, a veteran of two campaigns against Algiers and the Algerine corsairs, and who would later command the regular French forces on Saint-Domingue. Alas, we have no record of any duels among these smallsword-wielding gentlemen, much less of any smallsword duels on the beach.

An interesting adoption of an army dueling practice was reportedly undertaken by Red Sea pirates circa 1693-94. According the deposition of pirate Samuel Perkins in 1698, fourteen pirates, variously from the crews of captains Thomas Tew, Josiah Raynor, William Mason, and Edward Coats, divided into two factions of seven each on St. Mary’s island some five years prior, “to fight for what they had (thinking they had not made a voyage sufficient for so many) and that one of the said Sevens were all killed, and five of the other, so that the two which survived enjoyed the whole Booty.”

What weapons were used is unknown, but cutlasses are likely. And the amount of booty? If this took place in the year 1693, Tew’s crew shared 1,200 pounds (the equivalent of 6,000 pieces-of-eight) per man, an extraordinary sum, making it unlikely any crew would fight to increase this — unless they had lost their shares gaming. Such losses might make desperate men even more desperate, willing enough to fight in a group duel in which most were likely to be killed. A year prior, the crew of Edward Coats shared 500 pounds per man, still a large booty and three or more times what would be considered a profitable voyage among the Caribbean buccaneers.

It was not uncommon for army regiments, particularly during winter quarters or in garrison, to settle conflicts this way, each choosing their best swordsmen to fight those of the other. Sometimes all fought at the same time, sometimes only one from each side would fight, the victor staying up to fight the next until defeated, then another would take his place.

Famous Scottish soldier, swordsman, duelist, fencing master, and prize fighter Donald McBane describes one such compound duel, its occasion being McBane’s theft of fourteen prostitutes from a Dutch regiment — the Scotsman had a profitable side gig of gambling and prostitution. The “next Day came Twenty-four Swords Men and Demanded the Lasses again, or else give them Satisfaction, we made up Twenty-four Men and Drank together; then we Fought two and two, there was Eleven of the Dutch Killed and Seven of our Men, our Bargain was, that if they beat us, we were to give them the Lasses and Pay them a Tribute, and on the contrary, they were to Pay us Tribute: We fought a Second Time, I being of the Royal it fell to me to Fight first, the first Time I was soon done, but the Second Time before I put I my Sword, I Fought Eight of them so it ended, and they promised to Pay their Tribute, we buried our Dead and parted…” But the Dutch didn’t pay, and shot four of the six men sent for the tribute two or three days afterward.

Early eighteenth-century pirates of the Black Flag reportedly fought duels with pistols ashore, to be followed by cutlasses if necessary, at least according to pirate chronicler and liar-when-convenient Charles Johnson (a pseudonym). The articles of Bartholomew Roberts and his crew reportedly provided that “The Quarter-Master of the Ship, when the Parties will not come to any Reconciliation, accompanies them on Shore with what Assistance he thinks proper, and turns the Disputants Back to Back, at so many Paces Distance: At the Word of Command, they turn and fire immediately, (or else the Piece is knocked out of their Hands:) If both miss they come to their Cutlashes, and then he is declared Victor who draws the first Blood.” Note that this quotation is from a secondary source, albeit a period one, not an primary source; no original examples of pirate articles from the 1714 – 1726 Black Flag era exist.

There were other methods of dueling with pistols during this era, and it is possible that pirates may have used some of them as well. For example, Donald McBane describes a form of pistol duel in which a cloak is held up in each duelist’s left hand so that neither man can see the other, then on cue pistols are fired through the cloak.

One wonders at the description of pistol dueling — generally considered in the popular historical fiction mind to have been a deadly form of honor combat — engaged in first among the Black Sail pirates of Roberts’s crew, to be followed by cutlasses merely to first blood. This is in fact unsurprising: 19th century sources note that pistol duels were far less dangerous than sword duels, and this in an era in which pistols were more accurate than in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. One commentator wrote that only one in six pistol duelists were wounded, and only one in fourteen killed. In sword duels, one or both duelists were nearly always wounded or killed, although another commentator noted that pistol wounds were usually far more dangerous than sword wounds. Pistol dueling grew in popularity as a means of showing one’s “bottom” aka courage, yet it was less dangerous by far than sword duels (unless one got shot), at least until the development of the epee de combat and light Italian dueling sabre in the late 19th century, much of whose swordplay and design were intended to minimize the risk of fatal wounds in an era in which dueling remained popular yet the law had begun to severely punish dueling’s most severe results.

Notably, in spite of their romance and implied associated courage, all forms of dueling were less dangerous than the battlefield of sea or shore.

Charles Johnson describes an early 18th century challenge and its aftermath among pirates. Assuming he is telling the truth, the bosun of Captain Evans, a pirate, challenged his captain to a duel with sword and pistol “on the next shore they came to.” Unsurprisingly — challenges are easy, following up on them much more difficult — the bosun declined to fight, for which Captain Evans caned him. The bosun in turn shot him through the head and leaped overboard to swim ashore but was taken up by the pirates. For this murder the pirate crew resolved to torture the bosun, but the gunner, inflamed with passion, shot him through the body instead. The bosun, not killed, begged a week for repentance. He “should repent and be damned to him,” said another pirate, who then shot the bosun dead.

Thus ends our brief foray into the reality of piratical duels on the beach. As I close this latest blog post, here’s something to note: duels in film and fiction must be exaggerated in order to keep the viewer or reader’s attention. Not so with reality: even a simple, short duel is exciting for the simple reason that real bloodshed is likely.

N. B. The captions at the foot of the first image above read “Outside parry with the forte” & “The thrust made against those who raise their sword when parrying.” The latter thrust would be typically made if the adversary delays the riposte, or as a “high-low” feint attack. Many period masters would disagree with the extension of the un-armed hand, preferring to keep it by the head, ready to parry or oppose.

Copyright Benerson Little 2024. First published August 20, 2024. Last updated September 23, 2025.

Jack Sparrow, Perhaps? The Origin of an Early “Hollywood” Pirate, Plus the Authentic Image of a Real Buccaneer

The small caption reads “Cover Drawn and Engraved on Wood by Howard McCormick.” Author’s collection.

The illustration above was created in late 1926 or early 1927, and published in April of the latter year. Among its several pirate clichés (skull and bones on the hat, tattoos, curved dagger, long threatening mustache) is one I had thought was entirely modern: a pirate hair braid with coins attached.

