Home » 2019

Yearly Archives: 2019

Holiday Greetings!

With the floor beneath the tree still looking like the decks of the Arabella just before she sank in her final swashbuckling action, here are a few lines in sweet memory of past Christmas mornings and in happy anticipation of future ones, at least for anyone who has ever pretended to be the pirates of fiction and film–or who inspires such fantasy in their children:

“Bars of gold and pieces of eight,

Spanish galleons of goodly freight;

Buried treasure to seek and gain:

Lads [and Lasses]! what ho, for the Spanish Main!”

–A. E. Bosner, The Buccaneers: A Tale of the Spanish Main

The Iconic “Spanish” Fort: Only a Spanish Galleon Says “Pirates” Better!

Recently, while searching for Spanish colonial Caribbean buildings and fortifications for a game table on which to play Blood & Plunder by Firelock Games–a project that will likely take me years but should be ready when my third and fourth children are old enough to play–I came across a truly iconic 28mm version of the classic Spanish fort by King’s 3D Prints, and I had to have it.

Why? Well, as I’ll explain in more detail shortly, because… Captain Blood. Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean ride. Classic Hollywood swashbucklers starring Errol Flynn and Maureen O’Hara and others. The intelligent buccaneer romances of Rafael Sabatini. And most especially, childhood memories.

Not to mention that I’m working on a fully-annotated version of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini, and it would make a great inspirational prop.

In the interest of full disclosure, let me say up front that I do historical consulting for Blood & Plunder (and Oak & Iron too). It’s a great game created by great people, with an emphasis on both enjoyable game play and historical accuracy. In fact, the creators of South Park love the game, and even featured it in episode 7, season 23 this past November 13 (2019).

But Firelock, which has a wonderful, beautiful, broad line of ships, vessels, figures, &c, doesn’t make a Spanish fort with the particularly iconic garita or sentry box (I’m not trying to put you on the spot, Mike!), and this is what really makes “Spanish” Caribbean forts stand out to me. And not just Spanish forts, but European forts in general, even though pirate movies make us think that all such forts are Spanish Caribbean, or in some minds, “pirate” forts.

So, again, when I found this 3-D printed Spanish fort, I had to have it. More full disclosure: the seller recognized my name, knew I had written books on the subject of piracy and consulted for Blood & Plunder, and said he loved the game, it’s what got him interested in the period. And he sent me more than I had purchased, with a tongue-in-cheek piratical request that, if I didn’t mind, I’d put a small plug in for his product.

I decided therefore that this was a good excuse for a blog on Spanish Caribbean forts, so here we are, plug included, and I’m happy to do so. The 3-D printed fort is a very nice piece of work, perfect for evoking pirates of the Caribbean, not to mention the brave men and women who tried to defend their lives and property against these often brutal sea thieves.

Most people are probably familiar with this iconic fort from the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean attraction. Originally meant to be a comic depiction of a the sack of a Spanish Caribbean town by not-too-rapacious buccaneers–although in reality there was nothing comical about these attacks–it has been somewhat altered to bring it in line with the film series. But no matter, we’re all familiar with the pirate ship Wicked Wench bombarding the Spanish fort, its sentry box in plain view, even though no pirate ship would ever have survived such a cannonade. Buccaneers attacked Spanish forts from the shore, not from the sea, and for good reason.

So iconic is the image of the sentry box that it’s displayed prominently at the entry to the ride at Walt Disney World, and even more prominently at the nearby Pirates of the Caribbean lodging, in which there are several at the pool.

The opening scene at the Disney ride, at least once you’re past the scenes of the dead or undead pirates, in which ship battles fort, was without doubt inspired by the similar scene in the 1935 version of Captain Blood starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland. In it, following the plot of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini, a Spanish pirate making a reprisal against English buccaneers launches an attack against Port Royal (although in the book it’s Barbados–screenwriter Casey Robinson streamlined the plot). But in reality, not even the most famous of all admirals, Michiel de Ruyter of the Netherlands, with a battle fleet at hand, could defeat the fortifications of Barbados, much less would he have been able to at Port Royal. It’s a fiction, albeit a fun one, which has been carried on by numerous swashbuckling novels, pirate films, and, especially, pirate video games, their arcade nature making such battles a natural fit.

