Home » Posts tagged 'Pirates of the Caribbean'

Tag Archives: Pirates of the Caribbean

The Fanciful, Mythical “Calico Jack Rackham” Pirate Flag

This is not a post I’d ever intended to write, believing–clearly foolishly–that publishing a book on pirate myths would once and for all send the the myth of Rackham’s pretended “skull and crossed swords” flag to perdition where it belongs. Or mostly so. How naive! It’s not just hope that springs eternal–so does myth flying in the face of contrary fact.

Although it’s well-documented that the “Rackham” flag–quite probably the most-depicted pirate flag in film–is a fanciful 20th century invention, Wikipedia via trolls and the ignorant continues to spew nonsense regarding both Rackham and this flag, the latest of which I learned, via a historical forum on Facebook, is that the two crossed swords might represent Anne Bonny & Mary Read. (For the record, all either of them did with a sword–quite possibly a machete, in fact, based on a witness statement–as pirates as far as we know is wave them at frightened merchant seamen who had already surrendered.) I’ll get to the ridiculous notion that the swords represent the women pirates in a moment.

Trying to correct Wikipedia is like playing Whack-a-Mole; it’s never-ending. Wikipedia is a prime resource for the lazy and the gullible, and trolls and others attempting to distort facts are well-aware of this. It’s one of the best places today to replace fact with nonsense, or worse. Don’t get me wrong: there are excellent articles on Wikipedia, including some on pirates and piracy. But to the uninitiated it can be hard to tell the difference between these and those that are little more than nonsense or outright propaganda. And even the best ones are often soon rewritten–and their important facts often disappear with the revision.

A few facts about Rackham & Co. before I describe the 20th century origin of the flag:

There is no record of any pirate flag John “Calico Jack” Rackham ever flew, if he even flew one. The only record of any flag he flew is of a white one, probably as a French flag for deception. This doesn’t mean he never flew a black flag, but if he did we have no idea what it looked like. None of the witnesses at his trial mention a black flag.

Again, as noted above, the black flag attributed to him, with skull (“death’s head”) and crossed cutlasses (or hangers or falchions) is a 20th century invention. More on this in a moment.

Rackham was a smalltime pirate who whose piracies prior to late 1720, if any (although likely; “Charles Johnson” claims he was once Charles Vane’s quartermaster), cannot be corroborated, and he would doubtless be entirely forgotten today were it not for two women who briefly sailed with him, Anne Bonny & Mary Read, and a publisher/editor, apparently Nathaniel Mist, who greatly “sexed up” their petty sea thieving. For most of his time in command, Rackham’s crew numbered only ten, including the two women and himself; he had added nine more drunk volunteers earlier the same day he was captured at sea. His piratical cruise lasted less than two months. It’s entirely likely that even his nickname, “Calico Jack,” is an invention: the moniker does not show up anywhere in the historical record except in Johnson’s book (and he invented many details in his book), unlike, for example, that of Edward Teach/Thache aka Blackbeard, which does show up regularly in the historical record.

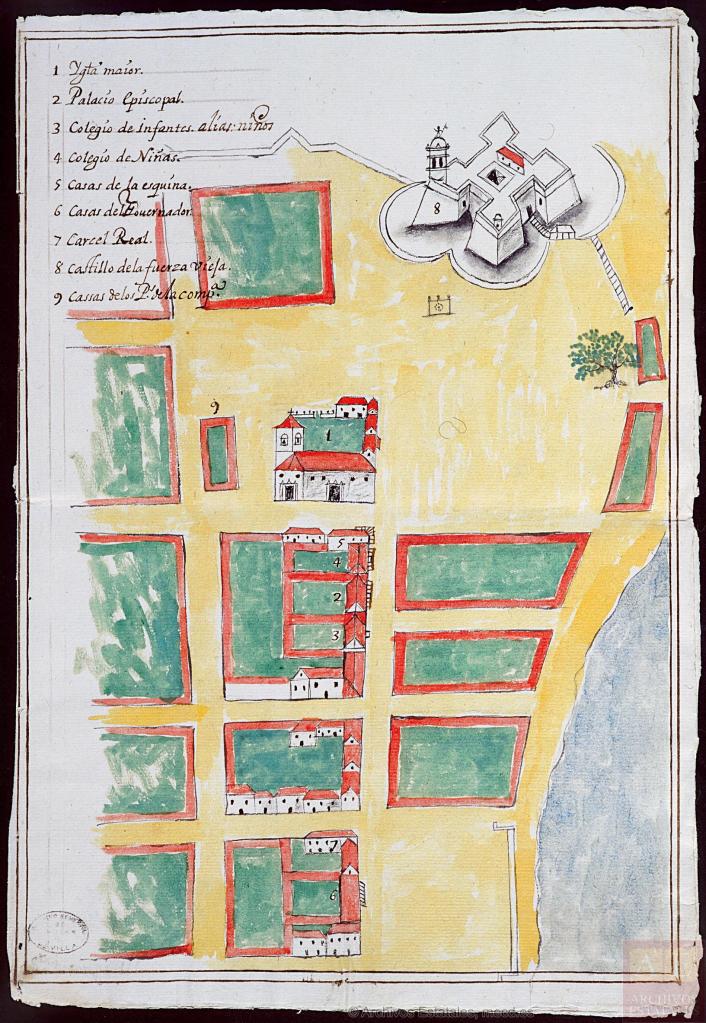

At the time Rackham sailed with these women in his crew, he commanded a tiny 12-ton sloop named William he stole at anchor at New Providence (Johnson reimagined it as a swift 40 ton sloop), and was robbing small largely defenseless fishing and trading vessels in the waters off New Providence, Hispaniola, and Jamaica: seven small fishing boats, three merchant trading sloops, one small merchant schooner, and one small canoe. Most if not all of them were local “Mom & Pop” coastal seafarers, in other words. Hardly epic escapades. None of the vessels Rackham captured put up a fight.

Bonny & Read wore women’s clothing aboard, and dressed as men only the very few times they robbed small merchant traders and fishermen. In fact, there is only one confirmed attack in which they dressed as men, although it is probable they also did when capturing other vessels.

