Each medium–the written word, the illustration, the motion picture–has a unique ability to convey action. A novel can not only describe but explain swordplay in action; an illustration can bring a moment in time to life and make an entire action timeless; a motion picture can show action as it unfolds and as we might see it were it real.

Of all three, by turning the written description or static illustration into moving action, film may have left us with our most indelible memories and tropes of the duel on the beach. Or so I argue tenuously, for several written descriptions and illustrations come to mind that likewise bring forth indelible memories.

With fiction we must imagine the duel, even when when well-described (but almost always imperfectly nonetheless) and accompanied by the paintings of Howard Pyle or N. C. Wyeth. Written descriptions may suggest extraordinary action, yet even if it’s described accurately and in detail it’s likely that only those who’ve studied swordplay can picture it well in their mind’s eye. Written explanations almost always slow the action down, providing a false tempo and, in the worst cases, a distraction.

Accompanying illustrations can only suggest action. But don’t get me wrong! Often a written description or a painting is far more evocative than a poorly choreographed film duel.

But in film we get to see the duelists move before our eyes. They lunge, parry, and riposte. They plot and execute, they snarl and rejoice. They are living swords actively arrayed in combat before us. And they are often even more dangerously and joyfully inspiring than their descriptions in fiction or accompanying paintings!

This is part three of a five-part series on the duel on the beach in fiction and film. Part one discusses the duel on the beach in fiction, part two the duel in The Black Swan by Rafael Sabatini, part four the duel in the 1935 film version of Captain Blood, and part five the duel in reality. It’s worth reading the first two before this post, but this isn’t absolutely necessary. In this post we’ll take a look at an overview of the duel on the beach in film, with some commentary as well on film duel choreography and especially on one vital aspect of it and all swordplay: tempo.

Actors as Fencers

The actual filming of a duel can take days, and the preparation is typically extensive, beginning with a detailed written play followed by, usually, exhaustive rehearsal. I’ll provide more details on this process in the Golden Age of Film in part four, and look at actors as fencers and at tempo here instead.

Only rarely are actors actually also skilled fencers. From the Golden Age of Film just two come to mind: Cornell Wilde, a Hungarian-born US national saber champion and Olympic qualifier who just prior to the Olympic Games gave up competitive fencing for the theater and soon film, and Basil Rathbone, a studious British amateur who enjoyed swordplay and studied for five years under famous film fencing master Ralph Cavens, after having studied under famous fencing masters Félix Gravé and Léon Bertrand in the UK.

Others have managed to look the part well, with actual skill ranging from none to a little, including Danny Kaye in The Court Jester and Gene Kelly in The Three Musketeers. It surely helped that both were dancers, although for real swordplay, as opposed to choreographed, re-enacted, or fake, it helps even more to be able to sense tempo or rhythm and then break it, by which means one may steal distance and time on one’s adversary, setting him or her up to be hit at the precise moment he or she is least prepared.

I’ve had students who were both excellent dancers and excellent fencers, but also those who were excellent dancers but awful fencers, entirely unable to do anything but follow their adversary’s rhythm or a simple rhythm of their own, to their great peril. A number of them could only imitate, not tactically improvise. And to be fair, I’ve had some students who were excellent fencers but awful dancers, unable to keep to a rhythm for more than a few beats–they had long been taught not to. (I’ve even been accused of this.) They could easily sense the rhythm but only with effort could they maintain it, for by training, even instinct, they wanted to break it.

Errol Flynn, famous alongside Douglas Fairbanks as the most swashbuckling of film swashbucklers, admitted in his autobiography My Wicked Wicked Ways that he was no swordsman:

“I don’t know much about fencing, but I know how to make it look good. You only have to stand still and look forward, your head proud, and let the sword point straight out, you and the sword both unmoving, and it is dramatic. Let the sword point dip two inches, and the gesture can look very clever and dangerous.”

Our five-year-old has already, quite naturally, mastered this en garde. An old school epeeist, close friend of mine, retired (and notable) Byzantine iconographer, and portrait artist at present, Elias Katsaros,* still uses this en garde, often with the point dropped a couple inches as Flynn described; it’s highly effective for him and although approaching eighty years old, he can still give elite fencers fits with his old school dueling style of epee fencing. Flynn’s comment reflects the following description by William Higford in his book Institutions: Or, Advice to His Grandson, 1658:

“The bravest gentlemen of arms, which I have seen, were Sir Charles Candis, and the now Marquis of Newcastle, his son, Sir Kenelm Digby, and Sir Lewis Dives, whom I have seen compose their whole bodies in such a posture, that they seemed to be a fort impregnable.”

At the opposite extreme is the admonition of Dr. Eugene Hamori, my fencing master of many decades: in the en garde one should appear as if always in motion, always attacking, at all times. It goes without saying that one can appear simultaneously as both a fort impregnable and constantly on the attack. But I digress.

The reality is that, then and now, most actors were not fencers but imitators who followed a carefully choreographed routine. This is vital not only for the logistics of filming but for safety too.

Fencing Tempo: Reality Versus Cinema

If there’s one aspect of cinematic duels that often drives me crazy, it’s the obvious overuse of what might best be termed the “false tempo of choreography” in film swordplay. Some background first, so please bear with me. If you find this too technical or tedious, you can just skip straight to the films themselves.

Classical tempo, or, more accurately, true tempo, sometimes called timing, is the most vital of all aspects of swordplay. Every fencing master has his or her own definition, but basically it can be defined as the most opportune time to make a fencing action, usually an offensive one–that is, the moment when my opponent is for a brief moment helpless–without my also getting hit. False tempo or false time is any other tempo. Not getting hit means exactly that: not getting hit at all. Hits excluded by the rules of fencing or by the timing of a scoring machine would still be hits if the swords were real.

Fencing tempo may be divided into physical and psychological tempo, the latter consisting of moments of inattention, over-attention, or distraction, either by the adversary’s own action, or induced–“putting the opponent to sleep” for example–in him or her. Closely associated with tempo is cadence or rhythm.

