The Pirate Captain & His Burning Prey Upon the Background Billows: An Iconic Image

Arguably only a few illustrators have matched, and none have surpassed, Howard Pyle (1853-1911) for his iconic pirate images and their contribution to the modern myth of pirates and piracy. Whether of picturesque and picaresque buccaneers, or of pirate attacks, duels, buried treasure, or extortion of prisoners, his illustrations, with few exceptions, have inspired imitation and homage.

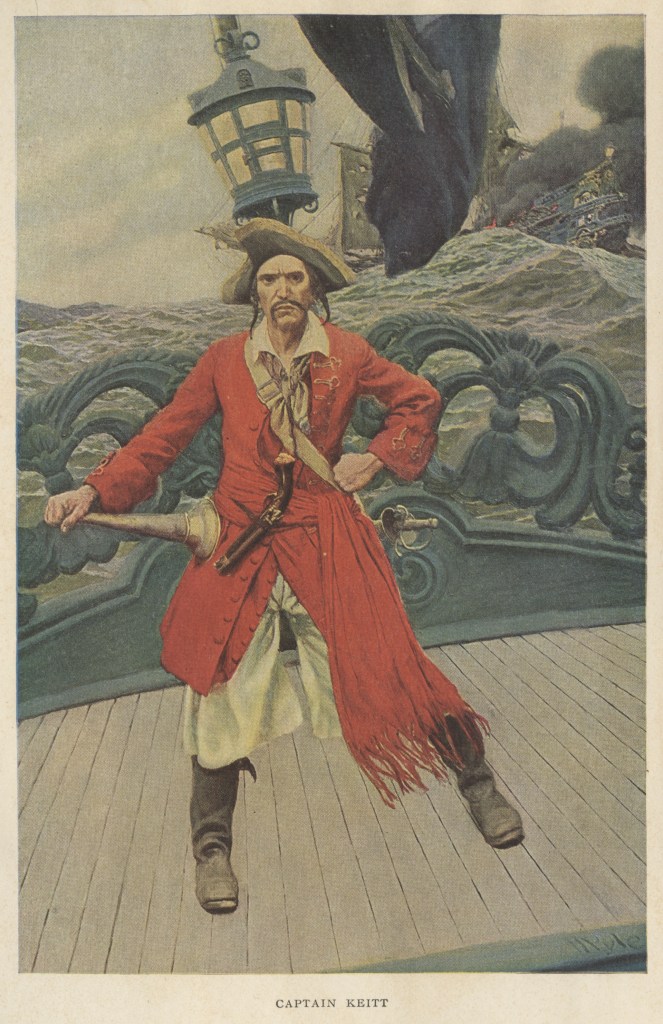

Of all Pyle’s strikingly evocative pirate art, his painting of Captain Keitt for his novella The Ruby of Kishmoor is considered by many to be the pinnacle of his work. We see it above: the pirate captain, clearly inspired by Captain Kidd, braced seaman-fashion on the poop of his pirate ship The Good Fortune in the trough of the sea, his prey, the Rajah of Kishmoor’s great ship The Sun of the East, burning in the background upon the crest of a swell, its mainsail shot to pieces.

The ship’s lantern rises behind the pirate captain, and curiously — and surely for reasons or artistic composition — behind it the ensign staff flying the Jolly Roger. I quibble here: the lantern would historically have been astern of the flagstaff, outboard of the hull, the other inboard. Curiously, the lanterns, and in fact the stern decoration and color, of both ships appear similar if not identical (and somewhat similar ones can also be seen on Disney’s pirate ship the Black Pearl).

Keitt wears an 18th century style cocked hat (aka tricorn) with gold trim, setting off his rather ratty black hair and long mustachios framing a stern face that hints of evil, an expression suggesting he might be posing for a painter, recalling perhaps the pirate portraits in Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America. Or perhaps he has been caught off guard, or has been asked a stupid question.