There was only one battle in which the two women pirates might actually have fought side by side–the battle in which they and Rackham were captured–and it was over in a moment, literally. There wasn’t much of a fight other than a single “great gun”–apparently in this case a swivel gun, not a carriage-mounted gun–and possibly a pistol fired by the pirates, and neither did any damage. There is no record of any other resistance by the two women pirates or any of the men. The pirates surrendered immediately after Jonathan Barnet’s sloop fired a broadside and volley of small arms. No pirates are recorded as having been wounded or killed in the brief action.

Further, most of what “Charles Johnson” wrote about Bonny & Read cannot be corroborated in spite of extensive research by numerous scholars and other researchers. Although much of what “Johnson” wrote about pirates in general is clearly factual and has been corroborated (pistols hanging from silk slings is an example of what might be invention proved to be a fact by the Whydah wreck, for example), he also embellished–lied–often, almost certainly to improve sales potential. His depiction of Bonny and Read as the only pirates willing to fight while the rest were drunk below deck, and Bonny’s scornful upbraiding of Rackham as having failed to fight like a man, were surely invented or grossly exaggerated by the author.

As for the modern origin of the flag, I’ll quote from the draft manuscript of The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths (I’m too lazy to pull up the published final):

“Many…pirate flags depicted today, such as those purportedly of Stede Bonnet, Calico Jack Rackam, and Blackbeard, are modern inventions without historical basis. The pirate flag we know incorrectly as Calico Jack’s, with crossed cutlasses under a skull, may well have been inspired by the flag used in the 1935 film version of Captain Blood, that of a pair of cutlass-holding arms crossed beneath a skull. And this film flag may have been inspired by the early flag of Bartholomew Roberts, that of a death’s head and an arm holding a cutlass, or by the Dutch red battle ensign with an arm holding a cutlass, or by the seventeenth century flag of Algiers (a notorious have of Barbary corsairs), or even by a Barbary corsair flag of no quarter.

“We simply do not know what the pirate flags of these three pirate captains really looked like…except that Blackbeard’s was a black flag with a “death’s head,” and not the commonly attributed black flag with horned skeleton [apparently a very early 20th century invention]. Similarly, the purported pirate flags of Christopher Moody and John Quelch are misattributions: Moody’s is actually the Barbary corsair flag of no quarter described later in this chapter, and Quelch never flew a pirate flag…

“The origin of our modern popular but fanciful renditions is a series of several books whose illustrations were passed from one to the next, with few or any changes. The earliest publication of this series discovered to date—and probably the origin [except for the fanciful Blackbeard horned devil flag which was published previously in The Mariner’s Mirror]—is Basil Lubbock’s The Blackwall Frigates, published in 1922. The book includes a plate of eight pirate flags (even though the Blackwall frigates only came into being a century after the Golden Age of Piracy expired, but pirate flags sell books), three of which are misattributions, although otherwise mostly accurate, and one is a fanciful flag taken from an illustration in Charles Johnson’s pirate chronicle. [Rackham’s purported flag is not among them.]

“Most of these flags, with names now added, were reproduced in Charles Grey’s Pirates of the Eastern Seas. Patrick Pringle’s Jolly Roger: The Story of the Great Age of Piracy, published two decades later, includes nine pirate flags, all reproduced exactly from Grey’s book. In 1959, Hans Leip’s Bordbuch des Satans (Log of the Satans) includes some very similar flags clearly inspired by Lubbock, Grey, and Pringle, although two have been miscaptioned. Leip also adds three new flags, all imaginary: those of Calico Jack Rackam, Stede Bonnet, and Henry Every [“Long Ben”]. [Every’s flag includes a skull with a bandana and earring, a clear giveaway that it’s an invention.]

“Most of Leip’s pirate flags were reproduced exactly in 1961 in Pirates of the Spanish Main, part of the American Heritage Junior Library, with credit to Leip’s book. Pirates of the Spanish Main became a classic source of historical pirate lore—and mythical pirate flags—to literally thousands of young readers who imagined themselves pirates, not to mention to publishers of subsequent books on piracy. Similarly identified flags, some accurate, some, like those in the other books, not, were published in 1978 in Pirates, a title in the popular Time-Life “The Seafarers” series [including the “Calico Jack” flag with crossed swords]. It is no surprise that inaccurate images of pirate flags would appear in pirate books: for many publishers, the main purpose of images in a book is to get readers to buy it. The image of the “Jolly Roger,” whether accurate or not, is the perfect lure.”

The two most similar written descriptions of historical black pirate flags circa 1715 to 1730 to Rackam’s purported flag are “this flag was a black cloth in the middle of which was depicted a cadaver [skeleton] and scattered bones and crossed sabers” (I’ve translated this from French), and “The Ship hoisted a Black Flagg at the Main-Top-Mast-Head, with Deaths Head and a Cutlass in it…” Neither were hoisted by Rackham. The former is the only reference I’ve found to crossed swords among the many eyewitness descriptions of pirate flags.

If there were an early 18th century origin to the Rackham flag, we can blame Daniel Defoe’s Captain Singleton, a pirate novel published in 1720: Captain Bob [Singleton] flew “a black flag, with two cross daggers in it.” We cannot be certain this is the ultimate origin, for the idea of crossed swords is quite common throughout history.

Soon after I posted this blog, my friend Antón Viejo Alonso mentioned to me that conquistador, traitor, sociopath, and murderer Lope de Aguirre is said to have had three identical flags made in 1561, each with a black field with red crossed swords, the colors representing the blood he shed and the “lamentations and mourning” he caused. Whether this may have influenced Leip’s illustrator is unknown. Many flag designs appear to be parallel developments independent of previous or current similar flags, and not descendant, although clearly many also fall into the latter category. Black flags, and mortuary symbols on flags, have been around since antiquity, and have been used on land as well as sea. Aguirre’s flags were described by Friar Pedro Simón (1574 – circa 1628). The English translation of his work is entitled The Expedition of Pedro de Ursúa & Lope de Aguirre in Search of El Dorado and Omagua in 1560-1 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1861). A modern reprint is also available.

