Home » Posts tagged 'Maureen O’Hara'

Tag Archives: Maureen O’Hara

The Pirate Captain & His Burning Prey Upon the Background Billows: An Iconic Image

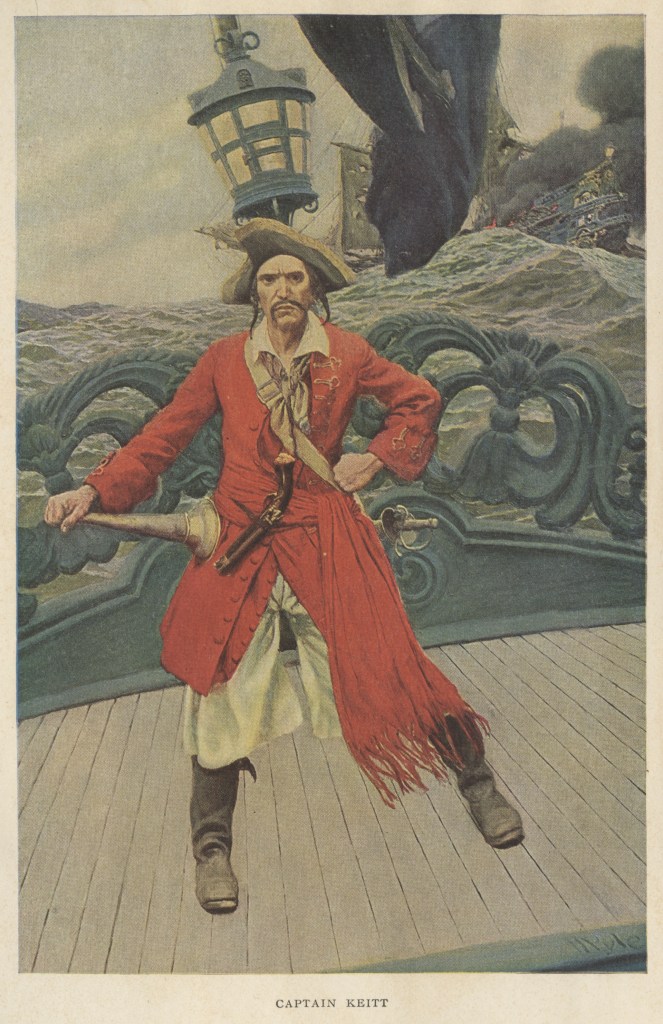

Arguably only a few illustrators have matched, and none have surpassed, Howard Pyle (1853-1911) for his iconic pirate images and their contribution to the modern myth of pirates and piracy. Whether of picturesque and picaresque buccaneers, or of pirate attacks, duels, buried treasure, or extortion of prisoners, his illustrations, with few exceptions, have inspired imitation and homage.

Of all Pyle’s strikingly evocative pirate art, his painting of Captain Keitt for his novella The Ruby of Kishmoor is considered by many to be the pinnacle of his work. We see it above: the pirate captain, clearly inspired by Captain Kidd, braced seaman-fashion on the poop of his pirate ship The Good Fortune in the trough of the sea, his prey, the Rajah of Kishmoor’s great ship The Sun of the East, burning in the background upon the crest of a swell, its mainsail shot to pieces.

The ship’s lantern rises behind the pirate captain, and curiously — and surely for reasons or artistic composition — behind it the ensign staff flying the Jolly Roger. I quibble here: the lantern would historically have been astern of the flagstaff, outboard of the hull, the other inboard. Curiously, the lanterns, and in fact the stern decoration and color, of both ships appear similar if not identical (and somewhat similar ones can also be seen on Disney’s pirate ship the Black Pearl).

Keitt wears an 18th century style cocked hat (aka tricorn) with gold trim, setting off his rather ratty black hair and long mustachios framing a stern face that hints of evil, an expression suggesting he might be posing for a painter, recalling perhaps the pirate portraits in Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America. Or perhaps he has been caught off guard, or has been asked a stupid question.

A ratty kerchief is tied around his neck rather than a cravat, and he wears a crimson just-au-corps, waistcoat, and long swashbuckling sash. His wide loose breeches are the seaman’s, and on his feet he wears boots of some sort, perhaps intended as “sea boots” although such were worn largely by fishermen and by seamen of this era only in cold weather. The boots are a deliberate cliché or trope: even more than a century ago the audience expected to see pirates in boots, though most often of those for riding with tops folded over. Pirates wore shoes and stockings or, especially if poor, went barefooted. The idea of “pirate boots” derives via popular illustrators from those of cavaliers and musketeers.

Hanging from a buff baldric is a Spanish “bilbo” style rapier with large curved shells although he would likely have worn a cutlass instead, and from a waist-belt. A short-barreled pistol is stuffed into the sash, and Keitt holds a speaking trumpet in his hand, perhaps with which to verbally abuse those victims doubtless left behind on the burning, sinking ship — he surely no longer has any need of the trumpet for hailing. Perhaps he uses it to bellow at his crew rather than pass orders via his subordinate officers.

There is a somber aspect to the painting: those aboard The Sun of the East who did not perish in the battle and boarding action have surely been left to the severe mercy of the sea.

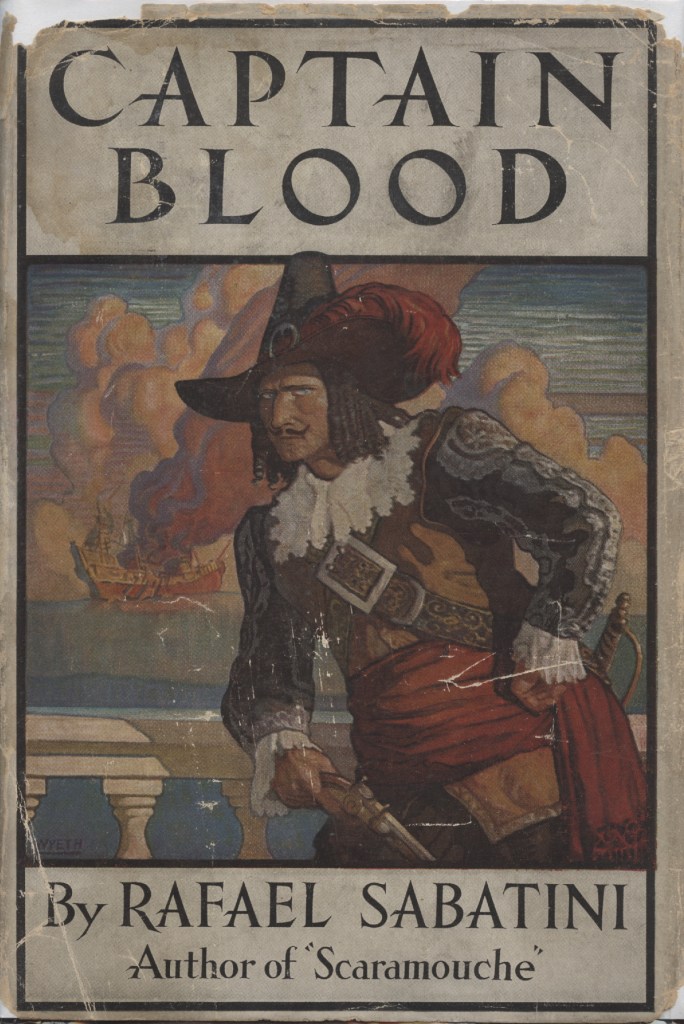

N. C. Wyeth’s frontispiece and dust jacket art for the US edition of Rafael Sabatini’s Captain Blood: His Odyssey (1922) is almost as famous as Pyle’s painting. Clearly an homage to his teacher’s famous painting, Wyeth’s work embraces the image of Sabatini’s eponymous hero, even if he depicts the famous literary buccaneer in more mid-17th century style rather than of the 1680s. It’s not entirely Wyeth’s fault. Foremost, he intends to evoke the novel and its hero, rather than portray them with complete historical accuracy. Further, Sabatini himself occasionally misuses terms for period dress, for example writing doublet when clearly he intends the just-au-corps, the long coat worn in the 1680s and after.

