Home » Posts tagged 'pirate raid'

Tag Archives: pirate raid

A Corsican Vendetta — Against the Pirates of the Caribbean!

January 23, 2023 8:51 am / 1 Comment on A Corsican Vendetta — Against the Pirates of the Caribbean!

Far too little-known are the Spanish corsarios of the Caribbean — the Spanish privateers and pirates who attacked the English, French, and Dutch in the service of Spain and of their own material interests! — yet the exploits of some deserve a book, an honest film documentary, or even a Hollywood film. I’ve already described the exploits of Italian corsario-in-Spanish-service Mateo Guarín, but those of the Corsican brothers Juan and Blas Miguel [It. Giovanni and Biagio Michele] are equally epic, and the final fatal exploit of Blas Miguel was in the service of a blood vendetta.

The tale begins with Juan Miguel. He arrived in Havana in late 1681 or early 1682 with a patente de corso — a privateering commission — dated 15 October 1681, from Juan de Arechaga, the governor of Yucatan, Mexico, to cruise along the coasts of Yucatan, Cozumel, and Tabasco for smugglers and pirates. Cuban waters were clearly beyond his commission’s authority, but Juan Miguel had a purpose in mind: to cruise new waters for greater plunder.

It’s entirely possible that Miguel had turned to el Corso in reprisal or revenge for attacks by pirates and consequent lost cargoes, just as some English merchant captains had turned to buccaneering after attacks by Spanish corsarios: he may be the Juan Miguel who, along with Captain Francisco de Ojeda, was plundered by English buccaneers in 1679 while sailing from Veracruz to Portobello. However, Juan Miguel was a common name, therefore this is speculation.

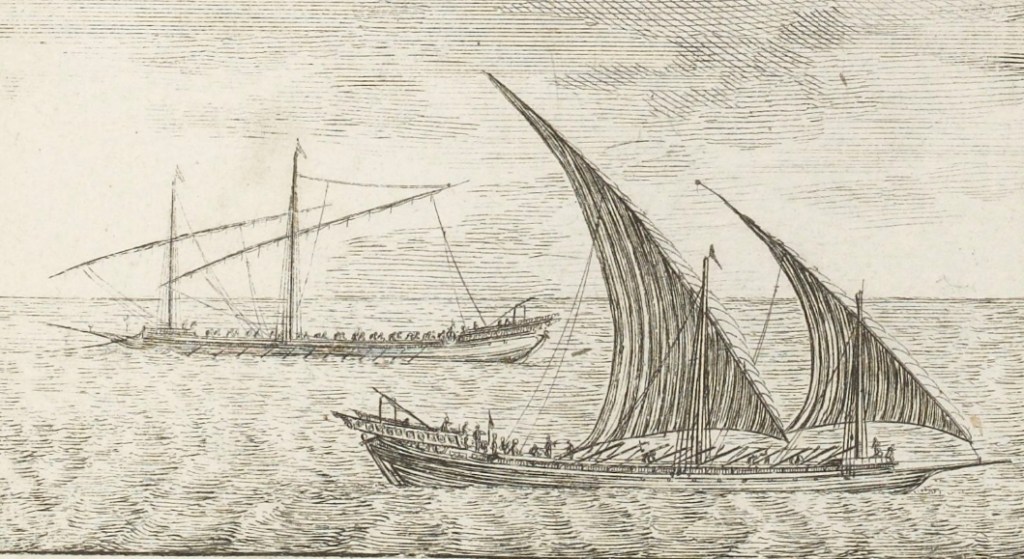

As a corsario Juan Miguel commanded an armed piragua, which often was nothing more than a very large dugout canoe, the largest of which could carry 125 men, with one or two masts and a short bowsprit, and armed with no more than two, or perhaps a few, wrought iron swivel guns known as patereroes (Sp. pedreros) on the gunwales. He was in the company of as many as two other corsario captains. One of them, Antonio Gómez, would soon command a small frigate captured in the bay of Santa Lucía, Cuba, and in 1683 would die in action against a smuggling sloop manned entirely or mostly so by buccaneers on hiatus from buccaneering, at Santiago de Trinidad, Cuba, a common location for smuggling and for fights between buccaneering smugglers and Spanish corsarios. The other captain was Juan Cañedo, although he may have associated with Miguel in Cuba instead.