The modern “Calico Jack” flag of skull and crossed swords is a popular one in pirate films and among pirate fans. I myself own versions in both black and red, but I don’t represent them to be authentic. It’s an easy flag to imagine, substituting crossbones for crossed swords. I can even imagine myself creating it today or three centuries ago, or even today, given my interest in piracy and swordplay.

The “Calico Jack” flag has been used in several films, and a possible, even likely inspiration for its use in pirate movies, including the Disney franchise, is the flag flown aboard the pirate ship Wicked Wench in the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction at the Disneyland theme park. In fact, the design is also used early on in the ride in the form of a talking skull, with crossed cutlasses beneath it, providing safety and other information to visitors.

Very likely, the ride’s designers selected the design from the book The Pirates of the Spanish Main (1961) discussed above, although it is possible the Captain Blood film flag was also part of the inspiration. In fact, the entire ship-attacking-fort scene in the attraction was copied from the similar scene in the film. In fact, the Wicked Wench pirate ship on the ride appears to have been based on the Arabella from Captain Blood. (Carrying the hypothesis further, is the name Wicked Wench a bit of a joke on the Arabella–the name of Captain Blood’s ship–and the very proper English lady whose name it was? This would be in keeping with the piratical sense of humor of the attraction’s designers.)

All of this suggests that the Wicked Wench was the first fictional, and for that matter, non-fictional as well, ship to fly the “Calico Jack” Jolly Roger–although arguably the Arabella of the film Captain Blood did so in its original form. It’s entirely possible therefore that all subsequent film pirate ships flying the flag may have been inspired in part by the flag flown by the Wicked Wench, which was in turn inspired by the book The Pirates of the Spanish Main, and ultimately by the film.

(Historical note: buccaneer ships, one of which the Wicked Wench was originally depicted as, rather than as the pirate ship which would become the Black Pearl, did not fly black flags with skull and bones–only those of later pirates did.)

In Swashbuckler (1976), a version of the flag with ensanguined cutlasses is shown flying at the masthead of the Blarney Cock in the film, and flying in a odd arrangement at its stern in the movie poster and other marketing materials. The film stars Robert Shaw, Genevieve Bujold, James Earl Jones, Peter Boyle, Beau Bridges, Geoffrey Holder, Avery Schreiber, and, in an early role, Angelica Huston:

Likewise in 1976, the Black Corsair (Il Corsaro Nero) flew the black with skull and crossed swords. The film, an Italian B-movie pirate escapade, did at least show some Native American canoes as they were used by both pirates and Native Americans, was filmed at Cartagena de Indias, and showcased a bit of nice classical Italian swordplay.

Captain Thomas Bartholomew Red (Walter Matthau) flew a version in Pirates! (1986) aboard the captured Spanish galleon Neptune:

The flag was used in the 1986 BBC made-for-television pantomime of George MacDonald Fraser’s 1983 comic novel The Pyrates. Although much-abridged and with some stellar characters and major scenes missing, the version nonetheless captured the Fraser’s delightful manic comedy.

Morgan Adams flew the “Calico Jack” banner aboard the Morning Star in Cutthroat Island (1995); “Hoist the colors!” she orders at the beginning of the battle with Dog Brown’s Reaper. The flag flown from the Morning Star was slightly modified from the original 20th century illustration, although the popular “original” was used on posters and other promotional materials. The film, although it bombed at the box office (odd that a blockbuster is a film that makes lots of money, yet a blockbuster is also a very large bomb…), has a great soundtrack, plenty of comic book pirate action, and Geena Davis did a better job portraying a pirate captain than many men have in films.

The black banner with skull and crossed swords, though behind the skull rather than below it, is seen in the video game The Curse of Monkey Island (LucasArts, 1997) in the Smuggler’s Cave on Skull Island, as a table cloth where King Andre and his idiot henchman Cruff sit. An homage to Cutthroat Island, perhaps? There is treasure in a cave, after all.

A variation of the flag was used flown Escape From Monkey Island (LucasArts, 2000) at the masthead of Governor Elaine Marley’s pirate honeymoon ship. Notably, it resembles the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean icon used on the ride (see farther below).

The iconic flag was also used in Peter Pan (2003) as both a traditional Jolly Roger and as a sail decoration, notwithstanding that sail decoration, with the exception of an occasional Spanish fishing vessel and similar, had for more than half a century been abandoned by the late 17th and early 18th centuries which provided the piratical source material for Mr. Barrie and Peter Pan (or Peter and Wendy if you prefer).

It was flown aboard the Black Pearl in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003) at the beginning of the film when Elizabeth Swann imagines she sees the ship in the distance as she holds up a cursed Aztec coin, probably because this was the flag originally flown aboard the Wicked Wench, which was via a rather extreme revisionism converted from a buccaneer ship raiding the Spanish Main to the former name of the Black Pearl, associated with some East India Company nonsense (a company that never traded to the Caribbean).

It was flown again aboard the Black Pearl it in Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (2007) during the “Hoist the colors!” scene–again, a badass female pirate gives the order–and in the engagement following:

The “Calico Jack” skull and crossed swords also appears in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017) on the main-topsail of the Queen Anne’s Revenge, now commanded by Capt. Barbossa. The sails are of wine red or burgundy velvet with yellow-gold tassels, probably an homage to or inspired by the reputed sails of some the wealthiest Cilician pirates in antiquity. Some even captured Julius Caesar, who, after ransoming himself, had the pirates captured and put to death.

That said, author George MacDonald Fraser in his comic novel The Pyrates (1984 US edition) described the sails of the Grenouille Frénétique (the Frantic Frog), commanded by Happy Dan Pew, as having “velvet sails…fringed with silk tassels in frightful taste…” In fact, Barbossa’s “bon vivant and gourmet” image in Dead Men Tell No Tales might well have been inspired by Fraser’s description of Happy Dan Pew.

