“Jack Tar — armed literally to the teeth — with a combat sword in each hand for use, and a third between his teeth for ornament, encountered and overcame with ease eight ‘piratical skunks,’ seven slain with bloodless slaughter, the eighth contemptuously discomfited with a ‘quid o’ bacca.'” (Excerpted from “Realism” by Philip Beck, in The Theatre, September 1, 1883.)

This is the popular personification of the English seaman of the oak and iron era, the seaman of Drake and Myngs and Nelson — Jack Tar as he came to be known! His cutlass gripped by his powerful horny hand! No brigand, no pirate, nor even scimitar-armed Barbary corsair could stand against the doughty English (or rather, British!) seaman blade-in-hand! Much less in both hands and between his teeth, long before Roronoa Zoro (Zorro l’Ollonois in English — two famous names!) independently developed this famous three-sword style in the pirate manga, anime, and live action series One Piece.

Notwithstanding the clashing and sparking of swashbuckling blades we’re going to discuss, you may consider this short essay as a Public Service Announcement as much as a rendering of sword history. Yes, it mentions pirates and brigands and Jack Tars, and cutlass practice and swordplay and fencing tempo, but it is ultimately a PSA intended to correct the record, thus:

Every once in a while, when searching for swords within my areas of interest for research or occasionally for purchase, I’ll run across a nineteenth century “naval practice cutlass” with a steel blade and iron or steel basket hilt. Recently I found one quite by accident, listed at a tenth of what I’ve often seen these swords priced at, and so I purchased it.

Typically these are listed by auction houses and antiquarian arms dealers as practice cutlasses dating variously to circa 1860, or to “the Great White Fleet” or “the Spanish-American War,” or “between WWI and WWII.” Of course, the inability of dealers to properly date an arme blanche, even a practice one, more precisely is always a red flag. More on this in a moment. For now, we’ll assume the style of the “practice cutlass” I purchased was in service for a long time, as real and practice weapons often are.

My new “practice cutlass” is in near-mint condition, the blade largely un-nicked, the blackening of the basket hilt largely unscratched, and, curiously, a gold tint to the blade (quite common with some of these swords) still quite obvious. I was immediately taken with its excellent balance permitting credible feint attacks in spite of its weight. Most cutlasses, including practice weapons and blunted re-enactment arms, are clumsy affairs, more suited to direct attacks and strong simple parries at close quarters. But not this one! It has a lovely balance, one that immediately feels perfect in the hand. For a cutlass, it is sturdy with a solid feel, yet light at the tip in spite of its two and a quarter pound weight. Moulinets? With ease! The blade practically spins in the hand.

Immediately I contacted my friend and armes blanches expert and collector, not to mention expert designer and craftsman in models and miniatures, comic artist, raconteur, and more, Jim McDougall for his expert opinion. I paraphrase his reply: the blade appears to be a cut-down 19th century saber blade, the hilt sturdy but rather crudely put together, the grip emulating a circa 1900 style, and a generally ersatz appearance. (Any error in this summary of his words to me is mine alone.)

These observations would not alone implicate the “practice cutlass” as being fake, but there’s more: naval cutlass practice in the 19th century was of two forms. In the first, sailors (or “seamen” in the UK) drilled the general cuts and parries with real cutlasses but without contact. Forget Hollywood and novelists — no one used real swords for practice with contact, ever. Such practice spoils the edge and is likely to break blades as well, given that that the blades of sharps are not tempered for countless bending and beating as practice blades are, not to mention the inherent dangers of practicing with pointed, sharp-edged swords.

In the second, sailors exercised with practice cutlasses with leather basket hilts and wooden blades — short-bladed singlesticks in other words. The use of heavy steel blades for practice with contact, which was done for example by Hungarian sabreurs in the pre-Santelli era, requires heavily-padded fencing masks and jackets. When such protective equipment was seen shipboard, it was associated not with steel-bladed practice weapons but with singlesticks, a particularly useful practice given the sailor/seaman’s natural tendency to hit hard and hit often. Notably, neither secondary history nor period primary sources on naval cutlass drill and naval swordplay describe practice with steel-bladed practice cutlasses.