Quite possibly, this coin braid is the artist’s idea of a pirate “love lock.” The love lock was popular among some young English and French gentlemen in the first half of the seventeenth century. Usually worn on the left side, it was typically tied with a ribbon, a “silken twist” as one author called it. Occasionally two were worn, one on each side as in the image below.

Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt (1601-1666), known as “le Cadet la Perle” due to his bravery in battle. He is also sporting a pair of love locks. Print by Nicolas de Larmessin, 1663. British Museum.

This “pirate love lock” is a noteworthy characteristic of the very Hollywood, very fantasy pirate Captain Jack Sparrow, and I wonder if this image did not inspire much of his look. Historically-speaking, though, there is no historical basis for it among pirates of the “Golden Age” (circa 1655 to 1725), although it’s possible there may have been a gentleman rover or two who wore one during the first half of the seventeenth century–but not a braid or lock with coins.

Of course, much of The Mentor pirate image above was clearly inspired by famous illustrator and author Howard Pyle, as shown below.

Romantic, largely imagined painting of a buccaneer. From “The Fate of a Treasure-Town” in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1905. The image is reprinted in Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

“How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas,” Howard Pyle, Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899, a special two-page image. I’ve discussed this image in Of Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar Smoking Women.

A classic Howard Pyle line drawing, from Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

There’s a hint of N. C. Wyeth too, not surprising given that he was a student of Howard Pyle. However, Captain Peter Blood was a gentleman pirate, and the pirate on The Mentor cover is clearly not.

Battered dust jacket from the photoplay edition of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini, 1922. The cover art and identical frontispiece artwork by N. C. Wyeth.

And Wyeth’s Captain Blood cover is clearly influenced by this 1921 cover he painted for Life magazine. In fact, less the goatee, the two buccaneers might be one and the same:

Details about the painting can be found at the Brandywine River Museum of Art. Oddly, the Life magazine issue has no story or article about buccaneers or pirates.

“The Pirate” by N. C. Wyeth. Pretty much the same pirate as immediately above, less the fictional “pirate boots,” this time painted for Hal Haskell Sr., a Dupont executive who commissioned it in 1929. For years the painting hung in Haskel’s yacht, and afterward to the present in the family home. The print is available from The Busacca Gallery, Art-Cade Gallery, and other vendors.

The Pyle influence continued through the twentieth century in film, illustration, and mass market paperbacks about pirates…

“Pirate Dreaming of Home” by Norman Rockwell, 1924. The painting is also clearly based on Howard Pyle’s famous painting, “The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow,” and may be intended to represent the same buccaneer later in life, or perhaps is simply an homage to Pyle. (Norman Rockwell Museum.)

The Mentor illustration is also clearly influenced by Douglas Fairbanks’s 1926 film The Black Pirate, which was, according to Fairbanks himself, heavily influenced by Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates and to a fair degree by Peter Pan.

Seriously, check out Fairbanks’s costume in the film, it’s obviously that of Peter Pan grown up. I have a soft spot for Douglas Fairbanks: my first fencing master, Dr. Francis Zold, described him as a gentleman and a swordsman, and described how Fairbanks invited the Hungarian fencers to his mansion Picfair (named after Fairbanks and his wife, Mary Pickford) after György Jekelfalussy-Piller won the gold saber medal at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games. (N.B. I think Dr. Zold was referring to Fairbanks Sr. as a gentleman and a swordsman, but a nagging itch in my mind suggests that it was Fairbanks Jr. instead.)

Anders Randolf as the pirate captain in The Black Pirate. Note the skull and bones on the hat, the dagger in the mouth, the hoop earring, and, just visible, the tattoo on the chest. Screen capture from the Kino Blu-ray. A useful review of the film is available here.

Publicity still, possibly a frame enlargement from B&W footage given the grain, of the admirable duel on the beach between Randalf and Fairbanks, choreographed by Fred Cavens. More on this in a later blog post. Author’s collection.

And here, finally, we have Johnny Depp as Jack Sparrow in the flesh, braids and such dangling from his hair, again for which there is no historical precedent among Golden Age pirates that we know of. It’s hard to see how Depp’s costume, in particular his hair, might not have been influenced by the illustration at the top of the page. If it weren’t, it’s quite a coincidence.

“Captain Jack Sparrow makes port” from the Jack Sparrow Gallery on the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean website.

Jack Sparrow again, with a closer look at his braids &c. from the Jack Sparrow Gallery on the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean website.

As noted, it’s entirely possible that the Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl costume designers never saw the image at the top of the page. They may have imagined it themselves, or been influenced by something else. A very likely possibility is Donald O’Connor in the 1951 film Double Crossbones, a campy pirate comedy that makes fun of nearly all pirate clichés.

Donald O’Connor in Double Crossbones. Note the braid over his right ear. (Screen capture.)

Although this may seem to be little more than coincidence, there are other similarities between the two films, strongly suggesting the writers and costume designers were familiar with it. In particular, O’Connor plays a shy, somewhat bumbling shopkeeper’s apprentice in love with the governor’s beautiful ward, and she with him. Due to difference in social class he’s unwilling to express his love openly until by accident he becomes a pirate. Sound familiar? Even the costumes of the governor’s ward (Lady Sylvia Copeland, played by Helena Carter) are similar (homage-fashion?) to those of Elizabeth Swann, played by Keira Knightley. If not the Pirates of the Caribbean costume designer, then perhaps the Double Crossbones costume designer was familiar with the image at the top of the page.

Screen captures from Double Crossbones, 1951. Plenty of candlesticks, not to mention a painted miniature around the neck instead of a magical Aztec coin.

And there’s another film possibility: Torin Thatcher (a pirate’s name if ever there were!) as Humble Bellows in The Crimson Pirate (1952). Bellows wears a love knot, perhaps to compensate for his balding pate. It’s surely better than a comb-over! Disney may have been inspired by Bellows’s coiffure, for, like Double Crossbones above, there are numerous homages, shall we say, to the film in the Disney franchise, ranging from the way soldiers march to the “walking boat underwater” scene. It’s also possible that Donald O’Connor’s ‘do inspired Bellows’s.

Torin Thatcher as Humble Bellows in The Crimson Pirate (1952). Blu-ray screen capture.