A ratty kerchief is tied around his neck rather than a cravat, and he wears a crimson just-au-corps, waistcoat, and long swashbuckling sash. His wide loose breeches are the seaman’s, and on his feet he wears boots of some sort, perhaps intended as “sea boots” although such were worn largely by fishermen and by seamen of this era only in cold weather. The boots are a deliberate cliché or trope: even more than a century ago the audience expected to see pirates in boots, though most often of those for riding with tops folded over. Pirates wore shoes and stockings or, especially if poor, went barefooted. The idea of “pirate boots” derives via popular illustrators from those of cavaliers and musketeers.

Hanging from a buff baldric is a Spanish “bilbo” style rapier with large curved shells although he would likely have worn a cutlass instead, and from a waist-belt. A short-barreled pistol is stuffed into the sash, and Keitt holds a speaking trumpet in his hand, perhaps with which to verbally abuse those victims doubtless left behind on the burning, sinking ship — he surely no longer has any need of the trumpet for hailing. Perhaps he uses it to bellow at his crew rather than pass orders via his subordinate officers.

There is a somber aspect to the painting: those aboard The Sun of the East who did not perish in the battle and boarding action have surely been left to the severe mercy of the sea.

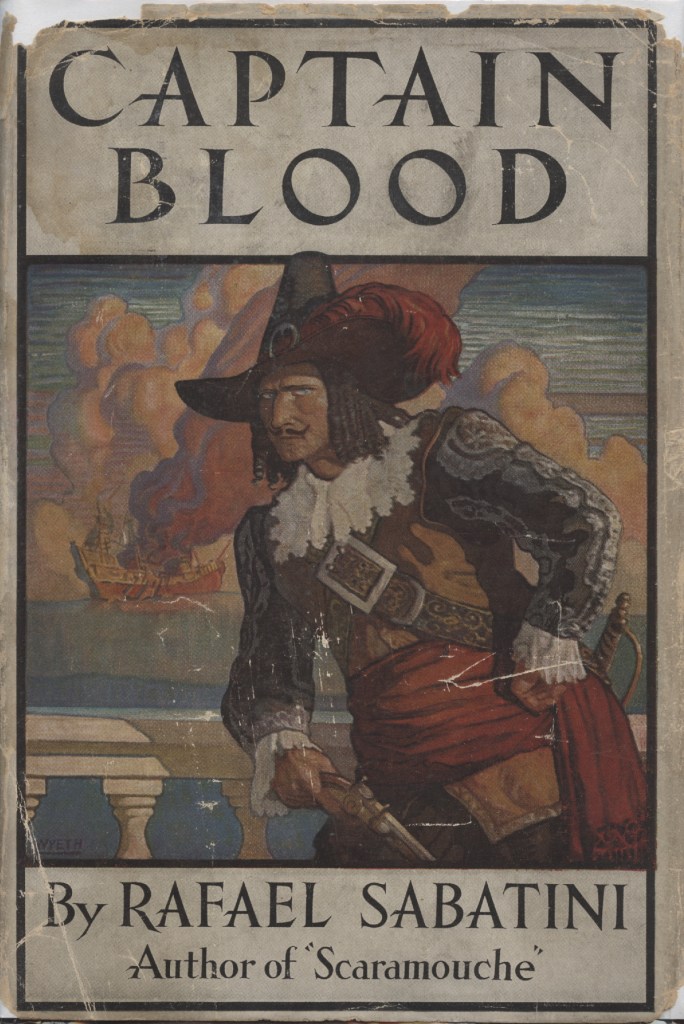

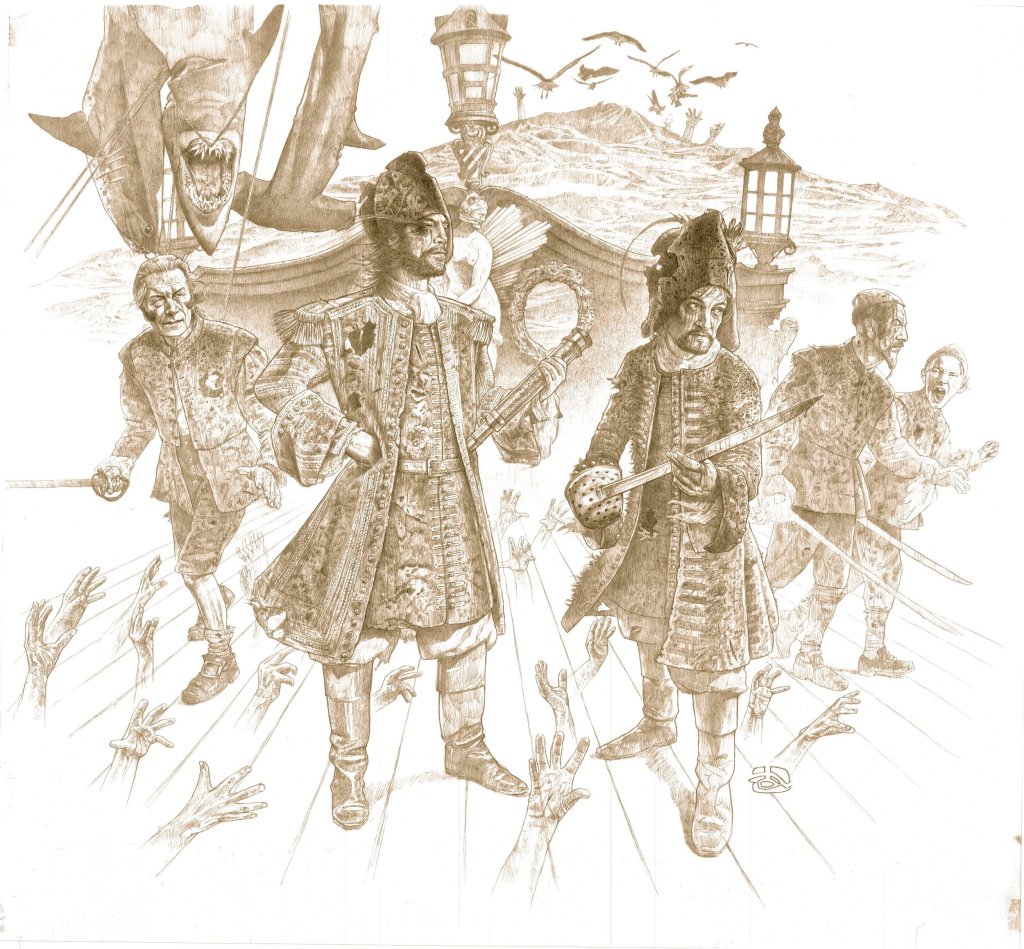