Still, Wyeth’s painting is true enough to the novel, and clearly he had read it. The illustration was first painted then later used for a novel because it was close enough, as with Wyeth’s dust jacket art and frontispiece for The Black Swan. In the painting above, Peter Blood’s hair and eyes are accurately presented — black and blue — and he has a small mustache as he did in the serialized novel but which he had lost when the novel was published.

He wears a doublet with silver-laced black sleeves, although this ought to be a black and silver just-au-corps. He wears a falling collar of Mechlin lace rather than a cravat of one, and a bullion-encrusted baldric. His hat is rather tall for the period but has the required crimson ostrich plume. The crimson feather is there to add color, but all in all Peter Blood’s dress is close enough to Sabatini’s description: “scrupulously dressed in black with silver lace, a crimson ostrich plume curled about the broad brim of his hat affording the only touch of colour.”

We can easily forgive Wyeth our quibbling criticisms, for, to repeat ourselves, the painting is intended to be figurative and evocative. It is, to quote a past editor of mine in regard to book illustrations, intended to entice potential readers to buy the book.

In the background a Spanish galleon burns, clearly an abandoned prize, although the burning of prizes, but for an English man-of-war (with a Dutch admiral, curiously) burned by the French, is not mentioned in the novel. Perhaps the image is of the Spanish fleet’s flagship Milagrosa which was to be “scuttled” after being defeated by Blood’s buccaneers. More likely, it is a generic image of one of the unnamed Spanish galleons captured by Captain Blood.

In practice burning was often easier than scuttling, particular with larger ships. Buccaneers did occasionally burn prizes, typically keeping some crew and passengers as prisoners while turning the rest loose in a boat, and occasionally sank smaller prizes as well. More often though they were likely to keep the prize or leave it with its crew and passengers, first cutting a mast down or taking some of its sails so that word of the buccaneers might not be swiftly carried to the nearest port.

Of note are the orange-gold clouds with red-black plumes of smoke in front. A sun, perhaps, setting on the galleon and Spanish Empire? Gold for plunder, and red-black for the two colors Sabatini repeatedly uses as themes in the novel?

From the 1927 et al Riverside Press Cambridge (a Houghton Mifflin imprint) edition of Captain Blood: His Odyssey, the dust jacket and front cover art by Clyde Osmer Deland (1872-1947). Although the painting is more historically accurate — no boots, correct just-au-corps and hat — it lacks the eye-catching flair of an illustration by Pyle or Wyeth, even if a burning sinking ship draws the eye. And again there’s that damned mustache that’s not in the novel! Here, Deland has no excuse, given that he painted the illustrations several years after the novel’s publication.

The ship is not burning in the illustration above, but the magazine cover was clearly inspired by Pyle and Wyeth’s paintings. The pirate depiction, in particular its resemblance to the much later Captain Jack Sparrow, is discussed here.

Another Wyeth painting hinting at an homage to his teacher Howard Pyle and which has influenced our idea of the pirate captain and his burning prey on the billows. The blue-green tropical sea is up, giving us the mountain-like billows we like to see — and which also aid in composition. The burning ship is clearly a Spanish galleon, of a style much-used by Wyeth and discussed here. That it has just been plundered is obvious: booty is piled on the poop, including a classic Pyle-style treasure chest with curved top. The buccaneer captain is almost identical to one Wyeth painted for the September 22, 1921 issue of Wall Street Number magazine, a Life magazine publication, discussed here.

The galleon rests on a crest, with the buccaneer ship below in the trough, suggesting the rover is sailing away. Classic Wyeth clouds frame the galleon, and the skull and bones — an anachronism — flies at the stern but we can see only the lower part of the field, as in Pyle’s painting at the top of the page, clearly an homage.

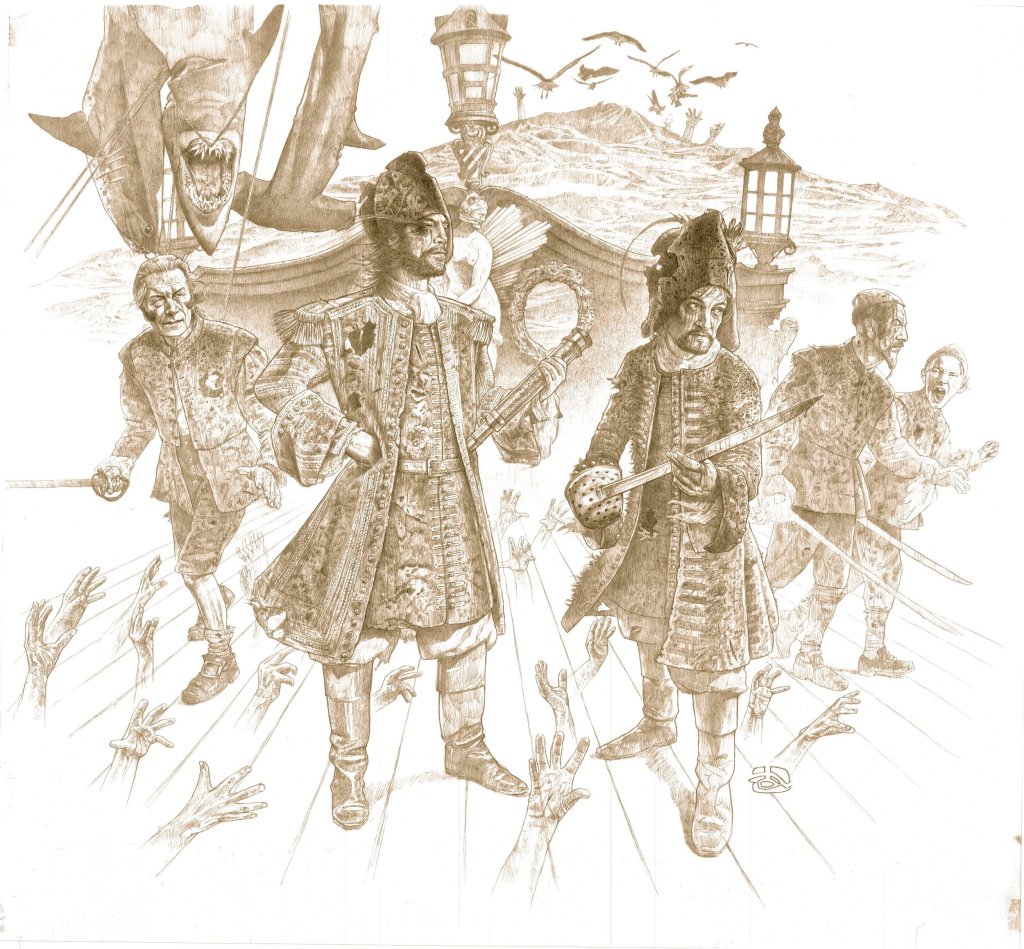

Yet another homage, this time Peter Hurd (1904-1984) to his teacher N. C. Wyeth. Although Hurd was best-known for his paintings and illustrations of life in the Southwest US, he edited and illustrated Marauders of the Sea, a collection of excerpts from pirate stories, 1935, with an introduction by N. C. Wyeth. In the painting, two ships are closely engaged, one of them afire. Here, the pirate captain is not standing the deck of his ship. Rather, the composition is clearly arranged after late 17th century paintings and illustrations of pirate and men-of-war captains and admirals, as will be discussed in more detail shortly.