After Jim’s reply, I went through my extensive fencing library, both of real and digital volumes, then searched further online. Catalogs were an obvious source, and which quickly rewarded me, thus:

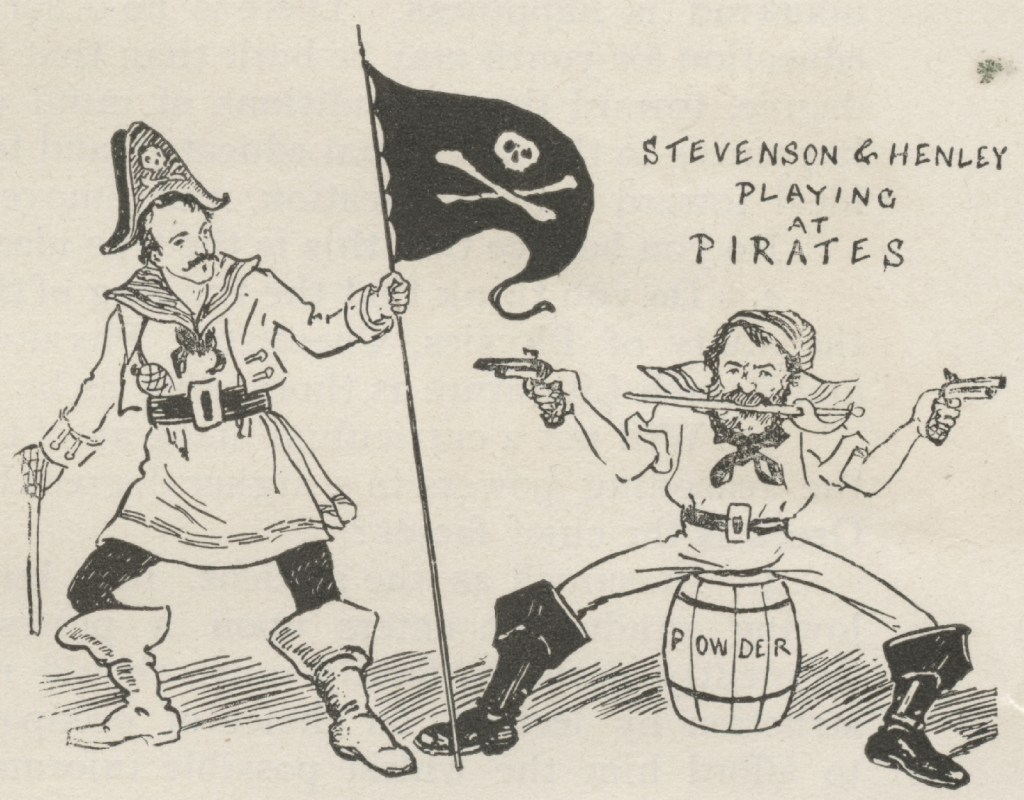

As is now obvious, my “naval practice cutlass” is in fact a theatrical sword known as a “combat sword” used, as one ad above notes, “for Theatres and Exhibitions; used on the stage all over the world.” Combat swords like these were “common theatrical properties” in the 19th century, and these swords and their stage combats were a common feature of 19th century British popular theater, particularly among the provincial theaters and touring troupes in the first half of the century, although their combats were performed throughout the century and in other theaters as well. So associated with the theater was the combat sword that Robert Louis Stevenson is holding one in the image at the top of the page. (Side note: the article that accompanies the image is about Stevenson and Henley’s new play, Admiral Guinea, in which Treasure Island villain Blind Pew features prominently.)

Charles Dickens (probably; he was at the very least the editor of the piece) gives perhaps the second best description (and also the best, farther below) of the 19th century practice of stage combat with “combat swords” in the popular theater:

“Broad-sword combats were at one time very popular interludes at minor theatres. They were often quite distinct performances, prized for their own sake, and quite irrespective of their dramatic relevancy. It cannot be said that they suggested much resemblance to actual warfare. Still they demanded of the performers skill of a peculiar kind, great physical endurance and ceaseless activity The combat-sword was an unlikely looking weapon, very short blade with a protuberant hilt of curved bars to protect the knuckles of the combatant. The orchestra supplied a strongly accentuated tune, and the swords clashed together in strict time with the music. The fight raged hither and thither about the stage, each blow and parry, thrust and guard, being a matter of strict pre-arrangement. The music was hurried or slackened accordingly as the combat became more or less furious. “On, two, three, and under; one, two, three, and over;” “robber’s cuts;” “sixes;” the encounter had an abundance of technical terms. And each performer was allowed a fair share of the feats accomplished: they took turns in executing the strangest exploits.