N. C. Wyeth’s frontispiece and dust jacket art for the US edition of Rafael Sabatini’s Captain Blood: His Odyssey (1922) is almost as famous as Pyle’s painting. Clearly an homage to his teacher’s famous painting, Wyeth’s work embraces the image of Sabatini’s eponymous hero, even if he depicts the famous literary buccaneer in more mid-17th century style rather than of the 1680s. It’s not entirely Wyeth’s fault. Foremost, he intends to evoke the novel and its hero, rather than portray them with complete historical accuracy. Further, Sabatini himself occasionally misuses terms for period dress, for example writing doublet when clearly he intends the just-au-corps, the long coat worn in the 1680s and after.

Still, Wyeth’s painting is true enough to the novel, and clearly he had read it. The illustration was first painted then later used for a novel because it was close enough, as with Wyeth’s dust jacket art and frontispiece for The Black Swan. In the painting above, Peter Blood’s hair and eyes are accurately presented — black and blue — and he has a small mustache as he did in the serialized novel but which he had lost when the novel was published.

He wears a doublet with silver-laced black sleeves, although this ought to be a black and silver just-au-corps. He wears a falling collar of Mechlin lace rather than a cravat of one, and a bullion-encrusted baldric. His hat is rather tall for the period but has the required crimson ostrich plume. The crimson feather is there to add color, but all in all Peter Blood’s dress is close enough to Sabatini’s description: “scrupulously dressed in black with silver lace, a crimson ostrich plume curled about the broad brim of his hat affording the only touch of colour.”

