Home » Posts tagged 'Pirate Tropes'

Tag Archives: Pirate Tropes

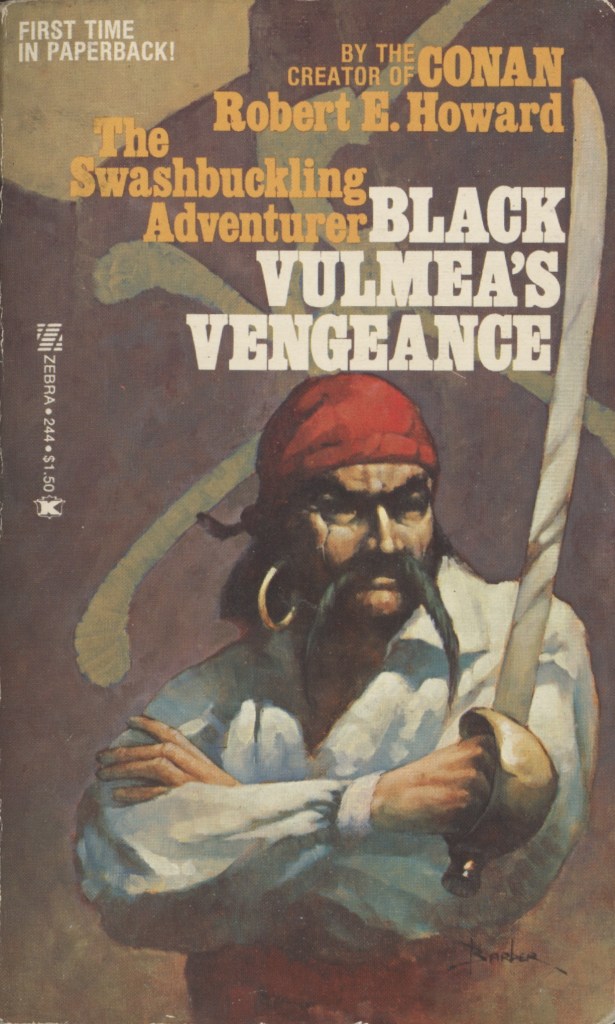

Pirate Pulp Fiction Paperback Cover Art!

For fun!

I’m not going to pretend to write a pretentious analysis of pop cover art and imagined social implications, nor any other nonsense. I’m neither an art historian nor inclined to see things that aren’t really there. Suffice it to say that these covers are intended to be eye-catching, often titillating, and always bordering on near-lurid, entirely to lure potential readers to buy the book. The accompanying cover copy, the blurb especially, is almost as over the top as the art. This isn’t a criticism, for similar art and copy is often found on the covers of far more notable works.

As for the text inside? Suffice it to say that it’s not comparable, in spite of the cover copy claims, to that of Rafael Sabatini or any other notable writer of romantic adventure. Pirate pulps are almost always extremely light on literary substance and historical accuracy, and quite heavy on cliché. Trope writing in other words. Sheer fantasy in the sense of “never happened.” Pure swashbuckling pirate genre in the form of the twentieth century version of dime novels. Enjoy!

Copyright Benerson Little, 2021 – 2022. First posted May 20, 2021. Last updated May 9, 2023.

The Women in Red: The Evolution of a Pirate Trope

With news that Disney is planning a new standalone pirate film starring a female pirate, it’s time review what has become a pirate trope: the woman in red, specifically, or at least often, a redhead. Why this trope in regard to a new Disney film? Because speculation has it that the film will be tied to Redd the Pirate above.

UPDATE: According to Margot Robbie in the press on November 14, 2022, Disney has killed the project, although rumors periodically surface that Disney continues to look at continuing the franchise, including a film with a female protagonist. A pity indeed that the rumored Robbie film was cancelled, it might’ve been quite the film. Certainly the genre needs a new female-led pirate film hearkening back to the Golden Age of Piracy and Pirate Film. There have been only a few made. Shout-out to The Pirates (2014), a Korean comedy-drama about Korean pirates, with strong overtones of the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, starring Son Ye-jin. (And please let it not be about Anne Bonny! See below…)

In the meantime while waiting for a new pirate film with a female lead, we’ll take a quick look at some of the myths and realities of female pirates during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy in the Americas from roughly 1655 to 1730.