Of course, all this so far is “Hollywood,” for lack of a better term. There are a number of serious groups of reenactors, scholars, and others trying to correct the false historical image, all with varying degrees of accuracy, agreement and disagreement, and success.

Hollywood has yet to get aboard, no matter whether in pirate films and television series, or often any film or television set prior to the nineteenth century for that matter, probably because it’s easier to play to audience expectations (and, unfortunately, much of the audience doesn’t really care), not to mention that there’s a tendency or even a fad among costume designers to do something that “evokes” the image or era rather than depict it accurately, not to mention the time and other expense of researching, designing, and creating costumes from scratch when there are costumes “close enough,” so to speak, already in film wardrobes.

Here’s a hint, Hollywood: you can start by getting rid of the “pirate boots.” They didn’t exist. They’re actually based on riding boots, and a pirate would only be in riding boots if he were on a horse–and horses aren’t often ridden aboard ship. Further, you can get rid of the baldrics in most cases, exceptions being primarily for gentlemen pirates wearing smallswords into the 1680s, no later. (You can have some Spanish pirates with rapiers wear baldrics after this, though.) And for that matter, you can get rid of wide belts and large belt buckles too. But if nothing else, please, please get rid of the boots, which, if I recall correctly, a UK journalist once correctly described as nothing more than fetish-wear.

Full disclosure: I was the historical consultant to Black Sails, a great show with a great cast and crew, but I had nothing to do with the costuming, much of which is considered as near-blasphemy by advocates of historical accuracy in material culture in television and film. That said, the show is a fictional prequel to a work of fiction that variously created or expanded some of our biggest myths about pirates–buried treasure, the black spot, and so on. Looked at this way, if you can accept the story you can probably tolerate the costuming.

I’ve discussed what real pirates and buccaneers looked like several times, not without some occasional minor quibbling by other authorities. The Golden Age of Piracy has some details, as do two or three of my other books, but several of my blog posts also discuss some of the more egregious clichés, with more posts on the subject to come.

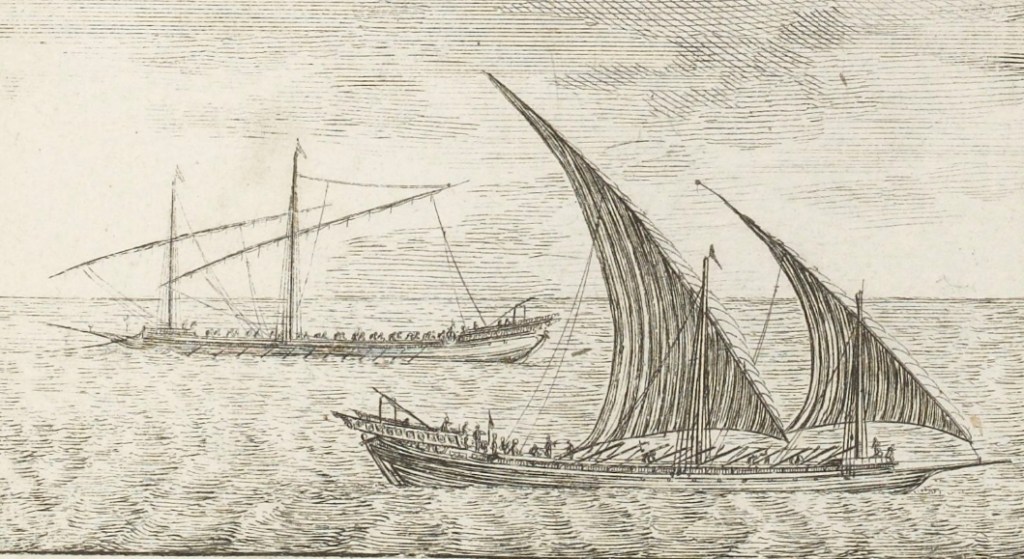

At any rate, here’s an image of a real buccaneer, a French flibustier in fact, from the 1680s. It’s an eyewitness image, one of only a handful of authentic eyewitness images of “Golden Age” sea rovers. It and the others prove that an image may evoke swashbuckling pirates while still being entirely accurate.

One of several eyewitness images of French flibustiers (buccaneers) in the 1680s. These are the only known eyewitness images of Golden Age sea rovers. They went largely unnoticed and without commentary until I ran across them by accident while researching late 17th century charts of French Caribbean ports. I’ve discussed them in an article for the Mariner’s Mirror, and also in these two posts: The Authentic Image of the Real Buccaneers of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini and The Authentic Image of the Boucanier. The posts include citations to the original images.

Copyright Benerson Little 2018. First published January 23, 2018. Last updated April 4, 2018.

Did Pirates Wear Eye Patches?

Costume illustration of an eye-patched, peg-legged seaman by Paul Gavarni for the Carnival in Paris. The popular image–trope, if you prefer–of the disabled seaman had been in place for more than a half a century by now, if not longer, in both Britain and France. This image was created between 1838 and 1843. British Museum.

So, “Did pirates wear eye patches?”

The short answer: Only if they had lost eyes to disease or injury, and this was no more prevalent among pirates than among fighting seamen and soldiers. In other words, the eye patch is in no way a sign or symbol of the pirate per se, nor even of the seaman in general.

Still, the question is a good one, if only to give us a reason to dig into related history.

The Mythbusters television show and other speculators have recently added to the myth by working backward from the proposition, that is, “If pirates wore eye patches, why would they have worn them?” rather than looking first at primary sources to see if there is any evidence that pirates wore them at all. There isn’t, other than as noted below.

The associated suggestions that pirates may have worn eye patches to improve night vision or daylight lookout observations or to enable them to fight below decks isn’t supported by any primary source material. In fact, the loss of sight in an eye, even by wearing an eye patch, causes significant loss in both depth perception and visual breadth, making movement aboard a vessel, aloft especially, very dangerous. It would also make visual observation by a lookout much more difficult.

As for fighting below decks, pirates and other seamen didn’t really do much of it: it was much easier to flush crew below decks by tossing grenades and firepots into breaches chopped into decks and bulkheads with boarding axes. In other words, the mere idea that eye patches might have been used to aid in fighting below decks shows a clear lack of understanding of the subject.