The “Calico Jack” flag is depicted also in the Starz Black Sails series at the very end of the final season. I was the historical consultant for all four seasons, and for reasons of both history and legal liability I traced the origin of the purported Calico Jack flag for the producers — and especially for the lawyers. The writers wanted to use the flag because it was already popularly attributed to Rackham, the set designers wanted something that looked authentic, and the lawyers wanted to be sure there was no copyright or trademark infringement.

A version was used in Lego Scooby-Doo! Blowout Beach Bash (Warner Bros., 2017). Scooby-Doo has always been fond of pirates, or at least ghost pirates and fake pirates…

Such an icon is the flag that it shows up in modified but immediately recognizable form, here in the BBC’s Doctor Who episode, “Legend of the Sea Devils” (2022):

Navy SEALs sometimes wear a “Calico Jack” flag patch on their field uniforms. Often the flag’s skull has an eye patch, a variant based most probably on choice of vendor. If my memory is correct–for the record, I’m a former Navy SEAL–its use began in the very late 80s when “real world” VBSS operations (board and search operations) were put to use. I might be mistaken, however. Pirate flag patches weren’t yet a fad in the Teams I served in (ST-3, SDVT-1) in the 80s. Certainly the “Calico Jack” patch remains in use today by Navy SEALs. Luminox, maker of a watch used by Navy SEALs, even has, or had, a special limited edition (375 watches only, I think) Navy SEAL watch with a Rackam skull and crossed swords on its face, although notably not the most common design of the flag, at least on one version. (See below, I couldn’t get captions to work on the tiled images.) Other military special operations units have been spotted wearing the flag patch, or one similar, too.

[Self-Promotion Alert!] The “Calico Jack” flag is also on the cover of The Golden Age of Piracy. Again for the record, the publisher chose the cover. I had no real input, although I’ve no problem with it. It certainly stands out and gets attention, and that’s what dust jackets are supposed to do. It slipped my mind when I first drafted this blog post that the Polish edition also uses the “Calico Jack” flag. (Sorry, Maciej Studencki, for missing this the first time around!)

If you’re looking for more details on pirate flags–accurate details, that is–you can read the book above or Ed Fox’s Jolly Rogers, the True History of Pirate Flags (author given as E. T. Fox). Or better yet, both. 🙂

If you’re looking to fly the flag, try eBay, lots of vendors carry it. It’s also available in red, and in design variations as well. There’s also a “weathered” version in red. Plus there are patches, stickers, T-shirts, rings, cufflinks, and more. If you want to fly the flag regularly, plan to pay a little more for sturdier nylon and construction; in particular, look for fabric that’s fade-resistant (all flags fade eventually). If you want to make your own authentically, you’ll need wool bunting or, in a pinch, silk or linen.

When buying, remember, black means “good quarter if you surrender now,” which in practice means “surrender now and we might not murder, torture, or abuse you much,” and red means “no quarter, we’re going to kill you all.” Perhaps the best description of the meaning of the red flag of no quarter comes not from my books, or any other book on piracy, but from Les Aventures de Tintin: Le Secret de la Licorne (Casterman, 1946; reprints in many languages; in English, The Secret of the Unicorn). Enjoy! Don’t read French? “Tonnerre de tonnerre de Brest!” It’s never too late to start learning another language! Or, buy the English version. It’s a fun read, and there’s a sequel too.

Copyright Benerson Little 2021-2025. First posted June 18, 2021. Last updated April 4, 2025.

The Women in Red: The Evolution of a Pirate Trope

With news that Disney is planning a new standalone pirate film starring a female pirate, it’s time review what has become a pirate trope: the woman in red, specifically, or at least often, a redhead. Why this trope in regard to a new Disney film? Because speculation has it that the film will be tied to Redd the Pirate above.

UPDATE: According to Margot Robbie in the press on November 14, 2022, Disney has killed the project, although rumors periodically surface that Disney continues to look at continuing the franchise, including a film with a female protagonist. A pity indeed that the rumored Robbie film was cancelled, it might’ve been quite the film. Certainly the genre needs a new female-led pirate film hearkening back to the Golden Age of Piracy and Pirate Film. There have been only a few made. Shout-out to The Pirates (2014), a Korean comedy-drama about Korean pirates, with strong overtones of the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, starring Son Ye-jin. (And please let it not be about Anne Bonny! See below…)

In the meantime while waiting for a new pirate film with a female lead, we’ll take a quick look at some of the myths and realities of female pirates during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy in the Americas from roughly 1655 to 1730.

The obvious apparent origin of the woman in red (a “scarlet woman”?), at least in terms of pirate fiction and film, is the Redhead in line in the bride auction–“Take a Wench for a Bride”–in the original version of the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean attraction in which drunken pirates shouted, “We wants the redhead!” Forced marriage, in other words, and all of its associated crimes.

Notably, text on the back of the publicity still describes the scene as an auction: “Gold-hungry pirate captain puts the town’s fair maidens–and the ones not so fair–on the auction block for his rowdy crewmen.” Thankfully, things have somewhat changed since then, tongue-in-cheek humor or not.

The Disney auction scene was doubtless inspired by scenes in The Black Swan (1942), Anne of the Indies (1951), and, in particular, Against All Flags (1952), in which captured women are portrayed as captives to be sold or given away as plunder. Both Anne of the Indies and Against All Flags have auction scenes of female captives, and the latter has an auctioneer with whip-in-hand as in the Disney attraction.

When it first opened in 1967, the Disney attraction was intended as–and in fact was–a tongue-in-cheek, lighthearted, swashbuckling film-based version of buccaneers sacking a hapless Spanish town in the Caribbean. Marketing text associated with early publicity stills noted that the ride was a “thoroughly realistic re-creation of buccaneer days.”

To enjoy the ride–which I did and still do–requires viewing it as a fantasy rather than a depiction of reality, for the reality of buccaneer attacks in the seventeenth century was anything but romantic to the victims: torture, rape, murder, and the enslavement of free men, women, and children were common. Documentary evidence of what today would likely be defined as resulting PTSD, among both victim and perpetrator, exists.

