Home » Posts tagged 'Tobacco'

Tag Archives: Tobacco

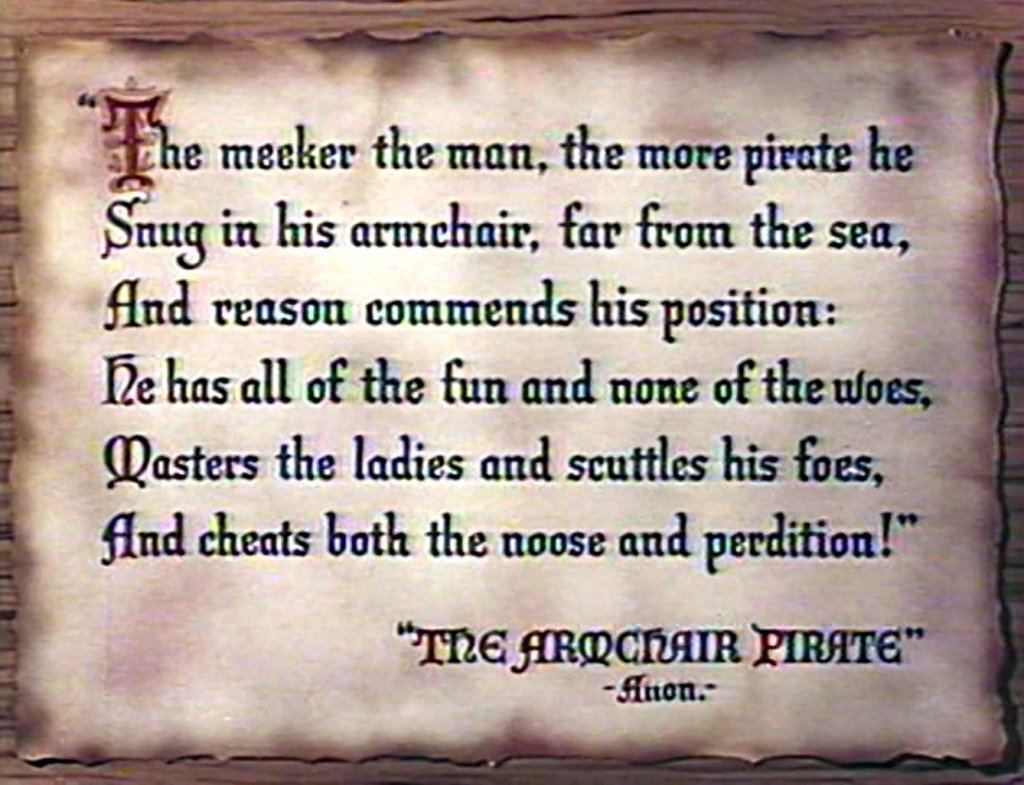

Creating that Ship-at-Sea Sensation While Armchair Adventuring: Some Progressively Tongue-in-Cheek Suggestions

A practical, yet certainly tongue-in-cheek, post about creating a buccaneering sensory environment while reading Captain Blood in your armchair, playing Blood & Plunder or Oak & Iron or a buccaneer board game like The Pirate Republic with your friends, watching The Sea Hawk or any other classic sea roving swashbuckler, playing a piratical video game (Sid Meier’s Pirates!, the Monkey Island series, AC Black Flag, Sea of Thieves, and Skull & Bones come to mind), or finally finishing that 1:48 scale model of a 17th century Spanish pirate hunting frigate (perhaps even the Cinco Llagas!) you started a quarter century ago…

Pine Tar & Cordage!

If there’s any single smell that evokes seaman’s “heart thrice walled with oak and brass”* during the golden age of sail, it’s pine tar. It was one of the principal naval stores, critical in the age of wooden ships. Unlike turpentine which was drained from pine tree trunks by notching them serially and collecting the sap, both in liquid form and as hard rosin (pine resin), then boiling it, pine tar was derived by stacking sap-rich pine wood from old growth trees in great heaps, burning it, and collecting the tar as it drained from the bottom. Pitch is simply pine tar further distilled to make it thicker. Pitch was used to seal the seams between planking after paying them with oakum, &c.

Pine tar was thinned with turpentine to preserve running rigging; in thicker consistency for marline; and even thicker for standing rigging. It was also used, often heavily thinned with turpentine and mixed with linseed oil or tallow, or both, for treating the planking on ships’ sides.

