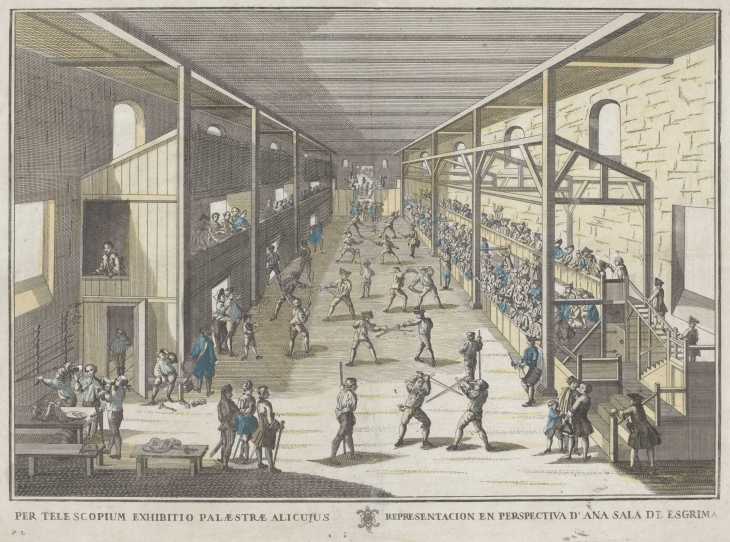

German fencing school mid-eighteenth century. Not only is the smallsword being practiced (or competed in, given that there are a few marshals or directeurs de combat) with foils, but also sword and dagger, two-handed sword, dusack (a short cutting sword similar to a cutlass or falchion), halberd, and quarterstaff. The galleries and stands are full of spectators, fencers and fighters are taking refreshment, and women are (probably) feigning interest in the martial spectacle. The Rijksmuseum, the source of this image, has three high resolution versions, each with slightly different coloration.

The fencing salle, or school or club, if you will, is a hall of mirrors to the soul, and if not to the soul, then at least to fundamental character. It is a magical place whose special sights and insights are enriched by a special language accented with the unmistakable sounds of blade on blade.

Perhaps Rafael Sabatini put it best in Scaramouche (1921):

“From a room beyond, the door of which was closed, came the stamping of feet, the click and slither of steel upon steel, and dominating these sounds a vibrant, sonorous voice speaking a language that was certainly French; but such French as is never heard outside a fencing-school. ‘Coulez! Mais, coulez donc!…So! Now the flanconnade—en carte…And here is the riposte…Let us begin again. Come! The ward of tierce…Make the coupé, and then the quinte par dessus les armes…O, mais allongez! Allongez! Allez au fond!’ the voice cried in expostulation. ‘Come, that was better.” The blades ceased.”

Stewart Granger (right) as Andre Moreau in Scaramouche (MGM 1952), a film about the French Revolution that avoids depicting its mass brutality. Still, it’s an enjoyable diversion. Fencing master Doutreval of Dijon (a character made up for the film–in the book it is Bertrand des Amis), played here by John Dehner, gives a much too wide invitation upon which Granger attacks in tempo. Appropriately, or mostly so, neither master nor student is wearing a mask. Although masks would soon become fairly common, many early masters eschewed them, believing they would lead to sloppy fencing. They are used in the book, however. Inappropriately, neither man wears the fencing shoes common to the era. Happily, though, Doutreval quotes a now-famous description of how to hold a foil: like a little bird, not so loose that it might escape, and not so tightly that you choke it. (The original, as opposed to film, quotation: “Tenez votre épée comme si vous aviez dans la main un petit oiseau: assez ferme pour ne pas le laisser échapper, mais pas assez fort pour l’étoufler.“) The quote is not used in Sabatini’s book. Although I once heard it attributed to Louis Justin Lafaugére, I’ve only found it in Essais sur l’Escrime by Richard de la Pervanchère (1867). Given that Jean Heremans choreographed the swordplay, we might perhaps give him credit for resurrecting it. Of course, this grip is not quite appropriate today, although I do teach it for use with the aid fingers (middle, ring, and little): the modern vice grip between manipulators (thumb and forefinger) would not be good for the bird in the hand… Shifting now to the other subject of this post, that of behavior on strip, co-star Eleanor Parker said she and everyone on set found Stewart Granger insufferable.

And with the fencing salle come a few rules for honorable deportment, as suitable today as they were in the past. And, as the lessons of fencing are apt for the world beyond, so too are the core of its courtesies and other appropriate behaviors.

Many have been recently eroded, at least to a greater degree than in the past, among modern or “Olympic” fencers, largely due to the Federation Internationale d’Escrime’s rather abject submission to the International Olympic Committee’s desire to have Olympic sports present [melo]dramatic “spectacles” designed solely to increase viewership and therefore income from advertising. National fencing bodies typically willing to go along with almost anything as long as it means that fencing will remain an Olympic sport, no matter in what form, play a significant role as well.