The iconic Spanish fort made its way into other pirate films as well, such as The Spanish Main (RKO, 1945) below, starring Maureen O’Hara, Paul Henreid, Binnie Barnes (doing some excellent swordplay, by the way), and John Emery (also doing some excellent swordplay, much better than Henreid’s, notwithstanding that Emery had to lose to him in the finale).

Period depictions of the sentry box, used on forts across Europe actually, are more difficult to find.

In spite of a review of the plans of numerous seventeenth century Spanish Caribbean and other Spanish Main fortifications, the sentry box seldom shows up, although here it does in a somewhat inaccurate vista of Nombre de Dios.

And here’s a fort at Cumana, Venezuela, in 1704:

There are in fact three Spanish forts with the iconic sentry box–all very “piratey”–in the US, all worth visiting. Most impressive is the Castillo San Felipe del Morro in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico. The image at the head of this blog post was taken there in 1987.

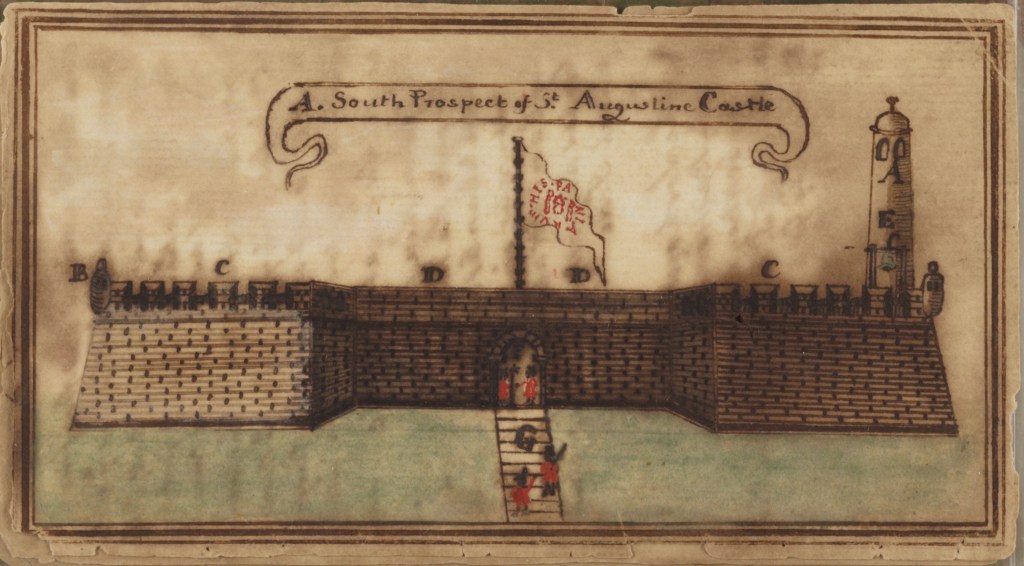

In St. Augustine, Florida, is the Castillo de San Marcos, a classic Spanish fort, one attacked both by buccaneers and by Carolinians in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

And nearby, at Matanzas, where the Spanish slaughtered an entire French colony in its early stages (in many ways a reprisal for French slaughter of Spaniards), is the Fuerte Matanzas, probably the coolest little fort in the world, evoking buccaneers and the Spanish Main close up. Every kid should have one!

There’s also a similar fort section, albeit a reproduction, at Fort Condé, or Fort Louis de la Mobile as it was originally known before it was relocated in Mobile, Alabama–French this time.

I know the Disney ride is fun and the Flynn film is outstanding entertainment, but I can’t recommend enough that you visit these forts in the US, and even better, visit those in the Caribbean and Latin America as well. For additional information, there are several good books on the subject of Spanish forts in the Americas, and I recommend starting with Fortificaciones en IberoAmerica by Ramón Gutiérrez, available as a print book and pdf as well.

And if you need a Spanish fort to set on your desk, well, you know where to find one!

Copyright Benerson Little, 2019. First published November 23, 2019, last updated December 11, 2025.

Swordplay Aloft: A Fictional But Entirely Enjoyable Pirate Trope

Cutthroat Island finale, Morgan Adams (Geena Davis, right) versus Dawg Brown (Frank Langella). Carolco, 1995.