Juan Miguel, with a new commission from Cuban authorities, soon put to sea again and captured smuggling canoes along the coasts of Honduras and Cuba. Along the latter coast he also captured an English bark smuggling logwood, and burned two other captured vessels because he lacked enough men for prize crews. Soon afterward, companion captain Juan Cañedo captured the English buccaneer John Spring (probably Captain Springer who gave his name to Springer’s Key and fought in the South Sea alongside Captain Bartholomew Sharp and others), among whose crimes was the decapitation of a priest in Guaurabo (Guayabon, modern Guayabo?), Cuba. Miguel’s next prize was a smuggling sloop, probably English, with 58 slaves and 46 boxes of sugar aboard.

Unfortunately, we know nothing more of Juan Miguel after this except that he died “in battle against the French from Petit Goave.” In other words, he was killed in action at the hands of French flibustiers. This has led some scholars to suggest that he was killed at the hands of Laurens de Graff, and from there they have leapt to the conclusion that he (as Miguel Curro) was captain of one of the several vessels of the Armada de Vizcaínos and was killed during a battle between the fleet and de Graff.

This Armada of Biscay, or informally, Basque Armada, referred to as La Armada de Nuestra Señora del Rosario by its admiral who would die of wounds received while attacking an English ship in an attempt to make off with its French prize, was a private pirate-hunting flotilla (three fragatas of thirty, thirteen, and twelve guns respectively, and one “barco de remos” or oared vessel) dispatched, largely unsuccessfully it turned out, to make up for perceived deficiencies in the Armada de Barlovento (Windward Fleet) of the Spanish navy. Given the privae armada’s apparent preference for trade over pirate hunting (pirate hunting has seldom been profitable), its failures are unsurprising.

However, neither Juan’s name nor his brother’s is listed among the those of the Armada captains, and it is highly unlikely that a local Mexican corsario commanded one of the ships of an armada financed and outfitted by the Compañía Guipuzcoana in Guipuzcoa (Gipuzkoa), Spain. Other scholars, looking more carefully at the evidence, consider it likely that Juan Miguel was killed during the sack of Campeche, Mexico in 1685 by buccaneers under the command of Laurens de Graff and Michel, sieur de Grammont, having returned to Yucatan after his cruises in Cuban waters.

In any case, Juan’s death triggered a vendetta: his brother Blas would avenge him by striking not at the homes and plantations of the buccaneer leaders, as Mateo Guarín had done, but at Petit Goave, the flibustier home port on French Hispaniola that had replaced Tortuga more than a decade prior. He would strike at the very heart of la flibuste and avenge not only his brother but all those who had died at the hands of the bloody French buccaneers.

Blas Miguel sought and was presented with a patente de corso “contralos enemigos piratas…y aquellos contrabentores” (against enemy pirates and any smugglers) dated February 26, 1687 by acting governor Don Andres de Munibe, “castellano del castillo del morro y Governador delas Armas,” in Havana. A copy of the commission still exists. Miguel also claimed to have had a commission from the “Viceroy.” However, no such commission exists in the archives, and there were only two Viceroys: New Spain and Peru. He probably meant that his commission from Munibe was issued under the aegis of the Viceroy.

Miguel’s privateering commission, its authority based on the Ordenza de Corso of 1674, which authorized Spanish privateering in the Americas, and on the Real Cédula of 1680 which authorized Cuban governors to take additional action to protect Cuban shores, also names Miguel’s vessel: a piragua called El Cachimbo, a Native American word meaning tobacco pipe. It may be the same Cachimbo commanded by Capitan Juan Nicolao who in late 1686 captured an English turtling sloop owned by Arthur Burham of Jamaica. In early 1689 Nicolao captured three more English turtling sloops. If the two vessels are the same, we assume that Miguel hired it, or it was purchased by his various investors.