Even so, all styles of swordplay are seeing rules of fencing etiquette debased by the competing egos of many fencing masters, teachers, coaches, and fencers themselves, in addition to the general degeneration of civility, including the practices of honor and humility, these days.

N.B. I am by definition a “modern” fencer, although I also practice classical and historical fencing. Any criticisms therefore are not those of an outsider attempting to disparage modern fencing or other forms of swordplay.

“Der Fechtende Student” by “Dendrono” aka Johann Georg Puschner (Nuremberg, 1725). Note how the foils are hung, the fencing shoes under the bench, the fencing master with his plastron, the list of rules posted on the wall, the large windows for light, and the vaulting horse, common in fencing salles at the time. The foils are very typical of the German style.

Here therefore are a few rules and guidelines of recommended behavior in the salle, from recent years to past centuries, with some of my own thrown in near the end of the post. I am intentionally avoiding excessively in-depth commentary on the behavior of many fencers today, for it would probably quickly turn into a near-rant. Thankfully, the majority of fencers today, in all forms of legitimate swordplay, still behave with excellent deportment on the strip–but it doesn’t take too many bad apples to spoil the reputation of a sport or other organized skill.

I’ll make two important points up front. First, the best way to teach good behavior in the fencing salle, and everywhere, is by example. Younger fencers are far more likely to behave with courtesy and dignity if they have the good examples and associated expectations of their fencing teachers, veteran fencers, and experienced peers. It starts at the top. Unfortunately, some of the most egregious violations are often found here.

Second, I don’t want this to turn into an “Olympic” or sport fencers versus classical and historical fencers. I’m ecumenical when it comes to fencing. I’ve practiced many forms of swordplay over the past forty or so years, and I’ve seen plenty of poor behavior in the form of various violations of the following rules and guidelines among members of all three groups, and among others as well. But to repeat, most fencers, no matter their preferred form of swordplay, still manage to behave well on the strip.

“Le Maistre d’Armes” by Nicolas Bonnart, from his Recueil des Modes de la Cour de France, 1678-1693. (LACMA)

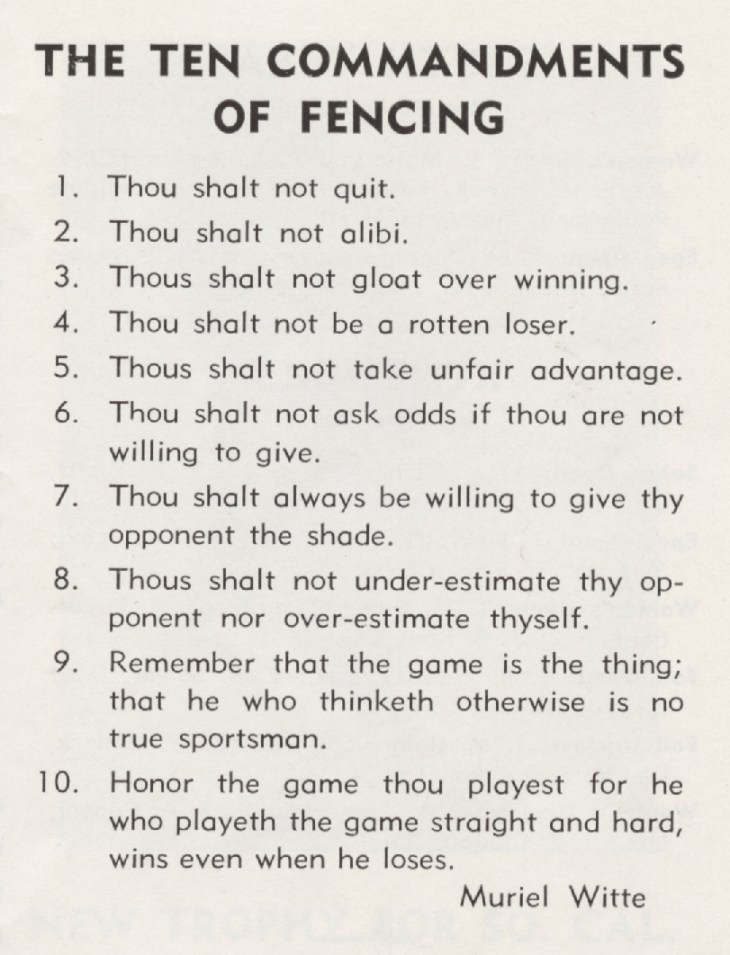

Muriel Witte in American Fencing magazine, 1966

Muriel Witte, American Fencing magazine, March 1966.