Hurd’s pirate captain reminds us of the famous depictions of Exquemelin’s buccaneers shown farther below. His eyes are blue and his hair black, like Peter Blood’s, but he also has a Spanish-style mustache and a scar across his cheek. He wields a classic shell-hilt cutlass with large brass rather than iron shells, though all the large shells I’ve seen on cutlasses were iron — only smaller shells might be made of brass. His face is scarred, his jacket is either Spanish or an earlier English doublet, and he wears breast and backplate which Peter Blood did fictitiously and some captains of men-of-war did in reality. Whether any buccaneer captains actually did is entirely speculative, for there is no record of them doing so.

Other Notable Homages

I’ve chosen one authorized imitation of Wyeth’s “Captain Blood,” one authorized inspiration of the Pyle/Wyeth paintings, and also several notable homages, five of them to Howard Pyle’s “famous painting at the top” Captain Keitt,” and rest to Pyle and perhaps to Wyeth and others as well — an homage to homages and to the original.

Three illustrations by George Alfred Williams, the first from The Boy’s Book of Pirates and the Sea Rovers by George Alfred Williams (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1913). It is a likely homage to Pyle’s painting — and only five years afterward. The second and third are from The Pirates of Panama or The Buccaneers of America by John Esquemeling (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1914). Both are clearly homages to Pyle’s famous painting. All three doubtless contributed to the image of the iconic image of the pirate captain and his burning ship on the background billows.

The first image of the four just above is the front cover of the program for the 1924 film version of Captain Blood (Vitagraph) at Astor Theatre, Broadway and 45th, in New York City. The image was also used on a poster for the film. The cover style has been copied from a combination of the dust jacket of the 1922 US release of the novel and of the front board of the book. I’m no fan: here Captain Blood looks more like an unadventurous bourgeois dressed as a pirate for a costume party, rather than the long, lean, hawk-faced adventurer-physician-buccaneer described in the novel.

The likeness is intended to represent J. Warren Kerrigan who played the starring role. Perhaps the unknown illustrator was getting a dig in at Kerrigan and felt the same way I do about him. The actor famously told The Denver Times during the First World War that “I am not going to war. I will go, of course, if my country needs me, but I think that first they should take the great mass of men who aren’t good for anything else, or are only good for the lower grades of work.” Clearly he was no Sabatini-esque hero in real life, nor even an Errol Flynn, at least in regard to courage, panache, dignity, and empathy.

The bottom image is a copy of one of the many posters designed for the 1924 film, clearly inspired by both Pyle and Wyeth. Atypically, the ship is exploding rather than simply burning, although the latter often led to the former.

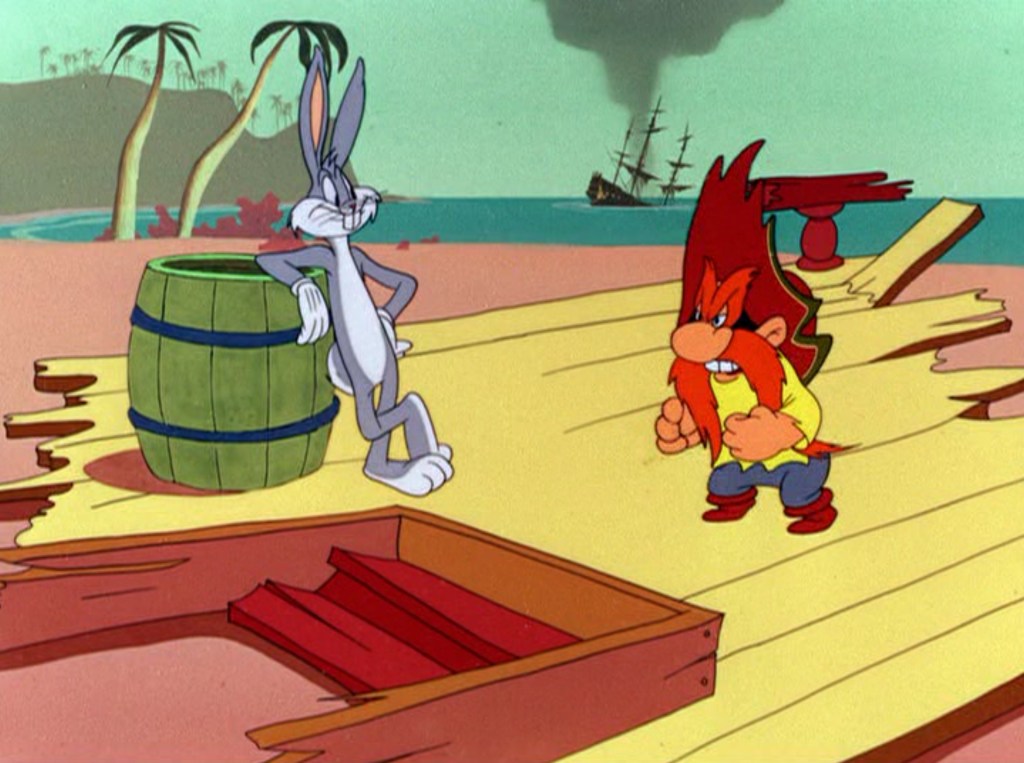

The writers and artists of “Buccaneer Bunny” (Warner Bros. Looney Tunes, 1948) clearly intended an homage to Pyle and Wyeth. It’s basically a reverse or mirror image of the Captain Blood cover art and frontispiece done by N. C. Wyeth. DVD screen capture.

Above is a possible homage to Pyle and Wyeth: Errol Flynn as Brian Hawke just having rescued Alice Kelley as Princess Padma from the burning ship of the Mughal Emperor. Compare with The Goonies screen capture below.

In the painting above there is no burning ship, but one firing a broadside instead. Even so, the image is clearly inspired by the paintings of Pyle and Wyeth, and as much by the illustrations from Alexandre Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America discussed below. The painting, artist unknown but suggested by some to be Ed Kohn, has hung for many years in the Pieces of Eight store adjacent to the Pirates of the Caribbean ride at Disneyland. Originally it hung in the Pirates Arcade Museum (mostly an arcade) before the shop replaced it in 1980. It may depict Fortune Red, the animatronic fortune teller in the arcade.

Above, an homage if you like, and clearly a comic riff, on Pyle’s famous painting. A damsel-in-distress has been added — and Chunk’s tongue too… From the attic scene in The Goonies, 1985. Compare with the Against All Flags screen capture above it.

The Goonies painting as imagined by Lego, part of a kit (“The Goonies: The Walshes’ Attic”) to accompany The Goonies ship and the film scenes depicted inside.