“Alternately they were beaten down on one knee, even lower still, till they crawled serpent-wise about the boards; they leaped into the air to avoid chopping blows at their lower members; they suddenly spun round on their heels, recovering themselves in time to guard a serious blow, aimed with too much deliberation, at some vital portion of their frames; occasionally they contrived an unexpected parry by swiftly passing the sword from the right hand to the left. Now and then they fought a kind of double combat, wielding a sword in either hand. Altogether, indeed, it was an extraordinary entertainment, which evoked thunders of applause from the audience. The eccentric agility of the combatants, the peculiarities of their method of engagement, the stirring staccato music of the band, the clashing of swords and the shower of sparks thus occasioned, were found quite irresistible by the numberless playgoers… Of late, however, the broad-sword combat has declined as a theatrical attraction, if it has not altogether expired. The art involved in its presentment is less studied, or its professors are less able than once was the case.” (Excerpted from “Alarums and Excursions” in All the Year Round, March 9, 1872, edited by Charles Dickens.)

From Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens we have a surely experience-based description of a rehearsal combat between two young actors dresses as Jack Tars and armed with combat swords. Dickens was once a young player in the “minor theatre” in Great Britain, and more than one historian considers his description of such theater in Nicholas Nickleby to be based on his own experience. Some scholars even point to specific persons who likely inspired some of the theater characters.

“Nicholas was prepared for something odd, but not for something quite so odd as the sight he encountered. At the upper end of the room, were a couple of boys, one of them very tall and the other very short, both dressed as sailors — or at least as theatrical sailors, with belts, buckles, pigtails, and pistols complete— fighting what is called in playbills a terrific combat, with two of those short broad-swords with basket hilts which are commonly used at our minor theatres. The short boy had gained a great advantage over the tall boy, who was reduced to mortal strait, and both were overlooked by a large heavy man, perched against the corner of a table, who emphatically adjured them to strike a little more fire out of the swords, and they couldn’t fail to bring the house down, on the very first night.

“‘Mr. Vincent Crummies,’ said the landlord with an air of great deference ‘This is the young gentleman.’

“Mr. Vincent Crummles received Nicholas with an inclination of the head, something between the courtesy of a Roman emperor and the nod of a pot companion; and bade the landlord shut the door and begone.

“‘There’s a picture,’ said Mr. Crummles, motioning Nicholas not to advance and spoil it. ‘The little ‘un has him; if the big’un doesn’t knock under, in three seconds, he’s a dead man. Do that again, boys.’

“The two combatants went to work afresh, and chopped away until the swords emitted a shower of sparks: to the great satisfaction of Mr. Crummles, who appeared to consider this a very great point indeed. The engagement commenced with about two hundred chops administered by the short sailor and the tall sailor alternately, without producing any particular result, until the short sailor was chopped down on one knee ; but this was nothing to him, for he worked himself about on the one knee with the assistance of his left hand, and fought most desperately until the tall sailor chopped his sword out of his grasp. Now, the inference was, that the short sailor, reduced to this extremity, would give in at once and cry quarter, but, instead of that, he all of a sudden drew a large pistol from his belt and presented it at the face of the tall sailor, who was so overcome at this (not expecting it) that he let the short sailor pick up his sword and begin again. Then, the chopping recommenced, and a variety of fancy chops were administered on both sides; such as chops dealt with the left hand, and under the leg, and over the right shoulder, and over the left; and when the short sailor made a vigorous cut at the tall sailor’s legs, which would have shaved them clean off if it had taken effect, the tall sailor jumped over the short sailor’s sword, wherefore to balance the matter, and make it all fair, the tall sailor administered the same cut and the short sailor jumped over his sword. After this, there was a good deal of dodging about, and hitching up of the inexpressibles in the absence of braces, and then the short sailor (who was the moral character evidently, for he always had the best of it) made a violent demonstration and closed with the tall sailor, who, after a few unavailing struggles, went down, and expired in great torture as the short sailor put his foot upon his breast, and bored a hole in him through and through.