Regarding number 6, some fencers past fencers would ask for or accept odds, and some today do so as well, either by having the weaker fencer’s touches count for more, or by setting a goal the weaker fencer much reach in a five, ten, or fifteen touch bout. For example, the weaker fencer wins if he gets to five touches before the stronger gets to ten. This was never a practice in the salles where I learned to fence, and I have never engaged in it. The odds are rarely well-balanced, usually favoring one or the other of the fencers.

A better practice is to avoid setting odds or a handicap, and instead set a goal of touches against your opponent, averaging them over time and working to score above this level if you’re the weaker fencer, or to improve the distance if you’re the stronger (and if you’re significantly stronger, just fence and don’t worry about the distance between scores). Too often the more experienced fencer suggests odds that will push him or her, but such odds often don’t push the weaker fencer enough. For example, a balance of 15 to 5 strong to weak may be good for the stronger fencer, but a better balance might be 15 to 8 in order to push the weaker fencer more. Further, the setting of odds by the stronger fencer can often come across as patronizing, even arrogant, at times.

Number 7 dates to the days of gyms which made much use of natural light through high windows, and which some poor sports among fencers would take the side of the strip with better light (although in bouts for touches with dry weapons, fencers swapped sides after one fencer scored three touches or half the time expired). In fact, an old dueling tactic was to place your adversary on disadvantageous ground, for example with the sun or wind in his (or at times her) face. Dueling practice in the late 19th and 20th centuries tried to minimize any advantage one adversary might have over the other by way of terrain or weather.

Outdoor fencing is not done often enough these days, although some of us still enjoy it. Unfortunately, it’s no longer permitted as a format for earning ratings in epee by the USFA. (Or as it’s now called, USA Fencing, and prior to that US Fencing. It’s hard to keep up with the name changes. In fact, it was the AFLA–the Amateur Fencers League of America when I started fencing more than forty years ago.) And with the addition of relatively new ratings (D’s and E’s) plus a direct elimination format that vastly increases the likelihood of earning a rating as compared to the old pool system (which unfortunately produced a large percentage of under-rated fencers), we find a flood of rated fencers these days. As such, modern fencing has unfortunately become for many fencers “all about the rating,” with the result that there are far fewer “fun” tournaments than in the past. Nonetheless, there’s no reason not to hold outdoor epee tournaments on occasion, ideally set in picturesque or historic venues. I have fond memories of an outdoor epee event held on the grounds of a Florida beach hotel, for example.

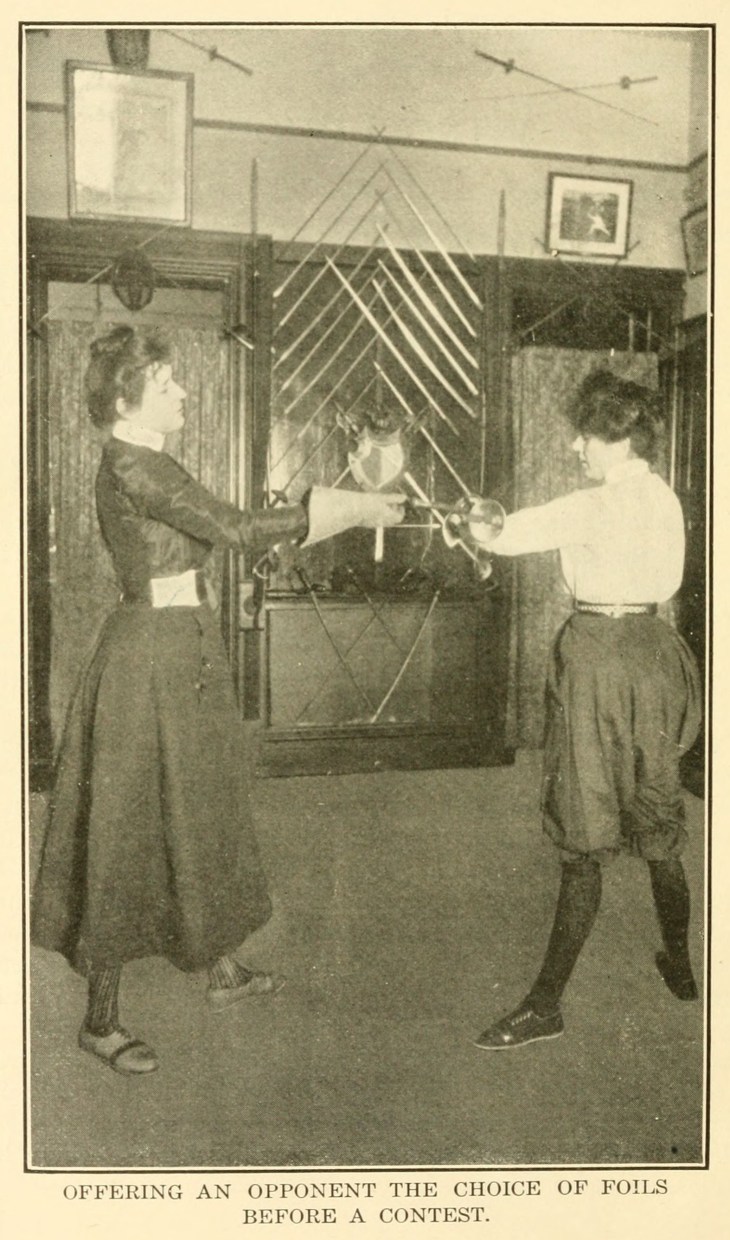

From The Art of Fencing by Reginald and Louis Senac, “Professional Champions of America,” 1915.