Its smell is, to those like me who love it, entrancing. Nothing evokes the old wooden ships like it does! But to those who hate it, those for whom organic smells cause them to recoil in nasal horror, it is akin to the combined smell of rotting road kill and hot roofing tar.

There are several excellent methods for bringing these scents about:

1. The simplest by far is to buy a tin of real pine tar–you can order it online–and open it, or better yet, pour a little bit into a small container and leave it uncovered. It doesn’t take much to fill a room with the smell. Sniff deeply from the container every quarter hour. Or dip your fingers in it and sniff them every so often–then wipe well unless you want your book or miniatures to smell like pine tar too.

2. Learn sail-making by making a ditty bag. You’ll need tarred marline, its smell will linger for months. Keep the bag nearby. When the marline eventually dries out, refresh it with a mixture of pine tar and turpentine.

3. Buy a ball of tarred marline, keep it in a plastic container so it doesn’t dry out over time, open it up as required for the salty tar smell. You’ll need it anyway for suggestion #2 above.

4. Bathe with pine tar soap. There are several on the market, Grandpa’s is highly recommended by many a tall ship sailor. Or just sniff the soap bar occasionally.

5. Treat your shoes with Huberd’s Shoe Grease, it’s made of pine tar and beeswax. Or just open a tin and sniff it periodically. And it really does work well waterproofing shoes, boots, gloves, and also cartouche boxes (for those of you who need to keep your powder dry).

6. Brew and drink Lapsang souchong tea–it smells, and even tastes (pleasantly, actually) of pine tar. Really, it’s much better than you might think, even if it’s anachronistic. It’s easy to find.

7. Hang a coil of marine grade Manila nearby, or better yet, several, or even better, hemp cordage if you can find it. Wet it for best effect. Or, the next time you’re by the seaside, soak it for a couple of days in the ocean, let dry, then hang and sniff as desired.

8. If you want to add more authentic smokiness, light a wood fire to augment the pine tar smell with that of the fire-hearth in the cook-room (NOT galley, that’s a later term). Place a pot of cornmeal (ideally heritage grits which are just cornmeal ground from heritage corn, a much-different and more authentic flavor, but any coarse stone-ground cornmeal will do, and even polenta, yellow grits, &c are close enough) and water on the fire to boil, add bacon fat or, better yet, unrefined manteca (pork lard), to season. Serve with boiled boucan (you’ll have to smoke your own boucan first, you can’t buy it at the market). Or, boil cornmeal dumplings (recipes on the Internet, they’re still made in some of the former English colonies of the Caribbean), known as doughboys by buccaneers), serve with unrefined manteca. When either or both are ready, dine like a buccaneer.

Be advised that, like most of these scents (or odors, depending on your sense of smell and olfactory triggers in your memory), your spouse or other significant other, unless a sailor or fisherperson, might not like them at all. You may hear about this, in fact. Nod with empathy, promise to keep the door closed.

Rum!

Pour a glass. Sniff. Drink. Repeat carefully. Don’t drive, neither ashore nor at sea, and don’t play with ANY firearms (a potentially fatal combination!) even unloaded, or sharp swords (you’ll stab your eye out for real, especially with a cutlass, or stick your foot to the floor/deck with a smallsword or rapier, the latter incident I’ve some experience with) while imbibing, nor afterward until the effects have passed!

I recommend dark molasses-ey rums: Pusser’s Gunpowder or just plain Pusser’s, Gosling’s, most any Navy rum, &c, or any amber or dark Jamaican or Bajan rum. I’m also partial to the Colombian Ron Viejo de Caldas with a pipe and tobacco (especially in a snow storm with thunder and electric blue lightning, of which there aren’t any in the Caribbean), and Smith & Cross, an authentic 18th to 19th century shipped-from-Jamaica-to-London style is also excellent. If you like a strong molasses taste, try Cruzan Blackstrap.

Lately I’ve become enamored of Privateer Navy Yard, a colonial New England style rum, and, for making punch, Plantation O.F.T.D and Ministry of Rum’s Hamilton 114, but note that this list changes quarterly. Also check out some of the strong pot-stilled, unfiltered, uncolored, “funky” white (often yellow, really) rums. We’re spoiled these days with the number of “funky” aka “hogo” rums these days, including white or yellow rums similar to 17th and 18th century rums, most of which were white or pale yellow and drunk very young. I highly recommend Hampden Estate Rum Fire Overproof. For a darker funky rum, try Doctor Bird Jamaica Rum, a late favorite of mine thanks to my son-in-law. (“Hogo” derives from “Haut goût” or “high taste” and denotes a strong molasses and other raw taste; in meat it indicates gaminess.)