In other words: There is no historical evidence at all for any of these purported reasons why a pirate might have worn eye patches! Mythbusters and other popular “documentaries” are entertainment, not serious history. This includes “The History Channel,” now known I think as History.com: it’s “docu-tainment,” not real history. Trust me on this: if you’re being interviewed as an expert for a TV “documentary” and produce too many facts against the episode’s premise, the producers won’t put you on screen!

Again, let me emphasize: if a pirate wore an eye patch it was because he had lost an eye or was disfigured in his eye, and for no other reason!

The origin of the modern myth that pirates wore eye patches is largely literary. However, its roots lay deep in reality, both in the fact that eyes were often lost to disease and battle trauma, and that a one-eyed person often looks fearsome or sinister. The latter sense goes back millennia, and probably farther. Homer’s Cyclops, Polyphemus, is an early instance.

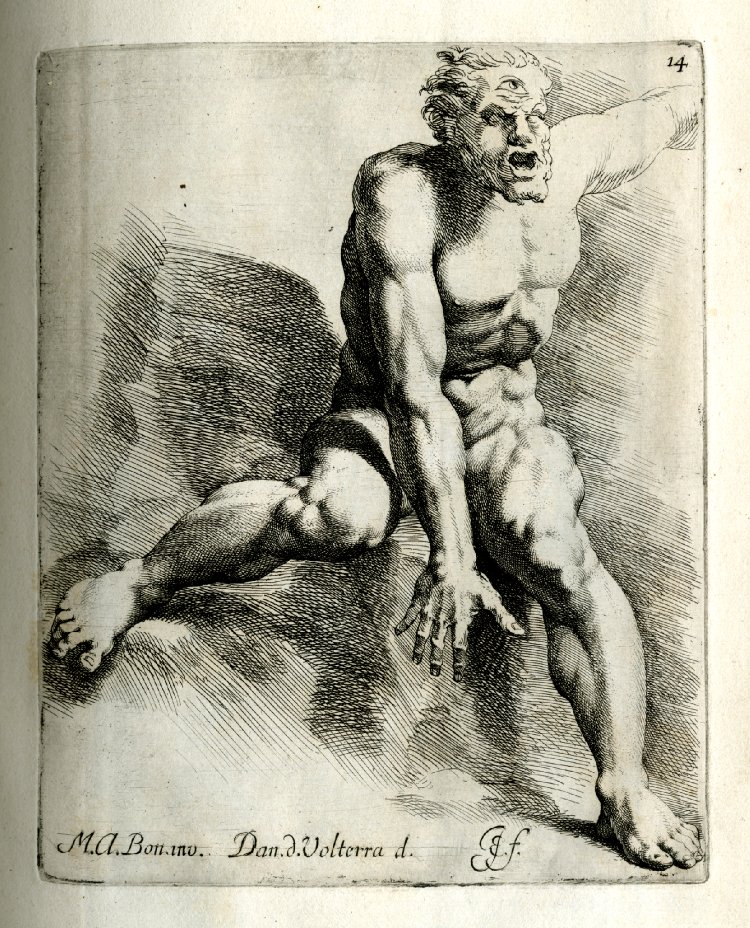

Polyphemus by Jan de Bisschop, after Daniele da Volterra, after Michelangelo, after Pellegrino Tibaldi, 1671. Odysseus, aka Ulysses by the Romans, blinded him. British Museum.

Some versions of Bernal Diaz’s The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico describe the fierce old musketeer Heredia, sent to frighten Native Americans, as a one-eyed, one-legged (or game-legged) soldier. The same work describes how Cortez’s enemy, Narvaez, lost an eye in battle.

A British army pensioner with eye patch and wooden leg. Again, the image was not restricted to naval seamen, much less, and popularly, pirates. By Isaac Robert Cruikshank, late eighteenth or early to mid-nineteenth century. British Museum.

Among seafaring journals and other records of the Golden Age of Piracy, there is only occasional mention of one-eyed seamen, usually in lists of those wounded in battle. Exquemelin’s various editions of The Buccaneers of America famously list compensation for the wounded, including the loss of an eye, and it is here that the primary source of the myth of pirates and eye patches is probably to be found, in combination with other works such as Bernal Diaz’s. The loss of an eye in battle was fairly common, in fact: seafarer Edward Coxere describes the use of oakum and tallow to stuff an eye socket in order to heal the wound, for example. Notably, none of the several eyewitness images of buccaneers or flibustiers from the 1680s show any with any of the usual Hollywood characteristics: wooden legs, eye patches, parrots, hooks, &c. This is to be expected. The large number of images of seamen, usually naval, with eye patches dates to a century later.

Images of splinters produced by round shot during an accurate test of the damage done in action. Author’s photos taken at the Erie Maritime Museum.

As a friend, “Tweeds Blues,” pointed out recently, it seemingly would not be surprising to find a fair number of one-eyed naval, privateer, and pirate seamen, given the damage done by splinters in action. Here I feel the need to point out yet again that Mythbusters is entertainment: one episode even suggested that splinters didn’t cause much damage in a naval action. In fact they did: there are hundreds, if not thousands, of accounts of the damage done, not to mention at least one accurate test that proves the horrible extent of damage splinters can do. The Mythbusters test parameters were simply incorrect, not to mention that overwhelming historical evidence was largely ignored, as were previous–and more accurate, historically correct–tests. The images above show splinters resulting from round shot striking a correctly-built hull section. The test was conducted by the Maritime Museum in Erie, Pennsylvania, home of the Flagship Niagara.

Admiral Don Blas de Lezo y Olavarrieta. Blas de Lezo is best-known for successfully defending Cartagena de Indias against British attack in 1741. Injuries received during his naval career included the loss of an eye, his left hand, his left leg below the knee, and the laming of his right arm. Museo Naval, Madrid.

Joseph Burgin, a Greenwich pensioner, who lost and eye and a leg in action in the Royal Navy in the early eighteenth century. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Of course, the most famous example of a naval mariner with an eye patch is arguably, at least in the UK and probably the US, that of Lord Admiral Horatio Nelson, who lost the sight in one eye during the capture of Calvi on Corsica in 1793–except that did not actually wear an eye patch. This has not stopped the popular assumption that he did from becoming prevalent, and, although out of our period, this has still influenced the idea of the one-eyed mariner, and therefore one-eyed pirate. Admiral Nelson also lost an arm. Some would argue, at least in the Hispanic world, that Bras de Lezo (second image above) is the most famous eye-patched admiral.