“Decalogo Dello Schermidore” by Aldo Cerchiari and Edoardo Mangiarotti

From their book La Vera Scherma (Milan: Longanesi & Co, 1966). The commandments are also posted on the website of the famous Milanese Mangiarotti Fencing School. Edoardo Mangiarotti was easily one of the few truly great epeeists of the past century. All fencers should strictly abide by these precepts of fencing honor and fair play:

In translation…

1. Remember that you are the representative of the noblest of all sports. It unites fencers from around the world in the same ideal.

2. Practice your sport unselfishly and with absolute loyalty.

3. Be a gentleman or lady on the strip and off, from sport to social events.

4. Do not discuss fencing if you have not learned fencing and its rules.

5. Learn how to lose with dignity and win with honor.

6. Respect your opponent at all times, whoever he or she is, but try to overcome him or her in combat with all of your energy.

7. Remember that until the last thrust your opponent has not yet won.

8. Serenely accept a defeat rather than take advantage of a victory obtained by deception.

9. Do not step onto the fencing strip with defective weapons or with the white uniform in disarray.

10. Honor, respect and defend your name, the prestige of your master, the colors of your club, the flag of your country.

![[Rencontre_d'escrime_féminine_entre_Mme_[...]Agence_Rol_btv1b6910360f](https://benersonlittle.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/rencontre_descrime_fc3a9minine_entre_mme_-agence_rol_btv1b6910360f.jpeg?w=730)

“Rencontre d’escrime féminine entre Mme Rouvière et Alice [Aline] Guillemot, le 27 mai 1908, au Cercle Hoche.” Note the weapon racks on the wall, the formal attire, and the piste raised for the occasion. (Press photograph, Agence Rol, in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

A Variety

“No boast, threat, trick, or stratagem, which may wound the feelings, or lessen the equality of the combatants, should ever enter into the contemplation of a gentleman.”

—Joseph Hamilton, The Approved Guide Through All the Stages of a Quarrel, 1829

“Never lose on purpose, you must always fence to win for your honor!”

—Lajos Csiszar, quoted by student Roger Jones, former member of the US 1955 and 1957 epee teams, alternate to the 1956 US Olympic epee team, member of both the AFLA (i.e. USA Fencing) and FIE rules committees, in an article dating to 2000, and in later conversation with me. The quote itself dates to the 1950s, and probably earlier. Csiszar was one of Italo Santelli’s three protégés (assistant fencing masters).

Roger himself best describes how Csiszar came to tell him this:

“The first time I fenced in Europe, I learned that cheating was part of the sport, unlike in the U.S. It was common for countrymen to throw bouts to the favorite during the early rounds, in order to improve his seeding for subsequent rounds. Csiszar hated this, as did I. He told me, “Never lose on purpose, you must always fence to win for your honor!” In the 1957 World Championships, an Austrian approached me just before our bout, which was the last one in the round. He pointed out that I would be eliminated even if I won, but that if he won, he would go on into the next round. He asked me to lose, saying “You speak German, therefore, we must stick together.” I refused, and then defeated him 5-2. Afterwards, I told Maestro about the incident, and he hugged me, saying “I knew you would always fight for your honor.” He made me feel so proud.”

—Roger Jones, “Fencing Generations,” manuscript, November 2000. Roger was an outstanding swordsman, business executive, writer, former naval officer, and gentleman who deplored the notion of gamesmanship and cheating in fencing. He passed away a few years ago.

“Your complete swordsman must be one who can place his hits with a gallant good grace, but one also who will not allow a clumsy opponent to prevail himself on any hap-hazard thrust.”

—Egerton Castle, “Swordsmanship Considered Historically and as a Sport,” 1903

“Gallant good grace” is too often forgotten today.

“Don’t flatter yourself in your Lessons, and still less in Assaults.”

“Be not angry at receiving a Thrust, but take care to avoid it.”

“Be not vain at the Thrusts you give, nor shew Contempt when you receive them.”

—Jean de Labat, L’Art en Fait d’Armes, 1692, as translate by Andrew Mahon, 1730

Labat has lots of good advice still relevant today.