We can easily forgive Wyeth our quibbling criticisms, for, to repeat ourselves, the painting is intended to be figurative and evocative. It is, to quote a past editor of mine in regard to book illustrations, intended to entice potential readers to buy the book.

In the background a Spanish galleon burns, clearly an abandoned prize, although the burning of prizes, but for an English man-of-war (with a Dutch admiral, curiously) burned by the French, is not mentioned in the novel. Perhaps the image is of the Spanish fleet’s flagship Milagrosa which was to be “scuttled” after being defeated by Blood’s buccaneers. More likely, it is a generic image of one of the unnamed Spanish galleons captured by Captain Blood.

In practice burning was often easier than scuttling, particular with larger ships. Buccaneers did occasionally burn prizes, typically keeping some crew and passengers as prisoners while turning the rest loose in a boat, and occasionally sank smaller prizes as well. More often though they were likely to keep the prize or leave it with its crew and passengers, first cutting a mast down or taking some of its sails so that word of the buccaneers might not be swiftly carried to the nearest port.

Of note are the orange-gold clouds with red-black plumes of smoke in front. A sun, perhaps, setting on the galleon and Spanish Empire? Gold for plunder, and red-black for the two colors Sabatini repeatedly uses as themes in the novel?

From the 1927 et al Riverside Press Cambridge (a Houghton Mifflin imprint) edition of Captain Blood: His Odyssey, the dust jacket and front cover art by Clyde Osmer Deland (1872-1947). Although the painting is more historically accurate — no boots, correct just-au-corps and hat — it lacks the eye-catching flair of an illustration by Pyle or Wyeth, even if a burning sinking ship draws the eye. And again there’s that damned mustache that’s not in the novel! Here, Deland has no excuse, given that he painted the illustrations several years after the novel’s publication.

The ship is not burning in the illustration above, but the magazine cover was clearly inspired by Pyle and Wyeth’s paintings. The pirate depiction, in particular its resemblance to the much later Captain Jack Sparrow, is discussed here.

Another Wyeth painting hinting at an homage to his teacher Howard Pyle and which has influenced our idea of the pirate captain and his burning prey on the billows. The blue-green tropical sea is up, giving us the mountain-like billows we like to see — and which also aid in composition. The burning ship is clearly a Spanish galleon, of a style much-used by Wyeth and discussed here. That it has just been plundered is obvious: booty is piled on the poop, including a classic Pyle-style treasure chest with curved top. The buccaneer captain is almost identical to one Wyeth painted for the September 22, 1921 issue of Wall Street Number magazine, a Life magazine publication, discussed here.

The galleon rests on a crest, with the buccaneer ship below in the trough, suggesting the rover is sailing away. Classic Wyeth clouds frame the galleon, and the skull and bones — an anachronism — flies at the stern but we can see only the lower part of the field, as in Pyle’s painting at the top of the page, clearly an homage.

Yet another homage, this time Peter Hurd (1904-1984) to his teacher N. C. Wyeth. Although Hurd was best-known for his paintings and illustrations of life in the Southwest US, he edited and illustrated Marauders of the Sea, a collection of excerpts from pirate stories, 1935, with an introduction by N. C. Wyeth. In the painting, two ships are closely engaged, one of them afire. Here, the pirate captain is not standing the deck of his ship. Rather, the composition is clearly arranged after late 17th century paintings and illustrations of pirate and men-of-war captains and admirals, as will be discussed in more detail shortly.

Hurd’s pirate captain reminds us of the famous depictions of Exquemelin’s buccaneers shown farther below. His eyes are blue and his hair black, like Peter Blood’s, but he also has a Spanish-style mustache and a scar across his cheek. He wields a classic shell-hilt cutlass with large brass rather than iron shells, though all the large shells I’ve seen on cutlasses were iron — only smaller shells might be made of brass. His face is scarred, his jacket is either Spanish or an earlier English doublet, and he wears breast and backplate which Peter Blood did fictitiously and some captains of men-of-war did in reality. Whether any buccaneer captains actually did is entirely speculative, for there is no record of them doing so.