“‘That’ll be a double encore if you take care, boys,’ said Mr. Crummies. ‘You had better get your wind now, and change your clothes.'”

In The Adventures of a Strolling Player, Simon Tomkins (a pseudonym) describes a comical end to Hamlet during the duel, fought not with foils or stage rapiers but with combat swords: “Not being able to procure foils Hamlet and Laertes were obliged to indulge in those deadly weapons technically known as combat swords which are greatly used by stage robbers, pirates, and British sailors. As fencing would have proved rather ineffective with these clumsy instruments and as Laertes was not au fait in that elegant accomplishment, it was judged expedient at rehearsal to change the received mode for that of a cut and thrust melodramatic description. But alas! Polonius’s son by no means justified the encomiums of the gentleman from Normandy who gave him such report for art and exercise in his defence, for he missed half the blows and when Hamlet was striking down he was usually striking up and vice versa; in brief they performed what actors call the ‘double misses.’ This excited much derision from the audience…”

“Snifkins [playing Hamlet] brought the duel to an end as quickly as possible, but when he rushed upon his father in law instead of that gentleman suffering himself to be quietly run through the body as every Claudius has from the days of Shakespeare, he presented a sword and reeling forward exclaimed ‘Come on old cock I’ll teach you to fight the round eights!’ A touch however was sufficient to destroy his equilibrium and having prostrated his arch enemy, Hamlet died as quickly as possible and the curtain descended amidst hisses and derisive laughter.”

Philip Beck provides more detail in 1883: “Time was, and not long since, when a combat generally consisted what is technically known as round eights, singles, threes, broken fives, primes (pronounced preams), double primes, and passes. Very popular was a mysterious combination known as the ‘Glasgow Tens;’ so also was another desperate encounter, carefully arranged, and called ‘The Gladiators,’ this last being a combat fought to music, each blow being struck to its accompanying note or chord in the orchestra.” (Excerpted from “Realism” by Philip Beck, in The Theatre, September 1, 1883.)

Walter Herries Pollock (“Stage Swordsmanship,” The Theatre, June 1, 1896) notes that the swordfights were fought only with the “cutting” edges, and the thrust was used only to deliver the final blow: it was “delivered between the arm and body to make an end at last of the principal villain.” There is a late but fine example of this thrust ‘twixt arm and body in the 1924 silent film Peter Pan, in which John “kills” a pirate.

Actor Frank Price in 1892 described a stage combat he had once had with Irishman George St. George, a stage name of course; the Irishman noted that he would not be hired in England under his real Irish name, so prevalent was anti-Irish sentiment. “I was playing the heavy part,” Price writes, “and in the last scene George and I had a grand sword combat, during which the air was thick with eights, fives, Glasgow tens, and occasional bad language when a stroke was missed or a shin damaged. After great excitement George, having guarded a head blow from me, was wont to kill me in the effective but mysterious manner adopted on the stage.”

A few years later Price was traveling in disguise as an Arab for safety in Egypt during the “Soudan War” (the Mahdist War, 1881-1899) when he came across a red-whiskered Arab in his path. After mangling an Arabic expression intended to determine whether the Arab before him was friend or foe and not receiving the reply he was told to expect from a friendly Arab, Price and his likely enemy drew their swords and fought, Price using all of his stage combat skill in round eights and Glasgow tens and more. But just as he forced a head parry and was about to deliver the killing stroke, his Arab adversary shouted, “Murther alive! I’m kilt!” It was George St. George, also traveling in disguise for safety. (From Frank Price, “A Grand Combat,” The Era Almanac, 1892.)

What were the “Glasgow tens” and similar patterns? The best description I’ve found so far is in Cut and Thrust: The Subtlety of the Sabre by Leon Bertrand, 1927, in which the author refers to the “Glasgow cuts”: “Hero and villain would cross swords on either side with the points raised, the blades meeting with rare swish. These manœuvres were continued, the wide sweeping cuts describing a downward course until steel met steel again. If the encounter had to be prolonged these movements were repeated in toto — and then somebody had to die. Nobody was deceived. Rather, both principals gave an idea they were sharpening each other’s blades for the Sunday joint.” One imagines a repeated series of tierces and secondes, perhaps with an occasional quinte replacing a tierce — a series often still seen in Hollywood and on stage even today. These are not exchanges of attack, parry-riposte, counter-parry-riposted, &c, but of blades flung into position and clashing against each other.