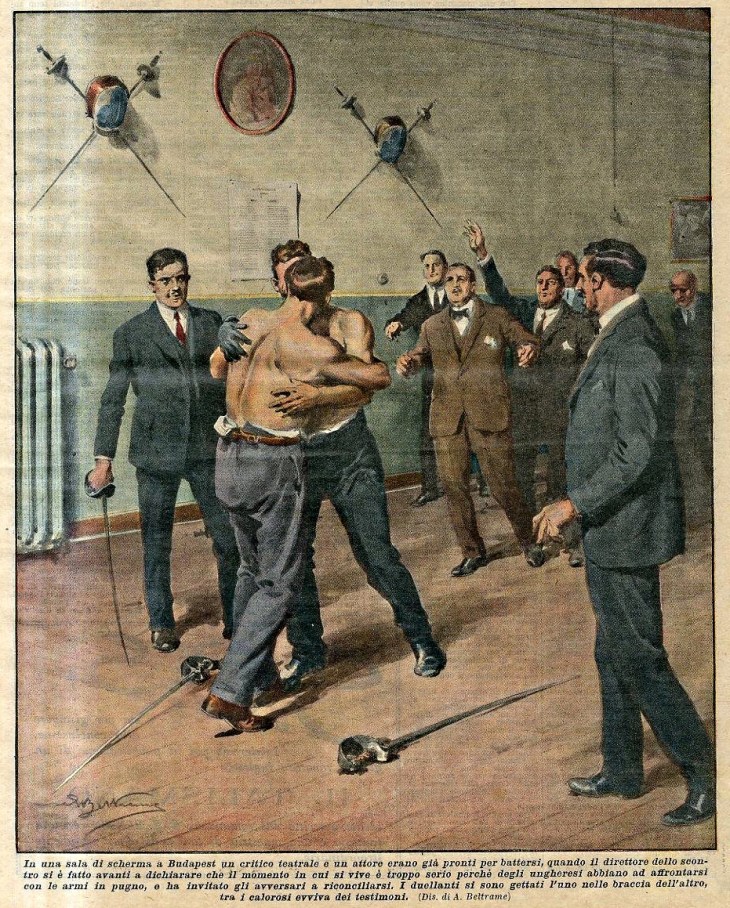

Immediate aftermath of a 1931 duel in a Budapest fencing salle–Salle Santelli, perhaps? The old master was known to regularly host duels. Hungarians were rabid duelists at the time; one newspaper article estimates six hundred annually. (A. Beltrame, for the cover of La Domenica del Corriere, 20 December 1931.)

“‘I have never,’ says M. [Ernest] Legouvé, ‘met a single fencer who would not–say once a year–deny that he had been touched when the hit was palpable. It is so easy to say ‘I did not feel it,’ and a hit not recognised does not count.'”

—H. Sutherland Edwards, “Fencing Schools,” Old & New Paris, vol. 2, 1894.

To summarize the quote above: You should always declare all touches against you when are fencing ‘dry’ in the salle!

That said, some masters will suggest that in the case of a competitive bout you leave it to the director and jury. I in turn leave this to your discretion and sense of honor. Personally, I would declare an obviously good touch unremarked by the judges.

Of course, not all touches are always obvious to giver or receiver, and allowance must be made for the possibility that the adversary did not feel a particular touch. In epee it is common for many of us to let our practice partner know that he or she hit, but that the touch was either late or flat.

There remains a vestige of the practice of declaring touches, or not declaring them, today in modern electrical epee fencing. In competitions on non-electric strips, I believe a fencer should declare a solid obvious touch on his foot in the case where the referee or floor judges have no opinion or state that no such touch was made. If, however, the fencer is unsure whether the touch was valid—when it might be just a scrape along the floor, a light touch, and so on—he or she should not declare it and leave the determination to the referee (who may overrule the floor judges). Even so, many coaches direct their fencers to never admit to a foot touch, or to any possible error that may favor the adversary, often justifying this on the premise that “It all evens out in the end.” I will always inform my adversary if, for example, I think his or her weapon is not working, and so forth. No victory in art or sport is worth anything if it is obtained through active or passive chicanery.

It is also a too-common practice, this not declaring of touches on occasion, among some classical and historical fencers today, and would be among modern fencers as well were it not for the electrical scoring apparatus. Certainly it was in the past when both saber practice and competitions were dry, and foil practice was typically conducted dry in order to suppress the “pig sticking” tendency induced by the electrical scoring apparatus. Over the past forty-two years I’ve met a number of fencers who were notorious for not declaring valid hits, over and above the possibility that they simply didn’t feel them. Of course, in saber there was a remedy: slowly escalate your hits, making them harder and harder until your adversary has choice but to declare them, if only by rubbing his arm… This was, and is, also the solution to saber fencers who consistently hit too hard.

Schermschool by Caspar Luyken, 1711. Note the unarmed hand position with the cutting swords as opposed to thrusting swords. Note also the danger to the unprotected face, the eyes in particular. (Rijksmuseum.)