Like most of our fictional and cinematic adventure, we tend to sanitize or ignore facts in order to help create a fantasy more amenable to entertainment. Humans have done this for millennia. And there’s often nothing wrong with this unless we confuse the fantasy with the reality, which unfortunately happens all too often.

Today, the ride has been modified somewhat to both fit with the Disney pirate films, which are only loosely inspired by the attraction, and to bring the attraction up-to-date with current social mores. The latter changes have generally been a good thing, I think, even if the changes are not historical (and a few I disagree with). The attraction is a swashbuckling fantasy, after all, not an accurate “Audio-Animatronic” documentary. I’m much less enamored of the changes in keeping with the film franchise.

The most significant of the changing mores alterations to the attraction was the conversion of the pirates-chasing-women scene into one of pirates-chasing-food, and the conversion in 2018 of the bride auction scene into one of conquered residents bearing possessions, perhaps as ransom, and of the famous red-dressed redhead showing a leg into a red-dressed redheaded female pirate standing guard (and still, after a fashion, showing a leg).

Personally, I prefer the new scene and new redhead, ancient passing pre-adolescent fantasies notwithstanding.

In general, as in the original trope-setting (and great fun to watch) pirate swashbuckler, The Black Pirate (1926), leading women in pirate films are usually depicted as the “tavern wench” or “exotic wench,” or other saucy secondary love interest; or the “swooning heroine;” or the “pirate woman.”

The “pirate woman” is usually by far the most interesting, although too often she, Hollywood-style, gives up piracy at the end of the film in exchange for true love. Or she dies in battle, her true love unrequited, her true love interest running off with the “good girl”–often the swooning heroine. At least Against All Flags with Maureen O’Hara and Cutthroat Island with Geena Davis avoided this trope.

Sometimes the tropes are combined: Elizabeth Swann in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl goes from a nod at the literally swooning–via an over-tightened corset (“stays” to be correct)–heroine to pirate woman.

She also wears a red dress in the first film of the series, in scenes which combine multiple tropes: woman in peril, woman tied-up, woman with (airbrushed via CGI, reportedly) cleavage. The dress is a likely homage to the Disney attraction. A red dress also shows up on Scarlett, a tavern wench aka prostitute.

The red dress shows up in other pirate films as well, and as apparent copies or homages in Halloween costumes and video games.

Geena Davis stars in Cutthroat Island (1995, Carolco), and in one scene swashbuckles her way tolerably well with an anachronistic rapier and dressed in a red dress borrowed from a prostitute. The dress is clearly a nod, perhaps more than a bit humorous, at the Disney ride. In fact, Cutthroat Island often seems like one long string of pirate tropes, homages, and stolen scenes. Great soundtrack, though, and Davis does well as a pirate captain.

Now is a good time to briefly point out the reality of women pirates during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy 1655 to 1730. Strictly speaking, we know of only two who can be truly said to be pirates of the Caribbean: Anne Bonny and Mary Read, the former of whom gets all the cinematic glory while the latter, if what Charles Johnson wrote about her is true even in part, was the real swashbuckling bad-ass of the twain.

If Johnson’s early eighteenth century account is true, Read had been thrice a soldier in disguise, then a pirate, and even a privateer, in disguise, and reportedly fought at least one duel against a male crew member. Of course, this may be entirely an invention of the author, and his account of Read’s army service may have been inspired by the real life of female soldier-in-disguise Christian Davies. Although a fictionalized account of her life was not published until 1739, her story was known at the time Johnson’s pirate book was written.

Whether a true tale or not, it’s not Read’s warrior-woman story that ends up in fiction and film, but that of redheaded Anne Bonny–or at least she’s assumed to be redheaded because she was Irish and reportedly had a hot temper. Bonny gets all the glory, even though she may have been merely the girlfriend along for a joyride with her bad boy pirate boyfriend. Or not. Likewise Mary Read. We simply don’t know enough about her or Mary Read. Johnson may have invented the past histories of both to “sex up” his book for sales potential.

Of course, it’s entirely possible that both were as bold as Charles Johnson described them, even if they only dressed as pirates when attacking at least one vessel, and remained in women’s clothing otherwise. And their piracy was pitiful, nothing more than cruising in a tiny 12-ton sloop, not the 40-ton sloop Johnson described, and robbing a few “mom and pop” local trading vessels, including a canoe paddled by an old woman — hardly the stuff of Hollywood. Of course Johnson had to exaggerate for the sake of book sales!

Bonny, though gets all the attention, thanks largely to her relationship with “Calico” Jack Rackham. Writers are often lazy, and it’s easier to combine Read’s martial prowess with Bonny’s reported temperament and relationship with Rackham. However, not all writers who fictionalize the female pirate pair are as lazy. Some, including Erica Jong, have balanced their accounts of the two women.

But it’s Read, in my opinion, who deserves a movie.

Perhaps Anne Bonny, the assumed redhead, has also given us the redheaded part of the redhead in the red dress trope.

There are no other known women pirates of the Golden Age but for two who were technically pirates under the law, each having participated in utterly inept attempts at petty piracy, one of them comically so. Notably, two of the most commonly cited women pirates of the era were not pirates at all (please please please ignore Wikipedia!): Jacquotte de la Haye is entirely fictional, a creation entirely of author Leon Treich (Les Gentilshomes de la Flibuste, 1944, a factual-fictional account of buccaneers and some pirates written for a juvenile audience), and Anne Dieu-le-Veult, a wealthy widow, married the famous Laurens de Graff after his buccaneering days. She was never a member of his crew, nor is there any evidence that she was a member of any other crews. Treich is also responsible for exaggerating myths about Dieu-le-veult to an even greater degree, and even imaging deeds that never happened (including the utter nonsense that de Graff died in battle at her side).

More detail on Rackham, Bonny, and Read can be found here.

Likely though, there were real buccaneer and pirate women we’ll never know about because they remained in disguise. The common sexism of the day prevented women from becoming obvious members of a pirate crew. In fact, it’s probable that Anne Bonny and Mary Read (in Read’s case, after she revealed her sex) were part of John “Calico Jack” Rackham’s crew only because it was very small, no more than a dozen or so aboard a twelve-ton (that’s very small) sloop.