Zoltan Beke and Jozsef Polgar’s definition of fencing tempo in The Methodology of Sabre Fencing (Budapest: Corvina, 1963) is one of the best I’ve read and is what I was taught, far more often unconsciously through lessons than consciously through lecture, by both of my Hungarian masters:

“In fencing, under the concept of tempo we include that suitable moment, at which the opponent is helpless against our fencing action. It is not enough just to recognize the moment which favours the surprising of our opponent, it must be felt. Seeing in itself is not enough, because by the time we perceive it and make our decision to act, the actual moment may have passed or the position of the opponent may have changed to our disadvantage. // In practice, we also interpret tempo as a unit of time [one cadence, or one unit of fencing time]… // In the instruction of tempo attention should be devoted to both these interpretations.”

Physical tempo is often divided into hand tempo and foot tempo, particularly in the early stages of instruction. For example, a very simple instance of hand tempo: my adversary moves hand and sword laterally from the sixte position outside to the quart position inside. Anticipating this, I attack with a disengage into the opening sixte line at the moment the hand and sword begin to move, so that my point lands as my opponent’s hand and sword arrive in the quarte position. If I wait until my adversary’s hand and sword are in the quarte position to attack, he or she has the tempo–a full cadence–in which to defend against my attack. Or, I make a simple attack as my opponent starts to lower their hand, opening the line. Again, I don’t wait until the line is entirely open.

Similarly foot tempo. The Hungarians, for example, define three major forms: the attack on preparation (attacking as the adversary advances in preparation), the accelerating attack (attacking as the adversary fails to retreat or retreats too slowly), and the “taken over” attack (attacking on the adversary’s recovery from a failed attack). In the first, I attack when my adversary begins his or her advance, because for a moment there is nowhere to go while the foot is in the air. The opponent is temporarily helpless to escape. Further, if my adversary is preparing an attack, they may be over-focused on it, providing me with psychological tempo in addition. They’re distracted, in other words, by their preparation. Or I can attack with an accelerating movement (usually an advance-lunge) if my adversary fails to retreat as I advance, or retreats too slowly. Again, for a brief moment my opponent is helpless to escape. Or, I can attack during my adversary’s recovery from an attack, for here psychological tempo also plays a significant role–the recovering adversary is not only typically slower than the attacker, but they tend to believe they are safer during the recovery than at the exact moment the attack has failed, and tend to let their guard down, particularly if their opponent has not previously attacked during recovery.

In practice, hand and foot tempo go–forgive me–hand-in-hand. One must time them both, although often one or the other predominates. For example, I may have superior blade-work against a particular adversary, leaving me to concentrate largely on finding the foot tempo with which to make the attack, and vice versa.

In sum, I want to attack in anticipation of my adversary’s movements, keeping a full cadence ahead, resulting in his or her inability to defend in time. Again, vitally, this tempo must also aid in protecting me so I don’t also get hit, and leave me in position to recover quickly or secure my adversary’s sword so I’m not hit immediately afterward (Sir Wm. Hope called such “double” hits exchanged hits).

True fencing tempo is not the tempo of a game of tag!

But there are other forms of tempo, the rules of each weapon creating them. Although classical or true tempo still applies to a degree, modern foil and saber are also governed by an artificial or false tempo of convention, also known as “right of way” rules, in theory derived from reality and true tempo but in practice suicidal, given that (1) they permit the attacker to disregard counter-attacks into the first tempo, and (2) they now permit attacks in invitation (with the sword in a non-threatening position, that is), bot of which with a real sword would often result in impalement.

In modern epee, the timing of the scoring machine creates a false tempo that often takes priority over true tempo, turning it into a game of “hit at least a 20th to 25th of a second before getting hit,” rather than “hit and not get hit.” Often the majority of epee touches would be double hits were the weapons real. In electrical epee’s defense, the early rules of epee tempo, when judged by the eye, not the machine, were found to be difficult to maintain, and so judging was simplified: a hit arriving noticeably before the other was counted. The electrical apparatus simply made this easier to judge. (Note that the timing of the box — touches within a 20th to a 25th of a second of each other are counted as a double, and a touch that lands later than this after another is not counted — replicates the smallest difference in time in which most people’s perception can distinguish between two touches, although having a small range, a 20th to a 25th of a second in this case, is actually necessary for the apparatus to operate correctly.)

Again, although true tempo still plays an important role in all three weapons, it is often, unfortunately, overshadowed or even superseded by the tempos created by the rules governing the weapon.

This has long been a problem even in the days in which swords were worn and duels were fought: “…because whoever will be but at the Trouble to visit the Fencing-schools, shall scarcely see one Assault of ten, made either by Artists against Artists, or Artists against Ignorants, but what is so Composed and made up of Contre-temps [double touches resulting from an attack into an attack, or from simultaneous attacks], that one would think the greatest Art they learn, and aime at, is to strive who shall Contre-temps oftnest…” (Sir William Hope, The Sword-Man’s Vade-Mecum, 1694.) Even three centuries ago, fencers in schools tended toward tag rather than true tempo. If you want to experience Hope’s frustration today, watch any competitive bout in modern fencing, classical fencing, or HEMA (Historical European Martial Arts). The natural tendency to turn all forms of fencing into a game of “hit first” tag is difficult to suppress.

There is also the false tempo of the fencing master whose goal is to get hit, unlike the fencer whose goal ideally is to not get hit. The fencing master, in other words, provides opportunities for the student to hit: he or she uses false tempo–often via exaggeration, hesitation, other error, or all of these–to train true tempo. (But he or she also uses true tempo when necessary, for example to surprise a student making a repeated error.) As an old friend, an outstanding foilist in his youth, an outstanding epeeist later, now also a retired French army colonel, put it when he first met me: “I love to fence fencing masters and teachers, they always fence like they’re giving a lesson: they hesitate and I hit them!” He was quite correct. Even so, he never won more than half his bouts against me, in spite of my teaching handicap, for the tendency to hesitate can, with practice, be suppressed, not to mention that friendly competitive Gallic arrogance can motivate an opponent. I fenced some of my favorite bouts against him.