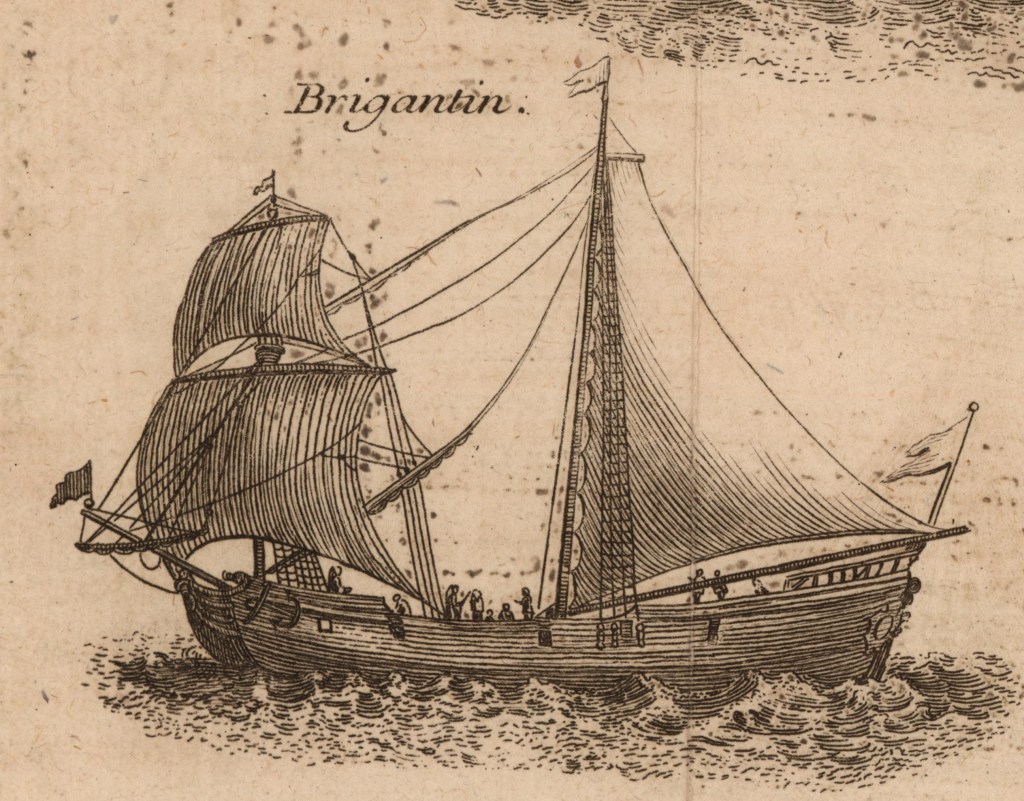

Given that French records describe the vessel both as a pirogue and as a demi-galère (half-galley), it is likely that was in fact the latter, known in Spanish as both a galera and a bergantin (a term that could mean two different vessels, here it is not to be confused with the French brigantin or English brig or brigantine). Although the piragua/pirogue/periager was specifically a large dugout canoe with oars and sails, the terms were also often used generally to indicate any large undecked (but for very small decks at the bow and stern) vessels that had both oars and sails, including half-galleys and barcos luengos (not to be confused with barques-longues — yes, the names of vessel types varied according to region, nationality, the passage of time, and confusion by lubbers who often used inaccurate terms). For more details on the half-galley, see the illustrations below and also the post on Mateo Guerín.

At what point Miguel chose Petit Goave as his target is unknown. Over several months he recruited eighty-three men (one source claims eighty-four), including himself, and added a second vessel as a consort, which would serve as a backup in case he lost the Cachimbo, as well as to ferry some of the corsarios and, hopefully, some of the plunder on the return voyage. Spanish records describe it as a balandra, which was a small coastal vessel, often a sloop (a single-masted, fore-and-aft-rigged vessel) but not necessarily one. French records describe it both as a bateau (boat) and as a brigantin, a small two-masted vessel square-rigged on the foremast and fore-and-aft-rigged on the main. Given that it was described as both, it was probably a very small brigantin. Mateo Guerín, that famous Italian corsario in Cuban service, loaned Blas Miguel the money for the brigantin.

We know the names of eleven of his officers and crew. Blas Miguel (in French records, variously Bras Miguel, Brasse Miqael, Blas Michel, Blas Michelet), about forty years old, a native of Corsica, commanded the expedition, and said he came to “pillage, steal, and burn the Quarter [of Petit Goave].” Santos de Acosta was his second-in-command. Lieutenant Diego Ruiz and Soriano Pardo, the latter from Santiago, were also officers of unspecified duties. Teniente de Guerra — “Lieutenant of War,” probably a militia officer — Juan Quijano was also aboard, likewise of unspecified duty.