And More Variety

“It is a polite custom to salute your opponent with your blade before the bout, and to offer him your hand at the end.”

“Once the fencer has taken the guard position, he must be considerate of his opponent. Neither fencer must talk during the bout. Fencing requires the greatest possible attention, and this may not be diverted in any way or for any reason except by fencing tactics.”

“In fencing against an opponent who acknowledges your superiority, sportsmanship demands that you do not make the most of your advantages; rather should you assist his swordplay as much as possible, and avoid placing him in a painful or ridiculous position by over-emphasizing your superiority.”

—Luigi Barbasetti, The Art of the Foil, 1932

Regarding Barbasetti’s third statement, it’s unfortunately far less common today to see fencers practicing this: many are unwilling, often solely for the sake of ego, to forgo even a few touches in the name of good sportsmanship. Another practice less often seen today is that of subtly “throwing” your opponent a touch to make up for a touch awarded against him or her due to a bad call by the director (known today as the “referee” in a bid to make fencing more “audience friendly”—I kid you not). Technically an illegal practice, its honorable intentions more than compensate for the breaking of the rule that the fencer must always fence to win.

Barbasetti’s first statement is now written into the rules due to the unsportsmanlike behavior in the past of a few fencers. See also Félix Gravé below.

“No Scholar nor Spectator without a licence from the Master, should offer to direct or give advice to any of the Scholars, who are either taking a Lesson or Assaulting… First, because without permission they take upon them to play the Master; And secondly, because they reprove oft-times their Commerads for the same very fault they themselves are most guilty of, although perhaps not sensible of, which when By-standers perceive, they smile at them (and with just reason) as being both ignorant and impertinent; therefore it would be a great deal more commendable in them, to be more careful in rectifying their own faults, and less strict in censuring others.”

—Sir William Hope, The Fencing Master’s Advice to His Scholar, 1692

More proof that not much has changed over the centuries.

“If you aren’t modest but show off your swordsmanship, you’ll be hated by people and be embarrassed.”

—Yagyu Muneyoshi, 17th century, translated by Hiroaki Sato.

“Though there are People of bad Taste in every Art or Science, there are more in that of Fencing than in others…”

—Jean de Labat, L’Art en Fait d’Armes, 1692, as translated by Andrew Mahon, 1730.

This is a sentiment I’ve heard more than once from much-experienced fencers over the last four or so decades, often expressed more narrowly: “There are more charlatans among fencing teachers than among any other sort of teachers.” Again, it’s more proof that not much has changed. The answer is simple: be of good taste, of good behavior, and of good knowledge, and let your behavior in the salle demonstrate this, whether you’re teaching or fencing. Or whatever, whenever.

“Schermschool van de Universiteit van Leiden” (Fencing School at the University of Leiden) by Willem Isaacsz van Swanenburg, after Jan Cornelisz van ‘t Woudt, 1614. On the walls are pole arms, matchlock muskets, dusacks, longswords, and foils (rapier). On the floor is the popular geometric outline associated with some forms of rapier footwork, along with a vaulting horse. Students are fencing with the rapier and the longsword, and one is practicing the various movements associated with loading, aiming, and firing a musket. (Rijksmuseum.)

“Don’t show any sign of bad temper if you are the loser.”

“Don’t get conceited, or be haughty, if you are the winner.”

“Don’t forget always to be modest and courteous.”

“If your adversary should prove far superior to you, do not show discontent or bad temper; do not be disheartened, keep up your style and do your best, no matter how badly you may be beaten. Take your defeat in the right spirit, it will help to improve you; take it as a lesson you needed. Remain always the “correct gentleman.”

“The use of the unarmed hand to parry an attack would be an incorrect movement; the use of the unarmed hand to make signs or attract the adversary’s attention would also be incorrect, whilst talking or conversing during the fight would be unruly.”

“[R]efuting a decision or arguing about the verdict of the judges would be considered bad form and ill-mannered.”

“Not shaking hands with an adversary after a match or a rencontre is a great lack of courtesy, and should be reprimanded. Saluting an adversary previously to the beginning of a bout should be done before placing the mask on the head.”

—Félix Gravé, Fencing Comprehensive, 1934

You may, of course, politely challenge the referee on the misapplication of a rule or the failure to apply a rule. Both occur far more often than they should, by the way, perhaps due in part to the modern “guild of referees” that values simple examination (and testing fees!) over experience in the practice and spirit of swordplay (and hasn’t improved refereeing at all). So know the rules, follow them, and be prepared to see them properly applied.

Even so, the best solution to bad refereeing/directing/judging is often the classic one: become good enough that the referee’s incompetence, bias, or, rarely, cheating, is irrelevant. In foil the old electrical scoring solution, and still a valid one today in foil and now saber too, was to make single-light touches, stripping the referee of the act of determining right-of-way.