If you’re a modern Cuban-American pirate, it’s going to be the original Cuban Havana Club (not the Puerto Rican stuff although I’ve nothing against it per se) and real Cuban cigars, or so I’ve been told by a modern Cuban-American corsario who introduced me to the combination. That said, it was the wife of a Hungarian who first introduced me to Cuban cigars, she’d smuggled (i.e. forgotten to declare, or so she said, to US Customs) them out of Hungary back in the days of the Iron Curtain. The authorities confiscated some of the cigars, but my friend had hidden others in another bag.

You might also try a 17th-18th century rum punch. The classic modern recipe is one of sour, two of sweet, three of strong, and four of weak, with a bit of grated nutmeg (or even allspice). Translated to the 17th century, this means one part key lime juice (preferred, although you may substitute orange or even pineapple juice), two parts muscovado sugar, three parts rum, and four parts water. Nutmeg was also commonly used in the 17th century. (See the foot of this page for notes on acquiring muscovado and key limes.)

If you plan on serving punch in a bowl, Charles H. Baker Jr. in his a famous drink book The Gentleman’s Companion: Being an Exotic Drinking Book… (1946) suggests chilling all ingredients first, and placing a large block of ice at the center of the bowl. Long gone are the days of ice trucks delivering blocks of ice to be chipped away in the ice box with an ice pick, but instead you can make a large block of ice by using a food storage container as a mold.

Tobacco!

Foremost, don’t smoke. And if you do, let it be only an occasional pipe or tobacco. And smoke outside — if you own your residence it will have better resale value, and your spouse or significant other might not murder you.