The obvious apparent origin of the woman in red (a “scarlet woman”?), at least in terms of pirate fiction and film, is the Redhead in line in the bride auction–“Take a Wench for a Bride”–in the original version of the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean attraction in which drunken pirates shouted, “We wants the redhead!” Forced marriage, in other words, and all of its associated crimes.

Notably, text on the back of the publicity still describes the scene as an auction: “Gold-hungry pirate captain puts the town’s fair maidens–and the ones not so fair–on the auction block for his rowdy crewmen.” Thankfully, things have somewhat changed since then, tongue-in-cheek humor or not.

The Disney auction scene was doubtless inspired by scenes in The Black Swan (1942), Anne of the Indies (1951), and, in particular, Against All Flags (1952), in which captured women are portrayed as captives to be sold or given away as plunder. Both Anne of the Indies and Against All Flags have auction scenes of female captives, and the latter has an auctioneer with whip-in-hand as in the Disney attraction.

When it first opened in 1967, the Disney attraction was intended as–and in fact was–a tongue-in-cheek, lighthearted, swashbuckling film-based version of buccaneers sacking a hapless Spanish town in the Caribbean. Marketing text associated with early publicity stills noted that the ride was a “thoroughly realistic re-creation of buccaneer days.”

To enjoy the ride–which I did and still do–requires viewing it as a fantasy rather than a depiction of reality, for the reality of buccaneer attacks in the seventeenth century was anything but romantic to the victims: torture, rape, murder, and the enslavement of free men, women, and children were common. Documentary evidence of what today would likely be defined as resulting PTSD, among both victim and perpetrator, exists.

Like most of our fictional and cinematic adventure, we tend to sanitize or ignore facts in order to help create a fantasy more amenable to entertainment. Humans have done this for millennia. And there’s often nothing wrong with this unless we confuse the fantasy with the reality, which unfortunately happens all too often.

Today, the ride has been modified somewhat to both fit with the Disney pirate films, which are only loosely inspired by the attraction, and to bring the attraction up-to-date with current social mores. The latter changes have generally been a good thing, I think, even if the changes are not historical. The attraction is a swashbuckling fantasy, after all, not an accurate “Audio-Animatronic” documentary. I’m much less enamored of the changes in keeping with the film franchise.

The most significant of the changing mores alterations to the attraction was the conversion of the pirates-chasing-women scene into one of pirates-chasing-food, and the conversion in 2018 of the bride auction scene into one of conquered residents bearing possessions, perhaps as ransom, and of the famous red-dressed redhead showing a leg into a red-dressed redheaded female pirate standing guard (and still, after a fashion, showing a leg).

Personally, I much prefer the new scene and new redhead, ancient passing pre-adolescent fantasies notwithstanding.

In general, as in the original trope-setting (and great fun to watch) pirate swashbuckler, The Black Pirate (1926), leading women in pirate films are usually depicted as the “tavern wench” or “exotic wench,” or other saucy secondary love interest; or the “swooning heroine;” or the “pirate woman.”

The “pirate woman” is usually by far the most interesting, although too often she, Hollywood-style, gives up piracy at the end of the film in exchange for true love. Or she dies in battle, her true love unrequited, her true love interest running off with the “good girl”–often the swooning heroine. At least Cutthroat Island with Geena Davis avoided this trope.

Sometimes the tropes are combined: Elizabeth Swann in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl goes from a nod at the literally swooning–via an over-tightened corset (“stays” to be correct)–heroine to pirate woman.

She also wears a red dress in the first film of the series, in scenes which combine multiple tropes: woman in peril, woman tied-up, woman with (airbrushed via CGI, reportedly) cleavage. The dress is a likely homage to the Disney attraction. A red dress also shows up on Scarlett, a tavern wench aka prostitute.

The red dress shows up in other pirate films as well, and as apparent copies or homages in Halloween costumes and video games.