Pasqual Juan (in French records Pasqual Ouan — phonetic French for Juan — therefore possibly Juan Pasqual; also Pasqual Onan, Pascoualles Onan [likely transcription errors], Pascoualle Ouan, Pascual Ouan),* a Native American from Campeche, Mexico, about twenty years old, said he came to “destroy and pillage [Petit Goave] entirely, to kill and massacre all the whites [pour tuer et massacrer tous les blancs], and take away the women.” He was considered by the French to be one of the chiefs (Chefs) and principal authors of the expedition, although this was probably untrue. More on this later.

Louis Martín, twenty years old, a native of Santiago de Cuba, said he came to “search for life [chercher la vie — to make a living?] and had heard the Oidor [a judge of the Audiencia] and others say to give no quarter to anyone and to plunder the Quarter entirely.” Juan de Piqueras (“Piqueray” in French records), a mulatto from Cartagena de Indias, thirty-six years old, came for the same reason as his companions.

Juan Antonio Sanete, a mulatto, thirty-four years old, likewise a native of Cartagena de Indias, said he came ir corsario (“pour fair la course,” to go privateering). Juan Eusebe Servan, twenty-nine years old, a native of Havana who lived at Trinidad de Cuba, likewise came for privateering. Juan Miguel, (no known relation to Blas Miguel), a pardo (typically taken to mean a person in Spanish America of mixed white, black, and Native American ancestry), was also a member of the crew.

According to French records, the crew was multi-national, in equal parts “whites, mulattoes, Native Americans, and Blacks.” The Native Americans among the crew — “Indes” in French records — were likely both Native Americans and mestizos. Spanish corsario crews in the Americas are typically described as broadly of mixed race and ethnicity in accounts of the period.

Additionally, it was common to have a few Italians, Corsicans, and Sardinians among the crew, along with a few “Levanters,” also known as “Greeks,” as well. Levanters hailed from the Eastern Mediterranean, the Greek Islands in particular. Blas Miguel is described in his commission not only as Corsican, but also as a pardo, perhaps due to mixed Italian and North African ancestry. English accounts of the era typically note this various multi-ethic composition of Spanish privateer, pirate, and guarda-costa crews (often such crews were all three), in blatantly racist language.

In June 1687 Blas Miguel set sail from Casildo, two leagues east of Trinidad de Cuba. At the Río Zaza they came across two registro ships, one from Cartagena de Indias and one from Puerto Bello, and may have recruited some seamen from them, including Piqueras and Sanete. At Santiago de Cuba the expedition remained for twenty days recruiting, bringing the number to a final eighty-three. Here part of the crew had a change of heart and deserted ashore, including Luis Martín. But the local judge ordered them all to return aboard, or face arrest and two hundred “strokes of the cane.” The corsarios put to sea, sailed to Baracoa, and remained there a month, making final preparations.

In early August the punitive and plundering expedition set sail. En route near Petit Goave they captured two canoes with four persons aboard each, one of which held a Frenchman named Saint-Anthoine from nearby Léogâne whom they forced to serve as a guide. No flibustier vessels were in port as the Spanish corsarios came near Petit Goave on August 10, 1687. Blas Miguel may have had advance intelligence, or knew the general patterns of the buccaneers of Petit Goave, or sent a canoe ahead in advance, or was advised of this by Saint Anthoine. Or even by all of these methods.

Leaving the brigantin to stand off from shore, Blas Miguel, with sixty men divided into four companies to go ashore, and a small sailing crew to remain aboard, approached Petit Goave at dawn. He had originally intended to land at midnight, but Saint-Anthoine cleverly dissuaded him, by telling Miguel they could capture the Quarter “without the loss of a hair” at dawn, but at midnight would be in danger of killing each other in the dark. Blas Miguel agreed.

At the fortalice that served more as a corps du garde than as a harbor defense at Petit Goave, only three or four men were on duty. Their officer, a veteran former buccaneer captain named Vigneron who had commanded the four-gun barque Louise and had sailed with Laurens de Graff, Jean Rose, La Garde, and other famous flibustiers. As the Cachimbo began putting men ashore, Vigneron challenged it. “D’ou estoit le canot? [“Whence the canoe?” aka “Where do you come from?]” he shouted.