Other Notable Homages

I’ve chosen one authorized imitation of Wyeth’s “Captain Blood,” one authorized inspiration of the Pyle/Wyeth paintings, and also several notable homages, five of them to Howard Pyle’s “famous painting at the top” Captain Keitt,” and rest to Pyle and perhaps to Wyeth and others as well — an homage to homages and to the original.

Three illustrations by George Alfred Williams, the first from The Boy’s Book of Pirates and the Sea Rovers by George Alfred Williams (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1913). It is a likely homage to Pyle’s painting — and only five years afterward. The second and third are from The Pirates of Panama or The Buccaneers of America by John Esquemeling (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1914). Both are clearly homages to Pyle’s famous painting. All three doubtless contributed to the image of the iconic image of the pirate captain and his burning ship on the background billows.

The first image of the four just above is the front cover of the program for the 1924 film version of Captain Blood (Vitagraph) at Astor Theatre, Broadway and 45th, in New York City. The image was also used on a poster for the film. The cover style has been copied from a combination of the dust jacket of the 1922 US release of the novel and of the front board of the book. I’m no fan: here Captain Blood looks more like an unadventurous bourgeois dressed as a pirate for a costume party, rather than the long, lean, hawk-faced adventurer-physician-buccaneer described in the novel.

The likeness is intended to represent J. Warren Kerrigan who played the starring role. Perhaps the unknown illustrator was getting a dig in at Kerrigan and felt the same way I do about him. The actor famously told The Denver Times during the First World War that “I am not going to war. I will go, of course, if my country needs me, but I think that first they should take the great mass of men who aren’t good for anything else, or are only good for the lower grades of work.” Clearly he was no Sabatini-esque hero in real life, nor even an Errol Flynn, at least in regard to courage, panache, dignity, and empathy.

The bottom image is a copy of one of the many posters designed for the 1924 film, clearly inspired by both Pyle and Wyeth. Atypically, the ship is exploding rather than simply burning, although the latter often led to the former.