“Portret van Johann Karl von Thüngen,” the German field marshal. Period images of him show this eye patch worn without a thong, string, or other tie. Anonymous, 1675 – 1711. Rijksmuseum.

The fact is, patches were commonly used to cover any facial disfigurement. In the seventeenth century diarist and navy secretary Samuel Pepys wore a black patch, or possibly a large beauty patch, to cover a large cold sore. Similarly, King William III advised a soldier to remove the black patch covering the scar on his face because “It’s more honourable in a Soldier to wear a Scar than a Patch.” (For the latter reference, see Coke in the sources listed below.)

Scottish soldier Sir William Brog, 1635, with a patch covering a scar on his nose. (And an earring too.) Pring by Crispijn van Queborn. British Museum.

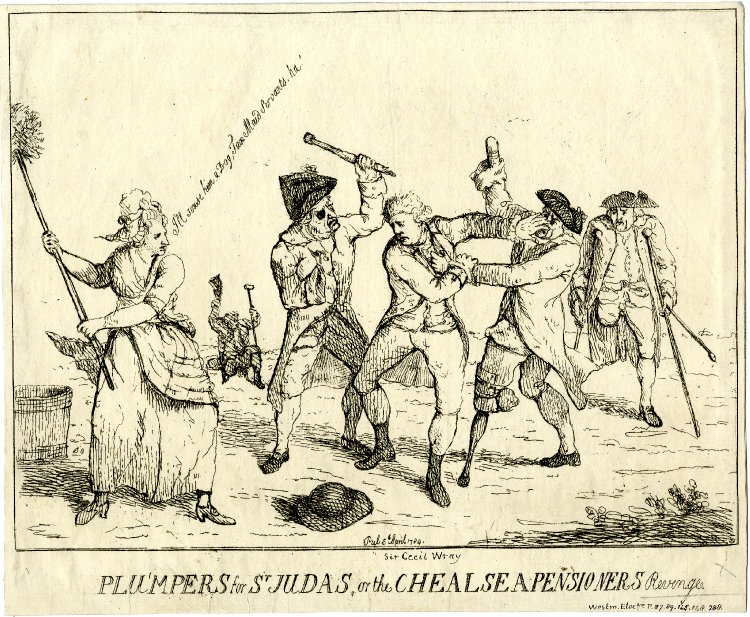

Eye patches, stumps aloft and ‘alow, not to mention peg legs. “Plumpers for Sr Judas, or the Chealsea Pensioners Revenge,” a satirical print, 1784. British Museum.

By the late eighteenth century the image of the eye-patched, peg-legged seaman was iconic, probably the result of the increased number of British naval actions brought on by the American Revolution and, especially, the Napoleonic Wars. Notably, in reality most such disabled seamen were pensioned from service, as shown above. These satirical images are probably the material origin of the popular identification of the naval seaman, and therefore the pirate, with eye patches.

Even with its legitimate historical roots in fact, this pirate myth, like many, didn’t come fully into being until the mid-nineteenth century, a hundred or more years after the Golden Age of Piracy. Sir Walter Scott in The Fortunes of Nigel describes “The noble Captain Colepepper, or Peppercull, for he was known by both these names, and some others besides, had a martial and a swashing exterior, which, on the present occasion, was rendered yet more peculiar, by a patch covering his left eye and a part of the cheek. The sleeves of his thickset velvet jerkin were polished and shone with grease, — his buff gloves had huge tops, which reached almost to the elbow; his sword-belt of the same materials extended its breadth from his haunchbone to his small ribs, and supported on the one side his large black-hilted back-sword, on the other a dagger of like proportions.” Here is the epitome of the swashbuckler, easily translated to the pirate.

The bold and swaggering Captain Colepepper, from The Fortunes of Nigel by Sir Walter Scott. Nineteenth century, unknown edition.

Not long after, Charles Dickens described a pirate with “the one eye and the patch across the nose” and soon afterward similarly did many writers of popular fiction. However, many of our principle originators or propagators of pirate myths—Robert Louis Stevenson, J. M. Barrie, N. C. Wyeth, for example—do not appear to have bothered with this myth, although Barrie’s Captain Hook probably did encourage other images of pirates missing a vital part such as a limb or eye, and Howard Pyle in The Ruby of Kishmoor equips a pirate, one of the four in the short tale, with an eye patch.

In 1926 Douglas Fairbanks propagated nineteenth century pirate myths, as well as a few he helped create, across the world with his film The Black Pirate. In it he established the modern pirate swashbuckler stereotype, based much on Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates, Peter Pan, and probably Captain Blood (one of whose characters, by the way, was one-eyed, although he lost the eye at Sedgemoor, not at sea). Around the same time, we begin to see pirate book cover art and other illustrations showing pirates with eye patches. But it would take later films, such as The Black Swan and The Crimson Pirate to make the eye patch an obvious, routine part of the stereotypical pirate costume.

Publicity still from The Black Swan, 1942. An eye-patched Anthony Quinn is on the right.

Sources

Roger Coke. A Detection of the Court and State of England. 4th ed. London: J. Brotherton and W. Meadows, 1719. Vol. 2:472.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España. Reprint, Madrid: Don Benito Cano, 1795. See vol. 1:213.

Edward Coxere. Adventures by Sea of Edward Coxere. Edited by E. H. W. Meyerstein. London: Oxford University, 1946.

Charles Dickens. “The Perils of Certain English Prisoners.” 1857. Reprinted in Charles Dickens’s Stories from the Christmas Numbers. New York: MacMillan, 1896. Page 144.

Alexandre Exquemelin [John Esquemeling]. The Buccaneers of America. London: Crooke, 1684. Reprint, New York: Dorset Press, 1987. Page 60.

Benerson Little. The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016. Prologue.

——. “El Mito Pirata” in Desperta Ferro 17 (August 2015), 52-55.

Heidi Mitchell. “Does Reading in Dim Light Hurt Your Eyes?” Wall Street Journal online, April 8, 2013, http://www.wsj.com.

Mythbusters, Episode 71.

Samuel Pepys. Diary. September 26, 1664.

Walter Scott. The Fortunes of Nigel. Boston: Samuel H. Parker, 1822. Page 255.

The Telegraph. “Nelson didn’t wear eye-patch, says historian.” January 19, 2005.

Copyright Benerson Little, 2017. Last updated August 14, 2025.