Likewise the “one, two, three, and under” and “one, two, three, and over” noted above Dickens: the former is probably a clashing of blades in tierce, seconde, tierce, then a thrust to the flank, the latter reversed, a clashing of blades in seconde, tierce, seconde, and a thrust to the torso high.

A real sword fight based on old stage combat techniques notwithstanding, Philip Beck also noted that by the late 19th century many actors were now taught conventional swordplay, even if, he writes tongue-in-cheek, it is “one, two, and third in your bosom” — probably an “un, deux, trois” (three disengages, each in the opposite direction, the first two as feints, the third “thrust home”) although it might more broadly be any two feints prior to the final, a form of attack many modern sport fencers are now, sadly, unfamiliar with except occasionally in theory or, even more rarely, as an exercise in blade control and timing, much less actually able to perform when actually fencing.

William McTurk, assistant fencing master and later fencing master at King’s College London, and Baptiste Bertrand of Salle Bertrand on Warwick Street in London led the effort to train actors in proper swordplay and may be considered the founders of the modern schools and efforts at theatrical and film swordplay in the UK although many actors on their own learned to fence in order to improve stage swordfights. J. D. Aylward in The English Fencing Master blames Captain Alfred Hutton “and his circle” for educating the public in swordplay; no longer would theatergoers be satisfied with the mere clashing of combat swords. Even so, Leon Bertrand in his 1927 Cut and Thrust: The Subtlety of the Sabre notes that the “Glasgow tens” were still seen occasionally on stage and even in some of the silent films of the day.

Above, early 19th century nautical melodrama playbills. Courtesy of the British Library.

The combat sword doubtless owes its origin to the popularity of nautical theater in which the swords were used in choreographed combats composed of Jack Tars dispatching various villains, usually pirates, bandits, and Moors. These nautical dramas — melodramatic compositions of nautical cliches and tropes extolling the vigorous virtues of British seamen — were one of the most common presentations in the popular theater of 19th century Britain, with Jack Tar its hero and the athletic combat sword-wielding, hornpipe-dancing T. P. Cooke its most famous actor. Begun during the Napoleonic wars when the British Navy prevented Bonaparte from invading and set the stage for his defeat on land, the playful entertainment struck a chord with the working and middle classes and remained popular past mid-century. Sword combats also became a routine part of burlesques during the same period.

But as the nautical melodrama and the burlesque began to fade in popularity, the combat sword found its way into other productions, even being used to represent Medieval broadswords on occasion. Pollock notes that in the late 19th century in which he wrote, “the combat-sword, alack, is dead in almost all London theaters. It survived for a time in various burlesques, at the Olympic, for instance, in Robson’s days, and later yet; and it may very likely drag on an existence is some outlying and country theaters.”

The musical rhythm of and musical accompaniment to these popular stage combats made for safe, or at least safer, choreography, and helped rouse the audience to greater and greater excitement — just as in film swordplay today. Additionally, the weight of the combat sword made for slower movements, ideal for the stage — the audience could follow them.* The basket-hilt provided good hand protection, and this is probably the reason for its design, as Dickens noted, and not to emulate the rare true basket-hilt cutlass.

On the other hand, as I’ve pointed out in my post on Buccaneer Cutlasses, even a dull cutlass can split skin, break bones, and put eyes out, and any error in choreography could result in serious and possibly fatal injury. Thus the typical timing of the combats to musical accompaniment with a regular beat. No irregular rhythms here even though they’re ideally suited to real combat. It bears repeating: stage combat is not simply an imitation of real combat without real hits. (For further information on stage/film sword combat, see The Duel on the Beach in Captain Blood and The Duel on the Beach in Film.)