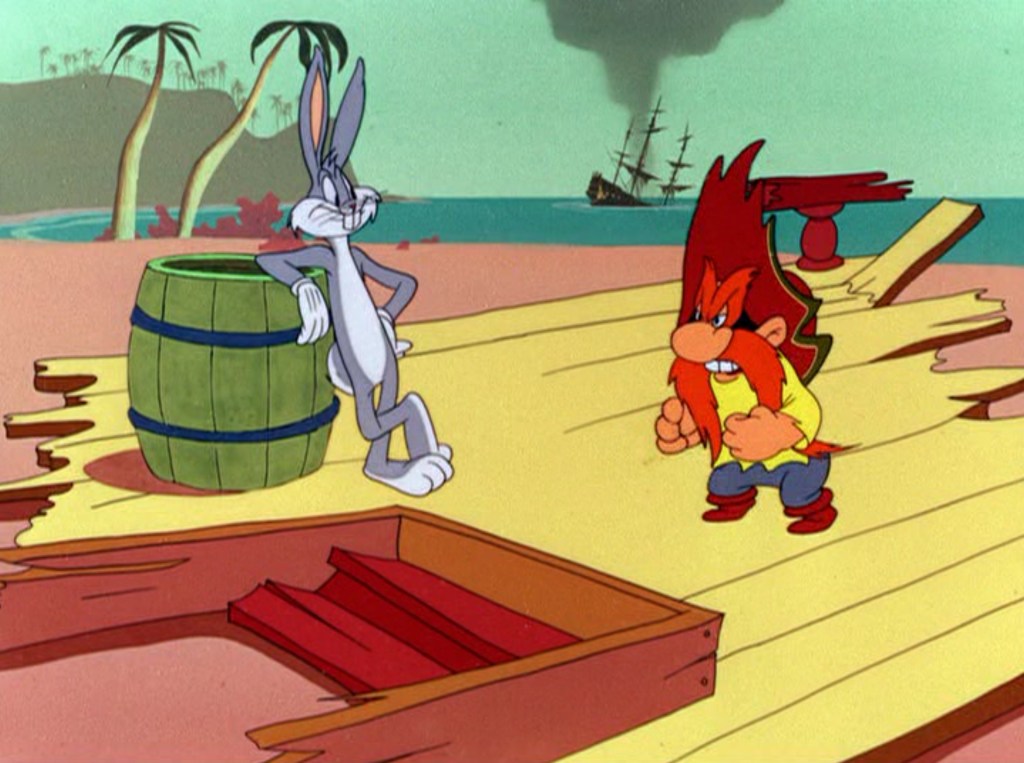

The writers and artists of “Buccaneer Bunny” (Warner Bros. Looney Tunes, 1948) clearly intended an homage to Pyle and Wyeth. It’s basically a reverse or mirror image of the Captain Blood cover art and frontispiece done by N. C. Wyeth. DVD screen capture.

Above is a possible homage to Pyle and Wyeth: Errol Flynn as Brian Hawke just having rescued Alice Kelley as Princess Padma from the burning ship of the Mughal Emperor. Compare with The Goonies screen capture below.

In the painting above there is no burning ship, but one firing a broadside instead. Even so, the image is clearly inspired by the paintings of Pyle and Wyeth, and as much by the illustrations from Alexandre Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America discussed below. The painting, artist unknown but suggested by some to be Ed Kohn, has hung for many years in the Pieces of Eight store adjacent to the Pirates of the Caribbean ride at Disneyland. Originally it hung in the Pirates Arcade Museum (mostly an arcade) before the shop replaced it in 1980. It may depict Fortune Red, the animatronic fortune teller in the arcade.

Above, an homage if you like, and clearly a comic riff, on Pyle’s famous painting. A damsel-in-distress has been added — and Chunk’s tongue too… From the attic scene in The Goonies, 1985. Compare with the Against All Flags screen capture above it.

The Goonies painting as imagined by Lego, part of a kit (“The Goonies: The Walshes’ Attic”) to accompany The Goonies ship and the film scenes depicted inside.

I hesitated to post the image above, of Arnold Schwarzenegger as Captain Blood by William Stout. The film was under consideration in 1994, and, although I have great respect for the former Governor of California as an action hero, I am overjoyed that the film never made it into production. The proposed script was of a sort commonly pitched by studio executives, producers, and screenwriters: one intended solely to make money (art, artist, and audience be damned).