The Authentic Eyewitness Image of the Real Buccaneer

The dashing image in the banner above–in which Peter Blood’s posed-for-the-camera attack has been parried by the equally posed Captain Levasseur, and Blood needs to recover quickly before he finds a blade in his eye or his belly–is taken from an original publicity still for Captain Blood, 1935, starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone. The film duel between Flynn and Rathbone, of clashing swords on California sand, is without doubt the most iconic of Hollywood sword fights, and although it has often been imitated, the results have almost never been quite as satisfactory. Certainly no other film “duel on the beach” is so evocative.

Therefore, in view of the foregoing, not to mention my long admiration for both the novel by Rafael Sabatini and its film version directed by Michael Curtiz, and as much for fun and nostalgia as for education, I’ll spend my first dozen or more blog posts working my way through authentic, literary, and film swordplay among pirates, with occasional associated digressions.

However, before we draw swords and explore the myth and reality of fencing with “sharps” among pirates and others, we’ll consider what the seafaring thieves of the 1680s Caribbean actually looked like, and how they were armed. Was this anything like Sabatini or Curtiz represented them? Was it anything like illustrators and Hollywood artists—Howard Pyle and Douglas Fairbanks, for example, whose works have come to define the image of the buccaneer—dressed them up and showed them off?

Fanciful illustration, “The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow,” by Howard Pyle, from “The Fate of a Treasure-Town” in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1906. Reprinted in Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

To begin, we require a few definitions. With a few exceptions, most of the Caribbean sea rovers from 1655, when England piratically seized Jamaica from Spain, to 1688, when Europe went to all out open war, existed in a gray area between legitimate privateering and outright piracy. At times these sea rovers had legitimate commissions, at times a mere “wink and a nod” from local authority, and at times no commissions at all, or forged ones, or falsely extended ones. In all cases these rovers eschewed the term pirate for two reasons: first, piracy was a hanging offense, and second, they considered themselves as something better than common pirates. After all, they not only attacked well-armed Spanish ships at sea, but they also, in military order, sacked Spanish towns.

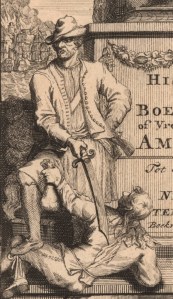

A somewhat more accurate illustration of a buccaneer threatening a Spanish prisoner, from the frontispiece to Exquemelin’s Historie der Boecaniers, of Vrybuyters van America, 1700. (John Carter Brown Library.)

Their preferred terms were, among the English-associated rovers, privateer and buccaneer. The former proclaimed their legitimacy, the latter their unique place. The term buccaneer derives from boucanier, the term for the French cattle and swine hunter of Hispaniola, which derives from boucan, a Tupi word meaning grill or grate for cooking and smoking meat and fish. (Similarly, barbecue derives from the Spanish barbacoa, which derives from the Taino word for the grill or grate.) The French-associated rovers, on the other hand, used the term flibustier, which, as far as we can tell, originated with the Dutch vryjbuiter, which was anglicized via a pretty much direct translation as freebooter, which the French adopted as fribustier and flibustier, which was later anglicized as filibuster. Occasionally the French used the term aventurier, or adventurer, which accurately reflected the men drawn from all walks of life to the trade. (For eyewitness images of boucaniers, go here.)

From a number of eyewitness written descriptions we have a pretty good idea what these buccaneers and filibusters looked like, or at least enough of an idea to make some reasonable conjectures. Unfortunately, lacking archaeological evidence, we are likely to make some mistakes.We cannot even rely on period illustrations in first-hand accounts about buccaneers, for it is almost certain that the illustrators never saw their subjects. The only exception may be the illustrations of Henry Morgan, who is likely, given his fame, to have sat for a portrait in London while there after sacking Panama.

Worse, fiction, popular illustration, and film have corrupted our idea of what these gentlemen of semi-legitimate fortune may have looked like, as in the case of Howard Pyle’s romantic image above. Therefore, rather than provide several written descriptions first and speculate from them, we’ll cut to the chase and see with our own eyes exactly what Captain Peter Blood’s buccaneers and filibusters really would have looked like.

It turns out that in the archives of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) and the French Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer (ANOM), are a couple dozen charts of French Caribbean ports, primarily those of Saint-Domingue on Hispaniola, made during the 1680s by French engineers. In other words, these are charts rendered by eyewitnesses. And in the cartouches of a fair number are detailed eyewitness drawings of filibusters and boucaniers, as well as of the occasional common worker, probably an engagé (indentured servant), and the occasional slave.

I discovered these by accident a few years ago. I wasn’t the first to do so, but I was, as far as I know, the first to analyze some of them in detail and publish the results (Mariner’s Mirror, August 2012). Their significance had been almost entirely overlooked. For me, the discovery made me feel as if I had briefly traveled back in time—and left me disappointed I could not remain at least for a while.

And here’s why! In this first image, we see a pair of buccaneers or flibustiers at Petit Goave on Saint-Domingue, the western half of Hispaniola claimed by the French. By the 1680s Petit Goave had replaced Tortuga as the sea roving port on Saint-Domingue, and was populated by a large number of flibustiers of several nationalities, colors, and ethnicities.

A pair of flibustiers or buccaneers at Petit Goave, 1688, from a chart by P. Cornuau. (Courtesy of the Archives Nationale d’Outre-Mer.)

The buccaneer on the left is armed with long-barreled fusil boucanier, or “buccaneer gun” in English, the common weapon of the Caribbean sea rover. He wears a large cartouche box at his left front, and a cutlass at the side behind it. We can assume from his scabbard that his cutlass is, like his companion’s, made with a clip point, a common style during the era. His hat is small-brimmed, turned up on the left side, and appears to have a small plume. He wears a stylish cravat. His coat is fairly long, and short-sleeved with large cuffs. He may be wearing a sash over it. His stockings are conventional and worn over the knee as was the practice at the time, and his shoes are conventional with short tongues.

His swashbuckling companion is armed with a cutlass whose hilt, given its style, is probably of brass. He likewise wears a large cartouche box at the left front. His hat is broad-brimmed with a large plume, and is turned up at the front. He appears to wear a cravat. His jacket is shorter, with two rows of buttons, short sleeves with cuffs (or rolled up sleeves), and he has a sash tied around his waist, almost certainly with a belt over it to hold cartouche box and cutlass. He wears seaman’s breeches, possibly un-gathered, with stockings that appear to be worn over the knee. His shoes are conventional. It’s impossible to know if they are buckled or tied.