Pirates by majority vote could override their captains anytime but in action, and a larger crew would doubtless never have permitted women aboard as equals. In general, women were forbidden among early eighteenth century pirates except as prisoners, and even then pirates preferred to keep them away out of fear of indiscipline among the crew.

Red dresses pop up in other pirate or pirate-associated films as well, but it’s hard to tell if they qualify as tropes. Red is a popular dress color, after all: it stands out well and is often associated with temperament and sexual license, accurate or not.

In 1952’s Blackbeard the Pirate starring Robert Newton, heroine and damsel-in-distress Linda Darnell, in the scene most often used for advertising posters and lobby cards, is often depicted in red rather than the actual dark blue in the film. Clearly, there is marketing value in placing a woman in red clothing. In some cases she is even depicted as redheaded rather than as raven-haired as in the film and in life.

Honorable mention must go to pirate queen Black Sheba in George MacDonald Fraser’s comic novel The Pyrates (1984): “she donned her scarlet silk breeches and shirt, buckled her dimanté rapier at her hip, drew on her long Gucci boots, exclaimed at the state of her coiffure, clapped on her plumed picture hat, dapped a touch of Arpège behind her ear, and then spent ten minutes selecting one long earring and applying her lipstick.” She is by far the fiercest and sexiest of all the pirates in the book–a pirate queen as only a novelist or Hollywood could create.

A phrase in the novel, “dark and sinister woman…,” gives away part of her inspiration: she’s at least to some degree a female Captain Hook, the wordplay on the color of her skin notwithstanding. (“Proud and insolent youth,” said Hook, “prepare to meet thy doom.” “Dark and sinister man,” Peter answered, “have at thee.”) Even so, Fraser in the afterword describes the pirate queen as “a Dahomey Amazon with echoes of Lola Montez, Queen Ranavalona, and a pantomime principal boy.” Note also that the character of Bilbo–named for the slang term for sword (i.e. a blade from Bilbao, Spain) and not for the Hobbit–is according to the author, “Basil Rathbone playing a raffish Captain Hook.”

Also, at one point Fraser dresses one of the two more “traditional” heroines, Lady Vanity, in a maroon velvet dress, almost certainly, given his numerous other homages to piratical Hollywood and fictional tropes, in honor of classic pirate film heroines in red, and quite possibly of Disney’s woman in red as well. The dust jacket below shows another of the heroines, Dona Meliflua, also in red.

We might also consider the possibility that Nami from the One Piece anime, manga, and Netflix series was possibly inspired at least in part by the various redheaded pirate queens!

Nonetheless, Blackbeard the Pirate and other films (and novels!) notwithstanding, there is a possible ultimate origin for the redhead in red dress trope prior to the Disney attraction — in fact, its inspiration perhaps, or at least part of it.

In 1952 Columbia Pictures released The Golden Hawk, a pirate film, albeit one technically about French and Spanish privateers in the Caribbean in the late seventeenth century. The film is based on the novel by Black author Frank Yerby.

The male lead is Sterling Hayden playing Captain Kit Gerardo. His acting appears a bit wooden by Hollywood pirate captain standards until you read his biography: a true tall ship captain in his youth, later a Silver Star recipient and US Marine Corps officer assigned to the OSS (the precursor to the CIA covert operations department) behind enemy lines in World War Two. In other words, he was playing himself as a privateer captain. Even so, Variety magazine wrote that Hayden was “out of his element as the gallant French privateer…” Hollywood goes for (melo)drama, but most real captains are far more quiet and self-assured. They have to be. But I digress.

The female lead was red-haired Rhonda Fleming, one of the “queens of technicolor,” the most famous of whom was Maureen O’Hara who starred in several swashbucklers and whom some critics suggested would have been better in the role–and better for its box office.

Fleming’s character in the film is “fiery,” to be expected of the popular genre, including the Frank Yerby novel on which the film was based. In one scene–SPOILER ALERT!–she shoots Kit Gerardo when he makes “romantic overtures” to her, then leaps out a stern window and swims ashore. No swooning heroine she, thankfully, nor one to put up with sexual harassment or worse.

In a few scenes, Fleming, whose character’s real name is Lady Jane Golfin, wears a luxurious green dress. But in most lobby cards, tinted publicity stills, and movie posters, it’s red.

More importantly, Rhonda Fleming plays a buccaneer, Captain Rouge (that is, Captain Red)–she was also a pirate!

We may have simultaneously moved forward while also coming full circle. 🙂

Postscript July 22, 2020: This bears repeating: Please, please, please do not use the Wikipedia entry on women pirates for research! Or on any piratical subject! At least not if you’re looking for facts. 🙂 Wikipedia has a number of flaws in many of its articles on piracy (and in many other areas as well), including factual errors, incomplete information, inadequate or incorrect sources, trolling (intentional factual misrepresentation to trigger a reaction or otherwise for fun), severe ideological slants leading to inaccuracy (i.e. deliberate “scholarly” misrepresentation, often in support of social or political ideologies attributed to pirates, yet running counter to historical fact), and fairly constant regressive, incorrect changes to accurate information. Some articles on piracy are occasionally quite accurate, but many are all too soon revised inaccurately again.

Copyright Benerson Little 2020-2025. First posted July 8, 2020. Last updated October 22, 2025.

Jack Sparrow, Perhaps? The Origin of an Early “Hollywood” Pirate, Plus the Authentic Image of a Real Buccaneer

The small caption reads “Cover Drawn and Engraved on Wood by Howard McCormick.” Author’s collection.

The illustration above was created in late 1926 or early 1927, and published in April of the latter year. Among its several pirate clichés (skull and bones on the hat, tattoos, curved dagger, long threatening mustache) is one I had thought was entirely modern: a pirate hair braid with coins attached.

Quite possibly, this coin braid is the artist’s idea of a pirate “love lock.” The love lock was popular among some young English and French gentlemen in the first half of the seventeenth century. Usually worn on the left side, it was typically tied with a ribbon, a “silken twist” as one author called it. Occasionally two were worn, one on each side as in the image below.

Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt (1601-1666), known as “le Cadet la Perle” due to his bravery in battle. He is also sporting a pair of love locks. Print by Nicolas de Larmessin, 1663. British Museum.

This “pirate love lock” is a noteworthy characteristic of the very Hollywood, very fantasy pirate Captain Jack Sparrow, and I wonder if this image did not inspire much of his look. Historically-speaking, though, there is no historical basis for it among pirates of the “Golden Age” (circa 1655 to 1725), although it’s possible there may have been a gentleman rover or two who wore one during the first half of the seventeenth century–but not a braid or lock with coins.

Of course, much of The Mentor pirate image above was clearly inspired by famous illustrator and author Howard Pyle, as shown below.

Romantic, largely imagined painting of a buccaneer. From “The Fate of a Treasure-Town” in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1905. The image is reprinted in Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

“How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas,” Howard Pyle, Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899, a special two-page image. I’ve discussed this image in Of Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar Smoking Women.

A classic Howard Pyle line drawing, from Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

There’s a hint of N. C. Wyeth too, not surprising given that he was a student of Howard Pyle. However, Captain Peter Blood was a gentleman pirate, and the pirate on The Mentor cover is clearly not.

Battered dust jacket from the photoplay edition of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini, 1922. The cover art and identical frontispiece artwork by N. C. Wyeth.

And Wyeth’s Captain Blood cover is clearly influenced by this 1921 cover he painted for Life magazine. In fact, less the goatee, the two buccaneers might be one and the same:

Details about the painting can be found at the Brandywine River Museum of Art. Oddly, the Life magazine issue has no story or article about buccaneers or pirates.

“The Pirate” by N. C. Wyeth. Pretty much the same pirate as immediately above, less the fictional “pirate boots,” this time painted for Hal Haskell Sr., a Dupont executive who commissioned it in 1929. For years the painting hung in Haskel’s yacht, and afterward to the present in the family home. The print is available from The Busacca Gallery, Art-Cade Gallery, and other vendors.

The Pyle influence continued through the twentieth century in film, illustration, and mass market paperbacks about pirates…

“Pirate Dreaming of Home” by Norman Rockwell, 1924. The painting is also clearly based on Howard Pyle’s famous painting, “The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow,” and may be intended to represent the same buccaneer later in life, or perhaps is simply an homage to Pyle. (Norman Rockwell Museum.)

The Mentor illustration is also clearly influenced by Douglas Fairbanks’s 1926 film The Black Pirate, which was, according to Fairbanks himself, heavily influenced by Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates and to a fair degree by Peter Pan.

Seriously, check out Fairbanks’s costume in the film, it’s obviously that of Peter Pan grown up. I have a soft spot for Douglas Fairbanks: my first fencing master, Dr. Francis Zold, described him as a gentleman and a swordsman, and described how Fairbanks invited the Hungarian fencers to his mansion Picfair (named after Fairbanks and his wife, Mary Pickford) after György Jekelfalussy-Piller won the gold saber medal at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games. (N.B. I think Dr. Zold was referring to Fairbanks Sr. as a gentleman and a swordsman, but a nagging itch in my mind suggests that it was Fairbanks Jr. instead.)

Anders Randolf as the pirate captain in The Black Pirate. Note the skull and bones on the hat, the dagger in the mouth, the hoop earring, and, just visible, the tattoo on the chest. Screen capture from the Kino Blu-ray. A useful review of the film is available here.

Publicity still, possibly a frame enlargement from B&W footage given the grain, of the admirable duel on the beach between Randalf and Fairbanks, choreographed by Fred Cavens. More on this in a later blog post. Author’s collection.

And here, finally, we have Johnny Depp as Jack Sparrow in the flesh, braids and such dangling from his hair, again for which there is no historical precedent among Golden Age pirates that we know of. It’s hard to see how Depp’s costume, in particular his hair, might not have been influenced by the illustration at the top of the page. If it weren’t, it’s quite a coincidence.

“Captain Jack Sparrow makes port” from the Jack Sparrow Gallery on the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean website.

Jack Sparrow again, with a closer look at his braids &c. from the Jack Sparrow Gallery on the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean website.

As noted, it’s entirely possible that the Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl costume designers never saw the image at the top of the page. They may have imagined it themselves, or been influenced by something else. A very likely possibility is Donald O’Connor in the 1951 film Double Crossbones, a campy pirate comedy that makes fun of nearly all pirate clichés.

Donald O’Connor in Double Crossbones. Note the braid over his right ear. (Screen capture.)

Although this may seem to be little more than coincidence, there are other similarities between the two films, strongly suggesting the writers and costume designers were familiar with it. In particular, O’Connor plays a shy, somewhat bumbling shopkeeper’s apprentice in love with the governor’s beautiful ward, and she with him. Due to difference in social class he’s unwilling to express his love openly until by accident he becomes a pirate. Sound familiar? Even the costumes of the governor’s ward (Lady Sylvia Copeland, played by Helena Carter) are similar (homage-fashion?) to those of Elizabeth Swann, played by Keira Knightley. If not the Pirates of the Caribbean costume designer, then perhaps the Double Crossbones costume designer was familiar with the image at the top of the page.

Screen captures from Double Crossbones, 1951. Plenty of candlesticks, not to mention a painted miniature around the neck instead of a magical Aztec coin.

And there’s another film possibility: Torin Thatcher (a pirate’s name if ever there were!) as Humble Bellows in The Crimson Pirate (1952). Bellows wears a love knot, perhaps to compensate for his balding pate. It’s surely better than a comb-over! Disney may have been inspired by Bellows’s coiffure, for, like Double Crossbones above, there are numerous homages, shall we say, to the film in the Disney franchise, ranging from the way soldiers march to the “walking boat underwater” scene. It’s also possible that Donald O’Connor’s ‘do inspired Bellows’s.

Torin Thatcher as Humble Bellows in The Crimson Pirate (1952). Blu-ray screen capture.