I hesitated to post the image above, of Arnold Schwarzenegger as Captain Blood by William Stout. The film was under consideration in 1994, and, although I have great respect for the former Governor of California as an action hero, I am overjoyed that the film never made it into production. The proposed script was of a sort commonly pitched by studio executives, producers, and screenwriters: one intended solely to make money (art, artist, and audience be damned).

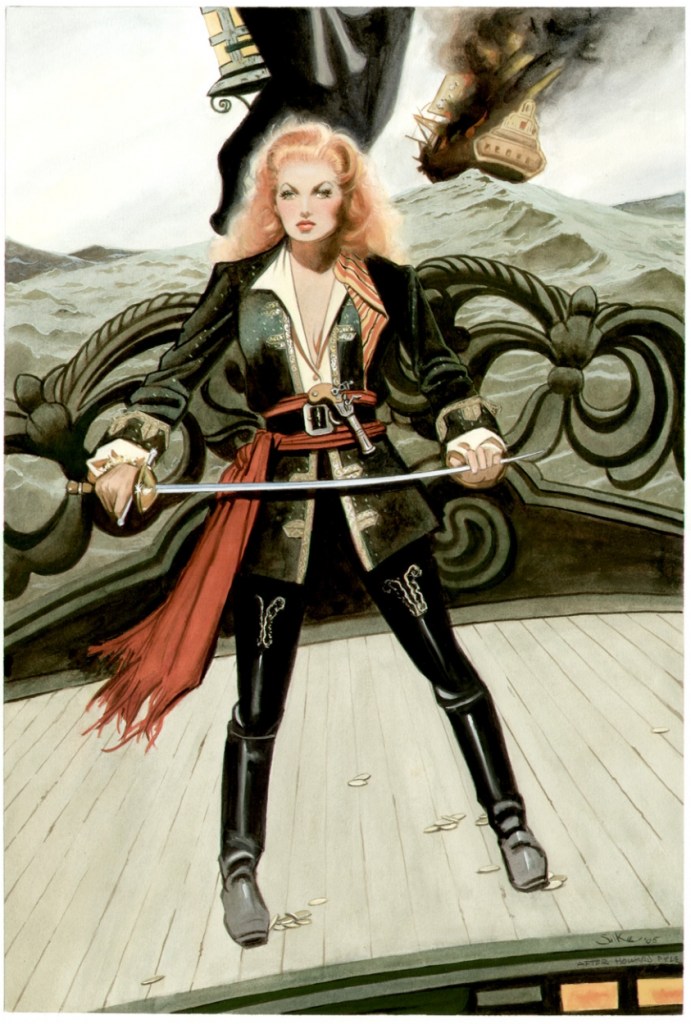

Above is an homage by arts and entertainment polymath Jim (James R.) Silke (1931-present) to Howard Pyle’s famous painting (see “After Howard Pyle” below the signature on the painting above) featuring Maureen O’Hara as Spitfire Stevens in Against All Flags (1952), also starring Errol Flynn. The 2005 work was created as a commission for Brian Peck.

My good friend Antón Viejo Alonso brought the image above to my attention. Drawn by noted portrait artist and film costume concept illustrator Darrell Warner for Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (Disney Studios, 2017), it is clearly an homage to the Howard Pyle painting at the top of the page.

A cropped image from Netflix’s live action 2023 release of One Piece, with pirate-captain-to-be Monkey D. Luffy (played by Iñaki Godoy) in the foreground (foresea? :-)) with a burning ship in the “backsea,” clearly an homage to Pyle, Wyeth, et al. Furthering this argument is the fact that the scene with burning ship is not in the original manga written and illustrated by Eiichiro Oda nor in the anime based on it produced by Toei Animation. (N. B. there is a similar scene when the [Spoiler Alert!] Going Merry burns and sinks much farther along in the voyages of the Straw Hat Pirates, which is perhaps an homage [Spoiler Alert!] to Peter’s Blood’s loss of his beloved Arabella).

Inspirations & Influences

The most likely inspiration — the seed planted in the subconscious — might well be some of the original illustrations in Alexandre Exquemelin’s early Dutch, Spanish, and English editions of The Buccaneers of America. They include several portraits of famous buccaneers, although we have no idea how accurate the depictions are, but this matters little in regard to inspiration.

The three illustrations above are Spanish edition copies of the originals in the Dutch 1678 edition: Francois L’Ollonois, Bartholomew Portuguese, and Henry Morgan. All show battles, including sea fights, raging in the background, with billowing smoke suggesting that some ships may be afire. None of these buccaneer captains — as far as we know — are standing on the the decks of the ships. It took Howard Pyle’s genius to compose a portrait evoking the adventure and romance, at least as we believe it to have been, of piracy on the high seas.

The illustrations in Exquemelin’s books were doubtless inspired by a common form of portraiture associated with fighting seamen and soldiers, officers in particular for typically only they could afford portraits or had enough social status that a patron might commission a portrait of them.

The two portraits above are typical of those of the era: the subject in the foreground, with a depiction of a major associated action in the background. Myngs, prior to becoming an admiral, led a number of raids on the Spanish Main, with buccaneers-as-privateers as his consorts, after the English captured Jamaica from Spain. The portrait of Montague shows us a burning ship, but it may not be that of an enemy. It appears to be of English build, and is therefore more likely the HMS Royal James, Montague’s flagship burned by a Dutch fireship in 1672, resulting in Montague’s death.

Not quite yet a buccaneer or pirate in the photograph above, nor yet a burning ship on the background billows — but aspirations enough. 🙂

Copyright Benerson Little 2024. First posted 24 September 2024. Last updated November 1, 2025.

The Women in Red: The Evolution of a Pirate Trope

With news that Disney is planning a new standalone pirate film starring a female pirate, it’s time review what has become a pirate trope: the woman in red, specifically, or at least often, a redhead. Why this trope in regard to a new Disney film? Because speculation has it that the film will be tied to Redd the Pirate above.

UPDATE: According to Margot Robbie in the press on November 14, 2022, Disney has killed the project, although rumors periodically surface that Disney continues to look at continuing the franchise, including a film with a female protagonist. A pity indeed that the rumored Robbie film was cancelled, it might’ve been quite the film. Certainly the genre needs a new female-led pirate film hearkening back to the Golden Age of Piracy and Pirate Film. There have been only a few made. Shout-out to The Pirates (2014), a Korean comedy-drama about Korean pirates, with strong overtones of the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, starring Son Ye-jin. (And please let it not be about Anne Bonny! See below…)

LATEST UPDATE! As of February 17, 2026, Margot Robbie is reportedly still in talks regarding Pirate of the Caribbean 6. We’ll see…

In the meantime while waiting for a new pirate film with a female lead, we’ll take a quick look at some of the myths and realities of female pirates during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy in the Americas from roughly 1655 to 1730.

The obvious apparent origin of the woman in red (a “scarlet woman”?), at least in terms of pirate fiction and film, is the Redhead in line in the bride auction–“Take a Wench for a Bride”–in the original version of the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean attraction in which drunken pirates shouted, “We wants the redhead!” Forced marriage, in other words, and all of its associated crimes.

Notably, text on the back of the publicity still describes the scene as an auction: “Gold-hungry pirate captain puts the town’s fair maidens–and the ones not so fair–on the auction block for his rowdy crewmen.” Thankfully, things have somewhat changed since then, tongue-in-cheek humor or not.