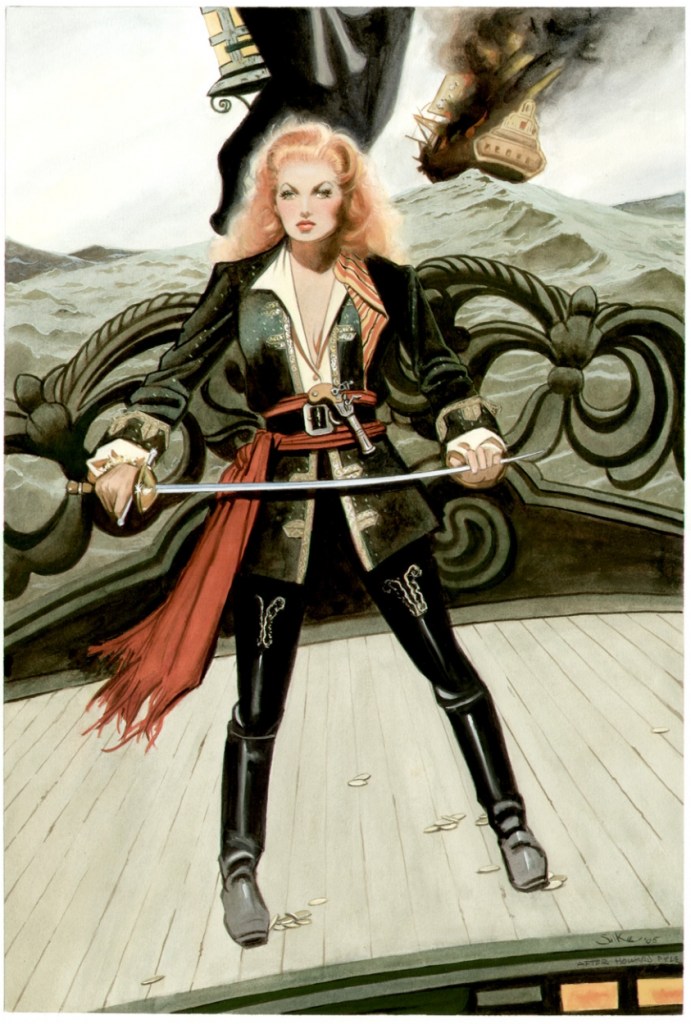

Above is an homage by arts and entertainment polymath Jim (James R.) Silke (1931-present) to Howard Pyle’s famous painting (see “After Howard Pyle” below the signature on the painting above) featuring Maureen O’Hara as Spitfire Stevens in Against All Flags (1952), also starring Errol Flynn. The 2005 work was created as a commission for Brian Peck.

My good friend Antón Viejo Alonso brought the image above to my attention. Drawn by noted portrait artist and film costume concept illustrator Darrell Warner for Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (Disney Studios, 2017), it is clearly an homage to the Howard Pyle painting at the top of the page.

A cropped image from Netflix’s live action 2023 release of One Piece, with pirate-captain-to-be Monkey D. Luffy (played by Iñaki Godoy) in the foreground (foresea? :-)) with a burning ship in the “backsea,” clearly an homage to Pyle, Wyeth, et al. Furthering this argument is the fact that the scene with burning ship is not in the original manga written and illustrated by Eiichiro Oda nor in the anime based on it produced by Toei Animation. (N. B. there is a similar scene when the [Spoiler Alert!] Going Merry burns and sinks much farther along in the voyages of the Straw Hat Pirates, which is perhaps an homage [Spoiler Alert!] to Peter’s Blood’s loss of his beloved Arabella).

Inspirations & Influences

The most likely inspiration — the seed planted in the subconscious — might well be some of the original illustrations in Alexandre Exquemelin’s early Dutch, Spanish, and English editions of The Buccaneers of America. They include several portraits of famous buccaneers, although we have no idea how accurate the depictions are, but this matters little in regard to inspiration.

The three illustrations above are Spanish edition copies of the originals in the Dutch 1678 edition: Francois L’Ollonois, Bartholomew Portuguese, and Henry Morgan. All show battles, including sea fights, raging in the background, with billowing smoke suggesting that some ships may be afire. None of these buccaneer captains — as far as we know — are standing on the the decks of the ships. It took Howard Pyle’s genius to compose a portrait evoking the adventure and romance, at least as we believe it to have been, of piracy on the high seas.

The illustrations in Exquemelin’s books were doubtless inspired by a common form of portraiture associated with fighting seamen and soldiers, officers in particular for typically only they could afford portraits or had enough social status that a patron might commission a portrait of them.

The two portraits above are typical of those of the era: the subject in the foreground, with a depiction of a major associated action in the background. Myngs, prior to becoming an admiral, led a number of raids on the Spanish Main, with buccaneers-as-privateers as his consorts, after the English captured Jamaica from Spain. The portrait of Montague shows us a burning ship, but it may not be that of an enemy. It appears to be of English build, and is therefore more likely the HMS Royal James, Montague’s flagship burned by a Dutch fireship in 1672, resulting in Montague’s death.

Not quite yet a buccaneer or pirate in the photograph above, nor yet a burning ship on the background billows — but aspirations enough. 🙂

Copyright Benerson Little 2024. First posted 24 September 2024. Last updated November 1, 2025.