A buccaneer or flibustier at Île-à-Vache, 1686, from a chart by P. Cornuau. (Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

Next we have a couple of flibustiers or buccaneers drawn at Île-à-Vache, a common rendezvous off the southwest coast of Hispaniola. Our buccaneer on the right is armed with a fusil boucanier, as most were. The musket is correctly depicted at half-cock, and the deep notch at the neck is the sort later known as “female.” His large cartouche box is worn at the left front over a sash and certainly on a belt. His jacket is short, with large cuffs. His wide, probably open breeches are those of a seaman. His shoes common, his hat broad-brimmed and with a plume. He may have a mustache, and, notably, his hair is shoulder-length and loose. Many seamen–and buccaneers were a combination seaman and soldier–wore their hair tied back or in a queue so that it would not get in their faces or get drawn into a block. But at least among the buccaneers and flibustiers, this rule did not always apply.

Flibustier or buccaneer at Île-à-Vache, 1686, from a chart by P. Cornuau. (Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

At the left is another buccaneer and his fusil boucanier, again correctly at half-cock, along with his typical large cartouche box–commonly holding thirty-six cartridges–at the left front. He has a cutlass, although all that’s visible is the scabbard on his right side, making him left-handed. Again, the cutlass is clip-pointed. His hat is turned up at the right side, with a plume on the left, although it’s possible the hat is actually a boucanier’s cropped hat (see next blog post). Like the previous buccaneer, his jacket is short, but with smaller cuffs. His shirt has a bit of lace at the cuffs, and he wears a cravat. His stockings are secured at the knee, and his shoes common, apparently with short tongues.

In the image below, made by “Partenay” aboard the small French man-of-war Le Marin in 1688, we can compare illustrators for accuracy. It depicts two aventuriers, the one on the left possibly a boucanier, given the wild pig at his feet, although he may in fact be a flibustier (boucaniers often accompanied flibustiers, and some men went back and forth between the trades), and the one on the right probably a flibustier. Both men wear fairly broad-brimmed hats turned up at the front, and both wear what are probably wide seaman’s breeches, but similar garments–caleçons of linen or canvas, often open at the knee–were common to boucaniers, indentured servants, and others. Both men have loose shoulder length hair. The hunter or flibustier on the left wears a common shirt, large and loose, and appears to have a cravat or kerchief at the neck and tucked into the shirt. The fusil boucanier is of the “club butt” style which, at least in the eighteenth century, came to be the most common. Note the short clay pipe smoked by the flibustier on the right.

Boucanier and buccaneer, or two buccaneers, at the French sea rover haven of Petit Goave in 1687 or 1688, drawn by Partenay in 1688. (Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

In the image below, again by Cornuau, we see a flibustier with two captured Spaniards in chains. He is armed with cutlass with a small shell or shells, and a strongly curved blade with a clip-point. His scabbard hangs from a sword belt common to the period, that is, with two straps, with loops at the end, hanging from the belt. His large, obviously thirty round, cartouche box is on his right side, perhaps an illustrator error, perhaps personal preference. He wears a short, perhaps crude jacket, probably of osnabrig canvas or sackcloth. He also wears wide seaman’s breeches, as many of his associated do. His head covering is a boucanier cropped hat, and his footwear is a pair of crude boucanier shoes made of raw pigskin cut from pig hocks. This footwear seems common among flibustiers, and may be what Father Avila meant when referring to pigskin shoes among the flibustiers. (See also The Authentic Image of the Boucanier for more details on these shoes.)

Flibustier with captured Spaniards in chains. From the French chart “Carte particulière de la rivière de la Plata” by Paul Cornuau, probably 1684 based on a nearly identical chart he drew of the River Plate dated 1684.

These buccaneers or filibusters are probably dressed as they commonly were, particularly ashore in their own ports. The arms they bear in the images above are also largely what they would use during attacks at sea, even during boarding actions against ships whose crews had retreated to closed quarters: even here the musket had its uses. It was less useful, of course, in hand-to-hand action on open decks. Common arms used during attacks on ships were the musket to suppress enemy fire and pick him off, as well as to engage enemy loopholes in closed quarters; the cutlass and pistol for close combat; the boarding ax, often along with a hand-crow, for chopping into decks and bulkheads in order to breach closed quarters (and it from this purpose that the boarding ax gets its name); the cartridge box for reloading musket and pistol; and the grenade, fire-pot, or stink-pot for destroying men in the open on deck, and particularly for tossing into breaches made in closed quarters, in order to flush the enemy out or otherwise force him to surrender.

What we do not yet see are these sea rovers fully dressed and armed for an attack on a Spanish town–but Caruana, the creator of most of the charts that interest us, does not disappoint. He provides us with an iconic image of a buccaneer or flibustier fully equipped for an attack ashore! Beginning with his clothing, he wears a broad-brimmed hat. His hair is either short, or more likely, tied at the back. His jacket is moderately long, his belt narrow (as are all those in these images, not the wide Hollywood belts for these flibustiers), his breeches conventional, not of the sort commonly worn by seamen. He may or may not be wearing stockings: if his shoes are those worn by boucaniers (see next blog post), then he wears no stockings.

But it is his armament we are most interested in. He has a fusil boucanier over his shoulder, again at half cock. In his left hand is a paper cartridge which would hold both ball and powder, and sometimes seven or eight swan shot on top of a single ball, and power. The cartridge had been early adopted by boucaniers and flibustiers, and they learned early the lesson that conventional armies would learn after them: that the flintlock with cartridge was the most efficient weapon for campaigning, and, eventually, for conventional warfare.

At his waist is a cutlass, this one with an obvious brass hilt given its shape, and without a clip point as can be discerned by the shape of the scabbard and its chape. He has a cartouche box on his belt, again on the left front, and on his right front is a single pistol. Notably, its lock is against his body (this would help protect the lock), with the butt to his left for an easy draw. I’ve tested this way of carrying a pistol: it works well with small to medium pistols, although large pistols (12″ and longer barrels) are easier to carry putting the belt-hook on the inside, with the pistol hanging on the outside, although the pistol is less secure this way. With two pistols, one would be carried on the left side, the other left-front, assuming a right-handed shooter.