The Disney auction scene was doubtless inspired by scenes in The Black Swan (1942), Anne of the Indies (1951), and, in particular, Against All Flags (1952), in which captured women are portrayed as captives to be sold or given away as plunder. Both Anne of the Indies and Against All Flags have auction scenes of female captives, and the latter has an auctioneer with whip-in-hand as in the Disney attraction.

When it first opened in 1967, the Disney attraction was intended as–and in fact was–a tongue-in-cheek, lighthearted, swashbuckling film-based version of buccaneers sacking a hapless Spanish town in the Caribbean. Marketing text associated with early publicity stills noted that the ride was a “thoroughly realistic re-creation of buccaneer days.”

To enjoy the ride–which I did and still do–requires viewing it as a fantasy rather than a depiction of reality, for the reality of buccaneer attacks in the seventeenth century was anything but romantic to the victims: torture, rape, murder, and the enslavement of free men, women, and children were common. Documentary evidence of what today would likely be defined as resulting PTSD, among both victim and perpetrator, exists.

Like most of our fictional and cinematic adventure, we tend to sanitize or ignore facts in order to help create a fantasy more amenable to entertainment. Humans have done this for millennia. And there’s often nothing wrong with this unless we confuse the fantasy with the reality, which unfortunately happens all too often.

Today, the ride has been modified somewhat to both fit with the Disney pirate films, which are only loosely inspired by the attraction, and to bring the attraction up-to-date with current social mores. The latter changes have generally been a good thing, I think, even if the changes are not historical (and a few I disagree with). The attraction is a swashbuckling fantasy, after all, not an accurate “Audio-Animatronic” documentary. I’m much less enamored of the changes in keeping with the film franchise.

The most significant of the changing mores alterations to the attraction was the conversion of the pirates-chasing-women scene into one of pirates-chasing-food, and the conversion in 2018 of the bride auction scene into one of conquered residents bearing possessions, perhaps as ransom, and of the famous red-dressed redhead showing a leg into a red-dressed redheaded female pirate standing guard (and still, after a fashion, showing a leg).

Personally, I prefer the new scene and new redhead, ancient passing pre-adolescent fantasies notwithstanding.

In general, as in the original trope-setting (and great fun to watch) pirate swashbuckler, The Black Pirate (1926), leading women in pirate films are usually depicted as the “tavern wench” or “exotic wench,” or other saucy secondary love interest; or the “swooning heroine;” or the “pirate woman.”

The “pirate woman” is usually by far the most interesting, although too often she, Hollywood-style, gives up piracy at the end of the film in exchange for true love. Or she dies in battle, her true love unrequited, her true love interest running off with the “good girl”–often the swooning heroine. At least Against All Flags with Maureen O’Hara and Cutthroat Island with Geena Davis avoided this trope.

Sometimes the tropes are combined: Elizabeth Swann in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl goes from a nod at the literally swooning–via an over-tightened corset (“stays” to be correct)–heroine to pirate woman.

She also wears a red dress in the first film of the series, in scenes which combine multiple tropes: woman in peril, woman tied-up, woman with (airbrushed via CGI, reportedly) cleavage. The dress is a likely homage to the Disney attraction. A red dress also shows up on Scarlett, a tavern wench aka prostitute.

The red dress shows up in other pirate films as well, and as apparent copies or homages in Halloween costumes and video games.

Geena Davis stars in Cutthroat Island (1995, Carolco), and in one scene swashbuckles her way tolerably well with an anachronistic rapier and dressed in a red dress borrowed from a prostitute. The dress is clearly a nod, perhaps more than a bit humorous, at the Disney ride. In fact, Cutthroat Island often seems like one long string of pirate tropes, homages, and stolen scenes. Great soundtrack, though, and Davis does well as a pirate captain.

Now is a good time to briefly point out the reality of women pirates during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy 1655 to 1730. Strictly speaking, we know of only two who can be truly said to be pirates of the Caribbean: Anne Bonny and Mary Read, the former of whom gets all the cinematic glory while the latter, if what Charles Johnson wrote about her is true even in part, was the real swashbuckling bad-ass of the twain.

If Johnson’s early eighteenth century account is true, Read had been thrice a soldier in disguise, then a pirate, and even a privateer, in disguise, and reportedly fought at least one duel against a male crew member. Of course, this may be entirely an invention of the author, and his account of Read’s army service may have been inspired by the real life of female soldier-in-disguise Christian Davies. Although a fictionalized account of her life was not published until 1739, her story was known at the time Johnson’s pirate book was written.

Whether a true tale or not, it’s not Read’s warrior-woman story that ends up in fiction and film, but that of redheaded Anne Bonny–or at least she’s assumed to be redheaded because she was Irish and reportedly had a hot temper. Bonny gets all the glory, even though she may have been merely the girlfriend along for a joyride with her bad boy pirate boyfriend. Or not. Likewise Mary Read. We simply don’t know enough about her or Mary Read. Johnson may have invented the past histories of both to “sex up” his book for sales potential.

Of course, it’s entirely possible that both were as bold as Charles Johnson described them, even if they only dressed as pirates when attacking at least one vessel, and remained in women’s clothing otherwise. And their piracy was pitiful, nothing more than cruising in a tiny 12-ton sloop, not the 40-ton sloop Johnson described, and robbing a few “mom and pop” local trading vessels, including a canoe paddled by an old woman — hardly the stuff of Hollywood. Of course Johnson had to exaggerate for the sake of book sales!

Bonny, though gets all the attention, thanks largely to her relationship with “Calico” Jack Rackham. Writers are often lazy, and it’s easier to combine Read’s martial prowess with Bonny’s reported temperament and relationship with Rackham. However, not all writers who fictionalize the female pirate pair are as lazy. Some, including Erica Jong, have balanced their accounts of the two women.

But it’s Read, in my opinion, who deserves a movie.

Perhaps Anne Bonny, the assumed redhead, has also given us the redheaded part of the redhead in the red dress trope.

There are no other known women pirates of the Golden Age but for two who were technically pirates under the law, each having participated in utterly inept attempts at petty piracy, one of them comically so. Notably, two of the most commonly cited women pirates of the era were not pirates at all (please please please ignore Wikipedia!): Jacquotte de la Haye is entirely fictional, a creation entirely of author Leon Treich (Les Gentilshomes de la Flibuste, 1944, a factual-fictional account of buccaneers and some pirates written for a juvenile audience), and Anne Dieu-le-Veult, a wealthy widow, married the famous Laurens de Graff after his buccaneering days. She was never a member of his crew, nor is there any evidence that she was a member of any other crews. Treich is also responsible for exaggerating myths about Dieu-le-veult to an even greater degree, and even imaging deeds that never happened (including the utter nonsense that de Graff died in battle at her side).

More detail on Rackham, Bonny, and Read can be found here.

Likely though, there were real buccaneer and pirate women we’ll never know about because they remained in disguise. The common sexism of the day prevented women from becoming obvious members of a pirate crew. In fact, it’s probable that Anne Bonny and Mary Read (in Read’s case, after she revealed her sex) were part of John “Calico Jack” Rackham’s crew only because it was very small, no more than a dozen or so aboard a twelve-ton (that’s very small) sloop.

Pirates by majority vote could override their captains anytime but in action, and a larger crew would doubtless never have permitted women aboard as equals. In general, women were forbidden among early eighteenth century pirates except as prisoners, and even then pirates preferred to keep them away out of fear of indiscipline among the crew.

Red dresses pop up in other pirate or pirate-associated films as well, but it’s hard to tell if they qualify as tropes. Red is a popular dress color, after all: it stands out well and is often associated with temperament and sexual license, accurate or not.