Saint-Anthoine replied, “Saint Anthoine qui vient de Léogane. [Saint Anthony who comes from Léogane.” Again Vigneron demanded, “D’ou estoit le canot?” This time Saint Anthoine responded aggressively and repeatedly: “Saint-Anthoine aux armes! [Saint Anthony, to arms!]” We imagine the prisoner-guide was immediately killed by his captors for warning the French.

Vigneron, and probably his men too, fled the fort, for they were too few to hold it, and ran through the town shouting, “Aux armes!” The four corsario companies surged ashore. Two of them, including Blas Miguel, occupied the fort while the other two, soon guided by former Spanish slaves and mulattas captured from Spanish territory, headed east toward the several rich Maisons. The attackers knew that any French armed assistance could come only from Acul across the bay; Léogane was two days away.

The exact armament of the corsarios is unknown. Only two weapons are mentioned incidentally in French records: the machete and bayonet. However, the primary weapon would have been a long firearm. The standard military weapons of Spanish infantry, militia included, at the time, were the mosquete and arcabus, both matchlocks, which were not the ideal firearms for raids. Even so, it is likely that some raiders were armed with the arcabus, which was smaller in caliber than the mosquete and did not require a rest.

Other raiders were probably armed with the escopeta, a light flintlock (usually a Miquelet lock) musket commonly used for hunting and a much better long arm for raiding. (Note: the escopeta was not a “shotgun,” and therefore, by flawed reasoning, a blunderbuss, pirate reenactors and Hollywood script writers unreasonably enamored with the blunderbuss notwithstanding. The definition of the escopeta as a shotgun came later, as cartridge arms with rifling were introduced, and smoothbore muzzleloaders began to be used as shotguns, a purpose to which they were well-suited.) Some corsarios were likely armed with carabinas (carbines): short-barreled flintlock muskets used by cavalry and dragoons, including those of Spanish regulars and militia in the Americas.

Some corsarios may have also been armed with pistols; the 1674 Ordenza de Corso permitted this, although likely some would have been armed with them without the legal authorization. All or nearly all would have been armed with a machete or cutlass (alfanje in Spanish, also often sable). The term machete is noted twice in French records, and may have meant machete, a common tool and weapon, or more generally to indicate a short cutting sword, whether cutlass or machete.

Corsarios who considered themselves hidalgos (gentlemen), likely many of them, may have been armed with cup-hilt rapiers and parrying daggers instead of cutlasses, as in the illustration at the head of this post. At least one bayonet is noted, probably fixed in a musket barrel. It may have been a hunting bayonet rather than the military bayonet now becoming quite common, and may have been carried by many corsarios. Most attackers were probably armed with some form of knife: a bayonet, dagger, or other fixed blade, or a large folding knife of a form common to Spaniards.

The French defenders were of two sorts: flibustiers and former flibustiers who would have been armed with the famous long-barreled fusil boucanier, a pistol or two, and a cutlass (Fr. coutelas, sabre), and habitans in the militia who were by this time typically armed with the fusil boucanier and a bayonet or cutlass, or with both edged weapons. Some, officers particularly, may have been armed with pistols as well.

As the corsarios attacked, one company assaulted the home of Procureur Général du Conseil Supérieur [Président in some accounts] et Capitaine de Milice du Quartier du Petit Goave, Jean Drageon-Dupuy (also Dupuis), to the east. The militia captain, just awakened, attempted to fire on four or five attackers, we imagine with a fusil boucanier — loaded with a ball and seven or eight swan shot, as buccaneers often did, it was a superior close quarters firearm (far superior, for example, to the blunderbuss). But his weapon missed fire, and one of his attackers cut off his head with a machete.

When the attackers came upon his pregnant wife, she pleaded for her husband’s life, then, seeing him dead, she pleaded for good quarter for herself. And for a short time, quarter was granted to her while the corsarios pillaged. In the house they murdered a young boy with twenty-eight cutlass blows, then returned and bayoneted Drageon-Dupuy’s wife, killing her and her unborn child in spite of the grant of quarter.

Meanwhile, an officer of the sieur Novays arrived on scene, and with his men killed three corsarios of a dozen or so who had ranged through the streets and had killed a resident. The officer and his men also soon put to flight all those who had attacked the house; the corsarios fled with only their arms.