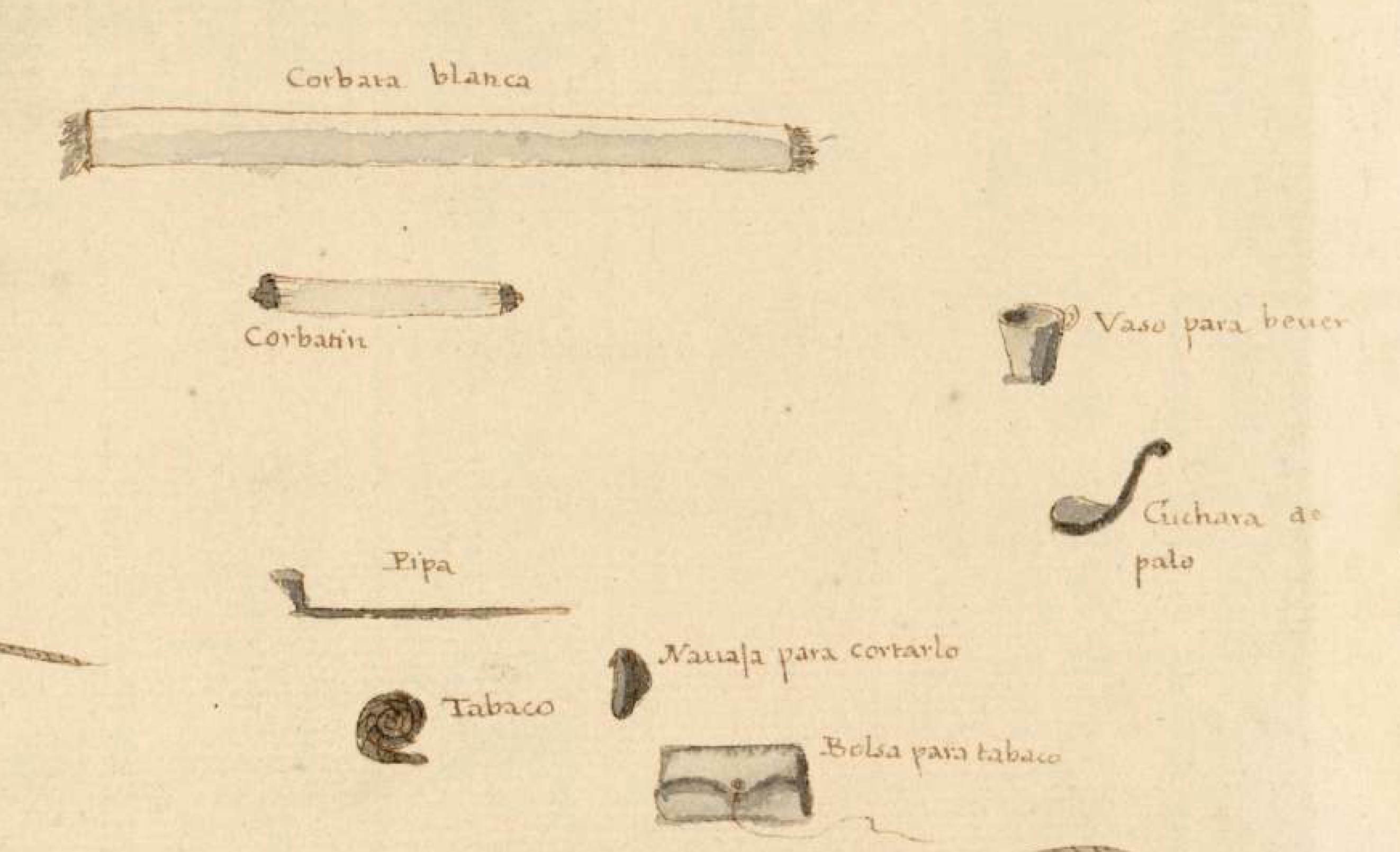

If you choose to smoke a pipe, try a high quality clay replica (a churchwarden is an excellent choice for you gentleman and lady buccaneers, but shorter pipes were more common shipboard), fill it with bosun’s rum twist (often called sweet rum twist), Sweet Virginia (Sutliff makes one), or Navy flake, and puff away. That said, I’ve been reliably informed that the early Oronoko (Verina, Sacerdotes, &c) and related Virginia tobaccos of the era were probably more like modern mild burleys.

Add an authentic replica of a seventeenth century pipe tamper if you like — a dolphin (aka dolphin fish, classical dolphin, mahi-mahi) or something bawdy, both of which were common along with other designs. (See Bucklecastings online for some.)

Or, smoke a cigar. Yes, cigars were popular in the 17th century Caribbean. Pretty much everyone smoked them to some degree, although pipes were more popular among the English, French, and Dutch. Cigars far outnumbered pipes among the Spanish, Portuguese, Africans, and, at least in the Caribbean and environs, Native Americans, and were smoked by women as well (as were pipes, by the way, among other nationalities), especially by Spanish women in the Americas. Check this out: Of Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar Smoking Women.

WARNING! Keep your pipe or cigar away from various flammable mixtures of pine tar, turpentine, beeswax, and linseed oil! Especially if you’ve been drinking rum!

WARNING! Keep your pipe or cigar away from your blackpowder, if any (see below), too! Blackpowder isn’t quite as sensitive to candle or common match flame as Hollywood depicts it, but a tobacco ember might still set it off. Put another way, it might take a dozen common wooden matches to ignite a blackpowder train — or it might take only one! And the flame from even a small amount of blackpowder can burn you to the bone! (Blackpowder, by the way, doesn’t explode, it deflagrates, if you want to get technical. It doesn’t burn as fast as true explosives.)

You can add a pipe bowl cover to your pipe for authenticity and, as was the case even three centuries ago aboard ship, for safety. It’s useful also when stalking wild cattle or feral swine on tinderbox arid coasts and desert islands. I recall my seafaring adventurer father using one when my brother and I would go hunting with him when we were in our early teens.

While smoking your pipe, take a break, tend your geraniums, and randomly shout, ideally from a window at passersby, “Quo, quo, scelesti, ruitis?” If you don’t get the allusion, shame on you! Go back to your armchair and do some more reading. 🙂

Blackpowder!

I’ve had my doubts about including this suggestion, given the large number of fools with firearms in the US these days. However, given that in my experience there are far fewer fools with blackpowder arms, I’ll go ahead.

WARNING! NOT NOT NOT FOR NOVICES OR AMATEURS! THIS IS NO JOKE! UNLESS YOU REALLY KNOW WHAT YOU’RE DOING, DON’T!!!