In 1952’s Blackbeard the Pirate starring Robert Newton, heroine and damsel-in-distress Linda Darnell, in the scene most often used for advertising posters and lobby cards, is often depicted in red rather than the actual dark blue in the film. Clearly, there is marketing value in placing a woman in red clothing. In some cases she is even depicted as redheaded rather than as raven-haired as in the film and in life.

Honorable mention must go to pirate queen Black Sheba in George MacDonald Fraser’s comic novel The Pyrates (1984): “she donned her scarlet silk breeches and shirt, buckled her dimanté rapier at her hip, drew on her long Gucci boots, exclaimed at the state of her coiffure, clapped on her plumed picture hat, dapped a touch of Arpège behind her ear, and then spent ten minutes selecting one long earring and applying her lipstick.” She is by far the fiercest and sexiest of all the pirates in the book–a pirate queen as only a novelist or Hollywood could create.

A phrase in the novel, “dark and sinister woman…,” gives away part of her inspiration: she’s at least to some degree a female Captain Hook, the wordplay on the color of her skin notwithstanding. (“Proud and insolent youth,” said Hook, “prepare to meet thy doom.” “Dark and sinister man,” Peter answered, “have at thee.”) Even so, Fraser in the afterword describes the pirate queen as “a Dahomey Amazon with echoes of Lola Montez, Queen Ranavalona, and a pantomime principal boy,” all characters from his Flashman novels. She’s clearly inspired by other characters as well. Note also that the character of Bilbo–named for the slang term for sword (i.e. a blade from Bilbao, Spain) and not for the Hobbit–is according to the author, “Basil Rathbone playing a raffish Captain Hook.”

Also, at one point Fraser dresses one of the two more “traditional” heroines, Lady Vanity, in a maroon velvet dress, almost certainly, given his numerous other homages to piratical Hollywood and fictional tropes, in honor of classic pirate film heroines in red, and quite possibly of Disney’s woman in red as well. The dust jacket below shows another of the heroines, Dona Meliflua, also in red.

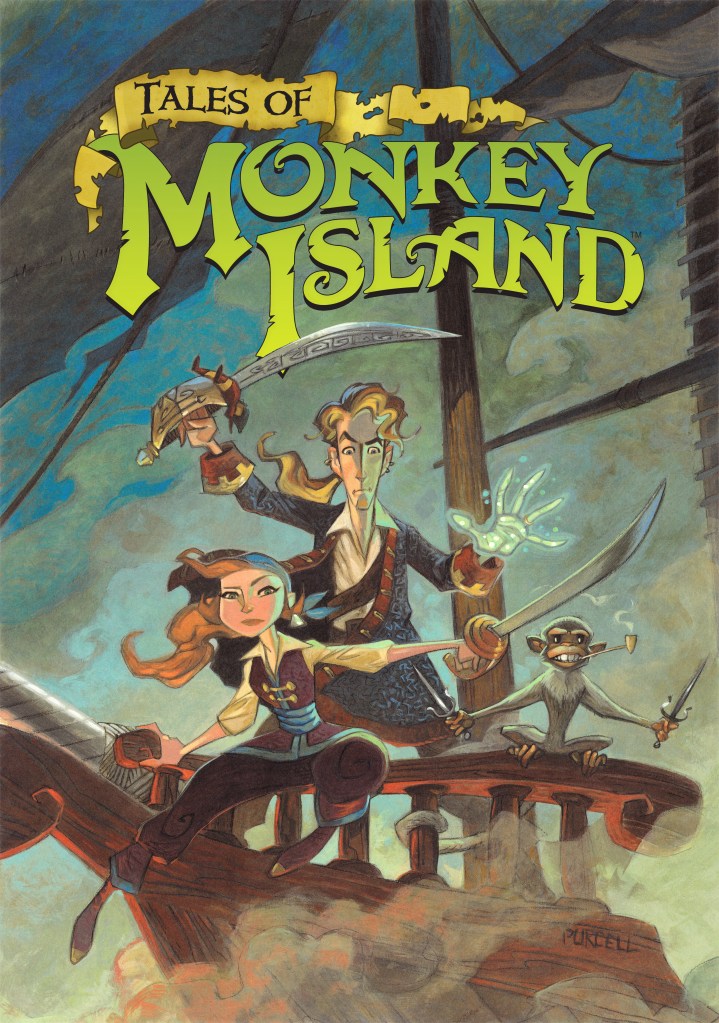

In video games, Elaine Marley from the several Monkey Island games was surely inspired at least in part by redheaded “Spitfire” Stevens aka Maureen O’Hara.

Cover art for two of the Monkey Island games, courtesy of The Monkey Island SCUMM Bar and Lucas Arts Posters at the International House of Mojo. Original box art by Michael Koelsch (left) and Steve Purcell (right).

We might also consider the possibility that Nami from the One Piece anime, manga, and Netflix series was possibly inspired at least in part by the various redheaded pirate queens.

Nami as depicted in the film One Piece Redd (2022), and as played by Emily Rudd in the live action Netflix series (2023).

Nonetheless, Blackbeard the Pirate and other films (and novels!) notwithstanding, there is a possible ultimate origin for the redhead in red dress trope prior to the Disney attraction — in fact, its inspiration perhaps, or at least part of it.

In 1952 Columbia Pictures released The Golden Hawk, a pirate film, albeit one technically about French and Spanish privateers in the Caribbean in the late seventeenth century. The film is based on the novel by Black author Frank Yerby.

The male lead is Sterling Hayden playing Captain Kit Gerardo. His acting appears a bit wooden by Hollywood pirate captain standards until you read his biography: a true tall ship captain in his youth, later a Silver Star recipient and US Marine Corps officer assigned to the OSS (the precursor to the CIA covert operations department) behind enemy lines in World War Two. In other words, he was playing himself as a privateer captain. Even so, Variety magazine wrote that Hayden was “out of his element as the gallant French privateer…” Hollywood goes for (melo)drama, but most real captains are far more quiet and self-assured. They have to be. But I digress.

The female lead was red-haired Rhonda Fleming, one of the “queens of technicolor,” the most famous of whom was Maureen O’Hara who starred in several swashbucklers and whom some critics suggested would have been better in the role–and better for its box office.

Fleming’s character in the film is “fiery,” to be expected of the popular genre, including the Frank Yerby novel on which the film was based. In one scene–SPOILER ALERT!–she shoots Kit Gerardo when he makes “romantic overtures” to her, then leaps out a stern window and swims ashore. No swooning heroine she, thankfully, nor one to put up with sexual harassment or worse.

In a few scenes, Fleming, whose character’s real name is Lady Jane Golfin, wears a luxurious green dress. But in most lobby cards, tinted publicity stills, and movie posters, it’s red.

More importantly, Rhonda Fleming plays a buccaneer, Captain Rouge (that is, Captain Red)–she was also a pirate!

We may have simultaneously moved forward while also coming full circle. 🙂

Postscript July 22, 2020: This bears repeating: Please, please, please do not use the Wikipedia entry on women pirates for research! Or on any piratical subject! At least not if you’re looking for facts. 🙂 Wikipedia has a number of flaws in many of its articles on piracy (and in many other areas as well), including factual errors, incomplete information, inadequate or incorrect sources, trolling (intentional factual misrepresentation to trigger a reaction or otherwise for fun), severe ideological slants leading to inaccuracy (i.e. deliberate “scholarly” misrepresentation, often in support of social or political ideologies, ranging from the far left to the far right, attributed to pirates, yet running counter to historical fact), and fairly constant regressive, incorrect changes to accurate information. Some articles on piracy are occasionally quite accurate, but many are all too soon revised inaccurately again.