Last, we have the false tempo of film fencing choreography, best described by famed film fencing master Fred Cavens:

“For the screen, in order to be well photographed and also grasped by the audience, all swordplay should be so telegraphed with emphases that the audience will see what’s coming.” (Fred Cavens quoted in “Swordplay on the Screen” by film historian and film swordplay commentator Rudy Behlmer in Films in Review, June-July 1965.)

But if the audience can see it coming, so in reality can the adversary, and far more easily!

At its best, with great action and editing, this false tempo of choreography is less noticeable. At other times it is awful and drives fencers like me crazy as we spot numerous opportunities in which we would have attacked or defended had we been in the duel ourselves. Worse, the clearly weaker fencer often wins per the script (watch The Spanish Main, for example). In such choreography’s defense, much of this has to do with safety, the lack of skill of many actors (although the unskilled were often doubled as much as possible), and as Cavens noted, to help the audience understand what’s going on.

Even so, film swordplay can be exciting without resorting to this false tempo–but this takes skilled actors, skilled fight choreographers, and skilled editors, not to mention willing directors. In most cases these days, in spite of a fair number of capable fight directors, film swordplay is of the “hack and slash, make it look rock and roll” variety. Trite and lazy, in other words, if exciting at times to the uninitiated.

Or, as one well-experienced Hollywood stuntman, swordsman, and film swordplay choreographer put it, “You do what the director wants, however ridiculous, or you get fired.” Fred Cavens once walked off the set after a director insisted on filming a swordfight with one of the actors standing on a table: in reality, the swordsman would be unable to defend himself adequately from adversaries cutting and thrusting at his feet and legs. Sometimes even Hollywood antics are too much.

Most directors these days don’t seem to care about exciting, accurate swordplay. Even so, we can hope and dream, and enjoy those few films that do still occasionally elevate swordplay to the degree those of us who follow the sword desire.

Now to the film duels on the beach!

To Have and to Hold, 1922

Based on the novel by Mary Johnston, a writer who had significant influence on Rafael Sabatini, this 1922 Paramount version is lost as is the 1916 Paramount version. Remakes were as common then as now–why not beat a dead horse if it’s profitable? We have no cinematic details on the duel on the beach in either version to my knowledge.

This fictional duel is perhaps best-known today for Howard Pyle’s painting of the duel for command in the novel, between gentleman hero and the last of three pirate villains he fights one after the other, on what is known today as Fisherman’s Island off Cape Charles, Virginia. Clearly, the duel was filmed somewhere on the California coast rather than upon a flat Virginia islet. Santa Catalina Island is often considered the likely suspect location, but such scenes were more often filmed on the California coast itself or even on studio sets. See The Duel on the Beach, Part I for more general details, including paintings by Howard Pyle and Frank Schoonover.

Captain Blood, 1924

Several years prior to 1924, Douglas Fairbanks–actor, director, writer, producer (auteur in other words)–had already established the swashbuckling film genre as we know it today (and usually poorly imitated now) in The Three Musketeers and The Mark of Zorro. Film permitted him to carry swashbuckling adventure beyond the constraints of reality. His swashbuckling heroes could fight and defeat a half dozen or more enemies at once, climb buildings and do stunts like Jackie Chan before Mr. Chan was born, and swing from every chandelier in sight.

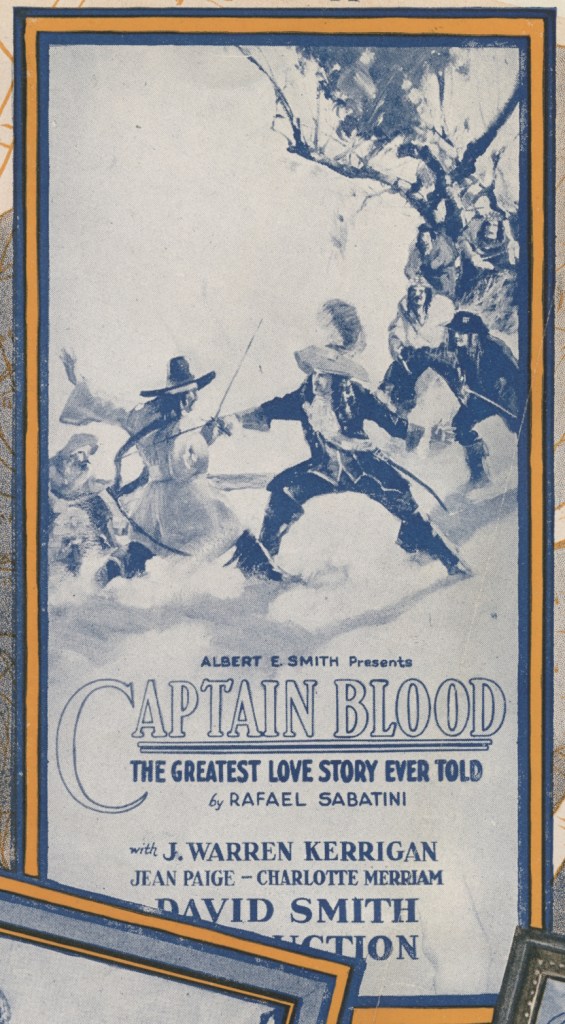

But he had yet to make a pirate film. In 1924, Vitagraph produced Captain Blood based on the novel by Rafael Sabatini, a mere two years after the book’s publication, and beating Fairbanks by two years to his own pirate film. The movie was intended to be, and was, everything we’ve come expect of a blockbuster even if it’s star, J. Warren Kerrigan, had once said the following to a Denver Times reporter in 1917:

“I am not going to war. I will go, of course, if my country needs me, but I think that first they should take the great mass of men who aren’t good for anything else, or are only good for the lower grades of work. Actors, musicians, great writers, artists of every kind—isn’t it a pity when people are sacrificed who are capable of such things—of adding to the beauty of the world.”

No real Captain Blood he, clearly, nor anything resembling an honorable person, but then, actors, with some notable exceptions, are for the most part actors imitating heroes, not heroes playing heroes. Still, we expect more even from actors.

Unfortunately, only thirty minutes of the original film survive, and the duel footage is not found among them. In the image above, note the Howard Pyle-inspired arrangement of duelists and spectating pirates. Beyond this, we’re left now to our imaginations.