TRIPLE-CHECK that the barrel of your flintlock musket or pistol is UNLOADED. Prime (but do NOT load), point in a SAFE direction, bring to full cock, and squeeze the trigger — and thereby, assuming your flint is sharp and tight in the cock, fill the room you’re in with just enough smoke to bring your spouse or significant other down upon your ears after any nearby smoke alarms go off. Or maybe do this outside instead and hope your neighbors don’t call the police on you, which they probably will (and probably should, just in case) for discharging a firearm within city limits. Remember what I said about fools and firearms…

Breathe deeply of this broadsides and boarding actions smell. As an archaeologist at the Middelaldercentret in Nykøbing Falster, Denmark put it to me (we were testing firepots and an iron breech-loading swivel gun for a TV show), “There’s no one who doesn’t like the smell of blackpowder!”

If you like, afterward clash a couple of swords together afterward to suggest a boarding action. Prefer fencing swords rather than real cutlasses or functional replicas in order to avoid nicking sharp blades unnecessarily. If you’re going to nick edges, let it be in a real boarding action of which there really aren’t any of the age of sail sort anymore. Cue Jimmy Buffett…

WARNING! Don’t mix with rum drinking! Or any drinking! Or any other substance that impairs your judgment!

Sound Effects!

Put on music or videos of surf, preferably with seagulls in the background.

Or listen to a video (YouTube surely has some) of tall ship sounds–the sea, creaking rigging, seagulls.

Ignore this if you live by the sea or on a boat or ship (lubbers take note: a boat and a ship are not the same thing). If you live near a dump you might hear seagulls. Ignore the smell or pretend it’s the ship’s bilge.

You can always put on a CD of sea shanties, the bawdier the better in most cases, but accept the fact none are 17th or 18th century, but 19th & 20th century and therefore anachronistic. Or, put on a CD of John Playford’s popular 17th century tunes, there are at least two good compilations available. (Or stream them, I know, we’re well into the 21st century…)

If it’s Spanish pirating you want to evoke, try La Bamba: Sones Jarochos from Veracruz sung by José Gutiérrez & Los Hermanos Ochoa (a Smithsonian release). La Bamba was reportedly composed in the aftermath of the sack of Veracruz in 1683, lampooning the bombast of defenders who did nothing to stop the pirates — but claimed they would. Or, if it’s gentlemanly Spanish pirating you want to evoke, try Fantasía para un Gentilhombre by Joaquín Rodrigo, it has elements of Gaspar Sanz’s 17th century guitar compositions; or just sample some of Sanz’s music instead. Navigating Foreign Waters: Spanish Baroque Music & Mexican Folk Music is also an excellent choice.

But if it’s Hollywood pirating you want to evoke, put on Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s score for Captain Blood or The Sea Hawk, Alfred Newman’s for The Black Swan, Franz Waxman’s for Anne of the Indies, Max Steiner’s for The Adventures of Don Juan (I know, Don Juan isn’t a pirate film or even a seafaring one but the score was used in The Goonies aboard the pirate galleon), John Debney’s for Cutthroat Island, or, one of my favorites, the Chieftains’ score for the best version of Treasure Island ever filmed.

Hang a ship’s bell nearby, ring it loudly occasionally, ideally with the correct number on the half hour, remembering to ring in pairs: ding-ding, ding-ding, ding, &c. Unless you’re a complete fool, avoid doing so if your spouse or significant other has a migraine.

Note that sound effects are unnecessary if you’re just watching a movie…

That Salty Sea Smell!

It’s almost impossible to imitate, so go live by the sea if you can. Upside: the smell and sound of the sea. Downside: everything rusts, including your car. Failing this, keep a bottle of seawater handy, open it occasionally, and sniff. If that doesn’t work, attempt to reproduce that special salty sea smell with water, salt, and a few dead guppies.

Pitching, Sending, Rolling, & Yawing…

There’s really not much you can do to emulate the feel of a ship underfoot except to go to sea or get drunk or carsick. Best substitute: a hammock. Try not to fall asleep in it after drinking two rum punches. If you plan on inviting your significant other aboard the hammock, whether to recreate life aboard a man-o’-war in harbor or on a desert isle à la Robinson Crusoe, make sure it will hold both of you up! In other words, if you hang your hammock on an isle or cay, make sure your weight won’t pull one or both small trees over onto you. Experientia docet…

The Ship’s Head, Chamber Pots, Pissdales, & the Bilge!