Geena Davis stars in Cutthroat Island (1995, Carolco), and in one scene swashbuckles her way tolerably well in a red dress borrowed from a prostitute. The dress is clearly a nod, perhaps more than a bit humorous, at the Disney ride. In fact, Cutthroat Island often seems like one long string of pirate tropes, homages, and stolen scenes. Great soundtrack, though, and Davis does well as a pirate captain.

Now is a good time to briefly point out the reality of women pirates during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy 1655 to 1730. Strictly speaking, we know of only two who can be truly said to be pirates of the Caribbean: Anne Bonny and Mary Read, the former of whom gets all the cinematic glory while the latter, if what Charles Johnson wrote about her is true even in part, was the real swashbuckling bad-ass of the twain.

If Johnson’s early eighteenth century account is true, Read had been thrice a soldier in disguise, then a pirate, and even a privateer, in disguise, and reportedly fought at least one duel against a male crew member. Of course, this may be entirely an invention of the author, and his account of Read’s army service may have been inspired by the real life of female soldier-in-disguise Christian Davies. Although a fictionalized account of her life was not published until 1739, her story was known at the time Johnson’s pirate book was written.

Whether a true tale or not, it’s not Read’s warrior-woman story that ends up in fiction and film, but that of redheaded Anne Bonny–or at least she’s assumed to be redheaded because she was Irish and reportedly had a hot temper. Bonny gets all the glory, even though she may have been merely the girlfriend along for a joyride with her bad boy pirate boyfriend. Or not. We simply don’t know enough about her or Mary Read. Johnson may have invented the past histories of both to “sex up” his book for sales potential. But it’s also entirely possible that both were as bold as Charles Johnson described them.

Bonny, though gets all the attention, thanks largely to her relationship with “Calico” Jack Rackham. Writers are often lazy, and it’s easier to combine Read’s martial prowess with Bonny’s reported temperament and relationship with Rackham. However, not all writers who fictionalize the female pirate pair are as lazy. Some, including Erica Jong, have balanced their accounts of the two women.

But it’s Read, in my opinion, who deserves a movie.

Perhaps Anne Bonny, the assumed redhead, has also given us the redheaded part of the redhead in the red dress trope.

There are no other known women pirates of the Golden Age but for two who were technically pirates under the law, each having participated in utterly inept attempts at petty piracy, one of them comically so. Notably, two of the most commonly cited women pirates of the era were not pirates at all (please please please ignore Wikipedia!): Jacquotte de la Haye is entirely fictional, a creation entirely of author Leon Treich (Les Gentilshomes de la Flibuste, 1944, a factual-fictional account of buccaneers and some pirates written for a juvenile audience), and Anne Dieu-le-Veult, a wealthy widow, married the famous Laurens de Graff after his buccaneering days. She was never a member of his crew, nor is there any evidence that she was a member of any other crews. Treich is also responsible for exaggerating myths about Dieu-le-veult to an even greater degree, and even imaging deeds that never happened (including the utter nonsense that de Graff died in battle at her side).

More detail on Rackham, Bonny, and Read can be found here.

Likely though, there were real buccaneer and pirate women we’ll never know about because they remained in disguise. The common sexism of the day prevented women from becoming obvious members of a pirate crew. In fact, it’s probable that Anne Bonny and Mary Read (in Read’s case, after she revealed her sex) were part of John “Calico Jack” Rackham’s crew only because it was very small, no more than a dozen or so aboard a twelve-ton (that’s very small) sloop.

Pirates by majority vote could override their captains anytime but in action, and a larger crew would doubtless never have permitted women aboard as equals. In general, women were forbidden among early eighteenth century pirates except as prisoners, and even then pirates preferred to keep them away out of fear of indiscipline among the crew.

Red dresses pop up in other pirate or pirate-associated films as well, but it’s hard to tell if they qualify as tropes. Red is a popular dress color, after all: it stands out well and is often associated with temperament and sexual license, accurate or not.

In 1952’s Blackbeard the Pirate starring Robert Newton, heroine and damsel-in-distress Linda Darnell, in the scene most often used for advertising posters and lobby cards, is often depicted in red rather than the actual dark blue in the film. Clearly, there is marketing value in placing a woman in red clothing. In some cases she is even depicted as redheaded rather than as raven-haired as in the film and in life.