Commanded by Blas Miguel’s lieutenant — probably Santos de Acosta — the two companies headed toward two or three other rich Maisons, plundering them of valuables, arms, and powder, and breaking their furniture and furnishings. But within an hour to an hour and a half, depending on the witness’s account, a French militia force of two dozen or so, both cavalry and infantry, arrived and counter-attacked, killing Miguel’s lieutenant and two other corsarios, and forced the rest to retreat under fire to the fort.

Each side fired furiously at the other; three French militiamen were killed, and four more, including an officer, were wounded. The French militia also fired on the half-galley and brigantin, forcing them to stand off from near the shore. Meanwhile, five corsarios, with what plunder they might have carried in their pockets and nine or ten Spanish mulatta women, who may have been free or slaves when originally captured by the French, slipped into the corsario boat and escaped to the half-galley.

During the firefight, the French wounded many corsarios and killed seventeen. (The number is probably the total killed during entire day. If this number is correct, there were sixty-four corsarios ashore, suggesting companies of fifteen plus one officer each.)

A former flibustier named Brasse slipped into the water during the battle and with only a machete or cutlass captured the half-galley’s canoe and the prisoner in it (or took its coxswain prisoner; the account is not entirely clear). Soon, the corsarios realized they had no way out. Blas Miguel sent a “femme de mauvaise vie” — a “fallen woman,” a prostitute — with a letter stating that the corsarios would give back their plunder if the French permitted them to depart.

Instead, the French redoubled their fire and soon Blas Miguel and his men surrendered. The official record states that forty-seven surrendered and were imprisoned in “cachots” — dungeons — but the term is probably figurative, indicating warehouses and other buildings quickly converted for use as jails.

The following day a Conseil de Guerre (a Council of War) composed of fourteen militia officers was convened. The council interrogated six of the corsario prisoners, using a militia cornet of horse, the sieur Jean Duquesnot, to translate. Blas Miguel claimed to have had two commissions but had left them in his piragua. We know he had one patente de corso. It was common practice to carry a copy ashore, but he had not. Having no commission at hand, he was considered to be a pirate.

Justice was swift. Forty-two corsarios, or “forbans” — pirates — as the French referred to them, were sentenced to be “hanged and strangled until death” the following day for “plundering, burning houses, and raping and massacring even women.”

Blas Miguel and Pasqual Juan were sentenced to be broken on the wheel the day after, for their being the chiefs and principal authors of the raid. Two, a young boy and a Black slave, were spared because they had been forced aboard the punitive plundering expedition. This makes forty-six, not forty-seven; we may assume one corsario had died of his wounds in the interim.

The sentencing leaves us with an obvious question, at least once the evidence is examined closely. Why was Pasqual Juan sentenced to be broken on the wheel? French records state that this was because he was one of the “chiefs” and “principal authors” of the raid. But was he? Spanish records do not record his name among those of the officers. He was a very young man, a Native American, and a native of Campeche, Mexico, a city that had been brutally sacked by French buccaneers two years before.

And he was also an angry young man who said he came, among other reasons, to kill and massacre all the whites in Petit Goave. He was the only interrogated prisoner to claim this. Very likely he was neither an officer nor an author of the raid. Instead, he was almost certainly broken on the wheel for his testimony that he came to kill white people. To the colonial mind, any form of rebellion against the European hierarchy must be violently, horribly suppressed.

Such racial animosity toward white foreigners is unsurprising. As buccaneers they had not only raided, plundered, tortured, raped, and burned Spanish towns, but also often captured free men, women, and children of color and sold them as slaves. And alongside this lay the enormity of the commercial enslavement of Africans, and often of Native Americans as well, throughout the Americas.

Slavery touched everything. But no faction or people in the Americas had entirely clean hands, although it is surely accurate to say that European hands were the dirtiest. Even so, it can sometimes be difficult to draw a distinct line between European nations in the Americas and the Native American and African cultures they had begun to blend with. Even during the Colonial Era the Americas would never be a mirror-image of Europe.

The seeds of the early nineteenth century Caribbean and Latin American Wars of Independence were already sown, although Spain would manage to hold onto Cuba until the Spanish American War with the United States.