Pretend you’re a buccaneer quartermaster or captain and use a bucket or chamber pot to relieve yourself because you’ve got too much status to use the ship’s head or one of the pissdales (if even there are any along the gun’l), or you’re too lazy to piss in the bilge where you shouldn’t anyway (the ammonia stench from this could actually choke seamen out at times). Pretend your spouse is your personal servant (yes, some buccaneers had indentured servants as their personal servants, and even naval officers often went to sea with servants, mustering many as seamen and taking part of their pay, a common practice of dubious legality) and ask her or him to empty said relief. Stand by for a break-up. Or simply for the contents to be emptied on your head. Personally I recommend passing on this simulation, but to each his, her, or their own…

More Effects of Sight and Sound: Parrots!

Get a parrot, name it Pol (it’s where the name Polly comes from, you can thank Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe), teach it to shout “Pieces-of-Eight! Pieces-of-Eight!” over and over (but this’s from Stevenson’s Treasure Island). Don’t listen to anyone who tells you parrots are just a fictional pirate trope — some pirate tropes actually have a great deal of legitimacy, particularly this one. Don’t believe me? Check this out: Of Pirates & Parrots (& Monkeys, Too).

However, be prepared for to spend big bucks to acquire and maintain a parrot, and also for guilt trips when the parrot won’t shut the hell up and you stuff it in the closet for a couple hours for some relief. Also, the damn bird will probably outlive you, so make sure to include it in your last will and testament. Leave it to someone who’ll take good care of it. Extra points if giving it to this person will also satisfy your need for petty personal revenge. Warning: acquiring a parrot is a serious undertaking! Best substitute? House-sit for a few days, parrot included.

And Still More: Monkeys!

Get a capuchin (monkey, not monk), put it in a diaper, name it “Captain,” and let it roam free and destroy your home. Or maybe not: primates shouldn’t be kept as pets, although some members of Homo sapiens — a primate species — inexplicably, even unconscionably, thrive on it (both keeping monkeys or other primates, including humans figuratively, as pets, and being kept as pets, that is).

Drawback: monkeys, not to mention many politicians and Internet windbags these days, often fling their turds at humans and can be quite obstreperous when it comes time to correct or prevent their bad behavior. (I’ll forgive monkeys but not politicians, pundits, or “influencers” aka product shills.) For what it’s worth, monkeys are another pirate trope with a great deal of maritime legitimacy. See the link above.

And If You’re Really Bold…

Just stuff the book you’re reading or the game you’re playing into your sea bag or sea chest, find a tall ship in the offing, and join her (its) crew!

Notes on Muscovado and Key Limes

Key limes are available in many groceries these days, including Walmart’s produce sections. Often the limes are listed as Mexican, given their usual origin, and they’re also known as West Indian limes. You’ll know them by their size, a third that of conventional limes.

For muscovado sugar, I recommend buying it in bulk from Amazon, it’s by far the best value, ten one-pound boxes, Billington’s Natural Dark Brown Molasses Sugar, or for a lighter taste, Billington’s Light Muscovado. (Colonial sugar plantations produced both dark muscovado and a lighter “clayed” sugar — in fact, sugar production was responsible for the majority of African slavery in the New World.) Much smaller quantities cost almost as much as do ten pounds in bulk. Billington’s also makes a Dark Muscovado but it’s hard to find in bulk in the US and is quite pricey in smaller quantities and in any case I can’t tell much difference between it and their dark brown molasses sugar — the latter tastes, looks, and cooks like muscovado, except that it has more molasses than the average muscovado, and has less of a floral flavor; most “experts” regard the dark molasses sugar as a form of muscovado. India Tree also makes a muscovado sugar, but prices vary widely; some groceries sell it for around six or seven dollars a pound.

Use dark or light muscovado sugar also for baking cookies, frying plantains with butter, making hot buttered rum (use Cruzan’s Blackstrap!), on oatmeal, &c, and for any other brown sugar need. This is the real stuff! You can also use panela, piloncillo, and similar “brick” or “cone” cane sugars to substitute for muscovado, they’re quite similar to 17th century sugars — in fact, they’re produced in much the same way and are generally considered as forms of muscovado. Dark muscovado is marketed in some areas of the world as Barbados sugar, although most today comes from Mauritius and the Philippines.

* Robert Herrick in “A Country-Life: To His Brother Mr. Tho. Herrick” (Hesperides, 1648) quoting Horace, Odes I.3 in translation.

Copyright Benerson Little 2022. First posted July 6, 2022. Last updated July 3, 2024.