Historically-speaking, such duelists may have stripped off coats, sword-belts or baldrics, and, in the case of Peter Blood, periwig if he were still wearing one (he appears to have switched to his own hair by now), for which we have historical evidence, although not all swordsmen stripped down. Whether they did or did not depended largely on the circumstances of the fight and personal inclination. In the novel, there is no indication but that the two men fought as they were dressed, given the hasty development of the rencontre and drawn swords.

In fact, lighter dress was the norm in the tropical climate: a scarf instead of a periwig and a waistcoat but no coat over it, except on the most formal of occasions. And no boots, except on horseback, even if Rafael Sabatini permitted them on sandy, dune-ridden dueling shores. 🙂

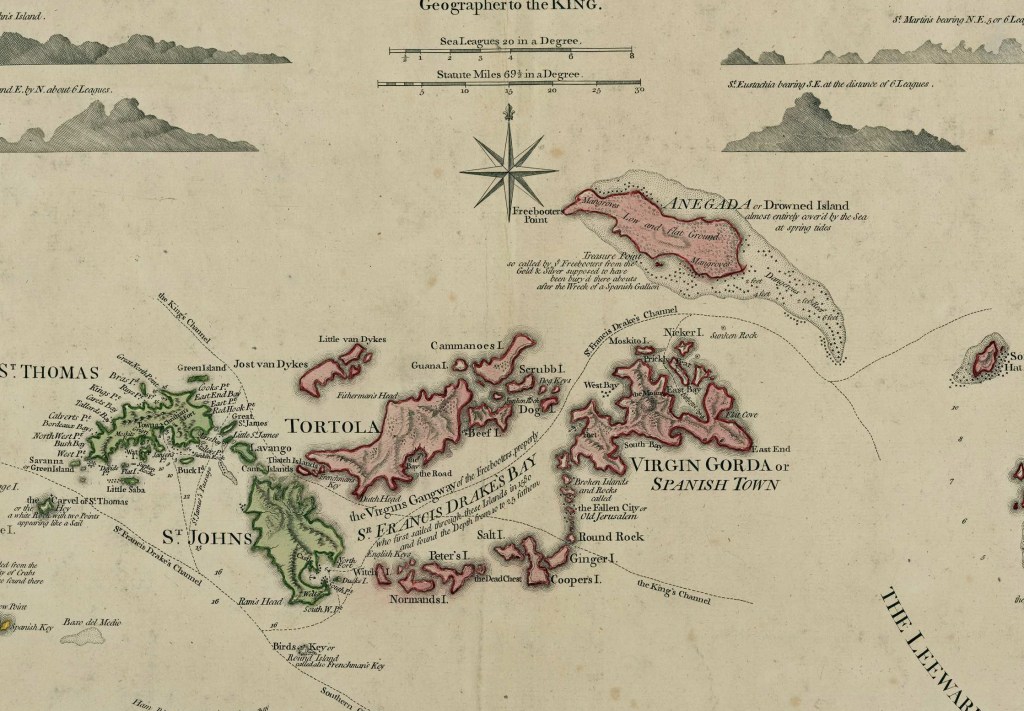

In the novel, the duel was fought on Virgin Magra, Sabatini’s joke on Virgin Gorda–the island isn’t actually fat but more or less skinny, depending I suppose on your perspective. There are one or two possible beaches on Virgin Gorda where the duel, as described in the novel, could have been fought, but more on this in part four when I discuss the 1935 film version in detail in part four.

Clothes Make the Pirate, 1925

A comic film starring Leon Errol and Dorothy Gish, based on the comic pirate novel by Holman Day of the same name, the duel is merely a pretend one between two tailors masquerading as pirates, one of them named Tidd who is pretending to be the famous pirate Dixie Bull. The film no longer exists, unfortunately, and there are no stills of the duel, at least not that I’m aware of. The image above is from the photoplay edition, and depicts the final confrontation between the fake Bull and the real, with the fake triumphing, of course. After all, it’s a comic novel.

The Black Pirate, 1926

Released in 1926, The Black Pirate starring Douglas Fairbanks set the parameters and even more importantly, the expectations, for one of the three major forms of the swashbuckling pirate genre for the next century: the semi-historical pirate romance-adventure in traditional form, of which Captain Blood and The Sea Hawk are the finest examples; the semi-historical or “sort of historical” pirate adventure, any of the versions of Treasure Island for example, and the television series The Buccaneer and Black Sails (full disclosure: I was the historical consultant on Black Sails); and the purely pirate fantasy, usually with a bit of romance on the side, filled with pirate myth and trope, of which The Black Pirate is the original, and still the finest, example, although honorable mention goes to The Crimson Pirate and perhaps–and only perhaps–the first of the Disney pirate films.

The Disney pirate films carry the pirate fantasy to extreme with occult and mythological nonsense, if entertaining at times. Many pirate films, particularly the generally inferior B versions, straddle the genres between romance-adventure and pirate trope and caricature, generally leaning more on the latter. Except for some of the pirate historical romance adventures such as Captain Blood, all have been more or less, usually unsuccessfully, based on the genre formulated by The Black Pirate. Even the Disney pirate films owe not only their origin but their Peter Pan fantasy and tongue-in-cheek atmosphere to this Douglas Fairbanks film.

By his own admission Fairbanks was inspired as much by Peter Pan (thus Fairbanks’s costume) and Howard Pyle’s paintings as by Alexander Exquemelin’s buccaneers, making The Black Pirate is a straightforward pirate fantasy adventure marked by the swashbuckling derring-do of Fairbanks himself. And it’s entirely enjoyable because it doesn’t pretend to be anything else.

The swordplay is the film reflects the genre Fairbanks was creating, or rather, reflected the style of swordplay Fairbanks had already designed and set in motion in The Three Musketeers:

“For here, plainly, is a D’Artagnan that not even Dumas ever dreamed of. He is the personification of all the dashing and slashing men of Gascony that ever fought their way through French novels, all for the smile of a lady. He never fences one man if there are six to fence instead, he never leaves a room by the door if there is a window or a roof handy, he never walks around any object (including human beings) if he can jump over them; he scales walls at a bound, carries prostrate damsels over roofs, hurls men one upon another, rides no horse save at a gallop, responds to the call gallantry at the drop of a hat, and general makes himself an incomparable D’Artagnan.” (New York Times review of The Three Musketeers, August 29, 1921.)