Of course, all this so far is “Hollywood,” for lack of a better term. There are a number of serious groups of reenactors, scholars, and others trying to correct the false historical image, all with varying degrees of accuracy, agreement and disagreement, and success.

Hollywood has yet to get aboard, no matter whether in pirate films and television series, or often any film or television set prior to the nineteenth century for that matter, probably because it’s easier to play to audience expectations (and, unfortunately, much of the audience doesn’t really care), not to mention that there’s a tendency or even a fad among costume designers to do something that “evokes” the image or era rather than depict it accurately, not to mention the time and other expense of researching, designing, and creating costumes from scratch when there are costumes “close enough,” so to speak, already in film wardrobes.

Here’s a hint, Hollywood: you can start by getting rid of the “pirate boots.” They didn’t exist. They’re actually based on riding boots, and a pirate would only be in riding boots if he were on a horse–and horses aren’t often ridden aboard ship. Further, you can get rid of the baldrics in most cases, exceptions being primarily for gentlemen pirates wearing smallswords into the 1680s, no later. (You can have some Spanish pirates with rapiers wear baldrics after this, though.) And for that matter, you can get rid of wide belts and large belt buckles too. But if nothing else, please, please get rid of the boots, which, if I recall correctly, a UK journalist once correctly described as nothing more than fetish-wear.

Full disclosure: I was the historical consultant to Black Sails, a great show with a great cast and crew, but I had nothing to do with the costuming, much of which is considered as near-blasphemy by advocates of historical accuracy in material culture in television and film. That said, the show is a fictional prequel to a work of fiction that variously created or expanded some of our biggest myths about pirates–buried treasure, the black spot, and so on. Looked at this way, if you can accept the story you can probably tolerate the costuming.

I’ve discussed what real pirates and buccaneers looked like several times, not without some occasional minor quibbling by other authorities. The Golden Age of Piracy has some details, as do two or three of my other books, but several of my blog posts also discuss some of the more egregious clichés, with more posts on the subject to come.

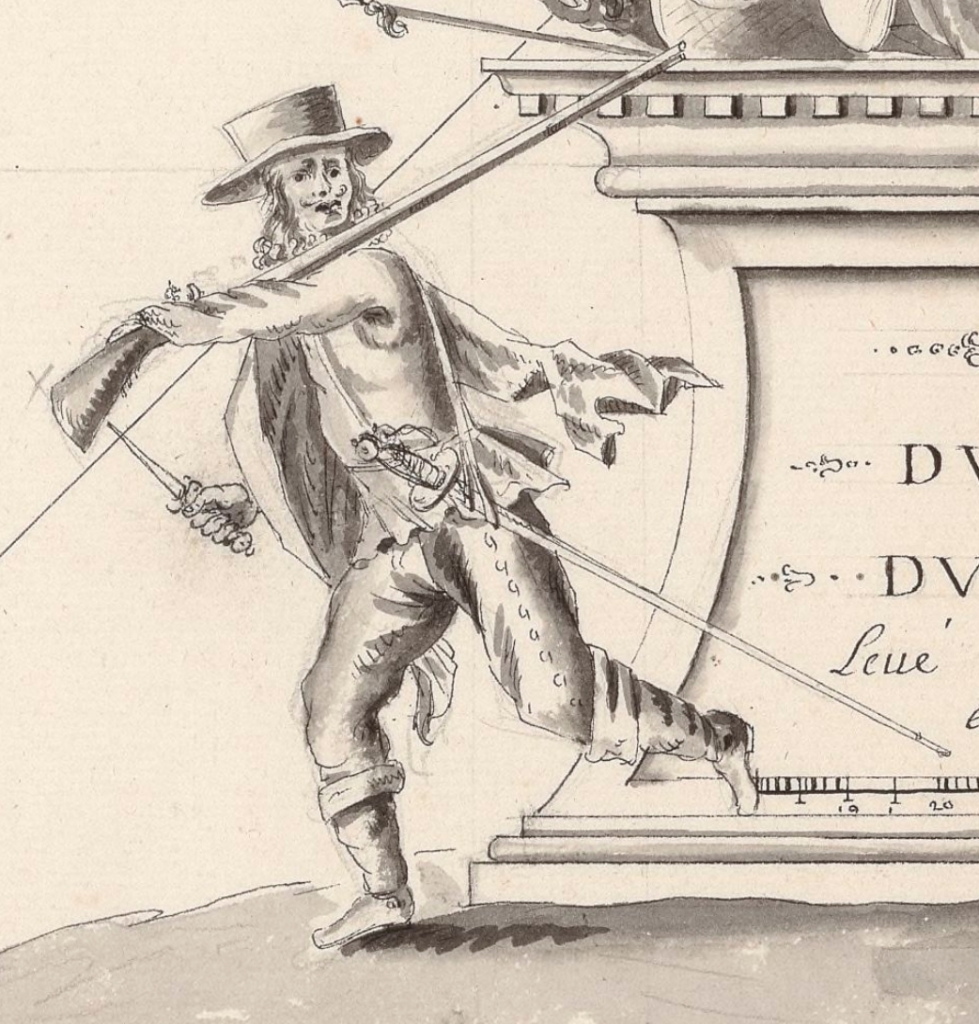

At any rate, here’s an image of a real buccaneer, a French flibustier in fact, from the 1680s. It’s an eyewitness image, one of only a handful of authentic eyewitness images of “Golden Age” sea rovers. It and the others prove that an image may evoke swashbuckling pirates while still being entirely accurate.

One of several eyewitness images of French flibustiers (buccaneers) in the 1680s. These are the only known eyewitness images of Golden Age sea rovers. They went largely unnoticed and without commentary until I ran across them by accident while researching late 17th century charts of French Caribbean ports. I’ve discussed them in an article for the Mariner’s Mirror, and also in these two posts: The Authentic Image of the Real Buccaneers of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini and The Authentic Image of the Boucanier. The posts include citations to the original images.

Copyright Benerson Little 2018. First published January 23, 2018. Last updated April 4, 2018.