As for shaking hands and saluting, the requirement has been written into the FIE and USFA rules due to repeated violations by a small number of fencers.

Second session of a recent beginning fencing class at the Huntsville Fencing Club. Photo by Amy Hitchcock.

A Few of My Own

These aren’t quite as eloquent or pithy as those above, but to quote Horace from his Ars Poetica in my defense, when I’m brief I’m often misunderstood.

1. My more modern take on Sir William Hope above: Do not give unsolicited fencing advice unless you’re an instructor giving it to one of your students, in which case it is by definition solicited. The principal exception is that of an experienced fencer politely suggesting a correction to an egregious error committed by a beginner. The fact that fencers often appear to accept such advice can be deceiving: it may simply be politeness or mere uncertainly as to whether the novice should tell the advanced fencer to please just be quiet and fence.

2. Given that many beginners are avidly seeking fencing knowledge, and can thus be easily misled, it is incumbent upon fencers giving advice to ensure that such advice is not only solicited and correct, but useful and appropriate to the recipient. Provide only what you know for certain from experience, never what you think you know. Importantly, make sure your advice is suitable the fencer you’re giving it to. Too often, fencers assume that what is good for them is good everyone. Further, many fencers have not yet reached the level at which all good advice may be of use. In other words, don’t provide advice that’s over the fencer’s head or inaccessible due to the level of technique required. And if you’re giving advice to show off: Don’t! In sum, don’t be a know-it-all. (See also Cerchiari & Mangiarotti #4 above).

3. For a stronger fencer to constantly shout “I missed!” when fencing a weaker fencer, or any fencer for that matter, is not only rude and patronizing, but ignores the fact that his or her adversary is probably missing often too.

At the very least it can be an annoying distraction.

“I missed!” is often shouted by some advanced fencers when hit by weaker fencers, as if to excuse the touch as an accident. In fact, advanced fencers often rely on the fact that weaker fencers often do miss–thus making an advanced fencer who shouts “I missed!” a double hypocrite.

Is it OK to occasionally shout “I missed!” when in spite of setting almost everything up perfectly you miss, perhaps because your point control was sloppy? Sure, but don’t overdo it. Is it OK do do so when fencing a friend who understands your frustration? Of course. But it’s never OK to do so in order to [arrogantly] dismiss a weaker’s fencer’s touch.

The fact is, if you get hit, you did something wrong and the other fencer something right.

More simply and more broadly: keep quiet when fencing so your adversary can concentrate.

A “traditional” modern fencing salle at Semmelweis University High School, Budapest, June 2014. My wife Mary and I visited it, escorted by our friend and fencing master Dr. Eugene Hamori, and especially by HEMA longsword and modern saber fencer Kristina Nagy who assists at the salle. (Authors photo.)

4. Related to number 3: Don’t be the fencer who is insufferable both in victory and defeat. Or in either. Or ever.

5. Avoid “showboating” and “grandstanding.” A particularly egregious example is that of a more experienced fencer moving close and opening the line widely, as if to say, “I’m wide open and even then you probably can’t hit me!” It’s an insulting practice, one that indicates insecurity on the part of the fencer doing it, and one the experienced fencer would never attempt with another fencer of the same or greater ability. It’s OK to move closer to a weaker fencer and open the line a bit more in order to work on developing one’s speed while simultaneously giving the weaker fencer the opportunity to score more in practice. It’s not acceptable to do so in a grandstanding or patronizing manner.

6. If you’re waiting alone on the only empty strip for someone to fence and a pair of fencers comes up to use the strip, you must turn it over to them. Most fencers waiting alone on a strip for someone to fence understand this and will automatically yield the strip to a pair of fencers who need it. Occasionally though, there are strip hogs. Fencers new to the sport are often uncomfortable asking a solitary fencer, waiting for no one in particular, to yield the strip. If you notice this, invite them both onto the strip immediately. And don’t be afraid to ask, even politely demand, a strip hog to yield the strip!

18/11/25, “Escrime féminine à la maison des étudiants.” Unidentified French fencing salle showcasing female students. (Press photograph, Agence Rol, 18 November 1925, Bibliothèque nationale de France.)

7. For coaches and parents, and especially, fencers: No cheating!

In particular, neither give nor, for fencers on strip, accept advice during a competition bout except during the one minute breaks in direct elimination. Strictly speaking, these breaks are the only time coaching or other tactical assistance is permitted during a bout. All other tactical aid during a bout is in fact cheating, including hand signs, “secret language,” and so on, not mention overt coaching. Don’t tolerate it! If you do, you have a personality flaw, plain and simple.