The duel on the beach between the pirate captain (Anders Randolf) and the shipwrecked Duke of Arnoldo (Fairbanks), bent on avenging the death of his father was choreographed by Fred Cavens rather than Fairbanks’s usual Belgian master H.J. Utterhore (Henri Joseph Uyttenhove). Cavens ultimately choreographed the swordplay in more than fifty films by my count; Thomas Brady in “Meet Hollywood’s Fencing Master” (New York Times, October 5, 1941) noted seventy-five as of the date of his article.

Fairbanks’s character is a revenge-seeking, pirate-hunting Spaniard who comes to be known as the Black Pirate, so cup-hilt rapier and parrying dagger are appropriate arms. However, it’s unlikely the real pirate captain would himself have carried these weapons. But no matter–it’s fantasy entertainment after all.

The duel setup is a classic one derived from pirate myth, particularly as depicted in To Have and to Hold by Mary Johnston, a novel illustrated by Howard Pyle and influential in the writing of Rafael Sabatini: a man wishing to join a pirate crew proves himself by fighting a duel with the best swordsman (or swordsmen, in the case of Johnston’s novel), and it seems that the pirate captain is always the best or one of the best. Pyle’s illustration (see part one) clearly influenced the film duel’s arrangement.

The 25 cent oversized film program–$3.64 in present dollars which was quite a good deal actually, given that most similar programs typically cost $10 to $20 today, the modern practice of gouging fans being what it is–was written, illustrated, and published in the style of a Howard Pyle, Charles Johnson, or Alexandre Exquemelin sea roving journal (or all three!). At one point it describes the duel with lines by its pretended pirate-author “Sandy MacTavish” (actually screenwriter Lotta Woods who wrote several screenplays for Douglas Fairbanks but not The Black Pirate), of which the following are examples:

“Another step backward and the Captain was in the lagoon, while the stranger, with punctilious ceremony, waited for his recovery. The Captain was like to burst a blood-vessel. He scrambled to the bank and made a powerful thrust that backed the stranger toward the line of our men.”

However, in spite of the Black Pirate’s “punctilious ceremony,” he ends the duel by causing the pirate captain to trip and fall backwards onto the point of a parrying dagger the Black Pirate had placed there beforehand just for the purpose and somehow entirely unnoticed by the entire pirate crew.

According to Tracey Goessel writing for the National Film Preservation Board at the Library of Congress, Anders Randolph’s rapier cut Fairbanks’s arm during filming, causing the swashbuckling star to curse. She also notes that he was injured again, this time when fencing with Fred Cavens who was standing in for Randolph. A cut close to the eye was a result, but guests were present, so Fairbanks smiled and said, “Pirates always were a bloody lot.”

The duel is magnificently choreographed, easily one of the most exciting of any Hollywood film and one that certainly ties with 1935 Captain Blood duel (also choreographed by Cavens) as the best of any pirate movie. Although there are numerous Hollywood flourishes, the swordfight comes across as realistic. Given the speed of the actions and the technique involved, it’s easy to see how Fairbanks was injured.

Of course, the less-than-honorable and probably impractical-except-in-film trick of fence is arguably entirely permissible when a pirate is the adversary, not to mention when the adversary is the man who murdered your father long before (in cinematic years) Inigo Montoya sought similar revenge:

“As if a man that lies at the mercy of common Pirates [praedonibus: of the robbers or plunderers], should promise them a certain Sum of Money for the saving of his Life: ‘Tis no deceit to recede from it, tho’ he had given his Oath for the performance: for we are not to look upon Pirates [pirata] as Open and Lawful Enemies: but as the Common Adversaries of Mankind [communis hostis omnium]. For they are a sort of men with whom we ought to have neither Faith, nor Oath in common.” (Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Officiis 3:29.107, in 44 BC. Translated by R. l’Estrange, 1720.)

Although the story is entirely fictional, we can do a little sleuthing and intelligently imagine where the duel might have taken place. Given that the tale in set in the “Southern Seas,” we know that this is the South Sea, aka the Pacific coast of the Spanish Main, and probably takes place in the 1680s when most of the great South Sea buccaneer expeditions took place.

Looking at the map in the film program, there is only one area that orients this way: the Isthmus of Darien. Therefore Panama, and therefore Isla Chepillo would be the prime candidate. It’s even shaped a bit like the island on the pirate chart! It’s not a perfect fit, but no matter: Panama and Chepillo will serve, and there are plenty of “pirate coves” to the west.

Chepillo, however, was not entirely a desert isle, making buried treasure a bit more difficult. That said, given that buried pirate treasure is a myth, we can just as easily fantasize that the island was uninhabited, or that the inhabitants were unlikely to find the treasure.

In fact, true desert isles were hard to find even in the seventeenth century. Most islands, even small ones, had inhabitants, and the rest, if they had any resources at all, were visited from time to time. In 1681, English buccaneers landed on Chepillo and took aboard good fresh water, plantains, two fat hogs–and fourteen black and mulatto prisoners. Whether free or enslaved, the buccaneers would doubtless have kept them as slaves.

Captain Blood, 1935

Not only my favorite of all film duels, and not just of those on the beach or in pirate films, but also one of the best to watch and enjoy. So notable and influential is it to the film swordplay that followed that I’m not going to discuss it here, but in this blog post! My apologies to anyone (temporarily) disappointed; just follow the link after you finish this post!

The Little Savage, 1959

Not a duel per se, but an affray, rencontre, or simple swordfight on the beach between the now-adult “Little Savage” castaway and a pirate. The little savage slips (avoids with blade and body) an “inside” aka a cut or slash in quarte, then thrusts to the belly, ending the fight. Purists might suggest a hard cut to the arm, neck, or head might’ve been appropriate, but let the fighter (or in this case, choreographer) choose his or her stroke. Nicely done, if too brief. The film is based on the Frederick Marryat novel of the same name, with a fair number of liberties, including Spanish pirates with Disney Treasure Island tropes.