The gold tint present on many examples of combat swords was probably applied to make the blades stand out more to the audience. It was often noted how difficult it was for swordplay to stand out on the often poorly-lighted 19th century stage. Between the poor general lighting and the bright footlights, it could be difficult to follow blade movement unless the blades were broad and, as we see here, brightened with gold tint or paint. At the end of the century Pollock noted the difficulty of seeing foils on stage, and that that larger hilts were developed and attached to thicker blades so that the audience could better follow the swordplay, a practice that continued well into the development of cinema — thus the anachronistic rapier hilts with epee blades used in Captain Blood (1935), for example.

This practice of tinting or painting may have been applied to other swords used on the stage as well, particularly the narrow quadrangular foils that began to replace the combat sword in the latter half of the 19th century. On one of my walls are two fully functional foils, each more than a century old. One has a decorative figure eight guard, the other an etched round guard and etched blade. These are not Toledo wall hangers, but foils that could be used for fencing and indeed were, based on the nicks on blades and guards. Curiously and importantly, the blades of both have remains of gold tinting or paint, very similar in color and tone to the combat sword, leading me to believe that these are not, as I had first assumed, presentation foils, perhaps given as awards for fencing victory or service, but are in fact stage weapons — exactly the sort that begin to replace the combat sword when William McTurk and his contemporaries and their heirs began instructing actors in legitimate swordplay adapted for the stage.

Occasionally an astute arms seller or observer posting on the Internet points out that the iron-hilted, steel-bladed purported naval practice cutlasses under discussion are absolutely not such at all, but are “gymnastics” or “gymnasium” weapons used, obviously, in gymnasiums. The first point is entirely correct, and the second is correct after a fashion too, but they miss the swords’ actual or at least original use. So, were these stated “combat swords” ever used in gyms? It seems certain. First, they are ideal for individual practice, not only in cuts and parries but also for strengthening hand and forearm — I much prefer mine for solo practice rather than a replica wood singlestick cutlass.

Second, most examples found today are in excellent condition, with few if any nicks, indicating that they were not used on the stage or for any form of blade-to-blade contact. Third, there is occasional evidence that some surely did make their way into gyms. For example, regarding various existing exercise equipment in a military gym, “To these soon will be added the discus and bar bells, leaping pole, foils, combat swords; masks and gloves; and this is a complete a gymnasium as may be found in or out of the Army.” (Excerpted from “A Military Gymnasium,” Army and Navy Journal, 19 April 1884, bold italics mine.) I suspect that the majority sold in the late 19th and early 20th centuries ended up in gymnastic, not stage, use.

So, should these sword be considered of value to collectors? Of course! Their 19th century stage combats were as popular as any of our favorite film sword combats today, and their swords were as functional and historical as the foils, epees, and sabers used then for sport and for preparing for duels or battlefield combat. And, if used by a famous actor, combat and other stage swords were just as popular and just as expensive as any film sword today that was once used by Errol Flynn or in Star Wars. Who for example might not wish to own one of these or even the Hollywood foils used by Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland for Captain Blood publicity stills? In 1876 The Illustrated Sporting New Yorker noted that a drama editor in the city had purchased the sword used by famous actor George Frederick Cooke (no relation to T. P. Cooke) in the final act of Richard III during his notable American tour in the early 19th century. The writer notes tongue-in-cheek that the sword is the forty-ninth “original Cooke” combat sword now on display.

If the combat sword was good enough for Charles Dickens who gave us a pirate with “the one eye and the patch across the nose” in The Perils of Certain English Prisoners and Robert Louis Stevenson who gave us swashbucklers galore, it’s good enough for armchair, stage, and real swashbucklers anywhere!

Copyright Benerson Little 2025. First published 19 August 2025. Last updated on November 18, 2025.

* Heavier weapons are not only easier for an audience to follow, but also for directors and judges, or as they’re called today, referees and judges (the latter are seldom used anymore in modern fencing), to follow. Some years ago my close friend, also my former fencing master, Dr. Eugene Hamori, a Hungarian by birth, along with a Polish fellow Olympic medalist, proposed to the FIE to fix the numerous issues with modern saber by using heavier sabers of roughly 16 ounces — a mere return to the one to one-and-a-half pound weight of sport sabers in the 1920s and 30s. The proposal was ignored: the status quo will have nothing but the status quo — to keep fencing in the Olympic Games no matter the cost, no matter the degree of change from true swordplay to sport nonsense — and modern fencing will continue its decline into pure sport rather than the sport version of martial combat with swords.