N. B. Before I continue, I must note that the USFA, or as it now terms itself, “USA Fencing” (marketing, marketing), permits coaching from the side of the strip by coaches or spectators as long as it doesn’t interfere with the bout. This is a US rule: try it in many places internationally and you’ll still get in trouble, as you should. Of course, the USFA now complains that such coaching is getting out of hand (surprise, surprise) and is now at work on a coaches code of conduct. In other words, the USFA is complaining about a problem it created, but won’t take up the appropriate solution, that of eliminating strip-coaching (and won’t admit it caused the problem, either).

So, to continue, and operating under the assumption that strip-coaching is and should be illegal…

Over the past two decades I’ve seen a new practice by a certain type of fencer in competition: the “whiplash,” that is, the head snapping around to look at the coach whenever the fencer is unsure about a touch or the progress of the bout, even in epee. Some fencers do this after each touch awarded to their adversaries. Should I challenge the call? Should I change my tactics? Should I do this again?

Sorry, but your coach is not permitted to respond in any way, notwithstanding that some coaches have trained their fencers to seek such advice during a bout. The sad fact is that many competitive fencers today are uncomfortable, some even to the point of near panic, if their coaches are not at the piste during their bouts.

A fair number of fencing coaches will “test the waters” during a competition by coaching during an early bout to see if the referee or bout committee will put a stop to it. If not, they’ll continue. Others will only try this during a challenging bout (that is, one in which one of their students is losing) during the direct elimination.

One of the most egregious violators I’ve seen was a coach who constantly decried the “cheating” by other coaches and clubs, including the giving of advice from the side of the strip during a bout, yet he was one of the most active practitioners I’ve ever seen, both as a coach on the sidelines and as a referee, although he “wisely”—if a cheater can be said to be acting wisely—limited it to critical bouts if experienced fencers and referees were present. However, he engaged in it nearly always if only inexperienced or easily intimidated fencers and referees were present—at least until someone showed up who would call him out on it.

And, on a related issue: No, the modern era of gamesmanship and cheating in fencing was not started by the Soviet Union’s entry into competitive fencing, some commentators notwithstanding, nor did this begin the general debasement in deportment on the strip. I’ll save this conversation for another day, but will note two things now: (1) there are plenty of early examples of these bad behaviors long prior to the Soviet Union entering sport fencing, and (2) it was notable how quickly nations other than France and Italy began regularly winning medals in epee and foil after the introduction of the electrical scoring apparatus–French and Italian judges could no longer pretend not to see touches.

In sum, if your child’s coach or teacher engages in any of these behaviors, tell him or her it’s unacceptable and that you’ll remove your child from the club if it continues. Many, perhaps most fencing coaches these days unfortunately follow a business model, which inevitably requires an emphasis on youth fencing: they’ll change their attitudes if a significant number of parents quit writing checks.

I’m a bit cynical about progress in this area, though, having watched for decades how often many parents, living vicarious second lives via their children, will accept or turn a blind eye to all sorts of egregious, even outrageous, behavior from coaches and teachers in sports and performing arts on the remote chance that their child will win nothing more than a local title or become a briefly notable local performer. And when greater rewards are at stake, far too many parents will turn a blind eye to almost anything.

Put plainly, a fencing bout should be a contest between two fencers and no one else.

Fencing’s best lesson is independent decision-making under stress.

A recent beginning class at the Huntsville Fencing Club. More than anything, a fencing salle is its fencers.

Fencing & Wine

Or, how fencing shows character and why this matters. Again I quote from H. Sutherland Edwards (1894) who is quoting dramatic author, not mention fencer and promoter of women’s rights and child education (and whose name was given to a perhaps phantasmagoric reef in the South Sea), Ernest Legouvé:

“Fencing has, moreover, its utilitarian value. It teaches you to judge men. With the foil in hand no dissimulation is possible. After five minutes of foil-play the false varnish of mundane hypocrisy falls and trickles away with the perspiration: instead of the polished man of the world, with yellow gloves and conventional phrases, you have before you the actual man, a calculator or a blunderer, weak or firm, wily or ingenious, sincere or treacherous… One day I derived a great advantage. I was crossing foils with a large broker in brandies, rums, and champagnes. Before the passage of arms he had offered me his services in regard to a supply of liquors, and I had almost accepted… The fencing at an end, I went to the proprietor [of the fencing salle] and said: ‘I shall buy no champagne of that man.’ ‘Why not?’ ‘His wine must be adulterated–he denies every hit.'”

Yes, character matters, then and now. And fencing reveals it better than anything other than the dire life-threatening circumstances of man and nature. A person who cannot be trusted on the strip should not be trusted off the strip.

Copyright Benerson Little 2018-2020. First posted July 20, 2018, last updated March 28, 2020.

Reblogged this on Marina Costa and commented:

For all those who love swashbuckling fellows…

LikeLike

[…] of these quotations are repeated in my post, Fencing Salles & Fencing Commandments, along with other advice and commentary. Please note that the list below is not complete, and never […]

LikeLike