This setup is well-balanced: cutlass and cartouche box on one side, pistol (often a pair) on the other. At Veracruz flibustiers were noted as carrying two cartouche boxes: the second was probably worn at the back, and carried additional cartridges, most of which were almost certainly for use with the musket, the buccaneer’s primary weapon according to buccaneer and surgeon Alexandre Exquemelin. In our flibustier’s right front pocket is a small powder horn, almost certainly for re-priming the pan as necessary. Buccaneers primed from the cartridge as they loaded, but would require a horn to re-prime if, for example, the powder in the pan got damp.

Two more details deserve attention. First, above his belt is a thin cloth that serves as a mosquito netting. Such netting is described in at least three eyewitness sources. It was usually worn around the waist or over the shoulder like a bandoleer. Second, around his neck is a detail almost never seen: a musket tool used variously, depending on the tool, for clearing the vent, chipping a dull flint to get another shot or two before it must be changed out, tightening the cock, as well as other tasks associated with cleaning and maintaining a musket.

There exist substantial written evidence to support these images. Father Jean-Baptiste Labat has described the flamboyant dress of flibustiers, especially after pillaging a ship’s cargo (a scene that may well have inspired a similar scene in Frenchman’s Creek, 1944). The arms of the flibustiers–fusil boucanier, cartouche box, one or two pistols, a cutlass–are described several times by eyewitnesses. What we have not had is this eyewitness corroboration in the form of images.

We also have an eyewitness account by one of the victims of a buccaneer attack, in this case the brutal rape and pillaging of Veracruz in 1683, of which I will speak more of in a later blog. The account adds details we have hitherto lacked. According to Fray Juan de Avila, the flibustiers wore “sailcloth jackets, shoes of cowhide but more wore those of pigskin [possibly cheaper shoes, or even those the boucaniers commonly wore, or both], and others wore jackets of blue sackcloth [possibly dyed with indigo from Saint-Domingue]” and were armed with “a cutlass, a large (or long) flintlock musket [clearly a buccaneer gun], two pistols, and hanging from a waist belt two cartridge boxes with paper cartridges inside…”

In sum, these buccaneers or flibustiers are much as we imagined them: picturesque and picaresque, a combination of Hollywood and reality long before Hollywood ever existed. But note what we do not see: no peg legs (extremely rare in reality, for they make buccaneering difficult), no eye patches except due to injury (absolute myth created by literature and illustration and unfortunately further spread by Mythbusters, &c.), few obvious tattoos (some men and women, not just seamen, had a few but not to the degree we like to believe), no insignia of skull and bones (although some may have worn mortuary rings with such symbolism, as did people from all walks of life), no earrings (although foppish pirates may have worn them on occasion, and Dutch seamen, along with many Dutch in general, did wear them), and no parrots–although some pirates did in fact keep parrots, although more often than not probably as plunder. Also, please note that none wear boots. Fishermen wore boots at times, seamen in arctic waters did too, but otherwise, seamen, including sea rovers, did not. Worse, the boots we see pirates in film, television, and illustration wear are riding boots–and one doesn’t ride horses aboard ship.

I will get to discussing swordplay soon enough, but the next blog post will describe in similar detail the dress and arms of the boucanier, of the cow and pig hunters who often accompanied flibustiers on their attacks at sea and ashore.

Bibliography

Avila, Juan de. “Pillage de la ville de Veracruz par les pirates le 18 mai 1683 (Expedition de Lorencillo).” Amoxcalli manuscript no. 266, http://amoxcalli.org.mx/paleografia.php?id=266.

Captain Blood. Warner Brothers Pictures, 1935.

Cornuau, Paul. “Carte particulière de la rivière de la Plata.” Probably 1684. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan des passes et du bourg du levé et dessigné par ordre de Mr. De Cussy, Gouverneur pour le Roy de l’isle de la Tortue et coste St. Domingue.” 1685. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan du Cap et de son entrée,” 1684. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan Ignographique du Fon et de l’Isle à Vache,” 1686. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan ignographique du Fon et de l’Isle à Vache,” 1686 (second chart bearing this title). Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

——. “Plan du Petit Goave et de l’Acul, avec le Figuré du Fort du Petit Goave tel qu’il a été Reformé, avec Deux Autres Plans de ce Même Fort.” Circa 1688. Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer.

Exquemelin, A. O. [Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin]. De Americaensche zee-roovers. Amsterdam: Jan ten Hoorn, 1678.

——. Bucaniers of America. London: William Crooke, 1684.

—— [Alexander Olivier O’Exquemelin]. Histoire des avanturiers qui se sont signalez dans les Indes. 2 vols. Paris: Jacques Le Febure,1688.

——. Historie der Boecaniers, of Vrybuyters van America. Amsterdam: Nicolaas ten Hoorn, 1700.

——. The History of the Bucaniers. London: T. Malthus, 1684.

——. Piratas de la America, y luz à la defensa de las costas de Indias Occidentales. Translated from the Dutch by Alonso de Buena-Maison. Cologne: Lorenza Struickman, 1681.

Labat, Jean Baptiste. Nouveau Voyage aux Isles d’Amerique. 6 vols. Paris: Guillaume Cavelier, 1722.

Little, Benerson. The Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish Main, 1674–1688. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2007.

——. “Did Pirates Wear Eye Patches?” On the Under the Black Flag website at <http://undertheblackflag.com/?p=2904> or at <http://www.benersonlittle.com/bio.htm>.

——. “Eyewitness Images of Buccaneers and Their Vessels.” The Mariner’s Mirror, vol. 98, no. 3 (2012), 312–326.

——. The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths. New York: Skyhorse Publishing ,2016.

——. “El Mito Pirata.” Desperta Ferro, no. 17 (August 2015), 52-55.

——. The Sea Rover’s Practice: Pirate Tactics and Techniques 1630–1730. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005.

——. “Las Tácticas de los Piratas del Caribe.” Desperta Ferro, no. 17 (August 2015), 27-32.

Partenay. “Ainsy se fait voir le Petit Gouave au Sud-est et nord oist éloignée . . . ,” 1688. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Pyle, Howard. The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow. In “The Fate of a Treasure-Town” by Howard Pyle. Harper’s Monthly Magazine (December 1905).

Sabatini, Rafael. Captain Blood, His Odyssey. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1922.