The Queen of the Pirates (La Venere dei Pirati), 1960

An Italian pirate film dubbed into English, starring Gianna Maria Canale, queen of Italian costume films, as Sandra, who with her father flees to sea to escape a false accusation and, naturally, become pirates. The film has plenty of pirate tropes, and two years later Canale would reprise her role as a pirate queen in The Tiger of the Seven Seas. She wields a rapier quite well and quite aggressively, if Hollywood-style, in both films, including in a tavern duel in the latter. Coming from a family of circus performers, she has an obvious athletic grace.

In fact, I am impressed with her swordplay, having previously only seen Maureen O’Hara, Binnie Barnes, and Jean Peters of this era swashbuckle well sword-in-hand. Canale compares well with these three film swordswomen and might be fiercer than all three, including even Peters.

In the film, Sandra and another pirate captain agree to settle their differences “con la punta de la spada,” which happens to be represented by cup-hilt rapiers. Assuming the pirates are intended to be Italian as described in the film’s description, the swords are then for once appropriate: cup-hilt rapiers were common in Spanish-held regions of Italy in the 17th century. I’m unsure what century the film is actually set in, though: the film advertising pretends the 16th, but the pirates look quite 17th century Hollywood Caribbean.

What follows is, if too short, a respectable if theatrical film duel with single rapiers that ends in Sandra disarming the other pirate captain with a disarm that actually can work in real fencing, at which point they laugh and make friends again. Canale displays some tight technique, including quick disengages against attempted beats and binds. Unfortunately, given the duel’s short length, there isn’t much opportunity for movement across a wide setting. The movie was filmed on location on the shores of Tuscany, although the sea settings were intended to represent the Adriatic on the eastern coast of Italy. The film’s “master of arms” was fencing master, actor, and stunt performer Franco Fantasia. See also Rage of the Buccaneers below.

Morgan the Pirate, 1961

Starring pre-Schwarzenegger muscleman Steve Reeves as Henry Morgan, and a largely Italian cast dubbed into English (there are several “Spaghetti pirate” films in fact), the film is reasonably watchable if you’re a kid with nothing else to do on a Saturday afternoon. It has most of the usual tropes: escaped servant-slaves, sea fights, shore fights, forts, evil Spaniards, Conquistador armor, cup-hilt rapiers, “exotic” women, &c. The color is lavish and the settings beautifully tropical.

And the duel? The usual Hollywood hack-and-slash filmed on an Italian beach (Procida Island off Naples, I believe) standing in for Basse Terre, Tortuga, with backgrounds clearly influenced by the paintings of Howard Pyle: ships at anchor, pirates watching in rapt attention, and palm trees.

The swordfight, Henry Morgan versus François l’Olonnais, begins in a tavern (another film duel trope possibly due a blog post), fought in triplicate over a desire to join the buccaneers, a need for supplies, and the protection of women. At first, l’Olonnais intends it to be a fight with daggers, clearly inspired by the famous Howard Pyle painting. However, upon seeing Morgan’s muscles, he chooses swords–cup-hilt rapiers, of course, even if historically incorrect–instead. Still, Reeves’s bulk was a lot of target for a knife, and l’Olonnais might have used Butch Cassidy’s technique in addition. But no matter, swords it is because by now the duel on the beach with rapiers is a trope.

The duel continues outside in Captain Blood versus Levasseur (1935, of course) style up and down the shore and dunes. But it’s nowhere near as well-choreographed or filmed as the famous 1935 film fight, even if it has a moment or two.

Mostly, it seems a set piece intended primarily to showcase Reeves’s muscles. In fact, it wouldn’t be out of place in a beach party film of the era, at least as a fantasy dream scene, if a bit serious. What swordplay Reeve’s seems to know appears to have been picked up while rehearsing fights in some of the “Sword and Sandal” films he starred in. The duel ends when Reeve, clearly the underdog in swordplay, throws away his rapier, grapples with l’Olonnais, and disarms him.

The swordplay was choreographed by famous Italian fencing master Enzo Musumeci Greco, of the even more famous Aurelio and Agesilao Greco family of fencers dating to the mid-19th century. The two just-mentioned Greco brothers highly influenced the Italian form of epee fencing for both dueling and sport. Time to train students and student aptitude limit even the best of masters (not to mention being limited by a film director’s “vision”) so I certainly don’t blame Maestro Greco for the inauthentic nature of the swordplay in Morgan the Pirate.

Greco also worked with Errol Flynn in Crossed Swords, with much better swordplay, and Burt Lancaster in The Crimson Pirate, which really didn’t have much in the way of swordplay although the fencing-with-fish bit is enjoyable. The Greco Academy of Arms in Rome still exists and still trains world class fencers. It also has a nationally-recognized fencing museum, the Casa Museo Accademia d’Armi Musumeci Greco that I’ve been told is well worth visiting.

To my knowledge, the soundtrack by Franco Mannino, including the track accompanying the duel, has never been released.

Rage of the Buccaneers (Gordon, il Pirata Nero), 1961

Also released as Gordon, the Black Pirate; The Black Buccaneer; The Black Pirate; Gordon, the Knight of the Seas; Pirate Warrior; and possibly other names if I’m not mistaken, the film stars Ricardo Montalbán as former slave and now pirate captain Gordon, and Vincent Price as Romero, a wealthy slave trader. It’s another “Spaghetti pirate” movie with a largely Italian cast dubbed for UK and American release, and it missed an opportunity to have these two notable actors fight a duel on the beach! Instead, Gordon fights the eye-patched Captain Tortuga who prefers not to fight fair, throwing sand in his adversary’s eyes, and engaging in other disreputable acts–perhaps because judging distance is difficult when fencing with eye (true, in fact). Gordon fights him again at the finale.

The backdrop of the duel is Howard Pyle-inspired, but lacks the sense of romantic adventure. Andrea and Franco Fantasia (see The Queen of Pirates above) are credited as fencing masters. The duel is largely Hollywood hack-and-slash, with large movements, cuts and slashes especially, quite untypical of rapier play, although there are a couple of tighter movements. The swords are cup-hilts, as usual and similarly anachronistic, assuming these aren’t Spanish pirates, which they might be, their names notwithstanding. Montalbán makes a fair attempt at a Flynn-like smirking composure, but is no fencer, often making the bent-arm stabs or pokes common to those who’ve never been taught to fence.