Honorable mention must go to pirate queen Black Sheba in George MacDonald Fraser’s comic novel The Pyrates (1984): “she donned her scarlet silk breeches and shirt, buckled her dimanté rapier at her hip, drew on her long Gucci boots, exclaimed at the state of her coiffure, clapped on her plumed picture hat, dapped a touch of Arpège behind her ear, and then spent ten minutes selecting one long earring and applying her lipstick.” She is by far the fiercest and sexiest of all the pirates in the book–a pirate queen as only a novelist or Hollywood could create.

A phrase in the novel, “dark and sinister woman…,” gives away part of her inspiration: she’s at least to some degree a female Captain Hook, the wordplay on the color of her skin notwithstanding. (“Proud and insolent youth,” said Hook, “prepare to meet thy doom.” “Dark and sinister man,” Peter answered, “have at thee.”) Even so, Fraser in the afterword describes the pirate queen as “a Dahomey Amazon with echoes of Lola Montez, Queen Ranavalona, and a pantomime principal boy.” Note also that the character of Bilbo–named for the slang term for sword and not for the Hobbit–is according to the author, “Basil Rathbone playing a raffish Captain Hook.”

Also, at one point Fraser dresses one of the two more “traditional” heroines, Lady Vanity, in a maroon velvet dress, almost certainly, given his numerous other homages to piratical Hollywood and fictional tropes, in honor of classic pirate film heroines in red, and quite possibly of Disney’s woman in red as well. The dust jacket below shows another of the heroines, Dona Meliflua, also in red.

Nonetheless, Blackbeard the Pirate and other films (and novels!) notwithstanding, there is a possible ultimate origin for the redhead in red dress trope prior to the Disney attraction–in fact, its inspiration perhaps, or at least part of it.

In 1952 Columbia Pictures released The Golden Hawk, a pirate film, albeit one technically about French and Spanish privateers in the Caribbean in the late seventeenth century.

The male lead was Sterling Hayden playing Captain Kit Gerardo. His acting appears a bit wooden by Hollywood pirate captain standards until you read his biography: a true tall ship captain in his youth, later a Silver Star recipient and US Marine Corps officer assigned to the OSS (the precursor to the CIA covert operations department) behind enemy lines in World War Two. In other words, he was playing himself as a privateer captain. Even so, Variety magazine wrote that Hayden was “out of his element as the gallant French privateer…” Hollywood goes for (melo)drama, but most real captains are far more quiet and self-assured. They have to be. But I digress.

The female lead was red-haired Rhonda Fleming, one of the “queens of technicolor,” the most famous of whom was Maureen O’Hara who starred in several swashbucklers and whom some critics suggested would have been better in the role–and better for its box office.

Fleming’s character in the film is “fiery,” to be expected of the popular genre, including the Frank Yerby novel on which the film was based. In one scene–SPOILER ALERT!–she shoots Kit Gerardo when he makes “romantic overtures” to her, then leaps out a stern window and swims ashore. No swooning heroine she, thankfully, nor one to put up with sexual harassment or worse.

In a few scenes, Fleming, whose character’s real name is Lady Jane Golfin, wears a luxurious green dress. But in most lobby cards, tinted publicity stills, and movie posters, it’s red.

More importantly, Rhonda Fleming plays a buccaneer, Captain Rouge (that is, Captain Red)–she was also a pirate!

We may have simultaneously moved forward while also coming full circle. 🙂

Postscript July 22, 2020: This bears repeating: Please, please, please do not use the Wikipedia entry on women pirates for research! At least not if you’re looking for facts. 🙂 Wikipedia has a number of flaws in many of its articles on piracy (and in many other areas as well), including factual errors, incomplete information, inadequate or incorrect sources, trolling (intentional factual misrepresentation to trigger a reaction or otherwise for fun), severe ideological slants leading to inaccuracy (i.e. deliberate “scholarly” misrepresentation, often in support of social or political ideologies attributed to pirates, yet run counter to historical fact), and fairly constant regressive, incorrect changes to accurate information. Some of the articles are occasionally accurate, but all too soon are revised inaccurately again.

Copyright Benerson Little 2020-2023. First posted July 8, 2020. Last updated July 8, 2023.