Copyright Benerson Little 2020-2026. First posted July 8, 2020. Last updated February 21, 2026.

Evoking Swashbuckling Romance: Hollywood Pirate Ships & Shores in Miniature, & More

A brief place-holder blog post (and at the bottom a not quite shameless plug for Blood & Plunder by Firelock Games) while I finish several more challenging posts in the queue.

Before the advent of CGI, many swashbuckler films used models of ship and shore, along with full-size ships built on sound stages, to both recreate environments no longer available and also to save money. To some degree the early miniatures may seem quaint today, as compared to CGI, although in my opinion bad CGI is worse–more jarring to the eye–by far than an obvious model.

These old sets and scenes evoke nostalgia for the entire spectacle of old Hollywood swashbucklers: the cinemas with their great screens and clicking film projectors, the lasting impressions left by thundering broadsides and clashing swords, and above all the image of pirate ships in tropical waters.

For fun, here are a few.

Publicity still, The Sea Hawk (Warner Bros., 1940).

Above, the Albatross, commanded by Capt. Geoffrey Thorpe (Errol Flynn) arrives in a secluded cove on the Isthmus of Panama in order to raid the silver trains. The film scenes set in the Old World are in black and white, while those in the Americas are in sepia.

Only the film title is actually based on the novel by Rafael Sabatini, which tells the story of an English gentleman who turns Barbary corsair in an act of revenge. The 1940 film is a not even thinly-veiled wartime propaganda piece, albeit an enjoyable one. English sea dogs are renamed in the scrip as patriotic sea hawks suppressed by treasonous machinations until the doughty hero (Errol Flynn) reveals the treachery and England arms the sea hawks against Nazi Germany Imperial Spain. For more information try The Sea Hawk, edited by Rudy Behlmer. It’s a fun read for anyone interested in the script and the film’s history.

Publicity still, Captain Blood, Warner Bros., 1935.

Next, we have the models of Port Royal and the French flagship used in the finale. This image is not of an actual scene from the 1935 Captain Blood starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone, but of the set prior to shooting.

Detail from the photograph above.

Of course, the real Port Royal looked nothing like this. It was actually crammed with English-style brick buildings of two and even three floors, unlike this Southern California Spanish colonial revival-influenced town. But it’s sets like these in Hollywood swashbucklers that have influenced our notions of what the seventeenth century Caribbean looked like. In fact, the region at the time had a wide variety or environments and architectures.

Publicity still, Captain Blood (Warner Bros., 1935).

Above we have the battle in Port Royal harbor during the finale of Captain Blood: the Arabella on the left versus the French flagship on the right. N. B. Royal sails (the smallest on the ship on the right, the fourth sail from the bottom) were not used in this era. Their use here is an anachronism. In fact, only exceedingly rarely was the topgallant sail (the third sail from the bottom, used on “tall ships” on the fore and main masts) seen on the mizzenmast or sprit-mast on the bowsprit. I know of only two seventeenth century instances, each noted as being highly unusual. One was Kidd’s Adventure Galley in the very late seventeenth century, the other was a Spanish ship in 1673.

Publicity still, The Black Swan (Twentieth Century Fox, 1942).

A pirate ship under full sail in action against ships at anchor and shore targets during the finale of The Black Swan starring Tyrone Power and Maureen O’Hara. The film is based on the somewhat similar novel by Rafael Sabatini.

Screen capture, The Spanish Main (RKO 1945).

A pirate ship sailing into Cartagena de Indias under the guns of a castle in The Spanish Main starring Maureen O’Hara and Paul Henreid.

Publicity still, Against All Flags (Universal International Pictures, 1952).

Over-large pirate ship and treasure ship of the “Great Mogul” in Against All Flags. The ships are engaged under full sail, a practice generally not seen in reality except in the case of a running fight, but quite common in Hollywood because it looks good. Here, both ships would have stripped to “fighting sail” for a variety of reasons, including simplified ship-handling in action. The film stars Errol Flynn, as Brian Hawke, in one of his last swashbucklers (followed finally by The Master of Ballantrae in 1953 and Crossed Swords in 1954). It also stars Maureen O’Hara wielding a sword as Prudence ‘Spitfire’ Stevens, something I always enjoy.

Image courtesy of Firelock Games.

And now, a not quite shameless plug for Firelock Games’s Blood & Plunder tabletop war game of piracy and much, much more–one need not take the side of pirates to play. A full spectrum of peoples and forces are available.

Full disclosure: I’m the game’s historical consultant, and I thought it would be fun to compare the Blood & Plunder models to the film models above.

So, above and coming soon: a small Spanish galleon. Historically accurate, the model also evokes the best of old Hollywood swashbucklers.

Image courtesy of Firelock Games.

A small Spanish frigate engaged with a French brigantine.

Image courtesy of Firelock Games.

Spanish and French brigantines engaged near shore. Which is the pirate? (Answer: either could be!)

Photo courtesy of Firelock Games.

A small fluyt (in English a pink, in French a flibot, in Spanish an urqueta, on the left; a galleon at center; a brigantine on the right.

Photo courtesy of Firelock Games.

Close up action!

Image courtesy of Firelock Games.

Brigantine crewed by, I believe, French flibustiers.

Information about the game is available on Facebook and the company’s website.

Copyright Benerson Little 2018. First posted April 16, 2018.

Holiday Wishes! (And Some Hollywood Swashbuckler Biographies)

Wishing everyone Happy Holidays, however you celebrate them! Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukah, Happy Kwanzaa, Happy Solstice, Happy New Year (Western and Chinese)–all and more as you wish and please. It’s a secular Christmas here: Santa Claus, reindeer and sleigh, Douglas fir tree (except this year due to the nation-wide shortage, we cut a Virginia pine locally instead), stockings hung by the chimney with care, homemade cookies, fire in the fireplace, books read to children (and to nearby listening adults), much gift giving, plus Basil Rathbone, Albert Finney, Michael Caine, George C. Scott, Mister Magoo (aka Jim Backus of Gilligan’s Island fame), Reginald Owen, and Seymour Hicks as Scrooge, plus occasional swords and sword adventure with musketeers and pirates (and dark rum left for Santa as he makes his rounds), along with the usual excellent food, drink, family, and good cheer.

That said, this is a blog and therefore a suitable place to give praise to the four swashbucklers in the image above, from the 1952 RKO film, At Sword’s Point, also released as The Sons of the Musketeers. The movie is not considered to be the best of its genre, yet is still better than most and worth watching just to see Maureen O’Hara wield a sword–and there’s more to see than just O’Hara’s swordplay and independence, although as noted she alone makes the film worthwhile.

So, from left to right…

Alan Hale Jr. as Porthos Jr.

Alan Hale Jr., a solid more-than-character actor appeared in many films but is by far best known for his role as Jonas Grumby aka “the Skipper” in Gilligan’s Island.

Publicity still of Alan Hale Jr. as Jonas Grumby aka “The Skipper” in Gilligan’s Island.