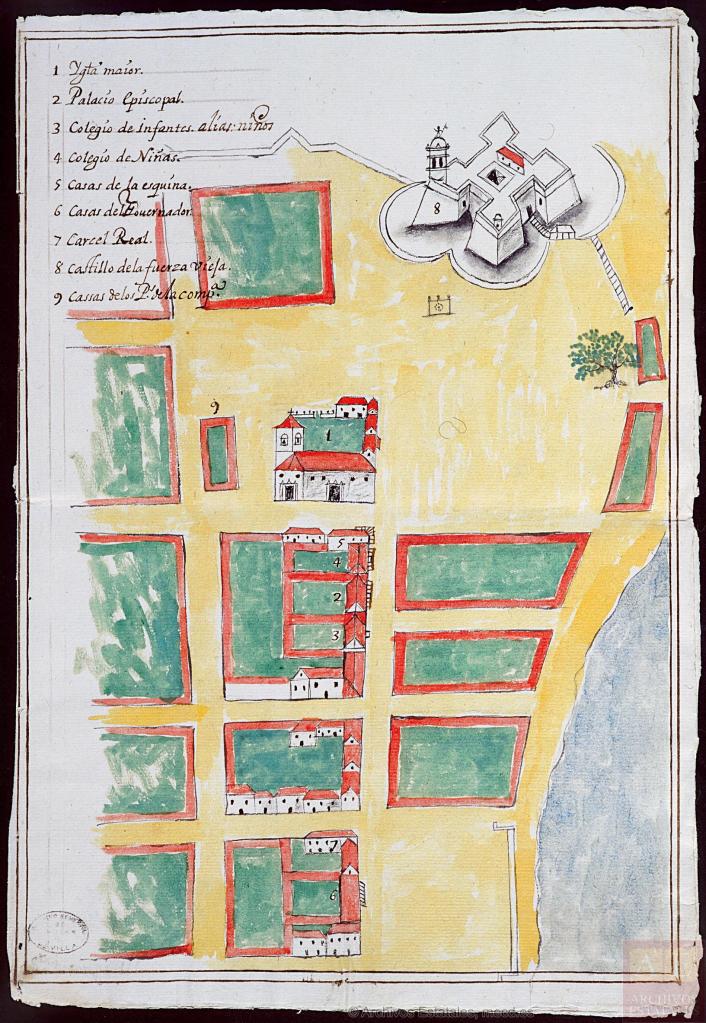

On August 11, 1687, forty-two corsarios were hanged. Maps of Petit Goave show only a single small gallows at the shore. If it alone were used the hangings would have taken all day. Perhaps other gallows were erected, or perhaps Governor Hender Molesworth was correct when he wrote that “About a hundred Spaniards landed lately at Petit Guavos in the night, and, the place being thinly inhabited, made themselves masters of the castle, but were all put to the sword by the French, except some who were reserved to be hanged, and the captain, whom they racked to death for having no commission.” Perhaps the sentence of death by hanging was figurative and the French simply put some to death by firearm and sword and hanged the rest.

On the following day, August 12, 1687, Blas Miguel and Pasqual Juan were broken alive on the wheel. Father Jean-Baptiste Labat, that eyewitness chronicler of all things Caribbean in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, left us with a description of the horrible punishment, often known as rouer in French. It is truly a death by torture: the executioner used a hammer, heavy wooden staff, or perhaps even an “epée dans un bâton” or “stick-sword” (see Louis de Gaya, 1678) to break the bones of the condemned who was bound with his arms and legs outstretched, often to a wheel although this was not mandatory. In the West Indies a cross was sometimes used, for example. In either case the wheel or cross was typically mounted on a platform for better view and ease of execution of sentence.

Labat described the condemned mounting the scaffold, kneeling, praying, then undressing and stretching out upon a cross. With a hammer the executioner then broke each of the long bones in the condemned’s arms and legs several times. If the condemned was fortunate, a priest might cover his face with a handkerchief during the excruciating process. The executioner ended the agony — if the condemned were not already dead from the trauma — by strangling him with a rope, first permitting a priest to ask the condemned for, and perhaps receive, a last act of contrition. We imagine that strangling was not always used, and a final blow was made instead.

Thus ended the vendetta of Blas Miguel to avenge his brother’s death at the hands of the French at Petit Goave. At least Laurens de Graff was not present to laugh in Blas Miguel’s face as he went to die.