The movie is trope-filled, as the genre seems to require. Gordon is out to stop Romero from trading slaves, something no Caribbean pirates ever did or would have, unless to steal the slaves to sell themselves. In fact, the film opens with the duel on the beach. Captain Tortuga, it turns out, has been slave trading, something in reality pirates did quite regularly, capturing them at sea and on shore and selling them afterward.

The movie was filmed on the shores of Tuscany, probably in the same locations Queen of the Pirates was. The films were both directed by Mario Costa.

The Son of Captain Blood, 1962

Sean Flynn on the right in a classical en garde in a sword-fighting scene early in the film. It’s not truly a duel, nor on the beach although it is on the water. Rather, it’s a bit of a semi-comical sword brawl on the sandy shore of, ostensibly, Kingston, Jamaica. The film was an Italian-Spanish-US production featuring the son of Errol Flynn playing the son of Captain Peter Blood. Like his father, the younger Flynn looked the part of a swordsman even if his actual ability was far more theatrical than practical. A later swordfight in the film has been described by a friend of mine, himself an accomplished swordsman and swordplay teacher and choreographer, as probably the worst display of film sword combat ever filmed. I’ve been unable to discover who the film’s fight arranger was. Sean Flynn went to Vietnam in 1968 as a war correspondent. He, along with correspondent Dana Stone, were captured in Cambodia in 1970 and were never heard from again. They are generally believed to have been murdered either by the Viet Cong or the Khmer Rouge.

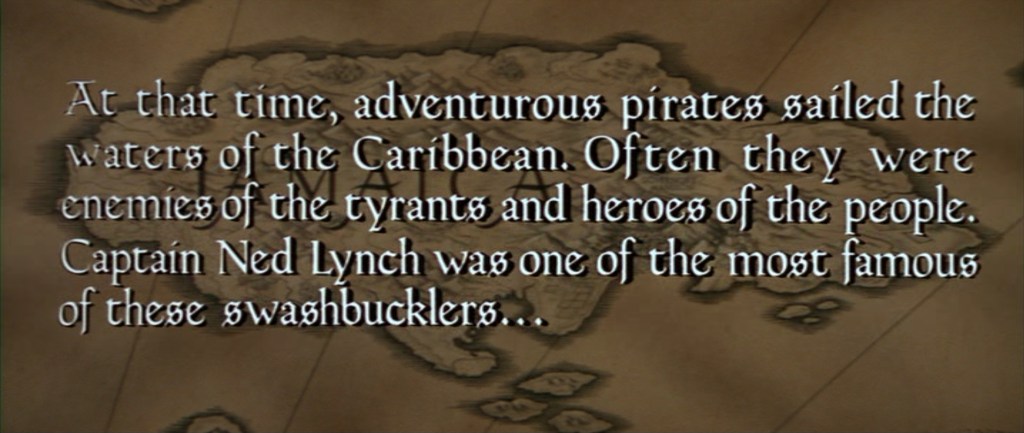

Swashbuckler, 1976

Starring Robert Shaw as Captain Ned Lynch, more or less reprising his former role as Dan Tempest in the television series The Buccaneers, and Genevieve Bujold as gentlewoman Jane Barnet, the film’s duel on the beach is as much or more titillation than plot development. One need only watch it or view the images below to recognize this immediately. Arguably, it does put the duelists’ personalities on display, but this we already have from other scenes. Still, who doesn’t enjoy watching swordplay on a tropical beach? And it is an important trope for the genre! The Swashbuckler duel was filmed on a beach near Puerta Vallarta, Mexico, to represent one somewhere on Jamaica.

The film indulges in numerous pirate tropes caricatures, including the myth of siding with a rebellious populace against an unjust government, and is filled with as many anachronisms as a Disney pirate film, ranging from “pirate boots” to the Blarney Cock (the replica Golden Hinde I once visited in San Diego in the 80s and one of my daughters in London a couple of years ago), a tall ship almost a century out of place–but at least it was a real ship and not a studio set! Even so, the film does (as my friend Antón Viejo Alonso reminded me) showcase Black actors–James Earl Jones as Nick Debrett and Jeffrey Holder as Cudjo–in prominent positions, including the role of Jones as what is essentially the ship’s quartermaster, or second-in-command, aboard pirate ships of the era. No other pirate films have done this so well, not even Black Sails. (The latter series did, however, do an admirable job showcasing African slaves in rebellion and allied with pirates, even if the latter is a myth. Full disclosure: I was the historical consultant for the show.)

Accepting the film for what it is–a 1970s update on The Black Pirate and The Crimson Pirate (in the UK it was released as The Scarlet Buccaneer) and a bit of an improvement on the old B-movies of the 1950s–it’s entirely enjoyable, or mostly so. All three leading actors–Shaw, Bujold, and Jones–take their roles seriously in spite of the occasional campyness and strange diversions (seriously, bath torture fetishism?) of the script.

The duel is fought with historically inaccurate swords as is common in Hollywood: Ned Lynch is armed with a cup-hilt rapier (with the classic Hollywood-issue modern epee blade instead of rapier blade), which commonly was used only by Iberians and some Italians at the time (1718) and almost out of style, and Jane Barnet with, for whatever imponderable, silly reason, a late 19th to early 20th century Radaelli fencing saber. The swordplay was choreographed with input from the film’s fencing consultant Tom Greene, a fencing student of Ralph Faulkner and a Hollywood writer and producer.

There are two other notable, if inauthentic, fencing scenes. In the first, the evil governor (played by Peter Boyle) and preening fetishist fences and defeats three Black fencing masters, killing one of them after he wounds the governor. If these Black fencers were of the standard of some of those on Barbados, I doubt the governor would have survived the encounters.

As Richard Ligon wrote in the 17th century, “I have seen some of these Portugal Negroes, at Collonel James Draxes, play at Rapier and Dagger very skilfully, with their Stookados, their Imbrocados, and their Passes: And at single Rapier too, after the manner of Charanza, with such comeliness…they were skilful too, which I perceived by their binding with their points, and nimble and subtle avoidings with their bodies. For, in this Science, I had been so well vers’d in my youth, as I was now able to be a competent judge.”