Originally written in advance of my forthcoming series on “The Duel on the Beach,” here’s a fun look at the Hollywood trope of swordplay in the rigging.

We can probably blame Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island for the trope’s ultimate inspiration. In the novel [Spoiler Alert!], Jim Hawkins climbs aloft aboard the schooner Hispaniola to escape the murderous pirate Israel Hands, ultimately burning the salty thug’s brains with a brace of pistols. Why the hungover, perhaps even still-besotted, sea-thief didn’t simply use a musket to murder the lad is unknown. Perhaps he was too fogged by rum to think of it, or he didn’t have a musket at hand, or knew he wouldn’t be able to hit the bold lad. More likely, it’s simply a much better scene to have a murderous pirate armed with a knife slowly climb aloft while his victim waits at the extreme point of retreat.

“One Step More, Mr. Hands” by N. C. Wyeth for the 1911 Charles Scribner’s Sons edition of Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson.

Doubtless inspired by Treasure Island, Charles Boardman Hawes includes a scene of fighting aloft in his Newberry award-winnning novel, The Dark Frigate.

But the primary origin of the trope, whether for Mr. Stevenson or Hollywood in general, is almost certainly the simple fact that the masts and rigging are too enticing not be used: a vast network or “jungle gym” overhead with boundless possibilities. It’s simply impossible to ignore the setting towering aloft above a vessel’s decks. It’s a nautical gymnasium begging to be used! And so it often has.

Before going further, we should quickly examine what sailors did, and still do, aloft. They set, take in, and furl sail. They hoist spars and masts aloft, and strike the same as necessary. They stand lookout. They man the tops in battle, enabling armed seamen to fire on the enemy below. They make repairs. They skylark.

Although fighting aloft was routine–men firing from above at men below–there’s no evidence of anything other than with firearms, grenades, and sometimes swivel guns occasionally fired at the enemy also aloft. No swordplay on yards, in other words. Note that in the painting below, no one aloft is wielding a sword, nor are there lines rigged from which to slide down or swing across (another popular but false Hollywood pirate trope). However, note the third image below in which two seamen slide down a forestay.

Actual fighting aloft would look something like this:

The painting just above, although it has many accurate details (including the grappling hook hanging by chain from the yardarm (although it should have two lines attached), appears to be rather romanticized, with seamen sliding down a forestay, another with his cutlass between his teeth, apparently having just slid down the stay, details lacking in the previous two images. Doubtless seamen did slide down stays during routine operations, but during action?

Moving on to film, the earliest scenes of swordplay aloft I’m aware of are those in the 1924 silent version of Peter Pan: a brave Michael — played by Phillipe de Lacy, six or seven years old! — climbs the shrouds after a pirate. The entire melee of lost boys, John, and Michael versus pirates is extraordinarily well-choreographed, far superior to the hack and slash knife sharpening melees of most pirate films, even those with well-choreographed duels between hero and villain. The quality here is no surprise: Henri Uyttenhove was the fencing master and choreographer. The children’s fencing and enthusiasm is a joy to watch.

Even so, when it comes to film, The Black Pirate (Vitagraph, 1926) starring Douglas Fairbanks set the standard for action aloft–but not for swordplay aloft, of which it alas had none. The film included circus-like aerial stunts and a famous scene in which Fairbanks slips a sword or dagger into a sail and slides down its face, cutting the canvas as he does. The stunt was repeated in Against All Flags (Universal-International, 1952), The Goonies (Warner Bros., 1985), Peter Pan (2003 & 2023) and Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (Disney, 2006), although in the the last film it appears heavily CGI’d, and may have been in the 2023 Peter Pan as well.

In Captain Blood (Warner Bros., 1935) starring Errol Flynn, the action aloft is more mundane, although it does include some brief swordplay, and includes a lesser trope: pirates sliding down on ropes during boarding actions, swinging from ship to ship, and occasionally from yard to yard, none of which actually occurred to ship to ship combat. Still, it’s fun.

In Double Crossbones, a 1951 Universal International Pictures pirate comedy starring Donald O’Connor (and from which Disney borrowed some scenes and character development for its pirate franchise), O’Connor as pirate Danny Crandall duels aloft with John Emery as Governor Elden of Charleston, South Carolina. At one point, Hope Emerson as Mistress Anne Bonney hoists him aloft a few times, almost Peter Pan-fashion) to avoid the governor’s cuts and thrusts. One wonders if this inspired Disney’s dueling aloft in its 1953 Peter Pan (see below), although the trope is an obvious one. Even so, I’ve yet to find an illustration of Peter Pan and Captain Hook dueling aloft prior to the 1953 film.