But soon enough the Spanish would take a double measure of revenge, as would the soul of Blas Miguel, a few years later during King William’s War. In 1690 a force of 2,600 Spaniards attacked Saint-Domingue. At the plain of Limonade they faced the French under Governor Jean-Paul Tarin de Cussy. At first, the powerful Spanish force withered under accurate fire of French buccaneers who had demanded to fight on the plain, but a sudden charge by lanceros — typically men of color afoot, armed with lances — who had lain hidden nearby broke the French line. De Cussy and his lieutenant, Franquenay, stood their ground and died upon it. The invading Spanish force plundered the French capital Cap François, murdered all the men they found, raped women, and carried away women, children, and slaves, in part in retribution for decades of bloody, brutal buccaneer raids.

In 1695, during a during a joint English-Spanish raid, a double measure of revenge against Laurens de Graff was had: the former buccaneer was roundly criticized and shamed, whether deservedly or not, for his lackluster defense against and retreat from the Spanish attack, so much so that he was called to France to face charges. Worse, at least we hope it was to him, his wife Anne and his children were captured. But once more Petit Goave was not attacked, and de Graff was no fool and so ignored the royal command.

A measure of revenge against Petit Goave did come in 1697 at the hands of the English Navy. Arriving after chasing and losing the quasi-naval privateering fleet of the baron de Pointis which had just sacked Cartagena de Indias, Rear Admiral Mees was tasked by Admiral Nevill to destroy Petit Goave, now a nest of lawful flibustier privateers, many of whom had just returned from Cartagena de Indias. He organized a detachment of 897 men, placing almost two thirds of them in boats. Launching some 16 or 17 leagues from Petit Goave, Mees led four hundred men ashore at 3:30 AM one mile east of the town.

They quickly captured the fort, which had only one cannon mounted, and six of the guard, the rest escaping. Quickly the English captured the remaining small nearby batteries of cannon while most of the inhabitants fled. Those who did not flee were captured and placed in the fort under guard. Soon, though, English sailors started to do what they were well-known to do ashore: get drunk and start plundering, for many houses were rich with plunder and shops rich with goods. After an hour or two, Mees was forced to set fire to the town, fearing his men in their drunken state might not stand against a counter-attack.

As the town burned, and houses exploded due to the powder stored within them, the French were able to make only small counter-attacks from hedges and trenches, many armed with swivel guns. The English captured two French colors, killed an Ensign and another officer, wounded an officer on horseback, and killed and wounded an unknown number more while taking casualties of thirty killed and thirty more wounded of their own. One English volunteer officer with eight men forced thirty French to retreat from a trench, and killed their officer. In the end, the attack amounted to little more than a mere punitive raid.

Afterward, the spirit of Blas Miguel must surely have wondered what its former incarnation might have done with four hundred veteran professional fighting men instead of a mere eighty-three various volunteers.

The description of the raid has been drawn largely from the following:

El Corso en Cuba Siglo XVII by César García del Pino (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2001);

La Defensa de la Isla de Cuba en la Segunda Mitad del Siglo XVII by Francisco Castillo Meléndez (Seville: Diputación Provincial, Sevilla, 1986);

“Audition des Espanols qui sont mis a terre au Petit Goave prisonniers au fort de dit lieu,” ANOM, C9/1/1;

“Lettre et mémoire de Cussy au marquis de Seignelay, Port-Paix, 27 August 1687,” ANOM/C9A/1;

“Jugement du Conseil de Guerre, Petit-Goave, 11 August 1687,” reprinted in Loix et constitutions des colonies françoises de l’Amérique sous le Vent by Louis-Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry;

“Lieutenant Governor Molesworth to William Blathwayt,” August 8, 1685 (Old Style), Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, America and West Indies, 1685-1688.

The description of the English raid on Petit Goave has been drawn from “An account of the Burning of Petit Guavas the 28th June 1694…,” published in The Sergison Papers, 1950.

* Curiously, the French translator, or the transcriptionist/clerk, wrote “Jean” for “Juan” in most cases, did not do so in the case of Pasqual Juan, but wrote “Ouan” instead. Did Pasqual Juan pronounce his name differently? Was Spanish perhaps a second language? Or was Ouan in fact an indigenous name? If so, I have been unable to trace it.

Copyright Benerson Little 2023-2024. First posted on June 14, 2023. Last updated March 25, 2024.