The final fencing scene is of the obligatory duel between Shaw and the governor.

Although as Hollywood goes the fencing in the duel isn’t entirely awful (it’s of the common standard, in other words, with lots of moulinets and the tierce-seconde, tierce-seconde action that’s simple to do and looks good on screen), and although there is little realism, Shaw does an excellent job giving a patronizing, chauvinistic air, and Bujold in return the rage at being outclassed and patronized. Both give spirited performances sword-in-hand. In fact, their relationship as revealed during their swordplay is more believable than during their romantic encounters although doubtless some readers will point out that adversarial engagements often stimulate romance. Or sometimes just lust.

The expanded original motion picture soundtrack (Quartet Records, 2 CDs, 2020), composed and conducted by John Addison, includes the duel track, “Fencing Lesson” (a mere 1:28 long).

Muppet Treasure Island 1996

Kermit showed off his best Hollywood swordplay, aerial antics included, engaged against Captain Flint as played by Tim Curry. If not strictly a duel, rather a rencontre on the beach during an attack on pirates, the swordplay is an enjoyable homage to film swashbucklers.

Pirates! 1986

By no means is the depicted duel a conventional one. Rather, it is deadly game (in this comedy) forced upon Spanish prisoners by their pirate captors, Captain Thomas Bartholomew Red, played by Walter Matthau, in particular. Two Spanish officers are forced to fight to the death on the shoulders of two other Spaniards, one of them a priest: “Dead Man’s Nag” is the name of the game according to Captain Red. The victor will be spared.

The scene is almost certainly inspired by an illustration in The Pirates Own Book by Charles Elms (1837) in which pirates ride on the shoulders of priests as a means of abusing them. The book panders to pirate tropes: its accuracy, however, leaves much to be desired. The swordplay in the “mounted” duel is actually not bad, even if as much cutting as thrusting. The fencing master is uncredited.

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, 2007

I hesitate to include this film because the scene is not a duel but a comical affray with swords on the beach, and soon gets even sillier. I won’t even mention but in passing the duel on the waterwheel scene. Yes, the scene is amusingly choreographed, and yes, it’s a fantasy film with pirates in it, not a pirate movie per se. Even so, the swordplay, such as there is, is the least memorable imagery of the entire scene. In fact, the comic reactions of Elizabeth Swann (played as everyone knows by Keira Knightley) are the most entertaining aspect of this romp with swords and treasure chest. Looking at the film credits, I’m unsure who choreographed the swordplay. As far as I know, the scene was filmed on St. Vincent in the Caribbean. I’ll say no more but to censure the screenwriter and director for not letting Miss Swann in her pirate garb get in on the action. It would have been quite something to have watched her swordfight-and-swashbuckle successfully against all three with her refined panache. Her swordplay on the beach is unfortunately limited to cutlass-play against several of living-dead crewmen of the Flying Dutchman.

Final Remarks…

I skipped a few films that qualify, or might. The Princess Bride’s duel above the beach probably deserves its own post. I’m unsure whether the duel in the treasure caves in the first Pirates of the Caribbean qualifies as a duel on the beach, or whether the fantasy elements disqualify it. There is a Russian version of Captain Blood, but the quality of available video is terrible and, if I recall correctly, the duel on the beach looks rather bland. I’ve also skipped a number of generic pirate sword battles on the beach. Well, with one mystery exception below of an affray or beach brawl, not a duel. 🙂

Next up, this series at least, a post devoted entirely and in depth to the famous duel in Captain Blood starring Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone!

*You can find portraits painted by Elias Katsaros on his Facebook page.

Copyright Benerson Little 2021-2025. First posted 24 August 2021. Last updated Juneteenth, 2025.

Reblogged this on Treasure Light Press.

LikeLike

Fine!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] post follows part one (the duel on the beach in fiction) and precedes part three (in […]

LikeLike

[…] Rafael Sabatini in The Black Swan, in particular the origin of the hero’s singular technique. Part three reviews the duel on the beach in film, part four (currently being written) takes a close look at […]

LikeLike

[…] on the Beach” posts is recommended but not required: In Fiction, in The Black Swan, and In Film. Some of the in-depth historical details below have been drawn from the annotations Treasure Light […]

LikeLike

As to the Russian version of Captain Blood:

(The duel scene starts at 16:00).

Could be childhood nostalgia for the Russian version, could be the utter lack of nostalgia for the “golden age” Hollywood version, but I enjoyed this duel a lot more. With all respect to the Olympic medalists flynning with Errol.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d like to find a quality print on DVD — I’ll check for a French release. 🙂 I’ve written a post on the Flynn-Rathbone duel here: https://benersonlittle.com/2022/03/29/the-duel-on-the-beach-part-iv-flynn-versus-rathbone-in-captain-blood/ Thanks for posting!

LikeLike

I’ll also suggest that the “Olympic” fencing of Fred Cavens and his assistant, Ralph Faulkner, was not too far removed from that of the dueling epee and saber of the era. Cavens had even reportedly fought duels, almost certainly with the epee de combat. My first fencing master, who was from the same era, had fought a saber duel. That said, it’s rare for the swordplay of any Hollywood film to display swordplay accurately re: period technique. 🙂

LikeLike

[…] you’ve read any or all of parts I though IV of this series (In Fiction, In Film, in Rafael Sabatini’s novel The Black Swan, and of the duel between Flynn and Rathbone in […]

LikeLike

[…] On the other hand, as I’ve pointed out in my post on Buccaneer Cutlasses, even a dull cutlass can split skin, break bones, and put eyes out, and any error in choreography could result in serious and possibly fatal injury. Thus the typical timing of the combats to musical accompaniment with a regular beat. No irregular rhythms here even though they’re ideally suited to real combat. It bears repeating: stage combat is not simply an imitation of real combat without real hits. (For further information on stage/film sword combat, see The Duel on the Beach in Captain Blood and The Duel on the Beach in Film.) […]

LikeLike