In the end, the governor falls off the yard into the sea; good guy Danny Crandall, who spends much time in the film fencing with broomsticks and candlesticks, is allowed to avoid running his enemy through. Several scenes in the film, and Crandall’s character as well, inspired scenes in Disney’s The Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl.

Notably, John Emery starred as one of the villains in The Spanish Main (1945). In the finale he falls to the sword of Paul Henreid as Captain Nicolas Van Horn, even though Emery was the far superior fencer (although when he first picked up a sword in The Corsican Brothers he knew little if anything — clearly Fred Cavens taught him well). Basil Rathbone could commiserate.

In Against All Flags (Universal International, 1952) Errol Flynn as Brian Hawke climbs aloft via the lubber’s hole (for shame!) to cut down the main-yard. He’s lucky the pirates were lazy, otherwise the yard would’ve been slung with chain in time of battle and his rapier of little use in cutting through. When he sees pirates coming at him from aloft and alow, rather than fight them he escapes instead, using Douglas Fairbanks’s famous technique. The film was remade, almost scene for scene, as The King’s Pirate (Universal, 1967), but an acrobatic escape was substituted for the sword-in-sail trick. Against All Flags was one of Flynn’s last films, certainly one of his last good ones (arguably a tie among these last films with Crossed Swords, The Master of Ballantrae, and a more serious film, The Warriors). Against All Flags also starred Maureen O’Hara in her last swashbuckler. She’s as dashing as Flynn in the film, and as good if not better with a sword.

The Crimson Pirate (Warner Bros., 1952) showcased Burt Lancaster’s acrobatic skills aloft, but lacked swordplay. That said, the antics aloft in the finale are real, not CGI’d, and far more spectacular than anything done before or after, arguably superior even to the gymnastics of Douglas Fairbanks in The Black Pirate:

Disney’s Peter Pan (1953) had plenty of action aloft, including an homage to Treasure Island:

But the real action was between Pan and Hook on the main-topsail yard:

And also in Return to Neverland (Disney, 2002):

The action is included on the Disney theme park attraction:

And even in the Disney theme parks Fantasmic! show:

The trope also made it into a series of Dominica Peter Pan postage stamps in 1980, shown below as a Disney pin:

Hallmark has even introduced (July 2023) a 70th anniversary ornament with Pan and Hook swordplay aloft!

Peter Pan (2003) even included a brief homage to the slide down a sail by cutting it. Here, Hook uses his hook to do the deed. Nearly all of the swordplay aloft was literally in the air, given that Hook was permitted to fly in this version, at least in the finale.

Disney added the same classic pirate trope to its 2023 live action, and rather disappointing, at least in script, sets, and settings, version of Peter and Wendy. A cool move, but unnecessary, as above, given that Peter can fly — unless he’s briefly lost his ability to do so.

The Goonies (1995) reprised the sliding down the sail with cutlass or dagger stunt, first on a television in a scene created on set and added ostensibly to Captain Blood watched by Sloth, then near the end of the film when Sloth slides to the deck of the Inferno, Chunk on his back. In the recent Lego build of The Goonies, which includes ship and major scenes, the sliding down the sail scene is recreated.

But it was Cutthroat Island (Carolco, 1995) that did it’s best to include a sword fight in earnest on a yard aloft. The film was a box office bomb. Even so, Geena Davis did a creditable job, the soundtrack is excellent, and it has earned a deserved cult status as a guilty pleasure, so much so that a 4K release is available.

Even Shaggy and Scooby Doo got into the action aloft in Scooby Doo! Pirates Ahoy! in 2006.

Not to be beat by previous adventure aloft, and surely as an homage too, Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (2007) included swordplay between Davy Jones and Jack Sparrow on a yard aloft during a storm while dueling ships were whipped around at the edge of a giant maelstrom:

Tales of Monkey Island (2009), a five chapter sequel to the previous Monkey Island games, includes swordplay aloft during the opening puzzle of Chapter 2.