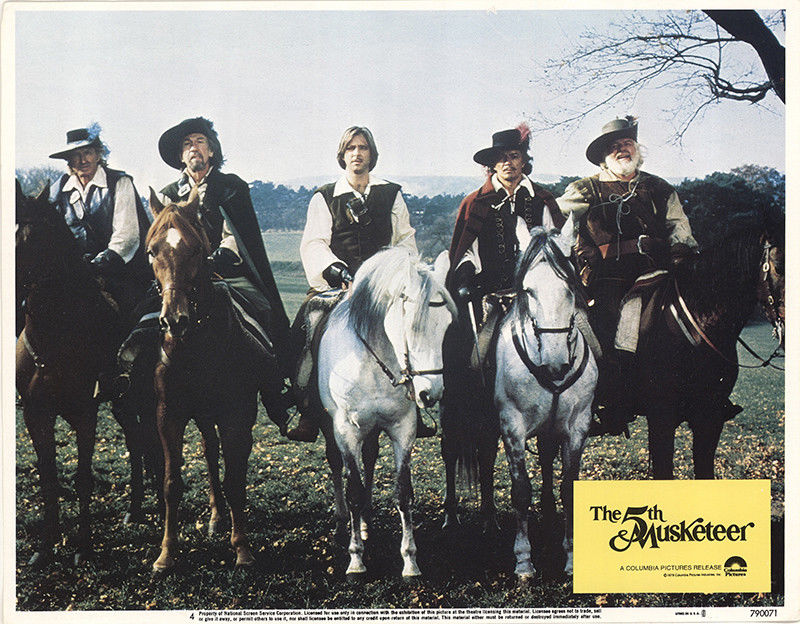

Hale Jr. also starred as Porthos Sr. in a 1970s version of The Man in the Iron Mask entitled The Fifth Musketeer, a film that rounded up a variety of aging actors who had starred in swashbuckling and adventure stage, film, or television, and tossed them in with luminaries such as Rex Harrison and Olivia de Havilland, with up and comers such as Beau Bridges and Ian McShane, and with the addition of Ursula Andress and Sylvia Kristel, the latter best-known for the erotic Emmanuelle films. But not even this sterling cast could hold the film together, even coming as it did on the heels of the recent Three Musketeers and Four Musketeers films.

Alan Hale Jr. (far right) as Porthos in The Fifth Musketeer (1979). From left: Lloyd Bridges (whom I once “saw” as an early toddler in a film theater in Key West while he was there filming Sea Hunt), Jose Ferrer, Beau Bridges (son of Lloyd), Cornel Wilde, and Alan Hale Jr. (Columbia Pictures lobby card, 1979.)

If Alan Hale Jr. looks familiar to fans of older films, he should, for as Porthos Jr. and Porthos Sr., Hale makes an homage to his father, Alan Hale Sr., who appeared in a fair number of swashbucklers, most famously The Sea Hawk, Robin Hood, and The Adventures of Don Juan, all starring his close friend Errol Flynn. In Robin Hood he reprised his role as Little John, having first played the character in the extravagant silent version by swashbuckling film star, producer, and director Douglas Fairbanks. He took up the role again in 1950 in Rogues of Sherwood Forest. Hale, born Rufus Edward MacKahan, co-starred in several other Flynn films as well: Dodge City, Virginia City, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, and several others for a total of thirteen films.

Alan Hale Sr. as Little John in The Adventures of Robin Hood (Warner Bros., 1938), starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, Basil Rathbone, and Claude Raines.

Screen capture from the Gilligan’s Island Christmas episode (“Birds Gotta Fly, Fish Gotta Talk”), 1964. Alan Hale Jr. plays Santa, whom the castaways believe is the Skipper. But is Santa actually the Skipper?

Maureen O’Hara as Claire, Daughter of Athos

I’ll doubtless devote an entire post one day to Maureen O’Hara and her swordplay in swashbucklers. Alas, as often as she wielded a sword in a swashbuckler, she did not in another. In The Spanish Main and The Black Swan, the most successful of her swashbucklers, she had no sword-in-hand (although Binnie Barnes took up the blade admirably in the former). So, until I post a full article on O’Hara, here are a few images of the strong-willed, independent, red-headed, Dublin-born and raised actress (or actor, if you prefer):

Maureen O’Hara engaging multiple adversaries in At Sword’s Point.

Not dressed for swordplay. O’Hara in At Sword’s Point.

Fencing a Cardinal’s guard in At Sword’s Point, O’Hara still not dressed for swordplay.

As Spitfire in At Sword’s Point, co-starring Errol Flynn in his last swashbuckler. O’Hara carries the film and in the climax gets to engage in swordplay once more on film.

O’Hara engaging blades in Against All Flags.

Maureen O’Hara in one of her most famous roles, in the holiday classic Miracle on 34th Street. With her are Edmund Gwenn and a very young Natalie Wood.

Cornel Wilde as d’Artagnan Jr.

Born to Czech-Hungarian parents in Manhattan, Cornel Wilde often traveled with his father to Europe where he picked up several languages and, reportedly, skill at fencing. An avid and outstanding fencer, Wilde turned down membership on the US saber team for the 1936 Olympic Games in order to accept a theatrical position–a decision few fencers would ever consider making. It’s one thing to give up a potential or possible eventual position on an Olympic fencing team, quite another to give up an offered one. That said, the several actors I know with fencing experience might very choose an opportunity in the form of a middling role in film or theater over fencing in the Olympic Games, although I’m sure the decision wouldn’t be an easy one.

Wilde fencing-brawling in At Sword’s Point.

An accomplished actor, Wilde’s looks, swordplay, and athleticism led him to starring roles in numerous swashbucklers.

Wilde fencing Herbert Lom (of the Pink Panther films fame) in The Star of India.

Wilde furthered his fencing study in the US under famous Hungarian-born fencing master Joseph Vince who had a studio and fencing supplier company first in New York City, later in Beverly Hills. Wilde even illustrated Vince’s book on fencing.

Illustration by Cornel Wilde for Fencing by Joseph Vince.

When fencing jackets were indeed dashing. My first jacket, purchased in 1977.

If I have a favorite of Wilde’s films, it is almost certainly The Naked Prey. Relegated to cult film status by many today, it is best considered as an action art film, if such a category exist. In any case, it is a minor classic (Criterion has released it), notwithstanding mixed reviews. Wilde was fifty-two when he produced, directed, and starred in the film, a physically demanding starring role for anyone, not to mention that he was ill most of the time–demands that most men even half his age probably could not have handled.

Lobby card from The Naked Prey (1965).

Dan O’Herlihy as Aramis Jr.

An accomplished actor who should be better known today, O’Herlihy played a variety or roles during his long career, ranging from several swashbucklers to serious contemporary roles to character pieces such as “The Old Man” in the RoboCop films.

As Alan Breck [Stewart] in Kidnapped, also starring Roddy McDowell. (1948.)

O’Herlihy was nominated for an Oscar for his starring role in Robinson Crusoe, directed by famous-auteur-to-be Luis Buñuel.

Robinson Crusoe poster, 1954. The film was produced and made in Mexico for the English-speaking market. A Spanish language version was also produced.

Ever the distinguished-voiced actor’s friend: audio books.

Audio book on vinyl: Dan O’Herlihy reading A Christmas Carol. Four records at 16 RPM, I can’t even recall that speed on a turntable… (The Billboard, October 26, 1959.)

HAPPY HOLIDAYS!

Copyright Benerson Little 2017-2018. First posted December 20, 2017, last updated January 7, 2018.