The Adventures of Tintin (Columbia Pictures et al, 2011) featured animated if improbable-but-exciting swordplay aloft:

Swordplay, or at least swords, aloft has continued in recent pirate films. Below is Son Ye-jin as Captain Yeo-wol in The Pirates (Harimao Pictures, 2014), engaging in aerial swashbuckling.

The trope made its way even into the recent Thugs of Hindostan (Latina Pictures, et al, 2018), a pirate-ish, Bollywood, stick-it-to-the-English Indian film:

Action aloft also made its way onto television in the form of the final episode in season four of Black Sails, in a scene in which I, as historical consultant, not to mention as a swordsman of nearly fifty years and a fencing teacher for nearly thirty, had some input.

But the trope has found its way into more than just film. A significant but largely unstudied contribution to pirate culture is that of various collector’s cards: tobacco, bubble gun, and arcade. Typically inspired by popular illustration, film, and general cliché, the cards often include images of swordplay and other fighting aloft, invariably via contrived circumstances often involving pirates or merchant seamen attempting to escape aloft. In the 1930s card just below, failed mutineer-pirates retreat aloft to little avail.

Below, in a 1930s Holloway Pirate Treasure trading card, merchant seamen flee aloft to make their last stand, again to no avail.

Below, a Swedish/French bubble gum card dating to the 1930s. This time it’s not a merchant seaman retreating aloft, but a duel over the plunder on a night “full of stars, the air calm, the sea tranquil.” One of the pirates, Mulrooney, has hidden a brace of pistols in the rigging. He drops his cutlass and climbs aloft, followed by his armed adversary Hawkins. Mulrooney, in most dishonorable fashion–even for a pirate–arms himself with his hidden pistols and shoots Hawkins dead.

Comic books are another significant source of modern pirate culture, and like the cards above they typically reinforce existing tropes. Below, Yellow Beak and Black Pete cross cutlasses (or rather, knife and parrot cutlass) in “Donald Duck Finds Pirate Treasure!” (1942, from an original film concept that was never green-lighted).

Below, the sword fight is on the bowsprit, one man armed with an anachronistic rapier (unless he’s an Iberian or perhaps an Italian under Spanish rule) with quillons in the wrong place, the other armed with an anachronistic “soup ladle” cutlass.

And it’s even made it to a book cover!

And even onto a 1000 piece puzzle!

But just how easy would it be to fence aloft on spars? It wouldn’t be. By way of experiment I’ve attempted footwork on a balance beam, much as in the photograph below but with much less danger. At first it’s not easy to maintain balance and any “fencing” done is best done by way of slow choreographed movements. Put simply, I fell often, more even than the time more than forty years ago a friend and I fenced with sabers at midnight in New Orleans under live oaks on a carpet of acorns (it was a mast year). Still, after a bit of practice one can move conditionally well on a flat beam–but still not sufficiently to prevent a likely fall. A rounded spar would be much more difficult to fence upon.

Aerial fencing, usually on rooftops or on beams or scaffolding attached to them, and usually as stunts or photo opportunities, is not uncommon:

Any real fencing on a beam or spar would obviously quickly result in a fall. Many years ago I saw a fencing high wire act performed at the Ringling Bros & Barnum &Bailey Circus: it was composed of simple, if impressive, choreographed movements, as expected.

In similar fashion, the modern aerial troupe Pirates of the Colombian Caribbean performs a tightrope fencing act on tour, including this past summer at the Miami Seaquarium:

But could swordplay aloft have happened in reality? Even rarely? The answer is akin to that of the myth of buried pirate treasure. Did pirates bury treasure? No, although it’s possible to find a rare instance of a couple of shipwrecked pirates burying their plundered shares to keep other pirates from stealing it. Further, it’s possible to imagine a rare similar but more significant exception, for example the shipwreck of pursued pirates who bury their plunder to prevent a pirate hunting landing party from finding it. But there’s no evidence anything like this ever happened. Similarly, there’s no evidence of swordplay aloft among pirates or anyone else at sea, as thrilling and pregnant with possibility the prospect is. Even so, it’s possible to imagine a rather contrived, but still possible, circumstance. Hollywood does it all the time.

Copyright Benerson Little, 2019-2025. First posted September 18, 2019. Last updated November 27, 2025.